The Story of Greece by Mary MacGregor

MacGregor, Mary. The Story of Greece. London, T. C. and E. C. JACK, Ltd., 1914. Illustrated by Walter Crane.

CHAPTER I

WONDERLAND

The story of Greece began long, long ago in a strange wonderland of beauty. Woods and winds, fields and rivers, each had a pathway which led upward and onward into the beautiful land. Sometimes indeed no path was needed, for the rivers, woods, and lone hill-sides were themselves the wonderland of which I am going to tell.

In the woods and winds, in the trees and rivers, dwelt the gods and goddesses whom the people of long ago worshipped. It was their presence in the world that made it so great, so wide, so wonderful.

To the Hellenes, for that is the name by which the Greeks called themselves, there were eyes, living eyes in flowers, trees, and water. ‘So crowded full is the air with them,’ wrote one poet who lived in the far-off days, ‘that there is no room to put in the spike of an ear of corn without touching one.’

When the wind blew soft, the Hellenes listened to the whispering of a voice. When it blew rough, and snatched one of the children from their midst, they did not greatly grieve. The child had but gone to be the playmate of the gods.

The springs sparkled clear, for in them dwelt the Naiads or freshwater nymphs, with gifts as great as the river gods, who were ofttimes seen and heard amid the churning, tossing waters.

In the trees dwelt the Dryads, nymphs these of the forest,2 whom the Hellenes saw but seldom. Shy nymphs were the Dryads, born each one at the birth of a tree, in which she dwelt, fading away when the tree was felled, or when it withered and died.

Their revels were held in some wooded mountain, far from the haunts of men. Were a human footfall heard, the frolics ceased on the instant, while each Dryad sped swift for shelter to the tree of her birth.

So the gods wandered through the land, filling the earth with their presence. Yet there was one lofty mountain in central Greece, named Mount Olympus, which the Hellenes believed was the peculiar home of the gods. It was to this great mount that the actual roads on which the Hellenes walked each day seemed ever to lead.

On the sides of the mountain, green trees and dark pines clustered close. The summit reached high up, beyond the clouds, so used the ancient people to tell. Here, where no human foot had ever climbed, up beyond the twinkling stars, was the abode of the gods.

What the Hellenes never saw with their eyes, they saw quite clear with their imagination. Within the clouds, where the gods dwelt, they gazed in this strange way, upon marble halls, glistening with gold and silver, upon thrones too, great white thrones, finer far than those on which an earthly king might sit. The walls gleamed with rainbow tints, and beauty as of dawns and sunsets was painted over the vast arches of Olympus.

3

CHAPTER II

THE GREAT GOD PAN

The supreme god of the Hellenes was Zeus. He dwelt in the sky, yet on earth, too, he had a sanctuary amid the oak-woods of Dodona.

When the oak-leaves stirred, his voice was heard, mysterious as the voice of the mightiest of all the gods.

In days long after these, Phidias, a great Greek sculptor, made an image of Zeus. The form and the face of the god he moulded into wondrous beauty, so that men gazing saw sunshine on the brow, and in the eyes gladness and warmth as of summer skies.

Even so, if you watch, you may catch on the faces of those whose home is on the hill-side, or by the sea, a glimpse of the beauty and the wonder amid which they dwell.

It was only in very early times that the chief sanctuary of Zeus was at Dodona. Before they had dwelt long in Hellas, the Hellenes built a great temple in the plain of Olympia to their supreme god and named it the Olympian temple.

Here a gold and ivory statue of the god was placed, and to the quiet courts of the temple came the people, singing hymns and marching in joyous procession.

Zeus had stolen his great power from his father Kronus, with the help of his brothers and sisters. To reward them for their aid the god gave to them provinces over which they ruled in his name. Hera, Zeus chose as queen to reign with him. To Poseidon was given the sea, and a palace beneath the waves of the ocean, adorned with seaweed and with shells.

4

Pluto was made the guardian of Hades, that dark and gloomy kingdom of the dead, beneath the earth, while Demeter was goddess of the earth, and her gifts were flowers, fruits, and bounteous harvests.

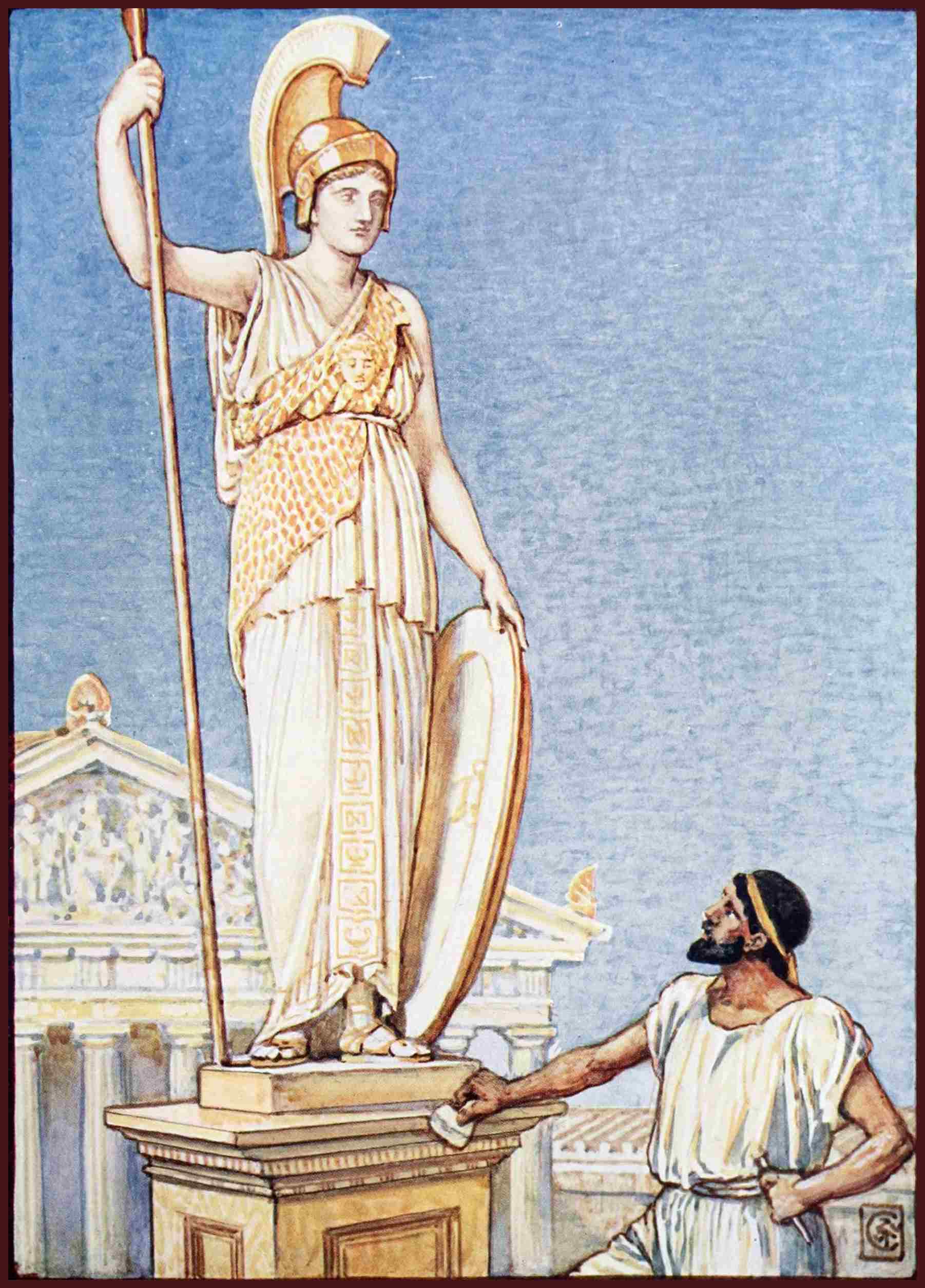

Athene was the goddess of war and wisdom, yet often she was to be seen weaving or embroidering, while by her table sat her favourite bird, an owl.

Hermes was known as the fleet-footed, for on his feet he wore winged sandals to speed him swift on the errands of the gods.

Apollo, the Sun-god, was the youngest of all the Olympian deities. He dwelt at Parnassus on the eastern coast of Greece, and his sanctuary was at Delphi.

The fairest of the goddesses was Aphrodite, Queen of Love. Her little son was named Eros, and he never grew up. Always he was a little rosy, dimpled child, carrying in his hands a bow and arrows.

Many more gods and goddesses were there in the wonder days of long ago, but of only one more may I stay to tell you now.

The great god Pan, protector of the shepherds and their flocks, was half man, half goat. Every one loved this strange god, who yet ofttimes startled mortals by his wild and wilful ways. When to-day a sudden, needless fear overtakes a crowd, and we say a panic has fallen upon it, we are using a word which we learned from the name of this old pagan god.

Down by the streams the great god Pan was sometimes seen to wander—

5

and then sitting down he ‘hacked and hewed, as a great god can,’ at the slender reed. He made it hollow, and notched out holes, and lo! there was a flute ready for his use.

Sweet, piercing sweet was the music of Pan’s pipe as the god placed his mouth upon the holes.

On the hill-sides and in the fields of Hellas, the shepherds heard the music of their god and were merry, knowing that he was on his way to frolic and to dance among them.

Pan lived for many, many a long year; but there is a story which tells how on the first glad Christmas eve, when Jesus was born in Bethlehem, a traveller, as he passed Tarentum, the chief Greek city in Italy, heard a voice crying, ‘The great god Pan is dead.’

And when this same Jesus had grown to be a Man, and ‘hung for love’s sake on a Cross,’ one of our own women poets sings that all the old gods of Greece

And the reason that the old gods fell was that the strange Man upon the Cross was mightier than they. But in the days of ancient Greece the gods were alive and strong; of that the Hellenes were very sure.

6

CHAPTER III

THE SIX POMEGRANATE SEEDS

Demeter, the goddess of the earth, was often to be seen in the fields in springtime. As the Greek peasants sowed their seed they caught glimpses of her long yellow hair while she moved now here, now there, among them. It almost seemed to these simple folk as though already the bare fields were golden with the glory of harvest, so bright shone the yellow hair of the goddess. Then they smiled hopefully one to the other, knowing well that Demeter would give them a bounteous reaping-time.

In the autumn she was in the fields again, the peasants even dreamed that they saw her stoop to bind the sheaves. Certainly she had been known to visit their barns when the harvest was safely garnered. And stranger still, it was whispered among the womenfolk that the great Earth-Mother had entered their homes, had stood close beside them as they baked bread to feed their hungry households.

It was in the beautiful island of Sicily, which lies in the Mediterranean Sea, that the goddess had her home. Here she dwelt with her daughter Persephone, whom she loved more dearly than words can tell.

Persephone was young and fair, so fair that she seemed as one of the spring flowers that leaped into life when her mother touched the earth with her gracious hands.

Early as the dawn the maiden was in the fields with Demeter, to gather violets while the dew still lay upon them, to dance and sing with her playmates. At other times she7 would move gravely by the side of her mother to help her in her quiet labours.

All this time, Pluto, King of Hades, was living in his gloomy kingdom underground, longing for some fair maiden to share his throne. But there was not one who was willing to leave the glad light of the sun, no, not though Pluto offered her the most brilliant gems in his kingdom.

One day the dark king came up out of the shadows, riding in his chariot of gold, drawn by immortal horses. Swifter was their pace than that of any mortal steeds.

Persephone was in a meadow with her playfellows when the king drew near. The maiden stood knee-deep amid the meadow-grass, and, stooping, plucked the fragrant sweet flowers all around her—hyacinth, lilies, roses, and pale violets.

Pluto saw the group of happy maidens, beautiful each one as a day in spring, but it was Persephone who charmed him more than any other.

‘She shall be my queen and share my throne,’ muttered the gloomy king to himself. Then, for he knew that to woo the maiden would be vain, Pluto seized Persephone in his arms, and bore her weeping to his chariot.

Swift as an arrow the immortal steeds sped from the meadow, where Persephone’s playmates were left terror-stricken and dismayed.

On and on flew the chariot. Pluto was in haste to reach Hades ere Demeter should miss her daughter.

A river lay across his path, but of this the king recked naught, for his steeds would bear him across without so much as lessening their speed.

But as the chariot drew near, the waters began to rise as though driven by a tempest. Soon they were lashed to such fury that Pluto saw that it was vain to hope to cross to the other side. So he seized his sceptre, and in a passion he struck three times upon the ground. At once a great chasm opened in the earth, and down into the darkness8 plunged the horses. A moment more and Pluto was in his own kingdom, Persephone by his side.

When the king seized the maiden in the meadow, and bore her to his chariot, she had cried aloud to Zeus, her father, to save her. But Zeus had made no sign, nor had any heard save Hecate, a mysterious goddess, whose face was half hidden by a veil.

None other heard, yet her piteous cry echoed through the hills and woods, until at length the faint echo reached the ear of Demeter.

A great pain plucked at the heart of the mother as she heard, and throwing the blue hood from off her shoulders, and loosening her long yellow hair, Demeter set forth, swift as a bird, to seek for Persephone until she found her.

To her own home first she hastened, for there, she thought, she might find some trace of the child she loved so well. But the rooms were desolate as ‘an empty bird’s nest or an empty fold.’

The mother’s eyes searched eagerly in every corner, but nothing met her gaze save the embroidery Persephone had been working, ‘a gift against the return of her mother, with labour all to be in vain.’ It lay as she had flung it down in careless mood, and over it crept a spider, spinning his delicate web across the maiden’s unfinished work.

For nine days Demeter wandered up and down the earth, carrying blazing torches in her hands. Her sorrow was so great that she would neither eat nor drink, no, not even ambrosia, or a cup of sweet nectar, which are the meat and drink of the gods. Nor would she wash her face. On the tenth day Hecate came towards her, but she had only heard the voice of the maiden, and could not tell Demeter who had carried her away.

Onward sped the unhappy mother, sick at heart for hope unfulfilled, onward until she reached the sun. Here she learned that it was Pluto who had stolen her daughter, and carried her away to his gloomy kingdom.

9

Then in her despair Demeter left all her duties undone, and a terrible famine came upon the earth. ‘The dry seed remained hidden in the soil; in vain the oxen drew the ploughshare through the furrows.’

As the days passed the misery of the people grew greater and greater, until faint and starving they came to Demeter, and besought her once again to bless the earth.

But sorrow had made the heart of the goddess hard, and she listened unmoved to the entreaties of the hungry folk, saying only that until her daughter was found she could not care for their griefs.

Long, weary days Demeter journeyed over land and sea to seek for Persephone, but at length she came back to Sicily.

One day as she walked along the bank of a river, the water gurgled gladly, and a little wave carried a girdle almost to her feet.

Demeter stooped to pick it up, and lo! it was the girdle that Persephone had worn on the day that she had been carried away. The maiden had flung it into the river as the chariot had plunged into the abyss, hoping that it might reach her mother. The girdle could not help Demeter to recover her daughter, yet how glad she was to have it, how safe she treasured it!

At length, broken-hearted indeed, Demeter went to Zeus to beg him to give her back her daughter. ‘If she returns the people shall again have food and plenteous harvests,’ she cried. And the god, touched with the grief of the mother and the sore distress of the people, promised that Persephone should come back to earth, if she had eaten no food while she had lived in the gloomy kingdom of Hades.

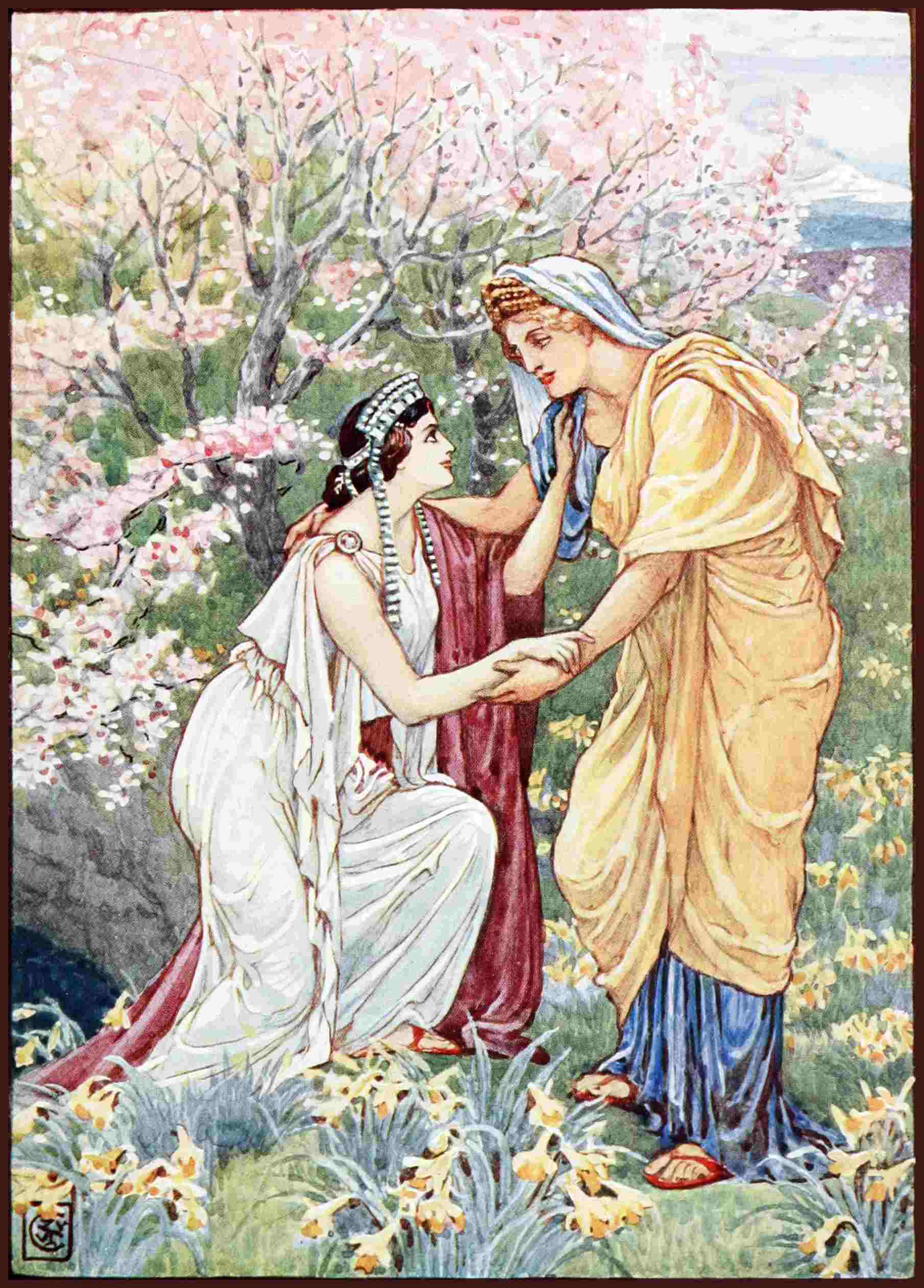

No words can tell the joy with which Demeter hastened to Hades. Here she found her daughter with no smile upon her sweet face, but only tears of desire for her mother and the dear light of the sun. But alas! that very day Persephone had eaten six pomegranate seeds. For every10 seed that she had eaten she was doomed to spend a month each year with Pluto. But for the other six months, year after year, mother and daughter would dwell together, and as they clung to one another they were joyous and content.

So for six glad months each year Demeter rejoiced, for her daughter was by her side, and ever it was spring and summer while Persephone dwelt on earth. But when the time came for her to return to Hades, Demeter grew ever cold and sad, and the earth too became weary and grey. It was autumn and winter in the world until Persephone returned once more.

11

CHAPTER IV

THE BIRTH OF ATHENE

One day Zeus was ill. To us it is strange to think of the gods as suffering the same pains as mortals suffer, but to the Hellenes it seemed quite natural.

Zeus was ill. His head ached so severely that he bade all the gods assemble in Olympus to find a cure for his pain. But not one of them, not even Apollo, who was god of medicine as well as Sun-god, could ease the suffering deity.

After a time Zeus grew impatient with the cruel pain, and resolved at all costs to end it. So he sent for his strong son Hephaestus, and bade him take an axe and cleave open his head.

Hephaestus did not hesitate to obey, and no sooner had the blow descended than from his father’s head sprang forth Athene, the goddess of war and wisdom. She was clad in armour of pure gold, and held in her hand a spear, poised as though for battle. From her lips rang a triumphant war-song.

The assembled gods gazed in wonder, not unmixed with fear at the warrior goddess, who had so suddenly appeared in their midst. But she herself stood unmoved before them, while a great earthquake shook the land and proclaimed to the dwellers in Hellas the birth of a new god.

Athene was a womanly goddess as well as a warlike one. She presided over all kinds of needlework, and herself loved to weave beautiful tapestries.

Soon after the birth of the goddess a man named Cecrops came to a province in Greece, which was afterwards known12 as Attica. Here he began to build a city, which grew so beautiful beneath his hands that the gods in Olympus marvelled. When it was finished, each of the gods wished to choose a name for the city Cecrops had built.

As only one name could be used, the gods met in a great council to determine what was to be done. Soon, one by one, each gave up his wish to name the city, save only Athene and Poseidon.

Then Zeus decreed that Athene and Poseidon should create an object which would be of use to mortals. To name the city and to care for it should be the prize of the one who produced the more useful gift.

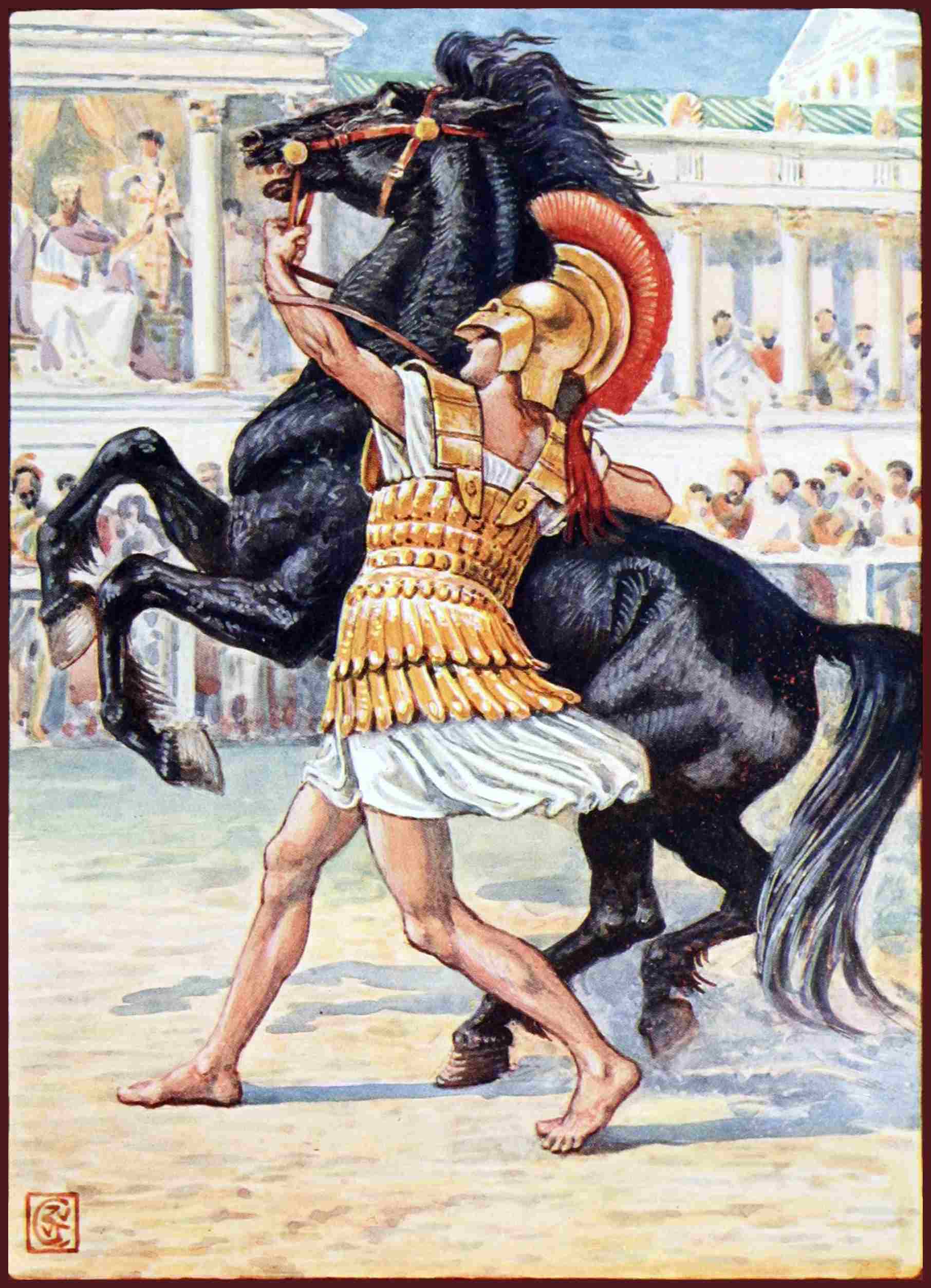

Poseidon at once seized his three-pronged fork or trident, which was the sign that he was ruler of the sea. As he struck the ground with it lo! a noble horse sprang forth, the first horse that the gods had seen.

As Poseidon told the gods in how many ways the beautiful animal could be of use to mortals, they thought that Athene would not be able to produce anything that could help men more.

When she quietly bade the council to look at an olive-tree, the gods laughed her to scorn. But they soon ceased to laugh. For Athene told them how the wood, the fruit, the leaves, all were of use, and not only so, but that the olive-tree was the symbol of peace, while the horse was the symbol of war. And war did ever more harm than good to mortals.

So the gods decided that it was Athene who had won the right to name the city, and she gave to it her own name of Athene, and the citizens ever after worshipped her as their own peculiar goddess.

Of this city, which we know as Athens, you will hear much in this story.

13

CHAPTER V

THE TWO WEAVERS

Athene could not only wield the sword, she could also ply the needle.

In these olden days there lived in Greece a Lydian maid who could weave with wondrous skill. So beautiful were the tapestries she wrought that her fame spread far and wide. Lords and ladies both came from distant towns to see the maiden’s skilful hands at work.

Arachne, for that was the maiden’s name, lived in a cottage with her parents. They were poor folk, and had often found it hard to earn their daily bread. But now that their daughter was famous for her embroidery their troubles were at an end. For not only lords and ladies, but merchants, too, were glad to pay well to secure the young maid’s exquisite designs.

And so all would have been well with Arachne and her parents had not the foolish girl become vain of her work. Soon her companions began to weary of her, for of nothing could she talk save of her own deft fingers, of her own beautiful embroideries.

Those who loved Arachne grew sad as they listened to her proud words, and warned her that ‘pride ever goes before a fall.’

But Arachne only tossed her pretty head as she listened to the wisdom of older folk. Nor did she cease to boast, even saying that she could do more wonderful work than the goddess Athene.

Not once, but many times did Arachne say that she14 wished she might test her skill against that of the goddess. And should a prize be offered, proudly she declared that it was she who would win it.

From Olympus Athene heard the vain words of the maid. So displeased was she with her boldness that she determined to go to see Arachne, and if she did not repent to punish her.

She changed herself into an old white-haired dame, and came to earth. Leaning upon a staff she knocked at the door of the cottage where Arachne lived, and was bidden to enter.

Arachne was sitting in the midst of those who had come to see and to praise her work. Soon she began to talk, as she was quick to do, of her skill, and of how she believed that her work surpassed in beauty any that Athene could produce.

The old woman pushed her way through the group that surrounded the maid, and laying her hand upon the shoulder of Arachne she spoke kindly to her.

‘Be more modest, my child,’ she said, ‘lest the anger of the gods descend upon you, lest Athene take you at your word, and bid you to the contest you desire.’

Impatiently Arachne shook off the stranger’s hand, and answered, ‘Who are you who dare speak to me? I would Athene might hear my words now, and come to test her skill against mine. She would soon see that she had a rival in Arachne.’

Athene frowned at the insolence of the maiden. Then the little company were startled to see the old woman suddenly change into the glorious form of the goddess Athene. As they gazed they were afraid and fell at her feet.

But Arachne did not worship the goddess. Foolish Arachne looked boldly in her face, and asked if she had come to accept her challenge.

Athene’s only answer was to sit down before an empty15 loom. Soon each, in silence, had begun to weave a wondrous tapestry.

Swift and more swift moved the fingers of the weavers, while the group of strangers, gathered now near to the door, watched the webs as they grew and grew apace.

Into her tapestry Athene was weaving the story of her contest with Poseidon for the city of Cecrops. The olive-tree, the horse, the gods in the council, all seemed to live as they appeared on the web of the goddess.

The tapestry woven by Arachne was also beauteous as her work was wont to be. In it you saw the sea, with waves breaking over a great bull, to whose horns clung a girl named Europa. And Europa’s curls blew free in the wind.

At length Athene rose from the loom, her work complete. Arachne, too, laid down her spindle, and as she turned to look upon the tapestry of the goddess her courage suddenly failed.

A glance had been enough to show her that her skill was as nothing before the wonder and the beauty of Athene’s work.

Too late the maiden repented that she had defied the goddess. In her despair she seized a rope and tied it round her neck to hang herself.

But the goddess saw what Arachne meant to do, and at once she changed her into a spider, bidding her from henceforth never cease to spin.

And so when you see a spider weaving its beautiful embroidery on a dewy morning in the garden, or when you find a delicate web in your lumber-room, you will remember how Athene punished poor foolish Arachne in the days of old.

16

CHAPTER VI

THE PURPLE FLOWERS

Apollo, the youngest and most beautiful of all the gods, dearly loved a lad named Hyacinthus.

Ofttimes he would leave the other gods sipping nectar in Mount Olympus, ofttimes he would forsake the many beautiful temples in which he was worshipped on earth, that he might be free to wander through the woods with his little friend.

For Hyacinthus was only a merry little lad, who loved to roam over hill and dale, and when the fancy seized him to hunt in the woods.

Apollo was never happier than when he was with the boy. Sometimes he would go hunting with him, and then Hyacinthus was merrier than ever, for the world seemed more full of brightness when the Sun-god was by his side. Sometimes the friends would walk together over hill and dale, followed by the dogs Hyacinthus loved so well.

One day they had wandered far, and the little lad was tired, so he flung himself down in a grassy meadow to rest, Apollo by his side. But the Sun-god was soon eager for a game. He sprang to his feet, crying, ‘Hyacinthus, let us play at quoits before the shadows fall.’

Quoits were flat, heavy discs, and the game was won by the player who could fling the quoits the farthest through the air.

Hyacinthus was ever willing to do as Apollo wished, and the game was soon begun. After a throw of more than usual skill and strength the friends laughed gleefully.

O but it was good to be alive in such a happy world, thought Hyacinthus. And Apollo, as he looked at the17 merry face of the little lad, rejoiced that he was not sitting in the cold marble halls of Olympus, but was here on the glad green earth.

By and by while they still played, Zephyrus, the god of the south wind, came fleeting by. He saw the Sun-god and his little playmate full of laughter and of joy.

Then an ugly passion, named jealousy, awoke in the heart of the god, for he too loved the little hunter Hyacinthus, and would fain have been in Apollo’s place.

Zephyrus tarried a while to watch the friends. Once as Apollo flung his disc high into the air, the Wind-god sent a gust from the south which blew the quoit aside. He meant only to annoy Apollo, but Hyacinthus was standing by, so that the quoit struck him violently on the forehead.

The lad fell to the ground, and soon he was faint from loss of blood.

In vain Apollo tried to staunch the wound; nothing he could do was of any use. Little by little the boy’s strength ebbed away, and the Sun-god knew that the lad would never hunt or play again on earth. Hyacinthus was dead.

The grief of the god was terrible. His tears fell fast as he mourned for the playmate he had loved so well.

At length he dried his tears and took his lyre, and as he played he sang a last song to his friend. And all the woodland creatures were silent that they might listen to the love-song of the god.

When the song was ended, Apollo laid aside his lyre, and, stooping, touched with his hand the blood-drops of the lad. And lo! they were changed into a cluster of beautiful purple flowers, which have ever since been named hyacinths, after the little lad Hyacinthus.

Year by year as the spring sun shines, the wonderful purple of the hyacinth is seen. Then you, who know the story, think of the days of long ago, when the Sun-god lost his little friend and a cluster of purple flowers bloomed upon the spot where he lay.

18

CHAPTER VII

DANAE AND HER LITTLE SON

The stories I have told you are about the gods of ancient Greece; the story I am going to tell you now is about a Greek hero.

When you think of a hero, you think of a man who does brave, unselfish deeds. But to the Hellenes or Greeks a hero was one who was half god, half man—whose one parent was a god while the other was a mortal. So the god Zeus was the father of Perseus, the hero of whom I am going to tell, while his mother was a beautiful princess named Danae.

From morning to night, from night till morning, Acrisius, the father of Danae, was never happy. Yet he was a king.

A king and unhappy? Yes, this king was unhappy because he was afraid that some day, as an oracle had foretold, he would be slain by his grandson.

The ancient Greeks often sent to sacred groves or temples to ask their gods about the future, and the answer, which was given by a priestess, was called an oracle.

Now Acrisius, King of Argos, had no grandson, so it was strange that the oracle should make him afraid. He hoped that he never would have a grandson.

His one child, beautiful, gentle Danae he had loved well until he had heard the oracle. Now he determined to send her away from the palace, to hide her, where no prince would ever find her and try to win her for his bride.

So the king shut the princess into a tower, which was encased in brass and surrounded it with guards, so that no one, and least of all a prince, could by any chance catch a glimpse of his beautiful daughter.

Very sad was Danae, very lonely, too, when she was left in the brazen tower, and Zeus looking down from Olympus pitied her, and before long sent a little son to cheer her loneliness.

One day the guards saw the babe on his mother’s knee. Here was the grandson about whom the king had hoped that he would never be born.

In great alarm they hastened to the palace to tell the king the strange tidings. Acrisius was so frightened when he heard their story that he flew into a passion, and vowed that both Danae and Perseus, as her little son was named, should perish. So he ordered the guards to carry the mother and her babe to the seashore, and to send them adrift on the waters in an empty boat.

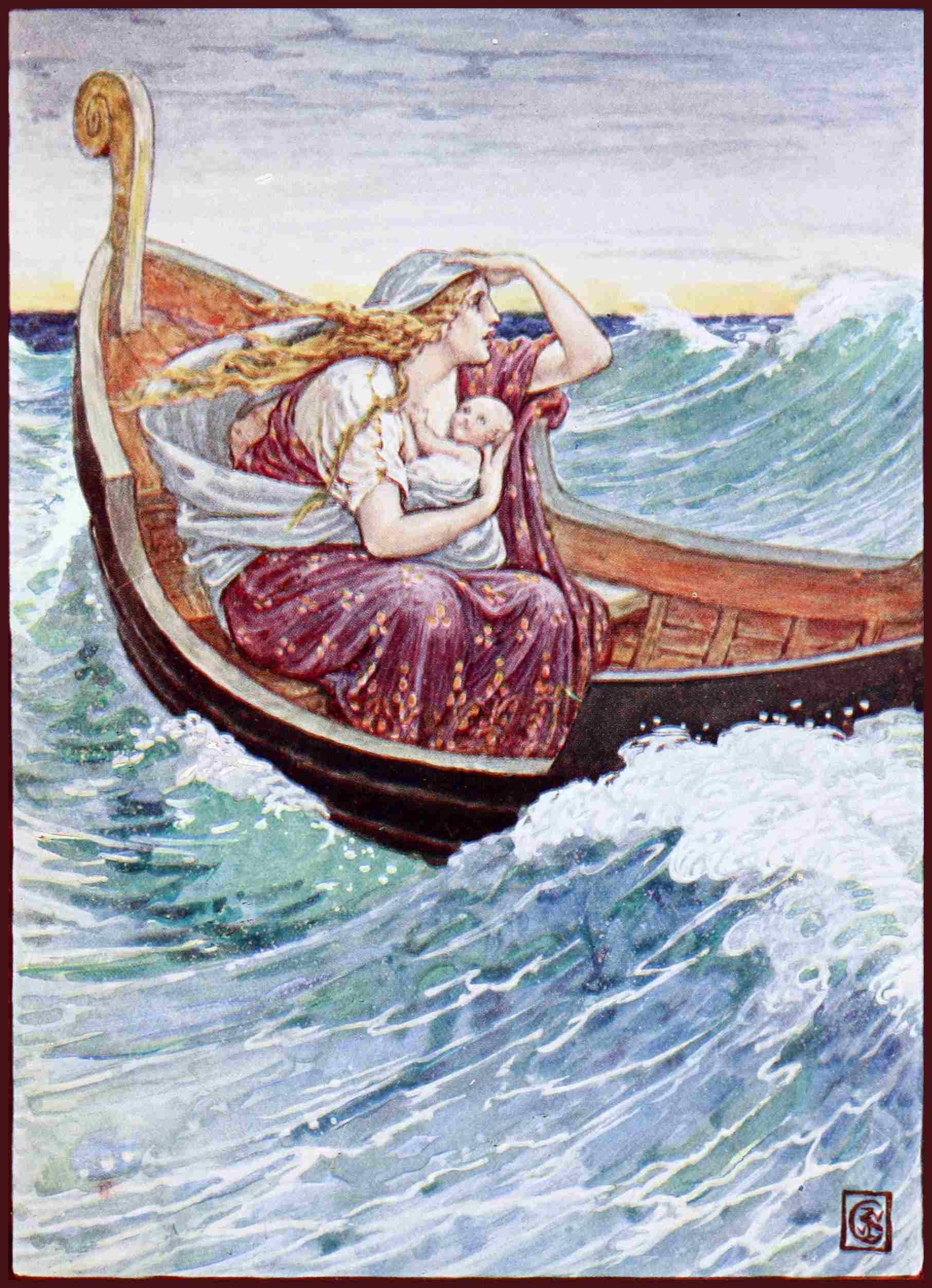

For two days and two nights the boat was tossed hither and thither by the winds and the waves, while Danae, in sore dismay but with a brave heart, clasped her golden-haired boy tight in her arms.

The child slept sound in the frail bark, while his mother cried to the gods to bring her and her treasure into a safe haven.

On the third day the answer to her prayers came, for before her Danae saw an island with a shore of yellow sand. And on the shore stood a fisherman with his net, looking out to sea. He soon caught sight of the boat, and as it drew near he cast his net over it, and gently pulled it to the shore.

It seemed to Danae almost too good to be true, to stand once again on dry land. She thought it was but a dream, from which she would awake to find herself once more tossing on the great wide sea.

But there stood Dictys, the fisherman, looking at her in wonder. Then Danae knew that she was indeed awake.20 She hastened to thank him for his help, and to ask him where she could find shelter for herself and her child.

Then the fisherman, who was the brother of Polydectes, king of the island on which Danae had landed, said that if she would go with him to his home he would treat her as a daughter. And Danae went gladly to live with Dictys.

So Perseus grew up in the island of Seriphus, playing on the sands when he was small, and when he had grown tall and strong going voyages to other islands with Dictys, or fishing with him nearer home. Zeus loved the lad and watched over him.

Fifteen years passed, and then the wife of Polydectes died, and the king wished to marry Danae, for he loved her and knew that she was a princess.

But Danae did not wish to wed Polydectes, and she refused to become his queen, for indeed she loved no one save her son Perseus.

Then the king was angry, and vowed that if Danae would not come to the palace as his queen, he would compel her to come as his slave.

And it was even so, as a slave, that Perseus found her, when he returned from a voyage with Dictys.

The anger of the lad was fierce. How dare any one treat his beautiful mother so cruelly! He would have slain the king had not Dictys restrained him.

Subduing his anger as well as he could, Perseus went boldly to the palace, and taking no heed of Polydectes, he brought his mother away and left her in the temple of Athene. There she would be safe, for no one, not even the king, would enter the sanctuary of the goddess.

‘Perseus must leave the island,’ said Polydectes when he was told of the lad’s bold deed. He thought that if her son were banished Danae would perchance be willing to become his queen.

But Polydectes was too crafty to issue a royal command bidding Perseus leave Seriphus. That, he knew, would 21make Danae hate him more than ever, so he thought of a better way to get rid of the lad. He arranged to give a great feast in the palace, and proclaimed that each guest should bring a gift to present to the king.

Among other youths, Perseus, too, was invited, but he was poor and had no gift to bring. And this was what the unkind king wished.

So when Perseus entered the palace empty-handed, Polydectes was quick to draw attention to the lad, laughing at him and taunting him that he had not done as the other guests and brought with him a gift. The courtiers followed the example of their king, and Perseus found himself attacked on every side.

The lad soon lost his temper, and looking with defiance at Polydectes, he cried, ‘I will bring you the head of Medusa as a gift, O King, when next I enter the palace!’

‘Brave words are these, Perseus,’ answered the king. ‘See that you turn them into deeds, or we shall think you but boast as does a coward.’

Then as Perseus turned and left the banqueting-hall the king laughed well pleased, for he had goaded the lad until he had fallen into the trap prepared for him. If Perseus went in search of the head of Medusa, he was not likely to be seen again in Seriphus, thought the king.

And Perseus, as he walked away toward the sea, was saying to himself, ‘Yes, I shall go in search of Medusa, nor shall I return unless I bring her head with me, a gift for the king.’

22

CHAPTER VIII

THE QUEST OF PERSEUS

Medusa and her two sisters were named the Gorgons. The sisters had always been plain and even terrible to see, but Medusa had once been fair to look upon.

When she was young and beautiful her home was in a northern land where the sun never shone, so she begged Athene to send her to the south where sunshine made the long days glad. But the goddess refused her request.

In her anger Medusa cried, ‘It is because I am so beautiful that you will not let me go. For if Medusa were to be seen who then would wish to look at Athene.’

Such proud and foolish words might not be suffered by the gods, and the maiden was sharply punished for her rash speech. Her beautiful curly hair was changed into serpents, living serpents that hissed and coiled around her head. Nor was this all, but whoever so much as glanced at her face was at once turned into stone.

Terrible indeed was Medusa, the Gorgon, whose head Perseus had vowed to bring as a gift to Polydectes. She had great wings like eagles and sharp claws instead of hands.

Now as Perseus wandered down to the shore after he had defied the king, his heart began to sink. How was he even to begin his task? He did not know where Medusa lived, nor did any one on the island.

In his perplexity he did as his mother had taught him to do; he prayed to Athene, and lo! even as he prayed the23 goddess was there by his side. With her was Hermes, the fleet-footed, wearing his winged sandals.

‘The gods will aid you, Perseus,’ said Athene, ‘if you will do as they bid you. But think not to find their service easy. For they who serve the gods must endure hardship, and live laborious lives. Will this content you?’

Perseus had no fears now that he knew the gods would help him, and with a brave and steadfast heart he answered, ‘I am content.’

Then Pluto sent to the lad his magic helmet, which made whoever wore it invisible. Hermes gave to him the winged sandals he wore, so that he might be able to fly over land and sea, while Athene entrusted to him her shield, the dread Ægis, burnished bright as the sun. The shield was made from the hide of a goat, but the Hellenes thought of it as the great storm-cloud in which Zeus hid himself when he was angry. For it was the shield of her father Zeus that Athene used.

Upon Medusa herself Perseus would not be able to cast a glance lest he be turned to stone, but looking at the shield he would see her image as in a mirror.

The lad was now armed for his quest, but not yet did he know whither it would lead.

But Athene could direct him. She said that the abode of the Gorgons was known to none save three sisters called the Grææ. These sisters had been born with grey hair, and had only one eye and one tooth between them, which they used in turn. Their home was in the north, in a land of perpetual darkness, and it was there that Perseus must go to learn the dwelling-place of the Gorgons. So at length the lad was ready to set out on his great adventure.

On and on, sped by his winged sandals he flew, past many a fair town, until he left Greece far behind. On and on until he reached the dark and dreary land where the Grææ dwelt. He could see them now, the three grey sisters, as they sat in the gloom just outside their cave.

24

As Perseus drew near, unseen by them, because of his magic helmet, the sisters were passing their one eye from hand to hand, so that at that moment all three were blind.

Perseus saw his chance, and stretching out his hand seized the eye. They, each thinking the other had it, began to quarrel. But Perseus cried, ‘I hold the eye in my hand. Tell me where I may find Medusa and you shall have it back.’

The sisters were startled by a voice when they had neither seen nor heard any one approach; they were more startled by what the voice said.

Very unwilling were they to tell their secret, yet what could they do if the stranger refused to give back their one eye? Already he was growing impatient, and threatening to throw it into the sea. So lest he should really fling it away they were forced to tell him where he would find the Gorgon. Then Perseus, placing the eye in one of the eager, outstretched hands, sped swiftly on his journey.

As he reached the land of which the Grææ had told him, he heard the restless beating of the Gorgon’s wings, and he knew that his quest was well-nigh over.

Onward still he flew, and then raising his burnished shield he looked into it, and lo! he saw the images of the Gorgons. They lay, all three, fast asleep on the shore.

Unsheathing his sword, Perseus held it high, and then, keeping his gaze fixed upon the shield, he flew down and swiftly cut off Medusa’s head and thrust it into a magic bag which he carried slung over his shoulder.

Now as Perseus seized the terrible head, the serpents coiled around the Gorgon’s brow roused themselves, and began to hiss so fiercely that the two sisters awoke and knew that evil had befallen Medusa.

They could not see Perseus, for he wore his magic helmet, but they heard him, and in an instant they were following fast, eager to avenge the death of their sister.

For a moment the brave heart of the hero failed.

25

Was he doomed to perish now that his task was accomplished?

He cried aloud to Athene, for he heard the Gorgons following ever closer on his path. Then more swiftly sped the winged sandals, and soon Perseus breathed freely once again, for he had left the dread sisters far behind.

26

CHAPTER IX

ANDROMEDA AND THE SEA-MONSTER

As Perseus journeyed over land and sea on his great quest, he often thought of the dear mother he had left in Seriphus. Now that his task was done he longed to fly over the blue waters of the Mediterranean to see her, to know that she was safe from the cruel King Polydectes. But the gods had work for Perseus to do before he might return to his island home.

Again and again the lad struggled against wind and rain, trying ever to fly in the direction of Seriphus, but again and again he was beaten back.

Faint and weary he grew, tired too of striving, so that he thought he would die in the desert through which he was passing.

Then all at once it flashed across his mind that Hermes had told him that as long as he wore the winged sandals he could not lose his way. New courage stole into his heart as he remembered the words of the god, and soon he found that he was being carried with the wind toward some high mountains. Among them he caught sight of a Titan or giant named Atlas, who had once tried to dethrone Zeus, and who for his daring had been doomed to stand,

The face of Atlas was pale with the mighty burden he bore, and which he longed to lay down. As he caught sight of Perseus he thought that perhaps the stranger would be able to help him, for he knew what Perseus carried in his magic27 bag. So as he drew near Atlas cried to him, ‘Hasten, Perseus, and let me look upon the Gorgon’s face, that I may no longer feel this great weight upon my shoulders.’

Then in pity Perseus drew from the magic bag the head of Medusa, and held it up before the eyes of Atlas. In a moment the giant was changed into stone, or rather into a great rugged mountain, which ever since that day has been known as the Atlas Mountain.

The winged sandals then bore Perseus on until he reached a dark and desolate land. So desolate it was that it seemed to him that the gods had forsaken it, or that it had been blighted by the sins of mortals. In this island lived Queen Cassiopeia with her daughter Andromeda.

Cassiopeia was beautiful, but instead of thanking the gods for their gift of beauty, she used to boast of it, saying that she was fairer than the nymphs of the sea.

So angry were the nymphs when they heard this, that they sent a terrible monster to the island, which laid it waste, and made it dark and desolate as Perseus had seen.

The island folk sent to one of their temples to ask what they could do to free their island from the presence of the sea-serpent.

‘This monster has been sent to punish Cassiopeia for her vain boast,’ was the answer. ‘Bid her sacrifice her daughter Andromeda to the sea-serpent, then will the nymphs remove the curse from your homes.’

Andromeda was fair and good, and the people loved her well, so that they were greatly grieved at the oracle. Yet if they did not give up their princess their homes would be ruined, their children would perish before their eyes.

So while the queen shut herself up in her palace to weep, the people took the beautiful maiden down to the shore and chained her fast to a great rock. Then slowly, sorrowfully, they went away, leaving her a prey to the terrible monster.

As Perseus drew nearer to the sea he saw the maiden.28 The next moment he was gazing in horror at the sea-serpent, as with open, hungry jaws it approached its victim.

Quick as lightning Perseus drew his sword and swooped down toward the monster, at the same moment holding before him the head of Medusa.

As the eyes of the serpent fell upon that awful sight, it slipped backward, and before Perseus could use his sword, it was changed into a rock, a great black rock. And if you go to the shore of the Levant you may see it still, surrounded by the blue waters of the Mediterranean.

29

CHAPTER X

ACRISIUS IS KILLED BY PERSEUS

As soon as Perseus saw that the monster was harmless, he took off his magic helmet, and hastening to Andromeda he broke the chain that held her to the rock. Then bidding her fear no more he led her back to the palace, where the queen sat weeping for her lost daughter.

When the door of her room was opened Cassiopeia never stirred. Andromeda’s arms were around her, Andromeda’s kisses were on her cheek before she could believe that her daughter was in very truth alive. Then, indeed, the mother’s joy was boundless.

So fair, so good was the maiden that Perseus loved her, and thanked the gods who had led him to that desolate land. Before many weeks had passed the princess was wedded to the stranger who had saved her from the terrible sea-monster.

Twelve months later they left Cassiopeia, and sailed away to Seriphus, for Perseus longed to see his mother, and to bring to her his beautiful bride.

Seven long years had passed since Perseus set out on his quest, and Danae’s heart was glad when she saw her son once more.

As soon as their greetings were over, Perseus left Andromeda with his mother, and went to the palace, carrying with him the head of Medusa in the magic bag.

The king was feasting with his nobles when Perseus entered the banqueting-hall. Long, long ago he had ceased to think of Perseus, for he believed that he had perished on30 his wild adventure. Now he saw him, grown to be a man, entering the hall, and he grew pale with sudden fear.

Paying no heed to any, Perseus strode through the throng of merry courtiers until he stood before the throne on which sat Polydectes.

‘Behold the gift I promised you seven years ago, O King!’ cried Perseus, and as he spoke he drew forth the head of Medusa and held it up for the king to see.

Polydectes and his startled nobles stared in horror at the awful face of the Gorgon, and as they gazed the king and all his followers were changed into figures of stone.

Then Perseus turned and left the palace, and telling the island folk that Polydectes was dead, he bade them now place Dictys, the fisherman, upon the throne.

He then hastened to the temple of Athene, and with a glad heart gave back to the goddess the gifts which had served him so well—the helmet, the sandals, the shield.

As his own offering to Athene he gave the head of the Gorgon. She, well pleased, accepted it, and had it placed in the centre of her shield, so from that day the Ægis became more terrible than before, for the Gorgon’s head still turned to stone whoever looked upon it.

Danae had often talked to Perseus when he was a boy of Acrisius, her father, and of Argos, the city from which he had been banished when he was a babe. Perseus now resolved to sail to Argos with Danae and Andromeda. During these years Acrisius had been driven from his throne by an ambitious prince. He was in a miserable dungeon, thinking, it may be, of his unkindness to his daughter Danae, when she once again reached Argos.

Perseus soon drove away the usurper, and for his mother’s dear sake he took Acrisius out of his dungeon and gave him back his kingdom. For Danae had wept and begged Perseus to rescue his grandfather from prison.

It seemed as though the oracle that long ago had made31 Acrisius act so cruelly would now never be fulfilled. But sooner or later the words of the gods come true.

One day Perseus was present at the games that were held each year at Argos. As he flung a quoit into the air a sudden gust of wind hurled it aside, so that it fell upon the foot of Acrisius, who was sitting near.

The king was an old man now, and the blow was more than he could bear. Before long he died from the wound, and thus the oracle of the gods was fulfilled.

Perseus was kind as he was brave, and it grieved him that he had caused the death of his grandfather, although it had been by no fault of his own.

Argos no longer seemed a happy place to the young king, so he left it, and going to a city called Mycenæ, he made it his capital. Here, after a long and prosperous reign, Perseus died. The gods whom he had served loyally, placed him in the skies, among the stars. And there he still shines, together with Andromeda and Cassiopeia.

32

CHAPTER XI

ACHILLES AND BRISEIS THE FAIRCHEEKED

The story of Perseus belongs to the Heroic Age of Greek history, to the time when heroes were half mortal, half divine. Many other wonderful tales belong to the Heroic Age, but among them all none are so famous as those that are told in the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Iliad tells of the war that raged around the walls of the city of Troy; the Odyssey of the adventures of the goodly Odysseus.

In the north-west corner of Asia, looking toward Greece, the ruins of an ancient city have been discovered. It was on this spot that Troy or Ilium was believed to have stood.

Strange legends gathered round the warriors of the Trojan War, so strange that some people say that there never were such heroes as those of whom the Iliad tells. However that may be, we know that in long after years, when the Greeks fought with the people of Asia, they remembered these old stories, and believed that they were carrying on the wars which their fathers had begun.

The Iliad and the Odyssey were written by a poet named Homer, so many wise folk tell. While others, it may be just as wise, say that these poems were not written by one man, but were gathered from the legends of the people, now by one poet, now by another, until they grew into the collection of stories which we know as the Iliad and the Odyssey.

At first these old stories were not written in a book; they were sung or told in verse by the poets to the people of Hellas. And because what is ‘simple and serious lives longer than what is merely clever,’ these grave old stories of33 two thousand years ago are still alive, and people are still eager to read them.

Some day you will read the Iliad and the Odyssey. In this story I can only tell you about a few of the mighty warriors who fought at Troy, about a few of their strange adventures.

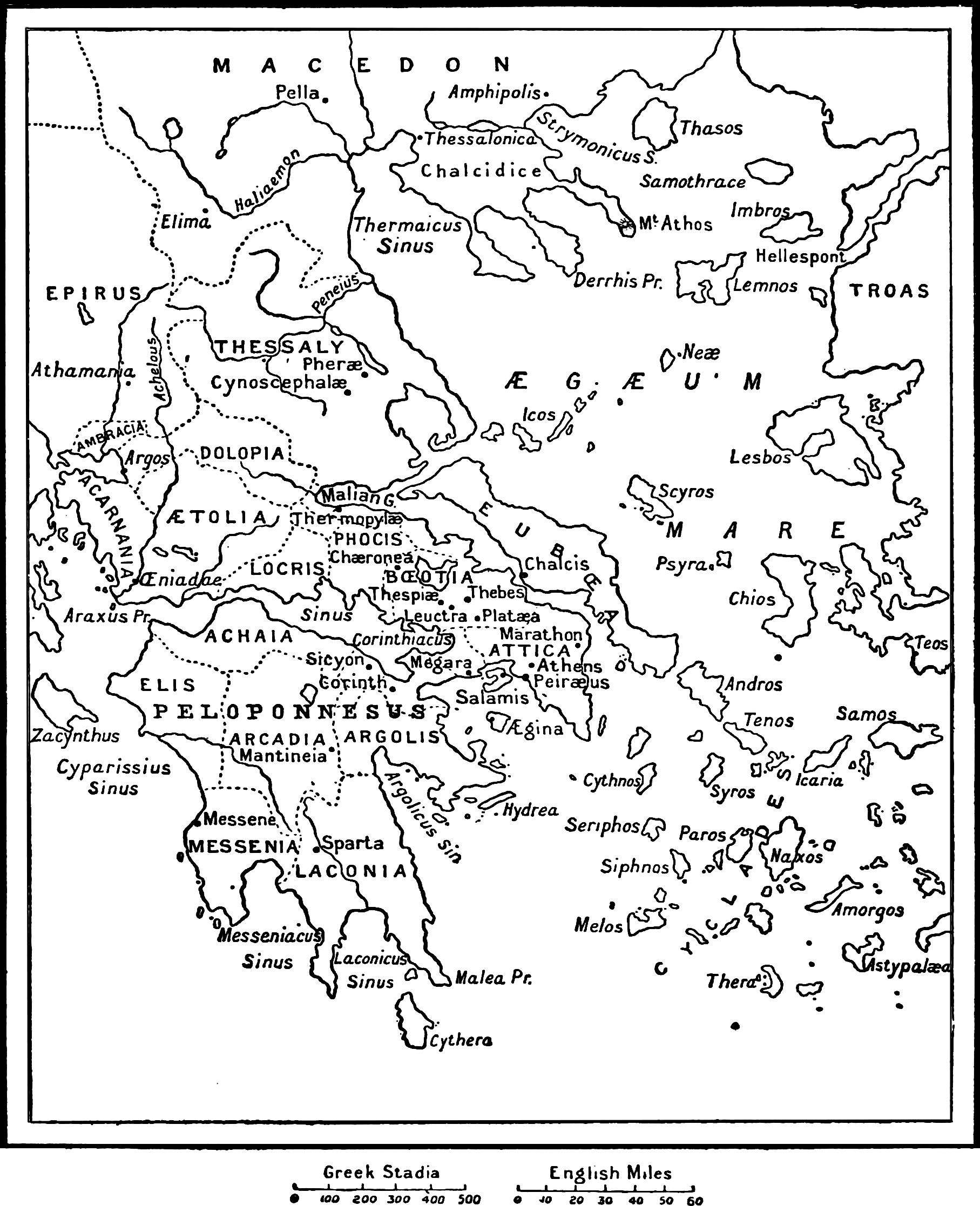

If you look at a map of Greece you will easily find, in the south, the country called Peloponnesus. In Peloponnesus you will see Sparta, the capital city, over which Menelaus was king, when the story of the Iliad begins.

Menelaus was married to a beautiful queen named Helen. She was the fairest woman in the wide world.

One day there came to the court of the king a prince named Paris. He was the second son of Priam, King of Troy. Menelaus welcomed his royal guest and treated him with kindness, but Paris repaid the hospitality of the king most cruelly. For when affairs of State called Menelaus away from Sparta for a short time, Paris did not wait until he returned. He hastened back to Troy, taking with him the beautiful Queen of Sparta, who was ever after known as Helen of Troy.

When Menelaus came home to find that Helen had gone away to Troy, he swore a great oath that he would besiege the city, punish Paris, and bring back his beautiful queen to Sparta; and this was the beginning of the Trojan War.

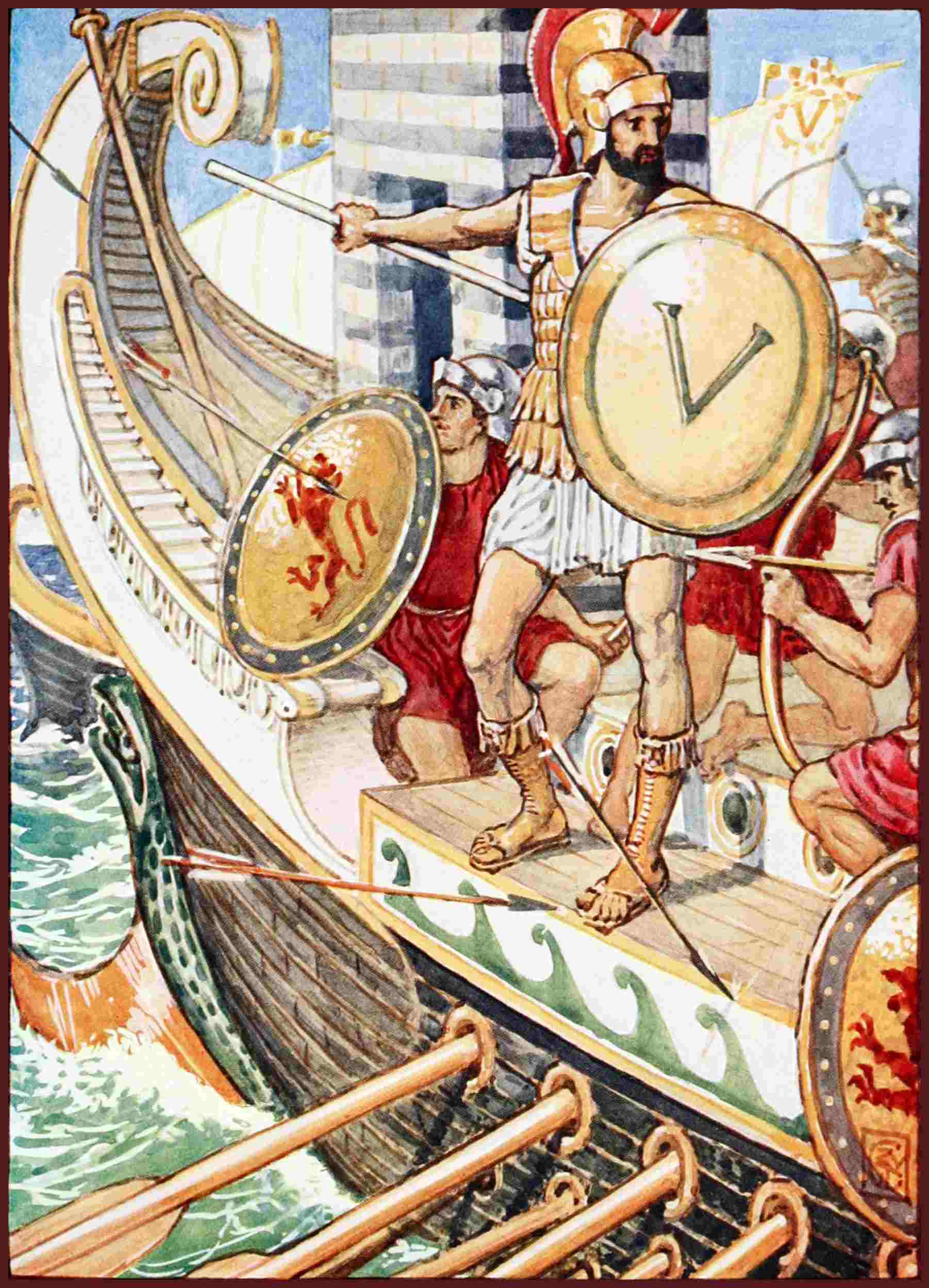

Menelaus had not a large enough army to go alone against his enemy. So he sent to his brother Agamemnon, who was the chief of all the mighty warriors of Hellas, and to many other lords, to beg them to help him to besiege Troy, and, if it might be, to slay Paris.

The chiefs were eager to help Menelaus to avenge his wrongs, and soon a great army was ready to sail across the Hellespont to Asia, to march on Troy.

But before the army embarked, the warriors sent, as was their custom, to an oracle, to ask if their expedition would be successful.

34

‘Without the help of goodly Achilles, Troy will never be taken,’ was the answer.

Achilles was the son of Thetis, the silver-footed goddess, whose home was in the depths of the sea. Well did she love her strong son Achilles. When he was a babe she wished to guard him from the dangers that would surely threaten him when he grew to be a man, so she took him in her arms and carried him to the banks of the river Styx. Whoever bathed in these magic waters became invulnerable, that is, he became proof against every weapon. Silver-footed Thetis, holding her precious babe firmly by one heel, plunged him into the tide, so that his little body became at once invulnerable, save only the heel by which his mother grasped him. It was untouched by the magic water.

Achilles set sail with the other chiefs for Troy, so it seemed as though the city would be taken by his help, as the oracle foretold. With him Achilles took his well-loved friend Patroclus.

For nine long years was the city of Troy besieged, and all for the sake of Helen the beautiful Queen of Sparta. Often as the years passed, she would stand upon the walls of Troy to look at the brave warriors of Hellas, to wonder when they would take the city. But when nine years had passed, no breach had yet been made in the walls.

When the Hellenes needed food or clothing, they attacked and plundered the neighbouring cities, which were not so well defended as Troy.

The plunder of one of these cities, named Chryse, was the cause of the fatal quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles.

In Chryse there was a temple sacred to Apollo, guarded by a priest named Chryses. His daughter Chryseis, and another beautiful maiden named Briseis the Faircheeked, were taken prisoners when the town was sacked by the Hellenes. Agamemnon claimed the daughter of the priest as his share of the spoil, while Briseis he awarded to Achilles.

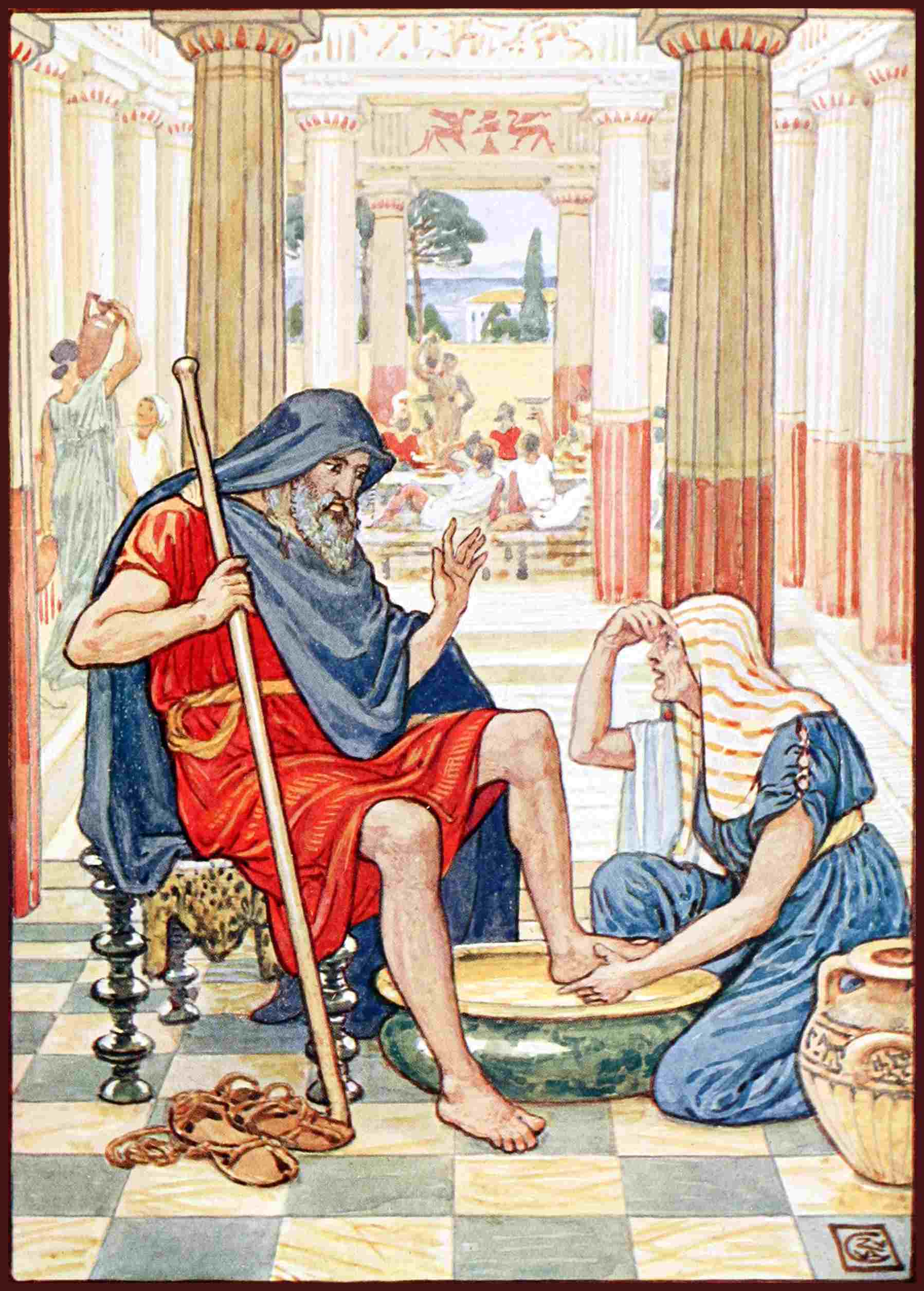

When Chryses the priest found that his daughter had35 been carried away by the Greeks, he hastened to the tent of Agamemnon, taking with him a ransom great ‘beyond telling.’ In his hands he bore a golden staff on which he had placed the holy garland, that the Greeks, seeing it, might treat him with reverence.

‘Now may the gods that dwell in the mansions of Olympus grant you to lay waste the city of Priam and to fare happily homeward,’ said the priest to the assembled chiefs, ‘only set ye my dear child free and accept the ransom in reverence to Apollo.’

All save Agamemnon wished to accept the ransom and set Chryseis free, but he was wroth with the priest and roughly bade him begone.

‘Let me not find thee, old man,’ he cried, ‘amid the ships, whether tarrying now or returning again hereafter, lest the sacred staff of the god avail thee naught. And thy daughter will I not set free. But depart, provoke me not, that thou mayest the rather go in peace.’

Then Chryseis was angry with Agamemnon, while for his daughter’s sake he wept.

Down by the ‘shore of the loud-sounding sea’ he walked, praying to Apollo, ‘Hear me, god of the silver bow. If ever I built a temple gracious in thine eyes, or if ever I burnt to thee fat flesh … of bulls or goats, fulfil thou this my desire; let the Greeks pay by thine arrows for my tears.’

Apollo heard the cry of the priest, and swift was his answer. For he hastened to the tents of the Greeks, bearing upon his shoulders his silver bow, and he sped arrows of death into the camp.

Dogs, mules, men, all fell before the arrows of the angry god. The bodies of the dead were burned on great piles of wood, and the smoke rose black toward the sky.

For nine days the clanging of the silver bow was heard. Then Achilles called the hosts of the Greeks together, and before them all he spoke thus to Agamemnon: ‘Let us go home, Son of Atreus,’ he said, ‘rather than perish, as we surely36 shall do if we remain here. Else let us ask a priest why Apollo treats us thus harshly.’

But it was easy to tell why Apollo was angry, and Calchas, a seer, answered Achilles in plain-spoken words. ‘The wrath of the god is upon us,’ he said, ‘for the sake of the priest whom Agamemnon spurned, refusing to accept the ransom of his daughter. Let Chryseis be sent back to her father, and for sacrifice also a hundred beasts, that the anger of the god may be pacified.’

Deep was the wrath of Agamemnon as he listened to the words of Calchas.

‘Thou seer of evil,’ he cried, his eyes aflame with anger, ‘never yet hast thou told me the thing that is pleasant. Yet that the hosts of our army perish not, I will send the maiden back. But in her place will I take Briseis the Fair-cheeked, whom Achilles has in his tent.’

When Achilles heard these words he drew his sword to slay Agamemnon. But before he could strike a blow he felt the locks of his golden hair caught in a strong grasp, and in a moment his rage was checked, for he knew the touch was that of the goddess Athene. None saw her save Achilles, none heard as she said to him, ‘I came from heaven to stay thine anger…. Go to now, cease from strife, and let not thine hand draw the sword.’

Then Achilles sheathed his sword, saying, ‘Goddess, needs must a man observe thy saying even though he be very wroth at heart, for so is the better way.’

Yet although Achilles struck no blow, bitter were the words he spoke to the king, for a coward did he deem him and full of greed. ‘If thou takest from me Briseis,’ he cried, ‘verily, by my staff, that shall not blossom again seeing it has been cleft from a tree, never will I again draw sword for thee. Surely I and my warriors will go home, for no quarrel have we with the Trojans. And when Hector slaughters thy hosts, in vain shalt thou call for Achilles.’

Well did Agamemnon know that he ought to soothe the37 anger of Achilles and prevail on him to stay, for his presence alone could make the Trojans fear. Yet in his pride the king answered, ‘Thou mayest go and thy warriors with thee. Chieftains have I who will serve me as well as thou, and who will pay me more respect than ever thou hast done. As for the maiden Briseis, her I will have, that the Greeks may know that I am indeed the true sovereign of this host.’

The Assembly then broke up, and Chryseis was sent home under the charge of Odysseus, one of the bravest of the Greek warriors.

When the priest received his daughter again, he at once entreated Apollo to stay his fatal darts, that the Greeks might no longer perish in their camp. And Apollo heard and laid aside his silver bow and his arrows of death.

Then Agamemnon called heralds, and bade them go to the tent of Achilles and bring to him Briseis of the fair cheeks. ‘Should Achilles refuse to give her up,’ said the angry king, ‘let him know that I myself will come to fetch the maiden.’

But when the heralds told Achilles the words of the king, he bade Patroclus bring the damsel from her tent and give her to the messengers of Agamemnon. And the maiden, who would fain have stayed with Achilles, was taken to the king.

38

CHAPTER XII

MENELAUS AND PARIS DO BATTLE

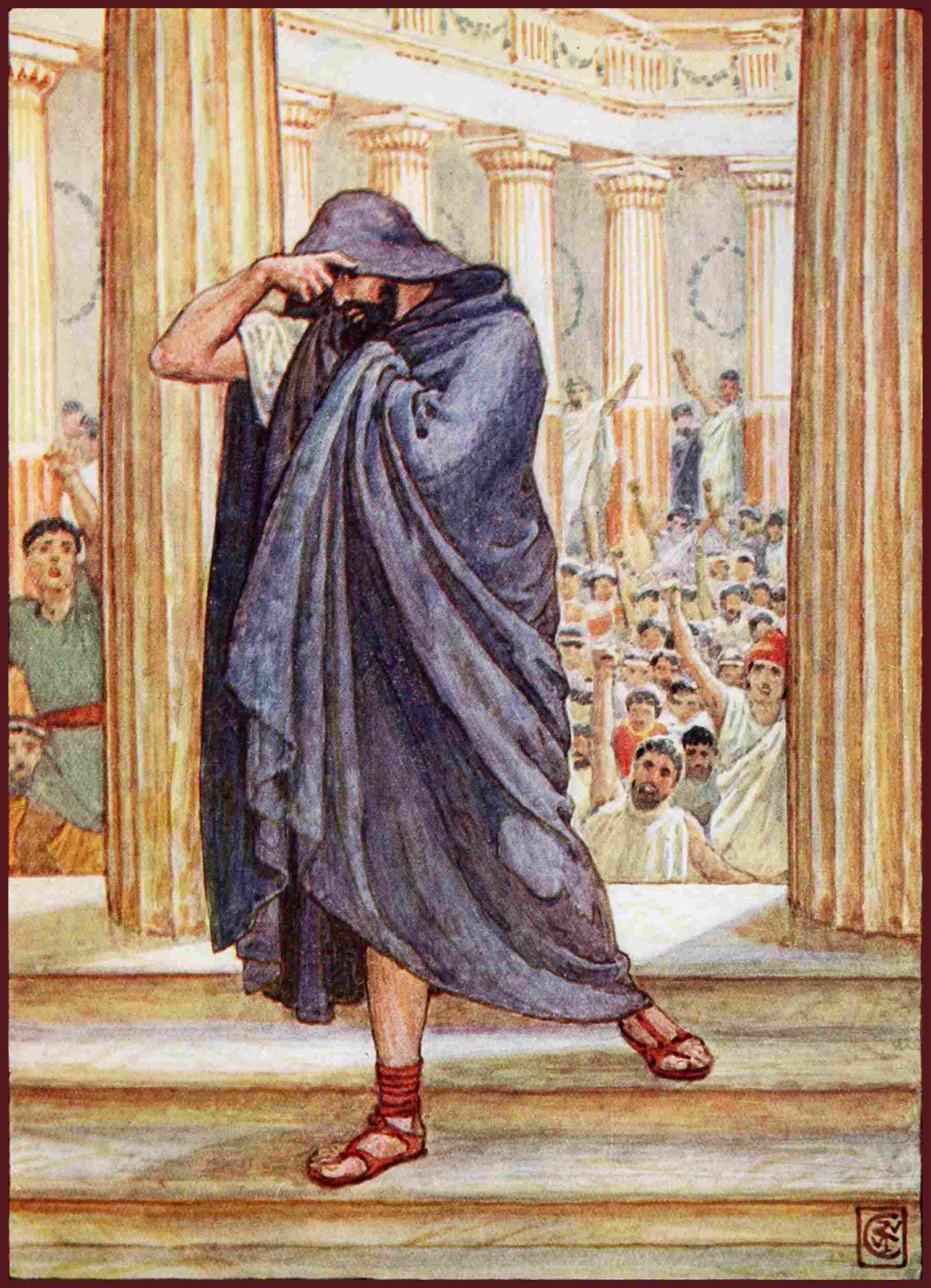

When the heralds of Agamemnon had led Briseis away, Achilles stripped off his armour, for not again would he fight in the Trojan War. Down to the seashore he went alone to weep for the loss of Briseis the Faircheeked.

As he wept he called aloud to his mother Thetis. From the depths of the sea she heard his cry, and swift on a wave she reached the shore. Soon she was by the side of her son, and taking his hand, as when he was a boy, she asked, ‘My child, why weepest thou?’

Then Achilles told how Agamemnon had taken from him Briseis, whom he loved.

‘Go to the palace of Zeus,’ he entreated her, ‘and beseech Zeus to give me honour before the hosts of the Greeks. Let him grant victory to the Trojans until the king sends to Achilles to beg for his help in the battle.’

So Thetis, for the sake of her dear son, hastened to Olympus, and bending at the knee of Zeus she besought the god to avenge the wrong done to Achilles.

At first Zeus, the Cloud-gatherer, was silent, as though he heard her not. ‘Give me now thy promise,’ urged Thetis, ‘and confirm it with a nod or else deny me.’

Then the god nodded, and thereat Olympus shook to its foundations. So Thetis knew that she had found favour in the eyes of Zeus, and leaving the palace of the gods she plunged deep into the sea.

Zeus hastened to fulfil his promise, and sent to Agamemnon a ‘baneful dream.’

39

As the king dreamed, he thought he heard Zeus bid him go forth to battle against the Trojans, for he would surely take the city. But in this Zeus deceived the king.

When Agamemnon awoke in the morning he was glad, for now he hoped to win great honour among his warriors. Quickly he armed himself for battle, throwing a great cloak over his tunic, and slinging his sword, studded with silver, over his shoulder. In his right hand he bore the sceptre of his sires, the sign of his lordship over all the great hosts of Hellas.

Then when he was armed, the king assembled his great army, and after telling his dream, he bade it march in silence toward the city.

But when the Trojans saw the Hellenes drawing near, they came out to meet them ‘with clamour and with shouting like unto birds, even as when there goeth up before heaven a clamour of cranes which flee from the coming of winter and sudden rain.’

As the Trojans approached, Menelaus saw Paris who had stolen his fair wife, and he leaped from his chariot that he might slay the prince. But Paris, when he saw the wrath of Menelaus, was afraid and hid himself among his comrades.

Then Hector, his brother, who was the leader of the Trojans, mocked at him for his cowardice, until Paris grew ashamed.

‘Now will I challenge Menelaus to single combat,’ he cried. And Hector rejoiced at his words and bade the warriors stay their arrows.

‘Hearken, ye Trojans and ye Greeks,’ he cried, ‘Paris bids you lay down your arms while he and his enemy Menelaus alone do battle for Helen and for her wealth. And he who shall be victor shall keep the woman and her treasures, while we will make with one another oaths of friendship and of peace.’ So there, without the walls of the city, oaths were taken both by the Greeks and the Trojans. But the heart of Priam, King of Troy, was heavy lest harm40 should befall Paris, and he hastened within the gates of the city that he might not watch the combat. ‘I can in no wise bear to behold with mine eyes my dear son fighting with Menelaus,’ he said. ‘But Zeus knoweth, and all the immortal gods, for whether of the twain the doom of death is appointed.’

Then Menelaus and Paris drew their swords, and Menelaus cried to Zeus to grant him his aid, so that hereafter men ‘may shudder to wrong his host that hath shown him kindness.’

But it seemed that Zeus heard not, for when Menelaus flung his ponderous spear, although it passed close to Paris, rending his tunic, yet did it not wound him, and when he dealt a mighty blow with his sword upon the helmet of his enemy, lo, his sword broke into pieces in his hand.

Then in his wrath, Menelaus reproached the god: ‘Father Zeus,’ he cried, ‘surely none of the gods is crueller than thou. My sword breaketh in my hand, and my spear sped from my grasp in vain, and I have not smitten my enemy.’

Yet even if Zeus denied his help, Menelaus determined to slay his foe. So he sprang forward and seized Paris by the strap of his helmet. But the goddess Aphrodite flew to the aid of the prince, and the strap broke in the hand of Menelaus. Before the king could again reach his enemy, a mist sent by the goddess concealed the combatants one from the other. Then, unseen by all, Aphrodite caught up Paris, ‘very easily as a goddess may,’ and hid him in the city within his own house.

In vain did Menelaus search for his foe, yet well did he know that no Trojan had given him shelter. For Paris was ‘hated of all even as black death,’ because it was through his base deed that Troy had been besieged for nine long years.

41

CHAPTER XIII

HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE

The gods were angry with Aphrodite because she had hidden Paris from the king, and they determined that, in spite of their oath, the two armies should again begin to fight.

So Athene was sent to the Trojan hosts, disguised as one of themselves. In and out among the soldiers she paced, until at length she spoke to one of them, bidding him draw his bow and wound Menelaus.

The soldier obeyed, and the arrow, guided by Athene, reached the king, yet was the wound but slight.

When the Greeks saw that the Trojans had disregarded their oath, they were full of wrath, and seizing their arms they followed their chiefs to battle. ‘You had thought them dumb, so silent were they,’ as they followed. But as the Trojans looked upon the enemy there arose among them a confused murmur as when ‘sheep bleat without ceasing to hear their lambs cry.’

Fierce and yet more fierce raged the battle. Valiant deeds were done on both sides, but when Hector saw that the Greeks were being helped by the gods, he left the battlefield and hastened to the city.

At the gates, wives and mothers pressed around him, eager to hear what had befallen their husbands, their sons. But Hector tarried only to bid them go pray to the gods.

On to the palace he hastened to find Hecuba, his mother. She, seeing him come, ran to greet him and to beg of him to wait until she brought honey-sweet wine, that he might pour out an offering to Zeus, and himself drink and be refreshed.

42

But Hector said, ‘Bring me no honey-sweet wine, my lady-mother, lest thou cripple me of my courage and I be forgetful of my might. But go thou to the temple with all thy women, to offer gifts to Athene and to beseech her aid.’

Then leaving his mother, Hector went to the house of Paris, and bitterly did he rebuke him, because he was not in the forefront of the battle.

‘Stay but till I arm and I will go with thee,’ answered Paris. But Hector heeded him not, for he was in haste to find his dear wife Andromache and their beautiful boy, Skamandriss. By the people the child was called Astyanax, the City King, for it was his father who guarded Troy.

Andromache was not in their house, but on the wall of the city, watching the battle, fearing lest harm should befall her lord. With her was her little son, in the arms of his nurse.

Hector dared not linger to search for his wife, but as he hastened back to the gates she saw him and ran to bid him farewell ere he returned to battle.

Close to his side she pressed, and her tears fell as she cried:

But Hector, though he dearly loved his wife, could not shrink from the battle. As Andromache ceased to plead43 with him, he held out his arms to his little son, but the child drew back in fear of the great plumes that waved on his father’s shining helmet.

Then Hector took off his helmet and laid it on the ground, while he caught his child in his arms and kissed him, praying Zeus and all the gods to defend him.

Andromache gazed pitifully at her husband as, at length, he gave the child to its nurse, and he seeing her great grief, took her hand and said:

Then springing into his chariot, Hector drove swiftly back to the field of battle.

44

CHAPTER XIV

THE HORSES OF ACHILLES

Hector and Paris reached the battlefield at the same moment. The Trojans were encouraged to fight yet more fiercely when they saw the two princes, and soon so many of the Greeks were slain that Agamemnon grew afraid.

‘Zeus hath sent me a deceiving dream,’ he said to his counsellors. ‘If the gods send not their help we must perish, unless indeed Achilles will forget his anger and come to our aid. Verily, Zeus loveth Achilles, seeing that he putteth the Greeks to flight that he may do him honour. But even as I wronged him in my folly, so will I make amends and give recompence beyond all telling.’

Then, casting aside his pride, the king sent messengers to the tent of Achilles, to say that he would send back Briseis and give to him splendid gifts if he would but come to the help of the Greeks, for they were flying before the enemy.

But the heart of Achilles was too bitter to be touched by the fair promises of the king, for had he not taken from him Briseis, the lady of his love? So he bade the messengers go back to Agamemnon and say that he would not fight, but he would launch his ships on the morrow and sail away to his own land.

When the king heard that Achilles spurned his gifts, and refused to come to his aid, he was afraid. But his counsellors said, ‘Let us not heed Achilles, whether he sail or whether he linger by the loud-sounding sea. When the gods call to him, or when his own heart bids, he will fight. Let us go45 once more against the Trojans, and do thou show thyself, O king, in the forefront of the battle.’

Then Agamemnon rallied his men and led them against the foe, yet again he was driven back. Chief after chief was wounded, and at length the Hellenes fled to their ships to defend them from the Trojans. But Patroclus determined to plead with Achilles to save his countrymen from defeat. When he entered the tent of his friend he was weeping for pity of the dead and wounded.

‘Wherefore weepest thou, Patroclus, like a fond little maid that runs by her mother’s side?’ asked Achilles as he looked up at the entrance of his friend and saw his tears.

‘Never may such wrath take hold of me as that thou nursest, thrice brave, to the hurting of others,’ answered his comrade. ‘The Greeks are lying wounded and dead. If thou wilt not come to their help, let me lead thy men so that the enemy may be beaten back….’

Even as Patroclus pleaded with his friend, a great light flared up against the sky. The Trojans had set fire to the Greek ships.

Then, at length, Achilles was roused. He would not go himself to the help of Agamemnon, but he bade Patroclus put on his armour, while he called together his brave warriors and commanded them to follow his friend to battle.

Quickly Patroclus donned the well-known armour of Achilles, then calling to Automedon, the chariot driver, he bade him harness Xanthus and Balius, the immortal horses of his friend, for their speed was swift as the wind.

As Patroclus vanished from sight in the chariot drawn by Xanthus and Balius, Achilles prayed to Zeus. ‘O Zeus,’ he cried, ‘I send my comrade to this battle. Strengthen his46 heart within him, and when he has driven from the ships the war and din of battle, scathless then let him return to me and my people with him.’

Down upon the Trojans swept the warriors led by Patroclus. They, seeing the armour of Achilles were afraid, and fled from the ships. But ere long they discovered that it was not Achilles but Patroclus who wore the well-known armour, and they returned to fight with new courage. And ever, where the battle raged most fiercely, did Patroclus bid Automedon drive his chariot.

Then the gods bade Hector find Patroclus and slay him. Little trouble had the prince in finding the warrior who wore the armour of Achilles. Bravely the two heroes fought, but Patroclus was not able to stand against the great strength of Hector. Moreover, the gods betrayed him, striking him from behind on the head and shoulders, so that the helmet of Achilles fell in the dust. Apollo also snatched his shield from his arm and broke his spear in two.

When Hector saw that his enemy was disarmed, he took his spear and struck him so fiercely that Patroclus fell

The friend of Achilles was wounded to death.

In his triumph Hector was merciless. He mocked at his fallen foe, saying, ‘Patroclus, surely thou saidst that thou wouldst sack my town, and from Trojan women take away the day of freedom, and bring them in ships to thine own dear country. Fool, … I ward from them the day of destiny, but thee shall vultures here destroy.’

Faint though he was, Patroclus answered, ‘It was not thou, Hector, who didst slay me, but Apollo, who snatched from me my shield and brake my sword in twain.’ Then his strength failed and he breathed his last.

No pity yet showed Hector, for he stripped off the armour of Achilles from the body of Patroclus that he might wear it47 himself. But Zeus, as he looked upon the haughty victor, was displeased.

‘Ah, hapless man,’ said the god to himself, ‘no thought is in thy heart of death that yet draweth nigh unto thee; thou doest on thee the divine armour of a peerless man before whom the rest have terror. His comrade, gentle and brave, thou hast slain, and unmeetly hast stripped the armour from his head and shoulders.’

The immortal horses of Achilles wept when they knew that Patroclus was slain. Automedon lashed them, he spoke kindly to them, yet would they not move. As a pillar on a tomb, so they stood yoked to the chariot. From their eyes big teardrops fell, their beautiful heads hung down with grief so that their long manes were trailed in the dust. Thus sorely did the immortal steeds grieve for the death of Patroclus.

48

CHAPTER XV

THE DEATH OF HECTOR

Fierce and long raged the battle around the body of Patroclus. And while the armies fought, a messenger hastened to the tent of Achilles to tell him that his comrade was slain and that the Trojans fought for his body as it lay naked on the ground, stripped of its armour. ‘Thy armour,’ said the messenger, ‘Hector has taken for himself.’

When Achilles heard the bitter tidings he took dust and poured it with both hands upon his head. ‘As he thought thereon, he shed big tears, now lying on his side, now on his back, now on his face, and then anon he would rise upon his feet, and roam wildly beside the beach of the salt sea.’ As he cried aloud in his grief his mother, Thetis, heard in her home beneath the sea. Swiftly she sped to her son that she might learn why he wept.

Achilles told her all that had befallen Patroclus, and how he himself cared no longer to live, save only that he might slay Hector who had killed his friend.

Thetis bade her son wait but till the morrow before he went to battle, and she would bring him armour made by the great Fire-god.

Then she left him and prayed the god Hephaestus, keeper of the forge, to give her armour for her dear son.

Hephaestus was pleased to work for so goodly a warrior as Achilles. Quickly he set his twenty bellows to work, and when the fire blazed in the forge, he threw into it bronze and silver and gold. Then taking a great hammer in his hand he fashioned a marvellous shield, more marvellous than words49 can tell. Before morning a complete suit of armour was ready for Achilles.

Meanwhile Hector had all but captured the body of Patroclus. But the gods spoke to Achilles, bidding him now succour the body of his friend. Without armour Achilles could not enter the fray, yet he hastened to the trenches that the Trojans might see him.

Around his head gleamed a golden light, placed there by Athene. When the Trojans saw the flame and heard the mighty cry of Achilles, they drew back afraid.

Three times the warrior shouted, and three times the Trojans drew back in fear. While they hesitated the Greeks rushed forward and carried away the body of Patroclus, nor did they lay it down until they laid it in the tent of Achilles.

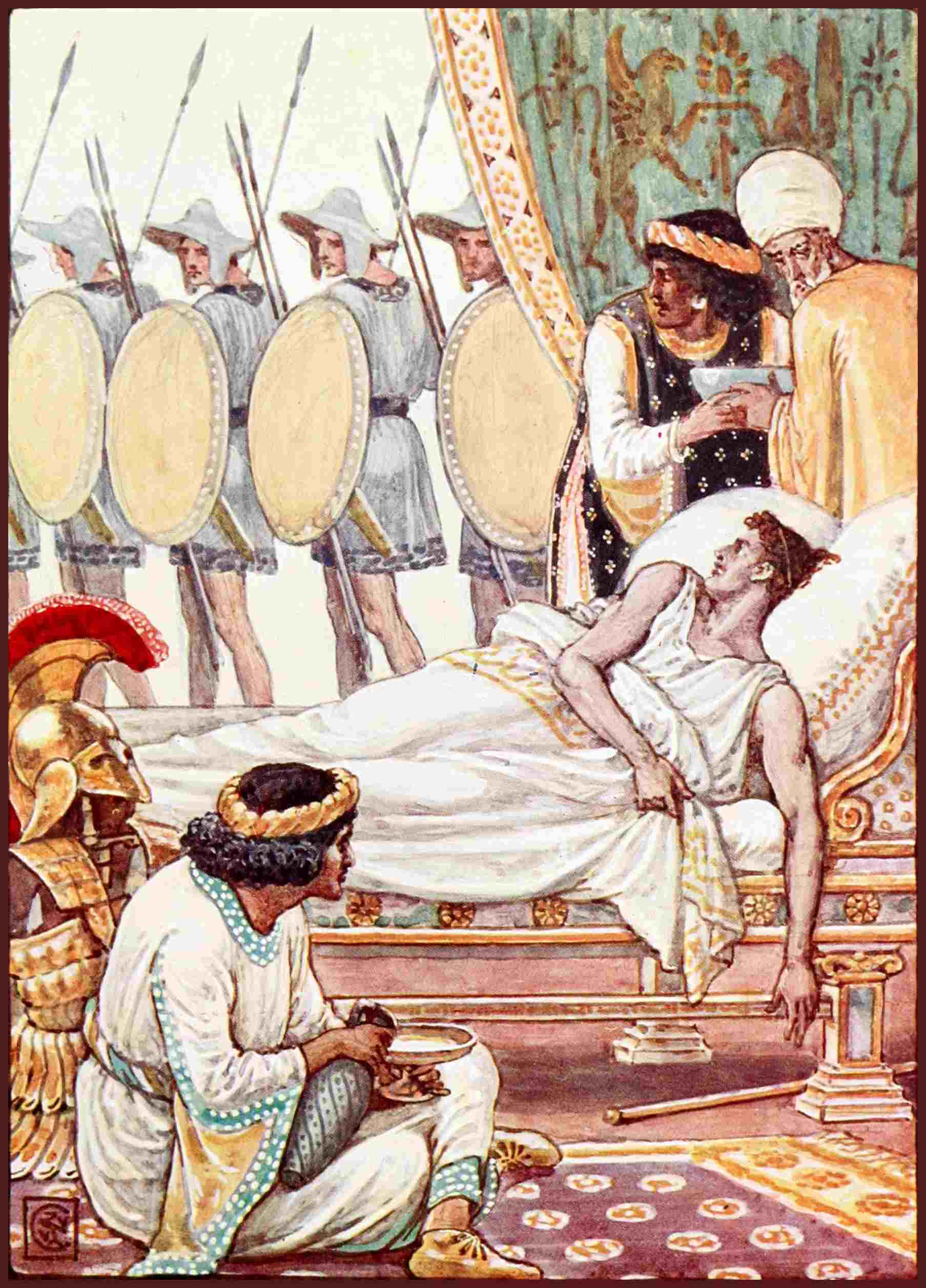

On the morrow Thetis came back to her son, bringing with her the armour made by Hephaestus. She found him weeping over the body of his friend.

‘My child,’ she said, ‘him who lieth here we must let be, for all our pain. Arm thyself now and go thy way into the fray.’

Then Achilles put on the armour of the god in haste, for he feared lest another than he should slay Hector.

With Achilles once again at their head, the Greek warriors attacked the Trojans with redoubled fury. But it was Hector alone whom Achilles longed to meet, and soon he saw his enemy near one of the gates of Troy. Now he would avenge the death of Patroclus. But when Hector saw the great hate in the eyes of his enemy, lo, he turned and fled.

‘As a hawk, fastest of all the birds of air, pursues a dove upon the mountains,’ so did Achilles pursue the prince until he was forced to stand to take breath. Then Hector, encouraged by the gods, drew near to him and spoke, ‘Thrice, great Achilles, hast thou pursued me round the walls of Troy, and I dared not stand up against thee; but now I fear thee50 no more. Only do thou promise, if Zeus give thee the victory, to do no dishonour to my body, as I also will promise to do none to thine should I slay thee.’

But Achilles, remembering Patroclus, cried out in anger that never would he make a covenant with him who had slain his friend.

Then with fierce blows each fell upon the other, until at length Achilles drove his spear through the armour that Hector wore, and the Trojan prince fell, stricken to the ground.

Achilles, his anger still burning fiercely, stripped the dead man of his armour, while many Greek warriors standing near thrust at him with their spears, saying to one another, ‘Go to, for easier to handle is Hector now, than when he burnt the ships with blazing fire.’

Then Achilles tied the dead man to his chariot with thongs of ox-hide and drove nine times round the city walls, dragging the fair head of Hector in the dust.

From the tower Priam and Hecuba saw the body of their son dragged in the dust, and bitter was their pain.

But Andromache knew not yet what had befallen her lord, for she sat in an inner chamber wearing a purple cloth. Soon she bade her maids prepare a bath for Hector, for she thought that he would return ere long from the battle. She knew not yet that Hector would never return, but as the noise of the wailing of the people reached the room in which she sat, her heart misgave her. In haste she ran to the wall of the city, only to see the chariot of Achilles as it dragged Hector down to the loud-sounding sea.

Then fainting with grief, Andromache fell to the ground, and the diadem which Aphrodite had given to her on her wedding morn dropped from her head, to be worn by her no more.

Down by the seashore Achilles burned the body of Patroclus with great honour, and when the funeral rites were51 ended, he dragged the dead body of Hector round the tomb, weeping for the loss of his dear comrade.

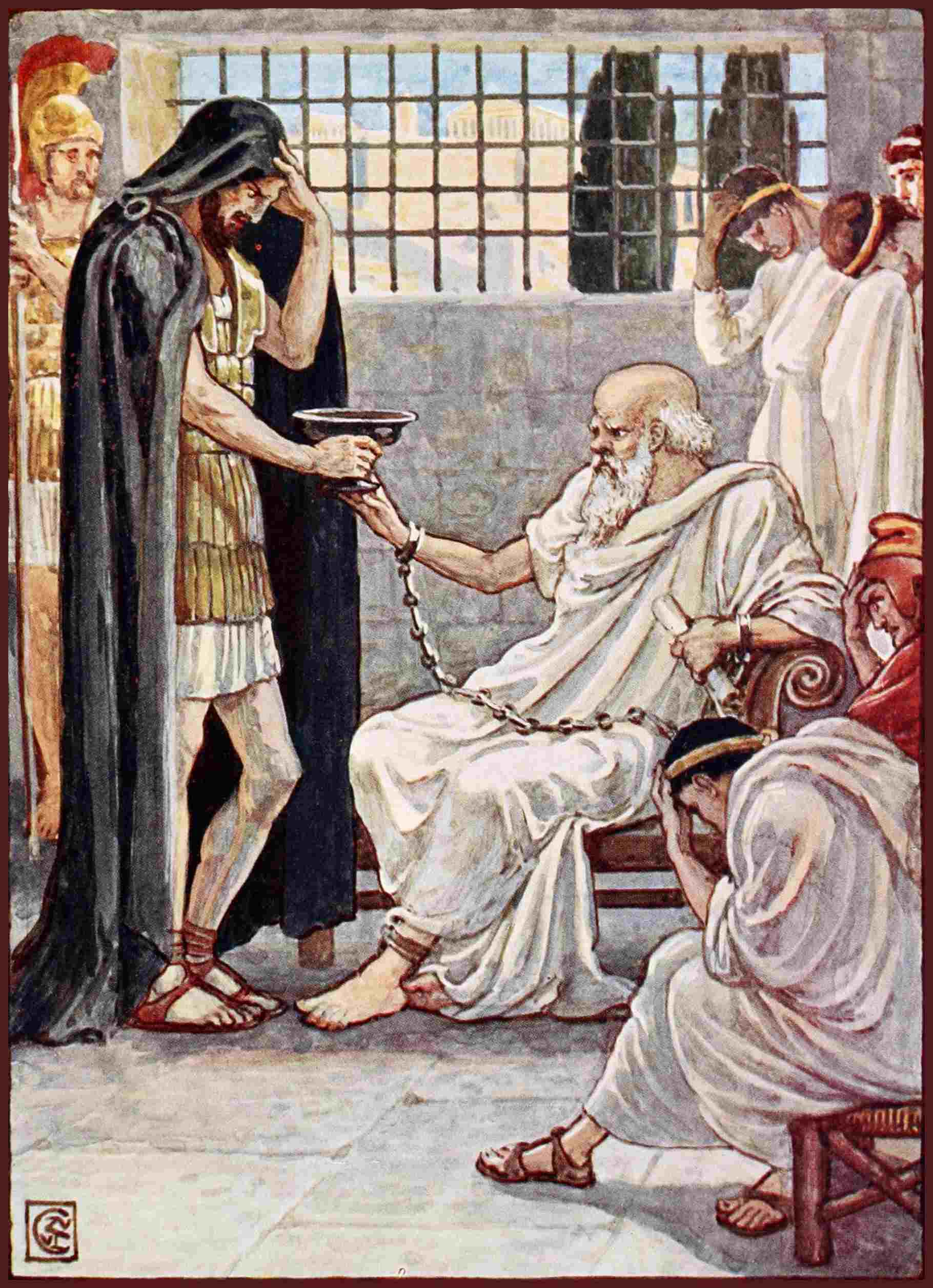

But Zeus was angry with Achilles for treating the Trojan prince so cruelly, and he sent Thetis to bid her son give back Hector’s body to Priam, who would come to offer for it a ransom. ‘If Zeus decrees it, whoever brings a ransom shall return with the dead,’ answered Achilles.

Then Zeus sent a messenger to the house of Priam, where the mother and the wife of Hector wept, saying, ‘Be of good cheer in thy heart, O Priam…. I am the messenger of Zeus to thee, who though he be afar off, hath great care and pity for thee. The Olympian biddeth thee ransom noble Hector’s body, and carry gifts to Achilles that may gladden his heart.’

So Priam set out alone, save for the driver of the wagon which was to bring Hector again to Troy, for so had the messenger commanded. But Hecuba feared to let the old man go alone to the tent of the enemy. When he reached the camp of the Greeks, Priam hastened to the tent of Achilles, and entering it before his enemy was aware, the old king fell at the feet of his enemy and begged for the body of his dear son.

Achilles could not look upon the grief of the old man unmoved, but when Priam offered him gifts he frowned and haughtily he answered, ‘Of myself am I minded to give Hector back to thee, for so has Zeus commanded.’

Then a truce for nine days was made between the Greeks and the Trojans, so that King Priam and his people might mourn for Hector and bury him undisturbed by fear of the enemy.

Priam tarried with Achilles until night fell. Then while he and his warriors slept, the king arose and bade the driver yoke the horses and mules. When this was done they laid the body of Hector upon the wagon, and in the silence of the night set out on their homeward journey.

At the gates of Troy stood Andromache and Hecuba52 watching until Priam returned. And when the wagon reached the city the Trojans carried Hector into his own house. Then Andromache took the head of her dear husband in her arms and said, ‘Husband, thou art gone young from life and leavest me a widow in thy halls. And the child is yet but a little one … nor methinks shall he grow up to manhood, for ere then shall this city be utterly destroyed. For thou art verily perished who didst watch over it and guard it, and keptest safe its noble wives and infant little ones.’

The following morning Priam bade his people go gather wood for the burial, and after nine days the body of Hector was laid on the pile and burned. Then his white bones, wrapped in purple cloth, were placed in a golden chest. Above the chest a great mound was raised, and thus Hector, the brave prince of Troy, was buried.

Soon after the burial of Hector Achilles was killed by a poisoned arrow which Paris aimed at his heel, the one spot of his body that Thetis had failed to bathe in the magic waters of the river Styx. Paris himself perished soon after the death of Achilles.

Troy still remained untaken. Then goodly Odysseus told the Greeks that although they could not take the city by storm, they might take her by a stratagem or trick.