HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE CHEROKEE

The Traditionary Period

“The Cherokee were the mountaineers of the South, holding the entire Allegheny region from the interlocking head-streams of the Kanawha and the Tennessee southward almost to the site of Atlanta, and from the Blue ridge on the east to the Cumberland range on the west, a territory comprising an area of about 40,000 square miles, now included in the states of Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. Their principal towns were upon the headwaters of the Savannah, Hiwassee, and Tuckasegee, and along the whole length of the Little Tennessee to its junction with the main stream. Itsâtĭ, or Echota, on the south bank of the Little Tennessee, a few miles above the mouth of Tellico river, in Tennessee, was commonly considered the capital of the Nation. As the advancing whites pressed upon them from the east and northeast the more exposed towns were destroyed or abandoned and new settlements were formed lower down the Tennessee and on the upper branches of the Chattahoochee and the Coosa. …

“Cherokee, the name by which they are commonly known, has no meaning in their own language, and seems to be of foreign origin. As used among themselves the form is Tsa′lăgĭ′ or Tsa′răgĭ′. It first appears as Chalaque in the Portuguese narrative of De Soto’s expedition, published originally in 1557, while we find Cheraqui in a French document of 1699, and Cherokee as an English form as early, at least, as 1708. The name has thus an authentic history of 360 years. There is evidence that it is derived from the Choctaw word choluk or chiluk, signifying a pit or cave, and comes to us through the so-called Mobilian trade language, a corrupted Choctaw jargon formerly used as the [16]medium of communication among all the tribes of the Gulf states, as far north as the mouth of the Ohio (2). Within this area many of the tribes were commonly known under Choctaw names, even though of widely differing linguistic stocks, and if such a name existed for the Cherokee it must undoubtedly have been communicated to the first Spanish explorers by De Soto’s interpreters. This theory is borne out by their Iroquois (Mohawk) name, Oyataʼgeʻronoñʼ, as given by Hewitt, signifying “inhabitants of the cave country,” the Allegheny region being peculiarly a cave country, in which “rock shelters,” containing numerous traces of Indian occupancy, are of frequent occurrence. Their Catawba name also, Mañterañ, as given by Gatschet, signifying “coming out of the ground,” seems to contain the same reference. Adair’s attempt to connect the name Cherokee with their word for fire, atsila, is an error founded upon imperfect knowledge of the language.

…

“The Iroquoian stock, to which the Cherokee belong, had its chief home in the north, its tribes occupying a compact territory which comprised portions of Ontario, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, and extended down the Susquehanna and Chesapeake bay almost to the latitude of Washington. Another body, including the Tuscarora, Nottoway, and perhaps also the Meherrin, occupied territory in northeastern North Carolina and the adjacent portion of Virginia. The Cherokee themselves constituted the third and southernmost body. It is evident that tribes of common stock must at one time have occupied contiguous territories,

The Wyandot confirm the Delaware story and fix the identification of the expelled tribe. According to their tradition, as narrated in 1802, the ancient fortifications in the Ohio valley had been erected in the course of a long war between themselves and the Cherokee, which resulted finally in the defeat of the latter.5 …

The Period of Spanish Exploration—1540–?

[The Lady of Cofitachequi]

“The definite history of the Cherokee begins with the year 1540, at which date we find them already established, where they were always afterward known, in the mountains of Carolina and Georgia. The earliest Spanish adventurers failed to penetrate so far into the interior, and the first entry into their country was made by De Soto, advancing up the Savannah on his fruitless quest for gold, in May of that year.

While at Cofitachiqui, an important Indian town on the lower Savannah governed by a “queen,” the Spaniards had found hatchets and other objects of copper, some of which was of finer color and appeared to be mixed with gold, although they had no means of testing it.17 On inquiry they were told that the metal had come from an interior mountain province called Chisca, but the country was represented as thinly peopled and the way as impassable for horses. Some time before, while advancing through eastern Georgia, they had heard also of a rich and plentiful province called Coça, toward the northwest, and by the people of Cofitachiqui they were now told that Chiaha, the nearest town of Coça province, was twelve days inland. As both men and animals were already nearly exhausted from hunger and hard travel, and the Indians either could not or would not furnish sufficient provision for their needs, De Soto determined not to attempt the passage of the mountains then, but to push on at once to Coça, there to rest and recuperate before undertaking further exploration. In the meantime [24]he hoped also to obtain more definite information concerning the mines. As the chief purpose of the expedition was the discovery of the mines, many of the officers regarded this change of plan as a mistake, and favored staying where they were until the new crop should be ripened, then to go directly into the mountains, but as the general was “a stern man and of few words,” none ventured to oppose his resolution.18 The province of Coça was the territory of the Creek Indians, called Ani′-Kusa by the Cherokee, from Kusa, or Coosa, their ancient capital, while Chiaha was identical with Chehaw, one of the principal Creek towns on Chattahoochee river. Cofitachiqui may have been the capital of the Uchee Indians.

“The outrageous conduct of the Spaniards had so angered the Indian queen that she now refused to furnish guides and carriers, whereupon De Soto made her a prisoner, with the design of compelling her to act as guide herself, and at the same time to use her as a hostage to command the obedience of her subjects. Instead, however, of conducting the Spaniards by the direct trail toward the west, she led them far out of their course until she finally managed to make her escape, leaving them to find their way out of the mountains as best they could. ..

STORIES AND STORY TELLERS

“Cherokee myths may be roughly classified as sacred myths, animal stories, local legends, and historical traditions.

Sacred Myths

Creation Stories

To the first class belong the genesis stories, dealing with the creation of the world, the nature of the heavenly bodies and elemental forces, the origin of life and death, the spirit world and the invisible beings, the ancient monsters, and the hero-gods. It is almost certain that most of the myths of this class are but disjointed fragments of an original complete genesis and migration legend, which is now lost. With nearly every tribe that has been studied we find such a sacred legend, preserved by the priests of the tradition, who alone are privileged to recite and explain it, and dealing with the origin and wanderings of the people from the beginning of the world to the final settlement of the tribe in its home territory. Among the best examples of such genesis traditions are those recorded in the Walam Olum of the Delawares and Matthews’ Navaho Origin Legend. Others may be found in Cusick’s History of the Six Nations, Gatschet’s Creek Migration Legend, and the author’s Jicarilla Genesis.1 The Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other plains tribes are known to have similar genesis myths. …

“The sacred myths were not for every one, but only those might hear who observed the proper form and ceremony. When John Ax and [230]other old men were boys, now some eighty years ago, the myth-keepers and priests were accustomed to meet together at night in the âsĭ, or low-built log sleeping house, to recite the traditions and discuss their secret knowledge. …

“At daybreak the whole party went down to the running stream, where the pupils or hearers of the myths stripped themselves, and were scratched upon their naked skin with a bone-tooth comb in the hands of the priest, after which they waded out, facing the rising sun, and dipped seven times under the water, while the priest recited prayers upon the bank. This purificatory rite, observed more than a century ago by Adair, is also a part of the ceremonial of the ballplay, the Green-corn dance, and, in fact, every important ritual performance. Before beginning one of the stories of the sacred class the informant would sometimes suggest jokingly that the author first submit to being scratched and “go to water.”

“As a special privilege a boy was sometimes admitted to the âsĭ on such occasions, to tend the fire, and thus had the opportunity to listen to the stories and learn something of the secret rites. In this way John Ax gained much of his knowledge, although he does not claim to be an adept. As he describes it, the fire intended to heat the room—for the nights are cold in the Cherokee mountains—was built upon the ground in the center of the small house, which was not high enough to permit a standing position, while the occupants sat in a circle around it. In front of the fire was placed a large flat rock, and near it a pile of pine knots or splints. When the fire had burned down to a bed of coals, the boy lighted one or two of the pine knots and laid them upon the rock, where they blazed with a bright light until nearly consumed, when others were laid upon them, and so on until daybreak.

Animal Myths

‘To the second class belong the shorter animal myths, which have lost whatever sacred character they may once have had, and are told now merely as humorous explanations of certain animal peculiarities. While the sacred myths have a constant bearing upon formulistic prayers and observances, it is only in rare instances that any rite or custom is based upon an animal myth. Moreover, the sacred myths are known as a rule only to the professional priests or conjurers, while the shorter animal stories are more or less familiar to nearly everyone and are found in almost identical form among Cherokee, Creeks, and other southern tribes.

“The animals of the Cherokee myths, like the traditional hero-gods, were larger and of more perfect type than their present representatives. They had chiefs, councils, and townhouses, mingled with human kind upon terms of perfect equality and spoke the same language. In some unexplained manner they finally left this lower world and ascended to Galûñ′lătĭ, the world above, where they still exist. The removal was not simultaneous, but each animal chose his own time. The animals that we know, small in size and poor in intellect, came upon the earth later, and are not the descendants of the mythic animals, but only weak imitations. In one or two special cases, however, the present creature is the descendant of a former monster. Trees and plants also were alive and could talk in the old days, and had their place in council, but do not figure prominently in the myths.

The Frog Was the Leader

“Each animal had his appointed station and duty. Thus, the Walâ′sĭ frog was the marshal and leader in the council,

The Rabbit Was the Messenger and Led the Dance–Also the Trickster

while the Rabbit was the messenger to carry all public announcements, and usually led the dance besides. He was also the great trickster and mischief maker, a character which he bears in eastern and southern Indian myth generally, as well as in the southern negro stories.

The Bear Was Originally a Man

“The bear figures as having been originally a man, with human form and nature

Nature Myths

“As with other tribes and countries, almost every prominent rock and mountain, every deep bend in the river, in the old Cherokee country has its accompanying legend.” Mooney, James. Myths of the Cherokees

Lyrics:

“You think you own whatever land you land onThe Earth is just a dead thing you can claimBut I know every rock and tree and creatureHas a life, has a spirit, has a name …

“It may be a little story that can be told in a paragraph, to account for some natural feature, or it may be one chapter of a myth that has its sequel in a mountain a hundred miles away. As is usual when a people has lived for a long time in the same country, nearly every important myth is localized, thus assuming more definite character. …

“With some tribes the winter season and the night are the time for telling stories, but to the Cherokee all times are alike. As our grandmothers begin, “Once upon a time,” so the Cherokee story-teller introduces his narrative by saying: “This is what the old men told me when I was a boy.” …

THE MYTHS

Cosmogonic Myths

1. HOW THE WORLD WAS MADE

“The earth is a great island floating in a sea of water, and suspended at each of the four cardinal points by a cord hanging down from the sky vault, which is of solid rock. When the world grows old and worn out, the people will die and the cords will break and let the earth sink down into the ocean, and all will be water again. The Indians are afraid of this.

When all was water, the animals were above in Gălûñ′lătĭ, beyond the arch; but it was very much crowded, and they were wanting more room. They wondered what was below the water, and at last Dâyuni′sĭ, “Beaver’s Grandchild,” the little Water-beetle, offered to go and see if it could learn. It darted in every direction over the surface of the water, but could find no firm place to rest. Then it dived to the bottom and came up with some soft mud, which began to grow and spread on every side until it became the island which we call the earth. It was afterward fastened to the sky with four cords, but no one remembers who did this.

At first the earth was flat and very soft and wet. The animals were anxious to get down, and sent out different birds to see if it was yet dry, but they found no place to alight and came back again to Gălûñ′lătĭ. At last it seemed to be time, and they sent out the Buzzard and told him to go and make ready for them. This was the Great Buzzard, the father of all the buzzards we see now. He flew all over the earth, low down near the ground, and it was still soft. When he reached the Cherokee country, he was very tired, and his wings began to flap and strike the ground, and wherever they struck the earth there was a valley, and where they turned up again there was a mountain. When the animals above saw this, they were afraid that the whole world would be mountains, so they called him back, but the Cherokee country remains full of mountains to this day.

When the earth was dry and the animals came down, it was still dark, so they got the sun and set it in a track to go every day across the island from east to west, just overhead. It was too hot this way, and Tsiska′gĭlĭ′, the Red Crawfish, had his shell scorched a bright red, so that his meat was spoiled; and the Cherokee do not eat it. The [240]conjurers put the sun another hand-breadth higher in the air, but it was still too hot. They raised it another time, and another, until it was seven handbreadths high and just under the sky arch. Then it was right, and they left it so. This is why the conjurers call the highest place Gûlkwâ′gine Di′gălûñ′lătiyûñ′, “the seventh height,” because it is seven hand-breadths above the earth. Every day the sun goes along under this arch, and returns at night on the upper side to the starting place.

There is another world under this, and it is like ours in everything—animals, plants, and people—save that the seasons are different. The streams that come down from the mountains are the trails by which we reach this underworld, and the springs at their heads are the doorways by which we enter it, but to do this one must fast and go to water and have one of the underground people for a guide. We know that the seasons in the underworld are different from ours, because the water in the springs is always warmer in winter and cooler in summer than the outer air.

When the animals and plants were first made—we do not know by whom—they were told to watch and keep awake for seven nights, just as young men now fast and keep awake when they pray to their medicine. They tried to do this, and nearly all were awake through the first night, but the next night several dropped off to sleep, and the third night others were asleep, and then others, until, on the seventh night, of all the animals only the owl, the panther, and one or two more were still awake. To these were given the power to see and to go about in the dark, and to make prey of the birds and animals which must sleep at night. Of the trees only the cedar, the pine, the spruce, the holly, and the laurel were awake to the end, and to them it was given to be always green and to be greatest for medicine, but to the others it was said: “Because you have not endured to the end you shall lose your hair every winter.”

Men came after the animals and plants. At first there were only a brother and sister until he struck her with a fish and told her to multiply, and so it was. In seven days a child was born to her, and thereafter every seven days another, and they increased very fast until there was danger that the world could not keep them. Then it was made that a woman should have only one child in a year, and it has been so ever since.

2. THE FIRST FIRE

In the beginning there was no fire, and the world was cold, until the Thunders (Ani′-Hyûñ′tĭkwălâ′skĭ), who lived up in Gălûñ′lătĭ, sent their lightning and put fire into the bottom of a hollow sycamore tree which grew on an island. The animals knew it was there, because they could see the smoke coming out at the top, but they could not get to it on [241]account of the water, so they held a council to decide what to do. This was a long time ago.

Every animal that could fly or swim was anxious to go after the fire. The Raven offered, and because he was so large and strong they thought he could surely do the work, so he was sent first. He flew high and far across the water and alighted on the sycamore tree, but while he was wondering what to do next, the heat had scorched all his feathers black, and he was frightened and came back without the fire. The little Screech-owl (Wa′huhu′) volunteered to go, and reached the place safely, but while he was looking down into the hollow tree a blast of hot air came up and nearly burned out his eyes. He managed to fly home as best he could, but it was a long time before he could see well, and his eyes are red to this day. Then the Hooting Owl (U′guku′) and the Horned Owl (Tskĭlĭ′) went, but by the time they got to the hollow tree the fire was burning so fiercely that the smoke nearly blinded them, and the ashes carried up by the wind made white rings about their eyes. They had to come home again without the fire, but with all their rubbing they were never able to get rid of the white rings.

Now no more of the birds would venture, and so the little Uksu′hĭ snake, the black racer, said he would go through the water and bring back some fire. He swam across to the island and crawled through the grass to the tree, and went in by a small hole at the bottom. The heat and smoke were too much for him, too, and after dodging about blindly over the hot ashes until he was almost on fire himself he managed by good luck to get out again at the same hole, but his body had been scorched black, and he has ever since had the habit of darting and doubling on his track as if trying to escape from close quarters. He came back, and the great blacksnake, Gûle′gĭ, “The Climber,” offered to go for fire. He swam over to the island and climbed up the tree on the outside, as the blacksnake always does, but when he put his head down into the hole the smoke choked him so that he fell into the burning stump, and before he could climb out again he was as black as the Uksu′hĭ.

Now they held another council, for still there was no fire, and the world was cold, but birds, snakes, and four-footed animals, all had some excuse for not going, because they were all afraid to venture near the burning sycamore, until at last Kănăne′skĭ Amai′yĕhĭ (the Water Spider) said she would go. This is not the water spider that looks like a mosquito, but the other one, with black downy hair and red stripes on her body. She can run on top of the water or dive to the bottom, so there would be no trouble to get over to the island, but the question was, How could she bring back the fire? “I’ll manage that,” said the Water Spider; so she spun a thread from her body and wove it into a tusti bowl, which she fastened on her back. Then she crossed over to the island and through the grass to where the fire was [242]still burning. She put one little coal of fire into her bowl, and came back with it, and ever since we have had fire, and the Water Spider still keeps her tusti bowl.

3. KANA′TĬ AND SELU: THE ORIGIN OF GAME AND CORN

When I was a boy this is what the old men told me they had heard when they were boys.

Long years ago, soon after the world was made, a hunter and his wife lived at Pilot knob with their only child, a little boy. The father’s name was Kana′tĭ (The Lucky Hunter), and his wife was called Selu (Corn). No matter when Kana′tĭ went into the wood, he never failed to bring back a load of game, which his wife would cut up and prepare, washing off the blood from the meat in the river near the house. The little boy used to play down by the river every day, and one morning the old people thought they heard laughing and talking in the bushes as though there were two children there. When the boy came home at night his parents asked him who had been playing with him all day. “He comes out of the water,” said the boy, “and he calls himself my elder brother. He says his mother was cruel to him and threw him into the river.” Then they knew that the strange boy had sprung from the blood of the game which Selu had washed off at the river’s edge.

Every day when the little boy went out to play the other would join him, but as he always went back again into the water the old people never had a chance to see him. At last one evening Kana′tĭ said to his son, “Tomorrow, when the other boy comes to play, get him to wrestle with you, and when you have your arms around him hold on to him and call for us.” The boy promised to do as he was told, so the next day as soon as his playmate appeared he challenged him to a wrestling match. The other agreed at once, but as soon as they had their arms around each other, Kana′tĭ’s boy began to scream for his father. The old folks at once came running down, and as soon as the Wild Boy saw them he struggled to free himself and cried out, “Let me go; you threw me away!” but his brother held on until the parents reached the spot, when they seized the Wild Boy and took him home with them. They kept him in the house until they had tamed him, but he was always wild and artful in his disposition, and was the leader of his brother in every mischief. It was not long until the old people discovered that he had magic powers, and they called him I′năge-utăsûñ′hĭ (He-who-grew-up-wild).

Whenever Kana′tĭ went into the mountains he always brought back a fat buck or doe, or maybe a couple of turkeys. One day the Wild Boy said to his brother, “I wonder where our father gets all that game; let’s follow him next time and find out.” A few days afterward Kana′tĭ took a bow and some feathers in his hand and started off [243]toward the west. The boys waited a little while and then went after him, keeping out of sight until they saw him go into a swamp where there were a great many of the small reeds that hunters use to make arrowshafts. Then the Wild Boy changed himself into a puff of bird’s down, which the wind took up and carried until it alighted upon Kana′tĭ’s shoulder just as he entered the swamp, but Kana′tĭ knew nothing about it. The old man cut reeds, fitted the feathers to them and made some arrows, and the Wild Boy—in his other shape—thought, “I wonder what those things are for?” When Kana′tĭ had his arrows finished he came out of the swamp and went on again. The wind blew the down from his shoulder, and it fell in the woods, when the Wild Boy took his right shape again and went back and told his brother what he had seen. Keeping out of sight of their father, they followed him up the mountain until he stopped at a certain place and lifted a large rock. At once there ran out a buck, which Kana′tĭ shot, and then lifting it upon his back he started for home again. “Oho!” exclaimed the boys, “he keeps all the deer shut up in that hole, and whenever he wants meat he just lets one out and kills it with those things he made in the swamp.” They hurried and reached home before their father, who had the heavy deer to carry, and he never knew that they had followed.

A few days later the boys went back to the swamp, cut some reeds, and made seven arrows, and then started up the mountain to where their father kept the game. When they got to the place, they raised the rock and a deer came running out. Just as they drew back to shoot it, another came out, and then another and another, until the boys got confused and forgot what they were about. In those days all the deer had their tails hanging down like other animals, but as a buck was running past the Wild Boy struck its tail with his arrow so that it pointed upward. The boys thought this good sport, and when the next one ran past the Wild Boy struck its tail so that it stood straight up, and his brother struck the next one so hard with his arrow that the deer’s tail was almost curled over his back. The deer carries his tail this way ever since. The deer came running past until the last one had come out of the hole and escaped into the forest. Then came droves of raccoons, rabbits, and all the other four-footed animals—all but the bear, because there was no bear then. Last came great flocks of turkeys, pigeons, and partridges that darkened the air like a cloud and made such a noise with their wings that Kana′tĭ, sitting at home, heard the sound like distant thunder on the mountains and said to himself, “My bad boys have got into trouble; I must go and see what they are doing.”

So he went up the mountain, and when he came to the place where he kept the game he found the two boys standing by the rock, and all the birds and animals were gone. Kana′tĭ was furious, but without [244]saying a word he went down into the cave and kicked the covers off four jars in one corner, when out swarmed bedbugs, fleas, lice, and gnats, and got all over the boys. They screamed with pain and fright and tried to beat off the insects, but the thousands of vermin crawled over them and bit and stung them until both dropped down nearly dead. Kana′tĭ stood looking on until he thought they had been punished enough, when he knocked off the vermin and made the boys a talk. “Now, you rascals,” said he, “you have always had plenty to eat and never had to work for it. Whenever you were hungry all I had to do was to come up here and get a deer or a turkey and bring it home for your mother to cook; but now you have let out all the animals, and after this when you want a deer to eat you will have to hunt all over the woods for it, and then maybe not find one. Go home now to your mother, while I see if I can find something to eat for supper.”

When the boys got home again they were very tired and hungry and asked their mother for something to eat. “There is no meat,” said Selu, “but wait a little while and I’ll get you something.” So she took a basket and started out to the storehouse. This storehouse was built upon poles high up from the ground, to keep it out of the reach of animals, and there was a ladder to climb up by, and one door, but no other opening. Every day when Selu got ready to cook the dinner she would go out to the storehouse with a basket and bring it back full of corn and beans. The boys had never been inside the storehouse, so wondered where all the corn and beans could come from, as the house was not a very large one; so as soon as Selu went out of the door the Wild Boy said to his brother, “Let’s go and see what she does.” They ran around and climbed up at the back of the storehouse and pulled out a piece of clay from between the logs, so that they could look in. There they saw Selu standing in the middle of the room with the basket in front of her on the floor. Leaning over the basket, she rubbed her stomach—so—and the basket was half full of corn. Then she rubbed under her armpits—so—and the basket was full to the top with beans. The boys looked at each other and said, “This will never do; our mother is a witch. If we eat any of that it will poison us. We must kill her.”

When the boys came back into the house, she knew their thoughts before they spoke. “So you are going to kill me?” said Selu. “Yes,” said the boys, “you are a witch.” “Well,” said their mother, “when you have killed me, clear a large piece of ground in front of the house and drag my body seven times around the circle. Then drag me seven times over the ground inside the circle, and stay up all night and watch, and in the morning you will have plenty of corn.” The boys killed her with their clubs, and cut off her head and put it up on the roof of the house with her face turned to the west, and told her to look for her husband. Then they set to work to clear the ground in front of the [245]house, but instead of clearing the whole piece they cleared only seven little spots. This is why corn now grows only in a few places instead of over the whole world. They dragged the body of Selu around the circle, and wherever her blood fell on the ground the corn sprang up. But instead of dragging her body seven times across the ground they dragged it over only twice, which is the reason the Indians still work their crop but twice. The two brothers sat up and watched their corn all night, and in the morning it was full grown and ripe.

When Kana′tĭ came home at last, he looked around, but could not see Selu anywhere, and asked the boys where was their mother. “She was a witch, and we killed her,” said the boys; “there is her head up there on top of the house.” When he saw his wife’s head on the roof, he was very angry, and said, “I won’t stay with you any longer; I am going to the Wolf people.” So he started off, but before he had gone far the Wild Boy changed himself again to a tuft of down, which fell on Kana′tĭ’s shoulder. When Kana′tĭ reached the settlement of the Wolf people, they were holding a council in the townhouse. He went in and sat down with the tuft of bird’s down on his shoulder, but he never noticed it. When the Wolf chief asked him his business, he said: “I have two bad boys at home, and I want you to go in seven days from now and play ball against them.” Although Kana′tĭ spoke as though he wanted them to play a game of ball, the Wolves knew that he meant for them to go and kill the two boys. They promised to go. Then the bird’s down blew off from Kana′tĭ’s shoulder, and the smoke carried it up through the hole in the roof of the townhouse. When it came down on the ground outside, the Wild Boy took his right shape again and went home and told his brother all that he had heard in the townhouse. But when Kana′tĭ left the Wolf people he did not return home, but went on farther.

The boys then began to get ready for the Wolves, and the Wild Boy—the magician—told his brother what to do. They ran around the house in a wide circle until they had made a trail all around it excepting on the side from which the Wolves would come, where they left a small open space. Then they made four large bundles of arrows and placed them at four different points on the outside of the circle, after which they hid themselves in the woods and waited for the Wolves. In a day or two a whole party of Wolves came and surrounded the house to kill the boys. The Wolves did not notice the trail around the house, because they came in where the boys had left the opening, but the moment they went inside the circle the trail changed to a high brush fence and shut them in. Then the boys on the outside took their arrows and began shooting them down, and as the Wolves could not jump over the fence they were all killed, excepting a few that escaped through the opening into a great swamp close by. The boys ran around the swamp, and a circle of fire sprang up in their [246]tracks and set fire to the grass and bushes and burned up nearly all the other Wolves. Only two or three got away, and from these have come all the wolves that are now in the world.

Soon afterward some strangers from a distance, who had heard that the brothers had a wonderful grain from which they made bread, came to ask for some, for none but Selu and her family had ever known corn before. The boys gave them seven grains of corn, which they told them to plant the next night on their way home, sitting up all night to watch the corn, which would have seven ripe ears in the morning. These they were to plant the next night and watch in the same way, and so on every night until they reached home, when they would have corn enough to supply the whole people. The strangers lived seven days’ journey away. They took the seven grains and watched all through the darkness until morning, when they saw seven tall stalks, each stalk bearing a ripened ear. They gathered the ears and went on their way. The next night they planted all their corn, and guarded it as before until daybreak, when they found an abundant increase. But the way was long and the sun was hot, and the people grew tired. On the last night before reaching home they fell asleep, and in the morning the corn they had planted had not even sprouted. They brought with them to their settlement what corn they had left and planted it, and with care and attention were able to raise a crop. But ever since the corn must be watched and tended through half the year, which before would grow and ripen in a night.

As Kana′tĭ did not return, the boys at last concluded to go and find him. The Wild Boy took a gaming wheel and rolled it toward the Darkening land. In a little while the wheel came rolling back, and the boys knew their father was not there. He rolled it to the south and to the north, and each time the wheel came back to him, and they knew their father was not there. Then he rolled it toward the Sunland, and it did not return. “Our father is there,” said the Wild Boy, “let us go and find him.” So the two brothers set off toward the east, and after traveling a long time they came upon Kana′tĭ walking along with a little dog by his side. “You bad boys,” said their father, “have you come here?” “Yes,” they answered, “we always accomplish what we start out to do—we are men.” “This dog overtook me four days ago,” then said Kana′tĭ, but the boys knew that the dog was the wheel which they had sent after him to find him. “Well,” said Kana′tĭ, “as you have found me, we may as well travel together, but I shall take the lead.”

Soon they came to a swamp, and Kana′tĭ told them there was something dangerous there and they must keep away from it. He went on ahead, but as soon as he was out of sight the Wild Boy said to his brother, “Come and let us see what is in the swamp.” They went in together, and in the middle of the swamp they found a large [247]panther asleep. The Wild Boy got out an arrow and shot the panther in the side of the head. The panther turned his head and the other boy shot him on that side. He turned his head away again and the two brothers shot together—tust, tust, tust! But the panther was not hurt by the arrows and paid no more attention to the boys. They came out of the swamp and soon overtook Kana′tĭ, waiting for them. “Did you find it?” asked Kana′tĭ. “Yes,” said the boys, “we found it, but it never hurt us. We are men.” Kana′tĭ was surprised, but said nothing, and they went on again.

After a while he turned to them and said, “Now you must be careful. We are coming to a tribe called the Anăda′dûñtăskĭ (“Roasters,” i. e., cannibals), and if they get you they will put you into a pot and feast on you.” Then he went on ahead. Soon the boys came to a tree which had been struck by lightning, and the Wild Boy directed his brother to gather some of the splinters from the tree and told him what to do with them. In a little while they came to the settlement of the cannibals, who, as soon as they saw the boys, came running out, crying, “Good, here are two nice fat strangers. Now we’ll have a grand feast!” They caught the boys and dragged them into the townhouse, and sent word to all the people of the settlement to come to the feast. They made up a great fire, put water into a large pot and set it to boiling, and then seized the Wild Boy and put him down into it. His brother was not in the least frightened and made no attempt to escape, but quietly knelt down and began putting the splinters into the fire, as if to make it burn better. When the cannibals thought the meat was about ready they lifted the pot from the fire, and that instant a blinding light filled the townhouse, and the lightning began to dart from one side to the other, striking down the cannibals until not one of them was left alive. Then the lightning went up through the smoke-hole, and the next moment there were the two boys standing outside the townhouse as though nothing had happened. They went on and soon met Kana′tĭ, who seemed much surprised to see them, and said, “What! are you here again?” “O, yes, we never give up. We are great men!” “What did the cannibals do to you?” “We met them and they brought us to their townhouse, but they never hurt us.” Kana′tĭ said nothing more, and they went on.

* * *

He soon got out of sight of the boys, but they kept on until they came to the end of the world, where the sun comes out. The sky was just coming down when they got there, but they waited until it went up again, and then they went through and climbed up on the other side. There they found Kana′tĭ and Selu sitting together. The old folk received them kindly and were glad to see them, telling them they might stay there a while, but then they must go to live where the sun goes down. The boys stayed with their parents seven days and [248]then went on toward the Darkening land, where they are now. We call them Anisga′ya Tsunsdi′ (The Little Men), and when they talk to each other we hear low rolling thunder in the west.

After Kana′tĭ’s boys had let the deer out from the cave where their father used to keep them, the hunters tramped about in the woods for a long time without finding any game, so that the people were very hungry. At last they heard that the Thunder Boys were now living in the far west, beyond the sun door, and that if they were sent for they could bring back the game. So they sent messengers for them, and the boys came and sat down in the middle of the townhouse and began to sing.

At the first song there was a roaring sound like a strong wind in the northwest, and it grew louder and nearer as the boys sang on, until at the seventh song a whole herd of deer, led by a large buck, came out from the woods. The boys had told the people to be ready with their bows and arrows, and when the song was ended and all the deer were close around the townhouse, the hunters shot into them and killed as many as they needed before the herd could get back into the timber.

Then the Thunder Boys went back to the Darkening land, but before they left they taught the people the seven songs with which to call up the deer. It all happened so long ago that the songs are now forgotten—all but two, which the hunters still sing whenever they go after deer.

WAHNENAUHI VERSION

After the world had been brought up from under the water, “They then made a man and a woman and led them around the edge of the island. On arriving at the starting place they planted some corn, and then told the man and woman to go around the way they had been led. This they did, and on returning they found the corn up and growing nicely. They were then told to continue the circuit. Each trip consumed more time. At last the corn was ripe and ready for use.”

Another story is told of how sin came into the world. A man and a woman reared a large family of children in comfort and plenty, with very little trouble about providing food for them. Every morning the father went forth and very soon returned bringing with him a deer, or a turkey, or some other animal or fowl. At the same time the mother went out and soon returned with a large basket filled with ears of corn which she shelled and pounded in a mortar, thus making meal for bread.

When the children grew up, seeing with what apparent ease food was provided for them, they talked to each other about it, wondering that they never saw such things as their parents brought in. At last [249]one proposed to watch when their parents went out and to follow them.

Accordingly next morning the plan was carried out. Those who followed the father saw him stop at a short distance from the cabin and turn over a large stone that appeared to be carelessly leaned against another. On looking closely they saw an entrance to a large cave, and in it were many different kinds of animals and birds, such as their father had sometimes brought in for food. The man standing at the entrance called a deer, which was lying at some distance and back of some other animals. It rose immediately as it heard the call and came close up to him. He picked it up, closed the mouth of the cave, and returned, not once seeming to suspect what his sons had done.

When the old man was fairly out of sight, his sons, rejoicing how they had outwitted him, left their hiding place and went to the cave, saying they would show the old folks that they, too, could bring in something. They moved the stone away, though it was very heavy and they were obliged to use all their united strength. When the cave was opened, the animals, instead of waiting to be picked up, all made a rush for the entrance, and leaping past the frightened and bewildered boys, scattered in all directions and disappeared in the wilderness, while the guilty offenders could do nothing but gaze in stupefied amazement as they saw them escape. There were animals of all kinds, large and small—buffalo, deer, elk, antelope, raccoons, and squirrels; even catamounts and panthers, wolves and foxes, and many others, all fleeing together. At the same time birds of every kind were seen emerging from the opening, all in the same wild confusion as the quadrupeds—turkeys, geese, swans, ducks, quails, eagles, hawks, and owls.

Those who followed the mother saw her enter a small cabin, which they had never seen before, and close the door. The culprits found a small crack through which they could peer. They saw the woman place a basket on the ground and standing over it shake herself vigorously, jumping up and down, when lo and behold! large ears of corn began to fall into the basket. When it was well filled she took it up and, placing it on her head, came out, fastened the door, and prepared their breakfast as usual. When the meal had been finished in silence the man spoke to his children, telling them that he was aware of what they had done; that now he must die and they would be obliged to provide for themselves. He made bows and arrows for them, then sent them to hunt for the animals which they had turned loose.

Then the mother told them that as they had found out her secret she could do nothing more for them; that she would die, and they must drag her body around over the ground; that wherever her body was dragged corn would come up. Of this they were to make their bread. She told them that they must always save some for seed and plant every year.[250]

4. ORIGIN OF DISEASE AND MEDICINE

In the old days the beasts, birds, fishes, insects, and plants could all talk, and they and the people lived together in peace and friendship. But as time went on the people increased so rapidly that their settlements spread over the whole earth, and the poor animals found themselves beginning to be cramped for room. This was bad enough, but to make it worse Man invented bows, knives, blowguns, spears, and hooks, and began to slaughter the larger animals, birds, and fishes for their flesh or their skins, while the smaller creatures, such as the frogs and worms, were crushed and trodden upon without thought, out of pure carelessness or contempt. So the animals resolved to consult upon measures for their common safety.

The Bears were the first to meet in council in their townhouse under Kuwâ′hĭ mountain, the “Mulberry place,” and the old White Bear chief presided. After each in turn had complained of the way in which Man killed their friends, ate their flesh, and used their skins for his own purposes, it was decided to begin war at once against him. Some one asked what weapons Man used to destroy them. “Bows and arrows, of course,” cried all the Bears in chorus. “And what are they made of?” was the next question. “The bow of wood, and the string of our entrails,” replied one of the Bears. It was then proposed that they make a bow and some arrows and see if they could not use the same weapons against Man himself. So one Bear got a nice piece of locust wood and another sacrificed himself for the good of the rest in order to furnish a piece of his entrails for the string. But when everything was ready and the first Bear stepped up to make the trial, it was found that in letting the arrow fly after drawing back the bow, his long claws caught the string and spoiled the shot. This was annoying, but some one suggested that they might trim his claws, which was accordingly done, and on a second trial it was found that the arrow went straight to the mark. But here the chief, the old White Bear, objected, saying it was necessary that they should have long claws in order to be able to climb trees. “One of us has already died to furnish the bow-string, and if we now cut off our claws we must all starve together. It is better to trust to the teeth and claws that nature gave us, for it is plain that man’s weapons were not intended for us.”

No one could think of any better plan, so the old chief dismissed the council and the Bears dispersed to the woods and thickets without having concerted any way to prevent the increase of the human race. Had the result of the council been otherwise, we should now be at war with the Bears, but as it is, the hunter does not even ask the Bear’s pardon when he kills one.

The Deer next held a council under their chief, the Little Deer, and after some talk decided to send rheumatism to every hunter who should [251]kill one of them unless he took care to ask their pardon for the offense. They sent notice of their decision to the nearest settlement of Indians and told them at the same time what to do when necessity forced them to kill one of the Deer tribe. Now, whenever the hunter shoots a Deer, the Little Deer, who is swift as the wind and can not be wounded, runs quickly up to the spot and, bending over the blood-stains, asks the spirit of the Deer if it has heard the prayer of the hunter for pardon. If the reply be “Yes,” all is well, and the Little Deer goes on his way; but if the reply be “No,” he follows on the trail of the hunter, guided by the drops of blood on the ground, until he arrives at his cabin in the settlement, when the Little Deer enters invisibly and strikes the hunter with rheumatism, so that he becomes at once a helpless cripple. No hunter who has regard for his health ever fails to ask pardon of the Deer for killing it, although some hunters who have not learned the prayer may try to turn aside the Little Deer from his pursuit by building a fire behind them in the trail.

Next came the Fishes and Reptiles, who had their own complaints against Man. They held their council together and determined to make their victims dream of snakes twining about them in slimy folds and blowing foul breath in their faces, or to make them dream of eating raw or decaying fish, so that they would lose appetite, sicken, and die. This is why people dream about snakes and fish.

Finally the Birds, Insects, and smaller animals came together for the same purpose, and the Grubworm was chief of the council. It was decided that each in turn should give an opinion, and then they would vote on the question as to whether or not Man was guilty. Seven votes should be enough to condemn him. One after another denounced Man’s cruelty and injustice toward the other animals and voted in favor of his death. The Frog spoke first, saying: “We must do something to check the increase of the race, or people will become so numerous that we shall be crowded from off the earth. See how they have kicked me about because I’m ugly, as they say, until my back is covered with sores;” and here he showed the spots on his skin. Next came the Bird—no one remembers now which one it was—who condemned Man “because he burns my feet off,” meaning the way in which the hunter barbecues birds by impaling them on a stick set over the fire, so that their feathers and tender feet are singed off. Others followed in the same strain. The Ground-squirrel alone ventured to say a good word for Man, who seldom hurt him because he was so small, but this made the others so angry that they fell upon the Ground-squirrel and tore him with their claws, and the stripes are on his back to this day.

They began then to devise and name so many new diseases, one after another, that had not their invention at last failed them, no one of the human race would have been able to survive. The Grubworm grew [252]constantly more pleased as the name of each disease was called off, until at last they reached the end of the list, when some one proposed to make menstruation sometimes fatal to women. On this he rose up in his place and cried: “Wadâñ′! [Thanks!] I’m glad some more of them will die, for they are getting so thick that they tread on me.” The thought fairly made him shake with joy, so that he fell over backward and could not get on his feet again, but had to wriggle off on his back, as the Grubworm has done ever since.

When the Plants, who were friendly to Man, heard what had been done by the animals, they determined to defeat the latters’ evil designs. Each Tree, Shrub, and Herb, down even to the Grasses and Mosses, agreed to furnish a cure for some one of the diseases named, and each said: “I shall appear to help Man when he calls upon me in his need.” Thus came medicine; and the plants, every one of which has its use if we only knew it, furnish the remedy to counteract the evil wrought by the revengeful animals. Even weeds were made for some good purpose, which we must find out for ourselves. When the doctor does not know what medicine to use for a sick man the spirit of the plant tells him.

5. THE DAUGHTER OF THE SUN

The Sun lived on the other side of the sky vault, but her daughter lived in the middle of the sky, directly above the earth, and every day as the Sun was climbing along the sky arch to the west she used to stop at her daughter’s house for dinner.

Now, the Sun hated the people on the earth, because they could never look straight at her without screwing up their faces. She said to her brother, the Moon, “My grandchildren are ugly; they grin all over their faces when they look at me.” But the Moon said, “I like my younger brothers; I think they are very handsome”—because they always smiled pleasantly when they saw him in the sky at night, for his rays were milder.

The Sun was jealous and planned to kill all the people, so every day when she got near her daughter’s house she sent down such sultry rays that there was a great fever and the people died by hundreds, until everyone had lost some friend and there was fear that no one would be left. They went for help to the Little Men, who said the only way to save themselves was to kill the Sun.

The Little Men made medicine and changed two men to snakes, the Spreading-adder and the Copperhead, and sent them to watch near the door of the daughter of the Sun to bite the old Sun when she came next day. They went together and hid near the house until the Sun came, but when the Spreading-adder was about to spring, the bright light blinded him and he could only spit out yellow slime, as he does to this day when he tries to bite. She called him a nasty thing and [253]went by into the house, and the Copperhead crawled off without trying to do anything.

So the people still died from the heat, and they went to the Little Men a second time for help. The Little Men made medicine again and changed one man into the great Uktena and another into the Rattlesnake and sent them to watch near the house and kill the old Sun when she came for dinner. They made the Uktena very large, with horns on his head, and everyone thought he would be sure to do the work, but the Rattlesnake was so quick and eager that he got ahead and coiled up just outside the house, and when the Sun’s daughter opened the door to look out for her mother, he sprang up and bit her and she fell dead in the doorway. He forgot to wait for the old Sun, but went back to the people, and the Uktena was so very angry that he went back, too. Since then we pray to the rattlesnake and do not kill him, because he is kind and never tries to bite if we do not disturb him. The Uktena grew angrier all the time and very dangerous, so that if he even looked at a man, that man’s family would die. After a long time the people held a council and decided that he was too dangerous to be with them, so they sent him up to Gălûñ′lătĭ, and he is there now. The Spreading-adder, the Copperhead, the Rattlesnake, and the Uktena were all men.

When the Sun found her daughter dead, she went into the house and grieved, and the people did not die any more, but now the world was dark all the time, because the Sun would not come out. They went again to the Little Men, and these told them that if they wanted the Sun to come out again they must bring back her daughter from Tsûsginâ′ĭ, the Ghost country, in Usûñhi′yĭ, the Darkening land in the west. They chose seven men to go, and gave each a sourwood rod a hand-breadth long. The Little Men told them they must take a box with them, and when they got to Tsûsginâ′ĭ they would find all the ghosts at a dance. They must stand outside the circle, and when the young woman passed in the dance they must strike her with the rods and she would fall to the ground. Then they must put her into the box and bring her back to her mother, but they must be very sure not to open the box, even a little way, until they were home again.

They took the rods and a box and traveled seven days to the west until they came to the Darkening land. There were a great many people there, and they were having a dance just as if they were at home in the settlements. The young woman was in the outside circle, and as she swung around to where the seven men were standing, one struck her with his rod and she turned her head and saw him. As she came around the second time another touched her with his rod, and then another and another, until at the seventh round she fell out of the ring, and they put her into the box and closed the lid fast. The other ghosts seemed never to notice what had happened.[254]

They took up the box and started home toward the east. In a little while the girl came to life again and begged to be let out of the box, but they made no answer and went on. Soon she called again and said she was hungry, but still they made no answer and went on. After another while she spoke again and called for a drink and pleaded so that it was very hard to listen to her, but the men who carried the box said nothing and still went on. When at last they were very near home, she called again and begged them to raise the lid just a little, because she was smothering. They were afraid she was really dying now, so they lifted the lid a little to give her air, but as they did so there was a fluttering sound inside and something flew past them into the thicket and they heard a redbird cry, “kwish! kwish! kwish!” in the bushes. They shut down the lid and went on again to the settlements, but when they got there and opened the box it was empty.

So we know the Redbird is the daughter of the Sun, and if the men had kept the box closed, as the Little Men told them to do, they would have brought her home safely, and we could bring back our other friends also from the Ghost country, but now when they die we can never bring them back.

The Sun had been glad when they started to the Ghost country, but when they came back without her daughter she grieved and cried, “My daughter, my daughter,” and wept until her tears made a flood upon the earth, and the people were afraid the world would be drowned. They held another council, and sent their handsomest young men and women to amuse her so that she would stop crying. They danced before the Sun and sang their best songs, but for a long time she kept her face covered and paid no attention, until at last the drummer suddenly changed the song, when she lifted up her face, and was so pleased at the sight that she forgot her grief and smiled.

6. HOW THEY BROUGHT BACK THE TOBACCO

In the beginning of the world, when people and animals were all the same, there was only one tobacco plant, to which they all came for their tobacco until the Dagûlʻkû geese stole it and carried it far away to the south. The people were suffering without it, and there was one old woman who grew so thin and weak that everybody said she would soon die unless she could get tobacco to keep her alive.

Different animals offered to go for it, one after another, the larger ones first and then the smaller ones, but the Dagûlʻkû saw and killed every one before he could get to the plant. After the others the little Mole tried to reach it by going under the ground, but the Dagûlʻkû saw his track and killed him as he came out.

At last the Hummingbird offered, but the others said he was entirely too small and might as well stay at home. He begged them to let him try, so they showed him a plant in a field and told him to let them see [255]how he would go about it. The next moment he was gone and they saw him sitting on the plant, and then in a moment he was back again, but no one had seen him going or coming, because he was so swift. “This is the way I’ll do,” said the Hummingbird, so they let him try.

He flew off to the east, and when he came in sight of the tobacco the Dagûlʻkû were watching all about it, but they could not see him because he was so small and flew so swiftly. He darted down on the plant—tsa!—and snatched off the top with the leaves and seeds, and was off again before the Dagûlʻkû knew what had happened. Before he got home with the tobacco the old woman had fainted and they thought she was dead, but he blew the smoke into her nostrils, and with a cry of “Tsâ′lû! [Tobacco!]” she opened her eyes and was alive again.

SECOND VERSION

The people had tobacco in the beginning, but they had used it all, and there was great suffering for want of it. There was one old man so old that he had to be kept alive by smoking, and as his son did not want to see him die he decided to go himself to try and get some more. The tobacco country was far in the south, with high mountains all around it, and the passes were guarded, so that it was very hard to get into it, but the young man was a conjurer and was not afraid. He traveled southward until he came to the mountains on the border of the tobacco country. Then he opened his medicine bag and took out a hummingbird skin and put it over himself like a dress. Now he was a hummingbird and flew over the mountains to the tobacco field and pulled some of the leaves and seed and put them into his medicine bag. He was so small and swift that the guards, whoever they were, did not see him, and when he had taken as much as he could carry he flew back over the mountains in the same way. Then he took off the hummingbird skin and put it into his medicine bag, and was a man again. He started home, and on his way came to a tree that had a hole in the trunk, like a door, near the first branches, and a very pretty woman was looking out from it. He stopped and tried to climb the tree, but although he was a good climber he found that he always slipped back. He put on a pair of medicine moccasins from his pouch, and then he could climb the tree, but when he reached the first branches he looked up and the hole was still as far away as before. He climbed higher and higher, but every time he looked up the hole seemed to be farther than before, until at last he was tired and came down again. When he reached home he found his father very weak, but still alive, and one draw at the pipe made him strong again. The people planted the seed and have had tobacco ever since.

7. THE JOURNEY TO THE SUNRISE

A long time ago several young men made up their minds to find the place where the Sun lives and see what the Sun is like. They got [256]ready their bows and arrows, their parched corn and extra moccasins, and started out toward the east. At first they met tribes they knew, then they came to tribes they had only heard about, and at last to others of which they had never heard.

There was a tribe of root eaters and another of acorn eaters, with great piles of acorn shells near their houses. In one tribe they found a sick man dying, and were told it was the custom there when a man died to bury his wife in the same grave with him. They waited until he was dead, when they saw his friends lower the body into a great pit, so deep and dark that from the top they could not see the bottom. Then a rope was tied around the woman’s body, together with a bundle of pine knots, a lighted pine knot was put into her hand, and she was lowered into the pit to die there in the darkness after the last pine knot was burned.

The young men traveled on until they came at last to the sunrise place where the sky reaches down to the ground. They found that the sky was an arch or vault of solid rock hung above the earth and was always swinging up and down, so that when it went up there was an open place like a door between the sky and ground, and when it swung back the door was shut. The Sun came out of this door from the east and climbed along on the inside of the arch. It had a human figure, but was too bright for them to see clearly and too hot to come very near. They waited until the Sun had come out and then tried to get through while the door was still open, but just as the first one was in the doorway the rock came down and crushed him. The other six were afraid to try it, and as they were now at the end of the world they turned around and started back again, but they had traveled so far that they were old men when they reached home.

8. THE MOON AND THE THUNDERS.

The Sun was a young woman and lived in the East, while her brother, the Moon, lived in the West. The girl had a lover who used to come every month in the dark of the moon to court her. He would come at night, and leave before daylight, and although she talked with him she could not see his face in the dark, and he would not tell her his name, until she was wondering all the time who it could be. At last she hit upon a plan to find out, so the next time he came, as they were sitting together in the dark of the âsĭ, she slyly dipped her hand into the cinders and ashes of the fireplace and rubbed it over his face, saying, “Your face is cold; you must have suffered from the wind,” and pretending to be very sorry for him, but he did not know that she had ashes on her hand. After a while he left her and went away again.

The next night when the Moon came up in the sky his face was covered with spots, and then his sister knew he was the one who had been [257]coming to see her. He was so much ashamed to have her know it that he kept as far away as he could at the other end of the sky all the night. Ever since he tries to keep a long way behind the Sun, and when he does sometimes have to come near her in the west he makes himself as thin as a ribbon so that he can hardly be seen.

Some old people say that the moon is a ball which was thrown up against the sky in a game a long time ago. They say that two towns were playing against each other, but one of them had the best runners and had almost won the game, when the leader of the other side picked up the ball with his hand—a thing that is not allowed in the game—and tried to throw it to the goal, but it struck against the solid sky vault and was fastened there, to remind players never to cheat. When the moon looks small and pale it is because some one has handled the ball unfairly, and for this reason they formerly played only at the time of a full moon.

When the sun or moon is eclipsed it is because a great frog up in the sky is trying to swallow it. Everybody knows this, even the Creeks and the other tribes, and in the olden times, eighty or a hundred years ago, before the great medicine men were all dead, whenever they saw the sun grow dark the people would come together and fire guns and beat the drum, and in a little while this would frighten off the great frog and the sun would be all right again.

The common people call both Sun and Moon Nûñdă, one being “Nûñdă that dwells in the day” and the other “Nûñdă that dwells in the night,” but the priests call the Sun Su′tălidihĭ′, “Six-killer,” and the Moon Ge′ʻyăgu′ga, though nobody knows now what this word means, or why they use these names. Sometimes people ask the Moon not to let it rain or snow.

The great Thunder and his sons, the two Thunder boys, live far in the west above the sky vault. The lightning and the rainbow are their beautiful dress. The priests pray to the Thunder and call him the Red Man, because that is the brightest color of his dress. There are other Thunders that live lower down, in the cliffs and mountains, and under waterfalls, and travel on invisible bridges from one high peak to another where they have their town houses. The great Thunders above the sky are kind and helpful when we pray to them, but these others are always plotting mischief. One must not point at the rainbow, or one’s finger will swell at the lower joint.

9. WHAT THE STARS ARE LIKE

There are different opinions about the stars. Some say they are balls of light, others say they are human, but most people say they are living creatures covered with luminous fur or feathers.

One night a hunting party camping in the mountains noticed two lights like large stars moving along the top of a distant ridge. They [258]wondered and watched until the light disappeared on the other side. The next night, and the next, they saw the lights again moving along the ridge, and after talking over the matter decided to go on the morrow and try to learn the cause. In the morning they started out and went until they came to the ridge, where, after searching some time, they found two strange creatures about so large (making a circle with outstretched arms), with round bodies covered with fine fur or downy feathers, from which small heads stuck out like the heads of terrapins. As the breeze played upon these feathers showers of sparks flew out.

The hunters carried the strange creatures back to the camp, intending to take them home to the settlements on their return. They kept them several days and noticed that every night they would grow bright and shine like great stars, although by day they were only balls of gray fur, except when the wind stirred and made the sparks fly out. They kept very quiet, and no one thought of their trying to escape, when, on the seventh night, they suddenly rose from the ground like balls of fire and were soon above the tops of the trees. Higher and higher they went, while the wondering hunters watched, until at last they were only two bright points of light in the dark sky, and then the hunters knew that they were stars.

10. ORIGIN OF THE PLEIADES AND THE PINE

Long ago, when the world was new, there were seven boys who used to spend all their time down by the townhouse playing the gatayû′stĭ game, rolling a stone wheel along the ground and sliding a curved stick after it to strike it. Their mothers scolded, but it did no good, so one day they collected some gatayû′stĭ stones and boiled them in the pot with the corn for dinner. When the boys came home hungry their mothers dipped out the stones and said, “Since you like the gatayû′stĭ better than the cornfield, take the stones now for your dinner.”

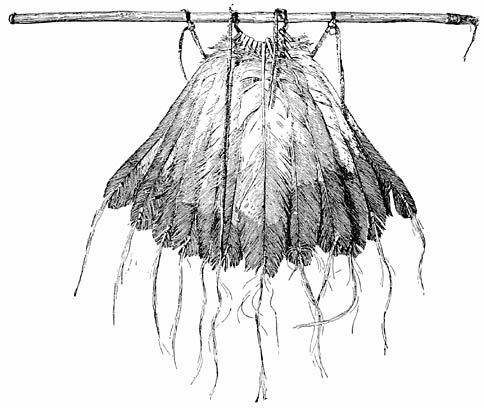

The boys were very angry, and went down to the townhouse, saying, “As our mothers treat us this way, let us go where we shall never trouble them any more.” They began a dance—some say it was the Feather dance—and went round and round the townhouse, praying to the spirits to help them. At last their mothers were afraid something was wrong and went out to look for them. They saw the boys still dancing around the townhouse, and as they watched they noticed that their feet were off the earth, and that with every round they rose higher and higher in the air. They ran to get their children, but it was too late, for they were already above the roof of the townhouse—all but one, whose mother managed to pull him down with the gatayû′stĭ pole, but he struck the ground with such force that he sank into it and the earth closed over him.

The other six circled higher and higher until they went up to the [259]sky, where we see them now as the Pleiades, which the Cherokee still call Ani′tsutsă (The Boys). The people grieved long after them, but the mother whose boy had gone into the ground came every morning and every evening to cry over the spot until the earth was damp with her tears. At last a little green shoot sprouted up and grew day by day until it became the tall tree that we call now the pine, and the pine is of the same nature as the stars and holds in itself the same bright light.

11. THE MILKY WAY

Some people in the south had a corn mill, in which they pounded the corn into meal, and several mornings when they came to fill it they noticed that some of the meal had been stolen during the night. They examined the ground and found the tracks of a dog, so the next night they watched, and when the dog came from the north and began to eat the meal out of the bowl they sprang out and whipped him. He ran off howling to his home in the north, with the meal dropping from his mouth as he ran, and leaving behind a white trail where now we see the Milky Way, which the Cherokee call to this day Giʻlĭ′-utsûñ′stănûñ′yĭ, “Where the dog ran.”

12. ORIGIN OF STRAWBERRIES

When the first man was created and a mate was given to him, they lived together very happily for a time, but then began to quarrel, until at last the woman left her husband and started off toward Nûñdâgûñ′yĭ, the Sun land, in the east. The man followed alone and grieving, but the woman kept on steadily ahead and never looked behind, until Une′ʻlănûñ′hĭ, the great Apportioner (the Sun), took pity on him and asked him if he was still angry with his wife. He said he was not, and Une′ʻlănûñ′hĭ then asked him if he would like to have her back again, to which he eagerly answered yes.

So Une′ʻlănûñ′hĭ caused a patch of the finest ripe huckleberries to spring up along the path in front of the woman, but she passed by without paying any attention to them. Farther on he put a clump of blackberries, but these also she refused to notice. Other fruits, one, two, and three, and then some trees covered with beautiful red service berries, were placed beside the path to tempt her, but she still went on until suddenly she saw in front a patch of large ripe strawberries, the first ever known. She stooped to gather a few to eat, and as she picked them she chanced to turn her face to the west, and at once the memory of her husband came back to her and she found herself unable to go on. She sat down, but the longer she waited the stronger became her desire for her husband, and at last she gathered a bunch of the finest berries and started back along the path to give them to him. He met her kindly and they went home together.[260]

13. THE GREAT YELLOW-JACKET: ORIGIN OF FISH AND FROGS

A long time ago the people of the old town of Kanu′gaʻlâ′yĭ (“Brier place,” or Briertown), on Nantahala river, in the present Macon county, North Carolina, were much annoyed by a great insect called U′laʻgû′, as large as a house, which used to come from some secret hiding place, and darting swiftly through the air, would snap up children from their play and carry them away. It was unlike any other insect ever known, and the people tried many times to track it to its home, but it was too swift to be followed.

They killed a squirrel and tied a white string to it, so that its course could be followed with the eye, as bee hunters follow the flight of a bee to its tree. The U′laʻgû′ came and carried off the squirrel with the string hanging to it, but darted away so swiftly through the air that it was out of sight in a moment. They killed a turkey and put a longer white string to it, and the U′laʻgû′ came and took the turkey, but was gone again before they could see in what direction it flew. They took a deer ham and tied a white string to it, and again the U′laʻgû′ swooped down and bore it off so swiftly that it could not be followed. At last they killed a yearling deer and tied a very long white string to it. The U′laʻgû′ came again and seized the deer, but this time the load was so heavy that it had to fly slowly and so low down that the string could be plainly seen.

The hunters got together for the pursuit. They followed it along a ridge to the east until they came near where Franklin now is, when, on looking across the valley to the other side, they saw the nest of the U′laʻgû′ in a large cave in the rocks. On this they raised a great shout and made their way rapidly down the mountain and across to the cave. The nest had the entrance below with tiers of cells built up one above another to the roof of the cave. The great U′laʻgû′ was there, with thousands of smaller ones, that we now call yellow-jackets. The hunters built fires around the hole, so that the smoke filled the cave and smothered the great insect and multitudes of the smaller ones, but others which were outside the cave were not killed, and these escaped and increased until now the yellow-jackets, which before were unknown, are all over the world. The people called the cave Tsgâgûñ′yĭ, “Where the yellow-jacket was,” and the place from which they first saw the nest they called Aʻtahi′ta, “Where they shouted,” and these are their names today.

They say also that all the fish and frogs came from a great monster fish and frog which did much damage until at last they were killed by the people, who cut them up into little pieces which were thrown into the water and afterward took shape as the smaller fishes and frogs.[261]

14. THE DELUGE

A long time ago a man had a dog, which began to go down to the river every day and look at the water and howl. At last the man was angry and scolded the dog, which then spoke to him and said: “Very soon there is going to be a great freshet and the water will come so high that everybody will be drowned; but if you will make a raft to get upon when the rain comes you can be saved, but you must first throw me into the water.” The man did not believe it, and the dog said, “If you want a sign that I speak the truth, look at the back of my neck.” He looked and saw that the dog’s neck had the skin worn off so that the bones stuck out.

Then he believed the dog, and began to build a raft. Soon the rain came and he took his family, with plenty of provisions, and they all got upon it. It rained for a long time, and the water rose until the mountains were covered and all the people in the world were drowned. Then the rain stopped and the waters went down again, until at last it was safe to come off the raft. Now there was no one alive but the man and his family, but one day they heard a sound of dancing and shouting on the other side of the ridge. The man climbed to the top and looked over; everything was still, but all along the valley he saw great piles of bones of the people who had been drowned, and then he knew that the ghosts had been dancing.

[Contents]

Quadruped Myths

15. THE FOURFOOTED TRIBES

In Cherokee mythology, as in that of Indian tribes generally, there is no essential difference between men and animals. In the primal genesis period they seem to be completely undifferentiated, and we find all creatures alike living and working together in harmony and mutual helpfulness until man, by his aggressiveness and disregard for the rights of the others, provokes their hostility, when insects, birds, fishes, reptiles, and fourfooted beasts join forces against him (see story, “Origin of Disease and Medicine”). Henceforth their lives are apart, but the difference is always one of degree only. The animals, like the people, are organized into tribes and have like them their chiefs and townhouses, their councils and ballplays, and the same hereafter in the Darkening land of Usûñhi′yĭ. Man is still the paramount power, and hunts and slaughters the others as his own necessities compel, but is obliged to satisfy the animal tribes in every instance, very much as a murder is compounded for, according to the Indian system, by “covering the bones of the dead” with presents for the bereaved relatives.

This pardon to the hunter is made the easier through a peculiar [262]doctrine of reincarnation, according to which, as explained by the shamans, there is assigned to every animal a definite life term which can not be curtailed by violent means. If it is killed before the expiration of the allotted time the death is only temporary and the body is immediately resurrected in its proper shape from the blood drops, and the animal continues its existence until the end of the predestined period, when the body is finally dissolved and the liberated spirit goes to join its kindred shades in the Darkening land. This idea appears in the story of the bear man and in the belief concerning the Little Deer. Death is thus but a temporary accident and the killing a mere minor crime. By some priests it is held that there are seven successive reanimations before the final end.