When I was a child, kids would come to school with sprigs of mistletoe that they had harvested from trees. Even when I was very young, I would allow the mistletoe-holder to kiss me on the cheek–if he held his woodsy treasure over my head. Since mistletoe could be spotted on the bare limbs of deciduouos trees around the time that Christmas came, kissing under mistletoe was part of my small-town’s Christmas holiday tradition. If there was a Christmas dance, you could bet your boots that mistletoe would dangle from every doorway. For years, I had no idea that kissing under mistletoe was a pagan tradition. Heck, I was at least 40 before I knew anything about paganism. Little did I know that my life had been paganism–in many ways.

Christmas Was Originally a Pagan Holiday.

“The Scriptures are wholly silent as to the date of Christ’s birth. The 25th of December, the winter solstice, was not fixed as Christmas until a long time after the New Testament period. But in spite of serious objections, historical and otherwise, that date triumphed.The winter solstice was the date of the birth of Osiris, son of Isis the[279] Egyptian Queen of Heaven. Lewis, Abram Herbert, pg. 279.

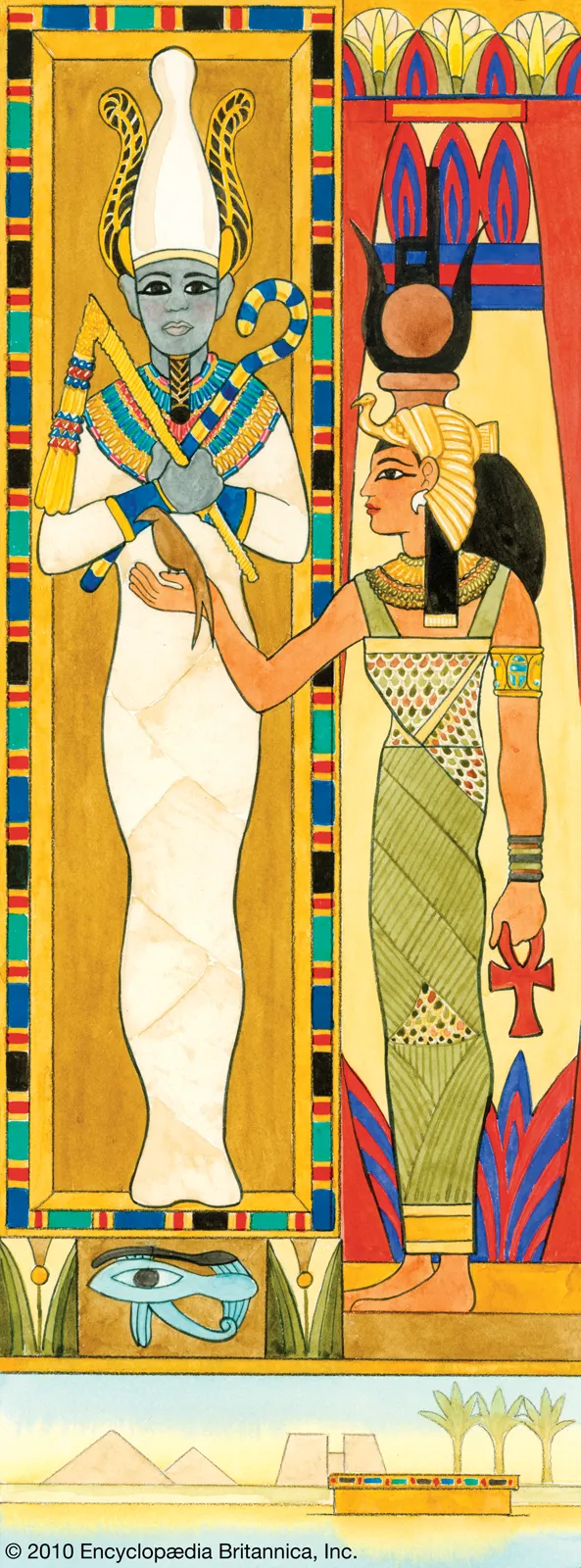

Isis and OsirisIsis (right) and Osiris.

Isis and OsirisIsis (right) and Osiris.

Image Credit: Britannica

Saturn driving a quadriga on the reverse of a denarius issued by Saturninus – Image Credit: Wikipedia

Saturn driving a quadriga on the reverse of a denarius issued by Saturninus – Image Credit: Wikipedia

“The term ‘Yule,’ another name for Christmas, comes from the Chaldee, and signifies ‘child’s day.’ This name for the festival was familiar to our Anglo-Saxon ancestors, long before they knew anything of Christianity. In Rome, this winter-solstice festival was Saturn’s festival; the wild, drunken, licentious “Saturnalia.” It was observed in Babylonia in a similar manner. When it came into Christianity its leading features were like those of the Saturnalia. These have been far too prevalent from that time. Lighted candles and ornamented trees were a part of the observance of the festival among the pagans. The “Christmas goose” and “Yule cakes” came, with the day, from paganism.” Egyptian Queen of Heaven. Lewis, Abram Herbert, pg. 279.

“Saturn is associated with a major religious festival in the Roman calendar, Saturnalia. Saturnalia celebrated the harvest and sowing, and ran from December 17–23.” Wikipedia

Easter.

“The earliest Christians continued to observe the Jewish Passover on the 14th of the month Nisan. As the pagan element increased in the Church, and the anti-Jewish feeling accordingly, after a sharp struggle, the time was changed from the fourteenth of the month to the Sunday nearest the vernal equinox.” Lewis, Abram Herbert, pg. 279.

“vernal equinox, two moments in the year when the Sun is exactly above the Equator and day and night are of equal length; also, either of the two points in the sky where the ecliptic (the Sun’s annual pathway) and the celestial equator intersect. In the Northern Hemisphere the vernal equinox falls about March 20 or 21, as the Sun crosses the celestial equator going north.” Britannica

“This brought it in conjunction with the festival of the Goddess of Spring, an ancient pagan feast, which probably dates back to the time of Astarte-worship….” Lewis, Abram Herbert, pgs. 279-80

‘Astarte, great goddess of the ancient Middle East and chief deity of Tyre, Sidon, and Elat, important Mediterranean seaports. Hebrew scholars now feel that the goddess Ashtoreth mentioned so often in the Bible is a deliberate conflation of the Greek name Astarte and the Hebrew word boshet, “shame,” indicating the Hebrews’ contempt for her cult. Ashtaroth, the plural form of the goddess’s name in Hebrew, became a general term denoting goddesses and paganism.” Britannica

Ostara by Johannes Gehrts. The goddess flies through the heavens surrounded by Roman-inspired putti, beams of light, and animals. Germanic people look up at the goddess from the realm below.

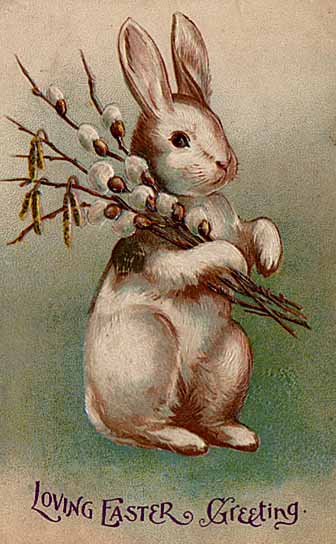

‘…in Babylonia. The name “Easter” is comparatively modern. It comes from Oestra,[280] the Goddess of Spring, in the Northern European mythology. The forms of observance were almost wholly heathen. Easter eggs, dyed, and “hot cross-buns,” figured in the Chaldean Easter, as they have done in the Christian. The Hindus, and Chinese, and Egyptians had a sacred egg, the history of which can be traced to the Euphrates and the worship of Astarte.” Lewis, Abram Herbert, pg. 280.

Ēostre(Proto-Germanic: *Austrō(n)) is a West Germanic spring goddess. The name is reflected in Old English: *Ēastre ([ˈæːɑstre]; Northumbrian dialect: Ēastro, Mercian and West Saxon dialects: Ēostre [ˈeːostre]),[1][2][3]Old High German: *Ôstara, and Old Saxon: *Āsteron.[4][5] By way of the Germanic month bearing her name (Northumbrian: Ēosturmōnaþ, West Saxon: Ēastermōnaþ; Old High German: Ôstarmânoth), she is the namesake of the festival of Easter in some languages. The Old English deity Ēostre is attested solely by Bede in his 8th-century work The Reckoning of Time, where Bede states that during Ēosturmōnaþ (the equivalent of April), pagan Anglo-Saxons had held feasts in Ēostre’s honour, but that this tradition had died out by his time, replaced by the Christian Paschal month, a celebration of the resurrection of Jesus. …

Image Credit: Wikipedia

“Theories connecting Ēostre with records of Germanic Easter customs, including hares and eggs, have been proposed. Whether the goddess was an invention of Bede has been a debate among some scholars, particularly prior to the discovery of the matronae Austriahenae and further developments in Indo-European studies. Due to these latter developments, she is generally accepted as a genuine pagan goddess among modern scholars. Ēostre and Ostara are sometimes referenced in modern popular culture and are venerated in some forms of Germanic neopaganism. …

“According to linguist Guus Kroonen, the Germanic and Baltic languages replaced the old formation *h₂éws-os, the name of the PIE dawn-goddess, with a form in *-reh₂-, likewise found in the Lithuanian deity Aušrinė.[5] In Anglo-Saxon England, her springtime festival gave its name to a month (Northumbrian: Ēosturmōnaþ, West Saxon: Eastermonað),[7] the rough equivalent of April, then to the Christian feast of Easter that eventually displaced it.[4][8]

“In southern Medieval Germany, the festival Ôstarûn similarly gave its name to the month Ôstarmânôth, and to the modern feast of Ostern (‘Easter’), suggesting that a goddess named *Ôstara was also worshipped there.[9][8] The name of the month survived into 18th-century German as Ostermonat.[10] An Old Saxon equivalent of the spring goddess named *Āsteron may also be reconstructed from the term asteronhus, which is translated by most scholars as ‘Easter-house’, …

“Frankish historian Einhard also writes in his Vita Karoli Magni (early 9th century CE) that after Charlemagne defeated and converted the continental Saxons to Christianity, he gave Germanic names to the Latin months of the year, which included the Easter-month Ostarmanoth.[12]

“Frankish historian Einhard also writes in his Vita Karoli Magni (early 9th century CE) that after Charlemagne defeated and converted the continental Saxons to Christianity, he gave Germanic names to the Latin months of the year, which included the Easter-month Ostarmanoth.[12]” Wikipedia

Lent.

“Lent has been given some appearance of having a Christian origin by the assumption, for which there is not a shadow of scriptural, or even apostolic authority, that it is the counterpart of Christ’s fast of forty days. But the history of Lent shows unmistakably its pagan origin. Its source is found in the fasting which the Babylonians associated with the Goddess of Reproduction, whose worship formed the starting-point of Easter. During that period of fasting, social joy and all expressions of sexual regard were forbidden, because the goddess then mourned the loss of her consort. From this came the germ of Lent, and especially the practice of abstaining from marriage at that season.

“The pagan tribes of Koordistan still keep such a fast. Humboldt found the same in Mexico, and Landseer in Egypt. It came into Christianity[281] comparatively slowly, and brought gross evils with it. Witness the following:

“This change of the calendar in regard to Easter was attended with momentous consequences. It brought into the Church the grossest corruption, and the rankest superstition in connection with the abstinence of Lent. Let any one only read the atrocities that were commemorated during the ‘sacred fast’ or pagan Lent, as described by Arnobius and Clemens Alexandrinus, and surely he must blush for the Christianity of those, who with the full knowledge of all these abominations ‘went down to Egypt for help’ to stir up the languid devotion of the degenerate Church, and who could find no more excellent way to ‘revive’ it than by borrowing from so polluted a source; the absurdities and abominations connected with which the early Christian writers held up to scorn.”[249]

“Many devout Christians now observe Lent without taint of paganism; but with the undevout, Lent is only a resting time from the fashionable dissipation of “society,” which refreshes them for the excesses that follow Easter.Lewis, Abram Herbert

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.