In a Norse tale, the god Odin went to Urda’s well to seek knowledge.

The sacred water of Urda’s well was under the great root of Ygdrassil, and Ygdrassil was a sacred tree–the Tree of Life in Norse Mythology.

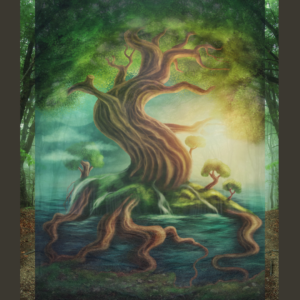

The Tree of life.

“Whatever may have been the site of the land of Eden or Pleasure, Moses, in describing Paradise as its garden (much as we speak of Kent as the Garden of England), doubtless wished to convey the idea of a sanctuary of delight and primal loveliness; indeed, he tells us that “out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food.” This Paradise was in the middle of Eden, and in the middle of Paradise was planted the Tree of Life, and, close by, the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Into this garden the Lord put the man whom He had formed, “to dress and to keep it,” in other words to till, plant, and sow.

“In the very centre of Paradise, in the midst of the land of Eden, grew the Tree of Life. Now, what was this tree? Various have been the conjectures with regard to its nature. The traditions of the Rabbins make the Tree of Life a supernatural tree, resembling the world- or cloud-trees of the Scandinavians and Hindus, and bearing a striking resemblance to the Tooba of the Mahomedan Paradise. They describe the Tree of Life as being of enormous bulk, towering far above all others, and so vast in its girth, that no man, even if he lived so long, could travel round it in less than five hundred years. From beneath the colossal base of this stupendous tree gushed all the waters of the earth, by whose instrumentality nature was everywhere refreshed and invigorated. Regarding these Rabbinic traditions as purely mythical, certain commentators have regarded the Tree of Life as typical only of that life and the continuance of it which our first parents derived from God. Others think that it was called the Tree of Life because it was a memorial, pledge, and seal of the eternal life which, had man continued in obedience, would have been his reward in the Paradise above. Others, again, believe that the fruit of it had a certain vital influence to cherish and maintain man in immortal health and vigour till he should have been translated from the earthly to the heavenly Paradise.

“Dr. Wild considers that the Tree of Life stood on Mount Moriah, the very spot selected, in after years, by Abraham, whereon to offer his son Isaac, the type, and the mount to which Christ was led out to be sacrificed. As Eden occupied the centre of the world, and the Tree of Life was planted in the middle of Eden, that spot marked the very centre of the world, and it was necessary that He who was the life of mankind should die in the centre of the world, and act from the centre. Hence, the Tree of Life, destroyed at the flood, on account of man’s wickedness, was replaced on the same spot, centuries after, by the Cross,—converted by the Redeemer into a second and everlasting Tree of Life.

“Adam was told he might eat freely of every tree in the garden, excepting only the Tree of Knowledge; we may, therefore, suppose that he would be sure to partake of the fruit of the Tree of Life, which, from its prominent position “in the midst of the garden,” would naturally attract his attention. Like the sacred Soma-tree of the Hindus, the Tree of Life probably yielded heavenly ambrosia, and supplied to Adam food that invigorated and refreshed him with its immortal sustenance. So long as he remained in obedience, he was privileged to partake of this glorious food; but when, yielding to Eve’s solicitations, he disobeyed the Divine command, and partook of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, he found it had given to him the knowledge of evil—something of which he had hitherto been in happy ignorance. He had sinned; he was no longer fit to taste the immortal ambrosia of the Tree of Life; he was, therefore, driven forth from Eden, and lest he should be tempted once again to return and partake of the glorious fruit of the immortalising tree, God “placed at the east of the Garden of Eden cherubims and a flaming sword, which turned every way, to keep the way of the Tree of Life.” Henceforth the immortal food was lost to man: he could no longer partake of that mystic fruit which bestowed life and health. Dr. Wild is of opinion that the Tree of Knowledge stood on Mount Zion, the spot afterwards selected by the Almighty for the erection of the Temple; because, through the Shechinah, men could there obtain knowledge of good and evil.” W. Y. Evans-Wentz. The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries.

Some have claimed that the Banana, the Musa paradisiaca, was the Tree of Life, and that another species of the tree, the Musa sapientum, was the Tree of Knowledge; others consider that the Indian sacred Fig-tree, the Ficus religiosa, the Hindu world-tree, was the Tree of Life which grew in the middle of Eden; and the Bible itself contains internal evidence supporting this idea. In Gen. iii. 8, we read that Adam and Eve, conscious of having sinned, “hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God amongst the trees of the garden.” Dr. Wright, however, in his Commentary, remarks that, in the original, the word rendered “trees” is singular—“in the midst of the tree of the garden”—consequently, we may infer that Adam and Eve, frightened by the knowledge of their sin, sought the shelter of the Tree of Life—the tree in the centre of the garden; the tree which, if it were the Ficus religiosa, would, by its gigantic stature, and the grove-like nature of its growth, afford them agreeable shelter, and prove a favourite retreat. Beneath the shade of this stupendous Fig-tree, the erring pair reflected upon their lost innocence; and in their conscious shame, plucked the ample foliage of the tree, and made themselves girdles of Fig-leaves. Here they remained hidden beneath the network of boughs which drooped almost to the earth, and thus formed a natural thicket within which they sought to hide themselves from an angry God.

The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.

The Tree of Knowledge, in the opinion of some commentators, was so called, not because of any supernatural power it possessed of inspiring those who might eat of it with universal knowledge, as the serpent afterwards suggested, but because by Adam and Eve abstaining from or eating of it after it was prohibited, God would see whether they would prove good or evil in their state of probation.

The tradition generally accepted as to the fruit which the serpent tempted Eve to eat, fixes it as the Apple, but there is no evidence in the Bible that the Tree of Knowledge was an Apple-tree, unless the remark, “I raised thee up under the Apple-tree,” to be found in Canticles viii., 5, be held to apply to our first parents. Eve is stated to have plucked the forbidden fruit because she saw that it was good for food, that it was pleasant to the eyes, and that the tree which bore it was “to be desired to make one wise.”

According to an Indian legend, it was the fruit of the Banana tree (Musa paradisiaca or M. sapientum) that proved so fatal to Adam and Eve. We read in Gerarde’s ‘Herbal,’ that “the Grecians and Christians which inhabit Syria, and the Jewes also, suppose it to be that tree of whose fruit Adam did taste.” Gerarde himself calls it “Adam’s Apple-tree,” and remarks of the fruit, that “if it be cut according to the length oblique, transverse, or any other way whatsoever, may be seen the shape and forme of a crosse, with a man fastened thereto. My selfe have seene the fruit, and cut it in pieces, which was brought me from Aleppo, in pickle; the crosse, I might perceive, as the forme of a spred-egle in the root of Ferne, but the man I leave to be sought for by those which have better eies and judgement than my selfe.” Sir John Mandeville gives a similar account of the cross in the Plantain or “Apple of Paradise.” In a work by Léon, called ‘Africa,’ it is stated that the Banana is in that country generally identified with the Tree of Adam. “The Mahometan priests say that this fruit is that which God forbade Adam and Eve to eat; for immediately they eat they perceived their nakedness, and to cover themselves employed the leaves of this tree, which are more suitable for the purpose than any other.” To this day the Indian Djainas are by their laws forbidden to eat either Bananas or Figs. Vincenzo, a Roman missionary of the seventeenth century, after stating that the Banana fruit in Phœnicia bears the effigy of the Crucifixion, tells us that the Christians of those parts would not on any account cut it with a knife, but always broke it with their hands. This Banana, he adds, grows near Damascus, and they call it there “Adam’s Fig Tree.” In the Canaries, at the present time, Banana fruit is never cut across with a knife, because it then exhibits a representation of the Crucifixion. In the island of Ceylon there is a legend that Adam once had a fruit garden in the vicinity of the torrent of Seetagunga, on the way to the Peak. Pridham, in his history of the island, tells us that from the circumstance that various fruits have been occasionally carried down the stream, both the Moormen and Singalese believe that this garden still exists, although now inaccessible, and that its explorer would never return. Tradition, however, affirms that in the centre of this Ceylon Paradise grows a large Banana-tree, the fruit of which when cut transversely exhibits the figure of a man crucified, and that from the huge leaves of this tree Adam and Eve made themselves coverings.

Certain commentators are of opinion that the Tree of Knowledge was a Fig-tree—the Ficus Indica, the Banyan, one of the sacred trees of the Hindus, under the pillared shade of which the god Vishnu was fabled to have been born. In this case the Fig-tree is a tree of ill-omen—a tree watched originally by Satan in the form of a serpent, and whose fruit gave the knowledge of evil. After having tempted and caused Adam to fall by means of its fruit, its leaves were gathered to cover nakedness and shame. Again, the Fig was the tree which the demons selected as their refuge, if one may judge from the fauni ficarii, whom St. Jerome recognised in certain monsters mentioned by the prophets. The Fig was the only tree accursed by Christ whilst on earth; and the wild Fig, according to tradition, was the tree upon which the traitor Judas hanged himself, and from that time has always been regarded as under a bane.

The Citron is held by many to have been the forbidden fruit. Gerarde tells us that this tree was originally called Pomum Assyrium, but that it was known among the Italian people as Pomum Adami; and, writes the old herbalist, “that came by the opinion of the common rude people, who thinke it to be the same Apple which Adam did eate of in Paradise, when he transgressed God’s commandment; whereupon also the prints of the biting appeare therein as they say; but others say that this is not the Apple, but that which the Arabians do call Musa or Mosa, whereof Avicen maketh mention: for divers of the Jewes take this for that through which by eating Adam offended.”

The Pomegranate, Orange, Corn, and Grapes have all been identified as the “forbidden fruit;” but upon what grounds it is difficult to surmise.

After their disobedience, Adam and Eve were driven out of Paradise, and, according to Arabian tradition, Adam took with him three things—an ear of Wheat, which is the chief of all kinds of food; Dates, which are the chief of fruits; and the Myrtle, which is the chief of sweet-scented flowers. Maimonides mentions a legend, cherished by the Nabatheans, that Adam, when he reached the district about Babylon, had come from India, carrying with him a golden tree in blossom, a leaf that no fire would burn, two leaves, each of which would cover a man, and an enormous leaf plucked from a tree beneath whose branches ten thousand men could find shelter.

Many ancient stories tell of sacred trees–and trees of life. In ancient Irish mythology, a cult worshipped sacred trees. The Druids of ancient Irisih mythology are closely connected to trees.

The Cult of Sacred Trees

“The things said of sacred waters can also be said of sacred trees among the Celts; and, in the case of sacred trees, more may be added about the Druids and their relation to the Fairy-Faith, for it is well known that the Druids held the oak and its mistletoe in great religious veneration, and it is generally thought that most of the famous Druid schools were in the midst of sacred oak-groves or forests. Pliny has recorded that ‘the Druids, for so they call their magicians, have nothing which they hold more sacred than the mistletoe[523] [Pg 434]and the tree on which it grows, provided only it be an oak (robur). But apart from that, they select groves of oak, and they perform no sacred rite without leaves from that tree, so that the Druids may be regarded as even deriving from it their name interpreted as Greek’[524] (a disputed point among modern philologists). Likewise of the Druids, Maximus Tyrius states that the image of their chief god, considered by him to correspond to Zeus, was a lofty oak tree;[525] and Strabo says that the principal place of assembly for the Galatians, a Celtic people of Asia Minor, was the Sacred Oak-grove.[526]

“Just as the cult of fountains was absorbed by Christianity, so was the cult of trees. Concerning this, Canon Mahé writes:—‘One sees sometimes, in the country and in gardens, trees wherein, by trimming and bending together the branches, have been formed niches of verdure, in which have been placed crosses or images of certain saints. This usage is not confined to the Morbihan. Our Lady of the Oak, in Anjou, and Our Lady of the Oak, near Orthe, in Maine, are places famous for pilgrimage. In this last province, says a historian, “One sees at various cross-roads the most beautiful rustic oaks decorated with figures of saints. There are seen there, in five or six villages, chapels of oaks, with whole trunks of that tree enshrined in the wall, beside the altar. Such among others is that famous chapel [Pg 435]of Our Lady of the Oak, near the forge of Orthe, whose celebrity attracts daily, from five to six leagues about, a very great gathering of people.”’[527]

“Saint Martin, according to Canon Mahé, tried to destroy a sacred pine-tree in the diocese of Tours by telling the people there was nothing divine in it. The people agreed to let it be cut down on condition that the saint should receive its great trunk on his head as it fell; and the tree was not cut down.[527] Saint Germain caused a great scandal at Auxerre by hanging from the limbs of a sacred tree the heads of wild animals which he had killed while hunting.[527] Saint Gregory the Great wrote to Brunehaut exhorting him to abolish among his subjects the offering of animals’ heads to certain trees.[528]

“In Ireland fairy trees are common yet; though throughout Celtdom sacred trees, naturally of short duration, are almost forgotten. In Brittany, the Forest of Brocéliande still enjoys something of the old veneration, but more out of sentiment than by actual worship. A curious survival of an ancient Celtic tree-cult exists in Carmarthen, Wales, where there is still carefully preserved and held upright in a firm casing of cement the decaying trunk of an old oak-tree called Merlin’s Oak; and local prophecy declares on Merlin’s authority that when the tree falls Carmarthen will fall with it. Perhaps through an unconscious desire on the part of some patriotic citizens of averting the calamity by inducing the tree-spirit to transfer its abode, or else by otherwise hoodwinking the tree-spirit into forgetting that Merlin’s Oak is dead, a vigorous and now flourishing young oak has been planted so directly beside it that its foliage embraces it. And in many parts of modern England, the Jack-in-the-Green, a man entirely hidden in a covering of green foliage who dances through the streets on May Day, may be another example of a very ancient tree (or else agricultural) cult of Celtic origin.” W. Y. Evans-Wentz. The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries.

Ancient Pagan Holidays Celebrated Today–Some of Them Are Celebrated as Christian

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.