Randolph

Caldecott:

A Personal Memoir

OF HIS EARLY ART CAREER.

BY

Henry Blackburn

NEW YORK: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS,

9, LAFAYETTE PLACE.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1886. Art

CHAPTER I.

HIS EARLY ART CAREER.

“Randolph Caldecott, the son of an accountant in Chester, was born in that city on the 22nd of March, 1846, and educated at the King’s School, where he became the head boy. He was not studious in the popular sense of the word, but spent most of his leisure time in wandering in the country round. Thus, his love of sport and fondness for rural pursuits, which never forsook him, were evidenced at an early age. His artistic instincts were also early developed, and many treasured[Pg 2] sketches, models of animals, &c., cut out of wood, were produced in Chester by the boy Caldecott.

“Perhaps the best and most characteristic record of his early life is, that he and his brother were “two of the best boys in the school;” the genius that consists in “an infinite faculty for taking pains” having much to do with his after career of success.

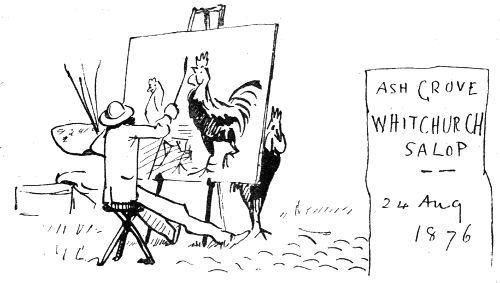

“In 1861 Caldecott was sent to a bank at Whitchurch in Shropshire, where, for six years, he seems to have had considerable leisure and opportunity for indulging in his favourite pursuits. Here, living at an old farm-house about two miles from the[Pg 3] town, he used to go fishing and shooting, to the meets of hounds, to markets and cattle fairs, gathering in a store of knowledge useful to him in after years….

“In 1861 Caldecott was sent to a bank at Whitchurch in Shropshire, where, for six years, he seems to have had considerable leisure and opportunity for indulging in his favourite pursuits. Here, living at an old farm-house about two miles from the[Pg 3] town, he used to go fishing and shooting, to the meets of hounds, to markets and cattle fairs, gathering in a store of knowledge useful to him in after years

One who knew him well at this time, writing in the Manchester Courier of Feb. 16th, 1886, says:—

“Caldecott used to wander about the bustling, murky streets of Manchester, sometimes finding himself in queer out-of-the-way quarters, often coming across an odd character, curious bits of antiquity and the like. Whenever the chance came, he made short excursions into the adjacent country, and long walks which were never purposeless. Then[Pg 6] he joined an artists’ club and made innumerable pen and ink sketches. Whilst in this city so close was his application to the art that he loved that on several occasions he spent the whole night in drawing.”

“For five years, from 1867 to 1872, Caldecott worked steadily at the desk in Manchester, studying from nature whenever he had the chance in summer; and at the school of art in the long evenings, sometimes working long and late at some water colour drawing. Caldecott owed much to Manchester, as he often said, and he never forgot or undervalued the good of his early training. The friends he made then he kept always, and they were amongst his dearest and best.

“In Manchester on the 3rd of July, 1868—his first drawings were published in a serio comic paper called Will o’ the Wisp; and in 1869, in another paper called The Sphinx, he had several pages of drawings reproduced. He was painting a little at the same time, making many hunting and other studies; they were chiefly for friends, but one picture was exhibited at the Manchester Royal Institution in 1869.

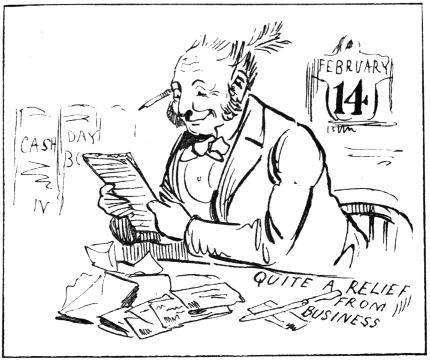

There was no restraining Caldecott now, his artistic bent and his delightful humour were finding expression in sketches in odd hours and minutes, on bits of note paper, on old envelopes, and on the blotting paper before him at his desk, until everybody about him must have been alive to his talent. He might no doubt have eventually attained a good position in the bank, for, as one of his friends writes of him very truly,

“Caldecott’s ability was general, not special. It found its natural and most agreeable outlet in art and humour, but everybody who knew him, and those who received his letters, saw that there were perhaps[Pg 10] a dozen ways in which he would have distinguished himself had he been drawn to them.”

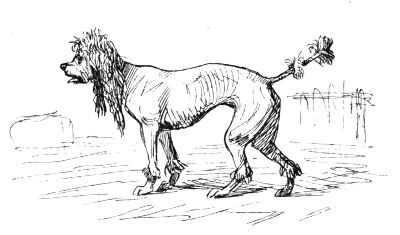

“The unpublished sketches dispersed through this chapter indicate but slightly the originality and fecundity of Caldecott’s genius at this time.

“And so, in May, 1870, Caldecott, as his diary records, went to London for a few days with a letter of introduction to Mr. Thomas Armstrong from Mr. W. Slagg; and in the same year, 1870, some of his drawings were shown to Shirley Brooks, and to Mark Lemon, then editor of Punch. Mr. Clough thus records the event:—

“Bearing an introductory letter he went up to London on a flying visit, carrying with him a sketch on wood and a small book of drawings of the ‘Fancies of a Wedding.’ He was well received. The sketch was accepted, and with many compliments the book of drawings was detained.

“From this date and all through the year 1871, Caldecott was at work in Manchester and sending to London drawings, some of which have hardly been exceeded for humour and expression in a few lines.

CHAPTER II.

DRAWING FOR “LONDON SOCIETY.”

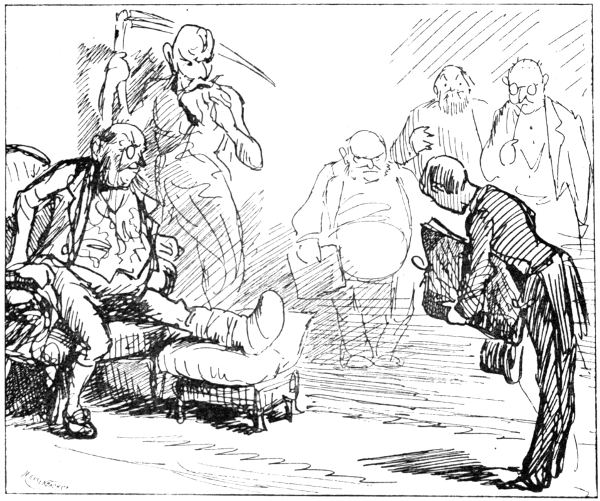

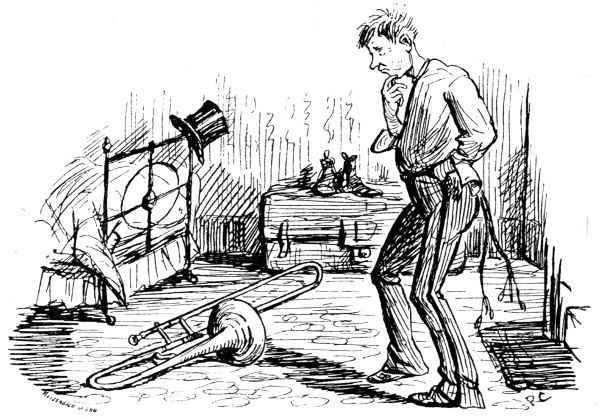

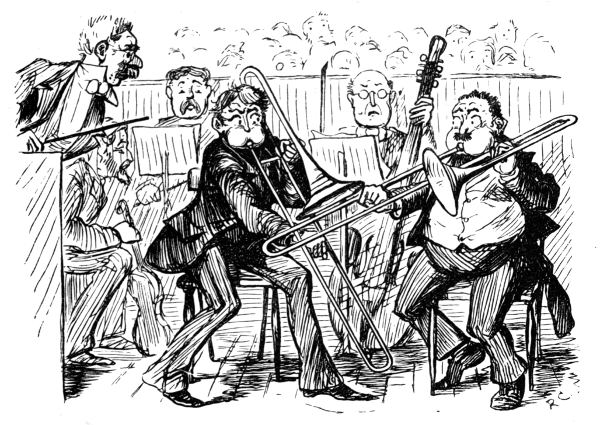

“For Christmas time, 1871, Caldecott made many sketches. Two were to illustrate a short story called “The Two Trombones,” by F. Robson, the actor. It was a ridiculous story, bordering on broad farce, depicting the adventures of Mr. Adolphus Whiffles, a young man from the country, who in order to get behind the scenes of a theatre undertakes to act as a substitute for a friend as “one of the trombones,” unknown to the leader of the orchestra. His friend[Pg 19] assures him that in a crowded assembly “one trombone would probably make as much noise as two,” and that, if he took his place in the orchestra, he had only to “pretend to play and all would be right.”

“In the first sketch we see him in his bedroom contemplating the unfamiliar instrument left by his friend; in the second he is at the theatre at the crisis when the leader of the band calls upon him to “play in” (as it is called) one of the performers on to the stage! Mr. Whiffles’s instructions were[Pg 20] to keep his eyes on the other trombone and imitate his movements exactly; but unfortunately the other trombone was a substitute also. The leader looks round, and seeing the two trombones apparently perfectly ready to begin, gives the signal, and the curtain rises. The dénoûment may be imagined! Other stories were illustrated by Caldecott, about this period, in London Society; one of Indian life, another called Crossed in Love, &c., but the artist wished that some illustrations should not be reprinted. Several drawings from London Society are omitted, from the same cause.

. . .

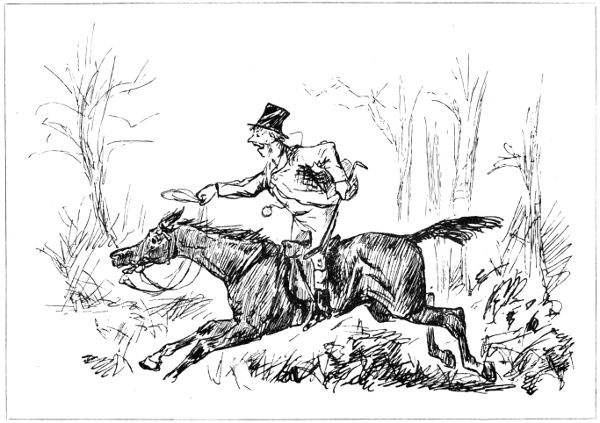

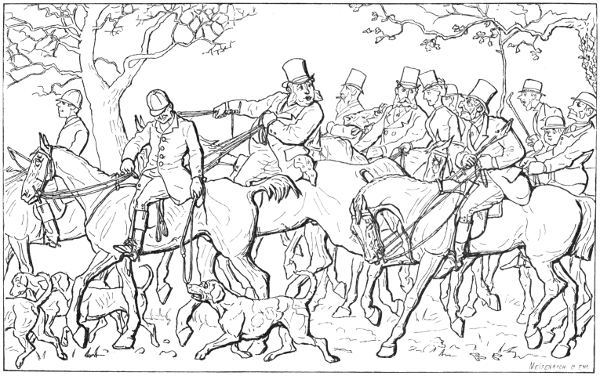

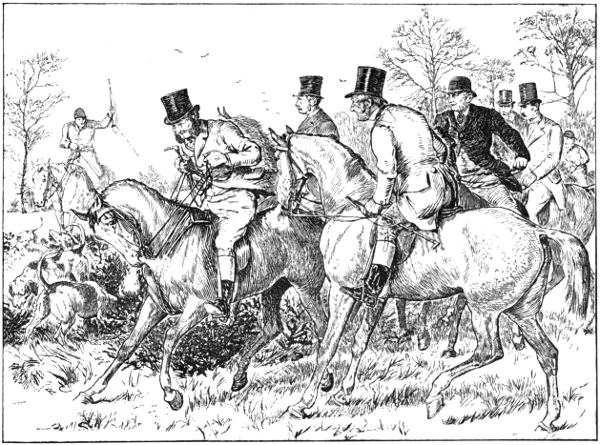

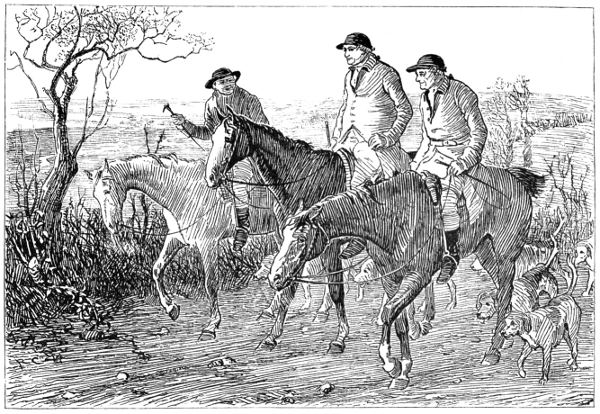

Going to Cover

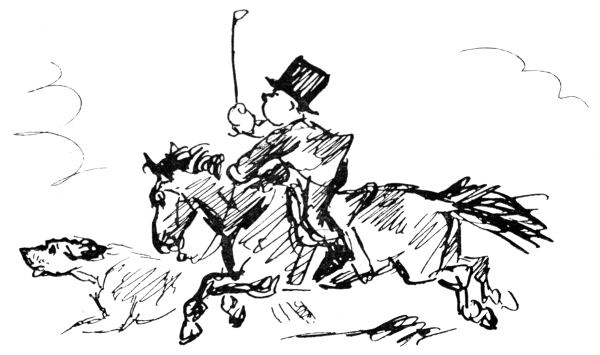

“Amongst the most ambitious and interesting of Caldecott’s drawings at this time were his “hunting and shooting friezes,” of which several examples will be found in the pages of London Society for 1871 and 1872, drawn in outline with a pen; showing, thus early, much decorative feeling and a liking for design in relief which never left him in after years.

Two of the best that he did were the hunting subjects, entitled “Going to Cover” and “Full Cry.”

. . .

CHAPTER III.

IN LONDON, THE HARZ MOUNTAINS, ETC

“Early in the year 1872 Caldecott left Manchester for London, “bearing with him the well wishes of the Brazenose Club and of an extensive circle of friends.” This great change was not decided upon without considerable hesitation; but, to quote again from a Manchester letter:—

“Caldecott was greatly encouraged to take this step by the sale of some small oil and water colour paintings at modest prices, and by the acceptance of drawings by London periodicals. The clinking of sovereigns and the rustling of bank-notes became[Pg 30] sounds of the past—the fainter the pleasanter, so at least Caldecott thought at that time, with energy, ardour, and the world before him.”

In February and March, 1872, he was still drawing for the magazines and illustrating short stories.

In March, 1872, he exhibited hunting sketches in oil at the Royal Institution, Manchester.

On the 16th April he went to the Slade School to attend the Life Class under E. J. Poynter, R.A., until the 29th June.

As this was the turning point in Caldecott’s career, it should be recorded that at this time, and ever afterwards, Mr. Armstrong, the present Art Director at the South Kensington Museum, was his best friend and counsellor.[2] He had also the advantage of the friendship of George du Maurier, M. Dalou, the sculptor, Charles Keene, Albert Moore, and others.

On the 8th June he records, “A. urged me to prepare caricatures of people well known,” probably with the view of making drawings for periodicals.

[Pg 31]

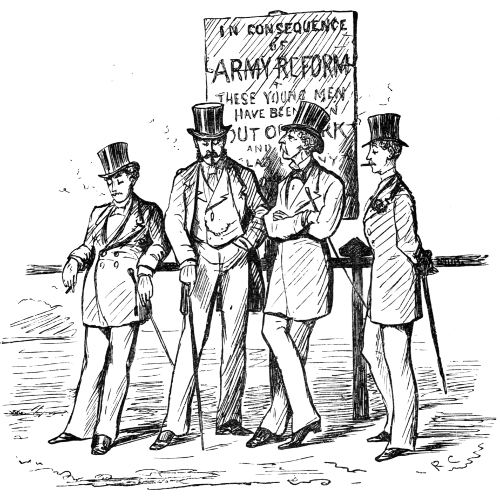

Several drawings of Caldecott’s were under consideration by the proprietors of Punch, and on the 22nd June, 1872, the first appeared.

In the same month he exhibited a frame of four small sepia drawings at the Black and White Exhibition, Egyptian Hall, London.

. . .

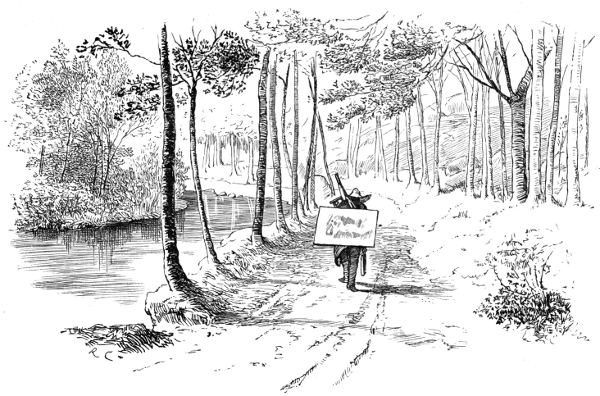

Caldecott’s First Illustrated Book

“About this time it was suggested to him to illustrate a book of summer travel, and on the 20th August 1872 he enters in his diary:—

“To Rotterdam, Harzburg, &c., to join Mr. and Mrs. B. in the Harz Mountains.”

[Pg 33]

“This was the first book that Caldecott illustrated;[3] the[Pg 34] title suggested was “A Tour in the Toy Country,” and before leaving London he made the drawing on the preceding page. Caldecott, being then twenty-six, started on this journey with great readiness. The idea was altogether delightful to him; and here, as in every country he visited in after years, his playful fancy and facility for seizing the grotesque side of things stood him in good stead.

In a strange land, amidst unfamiliar scenes and faces, he roamed “fancy free”; in a country so compact in size that the whole could be traversed in a month’s walking tour.

“With Baedeker’s Guide (English edition) in his pocket, and a dialogue book of sentences in[Pg 35] German and English, he used to delight to interrogate the wondering natives; the necessary questions difficult to find, and “the elaborate and quite unnecessary” (as he expressed it), always turning up. Such little incidents gave opportunity to the observant artist to study the faces of the listeners; the interviews conducted slowly and gravely, and ending in a peal of laughter from the natives.

. . .

CHAPTER IV.

DRAWING FOR “THE DAILY GRAPHIC.

“Some idea of the work on which Caldecott was engaged in 1873 and 1874, may be gathered from extracts from his diary in those years. They are interesting if only to show that at that early period his art studies were varied, and that his experience was not confined to book illustration as has generally been supposed.

[Pg 52]

In January, 1873, he made six illustrations for Frank Mildmay by “Florence Marryatt,” and on January 22nd, an “Initial for Punch.”

In February—

“Began wax-modelling for practice, hearing that my hunting frieze (white on brown paper) had been successful in Manchester, and that I should perhaps be asked to model some animals for a chimney-piece.”

24th April.—”A. came to see my wax models; liked them, said I must do something further.”

. . .

Chapter IV

“About the middle of February I went down into the country to make some studies and sketches, and remained more than a month. Had several smart attacks on my heart, a little wounded once, causing that machine to go up and down like a lamb’s tail when its owner is partaking of the nourishment provided by a bounteous Nature. Further particulars in our next—no more paper now. I hope you and —— are well, and with kind regards, remain yours faithfully,

[Pg 55]

In May he is “working in clay in low relief.”

6th June.—”Began modelling mare and foal in round.”

In the latter part of June, and in July, he is “at Vienna with Mr. Blackburn,” engaged on various illustrations for the Daily Graphic.

It was in the summer of 1873 that it occurred to the proprietors of the Daily Graphic (the American illustrated newspaper referred to) that the Gulf Stream, and the strong prevailing current of wind easterly from the continent of America in that latitude, might be turned to profitable account for advertising purposes. They constructed a large balloon which hung high above the houses in Broadway for some weeks, and announced that on a certain day the Daily Graphic balloon would sail for Europe. The start was telegraphed to London and gravely[Pg 57] announced in the Times and other London papers, and every one was on the qui vive for this new arrival in the air.

. . .

The humour and vivacity, the abandon, so to speak, exhibited in some of these early drawings, form a delightful episode in his early art career, and many will wonder, looking at the variety of movement and expression (in the drawing of the overloaded car, for instance), that the artist should have been amongst us so long without more recognition. It is true that his drawings were[Pg 61] uncertain, and that the results of want of training were sometimes too palpable; that the accusation made in 1872 that the editor of London Society had chosen “an artist who could not draw a lady,” could hardly be gainsaid in 1873.

The artistic interest in these drawings is great, if only from the fact that they are amongst the few of his works drawn in pen and ink for direct reproduction without the intervention of the wood-engraver. Caldecott was one of the first to try, and to avail himself of, the various methods of reproduction for the newspaper press; and in the pages of the Daily Graphic, his facile touch and play of line was made to appear with startling emphasis on the printed page.[6]

. . .

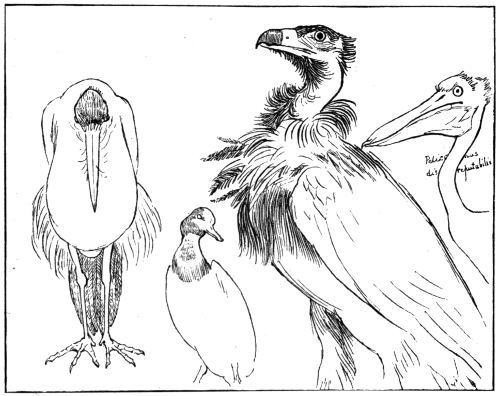

In the intervals of work Caldecott also made life studies at the Zoological Gardens in London, and anatomical studies of birds.

[Pg 65]

In September he made a drawing of Mark Twain lecturing in London, for the Daily Graphic, …

Chapter V

1874

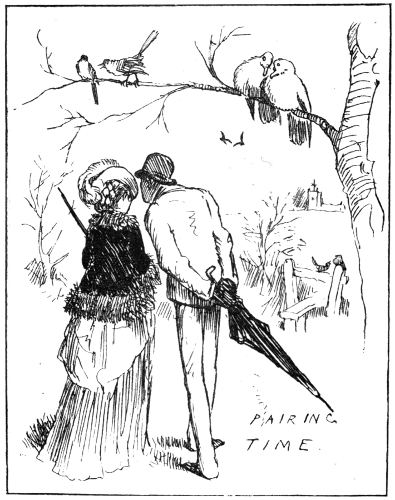

The Morning Walk

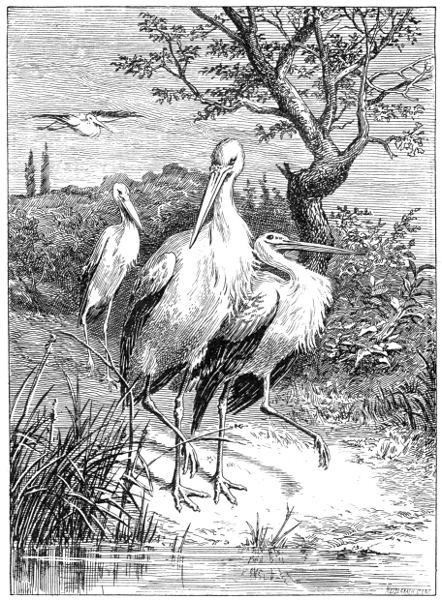

“The painting of swans, storks, and pigeons, referred to above, was very important work for Caldecott. In conjunction with his friend Mr. Armstrong, he painted the birds in two panels, one of swans (reproduced overleaf), and one of a stork and magpie. These panels were about six feet high, and form part of a series of decorations in[Pg 88] the dining-room of Mr. Henry Renshawe’s house at Bank Hall, near Buxton, Derbyshire.

Chapter VI

The Cottage Farnham Royal

During the summers of 1872, 1873, and 1874, Caldecott stayed often at a cottage belonging to the writer, three miles north of Slough, in Buckinghamshire, in the picturesque neighbourhood of Stoke Pogis and Burnham Beeches.

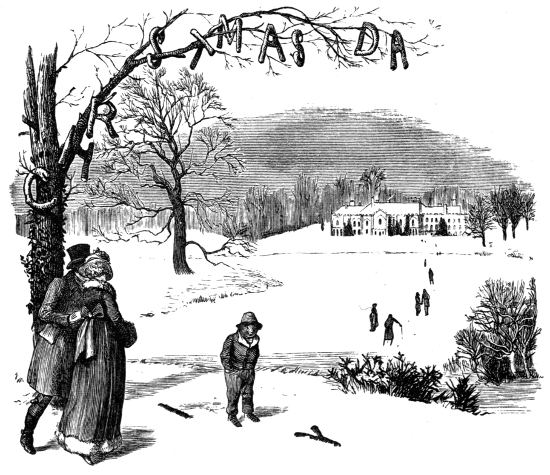

A “loose box” adjoining the stable—a few yards to the right of the little verandah in the above sketch—had been fitted up for him by friendly hands; and it was here in this temporary studio,[Pg 91] in the quiet of the country, looking out on woods and fields, that he made many of the drawings for Old Christmas.

Several entries in Caldecott’s diary in 1874 mention that in June and July he was “working in the ‘loose box’ at Farnham Royal, on the Sketch Book.”

During the summers of 1872, 1873, and 1874, Caldecott stayed often at a cottage belonging to the writer, three miles north of Slough, in Buckinghamshire, in the picturesque neighbourhood of Stoke Pogis and Burnham Beeches.

A “loose box” adjoining the stable—a few yards to the right of the little verandah in the above sketch—had been fitted up for him by friendly hands; and it was here in this temporary studio,[Pg 91] in the quiet of the country, looking out on woods and fields, that he made many of the drawings for Old Christmas.

Several entries in Caldecott’s diary in 1874 mention that in June and July he was “working in the ‘loose box’ at Farnham Royal, on the Sketch Book.”

Those were happy, irresponsible days, before great success had tempered his style, or brought with it many cares. Take the following letter (one of many) written in the full enjoyment of the change from lodgings in London

Those were happy, irresponsible days, before great success had tempered his style, or brought with it many cares.

. . .

During the summers of 1872, 1873, and 1874, Caldecott stayed often at a cottage belonging to the writer, three miles north of Slough, in Buckinghamshire, in the picturesque neighbourhood of Stoke Pogis and Burnham Beeches.

A “loose box” adjoining the stable—a few yards to the right of the little verandah in the above sketch—had been fitted up for him by friendly hands; and it was here in this temporary studio,[Pg 91] in the quiet of the country, looking out on woods and fields, that he made many of the drawings for Old Christmas.

Several entries in Caldecott’s diary in 1874 mention that in June and July he was “working in the ‘loose box’ at Farnham Royal, on the Sketch Book.”

Those were happy, irresponsible days, before great success had tempered his style, or brought with it many cares. Take the following letter (one of many) written in the full enjoyment of the change from lodgings in London:—

“We are fast drifting into a vortex of dissipation—eddying round a whirlpool of gaiety; but I hope that through all, our heads will keep clear enough to guide the helms of our hearts.”

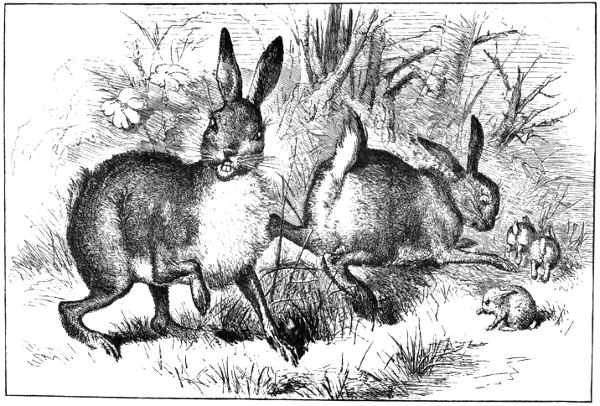

About this time it was suggested to Caldecott to make studies of animals and birds, with a view to an illustrated edition of Æsop’s Fables, a work for which his talents seemed eminently fitted. The idea was put aside from press of work, and when finally brought out in 1883 was not the success that had been anticipated. This was principally owing to the plan of the book.

. . .

Chapter VII

[1874 – Work on Washington Irving’s Old Christmas]

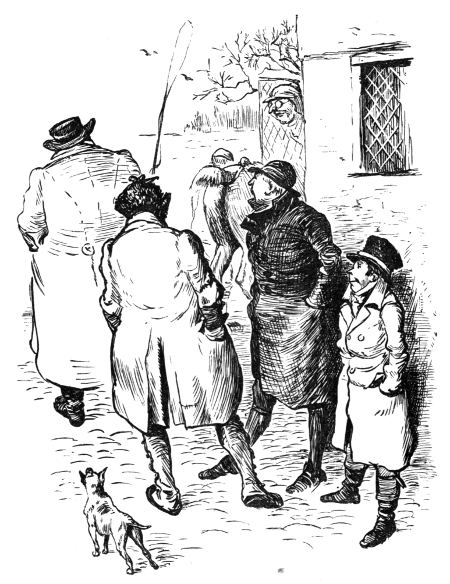

The Stage Coachman from Washington Irving’s Old Christmas

“All this costume is maintained with much precision; he has a pride in having his clothes of excellent materials; and notwithstanding the seeming grossness of his appearance, there is still discernible that neatness and propriety of person which is almost inherent in an Englishman. He[Pg 104] enjoys great consequence and consideration along the road; has frequent conferences with the village housewives, who look upon him as a man of great trust and dependence; and he seems to have a good understanding with every bright-eyed lass. The moment he arrives he throws down the reins with something of an air, and abandons the cattle to[Pg 105] the care of the ostler; his duty being merely to drive from one stage to another. When off the box his hands are thrust in the pockets of his greatcoat, and he rolls about the inn yard with an air of the most absolute lordliness. Here he is generally surrounded by an admiring throng of ostlers, stable-boys, shoe-blacks, and those nameless hangers-on that infest inns and taverns and run errands. Every ragamuffin that has a coat to his back thrusts his hands in his pockets, rolls in his gait, talks slang, and is an embryo ‘coachey.'”

Surely it has seldom happened in the history of illustration that an author should be so very closely followed—if not overtaken—by his illustrator. No literary touch seemed to be wanting from the author to convey a picture of English life and character passed away; but Caldecott’s coachman helps to elucidate the text; and whilst it carried to many a reader of Old Christmas in the New World a living portrait of a past age, it revealed also the presence of a new illustrator.

In the Stable Yard

Master Simon and His Dogs

It is interesting to note that Old Christmas was offered to, and declined by, one of the leading publishers in London; principally on the[Pg 110] ground that the illustrations were considered “inartistic, flippant and vulgar, and unworthy of the author of Old Christmas“! It was not until 1876 that the world discovered a new genius.

During the progress of the drawings for Old Christmas in 1874, Caldecott went with the writer to Brittany to make sketches for a new book; but the publication was postponed until after a more extended tour in 1878.

. . .

1874

On the 19th of November and following days Caldecott was “working at Dalou’s on a cat crouching for a spring.” He had a skeleton of a cat, a dead cat, and a live cat to work from. This model in clay was finished on the 8th December, 1874.

[Pg 115]

Christmas Eve was spent “in the caverns of the British Museum making a drawing, and measuring skeleton of a white stork.” This was a most elaborate and careful record of measurements. On the 28th of December he was “engaged on brown paper cartoon of storks at Armstrong’s,” and on the 30th is the entry,—”at British Museum; had storks out of cases to examine insertion of wing feathers.”

Thus, all through the year 1874 Caldecott, working without much recognition excepting from a few intimates, got through an immense amount of work; not forgetting his friends the children, to whom he sent many Christmas greetings with letters and coloured sketches. The drawing on the opposite page accompanied a kindly letter to a child of six years.

“I thank you,” he says, “very much for your grand sheet of drawings, which I think are very nice indeed. I hope you will go on trying and learning to draw. There are many beautiful things waiting to be drawn. Animals and flowers oh! such a many—and a few people.”

[Pg 116]

. . .

Chapter VIII

[Caldecott used a type of copying to help him illustrate]

Without going too far into technicalities, it may be interesting to illustrators to mention here that all Caldecott’s best drawings in his Picture Books, John Gilpin, The House that Jack Built, &c.; in the Graphic newspaper, and in Washington Irving’s[Pg 126] Old Christmas, &c., were photographed on to wood-blocks and have passed through the hands of the engraver.

The system of photographic engraving (by which the drawings are reproduced on pp. 124 and 125) bids fair to supersede wood-engraving for rapid journalistic purposes. It naturally attracted Caldecott in the first instance; but with increased knowledge and perception of “values,” and of the quality to be obtained in a good wood-engraving above any mechanical reproduction in relief, Caldecott was glad to avail himself of the help of the engraver. He drew with greater freedom, as he expressed it, preferring, as so many illustrators do, to put in tints with a brush, to be rendered in line by skilful engravers. But at the same time he delighted in shewing the power of line in drawing, studying “the art of leaving out as a science”; doing nothing hastily but thinking long and seriously before putting pen to paper, remembering, as he always said, “the fewer the lines, the less error committed.”

. . .

1875

Writing on the 27th of April, 1875, he says:—

“I feel I owe somebody an apology for staying in the country so long, but don’t quite see to whom it is due, so I shall stay two or three days longer, and then I shall indeed hang my harp on a willow[Pg 128] tree. It is difficult to screw up the proper amount of courage for leaving the lambkins, the piglets, the foals, the goslings, the calves, and the puppies. We want rain, and then things will grow with exceeding speed; as it is, the earth is dry and the buds are slow to display their hidden beauties. A little of ‘something to drink’ will cheer them, and then, like some human beings, they will look pleasant and cheerful and ‘come out.'”

. . .

Life in the country with Caldecott was “worth living,” and he chafed much at this period if he had to be with his “nose to the grindstone,” as he expressed it, in Bloomsbury. Whilst in the country[Pg 129] his letters to town were full of sketches, but in letters from London he hardly ever pictured life out of doors.

. . .

On the 4th of August he was “making designs for pelican picture;” and afterwards studying this subject at the Zoological Gardens. Two pictures of pelicans were eventually painted; the second,[Pg 131] in the possession of Mr. W. Phipson Beale, is sketched below.

. . .

{Old Christmas, written by Washington Irving and illustrated by Randolph Caldecott, was published and after that project, he began illustrating Bracebridge Hall]

In November 1875 he received the first copy of Old Christmas from the publishers, and already favourable notices of the illustrations had begun to appear in the newspapers.

. . .

1876

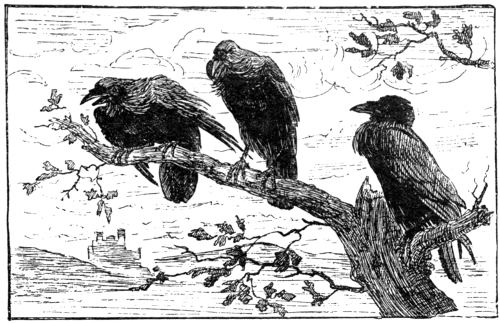

In this year, 1876, Caldecott exhibited his first painting in the Royal Academy, entitled, “There were Three Ravens sat on a Tree.” The humour and vigour of the composition are well indicated in the sketch. It was hung rather out of sight, above (and in somewhat grim proximity with) a picture of “At Death’s Door,” by Hubert Herkomer. Both artists were then thirty years of age.

. . .

In August he is writing from the country in high spirits as usual, and planning out much work for the future. Bracebridge Hall was finished, and the success of Old Christmas had brought him many commissions. His illustrations on wood had turned out well, being fortunate in his engravers, especially Mr. J. D. Cooper and Mr. Edmund Evans, who always rendered his work with sympathetic care. He may also be said to have been fortunate in his connection with the Graphic newspaper under the direction of Mr. W. L. Thomas, the artist and wood engraver.

[Pg 147]

But alas! in the autumn of this year his health failed him, and in October he was advised to go to Buxton in Derbyshire.

. . .

Chapter X

The journey to the Riviera and North Italy, which Caldecott was compelled to make for his health, before Christmas 1876, was as usual prolific of work.

. . .

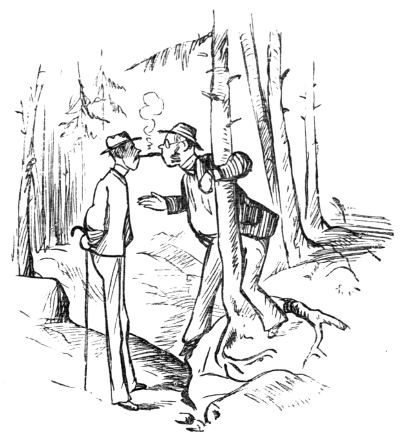

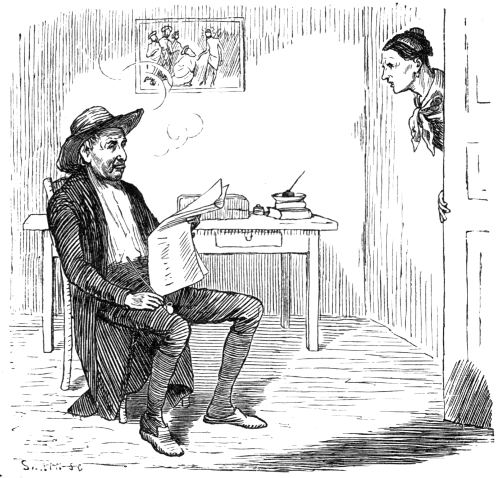

The Priest’s Servant Administers a Reproof

NORTH ITALIAN FOLK.

It was in the same winter, during his journey in North Italy, that Caldecott made twenty-eight illustrations for a book on North Italian Folk.[9] Here Caldecott’s studies, and his habit of sketching the peasantry wherever he went, served him well. Take the picture of the priest and his faithful servant Caterina; the latter, reproaching her master for bringing home a neighbour, Maddalena, “to eat two lasagne with us!” Caterina is “a gaunt threadbare-looking woman of some five-and-thirty[Pg 155] years, and the prevosto is gaunt too, and sallow; the two match well together. Caterina’s hair is smooth though scant, and her faded print dress is neat, but the bright yellow kerchief round her shoulders is soiled, and the cunning plaits of her grey hair are not as well ordered as the women’s are wont to be on mass days.

“Presently Caterina bustles into the darkened parlour, where sits the prevosto lazily smoking his[Pg 156] pipe and reading the country newspaper. He has put aside even the least of his clerical garments now, and lounges at ease in an old coat and slippers, his tonsured head covered by a battered straw hat.

“‘Listen to me,’ breaks forth the faithful woman, and she is not careful to modulate her voice even to a semblance of secrecy, ‘you don’t bring another mouth for me to feed here when it is baking day again. Per Bacco, no indeed!… It sha’n’t happen again, do you hear? And I have the holy wafers to bake besides. For shame of you! Come now to your dinner in the kitchen!’ And Caterina, the better for this free expression, hastens to dish up the minestra.

“‘Poor old priest! What a shrew he has got in his house,’ says some pitying reader. Yet he would not part with her for worlds! She is his solace and his right hand, and loves him none the less because of her sharp tongue and uncurbed speech. In many a lone and cheerless home of Italian priest can I call to mind such a woman as this—such a fond and faithful drudge, with harsh ways and a soft heart.”

The Husbandman

Another picture in North Italian Folk seems to give the character of the peasantry and the scenery exactly. “The sun glitters on the pale sea that is[Pg 157] down and away a mile or more beyond the sloping fields and gardens, and the dipping valley. Giovanni pauses to rest his burthen upon the wall just where the way turns to the right again, leaving the mountains and chestnut-clad hills behind it.”

Here in the sketch we are made to feel the sunlight and the glare from the sea on the southern slope; every detail of the pathway, to the stones in the old wall, being accurately given.

Never, perhaps, in any book since Washington Irving’s Old Christmas and Bracebridge Hall was the illustrator more in touch with the author than in North Italian Folk; but for some reason—probably because Caldecott’s work and style had become identified with English people and their ways, both abroad and at home—the illustrations made little impression. The completeness of the pictures, and the local colour infused into them by the author, left little to be done; moreover, Caldecott was not on his own ground, and to draw buildings and landscape in black and white, with the finish, and what is technically called the “colour,” considered necessary for a book of this kind, was always irksome to him.

Gossip

Less characteristic, but charming as a drawing, is the group of country girls under the cherry trees, reproduced on the opposite page. It is a picture worth having for its own sake, whether it aid the[Pg 160] text or not, and one with which we may fitly leave this volume.

. . .

Chapter XI

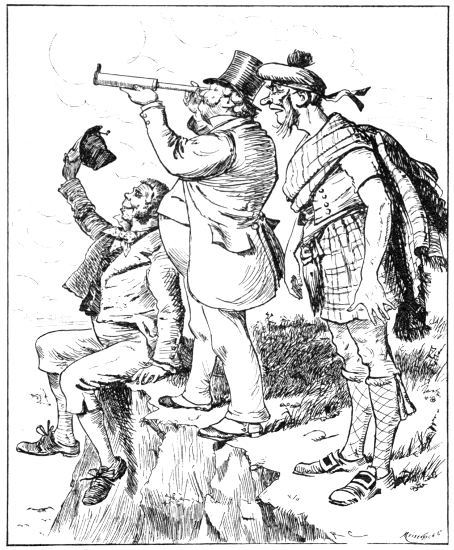

The Three Huntsmen (Oil Painting).

Royal Academy, 1878.

In 1878 he exhibited his picture of “The Three Huntsmen” riding home in evening light. It was hung rather high in Gallery VII. at the Royal Academy Exhibition, and technically could hardly be pronounced a success; but it was a distinct advance on previous exhibited work, and drew the serious attention of critics to Caldecott as a painter. The sketch appeared in an article on the Academy in L’Art, vol. xx. p. 211. Of this oil painting, Mr. Mundella, the late President of the Board of Trade writes:—

“The picture was bought by me of poor Caldecott in 1878. I think it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in that year, but I bought it from his easel. It is an oil painting, 3 ft. 6 in. by 2 ft. 9 in., and the subject is the ‘Three Huntsmen.’ I remember his bringing the song to my house after the purchase, and reading the song with great enjoyment, pointing out to us how he had illustrated the verse, ‘We hunted and we holloed till the setting of the sun.’ My little granddaughter (Millais’ ‘Dorothy Thorpe’) was his model for several of his Christmas books. She is the little girl in Sing a Song of Sixpence and several others, and possesses copies sent by him with little sketches and dedications. He is indeed a national loss.”

Early in 1878, Mr. Edmund Evans, the wood engraver, came to him with a proposal that he should illustrate some books for children to be printed in colours. The plan was soon decided upon, and the first of the Picture Books was begun. In the summer of the same year, Caldecott went with the writer for a second time to Brittany.

It was at first intended to take a gig and drive through and through, the country, giving an account of adventures from day to day, and Caldecott (who was more at home perhaps, in a gig than in any other position of life) favoured the idea; but time and other circumstances prevented.

The next proposal was to give a general description of the country and its people, its churches and ruined castles, as they exist to-day. But Caldecott did not take to this idea; he never in his lifetime drew buildings with the same facility as figures, and, at that time, to attempt to make drawings of chateaux, cathedrals and the like, would have been unsuccessful. So the book,[Pg 170] Brittany Picturesque, which had already been partly written, was laid aside to give space for sketches of Breton Folk.[10]

The Trap

“We obtained a trap in a few days”—not the gig, independent of a driver, which Caldecott always sighed for. His delight and high spirits on the first journey, in 1874, are seen in the sketch where he is waving farewell to some astonished peasantry. To be “on the road” was always a pleasure to Caldecott, from the “old Whitchurch days,” which[Pg 171] he often described to his friends—driving home in the dark at reckless speed after a late supper, in a dog-cart full of rather uproarious company—down to 1885 at Frensham, when as host, he would drive his friends in the lanes of Surrey.

At least 200 sketches must have been made in these journeys; besides jottings of heads, figures and the like, and several drawings in water colours.

Sketching Under Difficulties

The summer fêtes and “pardons,” all through the[Pg 172] country, [Breton] furnished capital material for his pencil, the women’s caps of different districts were each recorded, and here and there a solemn suggestive landscape noted for a picture which was never to be completed.

Breton Farmer and Cows

. . .

Writing from Pont Aven and recounting “the places which we have visited, done, sketched, interviewed and memorandumed”—he adds:[Pg 180]—

“On this journey I have seen more pleasing types of Bretons (and Bretonnes, especially) than in my former rambles in the Côtes du Nord; but there is generally something wrong about each hotel. This particular inn is comfortable. Seven Americans, two or three of them ladies, and about four French people dined with us, mostly of the artist persuasion.

A Cap of Finisterre.

A Cap of Finisterre.

“The village and the river sides, the meadows and the valleys reek with artists. A large gang pensions at another inn here.

“On approaching Pont Aven the traveller notices a curious noise rising from the ground and from the woods around him. It is the flicking of the paint brushes on the canvasses of the hardworking painters who come into view seated in leafy nooks and shady corners. These artists go not far from the town where is cider, billiards and tobacco.”

[Pg 181]

One of the best of Caldecott’s sketches here was “Returning from Labour,” a quiet spot on the banks of the Aven where he made several studies.

“Here we feel inclined for the first time to stay and sketch, wandering along the coast to the fishing villages, and visiting farms and homesteads.”

From another inn, in an “out of the way” part of Finisterre, he writes:—

“The Hotel du Midi where we put up is conducted in a simple manner; ladies would not like its arrangements. Several inhabitants, and a visitor or two, dine at the table d’hôte, but all are unable to carve a duck excepting the English visitor, who is accordingly put down as a cook.”

.

A Breton

. . .

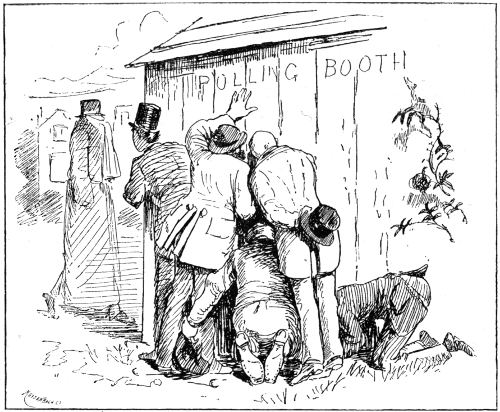

“Not such Disagreeable Weather after all—some People Think.”

From Punch, August 2nd, 1879.

. . .

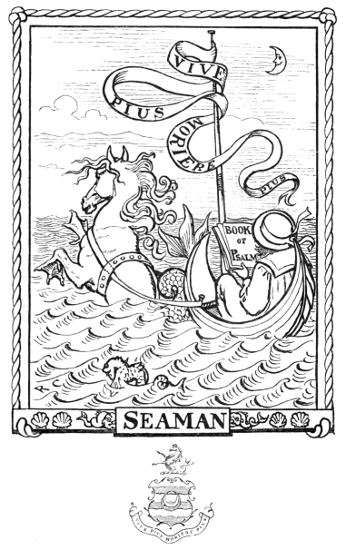

The book plate was drawn for an old and intimate friend in Manchester, and it[Pg 195] is curious to note how closely the style of the family crest is followed in its various details. If it were not for certain satirical touches this ingenious design might easily pass for the work of[Pg 196] other hands; the touch and treatment have little in common with Caldecott as he is known; but the artistic completeness of the little book plate is another evidence of his power as a designer.

Much drawing was accomplished in the spring of this year, both abroad, and on return to London. The success of his first Picture Books (on which he writes, “I get a small, small royalty”) was beyond all expectation, and the Elegy of a Mad Dog was now in progress.

. . .

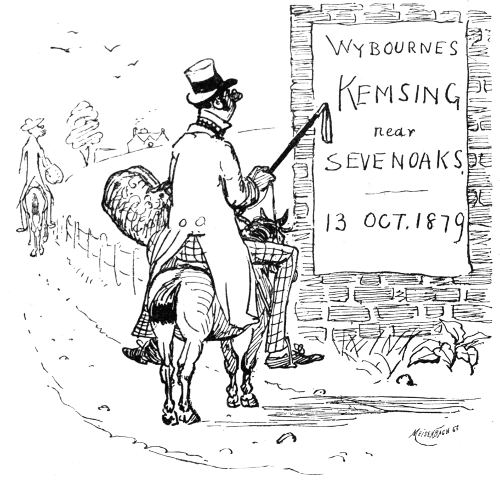

In 1879 he took a small house, with an old-fashioned garden, at Kemsing, near Sevenoaks. This was his first country home, “an out-of-the-way place,” as he expressed it, “but exactly right for me.” Here, surrounded by his four-footed friends, he could indulge his liking and love for the country.

. . .

Writing to a young friend on the 13th October, he sends the following:[Pg 198]—

“I am just now obliged to decline invitations to go and be merry with friends at a distance, because I am now living in this quiet, out-of-the-way village in order to make some studies of animals—to wit, horses, dogs, and other human beings—which I wish to use for the works that I shall be busy with during the coming winter.

“I have a mare—dark chestnut—who goes very well in harness, and is very pleasant to ride; and a little puppy—a comical young dachshund. My man calls the mare ‘Peri,’ so I call the puppy Lalla Rookh.”

In a letter to his friend Mr. Locker-Lampson, written about this time, in 1880, he expresses surprise at not hearing from America respecting certain drawings by Miss Kate Greenaway and himself, which had been sent across the Atlantic to be engraved on wood. “I wonder why?” he says—[The rest is reproduced opposite].

Caldecott was soon found out in his country home, his wide reputation as an illustrator bringing him ever-increasing work, some “not very profitable.”

[Pg 199]

At this time he was taxing his energies to the utmost, working a long morning always indoors, and afterwards making studies in the garden or in the country; the evening occupied by reading and correspondence.

The letters after this date refer to a period in Caldecott’s art which must be considered at a future time. Only two remembrances of his later years shall be recorded now; one of him at Kemsing,[Pg 202] seated in his old-fashioned garden on a fine summer’s afternoon (after hard work from nine till two) surrounded by his friends and four-footed playmates—a garden where the birds, and even the flowers, lived unrestrained.

The other and a later remembrance of Caldecott is at a gathering of friends in Victoria Street, Westminster, in January, 1885, when—to a good old English tune—the “lasses and lads,” out of his Picture Book, danced before him, and the fiddler, in the costume of the time, “played it wrong.”

It will be seen in the preceding pages that it was the privilege of the writer to know Caldecott intimately before he had made a name, when his heart and hands were free, so to speak; when he was untrammelled by much sense of responsibility, or by the necessity of keeping up a reputation, and when every day, almost, recorded some new experiment or achievement in his art. Let it be stated here that not at that time, nor ever[Pg 204] afterwards in the writer’s hearing, was a word said against Caldecott. With a somewhat wide and exceptional experience of the personality of artists, it can be said with truth that Caldecott was “a man of whom all spoke well.” His presence then, as in later years, seemed to dispel all jealousies, if they ever existed, and to scatter evil spirits if they ever approached him. No wonder—for was he not the very embodiment of sweetness, simple-mindedness, generosity, and honour?

From the sketch on page 1 of this book, made in the smoke of Manchester, to the “New Year’s Greeting” on p. 203, the same happy, joyous spirit is evident; and so, to those who knew him, he remained to the end.

As this memoir has to do with Caldecott’s earlier career, and particularly with his work in black and white, the artistic value of his illustrations in colour, especially in his Picture Books, can only be hinted at here.

Caldecott’s Picture Books are known all over the world; they have been widely discussed and criticised, and they form undoubtedly the best[Pg 205] monument to his memory. But it may be found that some of the best work he ever did (the work least open to criticism) was in 1874 and 1875, before these books were begun; and that the material here collected will aid in forming a better estimate of Caldecott as an artist.

In March, 1883 there appeared a little oblong Sketch Book with canvas cover, full of original and delightful illustrations, many in colour, engraved and printed by Edmund Evans. This book is not very widely known, but there are drawings in it of great personal interest, now that the artist’s hand is still. The Sketch Book suggests many thoughts and calls up many associations to those who knew him.

In 1883 he illustrated Æsop’s Fables with “Modern Instances” (referred to on page 94).

The kind of work that Caldecott liked best, and of which he would have been an artistic and delightful exponent had circumstances permitted, is indicated in the design at the head of the preface to this volume; it was drawn on brown paper, probably for a wood carving in relief, for the central[Pg 206] panel of a mantelpiece. This sketch is selected from several designs of a similar kind.

In purely journalistic work, for which his powers seemed eminently fitted, he was never at home, his heart was not in it. Neither on Punch nor on the Graphic newspaper, would he have engaged to work regularly. He would do anything on an emergency to aid a friend—or a foe, if he had known one—but neither health nor inclination led him in that direction. And yet Caldecott, of all contemporary artists, owed his wide popularity to the wood engraver, to the maker of colour blocks, and to the printing press. No artist before him had such chances of dispersing facsimiles of daintily coloured illustrations over the world. All this must be considered when his place in the century of artists is written.

Mr. Clough touches a true note in the following (from the Manchester Quarterly):—

“If the art, tender and true as it is, be not of the highest, yet the artist is expressed in his work as perhaps few others have been. Nothing to be regretted—all of the clearest—an open-air, pure life—a clean soul. Wholesome as the England he loved so well. Manly, tolerant, and patient under suffering. None of the[Pg 207] friends he made did he let go. No envy, malice, or uncharitableness spoiled him; no social flattery or fashionable success, made him forget those he had known in the early years.”

Speaking generally of his friend Caldecott, whom he had known intimately in later years, Mr. Locker-Lampson (to whom we are indebted for the letters and sketches on pages 191, 192, and 199), writes:—

“It seems to me that Caldecott’s art was of a quality that appears about once in a century. It had delightful characteristics most happily blended. He had a delicate fancy, and his humour was as racy as it was refined. He had a keen sense of beauty, and, to sum up all, he had charm. His old-world youths and maidens are perfect. The men are so simple and so manly, the maidens are so modest and so trustful: The latter remind one of the country girl in that quaint old ballad,

“Poor Caldecott! His friends were much attached to him. He had feelings, and ideas, and manners, which made him welcome in any society; but alas, all was trammelled, not obscured, by deplorably bad health.”

. . .

In the history of the century, the best and purest books and the brightest pages ever placed before children will be recorded between 1878 and 1885; and no words would seem more in touch with the[Pg 210] lives and aims of these lamented artists than a concluding sentence in Jackanapes, that—their works are “a heritage of heroic example and noble obligation.”

The grace and beauty, and wealth of imagination in Caldecott’s work,—conspicuous to the end,—form a monument which few men in the history of illustrative art have raised for themselves.

. . .

Caldecott’s Picture Books.

| THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT JOHN GILPIN |

} | 1878 |

| ELEGY ON A MAD DOG THE BABES IN THE WOOD |

} | 1879 |

| THREE JOVIAL HUNTSMEN SING A SONG OF SIXPENCE |

} | 1880 |

| THE QUEEN OF HEARTS THE FARMER’S BOY |

} | 1881 |

| THE MILKMAID HEY-DIDDLE-DIDDLE, THE Cat and the Fiddle; and Baby Bunting |

} | 1882 |

| THE FOX JUMPS OVER THE Parson’s Gate A FROG HE WOULD A-Wooing Go |

} | 1883 |

| COME, LASSES AND LADS RIDE A COCK HORSE TO BANBURY CROSS; and A Farmer went Trotting upon his Grey Mare |

} | 1884 |

| MRS. MARY BLAIZE THE GREAT PANJANDRUM HIMSELF |

} | 1885 |

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.