Alchemy

Magical Plants.

In remote ages, the poisonous or medicinal properties of plants were secrets learnt by the most intelligent and observant members of pastoral and nomadic tribes and clans; and the possessor of these secrets became often both medicine-man and priest, reserving to himself as much as possible the knowledge he had acquired of herbs and their uses, and particularly of those that would produce stupor, delirium, and madness; for by these means he could produce in himself and others many startling and weird manifestations, which the ignorance of his fellows would cause them to attribute to Divine or supernatural causes. The Zuckungen, or convulsions, ecstacies, temporary madness, and ravings, that formerly played so important a part in the oracular and sacerdotal ceremonies, and which survive even at the present day, had their origin in the tricks played by the ancient medicine-man in order to retain his influence over his superstitious brethren. The exciting and soporific properties of certain herbs and plants, and the peculiar phenomena which, in skilful hands, they could be made to produce in the victim, were well known to the ancient seers and priests, and so were easily foretold; while the symptoms and effects could be varied accordingly as the plants were dried, powdered, dissolved in water, eaten freshly gathered, or burnt as incense on the altars. The subtle powers of opiates obtained from certain plants were among the secrets carefully preserved by the magi and priests.

According to Prosper Alpinus, dreams of paradise and celestial visions were produced among the Egyptians by the use of Opium; and Kaempfer relates that after having partaken of an opiate in Persia, he fell into an ecstatic state, in which he conceived himself to be flying in the air beyond the clouds, and associating with celestial beings.

From the juice of the Hemp, the Egyptians have for ages prepared an intoxicating extract, called Hashîsh, which is made up into balls of the size of a Chestnut. Having swallowed some of these, and thereby produced a species of intoxication, they experience ecstatic visions.

Among the Brahmins, the Soma, a sacred drink prepared from the pungent juice of the Asclepias acida, or Cyanchum viminale, was one of the means used to produce the ecstatic state. Soma juice was employed to complete the phrensied trances of the Indian Yogis or seers: it is said to have the effect of inducing the ecstatic state, in which the votary appears in spirit to soar beyond the terrestrial regions, to become united with Brahma, and to acquire universal lucidity (clairvoyance). Windischmann observes that in the remote past, the mystic Soma was taken as a holy act—a species of sacrament; and that, by this means, the soul of the communicant became united with Brahma. It is frequently said that even Parashpati partook of this celestial beverage, the essence, as it is called, of all nourishment. In the human sacrifices, the Soma-drink was prepared with magical ceremonies and incantations, by which means the virtues of the inferior and superior worlds were supposed to be incorporated with the potion.

John Weir speaks of a plant, growing on Mount Lebanon, which places those who taste it in a state of visionary ecstacy; and Gassendi relates that a fanatical shepherd in Provence prepared himself for the visionary and prophetic state by using Stramonium.

The Laurel was held specially sacred to Apollo, and the Pythia who delivered the answer of the god to those who consulted the famous oracle at Delphi, before becoming inspired, shook a Laurel-tree that grew close by, and sometimes ate the leaves with which she crowned herself. A Laurel-branch was thought to impart to prophets the faculty of seeing that which was obscure or hidden; and the tree was believed to possess the property of inducing sleep and visions. Among the ancients it was also thought useful in driving away spectres. Evelyn, remarking on the custom of prophets and soothsayers sleeping upon the boughs and branches of trees, or upon mattresses composed of their leaves, tells us that the Laurel and Agnus Castus were plants “which greatly composed the phansy, and did facilitate true visions, and that the first was specially efficacious to inspire a poetical fury.” According to Abulensis, he adds, “such a tradition there goes of Rebekah, the wife of Isaac, in imitation of her father-in-law.” And he thinks it probable that from that incident the Delphic Tripos, the Dodonæan Oracle in Epirus, and others of a similar description, took their origin. Probably, when introducing the Jewish fortune-tellers in his sixth satire, Juvenal alludes to the practice of soothsayers and sibyls sleeping on branches and leaves of trees, in the lines—

The Druids, besides being priests, prophets, and legislators, were also physicians; they were acquainted, too, with the means of producing trances and ecstacies, and as one of their chief medical appliances they made use of the Mistletoe, which they gathered at appointed times with certain solemn ceremonies, and considered it as a special gift of heaven. This plant grew on the Oak, the sacred tree of the Celts and Druids; it was held in the highest reverence, and both priests and people then regarded it as divine. To this day the Welsh call Pren-awr—the celestial tree—

The sacred Oak itself was thought to possess certain magical properties in evoking the spirit of prophecy: hence we find the altars of the Druids were often erected beneath some venerated Oak-tree in the sombre recesses of the sacred grove; and it was under the shadow of such trees that the ancient Germans offered up their holy sacrifices, and their inspired bards made their prophetic utterances. The Greeks had their prophetic Oaks that delivered the oracles of Jupiter in the sacred grove of Dodona—

The Arcadians attributed another magical power to the Oak, for they believed that by stirring water with an Oaken bough rain could be brought from the clouds.

The Russians are acquainted with a certain herb which they call Son-trava, or Dream Herb, which has been identified with the Pulsatilla patens. This plant is said to blossom in the month of April, and to put forth an azure-coloured flower; if this is placed under the pillow, it will induce dreams, and these dreams are said to be fulfilled. In England, a four-leaved Clover similarly treated will produce a like result.

Like the Grecian sorceresses, Medea and Circe, the Vedic magicians were acquainted with numerous plants which would produce love-philtres of the most powerful character, if not altogether irresistible. The favourite flowers among the Indians for their composition are the Mango, Champak, Jasmine, Lotus, and Asoka. According to Albertus Magnus, the most powerful flower for producing love is that which he calls Provinsa. The secret of this plant had been transmitted by the Chaldeans. The Greeks knew it as Vorax, the Latins as Proventalis or Provinsa; and it is probably the same plant now known to the Sicilians as the Pizzu’ngurdu, to which they attribute most subtle properties. Thus the chastest of women will become the victim of the most burning passion for the man who, after pounding the Pizzu’ngurdu, is able to administer it to her in any sort of food.

Satyrion was a favourite herb with magicians, sorceresses, Witches, and herbalists, who held it to be one of the most powerful incentives of amatory passions. Kircher relates the case of a youth who, whenever he visited a certain corner of his garden, became so inflamed with passionate longings, that, with the hope of obtaining relief, he mentioned the circumstance to a friend, who, upon examing the spot, found it overgrown with a species of Satyrion, the odour from which had the effect of producing amatory desires.

The Mandrake, Carrot, Cyclamen, Purslain (Aizoon), Valerian, Navel-wort (Umbilicus Veneris), Wild Poppy (Papaver Argemone), Anemone, Orchis odoratissima, O. cynosorchis, O. tragorchis, O. triorchis, and others of the same family, and Maidenhair Fern (Capillus Veneris) have all of them the property of inspiring love.

In Italy, Basil is considered potent to inspire love, and its scent is thought to engender sympathy. Maidens think that it will stop errant young men and cause them to love those from whose hands they accept a sprig. In England, in olden times, the leaves of the Periwinkle, when eaten by man and wife, were supposed to cause them to love one another. An old name appertaining to this plant was that of the “Sorcerer’s Violet,” which was given to it on account of its frequent use by wizards and quacks in the manufacture of their charms against the Evil Eye and malign spirits. The French knew it as the Violette des Sorciers, and the Italians as Centocchio, or Hundred Eyes.

In Poland, a plant called Troizicle, which has bluish leaves and red flowers, has the reputation of causing love and forgetfulness of the past, and of enabling him who employs it to go wherever he desires.

Helmontius speaks of a herb that when held in the palm of the hand until it grows warm, will rapidly acquire the power of detaining the hand of another until it not only grows warm, also, but the owner becomes inflamed with love. He states that by its use he inspired a dog with such love for himself, that he forsook a kind mistress to follow him, a stranger. This herb is said to be met with everywhere, but unfortunately the name is not given.

Cumin is thought to possess a mystical power of retention: hence it has found its way into many a love-philtre, as being able to ensure fidelity and constancy in love.

Among the plants and flowers to which the power of divination has been ascribed, and which are consulted for the most part by rustic maidens in affairs of the heart, are the Centaury, Bluet, or Horseknot, the Starwort, the Ox-eye Daisy, the Dandelion, Bachelor’s Buttons, the Primrose, the Rose, the Poppy, the Hypericum, the Orpine, the Yarrow, the Mugwort, the Thistle, the Knotweed, Plantain, the Stem of the Bracken Fern, Four-leaved and Two-leaved Clover, Even Ash-leaves, Bay or Bay-leaves, Laurel-leaves, Apples and Apple-pips, Nuts, Onions, Beans, Peascods, Corn, Maize, Hemp-seed, &c.

Albertus Magnus states that Valeria yields a certain juice of amity, efficacious in restoring peace between combatants; and that the herb Provinsa induces harmony between husband and wife. Gerarde, in his ‘Herbal,’ mentions a plant, called Concordia, which he says is Argentina, or Silver-weed (Potentilla anserina); and in Piedmont, at the present time, there grows a plant (Palma Christi), locally known as Concordia, which the peasantry use for matrimonial divinations. The root of the plant is said to be divided into two parts, each bearing a resemblance to the human hand, with five fingers: if these hands are found united, marriage is sure; but if separated, a rupture between the lovers is presaged. There is also, in Italy, a plant known as Discordia, likewise employed for love divinations. In this plant the male flowers are violet, the female white; the male and female flowers blossom almost always the one after the other—the male turns to the East, the female to the West.

In the Ukraine, there grows a plant called there Prikrit, which, if gathered between August 15th and October 1st, has the property of destroying calumnies spread abroad in order to hinder marriages. In England, the Baccharis, or Ploughman’s Spikenard, is reputed to be able to repel calumny. In Russia, a plant called Certagon, the Devil-chaser, is used to exorcise the devil, who is supposed to haunt the grief-stricken husband or wife whom death has robbed of the loved one. This grief-charming plant is also used to drive away fear from infants. The Sallow has many magical properties: no child can be born in safety where it is hung, and no spirit can depart in peace if its foliage be anywhere near.

The Zuñis, a tribe of Mexican Indians, hold in high veneration a certain magical plant called Té-na-tsa-li, which they aver grows only on one mountain in the West, and which produces flowers of many colours, the most beautiful in the world, whilst its roots and juices are a panacea for all injuries to the flesh of man.

The Indian Tulasi, or Sacred Basil (Ocimum sanctum) is pre-eminently a magical herb. By the Hindus it is regarded as a plant of the utmost sanctity, which protects those that cultivate it from all misfortunes, guards them from diseases and injuries, and ensures healthy children. In Burmah, the Eugenia is endowed with similar magical properties, and is regarded by the Burmese with especial reverence.

The Onion, if suspended in a room, possesses the magical powers of attracting and absorbing maladies that would otherwise attack the inmates.

In Peru, there is said to grow a wonderful tree called Theomat. If a branch be placed in the hand of a sick person, and he forthwith shows gladness, it is a sign that he will at length recover; but if he shows sadness and no sign of joy, that is held to be a certain sign of approaching death.

In England, the withering of Bay-leaves has long been considered ominous of death: thus Shakspeare writes—

The smoke of the green branches of the Juniper was the incense offered by the ancients to the infernal deities, whilst its berries were burnt at funerals to keep off evil spirits.

The Peony drives away tempests and dispels enchantments. The St. John’s Wort (called of old Fuga dæmonum) is a preservative against tempests, thunder, and evil spirits, and possesses other magical properties which are duly enumerated in another place.

The Rowan-tree of all others is gifted with the powers of magic, and is held to be a charm against the Evil Eye, witchcraft, and unholy spells. The Elder, the Thorn, the Hazel, and the Holly, in a similar manner, possess certain properties which entitle them to be classed as magical plants. Garlic is employed by the Greeks, Turks, Chinese, and Japanese, as a safeguard against the dire influences of the Evil Eye.

The extraordinary attributes of the Fern-seed are duly enumerated in Part II., under the head of Fern, and can be there studied by all who are desirous of investigating its magic powers.

The Clover, if it has four leaves, is a magical plant, enabling him who carries it on his person to be successful at play, and have the power of detecting the approach of malignant spirits. If placed in the shoe of a lover, the four-leaved Clover will ensure his safe return to the arms and embraces of his sweetheart.

The Mandrake is one of the most celebrated of magical plants, but for an enumeration of its manifold mystic powers readers must be referred to the description given in Part II., under the head of Mandrake. This plant was formerly called Circeium, a name derived from Circe, the celebrated enchantress. The Germans call it Zauberwurzel (Sorcerer’s root), and the young peasant girls of the Fatherland often wear bits of the plant as love charms.

The marshes of China are said to produce a certain fruit which the natives call Peci. If any one puts with this fruit a copper coin into his mouth, he can diminish it with no less certainty than the fruit itself, and reduce it to an eatable pulp.

In France, Piedmont, and Switzerland, the country-people tell of a certain Herb of Oblivion which produces loss of memory in anyone putting his foot upon it. This herb also causes wayfarers to lose their way, through the unfortunates forgetting the aspects of the country, even although they were quite familiar to them before treading on the Herb of Forgetfulness. Of a somewhat similar nature must have been the fruit of the Lotos-tree, which caused the heroes of the Odyssey to forget their native country.

King Solomon, whose books on Magic King Hezekiah destroyed lest their contents should do harm, ascribed great magical powers to a root which he called Baharas (or Baara). Josephus, in his History of the Jewish Wars, states that this wonderful root is to be found in the region of Judæa. It is like a flame in colour, and in the evening appears like a glittering light; but upon anyone approaching it with the idea of pulling it up, it appears to fly or dart away, and will avoid its pursuer until it be sprinkled either with menstrual blood or lotium femininum.

“The Mandrake’s charnel leaves at night”

possess the same characteristic of shining through the gloom, and, on that account, the Arabians call it the Devil’s Candle.

The ancients knew a certain herb called Nyctilopa, which had the property of shining from afar at night: this same herb was also known as Nyctegredum or Chenomychon, and geese were so averse to it, that upon first spying it they would take to instant flight. Perhaps this is the same plant as the Johanniswurzel or Springwort (Euphorbia lathyris), which the peasants of Oberpfalz believe can only be found among the Fern on St. John’s Night, and which is stated to be of a yellow colour, and to shine at night as brightly as a candle. Like the Will-o’-the-Wisp, the Johanniswurzel eludes the grasp of man by darting and frisking about.

Several plants are credited with possessing the power of preservation from thunder and lightning. Pliny mentions the Vibro, which he calls Herba Britannica, as a plant which, if picked before the first thunderblast of a storm was heard, was deemed a safeguard against lightning. In the Netherlands, the St. John’s Wort, gathered before sunrise, is credited with protective powers against lightning. In Westphalia, the Donnerkraut (the English Orpine, or Live-long) is kept in houses as a preservative from thunder. In England, the Bay is considered a protection from lightning and thunder; the Beech was long thought to be a safeguard against the effects of lightning; and Houseleek or Stonecrop, if grown upon a roof, is still regarded as protecting the house from being struck by lightning. The Gnaphalium, an Everlasting-flower, is gathered on the Continent, on Ascension Day, and suspended over doorways, to fulfil the same function. In Wales, the Stonecrop is cultivated on the roof to keep off disease.

The Selago, or Golden Herb of the Druids, imparted to the priestess who pressed it with her foot, the knowledge of the language of animals and birds. If she touched it with iron, the sky grew dark, and a misfortune befell the world.

The old magicians were supposed to have been acquainted with certain plants and herbs from which gold could be extracted or produced. One of these was the Sorb-tree, which was particularly esteemed for its invaluable powers; another was a herb on Mount Libanus, which was said to communicate a golden hue to the teeth of the goats and other animals that grazed upon it. Niebuhr thinks this may be the herb which the Eastern alchymists employed as a means of making gold. Father Dundini noticed that the animals living on Mount Ida ate a certain herb that imparted a golden hue to the teeth, and which he considered proceeded from the mines underground. It was an old belief in Germany, by the shores of the Danube, and in Hungary, that the tendrils and leaves of the Vines were plated with gold at certain periods, and that when this was the case, it was a sure sign that gold lay hidden somewhere near.

Plutarch speaks of a magical herb called Zaclon, which, when bruised and thrown into wine, would at once change it into water.

Some few plants, like the well-known Sesame of the ‘Arabian Nights,’ are credited with the power of opening doors and obtaining an entry into subterranean caverns and mountain sides. In Germany, there is a very favourite legend of a certain blue Luck-flower which gains for its fortunate finder access to the hidden recesses of a mountain, where untold riches lie heaped before his astonished eyes. Hastily filling his pockets with gold, silver, and gems, he heeds not the presence of a dwarf or Fairy, who, as he unknowingly drops the Luck-flower whilst leaving the treasure-house, cries “Forget not the best of all.” Thinking only of the wealth he has pocketed, he unheedingly passes through the portal of the treasure cave, only just in time to save himself from being crushed by the descending door, which closes with an ominous clang, and shuts in for ever the Luck-flower, which can alone open the cave again.

In Russia, a certain herb, which has the power of opening, is known as the Rasriv-trava. The peasants recognise it in this manner: they cut a good deal of grass about the spot where the Rasriv-trava is thought to grow, and throw the whole of it into the river; thereupon this magic plant will not only remain on the surface of the water, but it will float against the current. The herb, however, is extraordinarily rare, and can only be found by one who also possesses the herb Plakun and the Fern Paporotnik. The Fern, like the Hazel, discovers treasures, and therefore possesses the power of opening said to belong to the Rasriv-trava, but the latter is the only plant that can open the locks of subterranean entrances to the infernal regions, which are always guarded by demons. It also has the special property of being able to reduce to powder any metal whatsoever.

The Primrose is in Germany regarded as a Schlüsselblume, or Key-flower, and is supposed to provide the means of obtaining ingress to the many legendary treasure-caverns and subterranean passages under hill and mountain sides dating back from the remote times when the Goddess Bertha was wont to entice children to enter her enchanted halls by offering them pale Primroses.

The Mistletoe, in addition to its miraculous medicinal virtues, possesses the power of opening all locks; and a similar property is by some ascribed to Artemisia, the Mandrake, and the Vervain.

The Moonwort, or Lesser Lunary (Botrychium Lunaria)—the Martagon of ancient wizards, the Lunaria minor of the alchymists—will open the locks of doors if placed in proper fashion in the keyhole. It is, according to some authorities, the Sferracavallo of the Italians, and is gifted with the power of unshoeing horses whilst at pasture.

Grimm is of opinion that the Sferracavallo is the Euphorbia lathyris, the mystic Spring-wort, which, like the Luck-flower, possesses the wondrous power of opening hidden doors, rocks, and secret entrances to treasure caves, but which is only to be obtained through the medium of a green or black woodpecker under conditions which will be found duly recorded in Part II., under the head of Springwort.

The Mouse-ear is called Herba clavorum because it prevents the blacksmith from hurting horses when he is shoeing them.

Magic Wands and Divining Rods.

At so remote a period as the Vedic age we find allusions to magic wands or rods. In the Vedas, the Hindu finds instructions for cutting the mystic Sami branch and the Arani. This operation was to be performed so that the Eastern and Western sun shone through the fork of the rod, or it would prove of no avail. The Chinese still abide by these venerable instructions in the cutting of their magic wands, which are usually cut from the Peach or some other fruit tree on the night preceding the new year, which always commences with the first new moon after the Winter solstice. The employment of magic wands and staffs was in vogue among the Chaldæans and Egyptians, who imparted the knowledge of this system of divination to the Hebrews dwelling among them. Thus we find the prophet Hosea saying, “My people ask counsel at their stocks, and their staff declareth unto them.” Rhabdomancy, or divination by means of a rod, was practised by the ancient Greeks and Romans, and the art was known in England at the time of Agricola, though now it is almost forgotten. In China and Eastern lands, the art still flourishes, and various kinds of plants and trees are employed; the principal being, however, the Hazel, Osier, and Blackthorn. The Druids were accustomed to cut their divining-rods from the Apple-tree. In competent hands, the Golden Rod is said to point to hidden springs of water, as well as to hidden treasures of gold and silver.

In Cornwall, the divining-rod is still employed by miners to discover the presence of mineral wealth; in Lancashire and Cumberland, the belief in the powers of the magic wand is widely spread; and in Wiltshire, it is used for detecting water. The Virgula divinatoria is also frequently in requisition both in Italy and France. Experts will tell you that, in order to ensure success, certain mystic rites must be performed at the cutting of the rod: this must be done after sunset and before sunrise, and only on certain special nights, among which are those of Good Friday, Epiphany, Shrove-Tuesday, and St. John’s Day, the first night of a new moon, or that preceding it. In cutting the divining-rod, the operator must face the East, so that it shall be one which catches the first rays of the morning sun, or it will be valueless. These conditions, it will be found, are similar to those contained in the Hindu Vedas, and still enforced by the Chinese. Some English experts are of opinion that a twig of an Apple-tree may be used as successfully as a Hazel wand—but it must be of twelve months’ growth. The seventh son of a seventh son is considered to be the most fitting person to use the rod. In operating, the small ends, being crooked, are to be held in the hands in a position flat or parallel to the horizon, and the upper part at an elevation having an angle to it of about seventy degrees. The rod must be grasped strongly and steadily, and then the operator walks over the ground: when he crosses a lode, its bending is supposed to indicate the presence thereof. According to Vallemont, the author of a treatise on the divining-rod, published towards the end of the seventeenth century, its use was not merely confined to indicate metal or water, but it was also employed in tracking criminals; and an extraordinary story is told of a Frenchman who, guided by his rod, “pursued a murderer, by land, for a distance exceeding forty-five leagues, besides thirty leagues more by water.”

From an article in the ‘Quarterly Review,’ No. 44, the statements in which were vouched by the Editor, it would seem that a Lady Noel possessed the faculty of using the divining-rod. In operating, this lady “took a thin forked Hazel-twig, about sixteen inches long, and held it by the end, the joint pointing downwards. When she came to the place where the water was under the ground, the twig immediately bent; and the motion was more or less rapid as she approached or withdrew from the spring. When just over it, the twig turned so quick as to snap, breaking near the fingers, which, by pressing it, were indented and heated, and almost blistered; a degree of agitation was also visible in her face. The exercise of the faculty is independent of any volition.”

In Germany, the divining-rod is often called the wishing-rod, and as it is by preference cut from the Blackthorn, that tree is known also as the Wishing Thorn. In Prussia, the Hazel rod must be cut in Spring to have its magical qualities thoroughly developed. When the first thunderstorm is seen to be approaching, a cross is made with the rod over every heap of grain, in order that the Corn so distinguished may keep good for many a month. In Bohemia, the magic rod is thought to cure fever; it is necessary, however, when purchasing one, not to raise an objection to the price. In Ireland, if anyone dreams of buried money, there is a prescribed formula to be employed when digging for it—a portion of which is the marking upon a Hazel wand three crosses, and the recital of certain words, of a blasphemous character, over it.

Sir Thomas Browne tells us that, in his time, the divining-rod was called Moses’ Rod; and he thinks, with Agricola, that this rod is of Pagan origin:—“The ground whereof were the magical rods in poets, that of Pallas in Homer, that of Mercury that charmed Argus, and that of Circe which transformed the followers of Ulysses. Too boldly usurping the name of Moses’ Rod, from which notwithstanding, and that of Aaron, were probably occasioned the fables of all the rest. For that of Moses must needs be famous, unto the Egyptians, and that of Aaron unto many other nations as being preserved in the Ark until the destruction of the Temple built by Solomon.” The Rabbis tell us that the rod of Moses was, originally, carved by Adam out of a tree which grew in the Garden of Eden; that Noah, who took it into the Ark with him, bequeathed it to Shem; that it descended to Abraham; that Isaac gave it to Jacob; that, during his sojourn in Egypt, he gave it to Joseph; and that finally it became the property of Moses.

Fabulous, Wondrous, and Miraculous Plants.

We have seen how, among the ancient races of the earth, traditions existed which connected the origin of man with certain trees. In the Bundehesh, man is represented as having first appeared on earth under the form of the plant Reiva (Rheum ribes). In the Iranian account of man’s creation, the primal couple are stated to have first grown up as a single tree, and at maturity to have been separated and endowed with a distinct existence by Ormuzd. In the Scandinavian Edda, men are represented as having sprung from the Ash and Poplar. The Greeks traced the origin of the human race to the maternal Ash; and the Romans regarded the Oak as the progenitor of all mankind. The conception of human trees was present in the mind of the Prophet Isaiah, when he predicted that from the stem of Jesse should come forth a rod, and from his roots, a branch. The same idea is preserved in the genealogical trees of modern heraldry; and the marked analogy between man and trees has doubtless given rise to the custom of planting trees at the birth of children. The old Romans were wont to plant a tree at the birth of a son, and to judge of the prosperity of the child by the growth and thriving of the tree. It is said in the life of Virgil, that the Poplar planted at his birth flourished exceedingly, and far outstripped all its contemporaries. De Gubernatis records that, as a rule, in Germany, they plant Apple-trees for boys, and Pear-trees for girls. In Polynesia, at the birth of an infant, a Cocoa-nut tree is planted, the nodes of which are supposed to indicate the number of years promised to the little stranger.

According to a legend that Hamilton found current in Central India, the Khatties had this strange origin. When the five sons of Pându (the heroes whose exploits are told in the Mahâbhârata) had become simple tenders of flocks, Karna, their illegitimate brother, wishing to deprive them of these their last resource, prayed the gods to assist him: then he struck the earth with his staff, which was fashioned from the branch of a tree. The staff instantly opened, and out of it sprang a man, who said that his name was Khat, a word which signifies “begotten of wood.” Karna employed this tree-man to steal the coveted cattle, and the Khatties claim to be descended from this strange forefather.

The traditions of trees that brought forth human beings, and of trees that were in themselves partly human, are current among most of the Aryan and Semitic races, and are also to be found among the Sioux Indians. These traditions (which have been previously noticed in Chapter VII.) have probably given rise to others, which represent certain trees as bearing for fruit human beings and the members of human beings.

In the fourteenth century, an Italian voyager, Odoricus du Frioul, on arriving at Malabar, heard the natives speaking of trees which, instead of fruit, bore men and women: these creatures were scarcely a yard high, and their nether extremities were attached to the tree’s trunk, like branches. Their bodies were fresh and radiant when the wind blew, but on its dropping, they became gradually withered and dried up.

In the first book of the Mahâbhârata, reference is made, in the legend of Garuda, to an enormous Indian Fig-tree (Ficus religiosa), from the branches of which are suspended certain devotees of dwarfed proportions, called Vâlakhilyas.

Among the Arabs, there exists a tradition of an island in the Southern Ocean called Wak-Wak, which is so-named because certain trees growing thereon produce fruit having the form of a human head, which cries Wak! Wak!

Among the Chinese, the myth of men being descended from trees is reversed, for we find a legend current in the Flowery Land that, in the beginning, the herbs and plants sprang from the hairs of a cosmic giant.

The Chinese, however, preserve the tradition of a certain lake by whose margin grew great quantities of trees, the leaves of which when developed became changed into birds. In India, similar trees are referred to in many of the popular tales: thus, in “The Rose of Bakavali” mention is made of a garden of Pomegranate-trees, the fruit of which resembled earthenware vases. When these were plucked and opened, out hopped birds of beautiful plumage, which immediately flew away.

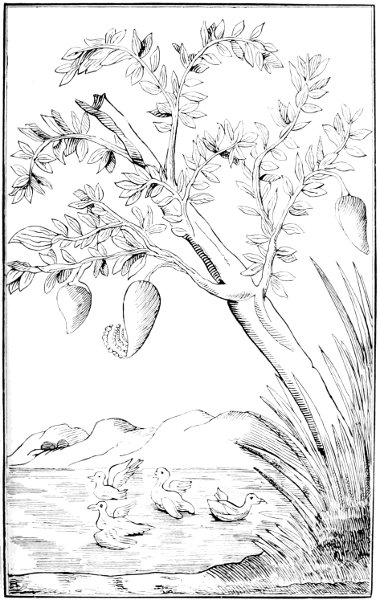

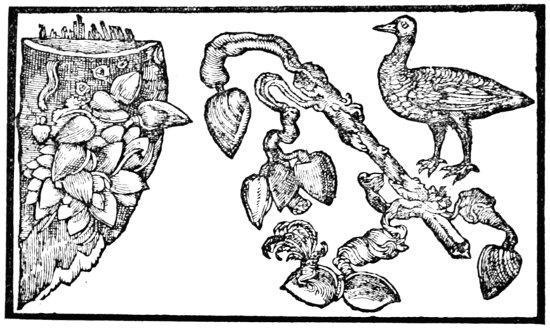

Pope Pius II., in his work on Asia and Europe, published towards the end of the fifteenth century, states that in Scotland there grew on the banks of a river a tree which produced fruits resembling ducks; these fruits, when matured, fell either on the river bank or into the water: those which fell on the ground perished instantly; those which fell into the water became turned at once into ducks, acquired plumage, and then flew off. His Holiness remarks that he had been unable to obtain any proof of this wondrous tree existing in Scotland, but that it was to be found growing in the Orkney Isles.

As early as the thirteenth century, Albertus Magnus expressed his disbelief in the stories of birds propagated from trees, yet there were not wanting writers who professed to have been eye-witnesses of the marvels they recounted respecting Bernicle or Claik Geese. Some of these witnesses, however, asserted that the birds grew on living trees, while others traced them to timber rotted in the sea, or boughs of trees which had fallen therein. Boëce, who favoured the latter theory, writes that “because the rude and ignorant people saw oft-times the fruit that fell off the trees (which stood near the sea) converted within a short time into geese, they believed that yir-geese grew upon the trees, hanging by their nebbis [bills] such like as Apples and other fruits hangs by their stalks, but their opinion is nought to be sustained. For as soon as their Apples or fruit falls off the tree into the sea-flood, they grow first worm-eaten, and by short process of time are altered into geese.” Munster, in his ‘Cosmographie,’ remembers that in Scotland “are found trees which produce fruit rolled up in leaves, and this, in due time, falling into water, which it overhangs, is converted into a living bird, and hence the tree is called the Goose-tree. The same tree grows in the island of Pomona. Lest you should imagine that this is a fiction devised by modern writers, I may mention that all cosmographists, particularly Saxo Grammaticus, take notice of this tree.” Prof. Rennie says that Montbeillard seems inclined to derive the name of Pomona from its being the orchard of these goose-bearing trees. Fulgosus depicts the trees themselves as resembling Willows, “as those who had seen them in Ireland and Scotland” had informed him. To these particulars, Bauhin adds that, if the leaves of this tree fall upon the land, they become birds; but if into the water, then they are transmuted into fishes.

Maundevile speaks of the Barnacle-tree as a thing known and proved in his time. He tells us, in his book, that he narrated to the somewhat sceptical inhabitants of Caldilhe how that “in oure contre weren trees that beren a fruyt that becomen briddes fleiynge: and thei that fallen on the erthe dyen anon: and thei ben right gode to mannes mete.”

Aldrovandus gives a woodcut of these trees, in which the foliage resembles that of Myrtles, while the strange fruit is large and heart-shaped.

Gerarde also gives a figure of what he calls the “Goose-tree, Barnacle-tree, or the tree bearing geese,” a reproduction of which is annexed. And although he speaks of the goose as springing from decayed wood, &c., the very fact of his introducing the tree into the catalogue of his ‘Herbal,’ shows that he was, at least, divided between the above-named opinions. “What our eyes have seen,” he says, “and what our hands have touched, we shall declare. There is a small island in Lancashire, called the Pile of Foulders, wherein are found broken pieces of old ships, some whereof have been thrown thither by shipwracke, and also the trunks and bodies, with the branches of old and rotten trees cast up there likewise; whereon is found a certain spume or froth, that in time breedeth unto certaine shells, in shape like to those of the muskle, but sharper pointed, and of a whitish colour, wherein is contained a thing in forme like a lace of silke finely woven, as it were, together, of a whitish colour; one end whereof is fastned unto the inside of the shell, even as the fish of oisters and muskles are; the other end is made fast unto the belly of a rude mass, or lumpe, which, in time, commeth to the shape and forme of a bird. When it is perfectly formed, the shell gapeth open, and the first thing that appeareth is the foresaid lace or string; next come the legs of the bird hanging out, and as it groweth greater it openeth the shell by degrees, till at length it is all come forth, and hangeth onely by the bill; in short space after it commeth to full maturitie, and falleth into the sea, where it gathereth feathers, and groweth to a fowle bigger than a mallard and lesser than a goose, having blacke legs and bill or beake, and feathers blacke and white, spotted in such manner as is our magpie; called in some places a pie-annet, which the people of Lancashire call by no other name than tree-goose; which place aforesaid, and all those parts adjoyning, do so much abound therewith, that one of the best is bought for threepence. For the truth hereof, if any doubt, may it please them to repaire unto me, and I shall satisfie them by the testimonie of good witnesses.

The Goose Tree. From Gerarde’s Herbal.

Martin assures us that he had seen many of these fowls in the shells, sticking to the trees by the bill, but acknowledges that he had never descried any of them with life upon the tree, though the natives [of the Orkney Isles] had seen them move in the heat of the sun.

In the ‘Cosmographiæ of Albioun,’ Boëce (to whom we have before referred) considered the nature of the seas acting on old wood more relevant to the creation of barnacle or claik geese than anything else. “For,” he says, “all trees that are cassin into the seas, by process of time appears at first worm-eaten, and in the small holes or bores thereof grows small worms. First they show their head and neck, and last of all they show their feet and wings. Finally, when they are come to the just measure and quantity of geese, they fly in the air, as other fowls wont, as was notably proven in the year of God one thousand four hundred and eighty in the sight of many people beside the castle of Pitslego.” He then goes on to describe how a tree having been cast up by the sea, and split by saws, was found full of these geese, in different stages of their growth, some being “perfect shapen fowls;” and how the people, “having ylk day this tree in more admiration,” at length deposited it in the kirk of St. Andrew’s, near Tyre.”

Among the more uninformed of the Scotch peasantry, there still exists a belief that the Soland goose, or gannet, and not the bernicle, grows by the bill on the cliffs of Bass, of Ailsa, and of St. Kilda.

Giraldus traces the origin of these birds to the gelatinous drops of turpentine which appear on the branches of Fir-trees.

“A tree that bears oysters is a very extraordinary thing,” remarks Bishop Fleetwood in his ‘Curiosities of Agriculture and Gardening’ (1707), “but the Dominican Du Tertre, in his Natural History of Antego, assures us that he saw, at Guadaloupa, oysters growing on the branches of trees. These are his very words. The oysters are not larger than the little English oysters, that is to say, about the size of a crown piece. They stick to the branches that hang in the water of a tree called Paretuvier. No doubt the seed of the oysters, which is shed in the tree when they spawn, cleaves to those branches, so that the oysters form themselves there, and grow bigger in process of time, and by their weight bend down the branches into the sea, and then are refreshed twice a day by the flux and reflux of it.”

The Oyster-bearing Tree, however, is not the only marvel of which the good Bishop has left a record: he tells us that near the island Cimbalon there lies another, where grows a tree whose leaves, as they fall off, change into animals: they are no sooner on the ground, than they begin to walk like a hen, upon two little legs. Pigafetta says that he kept one of these leaves eight days in a porringer; that it took itself to walking as soon as he touched it; and that it lived only upon the air. Scaliger, speaking of these very leaves, remarks, as though he had been an eye-witness, that they walk, and march away without further ado if anyone attempts to touch them. Bauhin, after describing these wonderful leaves as being very like Mulberry-leaves, but with two short and pointed feet on each side, remarks upon the great prodigy of the leaf of a tree being changed into an animal, obtaining sense, and being capable of progressive motion.

TO FACE PAGE 121.]

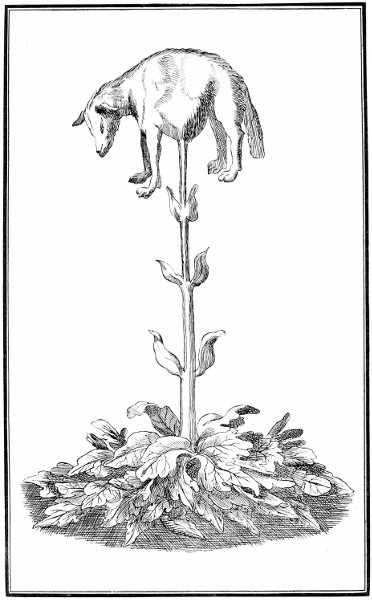

The Barometz, or Vegetable Lamb.

From Zahn’s ‘Speculæ Physico-Mathematico-Historicæ.’

Kircher records that in his time a tree was said to exist in Chili, the leaves of which produced worms; upon arriving at maturity, these worms crawled to the edge of the leaf, and thence fell to the earth, where after a time they became changed into serpents, which over-ran the whole land. Kircher endeavours to explain this story of the serpent-bearing tree by giving, as a reason for the phenomenon, that the tree attached to itself, through its roots, moisture pregnant with the seed of serpents. Through the action of the sun’s rays, and the moisture of the tree, this serpent-spawn degenerates into worms, which by contact with the earth become converted into living serpents.

The same authority states that in the Molucca islands, but more particularly in Ternate, not far from the castle of the same name, there grew a plant which he describes as having small leaves. To this plant the natives gave the name of Catopa, because when its leaves fall off they at once become changed into butterflies.

Doctor Darwin, in his botanical poem called ‘The Loves of the Plants,’ thus apostrophises an extraordinary animal-bearing plant:—

In the curious frontispiece to Parkinson’s ‘Paradisus,’ which will be found reproduced at the commencement of this work, it will be noticed that the Barometz, or Vegetable Lamb, is represented as one of the plants growing in Eden. In Zahn’s Speculæ Physico-Mathematico-Historicæ (1696) is given a figure of this plant, accompanied by a description, of which the following is a translation:—

“Very wonderful is the Tartarian shrub or plant which the natives call Boromez, i.e., Lamb. It grows like a lamb to about the height of three feet. It resembles a lamb in feet, in hoofs, in ears, and in the whole head, save the horns. For horns, it possesses tufts of hair, resembling a horn in appearance. It is covered with the thinnest bark, which is taken off and used by the inhabitants for the protection of their heads. They say that the inner pulp resembles lobster-flesh, and that blood flows from it when it is wounded. Its root projects and rises to the umbilicus. What renders the wonder more remarkable is the fact that, when the Boromez is surrounded by abundant herbage, it lives as long as a lamb, in pleasant pastures; but when they become exhausted, it wastes away and perishes. It is said that wolves have a liking for it, while other carnivorous animals have not.”

Scaliger, in his Exotericæ Exercitationes, gives a similar description, adding that it is not the fruit, the Melon, but the whole plant, that resembles a lamb. This does not tally with the account given by Odorico da Pordenone, an Indian traveller, who, before the Barometz had been heard of in Europe, appears to have been informed that a plant grew on some island in the Caspian Sea which bore Melon-like fruit resembling a lamb; and this tree is described and figured by Sir John Maundevile, who, in speaking of the countries and isles beyond Cathay, says that when travelling towards Bacharye “men passen be a Kyngdom that men clepen Caldilhe; that is a fulle fair Contree. And there growethe a maner of fruyt as thoughe it waren Gowrdes; and whan thei ben rype, men kutten hem a to, and men fynden with inne, a lytylle Best, in flessche, in bon, and blode, as though it were a lytylle Lomb, with outen wolle. And men eten bothe the Frut and the Best; and that is a gret marveylle. Of that Frute I have eten; alle thoughe it were wonderfulle; but that I knowe wel that God is marveyllous in his werkes.”

The Lamb Tree. From Maundevile’s Travels.

Maundevile, who in his book has left a record of so many marvellous things which he either saw or was told of during his Eastern travels, mentions a certain Indian island in the land of Prester John, where grew wild trees which produced Apples of such potent virtue that the islanders lived by the mere smell of them: moreover if they went on a journey, the men “beren the Apples with hem: for yif thei hadde lost the savour of the Apples thei scholde dyen anon.” In another island in the same country, Sir John was told were the Trees of the Sun and of the Moon that spake to King Alexander, and warned him of his death. Moreover, it was commonly reported that “the folk that kepen the trees, and eten of the frute and of the bawme that growethe there, lyven wel 400 yere or 500 yere, be vertue of the fruit and of the bawme.” In Egypt the old traveller heard of the Apple-tree of Adam, “that hav a byte at on of the sydes;” there also he saw Pharaoh’s Figs, which grew upon trees without leaves; and there also he tells us are gardens that have trees and herbs in them which bear fruit seven times in the year.

One of the most celebrated of fabulous trees is that which grew in the garden of the Hesperides, and produced the golden Apples which Hercules, with the assistance of Atlas, was able to carry off. Another classic tree is that bearing the golden branch of Virgil, which is by some identified with the Mistletoe. Among other celebrated mythical trees may be named the prophetic Oaks of the Dodonæan grove; the Singing Tree of the ‘Arabian Nights,’ every leaf of which was a mouth and joined in concert; and the Poet’s Tree referred to by Moore, in ‘Lalla Rookh,’ which grows over the tomb of Tan-Sein, a musician of incomparable skill at the court of Akbar, and of which it is said that whoever chews a leaf will have extraordinary melody of voice.

Wondrous Plants.

In Bishop Fleetwood’s curious work, to which reference has already been made, we find many extraordinary trees and plants described, some of which are perhaps worthy of a brief notice. He tells us of a wonderful metal-sapped tree known as the Mesonsidereos, which grows in Java, and even there is very scarce. Instead of pith, this tree has an iron wire that comes out of the root, and rises to the top of the tree. “But the best of all is, that whoever carries about him a piece of this ferruginous pith is invulnerable to any sword or iron whatever.” In Hirnaim de Typho this tree is said to produce fruit impenetrable by iron.

There are some trees that must have fire to nourish them. Methodius states that he saw on the top of the mountain Gheschidago (the Olympus of the ancients), near the city of Bursa, in Natolia, a lofty tree, whose roots were spread amidst the fire that issues from the vents of the earth; but whose leafy and luxuriant boughs spread their shade around, in scorn of the flames in the midst of which it grew.

This vegetable salamander finds its equal in a plant described by Nieuhoff as growing in rocky and stony places in the kingdom of Tanju, in Tartary. This extraordinary plant cannot be either ignited or consumed by fire; for although it becomes hot, and on account of the heat becomes glowing red in the fire, yet so soon as heat is removed, it grows cold, and regains its former appearance: in water, however, this plant is wont to become quite putrid.

Of a nature somewhat akin to these fire-loving plants must be the Japanese Palm, described by A. Montanus. This tree is said to shun moisture to such an extent, that if its trunk be in the least wet, it at once pines away and perishes as though it had been poisoned. However, if this arid tree be taken up by the roots, throughly dried in the sun, and re-planted with sand and iron filings around it, it will once more flourish, and become covered with new branches and leaves, provided that so soon as it has been re-planted, the old leaves are cut off with an iron instrument and fastened to the trunk.

The Bishop remarks that “one of the most wonderful plants is that which so mollifies the bones, that when we have eaten of it we cannot stand upon our legs. An ox who has tasted of it cannot go; his bones grow so pliant, that you may bend his legs like a twig of Ozier. The remedy is to make him swallow some of the bones of an animal who died from eating of that herb: ’tis certain death, and cannot be otherwise, for the teeth grow soft immediately, and ’tis impossible even to eat again.” “There is a plant that produces a totally opposite effect. It hardens the bones to a wondrous degree. A man who has chewed some of it, will have his teeth so hard as to be able to reduce flints and pebbles into impalpable powder.”

Maundevile describes some wonderful Balm-trees that in his time grew near Cairo, in a field wherein were seven wells “that oure Lord Jesu Christ made with on of His feet, whan He wente to pleyen with other children.” The balm obtained from these trees was considered so precious, that no one but the appointed tenders was allowed to approach them. Christians alone were permitted to till the ground in which they grew, as if Saracens were employed, the trees would not yield; and moreover it was necessary that men should “kutten the braunches with a scharp flyntston or with a scharp bon, whanne men wil go to kutte hem: For who so kutte hem with iren, it wolde destroye his vertue and his nature.”

The old knight has left a record of his impressions of the country near the shores of the Dead Sea, and has given a sketch of those Apple-trees of which Byron wrote—

These trees producing Dead Sea fruit he tells us bore “fulle faire Apples, and faire of colour to behold; but whoso brekethe hem or cuttethe hem in two, he schalle fynd with in hem Coles and Cyndres, in tokene that, be wratthe of God, the cytees and the lond weren brente and sonken in to Helle.”

Dead Sea Fruit. From Maundevile’s Travels.

In Zahn’s Speculæ Physico-Mathematico-Historicæ we read of a peculiar Mexican tree, called Tetlatia or Gao, which causes both men and animals to lose their hair if they rub themselves against its trunk or sleep beneath its branches. Then we are told of a tree growing in Sofala, Africa, which yields no leaf during the whole year, but if a branch be cut off and placed in water, it grows green in ten hours, and produces abundance of leaves. Again, we read of the Zeibas, immense trees “in the new Kingdom of Granada,” which fifteen men could scarcely encompass with their arms; and which, wonderful to relate, cast all their leaves every twelve hours, and soon afterwards acquire other leaves in their place.

A certain tree is described as growing in America, which bears flowers like a heart, consisting of many white leaves, which are red within, and give forth a wonderfully sweet fragrance: these flowers are said to comfort and refresh the heart in a remarkable manner. A curious account is given of a plant, which Nierenbergius states grows in Bengal, which attracts wood so forcibly, that it apparently seizes it from the hands of men. A similar plant is said to exist in the island of Zeilan, which, if placed between two pieces of wood, each distant twenty paces from it, will draw them together and unite them.

Respecting the Boriza, a plant also known as the Lunaria or Lunar Herb, Zahn states that it is so called because it increases and decreases according to the changes of the moon: for when the moon is one day old, this plant has one leaf, and increases the number of leaves in proportion to the moon’s age until it is fifteen days old; then, as the moon decreases, its leaves one by one fall off. In the no-moon period, being deprived of all its leaves, it hides itself. Just as the Boriza is influenced by the moon, so are certain shrubs under the sway of the sun. These shrubs are described as growing up daily from the sand until noon, when they gradually diminish, and finally return to the earth at sunset.

Gerarde tells us that among the wonders of England, worthy of great admiration, is a kind of wood, called Stony Wood, alterable into the hardness of a stone by the action of water. This strange alteration of Nature, he adds, is to be seen in sundry parts of England and Wales; and then he relates how he himself “being at Rougby (about such time as our fantasticke people did with great concourse and multitudes repaire and run headlong unto the sacred wells of Newnam Regis, in the edge of Warwickshire, as unto the water of life, which could cure all diseases),” went from thence unto these wells, “where I found growing ouer the same a faire Ashe-tree, whose boughs did hang ouer the spring of water, whereof some that were seare and rotten, and some that of purpose were broken off, fell into the water and were all turned into stones. Of these boughes or parts of the tree I brought into London, which when I had broken in pieces, therein might be seene that the pith and all the rest was turned into stones, still remaining the same shape and fashion that they were of before they were in the water.”

The Stone Tree. From Gerarde’s Herbal.

In Hainam, a Chinese island, grows a certain tree known as the Fig of Paradise. Its growth is peculiar: from the centre of a cluster of six or seven leaves springs a branch with no leaves, but a profusion of fruit resembling Figs. The leaves of this tree are so large and so far apart, that a man could easily wrap himself up in them; hence it is supposed that our first parents, after losing their innocence, clothed themselves with the leaves of a tree of this species.

The island of Ferro, one of the Canaries, is said to be without rivers, fountains, and wells. However, it has a peculiar tree, as Metellus mentions, surrounded by walls like a fountain. It resembles the Nut-tree; and from its leaves there drops water which is drinkable by cattle and men. A certain courtesan of the island, when it was first subdued, made it known to the Spaniards. Her perfidy, however, is said to have been discovered and punished with death by her own people.

Bishop Fleetwood gives the following description, by Hermannus Nicolaus, of what he calls the Distillatory Plant:—“Great are the works of the Lord, says the wise man; we cannot consider them without ravishment. The Distillatory Plant is one of these prodigies of nature, which we cannot behold without being struck with admiration. And what most surprises me is the delicious nectar, with which it has often supplied me in so great abundance to refresh me when I was thirsty to death and unsufferably weary…. But the greatest wonder of it is the little purse, or if you will, a small vessel, as long and as big as the little finger, that is at the end of each leaf. It opens and shuts with a little lid that is fastened to the top of it. These little purses are full of a cool, sweet, clear cordial and very agreeable water. The kindness this liquor has done me when I have been parched up with thirst, makes me always think of it with pleasure. One plant yields enough to refresh and quench the thirst of a man who is very dry. The plant attracts by its roots the moisture of the earth, which the sun by his heat rarifies and raises up through the stem and the branches into the leaves, where it filtrates itself to drop into the little recipients that are at the end of them. This delicious sap remains in these little vessels till it be drawn out; and it must be observed that they continue close shut till the liquor be well concocted and digested, and open of themselves when the juice is good to drink. ’Tis of wonderful virtue to extinguish speedily the heats of burning fevers. Outwardly applied, it heals ring-worms, St. Anthony’s Fire, and inflammations.”

Plants Bearing Inscriptions and Figures.

Gerarde has told us that in the root of the Brake Fern, the figure of a spread-eagle may be traced; and Maundevile has asserted that the fruit of the Banana, cut it how you will, exhibits a representation of the Holy Cross. L. Sarius, in his Chronicles to the year 1559, records that, in Wales, an Ash was uprooted during a tempest, and in its massive trunk, rent asunder by the violence of the storm, a cross was plainly depicted, about a foot long. This cross remained for many years visible in the shattered trunk of the Ash, and was regarded with superstitious awe by the Catholics as having been Divinely sent to reprove the officious zeal of Queen Elizabeth in banishing sacred images from the Churches.

In Zahn’s work is an account—“resting on the sworn testimony of the worthiest men,” and on the authority of an archbishop—of the holy name Jesu found in a Beech that had been felled near Treves. The youth, who was engaged in chopping up this tree, observed while doing so, a cloud or film surrounding the pith of the wood. Astonished at the sight, he called his uncle Hermann, who noticed at once the sacred name in a yellow colour, changing to black. Hermann carried the wood home to his wife, who had long been an invalid, and she, regarding it as a precious relic, received much comfort, and finally, in answer to daily prayer, her strength was restored. After this, the wood was presented to the Elector Maximilian Henry, who was so struck with the phenomenon, that he had it placed in a rich silver covering, and publicly exposed as a sacred relic in a church; and on the spot where the tree was cut, he caused a chapel to be erected, to preserve the name of Jesu in everlasting remembrance.

In the same work, we are told that in a certain root, called Ophoides, a serpent is clearly represented; that the root of Astragalus depicts the stars; that in the trunk of the Quiacus, a dog’s head was found delineated, together with the perfect figure of a bird; that the trunk of a tree, when cut, displayed on its inner surface eight Danish words; that in a Beech cut down by a joiner, was found the marvellous representation of a thief hanging on a gibbet; and that in another piece of wood adhering to the former was depicted a ladder such as was used in those days by public executioners: these figures were distinctly delineated in a black tint. In 1628, in the wood of a fruit-tree that had been cut down near Haarlem, in Holland, the images of bishops, tortoises, and many other things were seen; and one Schefferus, a physician, has recorded that near the same place, a piece of wood was found in which there was given “a wonderful representation by Nature of a most orderly star with six rays.” Evelyn, in his ‘Sylva,’ speaks of a tree found in Holland, which, being cleft, exhibited the figures of a chalice, a priest’s alb, his stole, and several other pontifical vestments. Of this sort, he adds, was an Oxfordshire Elm, “a block of which wood being cleft, there came out a piece so exactly resembling a shoulder of veal, that it was worthy to be reckoned among the curiosities of this nature.” Evelyn also notices a certain dining-table made of an old Ash, whereon was figured in the wood fish, men, and beasts. In the root of a white Briony was discovered the perfect image of a human being: this curious root was preserved in the Museum at Bologna. Many examples of human figures in the roots of Mandrakes have been known, and Aldrovandus tell us that he was presented with a Mandrake-root, in which the image was perfect.

Vegetable Monstrosities.

It is related that, in the year 1670, there was exposed for sale, in the public market of Vratislavia, an extraordinary wild Bugloss, which, on account of the curiosity of the spectators and the different superstitious speculations of the crowd, was regarded not only as something monstrous but also as marvellous. This Bugloss was a little tortuous and 25 inches in length. Its breadth was 4 inches. It possessed a huge and very broad stem, the fibres of which ran parallel to each other in a direct line. It bore flowers in the greatest abundance, and had at least one root.

Aldrovandus, in his Liber de Monstris, describes Grapes with beards, which were seen in the year 1541 in Germany, in the province of Albersweiler. They were sent as a present, first to Louis, Duke of Bavaria, and then to King Ferdinand and other princes.

Zahn figures, in his work, a Pear of unusual size which was gathered from a tree growing in the Royal Garden at Stuttgart, towards the close of June, 1644. This Pear strongly resembled a human face, with the features distinctly delineated, and at the end, forming a sort of crown, were eight small leaves and two young shoots with a blossom at the apex of each. This curious and unique vegetable monstrosity was presented to his Serene Highness the Prince of Wurtemburg.

In the same book is given a description of a monstrous Rape—bearing a striking resemblance to the figure of a man seated, and exhibiting perfectly body, arms, and head, on which the sprouting foliage took the place of hair. This Rape grew in the garden of a nobleman in the province of Weiden, in the year 1628.

Mention is made of a Daucus which was planted and became unusually large in size. Some pronounced it to be a Parsnip, having a yellow root, and thin leaves. This Parsnip had an immense root, like a human hand, which, from its peculiar growth, had the appearance of grasping the Daucus itself.

In Zahn’s book are recorded many other vegetable marvels: amongst them is the case of a Reed growing in the belly of an elephant; a ear of Wheat in the nose of an Italian woman; Oats in the stomach of a soldier; and various grains found in wounds and ulcers, in different parts of the human body.

Miraculous Trees and Plants.

There are some few plants which have at different times been prominently brought into notice by their intimate association with miracles. Such a one was the branch of the Almond-tree forming the rod of Aaron, which, when placed by Moses in the Tabernacle, miraculously budded and blossomed in the night, as a sign that its owner should be chosen for High Priest. Such, again, was the staff of Joseph of Arimathea, which, when driven, one Christmas-day, into the ground at Glastonbury, took root and produced a Thorn-tree, which always blossomed on that day. Such, again, was the staff of St. Martin, from which sprang up a goodly Yew, in the cloister of Vreton, in Brittany; and such was the staff of St. Serf, which, thrown by him across the sea from Inchkeith to Culross, straightway took root and became an Apple-tree.

In the same category must be included the tree miraculously secured by St. Thomas, the apostle of the Indians, and from which he was enabled to construct a church, inasmuch as when the sawdust emitted by the tree when being sawn was sown, trees sprang up therefrom. The tree (represented as being a species of Kalpadruma) was hewn on the Peak of Adam, in Ceylon, by two servants of St. Thomas, and dragged by him into the sea, where he appears to have left it with the command, “Vade, expecta nos in portu civitatis Mirapolis.” … When it reached its destination, this tree had grown to such an enormous bulk, that although the king and his army of ten thousand troops, with many elephants, did their utmost to secure it and drag it on shore, they were unable to move it. Mortified at his failure, the king descried the holy Apostle Thomas approaching, riding upon an ass. The holy Apostle was accompanied by his two servants, and by two great lions. “Forbear,” said he, addressing the king: “Touch not the wood, for it is mine.” “How can you prove it is yours?” enquired the king. Then Thomas, loosing his girdle, threw it to the two servants, and bade them tie it around the tree; this they speedily did, and, with the assistance of the lions, dragged the huge trunk ashore. The king was astonished and convinced by the miracle, and at once offered to Thomas as much land whereon to erect a church to his God as he cared to ride round on his ass. So with the aid of the miraculous tree the Apostle Thomas set to work to build his church. When his workmen were hungry he took some of the sawdust of the tree, and converted it into Rice; when they demanded payment, he broke off a small piece of the wood, which instantly became changed into money.

Popular tradition has everywhere preserved the remembrance of a certain Arbor secco, which, according to Marco Polo, Frate Odorico, and the Book of Sidrach, existed in the East. This Arbor secco of the Christians is the veritable Tree of the Sun of the ancient pagans. Marco Polo calls the tree the Withered Tree of the Sun, and places it in the confines of Persia; Odorico, near Sauris. According to Maundevile, the tree had existed at Mamre from the beginning of the world. It was an Oak, and had been held in special veneration since the time of Abraham. The Saracens called it Dirpe, and the people of the country, the Withered Tree, because from the date of the Passion of Our Lord, it has been withered, and will remain so until a Prince of the West shall come with the Christians to conquer the Holy Land: then “he shalle do synge a masse undir that dry tree, and than the tree shalle waxen grene and bere bothe fruyt and leves.” Fra Mauro, in his map of the world, represents the Withered Tree in the middle of Central Asia. It has been surmised that this Withered Tree is no other than that alluded to by the Prophet Ezekiel (xvii., 24): “And all the trees of the field shall know that I the Lord have brought down the high tree, have exalted the low tree, have dried up the green tree.”

Arbor Secco, or The Withered Tree. From Maundevile’s Travels.

Sulpicius Severus relates that an abbot, in order to test the patience of a novice, planted in the ground a branch of Styrax that he chanced to have in his hand, and commanded the Novice to water it every day with water to be obtained from the Nile, which was two miles from the monastery. For two years the novice obeyed his superior’s injunction faithfully, going every day to the banks of the river, and carrying back on his shoulder a supply of Nile water wherewith to water the apparently lifeless branch. At length, however, his steadfastness was rewarded, for in the third year the branch miraculously shot out very fine leaves, and afterwards produced flowers. The historian adds that he saw in the monastery some slips of the same tree, which they took delight to cultivate as a memento of what the Almighty had been pleased to do to reward the obedience of his servant.

Another miraculous tree is alluded to in Fleetwood’s ‘Curiosities,’ where, on the authority of Philostratus, the author describes a certain talking Elm of Ethiopia, which, during a discussion held under its branches between Apollonius and Thespesio, chief of the Gymnosophists, reverently “bowed itself down and saluted Apollonius, giving him the title of Wise, with a distinct but weak and shrill voice, like a woman.”

The blind man to whom our Saviour restored his sight said, at first, “I see men walking as if they were trees!” one Anastasius of Nice, however, has recorded that, oppositely, he had seen trees walk as if they were men. Bishop Fleetwood remarks that this Anastasius, being persuaded that by miraculous means our neighbours’ trees may be brought into our own field, relates that a heretic of Zizicum, of the sect of the Pneumatomachians, had, by the virtue of his art, brought near to his own house a great Olive-tree belonging to one of his neighbours, that he and his disciples might have the benefit of the freshness of the shade to protect them from the heat of the sun. By this art, also, it was that the plantation of Olives, belonging to Vectidius, changed its place.

Maundevile has preserved a record of a tree of miraculous origin, that in his time grew in the city of Tiberias. The old knight writes:—“In that cytee a man cast an brennynge [a burning] dart in wratthe after oure Lord, and the hed smote in to the eerthe, and wex grene, and it growed to a gret tree; and yit it growethe, and the bark there of is alle lyke coles.”

Miraculous Tree of Tiberias. From Maundevile’s Travels.

Among flowers, the Rose—the especial flower of martyrdom—has been the most connected with miracles. Maundevile gives it a miraculous origin, alleging that at Bethlehem the faggots lighted to burn an innocent maiden were, owing to her earnest prayers, extinguished and miraculously changed into bushes which bore the first Roses, both white and red. According to monastic tradition, the martyr-saint Dorothea sent a basket of Roses miraculously to the notary Theophilus, from the garden of Paradise. The Romish legend of St. Cecilia relates that after Valerian, her husband, had been converted and baptised by St. Urban, he returned to his home, and heard, as he entered it, the most enchanting music. On reaching his wife’s apartment, he beheld an angel standing near her, who held in his hand two crowns of Roses gathered in Paradise, immortal in their freshness and perfume, but invisible to the eyes of unbelievers. With these the angel encircled the brows of Cecilia and Valerian, and promised that the eyes of Tiburtius, Valerian’s brother, should be opened to the truth. Then he vanished. Soon afterwards Tiburtius entered the chamber, and perceiving the fragrance of the celestial Roses, but not seeing them, and knowing that it was not the season for flowers, he was astonished, yielded to the fervid appeal of St. Cecilia, and became a Christian.

St. Elizabeth, of Hungary, is always represented with Roses in her lap or hand, in allusion to a legend which relates that this saint, the type of female charity, one day, in the depth of winter, left her husband’s castle, carrying in the skirts of her robe a supply of provisions for a certain poor family; and as she was descending the frozen and slippery path, her husband, returning from the chase, met her bending under the weight of her charitable burden. “What dost thou here, my Elizabeth?” he asked: “let us see what thou art carrying away.” Then she, confused and blushing to be so discovered, pressed her mantle to her bosom; but he insisted, and opening her robe, he beheld only red and white Roses, more beautiful and fragrant than any that grow on this earth, even at summer-tide, and it was now the depth of winter! Turning to embrace his wife, he was so overawed by the supernatural glory exhibited on her face, that he dared not touch her; but, bidding her proceed on her mission, he took one of the Roses of Paradise from her lap, and placed it reverently in his breast.

Trithemius narrates that Albertus Magnus, in the depths of winter, gave to King William on the festival of Epiphany a most elegant banquet in the little garden of his Monastery. Suddenly, although the monastery itself was covered with snow, the atmosphere in the garden became balmy, the trees became covered with leaves, and even produced ripe fruit—each tree after its kind. A Vine sent forth a sweet odour and produced fresh grapes in abundance, to the amazement of everyone. Flocks of birds of all kinds were attracted to the spot, and, rejoicing at the summer-like temperature, burst into song. At length, the wonderful entertainment came to an end, the tables were removed, and the servants all retired from the grounds. Then the singing of the birds ceased, the green of the trees, shrubs, and grasses speedily faded and withered, the flowers drooped and perished, the masses of snow which had so strangely disappeared now covered everything, and a piercing cold of great intensity obliged the king and his fellow-guests to seek shelter and warmth within the Monastery walls. Greatly astonished and moved at what he had seen, King William called Albertus to him, and promised to grant him whatever he might request. Albertus asked for land in the State of Utrecht, whereon to erect a Monastery of his own order. His request was granted, and he also obtained from the King many other favours.

It is recorded that on the same day that Alexander de’ Medici, the Duke of Florence, was treacherously killed, in the Villa of Cosmo de’ Medici, an abundance of all kinds of flowers burst into bloom, although quite out of the flowering season; and on that day the Cosmian gardens alone appeared gay with flowers, as though Spring had come.

Father Garnet’s Straw.

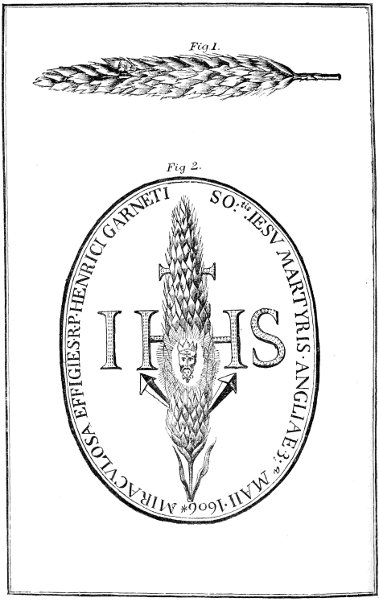

At the commencement of the present chapter on extraordinary and miraculous plants, allusion was made to certain trees which were reputed to have borne as fruit human heads. A fitting conclusion to this list of wonders would appear to be an account of a wondrous ear of Straw, which, in the year 1606, was stated miraculously to have borne in effigy the head of Father Garnet, who was executed for complicity in the Gunpowder Plot. It would seem that, after the execution of Garnet and his companion Oldcorne, tales of miracles performed in vindication of their innocence, and in honour of their martyrdom, were circulated by the Jesuits. But the miracle most insisted upon as a supernatural confirmation of the Jesuit’s innocence and martyrdom, was the story of Father Garnet’s Straw. The originator of this miracle was supposed to be one John Wilkinson, a young Catholic, who, at the time of Garnet’s trial and execution, was about to pass over into France, to commence his studies at the Jesuits’ college at St. Omers. Some time after his arrival there, Wilkinson was attacked by a dangerous disease, from which there was no hope of recovery; and while in this state he gave utterance to the story, which Eudæmon-Joannes relates in his own words. Having described his strong impression that he should “witness some immediate testimony from God in favour of the innocence of His saint,” his attendance at the execution, and its details, he proceeds thus:—“Garnet’s limbs having been divided into four parts, and placed together with the head in a basket, in order that they might be exhibited according to law in some conspicuous place, the crowd began to disperse. I then again approached close to the scaffold, and stood between the cart and the place of execution; and as I lingered in that situation, still burning with the desire of bearing away some relique, that miraculous ear of Straw, since so highly celebrated, came, I know not how, into my hand. A considerable quantity of dry Straw had been thrown with Garnet’s head and quarters from the scaffold into the basket; but whether this ear came into my hand from the scaffold or from the basket, I cannot venture to affirm: this only I can truly say, that a Straw of this kind was thrown towards me before it had touched the ground. This Straw I afterwards delivered to Mrs. N., a matron of singular Catholic piety, who inclosed it in a bottle, which being rather shorter than the Straw, it became slightly bent. A few days afterwards, Mrs. N. showed the Straw in the bottle to a certain noble person, her intimate acquaintance, who, looking at it attentively, at length said, ‘I can see nothing in it but a man’s face.’ At this, Mrs. N. and I, being astonished at the unexpected exclamation, again and again examined the ear of Straw, and distinctly perceived in it a human countenance, which others, also coming in as casual spectators, or expressly called by us as witnesses, also beheld at that time. This is, as God knoweth, the true history of Father Garnet’s Straw.”

In process of time, the fame of the prodigy encouraged those who had an interest in upholding it to add considerably to the miracle as it was at first promulgated. Wilkinson and the first observers of the marvel merely represented that the appearance of a face was shown on so diminutive a scale, upon the husk or sheath of a single grain, as scarcely to be visible unless specifically pointed out. Fig. 1 in the accompanying plate accurately depicts the miracle as it was at first displayed.

But a much more imposing image was afterwards discovered. Two faces appeared upon the middle part of the Straw, both surrounded with rays of glory; the head of the principal figure, which represented Garnet, was encircled with a martyr’s crown, and the face of a cherub appeared in the midst of his beard. In this improved state of the miracle, the story was circulated in England, and excited the most profound and universal attention; and thus depicted, the miraculous Straw became generally known throughout the Christian world. Fig. 2 in the sketch exactly represents the prodigy in its improved state: it is taken from the frontispiece to the ‘Apology of Eudæmon-Joannes.’

So great was the scandal occasioned by this story of Father Garnet’s miraculous Straw, that Archbishop Bancroft was commissioned by the Privy Council to institute an inquiry, and, if possible, to detect and punish the perpetration of what he considered a gross imposture; but although a great many persons were examined, no distinct evidence of imposition could be obtained. It was proved, however, that the face might have been limned on the Straw by Wilkinson, or under his direction, during the interval which occurred between the time of Garnet’s death and the discovery of the miraculous head. At all events, the inquiry had the desired effect of staying public curiosity in England; and upon this the Privy Council took no further proceedings against any of the parties. Folkard, Plant Lore

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.