https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/public/gdcmassbookdig/williamclaiborne00clai/williamclaiborne00clai.pdf

INTRODUCTION

UNTIL now the biography of William Claiborne, the foremost genius of early Virginia, has never been fully written. Religious, political, and even family prejudices have tended hitherto to give us distorted pictures of his life and public services. Dr. Claiborne’s account of his distinguished ancestor’s career shuns fable and corrects tradition. It is much more than a well-told story. It is a loyal acknowledgment of the qualities of a man who figured in many strong and pathetic episodes during a period of dramatic unrest.

If not the most conspicuous, Claiborne was beyond question the most powerful and influential, character in the days when the Old Dominion began its development, and throughout the stormy times which followed. His biographer makes his presentation with fidelity to a high ideal—the desire to offer no homage less pure or noble than the truth. [vii]

Mr. Claiborne, Captain, Colonel, Secretary, and eventually Parliamentary Commissioner, was a typical man of an age of universal curiosity and romantic aspiration. It may be that his appointment as Royal Surveyor was due to the intercession of his titled kinswoman, but he was already a man of proven talents when, at the age of thirty-four, he was selected to accompany Sir Francis Wyatt to Virginia in that capacity.

George Calvert, who had been one of the original associates of the London Company, and later of the governing council, and who four years subsequently was elevated to the Irish peerage with the title of Baron Baltimore, was then Secretary of State and one of James’s most intimate favourites, owing doubtless to his Spanish leanings. While Claiborne was Protestant, Calvert was Catholic a Catholic convert. Calvert well reflects the attitude of his period. It was a ruder and rougher age than our own, with hardly any perceptible advantages and much that gave life a gloomier tinge.

It is not imaginable to those who have not tried, to what labours an historian who would be exact is condemned. He must read all, good and bad, and remove a pile of rubbish before he can lay the foundation. Dr. Claiborne can never be [viii] accused of failure to perform this duty, nor of undue dependence upon others, nor of writing up to a purpose. His object is to exhibit as faithfully as words can portray, the exact character of his ancestor, the circumstances which surrounded him, and the motives external and internal by which he was impelled in the drama in which he played so conspicuous a part.

The affections of a people for a locality depend upon the sense in which it is really and truly their home. Men will fight for their homes because without a home they and their families are turned shelterless adrift. But the idea of home is inseparably connected with the possession or permanent occupation of land. The fortunes of the owners of the soil of any country are bound up in the fortunes of the country to which they belong, and thus those nations have always been the most stable in which the land is most widely divided or where the largest number of people have a personal concern in it. Interest and natural feeling alike coincide to produce this effect.

The sovereigns of England are the head of the kingdom, and so by ancient prescription were the head and root from which all land tenures sprang. All undistributed land within the realm including confiscated and forfeited estates, as well as all [ix] territory abroad acquired by conquest or discovery, were held of the Crown, by which is meant the sovereign in his political capacity.

The first English colonial charter was that granted in 1578 by Elizabeth to Sir Walter Raleigh’s half- brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert. Many of the articles of this remarkable instrument merit attention, unfolding as they do the ideas of that age with respect to the nature of such enterprises, but those only which deal with the property and political rights which were promised to the colonists are of present importance. After authorizing Gilbert to discover and take possession of all remote and barbarous lands, unoccupied by any Christian prince or people, Elizabeth vested in Gilbert, his heirs and assigns forever, the full rights of property in the soil of those countries of which he might take possession, to be held of the Crown of England “by homage,” on the payment of the fifth part of the gold or silver ore found there, with power to convey to settlers such portions of the lands as Gilbert might judge meet, according to the laws of England. She declared further that the settlers should have and enjoy all the privileges of free denizens and ^ In feudal law an admission or acknowledgment to the lord of tenure under him. [x] natives of England. It will be noted that while Gilbert’s patent was limitless as to the range of his explorations, provided he did not invade places already occupied by Christian nations, he acquired the ownership only of the places of which he actually took possession. The charter granted to Raleigh in 1584 still more distinctly specified lands “not actually possessed of any Christian prince, nor inhabited by Christian people.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth, formally protesting against the all-embracing claims asserted by Spain when that nation demanded the return of the treasures captured by Drake, held it to be a doctrine of public law that neither first discovery nor a mere assertion of right could prevail against occupation in fact. The Spaniards, she declared, had no right to regions which they had merely discovered or touched upon; the naming of rivers and capes or the building of huts was not enough. The same principle was recognized by James in the instructions given to the Virginia patentees in 1606, and fifteen years later Parliament, in denying the rights of Spain in America based on the gift of Pope Alexander VI., declared that possession and occupancy only, and not the mere fact of discovery, confer a good title. In 1604 James concluded a treaty with Spain which,[ xi] excluding English subjects from the Spanish West Indies and thus putting a damper on their buccaneering ardour, helped to spread the growing interest in American colonization. The original charter by which James conveyed to the London Company the vast territory then known as South Virginia provided for the conveyance of lands to the settlers by tenures as liberal as those prescribed in the Gilbert and Raleigh patents; and the later charters were equally explicit as well in this regard as in confirming the political rights and liberties of the settlers. But these were paper guarantees. No right of private property in land was in fact established in the colony until 1616. Up to that time the settlers were treated as vassals of the Company. The fields that were cleared were cultivated by their joint labour, the product being carried to common storehouses, whence it was distributed at appointed times. The houses in which they lived belonged to the Company. A community conducted on such a plan was not destined to prosper. There was no inducement to labour when there was no prospect of securing a permanent habitation and nothing to acquire except what was bestowed on all alike. The idle and incompetent shared equally with the prudent and attentive. The Company receiving the sole [xii] benefit of labour, the exertions of even the most industrious settlers relaxed, and eventually matters came to such a pitch that the united industry of the colony did not accomplish in a week as much as might have been performed in a single day if each individual had laboured on his own account. At last Governor Dale, realizing the folly and stupidity of such a policy, divided a considerable portion of the land into parcels, one of which was given to each individual in full property. From that moment the colony began to advance. A different and better class of immigrants was attracted and a new spirit was at work in the Company. In 1 619 the control of its affairs passed into the hands of men of wide social and political interest such as the Earl of Southampton, Nicholas Ferrar, and the unfortunate Sandys who was later committed to the Tower for no other reason than that his behaviour in Parliament was displeasing to the King, notwithstanding which Calvert brazenly declared that he had not been committed “for any parliamentary matter. ” Under them a constitution was granted in 1621 which became the model of all subsequent governments in the American colonies. Through their influence Sir Francis Wyatt was appointed Governor. Claiborne, bearing his commission as Royal Surveyor, was a [xiii] member of Wyatt’s expedition which brought the constitution to Virginia, The same year Calvert established his settlement of Avalon in Newfoundland for which two years later James gave him a proprietary charter.

Under the new control the affairs of the colony were administered with great energy with a view to its ultimate prosperity, rather than an immediate profit, but just when the prospects seemed brightest the Spanish party, of which Calvert was always the ready instrument, prevailed. The government of Spain had watched the progress of the colony with jealous vigilance and determined to destroy it. A clique was formed against Southampton and Sandys. The former was in disgrace and Sandys had never been in favour. But unpopular as they were at court, they had friends in Parliament, so that on James’s demand for the surrender of the Company’s charter the Commons decided to inquire into the merits of the controversy, and the projected investigation was only abandoned when Calvert communicated to the House the King’s pronouncement that the matter was one with which only his council was concerned. Although the Company was torn asunder by internal dissensions, Southampton and his supporters were still in control, so that James’s [xiv] demand for the surrender of the charter was met by a refusal. Then followed the quo warranto proceedings and the extinction of the Company’s political rights.

Broad-minded and public-spirited though the policy of the Company had been in its later days and little justice as there was in the judgment of the King’s Bench, yet in all likelihood the colony was the gainer by its overthrow. The proclamation suspending the powers of the Company was dated July 15, 1624. Virginia thereupon became a royal province and Wyatt was continued as Governor under the King’s commission instead of under that of the Company. On March 27th of the following year James closed by death his inglorious and oppressive reign. Calvert remained in office less than a year after Charles’s accession. In 1627, finding his Newfoundland settlement not to his taste or expectations, he petitioned the King for a grant of land in Virginia. Despite Charles’s admonition to give up his venture and return to England, he emigrated to that colony with his family. There the colonial government demanded that he take the oaths of supremacy and allegiance whereby he would have had to renounce the spiritual and ecclesiastical authority of the Pope. Calvert, now Lord Baltimore, as a peer was exempt [xv] Introduction from the second of these oaths, and it is doubtful whether any authority resident in Virginia had a right to administer either. Baltimore, instead of putting the question to a test, retired to England.

In 1 63 1 Claiborne, having enlisted the requisite financial backing and doubtless suspecting Baltimore’s intentions, obtained from Charles a license under the privy seal of Scotland empowering him and his associates “freely and without interruption to trade and traffic in or near those parts of America for which there is not already a patent granted to others for trade.” By this time the trading post on Kent Island had become the nucleus of a flourishing settlement which in 1632 sent a Burgess to the General Assembly of Virginia. Claiborne had purchased it from the Indians and it had been highly cultivated. That these facts were fully known to Charles is made clear by the language of the Maryland charter which conveyed to Baltimore “a certain region in parts of America not yet cultivated and in possession of savages or barbarians having no knowledge of the Divine Being.” Moreover, while Baltimore was authorized as Lord Proprietor to make ordinances agreeable to reason and the laws of England, he was forbidden to extend them to the life or estate of [xvi] any emigrant. The Calverts, despite their intimacy with Sir Francis Windebank the new Secretary of State and with the Earl of Portland and Lord Cottington, were not to be permitted to despoil the Virginians of any of the territory they had settled. Kent Island seemed safe until the Virginians were undeceived by Calvert’s open avowal of his claim to it. Claiborne and the whole colony were naturally incensed at this, and their rage was increased when Claiborne’s second protest and that of the London Company were referred to the Star Chamber of which Windebank and his friends in the Council were members. The decision of that ever-to-be-abhorred tribunal was that Baltimore should be left to his charter and the Virginians to the course of the law. Thus matters rested until Calvert arrived at Point Comfort in 1634. From this point on Dr. Claiborne takes the narrative in hand still more vigorously and presents the facts in quick and dramatic succession. He refers in just and condemnatory terms to the treachery of George Evelin through which Kent Island was surrendered to Baltimore’s ruffians, and his treatment of the void Bill of Attainder shows it to have been a piece of contemptible revenge. Within two weeks after the passage of [xvii] the bill the Lords Commissioners rendered their decision in favour of Baltimore. Charles, whose every act had so far indicated his sympathy with Claiborne and who showed his displeasure at the unjust decision of the Commissioners, abandoned Claiborne to his enemies after Baltimore had waited on him and had given him, as Baltimore said he would, “perfect satisfaction.” It would be interesting to know what the nature of this “perfect satisfaction” was.

Virginia has been described as a cavalier colony connected by origin with the class of great land owners. As a matter of fact the settlers mostly came from the upper middle class and the smaller landed gentry, with a mixture of well-to-do tradesmen. This being so, it was fairly certain that in the Civil War there would be nothing like unanimity of sympathy amongst the inhabitants; and so it proved. But though men differed, few held their opinions with tenacity; Claiborne and a few others were the exceptions.

The action of Virginia at the outset of the war was determined by Governor Berkeley, a frank, strenuous, blustering Cavalier. An act was passed declaring that all commissions given by Charles were valid and making it penal to express sympathy with the Parliament or disapproval of Introduction [xviii] the crown; but the Royalist party collapsed at the first show of force and Claiborne and his followers who were vastly in the majority took matters in hand.

Dr. Claiborne gives the just value to the Ingle-Claiborne invasion of Maryland. He points out that authorities agree that Claiborne simply made use of Ingle to further his ends, that the association was incidental, and that there was no collusion between the two men. Many have described Claiborne’s part in this affair as that of a beaten man seeking revenge. There is no support for any such theory. Claiborne was a Parliament man and had he done less he would have failed to perform his full duty to his government. Dr. Claiborne points out also that the easy terms given to the Virginia Colony on its surrender to the parliamentary commissioners were largely the result, probably, of Claiborne’s influence, and he demonstrates with clearness that Claiborne’s part in the reduction of Maryland was not inspired by personal revenge or malice. In support of his convictions, it is worthy of note that all the acts of the commissioners in the reduction of that province were approved by the Commonwealth. He cites Latane and Fiske to support his views.

In conclusion it is well to refer at some length to Claiborne’s petition to Charles 11. for the restoration of Kent Island, inasmuch as that final petition, particularly the wording of it, has been used by a recent writer as the text for much animadversion and unintelligent criticism.

Claiborne’s petition to Charles II. for the res- oration of Kent Island has been called a servile paper by those ignorant of the forms and ceremonies then prevalent. It was in truth a pathetic document. But let us remember that Claiborne was at the time a very old man and that the spoliation of the property he cherished more highly than anything he had ever possessed had been rankling in his bosom for many years. Small wonder he worded his petition in plaintive language. But that was merely the custom of the age. Let us compare it with the remonstrance of the City of London against Charles’s levy of ship-money. Your petitioners [said the infuriated corporation] do in all submissive humbleness and with acknowledgement of your sacred Majesty’s many favours unto your said city inform your Majesty that they conceive that by ancient privileges, grants, and acts of parliament (which they are ready humbly to showforth) they are exempt and are to be freed from that charge, and do most humbly pray that your Majesty will be graciously pleased, that the petitioners, with [xx] your princely grace and favour, may enjoy the said privileges and exemptions, and be freed from providing the said ships and provisions. And they shall pray, etc. Was there more spirit in this document than in Claiborne’s bold assertion that Charles’s father had deliberately condoned, if indeed he had not in the end connived at it, the illegal expulsion of Claiborne from his estate? Though the faithless monarch turned a deaf ear to his appeal, Claiborne’s countrymen were not remiss in making substantial acknowledgment of his long and faithful services in their interest, and in undoing, so far as they could, the great wrong that had been done him. The grants by which he was compensated by Virginia comprised over twenty thousand acres of the richest lands in the province. In view of the facts as set forth by the author of this narrative, it is difficult to understand the abuse and condemnation which have been visited upon Claiborne by historians. A man who was honoured by all the sovereigns under whom he lived, by the Commonwealth, even by his ancient enemy Berkeley himself and by his fellow Virginians, who received the highest gift of state except that of the governorship and held it for xxii Introduction years, who waged the first successful war against the Indians in the early days of the colony, and who was later appointed General-in-Chief of all the colonial forces, cannot have merited such obloquy. The narrative should conclusively settle the opinion of posterity concerning the character, deeds, and achievements of William Claiborne. – John D. Lindsay. New York, October, 191 7. [xxi]

PREFACE

THE incidents with which this book deals are well known in the history of the early relations between Virginia and Maryland. The literature touching on the subject is voluminous. The two main actors in the drama are Lord Balti- more and William Claiborne of Virginia. Until i860, practically one opinion was held concerning William Claiborne and the contention between him and Lord Baltimore for the possession of Kent Island, and the sweeping condemnation which was heaped upon Claiborne by reason of his acts and attitude toward Baltimore and the Maryland Government remained unchallenged until about that date. Since then and more recently, several writers have laid aside prejudice and rendered him some measure of justice. It is the author’s purpose to show that Yv^illiam Claiborne’s claim to the possession of Kent Island was just and unequivocal ; that at no time was he subject to Lord Baltimore’s jurisdiction; that Kent Island itself, up to the time of the decision of the XXIV Preface Lords Commissioners in 1638, was an integral part of Virginia under the dominion of the Kingand not under the sovereignty of Baltimore; that the first act of aggression between the two protagonists was committed by the accredited agents of Baltimore in the seizure of Claiborne’s ship The Long Tail in April, 1635; that since Claiborne’s right to trade in those waters (without molestation or stoppage) , in which the seizure occurred, had been given expressly and emphatically by the King in a Royal letter and that since at that time the King’s word was law, the act of seizure of The Long Tail by Baltimore’s agents was unlawful and must be classed as piracy; that the subsequent engagement between Claiborne’s ship and those of Baltimore was an act of reprisal in what may be described as civil war between Maryland and Virginia; that therefore, the onus of this condition of affairs lay upon Baltimore and not upon Claiborne; that the Bill of Attainder passed by the Maryland Assembly in 1637 was iniquitous, illegal, ineffective, and incompetent; that the right to pass a Bill of Attainder was vested in the English Parliament alone and could not under any circumstances be transmitted to or assumed by any colonial legislative body such as the Assembly of Maryland which passed it; that Preface XXV the seizure and confiscation of all of Claiborne’s property by reason of that Act was contrary to law and was a high-handed outrage against English rights; that by reason of this he was denounced as rebel, pirate, and murderer; that William Claiborne was at no time a rebel to Lord Baltimore; that in the Claibome-Ingle invasion of Maryland, he was simply an invading enemy and that in the reduction of Maryland as one of the Parliamentary Commissioners, he was the accredited agent of the de facto Government of England. Considerable space has been given to analysis of Claiborne’s character and acts, and the refutation of the accusations and epithets heaped upon him. The author is indebted to his friend Mr. John D. Lindsay for his masterly definition of the meaning and character of the Act in Parliamentary law known as the Bill of Attainder whereby the total incompetency and ineffectiveness of the one passed by the Maryland Assembly is demonstrated, likewise for the introduction which he has written, and for many other suggestions in the preparation of this work. He feels himself also indebted to Mr. DeCourcy Thom of Maryland, a personal friend of his boyhood, for encouragement, sympathy, and assistance. XXVI Preface A certain philosopher has said “a man is but the sum of his ancestors.” Perhaps it may more properly be said, a man is the sum of his ancestors plus his environment plus his intellectual processes plus his impulses plus his power of inhibition. For this reason in part, this sketch of William Claiborne has been preceded by some account of his pedigree to show what manner of men went before him, while his own acts are set forth in the succeeding pages. Although it is not strictly speaking within the author’s purpose to compare the ultimate personal equations of Baltimore and Claiborne, he feels called upon to point out that a certain amount of historical justice has been rendered by the great leveller—Time ; that whereas, the name of Claiborne has persisted throughout the history of Virginia and has been and is still borne by men of honour and ability who have rendered service in the upbuilding of the republic, Baltimore’s line has passed forever from the earth, unhappily in poverty and shame, and his patronymic from amongst those who are still adorning the fair name of Maryland. The author is not unaware that he is setting forth bold and radical views in contravention of those who have written before him, but he is compelled to do so from a study of the facts, Preface XXVll and he feels that the truth, as he sees it, should be made known to those who bear the name and inherit the blood of William Claiborne. While many authorities have been consulted in the preparation of these pages the author has fol- lowed in the main Latane and also Fiske. He has attempted to arrange the sequence of events with continuity so that the thread of the narrative may be more easily held in the mind. He believes that brevity is an element in clarity. The account of the pedigree of William Claiborne is taken almost bodily from Irish Pedigrees by John O’Hart, fourth edition, volume ii., Benziger Bros., New York, 1888, likewise to a large extent, the description of Cliburn Hall and the Manor. The descent of William Claiborne from Duncan and Ethelred is taken from Americans of Royal Descent by Charles H. Browning; his descent, from Bardolph, from Fitz Randolph Traditions—A Story of a Thousand Years by L. V. F. Randolph, life member of the New Jersey Historical Society, 1907, under the auspices of which the book was published. J. H. C. New York, August, 1917.

William Claiborne of Virginia CHAPTER I

THE DESCENT OF WILLIAM CLAIBORNE FROM BARDOLPH^

COMMENCING with Bardolph, the common progenitor of several noble families of the north, the descent is as follows:

I. Bardolph,^ Lord of Ravenswath and other manors in Richmondshire, was a great landowner in Yorkshire, who gave a carucate of land and the churches of Patrick Brampton and Ravenswath in pure alms to the Abbey of St. Mary’s at York. » Quoted from O’Hart’s Irish Pedigrees. ^ Bardolph: Harrison (see the History of Yorkshire) deduces Bardolph and his brother Bodin from Thorfin, fil. Cospatric -de Ravenswet et Dalton in Yorkshire, temp. Canute; while Watson makes Bardolph the son-in-law, and not the son of Thorfin. Bardolph is “said to be of the family of the Earls of Richmond.” See Gale’s Honoris de Richmond, and Whittaker’s Richmondshire. Burke acknowledges that “the earlier generations of the Earls of Richmond are very conflicting.” The families of CrawI

2 William Claiborne In his old age, when weary of the world and its trouble, he became a monk, and retired to the Abbey, of which he had been a benefactor. (See Dugdale’s and Burke’s Extinct Peerage.) He was succeeded by his son and heir: 2. Akaris, or Acarius FitzBardolph, who founded the Abbey of Fors (5 Stephen, a.d. 1140) and granted the original site of Jervaulx to the Suvignian monks at York. He also gave a charter to the Priory of St. Andrews, and lands and tenths in Rafenswad (Ravenswath), to which gifts “Hen. fit. Hervei,” and Conan d’Ask were witnesses. (Marrig. Charters, Coll. Top. et Genealogy, iii., 114.) He died, a.d. 1161, leaving two sons: I. Herveus, of whom presently. II. Walter. 3. Hervey FitzAkaris (a.d. 1165, ob. 1182), “a noble and good knight,” who consented that ford, L’Estrange, and FitzAUan of Bedale also derive from Bretin Earls; and the FitzHughes, Askews, and others, from Bardolph. Whittaker says, “Askew, Lincolnshire, was granted after 1086 by Alan, Earl of Richmond, to Bardolph, his brother, father of Askaris, ancestor of the Barons FitzHugh of Ravensworth. Henry FitzAskew granted tithes of Askew to IVIarrig, (Burton, Monast. Ebor., 269.) Randolph FitzHenry had Henry and Adam, between whom Askew was divided. Adam assumed the name of Askew.” Hist. Richmond; and The Norman People, 144. Descent

3 Conan, Earl of Richmond, should translate the abbey of charity to East Wilton, and place it on the banks of the river Jore, from which it was called Jorevaulx. He was a witness with his brother Walter to a charter of Conan IV., Duke of Brittany and Earl of Richmond (ii Hen. H., A.D. 1 1 65); and about the same time he “gave his ninth sheaf of com which grew on his lands in Askew, Brompton, Lemingford, and Ravenswet to the Priory of Maryke in the Deanery of Richmond ” (Burton, Monast., Ehor., p. 357). He died, A.D. 1 182, leaving three sons: I. Henry FitzHervey (ob. 1201), who mar. Alice, daughter of Randolph FitzWalter de Greystocke (ob. 12 John, 121 1), from whom descended the Barons FitzHugh. He witnessed a charter of Duke Conan, in 1165, one of Conan de Asch, in 1196; and was a witness, with his brother Alan, to the charters of Peter FitzThornfinn, and Gilbert FitzAlan, 1 196-8. n. Richard. IH. Alan, of whom presently.

4. Alan, dictus “Cleburne” (Le Neve MSS., iii., 114), youngest son of Hervey FitzAkaris, son of Bardolph, “was a witness with his brother Henry (‘Henrico fit. Hervei, Alan fre. ei, Conan d’Aske,’ and others) to charters of Gilbert Fitz- 4 William Claiborne Alan, Alan FitzAdam, and Peter FitzThorfinn, to Marrig Abbey, co. York,” c. 1188-98 {Coll. Top. et Genealogy, iii., 114). Richard Hervei, who witnessed a charter of Ada of Kirby Sleeth (c. 1 196), and “Rich, de Hervei, whose daughter Galiene gave lands in Blencogo to Abbey of Holm Cultram, for maintenance of infirm poor” (N. and B., Hist. West., i., 172-89; Hutch., Hist. Cumb., ii., 331), are probably identical with Richard the second son of this Hervey. Alan, the third and youngest son, received (temp. John) a moiety of the manor of Cliburn, CO. Westmoreland; and a fine was paid for the alienation of lands there in 12 15: “Fin. 16 Joan. m.d. de Terras in Cleburn,” S. V. Lanercost. (See Tanner’s Notitia; Hutchinson’s Hist. Cumb., i., 58.) This manor gave to Alan FitzHervey “a local habitation and a name,” but “when a man takes his surname from his possessions or residences, it is very hard to say at which particular point the personal designation passes into the hereditary surname” (Freeman, Norm. Conq., v., 379). Prior to the Domesday and for nearly two centuries after, there were no fixed surnames; the eldest son took the Christian name of the father, while the youngest as- sumed the name of his own manor; hence “Alan” Descent

5 is found in the charters^ of that period, although the surname must also have been used, for Palgrave states that “Idonea, daughter of Allen Clibburne, married Walter, the fourth son of William Tankard, the Steward of Knaresborough, and had issue George Tankard, who died Sine prole, temp. Henry III.” (1216-72). (See Baronetage, iii., 387; English Baronage, 1741.) 5. Hervey (in Bas Breton, “Haerve” or “Hoerve,” from old German “Hervey,” means strong in war) held lands and tenements in Cliburne, Clifton, and Milkanthorpe, by knight service, tempore. Hen. HI., and Edw. I. (1216-72). There was also a Roland FitzHervy (temp. Hen. HI.) who married Alice de Lexington and held “Sutton upon Trent.” Hervey de Clibume was succeeded by his son and heir Geoffrey (Inq. P. M. 8 Edw. H., 1315).

6. Geoffrery” FitzHervey (de Cleburne), whose heir with Gilbert d’Engayne of Cliburne-Clifton, ‘ Charters: Lord Lindsey says: ” In the eleventh and twelfth centuries the Charters are the only evidence to be depended upon, as history or pedigrees are unsatisfactory or wanting. After this we have the Inquisitions Post Mortem and other authentic records.” See Lives of the Lindseys. ^Geoffrey: This Geoffrey had a brother Nicholas de Clibume, who was Sheriff of Westmoreland, 26, 28, 31, 32, and 33 Edw. I. (1295-1309). Deputy Keeper’s Roll, at the Record Office, London; also Cumh. Westm. Transactions, vol. iv., p. 294. 6 William Claiborne and others, “held divers tenements in Chbume, Louther, Clifton, and Milkanthorpe, by service” (Escheats,

7 Edw. II., 131 5). At another inquisition, temp. Edw. II., “Walter de Tylin, John de Staffel, and Robert de Sowerley [as trustees, probably, in a settlement] held a moiety of Clibume by comage” (CoUins’s Peerage, p. 428). The heirs of Geoffrey, son of Hervey, held by these trustees (by knight service of the king), until Robert de Cleburne, one of the said heirs, became of age, and succeeded to the moiety of Cliburn Harvey. 7. Sir Robert,^ lord of the manor of Cliburn Harvey, was a person of some distinction, temp. Edw, III., and was knight of the Shire of Westmoreland, 7 and 10 Rich. II., 1384-7 {Hist. West., App. i., 459). In 1336 (9 Edw. III.), he was “a witness with Sir Hugh de Louther to settle- ment by Sir Walter Strickland, of the manor of Hackthorp, upon his sons, Thomas, John, and Ralf Strickland” {Hist. West., ii., 92). In 1356 “he held lands in Ireland,” but he apparently made no settlement there. In right of his wife, Margaret, he held the lands and was lord of the » Sir Robert: The knighthood of the age of chivalry was a very different honour from this modem dignity; for in the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries it had precedence of Peerage. Descent 7 manors of Bampton, of Cundale, Bampton Patryke, and Knipe Patric, in Westmoreland. (Inq. Post Mort., 43 Edw. III.; 15 Rich. II., 1370- 92.) He married Margaret, daughter and co-heir of Henry de Cundale^ and Kyne, one of the Drengi of Westmoreland, who held their lands before the Conquest, and were permitted to retain them. This Henry de Cundale was in descent from that Henry, lord of Cundale, who, temp. Hen. II. (i 154), among other principal men of note, was a witness to a compromise between the Abbot of Byland concerning the manor of Bleaton, and in 13 John (12 12) was a witness to a grant of Robert de Vipont to Shapp Abbey; and who in 1201 (Oblata Roll, 2 John) made a fine with the king not to go with him to Normandy. Sir Robert had issue one son, John, who, dying at an early age, was succeeded by his second son, John de Clybourne. I Cundale: Bampton Hall (temp. Hen. IH., 1216-72) was the seat of Henry de Cundale (name derived from “Cundale,” in York), a family of great consideration, who continued here till Edw. II. (1307-27), when their property went to the Clebums. Thomthwaite Hall was the mansion house of Bampton Patric, called after Patric de Culwen, temp. Hen. II., 1154. “Ralf de Cundale was fined 40 marks. ” Fines in Exchequer, 22 Hen. II., 1 176. The battle of Otterbum was fought 1383. Alice, dau. of Thomas Cleburne, temp. Edw. III., married Jno. Wray, from whom the Wrays of Richmond are descended. 8 William Claiborne

8. John de Cleburne (who died vita patris) left two sons : I. Roland; II. John. His widow, Margaret (who married for her second husband John de Wathecoppe of Warcupp), “held the manor of Cliburn-Hervey for Rowland, son and heir of the said John Cleburne and Margaret” (Inq. P. M., 15 Rich. II., 1392; Hist. West., i., 459). Rowland dying young, his lands passed to his brother John. 9. John, second son of John de Clyborne and Margaret, his wife, held Cleburn-Hervy in 1422, 9 Hen. v.: “Johannes Cliburne pro manerio de Cleburn-Hervy, xvi. s. ixd. (Har. I.) MS. 628, ff. 228b). In 1423, he was lord of the manors of Cliburn-Hervey and Clibum-Tailbois (the two moieties having been united after the death of John, only son and heir of Robert de Franceys of Cleburne, who married Elizabeth, daughter and heir of the last Walter de Tailbois: Dugd. MS.); and also “held the manors of Bampton Patrick, Bampton Cundale, and Knype Patric, by cornage” (Inq. P. M. 10 Hen. V., 1423; Hist. West., 257, I., 466). He was succeeded by his son and heir: Descent 9 10. Rowland, son and heir of John de Cleburn, was “lord of the manors of Cliburn-Hervey and Tailbois, and held Hampton-Cundale and Knipe, by homage, fealty and comage” (Inq. P. M. 31, Hen. VI., 1452). He is scarcely mentioned in the local records, though he was probably with Clifford at Towton on that fatal Palm Sunday, 24th March, 1461. He was just and considerate of his tenants, remitted their “gressums”; and by him the last of his “Villeins in gross” was sold free. In 1456 he was appointed “one of the jurors upon the Inquisition, after the death of Thomas Lord Clifford” (34 Hen. VI.; Hist. West., i., 459), and also “held the same which heretofore, as the Inquisition set forth, were held by Ralph de Cundale {Hist. West., {., 466-70). He was succeded by his son and heir:

Workington Hall about 1880

11. John, son of Rowland Cleburne, married Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Thos. Curwen of Workington Hall. This was considered a great alliance, for Elizabeth’s blood was “darkly, deeply, beautifully blue”; her ancestor Orme having married Gunilda, daughter of “Cospatric the Great,” first Earl of Dunbar and Northumberland, whose father Maldred was younger brother of the ‘ ‘ Gracious Duncan, murdered by Macbeth, whose grandmother was Elgira, daughter of the Saxon 10 William Claiborne King Ethelred 11. , called the “unready.” (Jackson’s Curwens of Workington; Symeon of Durham,ii., 307; Freeman’s Norm. Conq., iv., 89.) This John was lord of the manors of Cleburn, and held Bampton-Cundale, of Henry Lord Clifford, by homage, fealty, and scutage, when “scutage” runs at £10 los. ; when more, more; when less, less; and the cornage of 15s. 3d. (Inq. Post Mort. 19 Hen. VII.). Having escaped the bloody fields of Barnet, Tewksbury, and Bosworth, he died (from injuries received in a skirmish at Kirtlemore, onSt. Magdalen’s day, 226. July, 1484), on the 8th Aug., 1489 (Inq. P. M. 4 Hen. VII.), and was succeeded by his son and heir:

12. Thomas, of Cliburne Hall, bom 1467, for at an Inquisition held, 19 Hen. VII. (1504), it was found that “John Clybourne, his father, died 8th August, 1489, and that Thomas Clyborne, his son and heir, was then 22 years of age” {Hist. West., i., 467). He held his manor of Bampton,of Henry Lord Clifford, by homage, fealty, andscutage (Inq. Post Mort., 18 Hen. VIII., 1527), and was assessed for non-payment of his dues onthis manor, due the Diocese of Carlisle, 5 Hen. VIII. {Valor Ecdesiasticus, p. 294). He neglected his estate, engaged in many visionary schemes, and became so wild, reckless, and extravagant Descent ii that in Nov., 1512, “he, with Henry Lord Clifford and others, were proceeded against for debts due by them to the king” (Letters and Papers, Hen. VHL, vol. i., p. 435). He was succeeded by his son and heir:

Edmund Cleburne Male1501

II. Edmund Cleblurne 1501 Married Anne Layton

Children:

Sir Thomas Claiborne the Elder 1525 0r 1530

William Claiborne 1530–1626

Lord Richard Cleborne 1532

Edmund Claiborne Male 1535–

III. Sir Thomas [Cleyborne ]Claiborne the Elder 1530 Married Katherine Reveley

13 passionate man, regarded by some as an “intolerant bigot.” Right royally proud he well might be, for through his great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Curwen, he was descended from that great Cospatric “who sprang,” says Freeman, “from the noblest blood of Northumberland, and even of the kingly blood of Wessex” {Norm. Conq., iv., 89). He was a devoted adherent of the Church of Rome, spent much of his early life in travel; and was probably engaged in some secret negotiations with the French Coiirt, as Lord Gray in his letter to the Privy Council, dated 7th May, 1555, says: “Mr. Clyburn has been a long time in France, and brings important information ” (State Papers, 1553-8). Though warned by his kinsman Sir Henry Curwen (who in 1568 received and hospitably entertained his fifth cousin, the unfortunate Queen Mary, when she arrived at Workington in her flight from Scotland) to * ‘ avoid the numerous plots” at this period, Cleburne engaged in the scheme to release the Scottish Queen, and place her at the head of the “Rising of the North.” How much he was involved in this plot will never be known ; but no doubt he and the Lowthers were “up to the very hilt in treason.” His brother Thomas, a page in the service of his kinsman. Sir 14 William Claiborne Richard Lowther (the custodian of Mary) , doubtless kept him well informed of the secret machinations of the gentry of the north, and he was deep in the counsels of the shrewd and long-headed Gerald Lowther, whom he concealed at Cliburn when pursued by the Warden of the West Marches. Among the State Papers in London is a letter from Richard Lowther, dated 13th Nov., 1569, addressed to the Earl of Westmoreland, alluding to this wily Gerard, and indicating how deeply they were in the plot. “Appoint me one day,” he says, “and I will meet you with four good horses either at Derby, Burton, or Tutbury, there to perform with the foremost man, or die. To the furtherance thereof. Lord Wharton and my brother will join.” On the 14th of May, the Earls made their famous entry into Durham, and, on the 23d of the same month, Mary was removed further south, out of reach of the plotters. On the 28th January following. Sir Francis Leeke wrote to Cecil: “Before receipt of yours for apprehension of Gerald Lowther and Richard Clybume of Clyburne, gentlemen, we had examined some of their servants, John Craggs, and Thomas Clyburne (who had come to town with three geldings of Lowther), about the said Gerard’s movements”;and winds up by saying, “I send this letter for Descent 15 LIFE, that order may be taken for Lowther before he has fled far, as he is not well horsed.” Amid all these troubles,

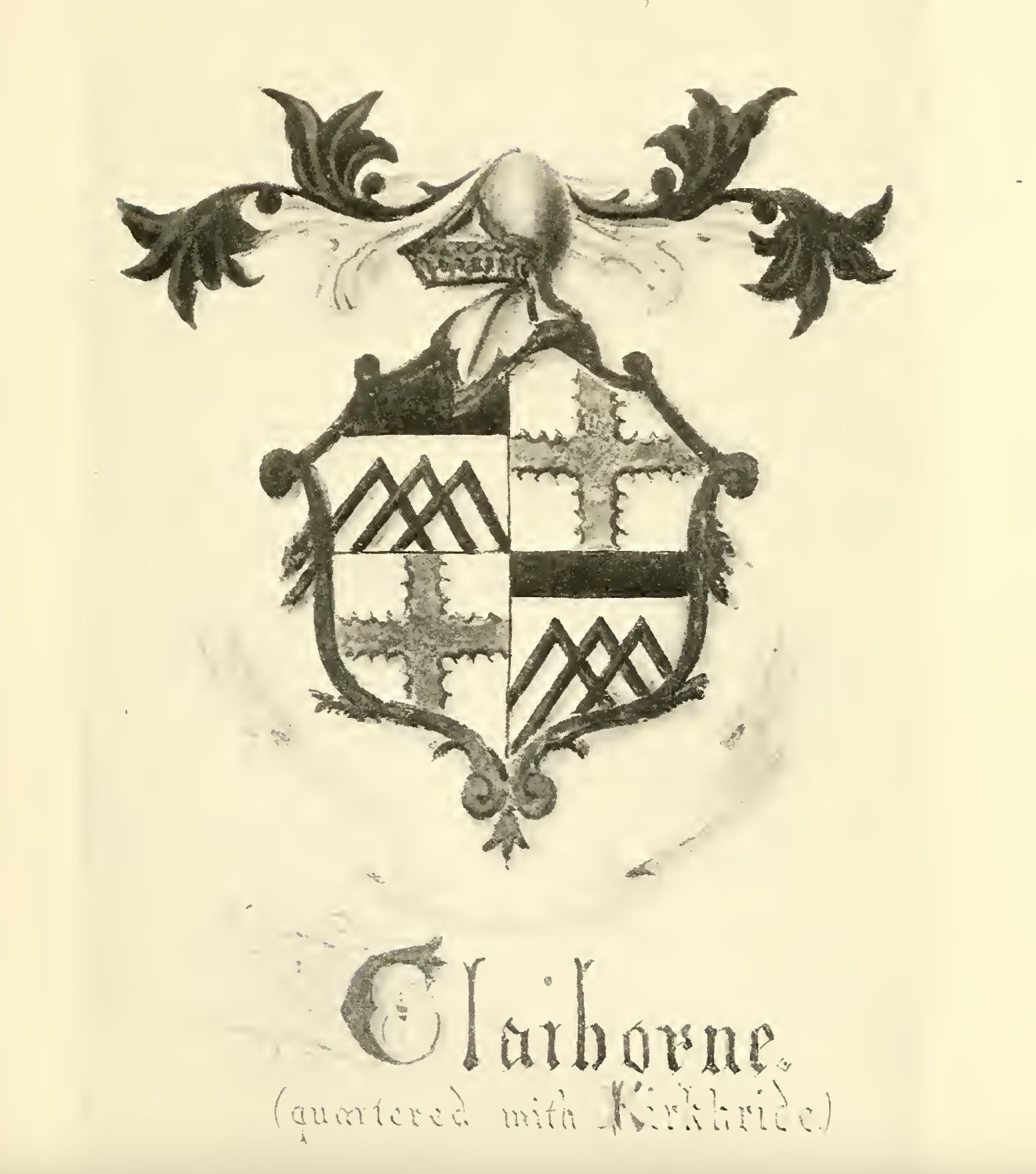

Richard Cleburne was engaged in rebuilding his Hall in the Tudor style. Over the arched doorway he inserted an armorial slab with a curious rhyming inscription in old English characters, now so weatherworn as to be scarcely decipherable (Taylor’s Halls of West., p. 256; Hist. West., i., 460) : “Rychard . Clebur . thus . they me . cawl . Wch . in my . tyme . hath . bealded . ys . hall . The . yeare . of . our . Lord . God . who . lyst . For . to , never . 1567.” On each side of this Tudor archway are two heater shaped shields containing the arms of Cleburne and Kirkbride, and immediately over the inscription a quartered shield; ist and 4th, arg. 3 chevronels braced a chief sable (for Cleborne); 2d and 3d, arg. a cross engrailed vert (for Kirkbride). The extravagance entailed by the rebuilding of the Hall and other improvements led to the mortgage and sale of Bampton-Cundale

(in which parish is the beautiful Haweswater Lake) and of other fair manors which sadly impoverished the Cliburns.

57 1 he was again mixed up with the Lowthers in a plot in which the Duke of Norfolk was a principal, and in which the latter lost his head, when all these ambitious schemes came to an untimely end. Full of intemperate zeal for his religion, Cleburne continued to make himself obnoxious to Rokeby Walsingham, and Leicester, “who thoughtit pious merit to betray and ensnare those eminent persons who were not yet quite weaned from the Church of Rome” {Hist. Cumh., i., 387). By them he was closely watched and persecuted, andwas several times indicted and imprisoned in the”Fleet.” Accused by Rokeby^ of being a “Recusant,” and of being “carried away with blind zeal to favour and hold with the Romish Church”(State Papers, 1581-90, vol. clxxxiii., 207); and harassed by his affairs, his health gave way, and in 1577 he was obliged to spend six months at Bath. In October, 1584, he was so completely broken down that Rokeby declared him to be”aged, infirm, and sickly,” and again “he had permission to repair to Bath, where he remained from 30th January to the ist May, 1586, on account of his health” (State Papers, p. 207-303). By his wife Eleanor, granddaughter of NicholasHarrington, of Enbarry Hall, and daughter of ^Rokeby: Anthony Rokeby the “spy” (in 1568) was set to watch his movements. Descent 17 Launcelot Lancaster, of Sockbridge and Barton (eighth in descent from Roger of Barton, ob. 1290, who Nicholas says was “a brother of the half blood to William de Lancaster, last Baron of Kendal, ob. 1246, to whom the said William gave Barton and Patterdale, styling him in his charter ‘Rogero fratre meo'”—MSS., Denton and Lancaster Pedigree),

Sir Thomas [Cleyborne] Claiborne the Elder 1530 had issue two sons and seven daughters:

II. Edmund, of whom presently.^ ‘ Some confusion exists in regard to the title of Edmvind Clibume, the father of William Claiborne. He has been referred to as Sir Edmund Cliburne by a number of writers. The only knight who bore the title of Sir in the entire family, according to O’Hart, was Sir Robert de Clibum, the seventh from Bardolph, in the time of Edward III.; he was known as “Knight of the Shire of Westmoreland.” That title of Sir was not an hereditary one, and could not be transmitted. It was won on the field of battle or through service to the Crown, and may truthfully be said to have been the greatest honour a gentleman could win. Sir Robert, like all the rest of the family who held Clibvun-Hervey, and the other possessions of the family, was known as Lord of the Manors of CUbume, etc., but this title was not one of knighthood; it was one of cotutesy by reason of possessions. The transmitted title of knighthood arose much later. Edmund Clibume, the father of William, was simply known as heir of Richard Clibume and Lord of the Manors of Clibume and Killerby. Admiral C. J. Clebome was accustomed to tell the writer that the family of Clibume belonged simply to the landed gentry, and was classed amongst the Barones minores, as opposed to the Barones majores, amongst whom were the Earls and Dukes; in short, they were simply Gentlemen. [8 ]…

prominent member of the Virginia Company William Cleborne was made Surveyor, and SecreIt will be remembered that the Black Prince, for example, won the golden spurs of knighthood at the battle of Poitiers. Neither King nor Prince could wear them until they were won. Knighthood was an institution which marked the noblest democracy of all time—the democracy of self-sacrifice, courage, and service. (J. H. C.) Descent 19 tary of State for that Colony, in 1626. Edmund was devoted to the pleasures of the chase and passed most of his time at Killerby, preferring the Yorkshire dales to the cooler breezes of Westmoreland. He had a grant from the Crown, of the Rectory and Parsonage of Bampton, Westmoreland, and also had some interest in the Rectories of Barton and Shelston. There seems to have been some trouble about Bampton, for he had a suit-at-law with Sir Rowland Hunter (clerk), defendant, about a claim on that Rectory which had been granted to Cleburne by letters patent (see Chancery Proceedings, Eliz., i., 151). By his wife Grace Bellingham (bom 1558, ob, 1594), who had for her second husband, Gerard, second son of Sir Richard Lowther, …???????

his younger brother was Robert; he likewise had two sisters, Agnes and Dorothy, the latter “somewhat of a shrew.” Thomas, who succeeded Edmund, was bom1580 and died 1640. He was the seventeenth in line from Bardolph, but the fourteenth Lord of the Manor, counting from Alan, the first. He is said to have been indolent, shy, and melancholy. He found his estates much en- cumbered and was forced to mortgage his lands. Thomas lived a retired and quiet life at Clibum and Killerby, cultivating and improving his lands. He took but little interest in affairs of state, and lived in contentment with his loving wife, Frances, the daughter of Sir Richard Lowther, already referred to.[I cannot find proof of this.]

Thomas had three sons, Edmund, Richard, and William. William [this would have been william of virginia’s uncle

settled in Ireland and became the founder of the BallycuUitan Castle Cliburns. He was known as “Wise William of Ciallmahr.” He went to Ireland with his uncle. Sir Gerard Lowther, where he became known far and wide for his humanitarian qualities, as the arbitrator of the disputes of his neighbours and as the friend and adviser of the poor. He purchased his possessions to wit: “From Capt. Solomon Cambie, the castles, towns, and lands of BallycuUitan, the villadge and lands of Bunnadubber and of Killinbog >5C5^”K®n£pCS:ifi<afeM^i4<^£^sS

THOMAS CLIBURNE, OF CLIBURN HALL, WESTMORELAND, AND KILLERBY, YORK. ELDEST BROTHER OF WILLIAM CLAIBORNE From a painting in possession of Major W. C. C. Claiborne. Original said to have been in possession of Sir John Lowther??????

CHAPTER II

CLEBORNE OR CLEBURNE, OF CLIBURN, COUNTY WESTMORELAND; HAYCLOSE, COUNTY CUMBERLAND; KILLERBY, COUNTY YORK; ST. JOHN’s MANOR, COUNTY WEXFORD; AND OF BALLYCULLITAN-CASTLE, COUNTY TIPPERARY; VIRGINIA A RMS:

On a field argent, three chevronels braced in base sable, a chief of the last. According to O’Hart: This ancient and knightly family may be traced in the male line to the early part of the 11th century; and, on the “spindle” side (through the Curwens) to the Scoto-Pictish and West-Saxon Kings. It derived its surname from the Lordship of Cliburne, in Westmoreland, but the early descent of the manor is involved in obscurity, owing to the destruction of northern records in the border wars and feuds of the 1 2th and 13th centuries. The first record of the name appears in the Domesday or Great Siirvey of England, A.D. 1086, vol. i., p. 234. (See Jackson’s Curwens of Workington Hall; Symon of Durham; and Freeman’s Norman Conq., iv., 89.)[ pg. 24]

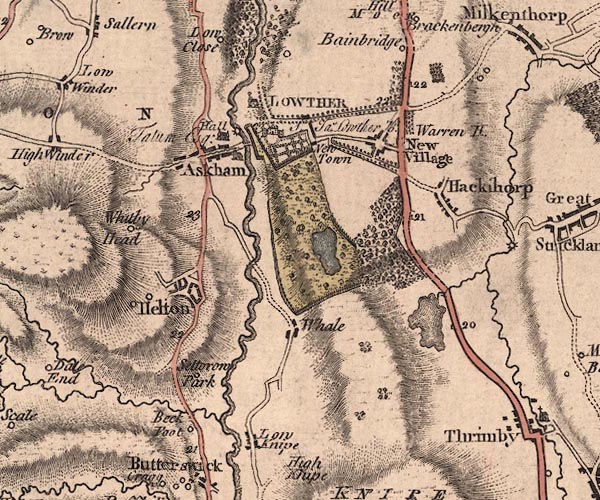

Cliborne is pronounced “Clebburn.” The name is spelled in over thirty different ways, and is often confounded with Glyborne, Clabon, Claybough, Clayburgh, Giberne, Caborne, and other entirely distinct families of diverse origin. The word Cliborne is derived from the Anglo-Saxon ” Claeg ” : sticky earth, and ” borne ” : a stream. Danish, ” Klaeg ” : clammy or sticky mud. Ferguson derives it from A-S “clif “: a hill, and “burne”: a stream. And Picton, from Norse or Danish, ” Klif- brunnr”: the Cliffstream (compare “Klifsdabr”; Cliffdale). In the time of Edward the Confessor, Cliburn contained but ten carucates or 1200 acres. At the Survey there were 1440 acres; and by modern measurement it embraces 1360 acres, or ten miles in circumference. It is situated on an eminence on the Leith riviilet, about six miles from Penrith, and is bounded, E.-S.-W. by the Parish of Morland, and north by Louther, Clifton, and Bingham. Ridpath and others state that the greatest part of Carlisle perished, and the records of the North suffered by fire in 1173; and again in 1292, when the principal records and charters of the North were destroyed. Nicholson, the historian of Westmoreland, says : “The Manor of Cliburne was early divided into two moieties or halves, Cliburn-Tailbois and Cliburne-Hervey ; the first half derived its name from the Tailbois, the Barons of Kendal; CliburnHervey in like manner.” 26 William Claiborne As has been seen in the pedigree of Colonel Wm. Claiborne, the third in descent from Bardolph was Hervey or Herveus FitzAcaris, and the natural deduction would be that the moiety of ClibumHervey derived the latter half of its hyphenated name from Herveus, the son of Acaris and grandson of Bardolph. But it seems that the matter is not so simple after all, for O’Hart discusses it at some length. He says: “Though the antecessors of Hervey in Cliborne are not known, Cliborne, as a man’s name, occurs as a donor of houses in York to the Priory of Nastel, a.d. i 120.” He says further, “The founder of the family was, undoubtedly, a Norman or Breton Hervey, after whom a moiety of Cliburn was named,” but he is in doubt whether this Herveus was a cadet of the great Feudal Baron of Vesci, or of the equally powerful house of Acarius of Ravensworth. (Senhouse, Somerville MSS.) That he was of the latter, that is, the house of Bardolph of Ravensworth, it is my purpose to set forth presently proofs which appear convincing. Both families held lands in the immediate vicinity of Englewood, and in both the Christian names of Hervey, Geoffrey, Robert, and William occur. By reference to the pedigree of William Claiborne in descent from Bardolph, it will be seen that Cleborne of Cliburn 2^ Hervey de Clibume was the son of Alan, that Geoffrey de Cliburne was son of this Hervey, but that the name Wiliam does not appear in the pedigree, as set forth by O’Hart, till William Cliburne, fourth son of Edmund, fourteenth Lord of Cliburn, was born; and then not again till the birth of William Claiborne, the subject of this sketch, in 1587. This is only presumptive evidence in favour of the descent of the family from Bardolph. But it appears to the writer that there is still more evidence, conclusive, in fact, and that evidence lies in the sameness, with “differences,” in the arms of Cliburn and other families deriving from the same source. According to O’Hart, the families of FitzHugh, Askew, and others derive from Bardolph, and Whittaker says: “Askew, Lincolnshire, was granted after 1086 by Alan, Earl of Richmond, to Bardolph, his brother, father of Acaris, ancestor of the Barons of FitzHugh of Ravensworth” (History of Richmond and the Norman People). It has been noted that Henry FitzHervey, the eldest son of Hervey FitzAcaris, was the eldest brother of Alan de Cliburne, and that this Henry FitzAcaris was the ancestor from whom the Barons FitzHugh descended. Moreover, the arms of 28 William Claiborne Cleborne are clearly FitzHugh, and Ravensworth, the seat of the latter family, is within twenty miles of Cliburn. In ancient times, “arms” could not lie and sameness in arms in families indicated a sameness in origin. The arms of Cleburne, as stated, are: On a field argent, three chevronels interlaced in base sable, a chief of the last, and those of FitzHugh: on a field azure, three chevronels interlaced in base, or, a chief of the last. The so-called differences are simply modifications in arms and are created by the College of Heraldry. It is obvious even to one not learned in Heraldry, that the arms of Cleburne and FitzHugh are the same in origin. Hence they must have been borne by men of a common ancestry. There is still more proof, however, which may be described as contributory, in the matter of Christian names. In the period to which reference is made, there were no surnames as there are to- day, but a son was given a Christian name, and Fitz (meaning, son), followed by the name of his father, was added, to show his descent ; for example : Akaris FitzBardolph was the son of Bardolph, in like manner, Hervey FitzAcaris was the son of Acaris. The Christian name of a son was generally that Cleborne of Cliburn 29 of his father, another direct ancestor, or a collateral one, and we observe in the name of Alan de Cleburne, for example, a reversion on the part of his father, Hervey, to Bardolph’s brothers, Alan Niger or Alan Riifus (or Black Alan and Red Alan). These two, as has been seen, were the second and third sons of Eudo, and elder brothers of Bardolph. Alan continues the custom by naming his son Hervey, in honour of his father, Hervey FitzAcaris; Hervey, in like manner, names his son Geoffrey, in honour of the fourth son of Eudo, Geoffrey, another elder brother of Bardolph. This custom has continued to the present day, and is not restricted to those of English descent. All these things furnish conclusive proof that the family is descended from Bardolph, the last and seventh son of Eudo, the youngest brother of Alan, first Duke of Richmond. O’Hart finally arrives at the same conclusion, since he derives the descent of the family from Bardolph. The way in which the manor of Cliburn-Hervey came to Alan is a matter of some speculation. Watson Holland (Somerville MSS.) says a moiety of Clibume came to Hervey in marriage through the Viponts, who in turn derived it from the hereditary Foresters of Englewood. O’Hart thinks 30 William Claiborne this a more reasonable explanation than that it descended through Alice, granddaughter of Walter Fitzlvo, who married Henry FitzHervey of Ravensworth, who in turn may have enfeoffed Alan de Cleburne. It appears to the writer that the latter explanation is more reasonable than the former, if this Henry FitzHervy of Ravensworth was, as it appears, the elder brother of Alan de Cleburne, Again, O’Hart suggests that “Meaburn Regis,” the property of Sir Hugh de Morville, together with all his other possessions, fell into the King’s hands by reason of the complicity of Sir Hugh in the murder of Becket; the King granted these forfeited lands to Robert de Vetinpont, who may have enfeoffed Alan FitzHervey (Alan de Cleburne). Again O’Hart suggests that, while the forfeited estates of Sir Hugh de Morville were in the hands of King John, the Crown may have enfeoffed Alan, or he may have been enfeoffed by De Morville before his lands passed to the Vetinponts. Of all these explanations, the most reasonable to the writer is, that Henry FitzHervey of Ravensworth, eldest brother of Alan, enfeoffed Alan with Cleburne from his large possessions in the North, brought him by Alice, granddaughter of Walter Cleborne of Cliburn 31 Fitzlvo, in marriage. However all this may be, Hervey and his descendants held the Manor of CHbum-Hervey by ‘ ‘ Knight service of the Crown ” (CoUins’s Peerage, p. 426) and by “Cornage” only of the Viponts and Cliffords, and Alan dictus Cleburne (Le Neve MSS., iii., 114) certainly re- received (tempore John) a moiety of the manor of Cliburn, County Westmoreland, thus acquiring “a local habitation and a name,” but as Freeman {Norman Conquest, v., 379) says, “when a man takes his surname from his possessions or residence, it is very hard to say at what particular point the personal designation passes into the hereditary surname. Alan, being the youngest son of Hervey FitzAcaris, was probably, after the manner of younger sons in England even to this day, lacking in this world’s goods, and having been enfeoffed by someone, was thereafter known as Alan de Cleburne. This Alan was the first who bore the name of Cleburne, The use of the prefix de in the name persisted for centuries, but was finally lost and certainly was not used by Col. William Claiborne, the first representative of the family in America. The name of the parish in England today is spelled Cliburn, likewise that of the old Hall. In Ireland, the name is spelled by the family of Moate 32 William Claiborne Castle, Clihhorn, by the descendants of William of BallycuUitan, Cleborne, and sometimes Cleburne, by others Clibburn, and by the Virginia branch, the descendants of Col. William, of Jamestown, Claiborne. The patronymic of the father of William Claiborne was spelled Cliburne, according to O’Hart, and why Col. William should have changed the spelling to Claiborne is not shown. His signature in the records in Virginia, and on his petitions to Charles the First, is spelled, Claiborne, and all his descendants in this country have retained it as he wrote it. It is the same name however spelled and all the people who bear it are doubtless of the same origin. It is a name hoary with age and has ever been noble and honourable. [pg. 32]

CHAPTER III

Image Credit Geograph

CLIBURN CHAPEL, OR CHURCH, AND CLIBURN HALL CLIBURN CHURCH is Norman in structure and is situated within a stone’s throw of the Hall. It is mentioned by Grose amongst the antiquities worthy of notice in Westmoreland. It was dedicated to St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, and marks one of the resting places of the Saint’s body as the remains were borne by monks on their shoulders in their flight from Holy Island, to escape from the Danes in 873. Singular to relate, there is no mention of the church in Domesday, but, as has been remarked, this is no evidence or proof that it did not exist, when the Survey of the North was compiled by William’s command. O’Hart thinks it was probably built by Orme, or a Baron of Kendal, in the early part of the eleventh century’, and was granted to St. Mary’s at York. Owing to the care, interest, and generosity of its former and deceased Rector, the Rev. Mr. Clarke Watkins Burton, M.A., it is, or was several years ago, in excellent preservation. There is, in the chancel, a handsome mural tablet to the memory of Sophia Portia Burton, daughter of Sir William Pilkington, of York, first wife of the Rev. Mr. Burton. On the north side is a small Norman window, one of those curious “leper windows,” through which lepers used to look on the blessed sacrament, in the ancient days of the Roman Church in England. This window is now filled with stained glass in memory of Cuthbert Lowther Cleborne, a son of Admiral Christopher J. Cleborne, U. S. Navy. The writer has twice visited Cliburne, once in 1886, as he was returning home from his medical studies in Europe, and again several years ago, after his marriage, in company with his wife, likewise a descendant of William Claiborne, through her father. Major W. C. C. Claiborne of New Orleans. The church is more nearly what we in America would denominate a chapel, and has from time to time, through the ages, been repaired, till presumably not one stone of the original structure remains. The floor of the church at present consists of a single very large flagstone, taken from a quarry in the north of England. It has Cliburn Chapel arid Hall 35 been presumed that the remains of all the Clibumes lie underneath the flooring of the church or did lie there, for, though the family lived at Cliburn from the days of Alan, approximately 1188, to the days of Timothy, the last of the name in England, 1 630-1 660, there is no stone or monument or inscription to mark the place where any one of the name of Clibume was laid to rest. Admiral C. J. Clebome, U. S. Navy, now deceased, to whom the writer owes many things and whose memory is held in affectionate remembrance, wrote and told him personally there was a tradition in the family, that the Bishop of Knype, circa time Henry VIII., a relative of the Cliburnes, ciu”sed them by bell, book, and candle, for their apostasy from the Church, in a doggerel verse in Old English, which he sent him, but which, by unhappy chance, has been lost from amongst his papers. The writer remembers the curse ran that for the ‘ ‘ apostacie and heresie with which they were accurst, ” their race should perish forever from Clibume, and not a stone should be left to mark the place where they and their ancestors had lived. It is singular and worthy of remark also that no one by the name of Cliburne has lived at the manor or on the demesne since 36 the death of Timothy, the last of the direct line. The curse seems to have come true.

The place Cliburn can only be described as a hamlet, composed of fifty or sixty cottages, mostly thatched, and located on a road, which runs through it and from the railway station. They seem to be of great antiquity in general. Just before one arrives at the hamlet, on the way from the station, one finds on the right of the road, the Rectory, formerly occupied by the Rev. Mr. Burton, already referred to, and his family. The writer cannot forget the ready and cordial hospitality which he received at the hands of this reverend gentleman, his charming wife, and daughters. When the writer presented himself at the door, it was opened by Mr. Burton, who was a picture of an English squire and country gentle- man. On the visitor’s stating who he was and his object in visiting Cliburne, namely, to see the home of his ancestors, the Rector thrust out his hand, saying, “Welcome, my boy, come in,” and leading him into the drawing-room, presented him to his wife, who was on her knees on the floor playing with her youngest daughter, a type of an English child. She received him as if she had known him always, with a cordiality and simplicity which up to that date he had seen only in his Cliburn Chapel and Hall 37 Virginia home. In fact, it was Virginian hospitality, because it was English hospitality. He thinks this incident worthy of mention in these notes, and he was surprised and flattered to know that these strangers accepted him on his own recognizances as the individual he professed to be. The Hall, at present, with the surrounding ground, is the property of the Earl of Lonsdale, whose family name is Lowther. Lord Lowther is related to the family of Cleburne, by reason of the marriage, in 1574, of Frances, the daughter of Sir Richard Lowther, [???????]the Sheriff of Cumberland, to Thomas Cliburne, the eldest brother of Col. William Claiborne of Jamestown, Va., and son of Edmund Cleburne, Lord of the Manors of Cliburne and Killerby. The manor was built by Richard Cleburne in the Tudor style in 1567, on the site of an earlier structure or on the foundations of the ancient fortalice, or “pele of Cliburn.” When the writer was there in 1886, the donjon or keep was still in a state of preservation, and the winding stone stairs that led from it up to the ” battlemented parapet” were open; but, on his last visit, several years ago, he was surprised and mortified to find that the stairway had been blocked with brick and mortar. The battlements 38 William Claiborne had already been removed at the time of his first visit. Taylor, in his Manorial Halls of Westmoreland, says, it must, in the time of Richard Cleburne, have been a place of very considerable importance, but the writer can affirm without fear of contradiction, that, whatever it may have been, its glory is departed now. As it is approached from the road, one enters the courtyard, which is in the form of a parallelogram, with the Hall at one of the smaller sides. Surrounding or flanking the yard are a number of lofts or stalls, which must at one time have been capable of storing much provender and furnishing accommodation for a large number of horses. The yard is paved with stones, and over the doorway of the Hall, cut in red sandstone, are the arms of Clebtune, quartered, with those of Kirkbride; underneath these is written, in Old English characters, the rhyming inscription, now fast wearing away, referred to in the pedigree, under the caption of “Richard the Martyr.” In a field, to the rear of the Hall, stand two old oaks, gnarled, twisted, and decaying. Admiral Cleborne told the writer they were the sole remaining giants of the ancient Forest of Englewood. They are of interest, since they suggest the story told by the Admiral touching a tradition about the Cleburne crest. He said, in very ancient times, when the Forest of Englewood was thick and flourishing, one of the Lords of the Manor, returning home late one evening, was caught in a thunderstorm in the Forest. As he was riding fast through the Forest, a thunderbolt struck a tree, and a limb of it, in falling, was on the point of knocking him from his horse, but, at that moment, a wolf ran out of the brush and, frightening the horse, caused him to shy, so that the limb fell short, and the horseman was unhurt. From this incident the Wolf is said to have been taken as the family crest, and it has so remained to this day; at least, it is the crest used by Colonel William and that which most of the branches of the family in Virginia have used. Since Colonel William was the second son of Edmund, his crest is a demi-wolj, and is described as rampant reguardant, ppr., which latter abbreviation signifies proper or natirral colour. Mr. William Cleburne of Omaha, if alive, alone is entitled to the whole wolf. Another tradition claims the Wolf was derived from “Hugh Lupus, Lord Paramount of Cleburne and other lands, but the incident related furnishes the more interesting explanation. 40

Like the crest, the motto is a variable thing, and can be modified or changed. Colonel William used the Saxon words, “Lofe Clibbor na scaeme, which means, “tenacious of what is honourable and praiseworthy, and not of what is shameful.” Admiral Cleborne thought Colonel William probably adopted this motto in America to indicate his attitude in his contention with Lord Baltimore, in the matter of the possession of Kent Island. The Hall viewed from the side of the two oaks is, to the writer’s mind, more attractive than when viewed from the courtyard. At the rear is a terrace with steps, and from this vantage point a good view of the surrounding country can be obtained, particularly of the rivulet, brook, or run, called the Leith. This small stream runs over a bed of clay—hence the name Clibum, or Claystream. Just below and to the right of the terrace is the doorway to the kitchen. Over the doorway the arms, unquartered, are cut. A horse could easily enter through it. The kitchen is very large, and the fireplace, now occupied in part by a modem range, is the largest the writer has ever seen. It appeared to be out of all proportion to the possible needs of the household. The walls are exceedingly thick; they were found, on measurement, to be of the thickness of the length of an umbrella the writer had in his hand. The measurement was made at the embrasure of one of the windows. This has some bearing on the originally defensive character of the structiu-e, as O’Hart has suggested that the present Hall was built on the foundations of the ancient pele of Cliburn. A pele was a round turreted structure, rather peculiar to the North Country and was both a dwelling and a place of defence. One of these towers still stands at Clifford, not far from Clibume Hall. It consists of a single tower, and is entered below by a door flush with the ground. These peles were used by the North Country gentry to repel and defend themselves against the inroads and attacks of the cattle-stealing, aggressive Scots, who lived just over the Border, called the Marches. It is said the Cliburnes were constantly engaged in the Border warfare and were required to furnish men, like all families on the Border, to this end. This tradition is likewise consistent with the preexisting turrets on the manor, the donjon keep, and the winding stairs leading from it to the turrets on the roof. The country around Clibume reminds one of the Valley of Virginia, especially the region of Clarke County. The stone fences are constructed 42 William Claiborne like those in the valley; the ground is in the same high state of cultivation, the country is rolling, and if one were transplanted suddenly from one place to the other, it would be difficult to recognize the difference between the two. The view from Cliburne Hill, as one goes up from the station, and looks back toward the distant hills is indeed peaceful, tranquil, and sweet. The writer felt as much at home there, as he does in the Valley of Virginia. Even the country people resemble those in Virginia, down to the broad osier hats trimmed under the brim with green, and the trousers stuffed in the boots. The respect that homogeneous English people have for traditions and blood kinship, guaranteed to the writer, as he does not doubt it would guarantee to others of the blood, a cordial and friendly reception in the houses of both the gentle and humble of the parish. The glory of the old place is departed and only ghostly memories haunt it, but Cliburn Hall, Cliburn Church, and the hamlet of Cliburne are well worth a visit. It is regrettable that no one of the family is willing or able to purchase the Hall and preserve it from the destruction into which it is fast falling.

CHAPTER IV DRAMATIS PERSONS

IN 1587, Sir Walter Raleigh founded the Colony of Croatan in North Carolina. Bartholomew Gosnold, who was a member of that expedition, on his return to England, induced the fitting out of another to America. Sailing down the northern coast of the country which is now New England, he came to Virginia. Being moved by the character of the land and its approaches, he brought about, on his return to England, the founding of the original London Company in 1606. The Company was formed under a charter granted by James I., to settle and develop by trade English America along the Atlantic Coast, running one hundred miles inland and extending between latitudes 34°-4i °, which is to say, from the Hudson River to the southern limits of North Carolina. He, likewise, induced the formation of the Plymouth Colony, north of this region a matter with which this sketch is not concerned. 43 44

In 1609, the original London Company was rechartered under the name of the Virginia Company. It embraced territory which extended two hundred miles north and two hundred miles south of Old Point Comfort, at the mouth of the James River, and to reach “up into the land from sea to sea.” But, in 1612, the colonists begged and secured a new charter, which included the Bermudas. Up to this time the London Council had governed Virginia, but by this charter the control of the Colony was put into the hands of the stockholders of the Company, who numbered about nine hundred important and wealthy citizens of England, amongst whom were some fifty noblemen and one hundred and fifty baronets, or knights. The period at which this last company was formed marked the beginning of the long struggle of the English people for government by a free Parliament, as opposed to the absolute rule of kings. The stockholders were divided into the Country Party and the Court Party. The former were independents, free and bold thinkers who sought for free things for the government of Virginia, and were decidedly in the majority. The minority, [44] or Court Party, held for absolute government by the King. On the 30th of June, 1619, the first session of a legislative body in America was held—that of the Virginia House of Burgesses. On July 24, 1 62 1, the Virginia Colony was granted a written Charter by the Virginia Company, whereby free government was conferred upon them {Claiborne and Kent Island in American History, by DeCoiu-cy W. Thorn, Eastern Shore Society of Baltimore City, 1913)- Such was the Colony of Virginia, such its area, and such its character of government when William Claiborne, a member of the Country Party sailed from England for the New World. William Claiborne was bom in 1587; it is not known with certainty whether at Cliburn in Westmoreland or at Killerby, another estate and hunting seat of the family in York. His boyhood and young manhood were passed between these two places. When about thirty-three or thirty-four years of age he went up to London, to seek some means of future livelihood, and made the acquaintance of Capt. John Smith, the Virginia pioneer. It would appear that he and Smith became good friends, for later on John [45] Smith named a group of islands, outside of Boston, “the Claiborne Isles.” It is not unlikely he received from Smith the inspiration to seek his fortunes in Virginia. It seems quite certain he came to Virginia in the ship George, with Sir Francis Wyatt, in 1621-22. Being the second son of Edmund Cliburn, Lord of the Manor of Cliburn and Killerby, and doubtless being, like most younger sons of English gentlemen, not possessed of much of this world’s goods, he must needs win his own fortune. As subsequent events amply show, he possessed qualities that are worth more than inheritance and broad acres. He appears, therefore, in that year of grace 1621, to have taken heart and girded on his sword for conquests in the New World, in the Colony of Jamestown, in the “Kingdom of Virginia.” He is found possessed, on sailing, of the post of Royal Surveyor for the Colony. It has been a matter of some speculation to several writers how Claiborne obtained this post. As O’Hart remarks, his position in the Colony in the above-mentioned capacity was obtained, probably, through the influence of Anne, Duchess of Pembroke and Dorset, whose husband was one of the London Company, and who was a connection of his mother, Grace Bellingham, second [46] daughter of Sir Alan Bellingham. Doubtless, much of the personal influence he had with the King in after years was obtained through this source likewise. Armed with such credentials, his education, superior to that of most of his contemporaries in Jamestown, according to several writers, his intelligence, capacity, and persistence, it is not surprising to know that, as Fiske says, he prospered greatly, acquiring large estates and winning the respect and confidence of his fellow-planters.

About 1627, five or six years after his arrival, he started trading with the Indians, on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay, the Potomac and Susquehanna rivers. Such barter and exchange must naturally have been very profitable, since with such trifles as beads, hatchets, etc., one could purchase furs from the natives, ship them to England, and fetch high prices. These seem to have been the first acts that led to his remarkable career. But his broad mind and ambition took in greater territory still ; indeed, the Delaware and Hudson rivers, New England, and even Nova Scotia itself. To this end he directed the attention of William Cloberry, a wealthy London merchant, to the advantages to be derived from such trade with the [47] Indians. This Cloberry had already traded with Canada, and with other merchants had a patent to trade with Guinea in Africa. It seems that Claiborne was in England at the time called Cloberry’s attention to the profits to be obtained from traffic with the Virginia Indians, for we find that a company was forthwith formed there, composed of Wm. Cloberry, MauriceThompson, Simon Turgis, John Delabarr, and Wm. Claiborne, six shares in all, Cloberry holding two and the others one each. Probably through the above-mentioned court influence Wm. Claiborne obtained from KjngCharles I. a royal license to trade and make discoveries “in any and all parts of North America not already pre-empted by monopolies” (Fiske). It is well to cite the wording of this license, as it bears importantly on the contention that existed for many years between the actors in the drama that is to follow: Charles, by the grace of God King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, etc.

Whereas our trusty and well-beloved William Cleboume, one of our councell and Secretary of State from our Colony of Virginia, and some other adventurers with him have condescended, with our trusty [48] and well-beloved councellor of both kingdoms, Sir William Alexander, our principal secretary for our Kingdome of Scotland, and others of our lovinge subjects, who have charge over our colonies of New Scotland and New England to keepe a course for interchange of trade amongst them as they shall have occasion. As also to make discoveries for increase of trade in those parts, and because wee do very much approve of all such worthy intentions, and desirous to give good encouragement to these proceedings therein, being for the relief and comfort of those our subjects and enlargement of our dominions, these are to license and authorize the said William Cleburne, his associates and company freely and without interruption from time to time to trade and traffic of corne, furs or any other commodities whatsoever with their shipps, men, boates and merchandise in all sea-coasts, rivers, creeks, harbors, land and territories in or neare those parts of America for which there is not already a patent granted to others for trade. There are several points to be made in the consideration of this license.