“The application of flowers and plants to ceremonial purposes is of the highest antiquity. From the earliest periods, man, after he had discovered

“What drops the Myrrh and what the balmy Reed,”

offered up on primitive altars, as incense to the Deity, the choicest and most fragrant woods, the aromatic gums from trees, and the subtle essences he obtained from flowers. In the odorous but intoxicating fumes which slowly ascended, in wreaths heavy with fragrance, from the altar, the pious ancients saw the mystic agency by which their prayers would be wafted from earth to the abodes of the gods; and so, says Mr. Rimmel, “the altars of Zoroaster and of Confucius, the temples of Memphis, and those of Jerusalem, all smoked alike with incense and sweet-scented woods.” Nor was the admiration and use of vegetable productions confined to the inhabitants of the old world alone, for the Mexicans, according to the Abbé Clavigero, have, from time immemorial, studied the cultivation of flowers and odoriferous plants, which they employed in the worship of their gods.

“But the use of flowers and odorous shrubs was not long confined by the ancients to their sacred rites; they soon began to consider them as essential to their domestic life. Thus, the Egyptians, though they offered the finest fruit and the finest flowers to the gods, and employed perfumes at all their sacred festivals, as well as at their daily oblations, were lavish in the use of flowers at their private entertainments, and in all circumstances of their every-day life. At a reception given by an Egyptian noble, it was customary, after the ceremony of anointing, for each guest to be presented with a Lotus-flower when entering the saloon, and this flower the guest continued to hold in his hand. Servants brought necklaces of flowers composed chiefly of the Lotus; a garland was put round the head, and a single Lotus-bud, or a full-blown flower was so attached as to hang over the forehead. Many of them, made up into wreaths and devices, were suspended upon stands placed in the room,

garlands of Crocus and Saffron encircled the wine cups, and over and under the tables were strewn various flowers. Diodorus informs us that when the Egyptians approached the place of divine worship, they held the flower of the Agrostis in their hand, intimating that man proceeded from a well-watered land, and that he required a moist rather than a dry aliment; and it is not improbable that the reason of the great preference given to the Lotus on these occasions was derived from the same notion.

This fondness of the ancients for flowers was carried to such an extent as to become almost a vice. When Antony supped with Cleopatra, the luxurious Queen of Egypt, the floors of the apartments were usually covered with fragrant flowers.

When Sardanapalus, the last of the Assyrian monarchs, was driven to dire extremity by the rapid approach of the conqueror, he chose the death of an Eastern voluptuary: causing a pile of fragrant woods to be lighted, and placing himself on it with his wives and treasures, he soon became insensible, and was suffocated by the aromatic smoke.

“When Antiochus Epiphanes, the Syrian king, held high festival at Daphne, in one of the processions which took place, boys bore Frankincense, Myrrh, and Saffron on golden dishes, two hundred women sprinkled everyone with perfumes out of golden watering-pots, and all who entered the gymnasium to witness the games were anointed with some perfume contained in fifteen gold dishes, holding Saffron, Amaracus, Lilies, Cinnamon, Spikenard, Fenugreek, &c.” Folkard. Plant Lore, Legends, Lyrics.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

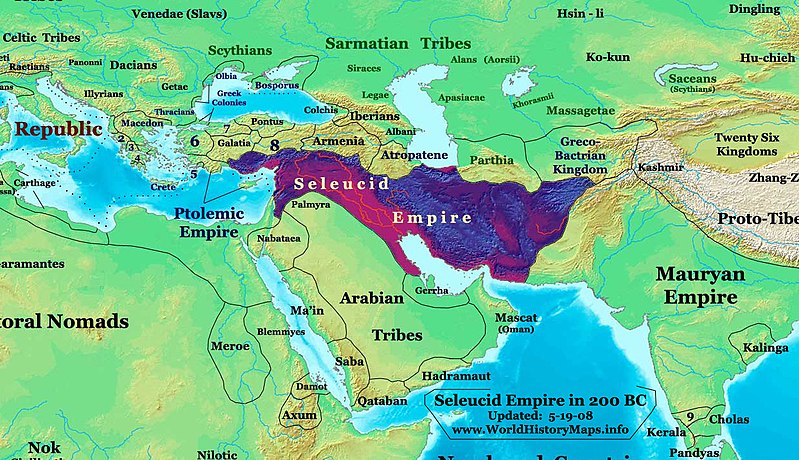

“The Seleucid Empire was a Greek state in West Asia that existed from 312–64 BCE:

- Founded: By Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator after the division of Alexander the Great’s Macedonian Empire

- Location: Stretched from Thrace in Europe to the border of India, and included Babylonia, Syria, and Anatolia

- Capital: Antioch in Syria and Seleucia in Mesopotamia (Iraq) Google ai

“Antiochus IV Epiphanes (born c. 215 bce—died 164, Tabae, Iran) was the Seleucid king of the Hellenistic Syrian kingdom who reigned from 175 to 164 bce. As a ruler, he was best known for his encouragement of Greek culture and institutions. His attempts to suppress Judaism brought on the Wars of the Maccabees.” Britannica

Grand Festival At Daphne

“When this same king (Antiochus Epiphanes) heard of the

games in Macedonia held by the Roman proconsul Aemilius Paulus, wishing to out do Paulus by the splendour of his liberality, he sent envoys to the several cities announcing games to be held by him at Daphne; and it became the rage in Greece to attend them. The public ceremonies began with a procession composed as follows: first came some men armed in the Roman fashion, with their coats made of chain armour, five thousand in the prime of life. Next came five thousand Mysians, who were followed by three thousand Cilicians armed like light infantry, and wearing gold crowns. Next to them came three thousand Thracians and five thousand Gauls. They were followed by twenty-thousand Macedonians, and five thousand armed with brass shields, and others with silver shields, who were followed by two hundred and forty pairs of gladiators. Behind these were a thousand Nisaean cavalry and three thousand native horsemen, most of whom had gold plumes and gold crowns, the rest having them of silver. Next to them came what are called “companion cavalry,” to the number of a thousand, closely followed by the corps of king’s “friends” of about the same number, who were again followed by a thousand picked men; next to whom came the Agema or guard, which was considered the flower of the cavalry, and numbered about a thousand. Next came the “cataphract” cavalry, both men and horses acquiring that name from the nature of their panoply; they numbered fifteen hundred. All the above men had purple surcoats, in many cases embroidered with gold and heraldic designs. And behind them came a hundred six-horsed, and forty four-horsed chariots; a chariot drawn by four elephants and another by two; and then thirty-six elephants in single file with all their furniture on.

“The rest of the procession was almost beyond description, but I must give a summary account of it. It consisted of eight hundred young men wearing gold crowns, about a thousand fine oxen, foreign delegates to the number of nearly three hundred, and eight hundred ivory tusks. The number of images of the gods it is impossible to tell completely: for representations of every god or demigod or hero accepted by mankind were carried there, some gilded and others adorned with gold-embroidered robes; and the myths, belonging to each, according to accepted tradition, were represented by the most costly symbols. Behind them were carried representations of Night and Day, Earth, Heaven, Morning and Noon. The best idea that I can give of the amount of gold and silver plate is this: One of the king’s friends, Dionysius his secretary, had a thousand boys in the procession carrying silver vessels, none of which weighed less than a thousand drachmae;1 and by their side walked six hundred young slaves of the king holding gold vessels. There were also two hundred women sprinkling unguents from gold boxes; and after them came eighty women sitting in litters with gold feet, and five hundred in litters with silver feet, all adorned with great costliness. These were the most remarkable features of the procession.”

1 A drachma may be taken as between a sixth and a seventh of an ounce.

“When the Roman Emperor Nero sat at banquet in his golden palace, a shower of flowers and perfumes fell upon him; but Heliogabalus turned these floral luxuries into veritable curses, for it was one of the pleasures of this inhuman being to smother his courtiers with flowers.

“Both Greeks and Romans caried the delicate refinements of the taste for flowers and perfumes to the greatest excess in their costly entertainments; and it is the opinion of Baccius that at their desserts the number of their flowers far exceeded that of their fruits. The odour of flowers was deemed potent to arouse the fainting appetite; and their presence was rightly thought to enhance the enjoyment of the guests at their banqueting boards:—

“In all places where festivals, games, or solemn ceremonials were held, and whenever public rejoicings and gaiety were deemed desirable, flowers were utilised with unsparing hands.

“In the triumphal processions of Rome the streets were strewed with flowers, and from the windows, roofs of houses, and scaffolds, the people cast showers of garlands and flowers upon the crowds below and upon the conquerors proudly marching in procession through the city. Macaulay says

In the processions of the Corybantes, the goddess Cybele, the protectress of cities, was pelted with white Roses. In the annual festivals of the Terminalia, the peasants were all crowned with garlands of flowers; and at the festival held by the gardeners in honour of Vertumnus on August 23rd, wreaths of budding flowers and the first-fruits of their gardens were offered by members of the craft.

“In the sacrifices of both Greeks and Romans, it was customary to place in the hands of victims some sort of floral decoration, and the presiding priests also appeared crowned with flowers.

“The place erected for offerings was called by the Romans ara, an altar. It was decorated with leaves and grass, adorned with flowers, and bound with woollen fillets: on the occasion of a “triumph” these altars smoked with perfumed incense.

Nymph of Flowers

Nymph with Flowers

Jules Lefebvre

“The Greeks had a Nymph of Flowers whom they called Chloris,

and the Romans the goddess Flora, who, among the Sabines and the Phoceans, had been worshipped long before the foundation of the Eternal City.

As early as the time of Romulus the Latins instituted a festival in honour of Flora, which was intended as a public expression of joy at the appearance of the welcome blossoms which were everywhere regarded as the harbingers of fruits. Five hundred and thirteen years after the foundation of Rome the Floralia, or annual floral games, were established; and after the sibyllic books had been consulted, it was finally ordained that the festival should be kept every 20th day of April, that is four days before the calends of May—the day on which, in Asia Minor, the festival of the flowers commences. In Italy, France, and Germany, the festival of the flowers, or the festival of spring, begins about the same date—i.e., towards the end of April—and terminates on the feast of St. John.

A-Maying

“The festival of the Floralia was introduced into Britain by the Romans; and for centuries all ranks of people went out a-Maying early on the first of the month. The juvenile part of both sexes, in the north, were wont to rise a little after midnight, and walk to some neighbouring wood, accompanied with music and the blowing of horns,

They also gathered branches from the trees, and adorned them with nosegays and crowns of flowers, returning with their booty homewards, about the rising of the sun, forthwith to decorate their doors and windows with the flowery spoil.

Maypole

“The after-part of the day, says an ancient chronicler, was “chiefly spent in dancing round a tall pole, which is called a May-pole; which, being placed in a convenient part of the village, stands there, as it were, consecrated to the goddess of flowers, without the least violation offered it in the whole circle of the year.”

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.