Before we talk about the story, “A Rose for Emily,” let’s talk about William Faulkner and his Yoknapatawpha County for a moment:

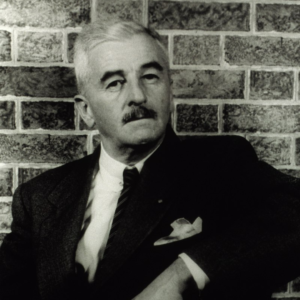

“William Faulkner…(born September 25, 1897, New Albany, Mississippi, U.S.—died July 6, 1962, Byhalia, Mississippi), [was an] American novelist and short-story writer who was awarded the 1949 Nobel Prize for Literature. As the eldest of the four sons of Murry Cuthbert and Maud Butler Falkner, William Faulkner (as he later spelled his name) was well aware of his family background and especially of his great-grandfather, Colonel William Clark Falkner, a colourful if violent figure who fought gallantly during the Civil War, built a local railway, and published a popular romantic novel called The White Rose of Memphis.” Britannica

Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” was published in 1930, but the time period of the story dates back to the 1800s–to a time not long after the Civil War. The lifestyle of white Southern planters was radically altered by the Civil War. Since slavery was abolished as a result of that war, the planters lost the laborers who had harvested their cotton, and they suffered financially. But many Southerners refused to acknowledge that their statuses had changed.

In Gone with the Wind, Scarlet O’Hara’s family had suffered downward mobility during the Civil War, but Scarlet refused to allow anyone to know how bad her financial situation was. In one scene, Scarlet’s gorgeous plantation had been destroyed, and Scarlet herself was starving. In a moment of desperation, she declared:

“I’m going to live through this and when it’s all over, I’ll never be hungry again. No, nor any of my folk. If I have to lie, steal, cheat or kill. As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again.”

And Scarlet O’Hara did survive. But in doing so, she became less than an admirable Southern Belle. In my opinion, the title “Gone with the Wind” alludes to the fact that by the end of the Civil War, the Southern Myth had begun its march toward beint “Gone with the Wind.” Faulkner’s books expose that myth and they reflect on the new South and its refusal to acknowledge that the days of the Southern Myth have ended.

Faulkner frequently focused on the hypocrisy that arose as many Southerners hid the fact that they were no longer a type of Southern Royalty.

Most of Faulkner’s books and stories take place in his fictional Yoknapatawpha County.

In “A Rose for Emily,” Miss Emily’s House is an important symbol. Like Scarlet O’Hara’s Tara, the Grierson’s home was not the house that it had been during better financial times.

Like so many things Deep South, there is a Colonel in “A Rose for Emily.”

Like Colonel Sanders himself, the Colonel in Faulkner’s writing is a symbol for a Deep South that cannot get over its loss of the Civil War. Invariably, the Colonels of the Southern Culture are reminiscent of the Colonels during the campaign of the Civil War, a war that is highly romanticized, like many other things in the South. To have been a Southern Colonel would have been comparable to the Knight in Shining Armour who carried the Queen’s flag into a noble battle. The Southern Colonel is part of the Southern Myth. Most people believe that Colonel Sartoris, in Faulkner’s writing, is based on the writer’s own grandfather Colonel William Falkner, who was indeed a Colonel in the Civil War. Faulkner added the “u” to the original spelling of Falkner.

The time of “A Rose for Emily” was set during the early 1900s, but several years before that time, Colonel Sartoris had hatched a plan to camouflage the fact that Emily’s father no longer had enough money to pay his taxes:

“Colonel Sartoris invented an involved tale to the effect that Miss Emily’s father had loaned money to the town, which the town, as a matter of business, preferred this way of repaying. Only a man of Colonel Sartoris’ generation and thought could have invented it, and only a woman could have believed it.

“When the next generation, with its more modern ideas, became mayors and aldermen, this arrangement created some little dissatisfaction. On the first of the year they mailed her a tax notice.”

In the above passage, Faulkner reveals that he is contrasting the Old South with the New South.

In the same way that her house had fallen into disrepair, Miss Emily’s personal appearance had slipped, too:

“They rose when she entered–a small, fat woman in black, with a thin gold chain descending to her waist and vanishing into her belt, leaning on an ebony cane with a tarnished gold head. Her skeleton was small and spare; perhaps that was why what would have been merely plumpness in another was obesity in her. She looked bloated, like a body long submerged in motionless water, and of that pallid hue. Her eyes, lost in the fatty ridges of her face, looked like two small pieces of coal pressed into a lump of dough as they moved from one face to another while the visitors stated their errand.”

“We’re Captive on the Carousel of Time” – Joni Mitchell

Faulkner alludes to the cyclical nature of time by saying that every year, a tax notice was sent to Miss Emily.

At least twice Faulkner mentioned the routine going and coming of the man who worked for Emily Grierson:

“Daily, monthly, yearly we watched the Negro grow grayer and more stooped, going in and out with the market basket. Each December we sent her a tax notice, which would be returned by the post office a week later, unclaimed.

Faulkner also made reference to the ticking away of time:

“… they could hear the invisible watch ticking at the end of the gold chain.”

All of these repeated behaviors become cycles–or as Joni Mitchell said, “The Circle Game.”

Shakespeare once observed that something was foul in Denmark:

“Something’s Rotten in the State of Denmark.” – Shakespeare

In Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” Something’s Rotten in Jefferson, Mississippi, too. [Jefferson, Mississippi is a town in Faulkner’s Fictional Yoknapatawpha County. It is primarily based on the real town of Oxford, MS]

At the time when Emily Grierson was alive, people would have used outhouses as their bathrooms. There is no way to flush an outhouse, and they smelled bad. Lime is a white, powdery substance, and it was sprinkled down into the holes of an outhouse to help camouflage the odors in outhouses, but the stench of an outhouse never goes away completely. The stench around Emily Grierson never went away either. In the story “A Rose for Emily,” it seems to be symbolic that the sneaking aldermen used lime to camouflage the odor that they associated with Miss Emily. It is as though Faulkner is suggesting that the Grierson family has become smelly, too. Certainly, the Grierson house had an odor, and Houses are often Symbols in Literature.

The lime was a way to camouflage the odor coming from the Grierson’s house. Camouflage is a type of hypocrisy–a type of hiding in plain sight. The odor about the Grierson’s house was a multifaceted thing. It was more than the mere stench of a rotting body. The Griersons themselves were rotting. No doubt, Emily Grierson is symbolic of the Southern Myth, which Faulkner believed had begun to rot.

The people in town “…believed that the Griersons held themselves a little too high for what they really were. None of the young men were quite good enough for Miss Emily and such.”

Like Rhett Butler in Gone with the Wind, Homer Barron, a Yankee, imposes himself upon the Southern town of Jefferson. Being a Yankee was especially offensive to pretentious Southerners, but Homer Barron was also little more than a day laborer. He had two strikes against him, and the people in Jefferson, Mississippi, thought that Homer Barron was not an appropriate suitor for Miss Emily. But Emily Grierson seems to have become romantically involved with Homer Barron, in spite of what the neighbors thought:

“Presently we began to see him and Miss Emily on Sunday afternoons driving in the yellow-wheeled buggy and the matched team of bays from the livery stable.

“At first we were glad that Miss Emily would have an interest, because the ladies all said,’ Of course a Grierson would not think seriously of a Northerner, a day laborer.’ But there were still others, older people, who said that even grief could not cause a real lady to forget noblesse oblige….”

“noblesse oblige

Hypocrisy and Appearances in “A Rose for Emily”

In the first paragraph of the story “A Rose for Emily,” Faulkner shines a light on the hypocrisy in Jefferson, Mississippi:

“WHEN Miss Emily Grierson died, our whole town went to her funeral: the men through a sort of respectful affection for a fallen monument, the women mostly out of curiosity to see the inside of her house….”

Appearances Are Very Important In Maintaining the Southern Myth

The neighbors did not approve of Miss Emily’s relationship with Homer Barron, but they would not confront her directly. “The men did not want to interfere, but at last the ladies forced the Baptist minister–Miss Emily’s people were Episcopal– to call upon her.” This is another example of hypocrisy. It is double hypocrisy. Emily Grierson’s religious leader was not sent to call on her. The townspeople of Jefferson, most of whom were no doubt Baptist, thought it better to send their own Baptist minister to call on Emily Grierson. When the Baptist preacher failed, his wife picked up the mission.

After a while, Homer Barron seems to have disappeared. Miss Emily’s appearance faltered soon thereafter.

“When we next saw Miss Emily, she had grown fat and her hair was turning gray. During the next few years it grew grayer and grayer until it attained an even pepper-and-salt iron-gray, when it ceased turning. Up to the day of her death at seventy-four it was still that vigorous iron-gray, like the hair of an active man.”

Why did Faulkner name this short story “A Rose for Emily?”

To be honest, I am not sure. Scholars all around the world debate what the title of Faulkner’s story means.

In my opinion, Faulkner allows us a glimpse of the title’s meaning in the following words:

“When the Negro opened the blinds of one window, they could see that the leather was cracked; and when they sat down, a faint dust rose sluggishly about their thighs, spinning with slow motes in the single sun-ray. On a tarnished gilt easel before the fireplace stood a crayon portrait of Miss Emily’s father.”

In my opinion, the Rose for Emily is a Dust Rose.

In the above passage, Faulkner is also alluding to the themes of Darkness versus Light in his story:

The windows in Emily Grierson’s home were covered by blinds. Typically, the blinds were shut, and Emily rarely looks outside. Because of those blinds, the house itself was dark and shadowy. But Emily’s ability to see out into the world was also obscured. By this, I am saying that Emily could not truly see, There is only a “….single sun-ray. On a tarnished gilt….”

“So the next night, after midnight, four men crossed Miss Emily’s lawn and slunk about the house like burglars ….”

In my opinion, Faulkner is saying that the people of Jefferson, Mississippi, lacked the light of understanding–they lacked enlightenment, and because of that, they could not truly see. They may have looked, but they did not see.

TWO times, Faulkner mentioned the “crayon portrait” of Emily Grierson’s father. Most portraits are painted in oil, but Emily’s father’s portrait was painted in crayon. In saying the word “crayon,” I believe that Faulkner was saying that the Grierson portrait was created with something like colored pencils. Certainly, the Grierson portrait was not oil. I believe that Faulkner is saying that the portrait itself was a kind of joke and that it was created as yet another way to try to keep up with the Joneses. It is another type of hypocrisy. The mentioning of the Grierson portrait made me think of the following poem by Emily Dickinson:

Portraits are to daily faces ca. 1860

Emily Dickinson

Portraits are to daily faces

As an Evening West,

To fine, pedantic sunshine—

In a satin Vest!

Very simply, Dickinson is saying that portraits are not the real thing. A portrait of a person is not the actual person. Worse still, it is like trying to dress the sunshine itself in a satin Vest.

In other words, the satin Vest is just too much. The sunshine was beautiful before the satin vest was wrapped around it–the satin vest is too much. It is gilding the lily.

The last thing that I want to discuss is whether or not Emily Grierson was a prisoner in her own house.

I lived in Mississippi most of my life, and when I first read “A Rose for Emily, “I imagined that there was an old iron fence around the Grierson house. Old Victorian houses enclosed within iron fences are so very common in Mississippi that they have become cliché.

Winnie Foster’s home in the movie Tuck Everlasting had that kind of fence around it, too,

In the book, Babbitt affirms that there is a fence around the Foster home. The man in the yellow suit pauses at Winnie’s gate. It is significant that the man in the yellow suit stands on the other side of the Fosters’ Fence. He is kept out of the Foster’s home.

When I ponder upon the possibility that a fence might have grown up around Emily Grierson’s home, too, I am reminded of the poem “A Fence” by Carl Sandburg,

A Fence

Carl Sandburg

Now the stone house on the lake front is finished and the

workmen are beginning the fence.

The palings are made of iron bars with steel points that

can stab the life out of any man who falls on them.

As a fence, it is a masterpiece, and will shut off the rabble

and all vagabonds and hungry men and all wandering

looking for a place to play.

Passing through the bars and over the steel points will go

nothing except Death and the Rain and Tomorrow.

I had to read “A Rose for Emily” 3 times to be sure that an iron fence was not mentioned as having been erected around the Grierson home. Although I saw no mention of a physical fence in the story, I feel sure that Faulkner has placed Emily Grierson in another type of fence–an emotional one,

Faulkner repeatedly says that the windows of Emily’s home are covered by slats or blinds, and the other women in Jefferson only looked at Miss Emily through the slats and jalousies that covered their own windows:

“This behind their hands; rustling of craned silk and satin behind jalousies closed upon the sun of Sunday afternoon as the thin, swift clop-clop-clop of the matched team passed: ‘Poor Emily.'”

Like the rails of a fence, the slats form a fence-like barrier at the windows, and other than through a quick glance outside her windows, Emily rarely went outside in the latter years of her life.

“WHEN Miss Emily Grierson died, our whole town went to her funeral: the men through a sort of respectful affection for a fallen monument, the women mostly out of curiosity to see the inside of her house, which no one save an old man-servant–a combined gardener and cook–had seen in at least ten years.”

“From that time on her front door remained closed, save for a period of six or seven years, when she was about forty, during which she gave lessons in china-painting.”

“When the Negro opened the blinds of one window, they could see that the leather was cracked; and when they sat down, a faint dust rose sluggishly about their thighs, spinning with slow motes in the single sun-ray. “

“After her father’s death she went out very little; after her sweetheart went away, people hardly saw her at all. A few of the ladies had the temerity to call, but were not received, and the only sign of life about the place was the Negro man–a young man then–going in and out with a market basket.”

“She had some kin in Alabama; but years ago her father had fallen out with them over the estate of old lady Wyatt, the crazy woman, and there was no communication between the two families. They had not even been represented at the funeral.”

” The front door closed upon the last one and remained closed for good. When the town got free postal delivery, Miss Emily alone refused to let them fasten the metal numbers above her door and attach a mailbox to it.”

“Now and then we would see her in one of the downstairs windows–she had evidently shut up the top floor of the house–like the carven torso of an idol in a niche, looking or not looking at us, we could never tell which. Thus she passed from generation to generation–dear, inescapable, impervious, tranquil, and perverse.”

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.