Lady Jane Wilde

Image Credit: Wikimedia

I research almost every day, and I write almost every day. On most days, I write about what I have discovered in my resarch, and the past two days, I have been researching Celtic Folklore. Several times, writers have mentioned the name Lady Wilde as a source for this bit of info about Celtic Mythology or that. For a while, I simply scratched my head and moved on–until I decided to pause and see who Lady Jane Wilde was. Realizing that Wikipedia can be a trap of misinformation, it is such an easy go-to for checking this or that out. I was stunned to discover that Lady Jane Wilde was Oscar Wilde’s Mother. How could I not have known that before?

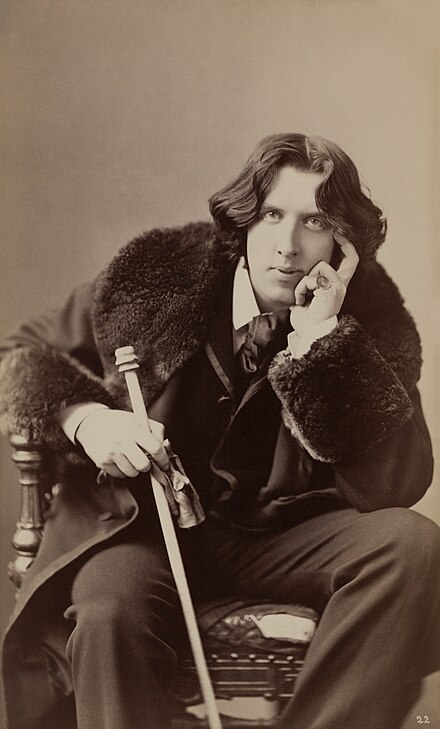

Oscar Wilde

Image Credit: Wikipedia

For years, Oscar Wilde has been one of my literary heroes–and I must admit that I also appreciated his spunk!

It was in 2015 that I first quoted the following treasure from Oscar Wilde:

“So with curious eyes and sick surmise

We watched him day by day,

And wondered if each one of us

Would end the self-same way,

For none can tell to what red Hell

His sightless soul may stray”. – Oscar Wilde

I included the above snippet of Wilde’s poem when I wrote my first version of the following post in 2015:

I have quoted other of Oscar Wilde’s words, but today, I’m writing about the fact that in spite of my history of daily research and my appreciation of Oscar Wilde, I never before connected him to Celtic Folklore–albeit through his mother. In the end, Lady Jane Wilde died penniless, but that is fodder for another post.

Kudos to the Power of Research — It Is How We Connect our Slices of Understanding!

My current interest in Lady Jane Wilde is that she collected numerous Celtic myths and has gifted the world with her understanding of the field through her book: Ancient Legends of Ireland.

Ancient Legends

Mystic Charms & Superstitions

of Ireland

WITH SKETCHES OF THE IRISH PAST

Published in 1919

Preface

“The Irish race were never much indebted to the written word. The learned class, the ollamhs, dwelt apart and kept their knowledge sacred. The people therefore lived entirely upon the traditions of their forefathers, blended with the new doctrines taught by Christianity; so that the popular belief became, in time, an amalgam of the pagan myths and the Christian legend, and these two elements remain indissolubly united to this day. The world, in fact, is a volume, a serial rather, going on for six thousand years, but of which the Irish peasant has scarcely yet turned the first page.

“The present work deals only with the mythology, or the fantastic creed of the Irish respecting the invisible world—strange and mystical superstitions, brought thousands of years ago from their Aryan home, but which still, even in the present time, affect all the modes of thinking and acting in the daily life of the people.

…

“The superstition, then, of the Irish peasant is the instinctive belief in the existence of certain unseen agencies that influence all human life; and with the highly sensitive organization of their race, it is not wonderful that the people live habitually under the shadow and dread of invisible powers which, whether working for good or evil, are awful and mysterious to the uncultured mind that sees only the strange results produced by certain forces, but knows nothing of approximate causes.

“Many of the Irish legends, superstitions, and ancient charms now collected were obtained chiefly from oral communications made by the peasantry themselves, either in Irish or in the Irish-English which preserves so much of the expressive idiom of the antique tongue.

“These narrations were taken down by competent persons skilled in both languages, and as far as possible in the very words of the narrator; so that much of the primitive simplicity of the style has been retained, while the legends have a peculiar and special value as coming direct from the national heart.

“In a few years such a collection would be impossible, for the old race is rapidly passing away to other lands, and in the vast working-world of America, with all the new influences of light and progress, the young generation, though still loving the land of their fathers, will scarcely find leisure to dream over the fairy-haunted hills and lakes and raths of ancient Ireland.

“I must disclaim, however, all desire to be considered a melancholy Laudatrix temporis acti. These studies of the Irish past are simply the expression of my love for the beautiful island that gave me my first inspiration, my quickest intellectual impulses, and the strongest and best sympathies with genius and country possible to a woman’s nature.

FRANCESCA SPERANZA WILD

[Lady Jane Wilde was called Speranza]

ANCIENT LEGENDS.

INTRODUCTION.

“The ancient legends of all nations of the world, on which from age to age the generations of man have been nurtured, bear so striking a resemblance to each other that we are led to believe there was once a period when the whole human family was of one creed and one language. But with increasing numbers came the necessity of dispersion; and that ceaseless migration was commenced of the tribes of the earth from the Eastern cradle of their race which has now continued for thousands of years with undiminished activity.

“From the beautiful Eden-land at the head of the Persian Gulf, where creeds and culture rose to life, the first migrations emanated, and were naturally directed along the line of the great rivers, by the Euphrates and the Tigris and southward by the Nile; and there the first mighty cities of the world were built, and the first mighty kingdoms of the East began to send out colonies to take possession of the unknown silent world around them. From Persia, Assyria, and Egypt, to Greece and the Isles of the Sea, went forth the wandering tribes, carrying with them, as signs of their origin, broken fragments of the primal creed, and broken idioms of the primal tongue—those early pages in the history of the human race, eternal and indestructible, which hundreds of centuries have not been able to obliterate from the mind of man.

“But as the early tribes diverged from the central parent stock, the creed and the language began to assume new forms, according as new habits of life and modes of thought were developed amongst the wandering people, by the influence of climate and the contemplation of new and striking natural phenomena in the lands where they found a resting-place or a home. Still, amongst all nations a basis remained of the primal creed and language, easily to be traced through all the mutations caused by circumstances in human thought, either by higher culture or by the debasement to which both language and symbols are subjected amongst rude and illiterate tribes.

“To reconstruct the primal creed and language of humanity[pg.2] from these scattered and broken fragments, is the task which is now exciting so keenly the energies of the ardent and learned ethnographers of Europe; as yet, indeed, with but small success as regards language, for not more, perhaps, than twenty words which the philologists consider may have belonged to the original tongue have been discovered; that is, certain objects or ideas are found represented in all languages by the same words, and therefore the philologist concludes that these words must have been associated with the ideas from the earliest dawn of language; and as the words express chiefly the relations of the human family to each other, they remained fixed in the minds of the wandering tribes, untouched and unchanged by all the diversities of their subsequent experience of life.

“…certain objects or ideas are found represented in all languages by the same words, and therefore the philologist concludes that these words must have been associated with the ideas from the earliest dawn of language; and as the words express chiefly the relations of the human family to each other, they remained fixed in the minds of the wandering tribes, untouched and unchanged by all the diversities of their subsequent experience of life. …

Persia Is the Source of Creed and Culture

“This source of all life, creed, and culture now on earth, there is no reason to doubt, will be found in Iran, or Persia as we call it, and in the ancient legends and language of the great Iranian people, the head and noblest type of the Aryan races. Endowed with splendid physical beauty, noble intellect, and a rich musical language, the Iranians had also a lofty sense of the relation between man and the spiritual world. They admitted no idols into their temples; their God was the One Supreme Creator and Upholder of all things, whose symbol was the sun and the pure, elemental fire. But as the world grew older and more wicked the pure primal doctrines were obscured by human fancies, the symbol came to be worshipped in place of the God, and the debased idolatries of Babylon, Assyria, and the Canaanite nations were the result. Egypt—grave, wise, learned, mournful Egypt—retained most of the primal truth; but truth was held by the priests as too precious for the crowd, and so they preserved it carefully for themselves and their own caste. They alone knew the ancient and cryptic meaning of the symbols; the people were allowed only to see the outward and visible sign.

Ancient Egypt Is the Source of Philosphy, Art, and Culture

“From Egypt, philosophy, culture, art,

Ancient Greece Is the Source of Religion

and religion came to Greece, but the Greeks moulded these splendid elements after their own fashion, and poured the radiance of beauty over the grave and gloomy mysticism of Egypt. …The Greek gods were divinely beautiful, and each divinity in turn was ready to help the mortal that invoked him. The dead in Hades mourned their fate because they could no longer enjoy the glorious beauty of life, but no hard and chilling dogmas doomed them there to the tortures of eternal punishment. Earth, air, the heavens and the sea, the storms and sunshine, the forests and flowers and the purple grapes with which they crowned a god, were all to the Greek poet-mind the manifestations of an all-pervading spiritual power and life. A sublime Pantheism was their creed, that sees gods in everything, yet with one Supreme God over all. Freedom, beauty, art, light, and joy, were the elements of the Greek religion, while the Eternal Wisdom, the Great Athené of the Parthenon, was the peculiar and selected divinity of their own half divine race.

The Teuton and Gothic Races

“Meanwhile other branches of the primal Iranian stock were spreading over the savage central forests of Europe, where they laid the foundation of the great Teuton and Gothic races, the destined world-rulers; but Nature to them was a gloomy and awful mother, and life seemed an endless warfare against the fierce and powerful elemental demons of frost and snow and darkness, by whom the beautiful Sun-god was slain, and who reigned triumphant in that fearful season when the earth was iron and the air was ice, and no beneficent God seemed near to help. Hideous idols imaged these unseen powers, who were propitiated by sanguinary rites; and the men and the god they fashioned were alike as fierce and cruel as the wild beasts of the forest, and the aspects of the savage nature around them.

The Celtic Race

“Still the waves of human life kept rolling westward until they surged over all the lands and islands of the Great Sea, and the wandering mariners, seeking new homes, passed through the Pillars of Hercules out into the Western Ocean, and coasting along by the shores of Spain and France, founded nations that still bear the impress of their Eastern origin, and are known in history as the Celtic race; while the customs, usages, and traditions which their forefathers had learnt in Egypt or Greece were carefully preserved by them, and transmitted as heirlooms to the colonies they founded. From Spain the early mariners easily reached the verdant island of the West in which we Irish are more particularly interested. And here in our beautiful Ireland the last wave of the great Iranian migration finally4 settled. Further progress was impossible—the unknown ocean seemed to them the limits of the world. And thus the wanderers of the primal race, with their fragments of the ancient creed and mythic poet-lore, and their peculiar dialect of the ancient tongue, formed, as it were, a sediment here which still retains its peculiar affinity with the parent land—though the changes and chances of three thousand years have swept over the people, the legends, and the language. It is, therefore, in Ireland, above all, that the nature and origin of the primitive races of Europe should be studied. Even the form of the Celtic head shows a decided conformity to that of the Greek races, while it differs essentially from the Saxon and Gothic types. This is one of the many proofs in support of the theory that the Celtic people in their westward course to the Atlantic travelled by the coasts of the Mediterranean, as all along that line the same cranial formation is found. Philologists also affirm that the Irish language is nearer to Sanskrit than any other of the living and spoken languages of Europe; while the legends and myths of Ireland can be readily traced to the far East, but have nothing in common with the fierce and weird superstitions of Northern mythology.

“This study of legendary lore, as a foundation for the history of humanity, is now recognized as such an important branch of ethnology that a journal entirely devoted to comparative mythology has been recently started in Paris, to which all nations are invited to contribute—Sclaves, Teutons, and Celts, Irish legends being considered specially important, as containing more of the primitive elements than those of other Western nations. All other countries have been repeatedly overwhelmed by alien tribes and peoples and races, but the Irish have remained unchanged, and in place of adopting readily the usages of invaders they have shown such remarkable powers of fascination that the invaders themselves became Hibernicis ipsis Hiberniores. The Danes held the east coast of Ireland for three hundred years, yet there is no trace of Thor or Odin or the Frost Giants, or of the Great World-serpent in Irish legend; but if we go back in the history of the world to the beginning of things, when the Iranian people were the only teachers of humanity, we come upon the true ancient source of Irish legend, and find that the original materials have been but very slightly altered, while amongst other nations the ground-work has been overlaid with a dense palimpsest of their own devising, suggested by their peculiar local surroundings.

Sacred Tree

“Amongst the earliest religious symbols of the world are the Tree, the Woman, and the Serpent—memories, no doubt, of the legend of Paradise; and the reverence for certain sacred trees has prevailed in Persia from the most ancient times, and become diffused among all the Iranian nations. It was the custom in Iran to hang costly garments on the branches as votive offerings; and5 it is recorded that Xerxes before going to battle invoked victory by the Sacred Tree, and hung jewels and rich robes on the boughs. And the poet Saadi narrates an anecdote concerning trees which has the true Oriental touch of mournful suggestion:—He was once, he says, the guest of a very rich old man who had a son remarkable for his beauty. One night the old man said to him, “During my whole life I never had but this son. Near this place is a Sacred Tree to which men resort to offer up their petitions. Many nights at the foot of this tree I besought God until He bestowed on me this son.” Not long after Saadi overheard this young man say in a low voice to his friend, “How happy should I be to know where that Sacred Tree grows, in order that I might implore God for the death of my father.”

“The poorer class in Persia, not being able to make offerings of costly garments, are in the habit of tying bits of coloured stuffs on the boughs, and these rags are considered to have a special virtue in curing diseases. The trees are often near a well or by a saint’s grave, and are then looked upon as peculiarly sacred.

“This account might have been written for Ireland, for the belief and the ceremonial are precisely similar, and are still found existing to this day both in Iran and in Erin. But all trees were not held sacred—only those that bore no eatable fruit that could nourish men; a lingering memory of the tree of evil fruit may have caused this prejudice, while the Tree of Life was eagerly sought for, with its promised gift of immortality. In Persia the plane-tree was specially reverenced; in Egypt, the palm; in Greece, the wild olive; and the oak amongst the Celtic nations. Sometimes small tapers were lit amongst the branches, to simulate by fire the presence of divinity. It is worthy of note, while on the subject of Irish and Iranian affinities, that the old Persian word for tree is dar, and the Irish call their sacred tree, the oak, darragh.1

The Persians or Iranians Believed in Supernatural Fairy-Like Creatures

The belief in a race of supernatural beings, midway between man and the Supreme God, beautiful and beneficent, a race that had never known the weight of human life, was also part of the creed of the Iranian people. They called them Peris, or Feroüers (fairies); and they have some pretty legends concerning the beautiful Dukhtari Shah Periân, the “Daughter of the King of the Fairies,” for a sight of whose beauty men pine away in vain desire, but if it is granted to them once to behold her, they die. Every nation believes in the existence of these mysterious spirits, with mystic and powerful influence over human life and actions, but each nation represents them differently, according to national habits and national surroundings.

Russia

Thus, the Russians believe in the phantom [pg. 6] of the Ukraine, a beautiful young girl robed in white, who meets the wanderer on the lonely snow steppes, and lulls him by her kisses into that fatal sleep from which he never more awakens.

Scandinavians – Thor – Midsummer – Baal Fires – Christmas Trees

The legends of the Scandinavians, also, are all set in the framework of their own experiences; the rending and crash of the ice is the stroke of the god Thor’s hammer; the rime is the beard of the Frost Giant; and when Balder, their Sun-god, is beginning to die at Midsummer, they kindle pine-branches to light him on his downward path to hell; and when he is returning to the upper world, after the winter solstice, they burn the Yule-log, and hang lights on the fir-trees to illuminate his upward path. These traditions are a remnant of the ancient sun worship, but the peasants who kindle the Baal fires at Midsummer, and the upper classes who light up the brilliant Christmas-tree, have forgotten the origin of the custom, though the world-old symbol and usage is preserved.

Ireland – The Sidhe or Fairies of Ireland

The Sidhe, or Fairies, of Ireland, still preserve all the gentle attributes of their ancient Persian race, for in the soft and equable climate of Erin there were no terrible manifestations of nature to be symbolized by new images; and the genial, laughter-loving elves were in themselves the best and truest expression of Irish nature that could have been invented. The fairies loved music and dancing and frolic; and, above all things, to be let alone, and not to be interfered with as regarded their peculiar fairy habits, customs, and pastimes. They had also, like the Irish, a fine sense of the right and just, and a warm love for the liberal hand and kindly word. All the solitudes of the island were peopled by these bright, happy, beautiful beings, and to the Irish nature, with its need of the spiritual, its love of the vague, mystic, dreamy, and supernatural, there was something irresistibly fascinating in the belief that gentle spirits were around, filled with sympathy for the mortal who suffered wrong or needed help. But the fairies were sometimes wilful and capricious as children, and took dire revenge if any one built over their fairy circles, or looked at them when combing their long yellow hair in the sunshine, or dancing in the woods, or floating on the lakes. Death was the penalty to all who approached too near, or pried too curiously into the mysteries of nature.

To the Irish peasant earth and air were filled with these mysterious beings, half-loved, half-feared by them; and therefore they were propitiated by flattery, and called “the good people,” as the Greeks call the dread goddesses “the Eumenides.” Their voices were heard in the mountain echo, and their forms seen in the purple and golden mountain mist; they whispered amidst the perfumed hawthorn branches; the rush of the autumn leaves was the scamper of little elves—red, yellow, and brown—wind-delven, and dancing in their glee; and the bending of the waving [pg. 7] barley was caused by the flight of the Elf King and his Court across the fields. They danced with soundless feet, and their step was so light that the drops of dew they danced on only trembled, but did not break. The fairy music was low and sweet, “blinding sweet,” like that of the great god Pan by the river; they lived only on the nectar in the cups of the flowers, though in their fairy palaces sumptuous banquets were offered to the mortals they carried off—but woe to the mortal who tasted of fairy food; to eat was fatal.

*Jacki Note – This is like Persophone who mistakenly tasted the pomegranate seeds in Hades.

The Horae and Other Ancient Greek Deities that Celebrate the Seasons

“All the evil in the world has come by eating; if Eve had only resisted that apple our race might still be in Paradise. The Sidhe look with envy on the beautiful young human children, and steal them when they can;

and the children of a Sidhe and a mortal mother are reputed to grow up strong and powerful, but with evil and dangerous natures. There is also a belief that every seven years the fairies are obliged to deliver up a victim to the Evil One, and to save their own people they try to abduct some beautiful young mortal girl, and her they hand over to the Prince of Darkness.

Poets, Children, & the Irish Preserve the Sense of Myth

*Jacki Note – The Romantic Poets believed that the Child was a Link to the Infinite:

Spirituality, Aesthetics, and Nature: Romantic Writers – William Blake on the Imagination as Ideal

Dogmatic religion and science have long since killed the mythopoetic faculty in cultured Europe. It only exists now, naturally and instinctively, in children, poets, and the childlike races, like the Irish—simple, joyous, reverent, and unlettered, and who have remained unchanged for centuries, walled round by their language from the rest of Europe, through which separating veil science, culture, and the cold mockery of the sceptic have never yet penetrated.

The Irish Peasants Combined Christianity with their Fairy Faith

Christianity was readily accepted by the Irish. The pathetic tale of the beautiful young Virgin-Mother and the Child-God, for central objects, touched all the deepest chords of feeling in the tender, loving, and sympathetic Irish heart. The legends of ancient times were not overthrown by it, however, but taken up and incorporated with the new Christian faith. The holy wells and the sacred trees remained, and were even made holier by association with a saint’s name. And to this day the old mythology holds its ground with a force and vitality untouched by any symptoms of weakness or decay. The Greeks, who are of the same original race as our people, rose through the influence of the highest culture to the fulness and perfectness of eternal youth; but the Irish, without culture, are eternal children, with all the childlike instincts of superstition still strong in them, and capable of believing all things, because to doubt requires knowledge. They never, like the Greeks, attained to the conception of a race of beings nobler than themselves—men stronger and more gifted, with the immortal fire of a god in their veins; women divinely beautiful, or divinely inspired; but, also, the Irish never defaced the image of God in their hearts by infidelity or irreligion. One of the most beautiful and sublimely touching records in all[pg. 8]human history is that of the unswerving devotion of the Irish people to their ancient faith, through persecutions and penal enactments more insulting and degrading than were ever inflicted in any other land by one Christian sect upon another.

Skepticism Is Alien to Irish Temperament

With this peculiarly reverential nature it would be impossible to make the Irish a nation of sceptics, even if a whole legion of German Rationalists came amongst them to preach a crusade against all belief in the spiritual and the unseen. And the old traditions of their race have likewise taken firm hold in their hearts, because they are an artistic people, and require objects for their adoration and love, not mere abstractions to be accepted by their reason. And they are also a nation of poets; the presence of God is ever near them, and the saints and angels, and the shadowy beings of earth and air are perpetually drawing their minds, through mingled love and fear, to the infinite and invisible world. Probably not one tradition or custom that had its origin in a religious belief has been lost in Ireland during the long course of ages since the first people from Eastern lands arrived and settled on our shores. The Baal fires are still lit at Midsummer, though no longer in honour of the sun, but of St. John; and the peasants still make their cattle pass between two fires—not, indeed, as of old, in the name of Moloch, but of some patron saint. That all Irish legends point to the East for their origin, not to the North, is certain; to a warm land, not one of icebergs, and thunder crashes of the rending of ice-bound rivers, but to a region where the shadow of trees, and a cool draught from the sparkling well were life-giving blessings.

Well Worship

Well-worship could not have originated in a humid country like Ireland, where wells can be found at every step, and sky and land are ever heavy and saturated with moisture. It must have come from an Eastern people, wanderers in a dry and thirsty land, where the discovery of a well seemed like the interposition of an angel in man’s behalf.

Snakes and St. Patrick

We are told also by the ancient chroniclers that serpent-worship once prevailed in Ireland, and that St. Patrick hewed down the serpent idol Crom-Cruadh (the great worm) and cast it into the Boyne (from whence arose the legend that St. Patrick banished all venomous things from the island). Now as the Irish never could have seen a serpent, none existing in Ireland, this worship must have come from the far East, where this beautiful and deadly creature is looked upon as the symbol of the Evil One, and worshipped and propitiated by votive offerings, as all evil things were in the early world, in the hope of turning away their evil hatred from man, and to induce them to show mercy and pity; just as the Egyptians propitiated the sacred crocodile by subtle flatteries and hung costly jewels in its ears. The Irish, indeed, do not seem to have originated any peculiar or national cultus. Their funeral ceremonies recall those of Egypt and Greece and9 other ancient Eastern climes, from whence they brought their customs of the Wake, the death chant, the mourning women, and the funeral games. In Sparta, on the death of a king or great chief, they had a wake and “keen” not common to the rest of Greece, but which they said they learned from the Phœnicians; and this peculiar usage bears a striking resemblance to the Irish practice. All the virtues of the dead were recited, and the Greek “Eleleu,” the same cry as the “Ul-lu-lu” of the Irish, was keened over the corpse by the chorus of hired mourning women. The custom of selecting women in place of men for the chorus of lamentation prevailed throughout all the ancient world, as if an open display of grief was thought beneath the dignity of man. It was Cassandra gave the keynote for the wail over Hector, and Helen took the lead in reciting praises to his honour. The death chants in Egypt, Arabia, and Abyssinia all bear a marked resemblance to the Irish; indeed the mourning cry is the same in all, and the Egyptian lamentation “Hi-loo-loo! Hi-loo-loo!” cried over the dead, was probably the original form of the Irish wail.

The Greeks always endeavoured to lessen the terrors of death, and for this reason they established funeral games, and the funeral ceremonies took the form of a festival, where they ate and drank and poured libations of wine in honour of the dead. The Irish had also their funeral games and peculiar dances, when they threw off their upper garments, and holding hands in a circle, moved in a slow measure round a woman crouched in the centre, with her hands covering her face. Another singular part of the ceremony was the entrance of a woman wearing a cow’s head and horns, as Io appears upon the scene in the Prometheus of Æschylus. This woman was probably meant to represent the horned or crescented moon, the antique Diana, the Goddess of Death. The custom of throwing off the garments no doubt originally signified the casting off the garment of the flesh. We brought nothing into this world, and it is certain we carry nothing out. The soul must stand unveiled before God.

In the islands off the West Coast of Ireland, where the most ancient superstitions still exist, they have a strange custom. No funeral wail is allowed to be raised until three hours have elapsed from the moment of death, because, they say, the sound of the cries would hinder the soul from speaking to God when it stands before Him, and waken up the two great dogs that are watching for the souls of the dead in order that they may devour them—and the Lord of Heaven Himself cannot hinder them if once they waken. This tradition of watching by the dead in silence, while the soul stands before God, is a fine and solemn superstition, which must have had its origin amongst a people of intense faith in the invisible world, and is probably of great antiquity. …

THE HORNED WOMEN.

A rich woman sat up late one night carding and preparing wool, while all the family and servants were asleep. Suddenly a knock was given at the door, and a voice called—“Open! open!”

“Who is there?” said the woman of the house.

11

“I am the Witch of the One Horn,” was answered.

The mistress, supposing that one of her neighbours had called and required assistance, opened the door, and a woman entered, having in her hand a pair of wool carders, and bearing a horn on her forehead, as if growing there. She sat down by the fire in silence, and began to card the wool with violent haste. Suddenly she paused and said aloud: “Where are the women? They delay too long.”

Then a second knock came to the door, and a voice called as before—“Open! open!”

The mistress felt herself constrained to rise and open to the call, and immediately a second witch entered, having two horns on her forehead, and in her hand a wheel for spinning the wool.

“Give me place,” she said; “I am the Witch of the Two Horns,” and she began to spin as quick as lightning.

And so the knocks went on, and the call was heard, and the witches entered, until at last twelve women sat round the fire—the first with one horn, the last with twelve horns. And they carded the thread, and turned their spinning wheels, and wound and wove, all singing together an ancient rhyme, but no word did they speak to the mistress of the house. Strange to hear, and frightful to look upon were these twelve women, with their horns and their wheels; and the mistress felt near to death, and she tried to rise that she might call for help, but she could not move, nor could she utter a word or a cry, for the spell of the witches was upon her.

Then one of them called to her in Irish and said—

“Rise, woman, and make us a cake.”

Then the mistress searched for a vessel to bring water from the well that she might mix the meal and make the cake, but she could find none. And they said to her—

“Take a sieve and bring water in it.”

And she took the sieve and went to the well; but the water poured from it, and she could fetch none for the cake, and she sat down by the well and wept. Then a voice came by her and said—

“Take yellow clay and moss and bind them together and plaster the sieve so that it will hold.”

This she did, and the sieve held the water for the cake. And the voice said again—

“Return, and when thou comest to the north angle of the house, cry aloud three times and say, ‘The mountain of the Fenian women and the sky over it is all on fire.’”

And she did so.

When the witches inside heard the call, a great and terrible cry broke from their lips and they rushed forth with wild lamentations and shrieks, and fled away to Slieve-namon, where was their chief abode. But the Spirit of the Well bade the mistress of the [pg. 12] house to enter and prepare her home against the enchantments of the witches if they returned again.

And first, to break their spells, she sprinkled the water in which she had washed her child’s feet (the feet-water) outside the door on the threshold; secondly, she took the cake which the witches had made in her absence, of meal mixed with the blood drawn from the sleeping family. And she broke the cake in bits, and placed a bit in the mouth of each sleeper, and they were restored; and she took the cloth they had woven and placed it half in and half out of the chest with the padlock; and lastly, she secured the door with a great cross-beam fastened in the jambs, so that they could not enter. And having done these things she waited.

Not long were the witches in coming back, and they raged and called for vengeance.

“Open! Open!” they screamed. “Open, feet-water!”

“I cannot,” said the feet-water, “I am scattered on the ground and my path is down to the Lough.”

“Open, open, wood and tree and beam!” they cried to the door.

“I cannot,” said the door; “for the beam is fixed in the jambs and I have no power to move.”

“Open, open, cake that we have made and mingled with blood,” they cried again.

“I cannot,” said the cake, “for I am broken and bruised, and my blood is on the lips of the sleeping children.”

Then the witches rushed through the air with great cries, and fled back to Slieve-namon, uttering strange curses on the Spirit of the Well, who had wished their ruin; but the woman and the house were left in peace, and a mantle dropped by one of the witches in her flight was kept hung up by the mistress as a sign of the night’s awful contest; and this mantle was in possession of the same family from generation to generation for five hundred years after.

THE LEGEND OF BALLYTOWTAS CASTLE.

The next tale I shall select is composed in a lighter and more modern spirit. All the usual elements of a fairy tale are to be found in it, but the story is new to the nursery folk, and, if well illustrated, would make a pleasant and novel addition to the rather worn-out legends on which the children of many generations have been hitherto subsisting.

In old times there lived where Ballytowtas Castle now stands a poor man named Towtas. It was in the time when manna fell to the earth with the dew of evening, and Towtas lived by gathering [13 ]the manna, and thus supported himself, for he was a poor man, and had nothing else.

One day a pedlar came by that way with a fair young daughter.

“Give us a night’s lodging,” he said to Towtas, “for we are weary.”

And Towtas did so.

Next morning, when they were going away, his heart longed for the young girl, and he said to the pedlar, “Give me your daughter for my wife.”

“How will you support her?” asked the pedlar.

“Better than you can,” answered Towtas, “for she can never want.”

Then he told him all about the manna; how he went out every morning when it was lying on the ground with the dew, and gathered it, as his father and forefathers had done before him, and lived on it all their lives, so that he had never known want nor any of his people.

Then the girl showed she would like to stay with the young man, and the pedlar consented, and they were married, Towtas and the fair young maiden; and the pedlar left them and went his way. So years went on, and they were very happy and never wanted; and they had one son, a bright, handsome youth, and as clever as he was comely.

But in due time old Towtas died, and after her husband was buried, the woman went out to gather the manna as she had seen him do, when the dew lay on the ground; but she soon grew tired and said to herself, “Why should I do this thing every day? I’ll just gather now enough to do the week and then I can have rest.”

So she gathered up great heaps of it greedily, and went her way into the house. But the sin of greediness lay on her evermore; and not a bit of manna fell with the dew that evening, nor ever again. And she was poor, and faint with hunger, and had to go out and work in the fields to earn the morsel that kept her and her son alive; and she begged pence from the people as they went into chapel, and this paid for her son’s schooling; so he went on with his learning, and no one in the county was like him for beauty and knowledge.

One day he heard the people talking of a great lord that lived up in Dublin, who had a daughter so handsome that her like was never seen; and all the fine young gentlemen were dying about her, but she would take none of them. And he came home to his mother and said, “I shall go see this great lord’s daughter. Maybe the luck will be mine above all the fine young gentlemen that love her.”

“Go along, poor fool,” said the mother,14 “how can the poor stand before the rich?”

But he persisted. “If I die on the road,” he said, “I’ll try it.”

“Wait, then,” she answered, “till Sunday, and whatever I get I’ll give you half of it.” So she gave him half of the pence she gathered at the chapel door, and bid him go in the name of God.

He hadn’t gone far when he met a poor man who asked him for a trifle for God’s sake. So he gave him something out of his mother’s money and went on. Again, another met him, and begged for a trifle to buy food, for the sake of God, and he gave him something also, and then went on.

“Give me a trifle for God’s sake,” cried a voice, and he saw a third poor man before him.

“I have nothing left,” said Towtas, “but a few pence; if I give them, I shall have nothing for food and must die of hunger. But come with me, and whatever I can buy for this I shall share with you.” And as they were going on to the inn he told all his story to the beggar man, and how he wanted to go to Dublin, but had now no money. So they came to the inn, and he called for a loaf and a drink of milk. “Cut the loaf,” he said to the beggar. “You are the oldest.”

“I won’t,” said the other, for he was ashamed, but Towtas made him.

*Jacki Note – I am reminded of the Manna from Heaven in the Bible and the Scriptur John 6:35 New International Version

And so the beggar cut the loaf, but though they ate, it never grew smaller, and though they drank as they liked of the milk, it never grew less. Then Towtas rose up to pay, but when the landlady came and looked, “How is this?” she said. “You have eaten nothing. I’ll not take your money, poor boy,” but he made her take some; and they left the place, and went on their way together.

A Ring Legend — Which is a Precursor to Tolkien and the Hobbit

“Now,” said the beggar man, “you have been three times good to me to-day, for thrice I have met you, and you gave me help for the sake of God each time. See, now, I can help also,” and he reached a gold ring to the handsome youth. “Wherever you place that ring, and wish for it, gold will come—bright gold, so that you can never want while you have it.”

Then Towtas put the ring first in one pocket and then in another, until all his pockets were so heavy with gold that he could scarcely walk; but when he turned to thank the friendly beggar man, he had disappeared.

So, wondering to himself at all his adventures, he went on, until he came at last in sight of the lord’s palace, which was beautiful to see; but he would not enter in until he went and bought fine clothes, and made himself as grand as any prince; and then he went boldly up, and they invited him in, for they said, “Surely he is a king’s son.” And when dinner-hour came the lord’s daughter linked her arm with Towtas, and smiled on him. And he drank of the rich wine, and was mad with love; but at15 last the wine overcame him, and the servants had to carry him to his bed; and in going into his room he dropped the ring from his finger, but knew it not.

Now, in the morning, the lord’s daughter came by, and cast her eyes upon the door of his chamber, and there close by it was the ring she had seen him wear.

“Ah,” she said, “I’ll tease him now about his ring.” And she put it in her box, and wished that she were as rich as a king’s daughter, that so the king’s son might marry her; and, behold, the box filled up with gold, so that she could not shut it; and she put it from her into another box, and that filled also; and then she was frightened at the ring, and put it at last in her pocket as the safest place.

But when Towtas awoke and missed the ring, his heart was grieved.

“Now, indeed,” he said, “my luck is gone.”

And he inquired of all the servants, and then of the lord’s daughter, and she laughed, by which he knew she had it; but no coaxing would get it from her, so when all was useless he went away, and set out again to reach his old home.

And he was very mournful and threw himself down on the ferns near an old fort, waiting till night came on, for he feared to go home in the daylight lest the people should laugh at him for his folly. And about dusk three cats came out of the fort talking to each other.

“How long our cook is away,” said one.

“What can have happened to him?” said another.

And as they were grumbling a fourth cat came up.

“What delayed you?” they all asked angrily.

Then he told his story—how he had met Towtas and given him the ring. “And I just went,” he said, “to the lord’s palace to see how the young man behaved; and I was leaping over the dinner-table when the lord’s knife struck my tail and three drops of blood fell upon his plate, but he never saw it and swallowed them with his meat. So now he has three kittens inside him and is dying of agony, and can never be cured until he drinks three draughts of the water of the well of Ballytowtas.”

A Well Story

So when young Towtas heard the cats talk he sprang up and went and told his mother to give him three bottles full of the water of the Towtas well, and he would go to the lord disguised as a doctor and cure him.

The Healing Power of Water

Reminds me of Baptism Littany

So off he went to Dublin. And all the doctors in Ireland were round the lord, but none of them could tell what ailed him, or how to cure him. Then Towtas came in and said, “I will cure him.” So they gave him entertainment and lodging, and when he was refreshed he gave of the well water three draughts to his lordship, when out jumped the three kittens. And there was [pg. 16] great rejoicing, and they treated Towtas like a prince. But all the same he could not get the ring from the lord’s daughter, so he set off home again quite disheartened, and thought to himself, “If I could only meet the man again that gave me the ring who knows what luck I might have?” And he sat down to rest in a wood, and saw there not far off three boys fighting under an oak-tree.

“Shame on ye to fight so,” he said to them. “What is the fight about?”

Goblet Story

Then they told him. “Our father,” they said, “before he died, buried under this oak-tree a ring by which you can be in any place in two minutes if you only wish it; a goblet that is always full when standing, and empty only when on its side; and a harp that plays any tune of itself that you name or wish for.”

“I want to divide the things,” said the youngest boy, “and let us all go and seek our fortunes as we can.”

“But I have a right to the whole,” said the eldest.

And they went on fighting, till at length Towtas said—

“I’ll tell you how to settle the matter. All of you be here to-morrow, and I’ll think over the matter to-night, and I engage you will have nothing more to quarrel about when you come in the morning.”

So the boys promised to keep good friends till they met in the morning, and went away.

Harp Story

When Towtas saw them clear off, he dug up the ring, the goblet, and the harp, and now said he, “I’m all right, and they won’t have anything to fight about in the morning.”

Off he set back again to the lord’s castle with the ring, the goblet, and the harp; but he soon bethought himself of the powers of the ring, and in two minutes he was in the great hall where all the lords and ladies were just sitting down to dinner; and the harp played the sweetest music, and they all listened in delight; and he drank out of the goblet which was never empty, and then, when his head began to grow a little light, “It is enough,” he said; and putting his arm round the waist of the lord’s daughter, he took his harp and goblet in the other hand, and murmuring—“I wish we were at the old fort by the side of the wood”—in two minutes they were both at the desired spot. But his head was heavy with the wine, and he laid down the harp beside him and fell asleep. And when she saw him asleep she took the ring off his finger, and the harp and the goblet from the ground and was back home in her father’s castle before two minutes had passed by.

When Towtas awoke and found his prize gone, and all his treasures beside, he was like one mad; and roamed about the country till he came by an orchard, where he saw a tree covered with [17] bright, rosy apples. Being hungry and thirsty, he plucked one and ate it, but no sooner had he done so than horns began to sprout from his forehead, and grew larger and longer till he knew he looked like a goat, and all he could do, they would not come off. Now, indeed, he was driven out of his mind, and thought how all the neighbours would laugh at him; and as he raged and roared with shame, he spied another tree with apples, still brighter, of ruddy gold.

“If I were to have fifty pairs of horns I must have one of those,” he said; and seizing one, he had no sooner tasted it than the horns fell off, and he felt that he was looking stronger and handsomer than ever.

“Now, I have her at last,” he exclaimed. “I’ll put horns on them all, and will never take them off until they give her to me as my bride before the whole Court.”

Without further delay he set off to the lord’s palace, carrying with him as many of the apples as he could bring off the two trees. And when they saw the beauty of the fruit they longed for it; and he gave to them all, so that at last there was not a head to be seen without horns in the whole dining-hall. Then they cried out and prayed to have the horns taken off, but Towtas said—

“No; there they shall be till I have the lord’s daughter given to me for my bride, and my two rings, my goblet, and my harp all restored to me.”

And this was done before the face of all the lords and ladies; and his treasures were restored to him; and the lord placed his daughter’s hand in the hand of Towtas, saying—

“Take her; she is your wife; only free me from the horns.”

Golden Apple

Then Towtas brought forth the golden apples; and they all ate, and the horns fell off; and he took his bride and his treasures, and carried them off home, where he built the Castle of Ballytowtas, in the place where stood his father’s hut, and enclosed the well within the walls. And when he had filled his treasure-room with gold, so that no man could count his riches, he buried his fairy treasures deep in the ground, where no man knew, and no man has ever yet been able to find them until this day.

A WOLF STORY.

Transformation into wolves is a favourite subject of Irish legend, and many a wild tale is told by the peasants round the turf fire in the winter nights of strange adventures with wolves. Stories that had come down to them from their forefathers in the old times long ago; for there are no wolves existing now in Ireland.

18

A young farmer, named Connor, once missed two fine cows from his herd, and no tale or tidings could be heard of them anywhere. So he thought he would set out on a search throughout the country; and he took a stout blackthorn stick in his hand, and went his way. All day he travelled miles and miles, but never a sign of the cattle. And the evening began to grow very dark, and he was wearied and hungry, and no place near to rest in; for he was in the midst of a bleak, desolate heath, with never a habitation at all in sight, except a long, low, rude shieling, like the den of a robber or a wild beast. But a gleam of light came from a chink between the boards, and Connor took heart and went up and knocked at the door. It was opened at once by a tall, thin, grey-haired old man, with keen, dark eyes.

“Come in,” he said, “you are welcome. We have been waiting for you. This is my wife,” and he brought him over to the hearth, where was seated an old, thin, grey woman, with long, sharp teeth and terrible glittering eyes.

“You are welcome,” she said. “We have been waiting for you—it is time for supper. Sit down and eat with us.”

Now Connor was a brave fellow, but he was a little dazed at first at the sight of this strange creature. However, as he had his stout stick with him, he thought he could make a fight for his life any way, and, meantime, he would rest and eat, for he was both hungry and weary, and it was now black night, and he would never find his way home even if he tried. So he sat down by the hearth, while the old grey woman stirred the pot on the fire. But Connor felt that she was watching him all the time with her keen, sharp eyes.

Then a knock came to the door. And the old man rose up and opened it. When in walked a slender, young black wolf, who immediately went straight across the floor to an inner room, from which in a few moments came forth a dark, slender, handsome youth, who took his place at the table and looked hard at Connor with his glittering eyes.

“You are welcome,” he said, “we have waited for you.”

Before Connor could answer another knock was heard, and in came a second wolf, who passed on to the inner room like the first, and soon after, another dark, handsome youth came out and sat down to supper with them, glaring at Connor with his keen eyes, but said no word.

“These are our sons,” said the old man, “tell them what you want, and what brought you here amongst us, for we live alone and don’t care to have spies and strangers coming to our place.”

Then Connor told his story, how he had lost his two fine cows, and had searched all day and found no trace of them; and he knew nothing of the place he was in, nor of the kindly gentleman who asked him to supper; but if they just told him where to find19 his cows he would thank them, and make the best of his way home at once.

Then they all laughed and looked at each other, and the old hag looked more frightful than ever when she showed her long, sharp teeth.

On this, Connor grew angry, for he was hot tempered; and he grasped his blackthorn stick firmly in his hand and stood up, and bade them open the door for him; for he would go his way, since they would give no heed and only mocked him.

Then the eldest of the young men stood up. “Wait,” he said, “we are fierce and evil, but we never forget a kindness. Do you remember, one day down in the glen you found a poor little wolf in great agony and like to die, because a sharp thorn had pierced his side? And you gently extracted the thorn and gave him a drink, and went your way leaving him in peace and rest?”

“Aye, well do I remember it,” said Connor, “and how the poor little beast licked my hand in gratitude.”

“Well,” said the young man, “I am that wolf, and I shall help you if I can, but stay with us to-night and have no fear.”

So they sat down again to supper and feasted merrily, and then all fell fast asleep, and Connor knew nothing more till he awoke in the morning and found himself by a large hay-rick in his own field.

“Now surely,” thought he, “the adventure of last night was not all a dream, and I shall certainly find my cows when I go home; for that excellent, good young wolf promised his help, and I feel certain he would not deceive me.”

But when he arrived home and looked over the yard and the stable and the field, there was no sign nor sight of the cows. So he grew very sad and dispirited. But just then he espied in the field close by three of the most beautiful strange cows he had ever set eyes on. “These must have strayed in,” he said, “from some neighbour’s ground;” and he took his big stick to drive them out of the gate off the field. But when he reached the gate, there stood a young black wolf watching; and when the cows tried to pass out at the gate he bit at them, and drove them back. Then Connor knew that his friend the wolf had kept his word. So he let the cows go quietly back to the field; and there they remained, and grew to be the finest in the whole country, and their descendants are flourishing to this day, and Connor grew rich and prospered; for a kind deed is never lost, but brings good luck to the doer for evermore, as the old proverb says:

But never again did Connor find that desolate heath or that lone20 shieling, though he sought far and wide, to return his thanks, as was due to the friendly wolves; nor did he ever again meet any of the family, though he mourned much whenever a slaughtered wolf was brought into the town for the sake of the reward, fearing his excellent friend might be the victim. At that time the wolves in Ireland had increased to such an extent, owing to the desolation of the country by constant wars, that a reward was offered and a high price paid for every wolf’s skin brought into the court of the justiciary; and this was in the time of Queen Elizabeth, when the English troops made ceaseless war against the Irish people, and there were more wolves in Ireland than men; and the dead lay unburied in hundreds on the highways, for there were no hands left to dig them graves.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.