In honor of Black History Month, I am studying the Underground Railroad. During February, I’ll be sharing several books about the Underground Railroad, and I’ll also be examining the theory that the slaves developed a quilt code to help them navigate the route toward freedom. I acknowledge that some scholars reject the thought that there was a quilt code among the slaves. Especially for purposes of this post, I reject that thought.

I am not African American, but I did grow up in the rural South. My mother and my grandmother were quilters, and I have witnessed firsthand the camaraderie of quilters. I do not doubt that the American slaves developed a quilt code, and I am thrilled that I discovered the following book:

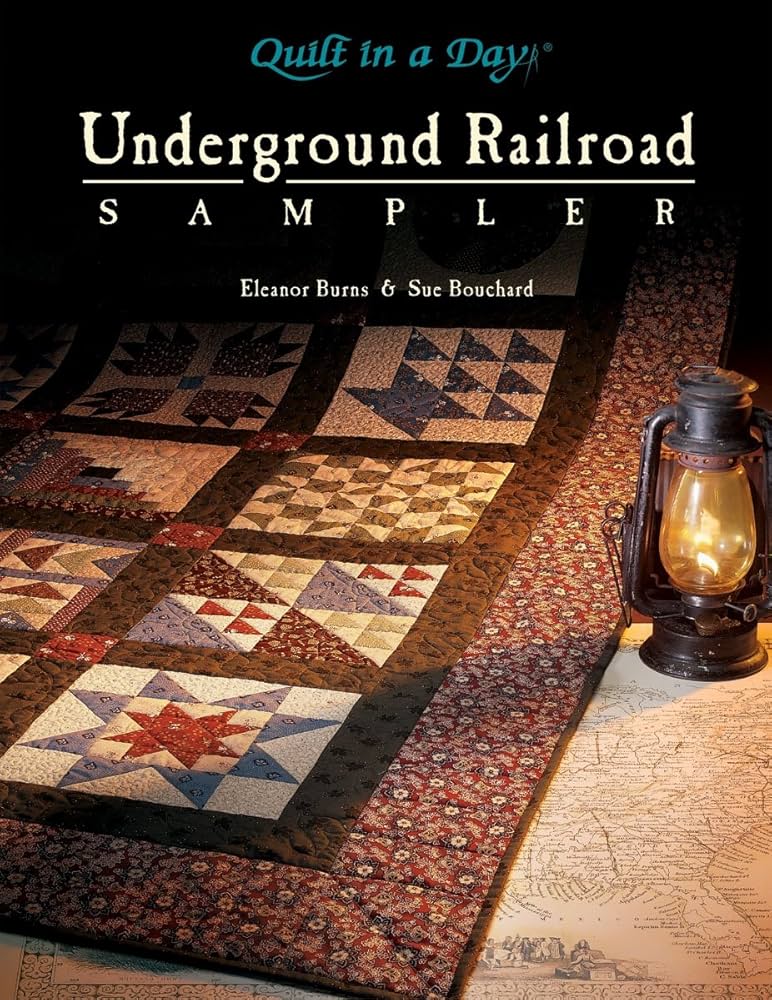

Image Credit: Amazon

“Take a trip on the Underground Railroad! Join Eleanor Burns and Sue Bouchard as they guide you through the story of the Underground Railroad. Learn how fifteen quilt blocks may have played a significant role in communication between the slaves and how it helped them on their way to freedom. The book has 168 full color pages with step-by-step instructions for each of the 15 blocks. There are also directions to make a miniature Underground Railroad quilt. The book contains yardage and cutting charts in addition to fabric identification pages that will assist the quilter in cutting and marking her fabric for this beautiful sampler. “Underground Railroad Sampler” also includes a color page depicting the “Story of the Underground Railroad” that can be photocopied onto Photo Transfer Fabric and included in the quilt.” Quilt in a Day

Patterns included:

Monkey Wrench.

The Monkey Wrench Quilt was the first quilt displayed as a code on the Underground Railroad. It signaled to the Slaves that It Was Time to Gather the Tools Necessary for the Journey Ahead via the Underground Railroad.

“Monkey Wrench – It is time to collect and organize for the trip. Tools, food, any money the slaves possessed should be secured.” freequilt.com

Wagon Wheel

The Wagon Wheel Quilt was the second quilt displayed as a signal for slaves on the Underground Railroad.

“Wagon Wheel – This symbol’s message was to pack up those possessions they had been collecting and get ready for the trip.” freequilt.com

Bear’s Paw

The Bear ‘s Paw Quilt was the third quilt displayed as a signal for slaves on the Underground Railroad.

“Bear Paw – A bear will travel to food and water, so this block advises the slaves to follow literally a bear’s trail through the woods to find something to eat and drink.” freequilt.com

Crossroads

The Crossroads Quilt was the fourth quilt displayed as a signal for slaves on the Underground Railroad.

Crossroads – The crossroads were towns and cities where the travelers could find safety and protection. On the shores of Lake Erie, Cleveland was the main crossroad with a number of overland trails that all came together there. From there water routes to Canada took the slaves to freedom.” freequilt.com

Carpenter’s Wheel

“Carpenter’s Wheel – The carpenter in this case was Jesus. This block, much like the song ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot,’ was a signal to follow directions and travel north to Ohio.” freequilt.com

Basket

“Basket – Food and provisions were always in short supply, and abolitionists would hang this quilt in view to indicate that food and tools were available to those who were in need.” freequilt.com

Log Cabin

Shoo-Fly

Bow Tie

Flying Geese

Birds in the Air

Drunkard’s Path

Sail Boat

North Star

Basket Quilt

The quilt code is remembered this way. The monkey wrench turns the wagon wheel towards Canada

on a bear paw’s trail to the crossroads. Once they got to the crossroads,

they dug a log cabin on the ground. Shoofly told them to dress up

in cotton and satin bow ties, go to the cathedral church, get married,

and exchange double wedding rings. Flying geese stay on the drunkard’s path

and follow the stars. So if you’re a quilter, you may recognize the names of these quilt patterns.

These were 10 patterns that were used to direct slaves to take a particular action.

Each quilt featured one of the 10 patterns. The quilts would be placed on a plantation fence

or a clothes line, one at a time by house slaves. It’s not known exactly how long each quilt would hang,

but it was hung out long enough for everyone to see that the quilt was out and get the message and pass it on.

And since it was common for quilts to be aired outside, the master or the mistress would not be suspicious

seeing the quilts hanging on the line. Each quilt, though, was a message

and signaled a specific action for the slave to take or to consider while the quilt was in view.

These quilt messages would be remembered to use later on on their journey.

The quilt codes had dual meanings, both to prepare to escape and also to give clues

or to indicate directions on the journey. And some of it was a mental preparation too,

not just a physical preparation. My quilt is a sampler of the codes used.

I made it in 2015, and it’s from a book by Eleanor Burns,

who is the founder of the Quilt in a Day empire. The fabric that I used is called Paisley Park

by Kansas Trouble Quilters for Moda.

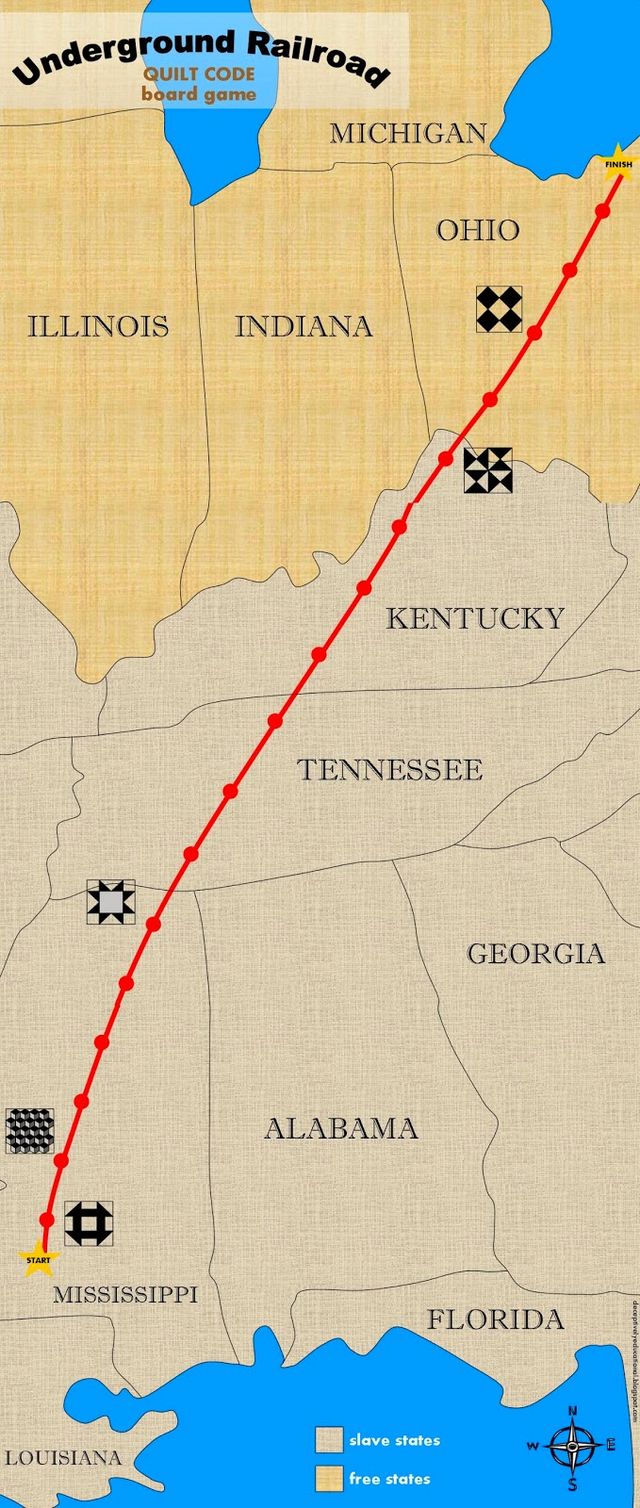

The Underground Railroad

So it begins in the the top left there.

It begins with a quilt pattern that was originally called Jacob’s ladder.

It has been renamed the Underground Railroad pattern. So a sampler quilt was a perfect way

to hide the patterns used and their meaning in plain view. Using one or more of these directional patterns,

or including patterns with identifying landmarks could turn a quilt into a map.

Once the direction was understood, the fugitives were able to travel on.

The Underground Railroad got its name based on a story of a Kentucky slave known Tice.

He was being tracked by a slave holder, and when Tice got to the Ohio River,

there was no boat waiting for him so he jumped into the icy water and began to swim.

And the story goes that he heard the sound of a bell or a call of a bird indicating someone on the other side was waiting for him.

It is said that the slave holder took his eyes off of Tice for just a second, and he vanished.

When the slave holder went back home empty handed, he told everyone it was as if the slave had disappeared

on some kind of underground railroad. The name stuck,

and the journey of slaves escaping to the North has been called this ever since.

The most famous conductor of the Underground Railroad was Harriet Tubman, a former slave.

It is said that she made 19 trips north with runaways and led more than 300 people to freedom.

She became known as Moses to her people. Also, the singing and the humming of certain spirituals

was often done while displaying these special quilts. Singing was another way that messages were shared

and communicated to other plantations. So the code begins with the first block out of the ten.

The Monkey Wrench

It’s called the monkey wrench, and it’s the one with the squares that’s next to the Underground Railroad block.

So the story goes, the monkey wrench turns the wagon wheel towards Canada.

A monkey wrench is a heavy metal tool used by the blacksmith,

and the blacksmith was one of the most knowledgeable persons on the plantation,

and he was also known as the monkey wrench. He might be loaned out to neighboring plantations,

so he knew the lay of the land, and he was often the one to get things started.

So when this monkey wrench quilt was hung out, slaves were to start gathering all of the tools

that they might need on their journey to freedom. The song “Let Us Break Bread Together On Our Knees”

is telling others that the quilt is out, or there’s going to be a secret meeting.

So information about the quilt being on display was also being passed through song

from plantation to plantation, or when slaves would see each other on the road or in town.

The next block in the Underground Railroad code is the wagon wheel, and that’s the circular one.

This pattern, when this quilt was hung out, signaled the slaves to pack their essential things

and provisions for survival as if they were packing a wagon. And also to consider the limited space and the weight.

Wagons were built with hidden compartments and used to transport escaping slaves.

It also is symbolic of a chariot that was to carry them home.

In the fields, slaves may have sung the song “Swing Low Sweet Chariot, Coming to Carry Me Home,”

as these songs contained hidden messages. One of the secondary codes,

not one of the 10 major codes, but one of the secondary codes was the carpenter’s wheel.

So with help from Jesus, the carpenter, and that’s the one with the stars.

Carpenters Wheel

I don’t know if you can see all of it. The stars in right corner there.

To the slave, the master carpenter in their lives was Jesus.

This is a secondary code and pattern, and it was also used as a directive to help them plan their escape.

They were to follow the carpenter’s wheel to the west-northwest.

Many spirituals instructed the listener to steal away to Jesus, to run to Jesus,

meaning follow the carpenter’s wheel to the west-northwest. Plantation owners thought

they were just talking about heaven or singing about heaven. And it is also believed that most of the journeys

began in the springtime when it would be heavy rains, and that aided the slaves in their journey

and from being detected. The lyrics in the song “Steal Away” says,

“My Lord calls me by the thunder,” and this told them to leave in the rainstorm

so dogs won’t have a scent to follow, and their footprints would be washed away.

So the lyrics in that song also include, “green trees bending,” referencing summer, referring to summer,

“the tombstones bursting,” meaning hiding in a graveyard, and, “the Lord, He calls me by the lightning,”

which would illuminate the landscape. And lastly, “the trumpet sounds within my soul,

I ain’t got long to stay here.” They were singing about freedom.

Bears Paw

The third block is the bear’s paw, here.

Slaves were to follow the actual trail of a bear’s footprints,

indicating the best path through the Appalachian mountains. It would be easier to follow the tracks in the spring

when the bears were waking up from hibernation. The mountains ran parallel

to the Underground Railroad route, some of the routes. Following the bear’s paw

would also lead them to a supply of fresh fish and water.

So that was the direction from the bear’s paw. And Native Americans were also very helpful

in providing trails for them to follow. The next one of the secondary blocks

was fill your baskets, and I don’t have that one on the quilt. It’s fill your baskets with enough food and supplies

to get them through on their journey. So they were to pack a sewing basket or a laundry basket,

which would not arouse any anyone’s suspicion if they were to see you carrying it.

Feeding themselves along the way would be difficult. They couldn’t just walk into a store and buy food.

They depended on the safe houses and the abolitionists or their friends along the way.

The Crossroads

The next block is the crossroads,

this one is the basket, and this one is the crossroads. To get them to the crossroads.

So once they made it safely through the mountains, they were to go to the crossroads or a city where they would find protection and refuge.

The main crossroad was Cleveland, Ohio, which was also called Hope,

the most northern spot before they would catch the boat to Canada. Detroit, Michigan was also a crossroads.

It was called Midnight. Their fugitives could take four or five trails over land

that connected with many of the water routes in the area crossing Lake Erie into Canada.

At this crossroad, a decision needed to be made whether to continue on to Canada or to stay in Ohio,

as you may never be able to come back and see your family again.

The fifth block was the log cabin block, a very familiar block to quilters.

Once they got to the crossroads, they dug a log cabin on the ground.

So it is a reference to safe houses along the way, usually a light would be hanging in the window,

that was ran by abolitionists or sympathizers. Traditionally, log cabin quilts have a red center

representing the fireplace or the hearth of the home. It is believed a log cabin quilt hanging with a black center

or a yellow center was a safe house. William Still, who was also a famous

Underground Railroad conductor in Philadelphia, had a log cabin quilt in his home with a yellow center.

And when I was talking about the monkey wrench, Frederick Douglass, it was a quilt that hung in his home

that used a monkey wrench block, a monkey wrench pattern.

shoofly

The sixth pattern is called shoofly,

all the squares here. Shoofly told them, and it was believed that shoofly was an actual person,

possibly even Harriet Tubman herself or others who helped slaves to escape.

Free Blacks and members of the Prince Hall Mason Society

also assisted runaway slaves. They hid them in churches and in caves,

in cellars, in walls, any place that they could.

And graveyards even, especially if they were on the outskirts of town or near a river.

And the seventh number, block number seven or pattern number seven,

was the bow tie block. Shoofly told them to dress up in cotton and satin bows

and go to the cathedral church, get married, and exchange double wedding rings.

So the wedding ring is another quilt pattern.

But slave clothing was often worn and tattered,

old, dirty, all of those things. And it would easily give away their status

as runaway slaves. So this quit pattern was telling them to dress up,

to change clothes. Free Blacks would meet the slaves

in a safe place like a church and give them fresh clothing.

And in my research, I found too that there were a lot of sewing circles of abolitionary women and sympathizers, white sympathizers,

who provided clothes and underwear to assist runaway slaves.

And they would mail them to the safe houses and different Underground Railroad stations in the area

so that they would have fresh clothes to wear. Wearing dresses and sun bonnets and satin bows,

runaways then wouldn’t stand out among city folks, and it was easier for them then to walk through the town

to waiting ships. That sun bonnet is another pattern.

Sun bonnet Sue, if you’re a quilter, you know what that looks like, the bonnets,

like Little House kind of on the Prairie bonnets. And they had long bills on the front of them.

It was said in, I wanna say Wisconsin, but don’t quote me on that, that there was a pastor

that was an abolitionist and helped. And he would go into town with two women

wearing these sun bonnets, and he would come back. He’d still have these two women with sun bonnets,

but no one would notice that when he returned, those women had brown faces

because of the bonnets that they wore, covering their heads.

pinwheel

So when you look at this bow tie block, the quadrant, the quadrants, I can’t say that word,

on the bow tie block, they represent morning, midday, evening, and night.

When the block is turned on its side, it presents an hourglass shape,

meaning manage your time wisely. People are waiting to help you.

And then you can see a pinwheel shape in here,

a pinwheel. And that pinwheel shape is also a pattern

called broken dishes. It is formed in the center. And this pattern had the potential of forming a compass

or a sundial in the cloth and providing directions to the slave of which way to go.

I talked about the double wedding rings. That block is not in my quilt, but I recently learned

in a Smithsonian documentary regarding slavery that runaways would get married,

not just jumping the broom, symbolic of marriage, but they would actually get married as they were more likely to be considered free Blacks

if they had a marriage certificate. Block number eight is flying geese.

flying beasts

Geese fly north in the spring and in the summer, and so this quilt could indicate direction

if they used different colored fabrics. It could indicate direction. And it was also the best time for slaves to escape.

Geese have to stop at waterways in order to rest and to eat. And since they make loud honking noises,

it was easy for runaway slaves to follow their flight patterns. So this block would be sewn in a counterclockwise direction,

north, west, south, east. It was another way that a quilt could indicate direction

or act as a compass, using fabric to make one of the set of keys

different from the others and provide an indication of which way to go.

birds in the air

The next block, birds in the air, this is a secondary block. It wasn’t one of the major blocks, it’s a secondary block,

but it was another block symbolizing flight and migration and direction

for indicating which way for the slaves to go.

The ninth block in the codes was the drunkard’s path.

You can see that, adjust it just a little bit, part of the drunkard’s path.

Blind geese stay on the drunkard’s path. So following a drunkard’s path was a warning for slaves

to weave back and forth, never moving in a straight line.

They would even double back on their tracks to confuse slave hunters with dogs

that might be pursuing them. And I also learned that there’s a well-documented crooked line from Charleston, South Carolina

to Wheeling, West Virginia that was a major crossing place for slaves escaping to Virginia through the mountains.

The fugitive stayed on the drunkard’s path and followed the stars. And it’s said that safes houses

were also staggered in a crooked path. They weren’t always in a straight line from one to the next.

The next code is the sailboat.

Take the sailboat across the Great Lakes. The Underground Railroad used many routes,

by sea, by lake, by river, by canals.

Black sailors and white ship owners helped slaves escape,

hiding them on board their ships, passing on directions and messages from family

that was waiting for them in freedom. They were an important link in the grapevine

between slaves in the South, again, who were forbidden to read or write,

and their free counterparts in the North. The Compromise of 1850,

which was a law that strengthened the Fugitive Slave Act

and it allowed slave holders to pursue and retrieve runaway slaves in Northern states

and free territories. So runaway slaves were not safe until they actually reached Canada,

so many depended on ships and ferries to cross the Great Lakes.

And then the 10th star, the 10th pattern, was the North Star,

and that was the last instruction, follow the star. Like the Star of Bethlehem guiding the Wise Men,

the North Star has been historically connected with the Underground Railroad.

The North Star was the guiding light leading slaves to Canada and to freedom.

The Big Dipper or the Drinking Gourd always points to the North Star in the handle of the Little Dipper.

This eight point star is also called the Evening Star, and it is honored as a guiding light for fugitive slaves.

There is no song that’s more connected to the Underground Railroad than the song called “Follow the Drinking Gourd.”

“Follow the drinking gourd.” There is another secondary pattern

that I don’t have in my quilt. It’s called tumbling blocks. It looks like baby blocks or building blocks,

and it may have been one of the last quilts that was used or one of the last quilts that was hung out.

And then when that quilt showed up, the slaves knew that it was time to escape.

It was time to go. It’s time to tumble out of your life, tumble out of your role.

The conductor is here. Are you ready to go?

Barnacles

So those are the codes in my quilt. And this square here is just a block or a key

that tells the story of that I read to you later about the quilt code.

The monkey wrench turns the wagon wheel and so on and so forth.

I also learned, too, many of you may be familiar with barn quilts.

It’s believed that that whole practice of painting quilt patterns onto wood

and then hanging them onto barns originated in Pennsylvania and then it spread to other colonies.

During the Revolutionary War, barn quilts were used to show American forces

that an area was safe or secure and supplies were available.

And years later during the Civil War, it is reported that the Underground Railroad

used barn quilts for the same purposes, to show safe places.

I found that very interesting. I had not heard that before. But after the Civil War, many African American women

went to work in households as domestics, while others helped out on small farms.

And quilts were made for everyday use out of necessity.

Scraps of clothing, discarded clothing, feed sacks, any kind of fabric was used to make a quilt.

String quilts were real popular, strips of fabric sewn together and then cut into blocks

and made into a quilt. So quilt making has continued in the African American community,

and today’s quilts tell stories of a struggle for achievement

and African American history makers. Story quilts and art quilts are a new category.

And there’s some amazing artists out there. While some African Americans are making stunning art quilts,

and there’s some links in your chat box of some of those, people like Bisa Butler,

many are still making quilts the old way, the same old way. And new patterns that quilters in general enjoy.

African American quilters over the last 40 years have participated in traditions established by their families and communities

while also developing new ones. Black women today are also making quilts

that reflect African culture. Makers, historians, and artists are always using quilts

to raise awareness about African American culture, and they do that in quilts.

I was blessed to attend the modern quilt conference called QuiltCon for 2023

this year in February in Atlanta, and the featured speaker was Chawne Kimber.

She is a dean of mathematics at a liberal arts college.

That’s her profession by day. But she is a renowned quilter also that quilts by hands,

and all of her quilts have a message about overcoming,

about the struggle, those kinds of things. And it was, I don’t know if it was the first time

they’d had an African American keynote speaker, but certainly one in recent years.

And the attendance by African American quilters was beyond amazing,

and I was really privileged to be one of them.

There is a move, I guess I would say, for more diversity

of African Americans being included in quilt guilds and sewing circles and those kinds of things.

We’ve always quilted, always, but we weren’t always invited to participate in the larger community, quilt community.

And we’re seeing more and more of that, I’m pleased to say.

So again, I don’t claim to be any kind of an expert on any of this,

it’s just some things that I learned along the way and I found it very interesting

and I’m happy to share it with you tonight. There’s some resources in your chat box,

and if you have questions, I’m free to answer questions that you might have.

I thank you for your time. Thank you for listening. – [Angela] Hi Georgia, this is Angela.

Questions

I’m gonna jump in. Ruth may be having just a little technical difficulty,

but we have a lot of questions coming in here, so let me take a look.

There was a little bit of a lag.

How did- – [Ruth] You know, Angela, I got my sound back, so I’m able to jump in. – Fantastic.

– [Ruth] Sorry, I bumped my little widget and it just turned my sound off.

Georgia, I’m gonna start off with a compliment. Someone said, “Your quilting pattern is beautiful.”

Were the quilting stitches also used for messages as well as, you know, the fabric piecing?

– There is some information in the book “Hidden in Plain View” that stitches were used.

Even the knots that they tied when they bound the quilt together contained a message.

So there’s quite a bit of information in here. As I said, there’s some controversy

over whether or not that actually happened, but you can read it for yourself.

But yes, they were stitching so much to the fact that they could actually show a map.

If you turned the quilt over, it was a map of the layout of the land, of which buildings that they should look out for

or landmarks that they should look out for. So yes, it was used in that way.

– [Ruth] Thank you. Now here’s another question. Lots of comments saying the quilt is very beautiful.

One person asks, “When someone put out a quilt for the escaping slaves, was it usually just one of the patterns on the quilt?”

– To my knowledge, one quilt would have one patch all over.

All the blocks would be that. But they were to take from that, like from the monkey wrench,

that whole quilt would be the monkey wrench block. But it was an indication or a signal

for those that were planning to run away to get prepared, start gathering your tools,

whatever it is that you’re going to need on that trip. Start getting those things together.

So yes, and one at a time they would be hung out. Again, I don’t know how long they would hang,

but long enough for people to know that it was there, to share the message that the quilt was there,

and start getting ready. And then the next one would be hung out.

– [Ruth] Thank you so much. There’s a couple people that didn’t catch certain blocks,

so somebody said, “I didn’t catch which block was the second block.” If you could review that?

– Jacob’s ladder, or which is now called the Underground Railroad block.

And then there’s the monkey wrench. That was the one where the blacksmith,

who was called the monkey wrench. He was the one that was loaned out to other lands and other properties,

so he knew the lay of the land. He was more likely to know what was outside of the plantation that he worked on.

And then the wagon wheel, just talking about the wagons

and getting things prepared to get in the wagon. Many times there were hidden compartments in the wagon,

so you had to consider the space and what you were taking along.

And remember that the slaves were the ones that probably built the wagon, so they were building these compartments in the wagon

for them to be used to carry people to freedom. And then the carpenter’s wheel, and that block,

it just represents their dependence on their faith and their religion to get them through.

And I have to say, when I was making that block, that block has more pieces than any of the others.

I think there are over 30 pieces in that block,

the carpenter’s wheel. And I was so intrigued sometimes by some of these blocks

as I made the quilt that I took pictures of the backside of the block

as I finished it, because it was just amazing to me

what it looked like from the backside with all these pieces. So I captured it that way.

And then the bear’s paw, the bear’s paw, the basket,

the crossroads, the log cabin. And as you see, my log cabin has a black center.

Normally, they would have a red center. But as a quilt code, it was either black or it was yellow.

And then shoofly, and bow tie, the bow tie,

the flying geese. And if you’re a quilter, you’re like me, I don’t like make flying geese.

They’re difficult, but I got through it. And then the birds in the air,

which it can be another directional quilt block showing which way to go.

And then the drunkard’s path on the bottom, meaning to stagger your path.

And then the boat, and then the star.

How did you get started

– [Ruth] All right, thank you so much. Now, there’s a lot of questions about your quilting.

They said, “How did you get started?” “Who taught you to quilt?” “Did you learn from an ancestor?”

– As I said, I started sewing very young. My mother was an excellent seamstress.

She didn’t really do quilts, but I have to remember, I can remember as a young girl,

my mom and her friends getting together and the quilt frame hanging from the ceiling

and all the ladies hand stitching. I can remember that. I don’t know how old I was, but I can remember that.

But she taught me to sew, and I made garments for myself for many, many years.

And I made lots and lots of baby quilts, but for some reason I didn’t consider that quilting,

that was just making a baby quilt. So then when I finally decided, you know, to make a quilt,

this actually was one of the first that I made

because I was just interested in it. And then I found out that I really love quilting,

and so I’ve made many. My goal is to make them for my family and friends,

so I don’t keep them. There are very few that I actually keep, and this one was really special to me, so I kept it.

But most of them I’ve given away. And most people, I have a long list

of people that want me to make them a quilt, so I tell them, I add them to the list,

but I don’t tell them when it’s coming. I don’t tell ’em I’m working on it or anything.

It just shows up in the mail and people are are thrilled.

But I learned to sew very young, and probably quilting maybe in earnest

for the last 10 years or so. But my mom- – [Ruth] Oh, thank you.

Somebody just shared a link to a great quilt show in North Carolina,

and I’m going to see if I can pop that in the chat box here.

Okay, excellent. Let’s see.

So somebody asked the question, I don’t know if this is within the scope of your talk,

but they asked, “I don’t quite understand how some slaves would help others escape but not leave themselves.”

– Not everybody that helped was a slave. Some of them were free people.

And some of them, they may have even been free themselves, but continued to work on the farms where they were.

You know, I guess when I say slaves helping slaves,

I think the main thing was the secrecy and the keeping quiet about people’s plans,

or about the codes or the quilts or whatever they were doing.

Not everybody had an opportunity to plan it in advance. Some people certainly ran on spur of the moment.

Maybe something happened that got them started or caused them to want to run,

maybe like the sale of a relative or something like that. So everything wasn’t always planned,

but some of them were planned. So not everybody was brave enough

or had enough courage to run, but you certainly weren’t going to discourage anyone else from going

or keep them from going or tell on them for going. I’m sure some of that happened too,

but that’s how they helped one another.

– [Ruth] Thank you so much. There’s a comment that says, “Native American blankets sold at trading posts

also had a language. Fiber art is powerful.” – Yes. – [Ruth] All right, let’s see.

Here’s another question about putting out the quilts.

“Were quilts put out at lots of houses or at one particular house? How would you know where to look for the cues?

How did the enslaved people know what each quilt square meant

in order to understand the hidden messages?” – Yeah, and I think that was the purpose of hanging them out and leaving them out for a while,

so that people would know what the codes were, what they meant, and when to get ready, how to get ready,

that kind of thing. And remember, I think it was plantation by plantation.

And maybe if your plantation wasn’t big enough, maybe the word got out through, as I said,

the singing or slaves going from one plantation to another, they passed the word along,

or even secret meetings where these kinds of things would be discussed.

So I don’t know if it was just one place or many places. I can imagine, like for Harriet Tubman,

when she would come back to carry others away, did she just go to one plantation?

Did she go to several? How did the word get passed that she was back and when she’s ready to take another load?

There’s still a lot of questions that I don’t know. They may be answered somewhere.

There are many, many books that talk about the Underground Railroad and how that worked and who helped.

So the answer may be there someplace, but I don’t have a definitive answer.

– [Ruth] Yes, and somebody dropped a comment in the chat that some chose to stay because they had families

that they couldn’t leave behind. And she references a book, “Finding Your Roots,”

for that fact, yeah. – And some left even though they had families.

They left because they wanted better for their family, and they figured if they could get out and get free,

then they could free the others, or even earn enough money of their own

so that they could buy their loved ones’ freedom. And many did that, many did that.

They ran to freedom, earned the money to buy them. – [Ruth] There are a couple books

I’m thinking of as we’re talking about this. For the younger viewers or listeners today,

“Elijah of Buxton” by, I think his name is Christopher Paul Curtis.

It has a lot of insight into the Underground Railroad,

getting to Canada, and then having to go back down to help somebody else come up.

And then for grownups, Ta-Nehisi Coates book “The Water Dancer”

has so much insight into the Underground Railroad. So those are my two librarian recommendations.

Let’s see. – And when some of the slave laws changed, not everyone stayed in Canada.

Some of them came back to the States when some of the laws changed.

So there was no fear then of being, you know, enslaved again. – [Ruth] Yeah, I’m just dropping a couple titles in there.

Titles

Oh, somebody wants to know, do you do your own quilting or do you send it out to be done?

Quilting

– This quilt I sent out to have it done. I have a very fine longarmer here in the city where I live

that does an awesome job, and she likes the variety of things that I bring to her.

But during COVID, I did buy myself a longarm machine.

I’m still learning to use it, but I have done about three quilts on it, I think.

So it’s still a little intimidating. I’m still learning.

It’s like after you put so much time into piecing together something like this,

I don’t wanna ruin it with bad stitching. So I’m learning, I’m learning, but I do.

I have done some myself, but probably the majority of them I have sent out to a longarm.

– [Ruth] Oh, here’s a great comment in the chat. “Another great book about slaves who remained in slavery due to family,”

in the title is, “Family Bonds: Free Blacks and Re-enslavement Law

in Antebellum Virginia” by Ted Maris-Wolf. So I will go ahead and drop that into the chat

so that everybody can see that. And there’s another question, “Was there still a need to flee after the emancipation?”

Juneteenth

– That’s a good question.

Well, we’re getting ready to celebrate Juneteenth, June 19th, it’s called Juneteenth.

If you’ve not heard of it, it’s now a national holiday. But celebrates the day

that the slaves in Galveston, Texas

were told that they were emancipated.

The message came two years after the signing, but because landowners there

didn’t want them to know because they wanted that labor for as long as they could. But the soldiers came and advised them

of their freedom, of emancipation. And that’s why we celebrate Juneteenth every year.

So there were still some reasons to head North because of Jim Crow,

because of the sharecropping that was so one-sided people could not make a living.

Even though they were free, they could not make a living because of the way things were.

So, many still left and migrated to the North, hoping for more opportunity.

– [Ruth] Thank you. We’re getting towards the end,

but I just love having you here and I’m going to keep asking you questions as they keep rolling in.

Somebody asks, “Why is the book controversial?” And I think they’re referring to the book “Hidden in Plain View.”

– Yes, a lot of people say, well, the story or the claim of codes

cannot be corroborated. There’s no documentation. Or they say these patterns didn’t exist at that time.

Things like that. So there’s a lot of controversy. Did it really happen?

Were codes really used? In the book, it talks a lot about some of these patterns

looking like African symbols, so whether they’ve morphed over time, did they always look like this?

I don’t know. Did they look similar, and over time they’ve looked like this?

I don’t know. But that’s the biggest thing is that they can’t say for sure

that it really happened. And that’s why I talk about the oral tradition

that everything was not written down. Some things were passed along generation to generation.

So I, for one, believe that this is totally possible

that it could have happened. Maybe not exactly like she says here,

but I believe that it could have happened, yes. But that’s the controversy.

– [Ruth] Thank you. I’m dropping a few more links in the chat because before we started,

we were talking about some different resources and one was,

you know, the primary account of William Still. He wrote about the Underground Railroad in the 1870s,

which is, you know, it’s from that era. So I just wonder. Some of the links are not coming through,

but my assistant Angela’s helping me. And we have a great book in the system

called “Fleeing for Freedom: Stories of the Underground Railroad,” as told by Levi Coffin and William Still.

So there’ll probably be a big hold queue forming for that book. There’s already a giant queue for “Hidden in Plain View.”

But I just want you to know there’s a lot of interesting things in our collection. I also popped a couple of articles in the chat.

One is a feature article on the Underground Railroad from the National Geographic, 1984.

And it’s kind of amazing. In that article, a man recalls talking to his grandfather

about his great-grandfather who escaped from slavery and experienced traveling the Underground Railroad

from Delaware up to Canada. So this is to just direct you to some other resources

that are going to give you some more background, and also to let you know that you can link

to some pretty amazing resources through Sno-Isle’s website. So a little…

Wrap Up

– And I probably (indistinct) go so far as to say that everybody used the quilt codes.

People were coming from all over, from Texas all the way over to the Carolinas.

They were coming from all over, so not everybody used the same methods or the same routes,

but they used what was available. – [Ruth] Okay, and as we’re getting

a little closer to wrapping up, we’ve gotten a couple of questions

asking about how to access all of these links after the presentation.

I’ve just popped something into the chat that is a list I started to build in our catalog,

and it lists the books that Georgia recommends and some really great local quilting groups

and nationwide quilting groups. And I’ll just keep adding to that list until we have all of the articles and cool things

that we’ve shared tonight in that list. So as long as you can access that list,

you can search the catalog, just do a list search, Quilt Codes of the Underground Railroad,

and it’ll come up. And so there’s that. Let’s see if there’s any more.

It looks like we’re just getting a lot of thank yous and I don’t see a lot more questions,

so it might be time to go ahead and wrap up.

I will switch gears so I can

go into the closing spiel. So I just wanna thank you so much

for this great presentation, Georgia. It’s just wonderful to have a local treasure here in Snohomish County,

and I just appreciate you sharing your time and your expertise. It’s just been wonderful.

Before we wrap up, I wanna thank everyone in the audience

for joining us this evening and for submitting your questions and comments.

I hope you enjoyed the program. This event has been recorded and will be available on Sno-Isle Library’s YouTube channel

in a week or two. You can find recordings of other past events

by visiting Sno-Isle’s website, clicking on Events, then clicking on Event Recordings.

And with that, I’ll say goodnight, everyone. Thank you so much.

– Goodnight.

Log Cabin – The cabin could mean several things. A red center block represented the hearth of the cabin. A black block meant the house from which it hung was a safe house. Yellow meant to watch for a lantern light.

Shoo-Fly – If this design was seen hanging it indicated that someone would aid and temporarily give shelter to the escaping slaves.

Bow Tie – This indicated that the travelers should dress decently to avoid suspicion. During the journey, what few clothes the slaves had would become tattered and threadbare. Abolitionists and free blacks would provide fresh clothing so they could continue without discovery.

Other pattern blocks like Flying Geese, Birds in the Air,Drunkard’s Path and North Star were all used as directional guides, and Sailboat was the quilt block to indicate there were ship owners and free black sailors who would be able to hide them on boats bound for Canada.

Hanjunzhao Retro Floral Fat Quarters Fabric

Boao 3 Pieces 36 x 62 Inch Wide Vintage Floral Cotton Fabric Rose Flowers

Christmas Homespun

Christmas Homespun Fall Homespun

Fall Homespun

Gnognauq Green

Gnognauq Green

Gnognauq Yellow

Aubliss

Dots

Mililanyo 8pcs

Mililanyo 8pcs

Hanjunzhao Vintage Rose Bundle

‘

‘

Hanjunzhao Rose Bundle 2

THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD QUILT CODE

A History of African-American Quilting

from Ancient Practices to the Civil War Times

By Stefanie Bohde

“According to James Norman, from the beginning of human existence, it has been necessary to locate a common link of communication between people. In the Neolithic Era, which is classified as the late Stone Age, languages began to spread. Some six hundred languages were spoken among clansmen in Africa alone, and many more in Europe and the near East. Unfortunately, because many of these clans split or completely disappeared, and because sounds and words fade easily from memory, hundreds of these languages died out without a trace or way of chronicling. Language has assumed many different written forms, which essentially are codes for certain concrete things or abstract ideas. With the rise of ancient civilization, the evolution of a writing system had begun. Pictograms led way to ideograms, which influenced some of the first pho- netic, alphabetic, and syllabic writing systems in history (Nor- man 5–14).

“Today, many different types of code exist, among them sign language, Braille, and Morse Code. All these codes are steeped in ancient tradition. In essence, a clansman carving pictograms into a cave wall and a woman stitching a symbol into a family quilt would be striving to get the same idea [pg. 70] across; both desire to use written language as a bridge be- between humanity. Unknown to most people, quilting has also been a tool for communication and has been a long-standing tradition in many different cultures. Not only were quilts used for utilization purposes, but they also provided women with an outlet for their creativity during a time when it was expected of them to remain relatively docile homemakers. Many women could put together what was called a “Tact Quilt” in a matter of a few days. They would take scraps of old clothing that their family had worn out, cut strips of it (regardless of the color, pattern, or design), and tie it together over whatever filling was deemed fit to keep them warm. Sometimes leaves were used, while other times these housewives employed crushed newspa- pers as the batting. When warmth wasn’t the object, numerous women quilted for decoration or even to keep track of familial records. Marriage quilts often literally determined a woman’s status for marriage. These quilts were truly supposed to be showpieces, demonstrating a woman’s domestic art. Once the quilt was completed, it was shown to the prospective in-laws, and her marriage worth was evaluated. Album quilts were used to keep track of family history. Often, important dates were sewn into the quilt, along with names and important scenes depicting familial events. Often, these quilts told a story. Sometimes if a loved one had died, a piece of his cloth- ing might be used in the quilt composition. No matter what the genre, quilting gave many women a sense of community. According to one author, “it ties us all together, we are the thread, we are the stitch, we form the stitch, and we form the quilt” (qtd. in Castrillo par. 10). A quilting pattern often overlooked in today’s society is the Underground Railroad quilt code. Used during the time of abolition and the Civil War, this visual code sewn into the pattern of quilts readied slaves for their upcoming escape and provided them directions when they were on their way to free- dom. While there were ten different quilts used to guide slaves to safety in free territory, only one was to be employed at a [pg. 71]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.