The Cocoon Harvest

December 29

[From Gibson’s Sharp Eyes: A Ramblers Calendar of Fifty-Two Weeks Among Insects, Birds and Flowers – Originally Published in 1898 and illustrated by William Hamilton Gibson Author and Illustrator.]

NOW is the time to lay up your store of cocoons, looking to those beautiful moths of next: June; and there are and there are two kinds

at least which will prove a sure harvest for your winter walk. For weeks they have been most effectually hidden among the foliage, but now the thickets are full of them in plain sight that is, if your eyes are sharp enough to find them. It always adds to the zest of a walk at any season to

have some particular quest in view a rare flower or bird, an Indian arrow-head, perhaps. And even now, in midwinter, when the wilds are comparatively drear, there are few objects of life more certain to reward your search than the large cocoons of the Attacus Cecropia and the Attacus Prometheus two among our most beautiful and important moths.

The twigs of most thickets are now quite denuded, with only what might appear a stray determined leaf here and there. Often this leaf is precisely what it appears to be, clinging by its stem, or perhaps tangled in a tiny spider’s web which the winds have as yet been unable to sever. Here and there, however, a cluster of two or three will be found which have a suspicious look, and a closer examination discloses that they are but the artful disguise of a living secret within the Cecropiain its warm double cocoon. But there is a great deal of hocus-pocus, too, among these deceptive leaves.

The bunch of leaves often proves a delusion. They are a continual challenge to the analytic eye; a puzzle often only to be settled by so small a factor as their degree of firmness in the wind, a light, beckoning leaf seldom being worth answering. It is often a matter of small skill to tell at a hundred feet distance just which cluster of leaves holds its cocoon.

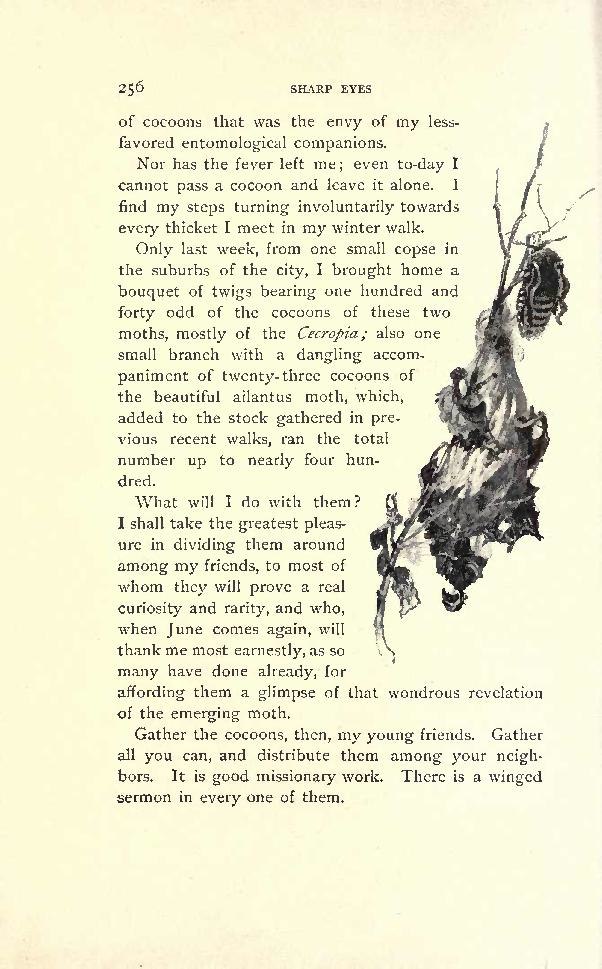

These cocoons vary considerably in size and shape; some being nearly five inches long and very much inflated and bag-like;

others pointed at each end and being more contracted, but always of the toughest of silky gray parchment in texture. They are secured to the twigs by their longest side, and are quite common (especially early in the winter) attended by the few leaves which the caterpillar originally drew together while constructing its silken framework. Occasionally a specimen is found partially incased in a leaf, which leaves a perfect mould of itself in the silk upon removal.

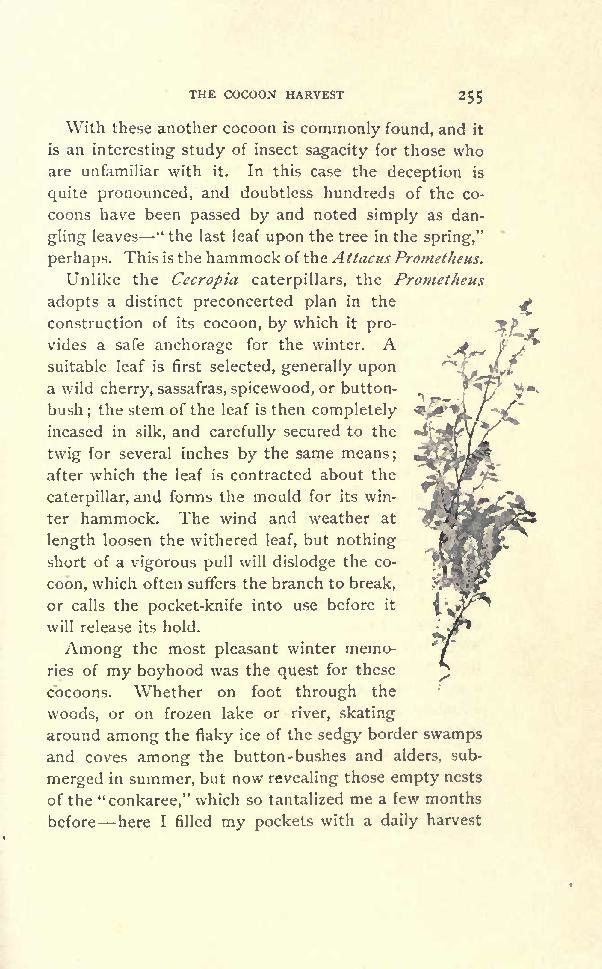

With these another cocoon is commonly found, and it is an interesting study of insect sagacity for those who are unfamiliar with it. In this case the deception is quite pronounced, and doubtless hundreds of the cocoons have been passed by and noted simply as dangling leaves “the last leaf upon the tree in the spring,” perhaps. This is the hammock of the Attacus Prometheus.

Unlike the Cecropia caterpillars, the Prometheus adopts a distinct preconcerted plan in the construction of its cocoon, by which it provides a safe anchorage for the winter. A suitable leaf is first selected, generally upon a wild cherry, sassafras, spicewood, or buttonbush; the stem of the leaf is then completely incased in silk, and carefully secured to the twig for several inches by the same means; after which the leaf is contracted about the

caterpillar, and forms the mould for its winter hammock. The wind and weather at length loosen the withered leaf, but nothing short of a vigorous pull will dislodge the cocoon, which often suffers the branch to break, or calls the pocket-knife into use before it will release its hold

Among the most pleasant winter memories of my boyhood was the quest for these cocoons. Whether on foot through the woods, or on frozen lake or river, skating around among the flaky ice of the sedgy border swamps and coves among the button -bushes and alders, submerged in summer, but now revealing those empty nests of the “conkaree,” which so tantalized me a few months before here I filled my pockets with a daily harvest of cocoons that was the envy of my less favored entomological companions.

Nor has the fever left me; even to-day I cannot pass a cocoon and leave it alone. I find my steps turning involuntarily towards every thicket I meet in my winter walk

Only last week, from one small copse in the suburbs of the city, I brought home a bouquet of twigs bearing one hundred and forty odd of the cocoons of these two moths, mostly of the Cecropia ; also one small branch with a dangling accompaniment of twenty- three cocoons of the beautiful ailantus moth, which, added to the stock gathered in previous recent walks, ran the total number up to nearly four hundred.

What will I do with them? I shall take the greatest pleasure in dividing them around among my friends, to most of whom they will prove a real

curiosity and rarity, and who, when June comes again, will thank me most earnestly, as so many have done already, for affording them a glimpse of that wondrous revelation of the emerging moth.

Gather the cocoons, then, my young friends. Gather all you can, and distribute them among your neighbors. It is good missionary work. There is a winged sermon in every one of them.

https://ia600700.us.archive.org/28/items/sharpeyesrambler00gibsiala/sharpeyesrambler00gibsiala.pdf