IT seems as if the day was not wholly profane in which we have given heed to some natural object. . . .

He who knows the most, he who knows what sweets and virtues are in the ground, the waters, the plants, the heavens, and how to come at these enchantments, is the rich and royal man.

– EMERSON–

HOW BUNNY WRITES HIS AUTOGRAPH

December 22

[From Gibson’s Sharp Eyes: A Ramblers Calendar of Fifty-Two Weeks Among Insects, Birds and Flowers – Originally Published in 1898 and illustrated by William Hamilton Gibson Author and Illustrator.]

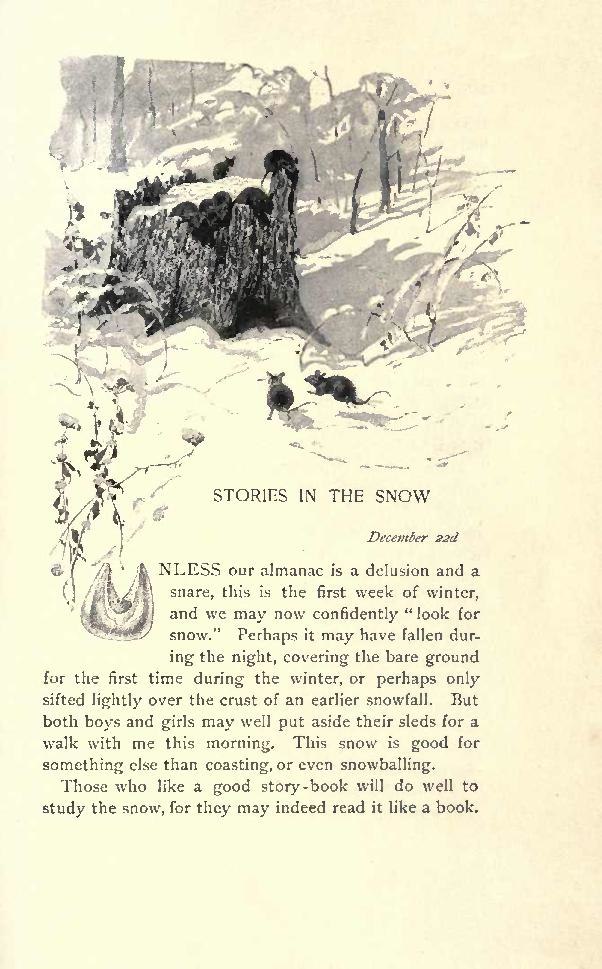

UNLESS our almanac is a delusion and a snare, this is the first week of winter, and we may now confidently “look for snow.” Perhaps it may have fallen during the night, covering the bare ground for the first time during the winter, or perhaps only sifted lightly over the crust of an earlier snowfall. But both boys and girls may well put aside their sleds for a walk with me this morning. This snow is good for something else than coasting, or even snowballing. Those who like a good story-book will do well to study the snow, for they may indeed read it like a book.

It is a great white page storied with the doings of the little wild folk which few of us ever see. Who ever sees a deer-mouset or even a common field-mouse? The summer meadows are full of them, but we should never suspect it, did we not occasionally surprise one scampering away with a squeak before the scythe of the mower, or perhaps jumping like a gray streak from a forkful of new-made hay, or from beneath the cornshock as it is raised to the cart.

Their doings down deep among the summer grass no one ever sees, but it is not so now. From the moment their little whiskered noses peep from their burrows their acts are recorded. They write their autobiography day by day. We can see all the mischief they have been up to during the night, and just what company they have kept.

Here is a well-worn track to a pile of brush near where the snow is all cut up with footpints a favorite rendezvous, evidently; doubtless the gossip

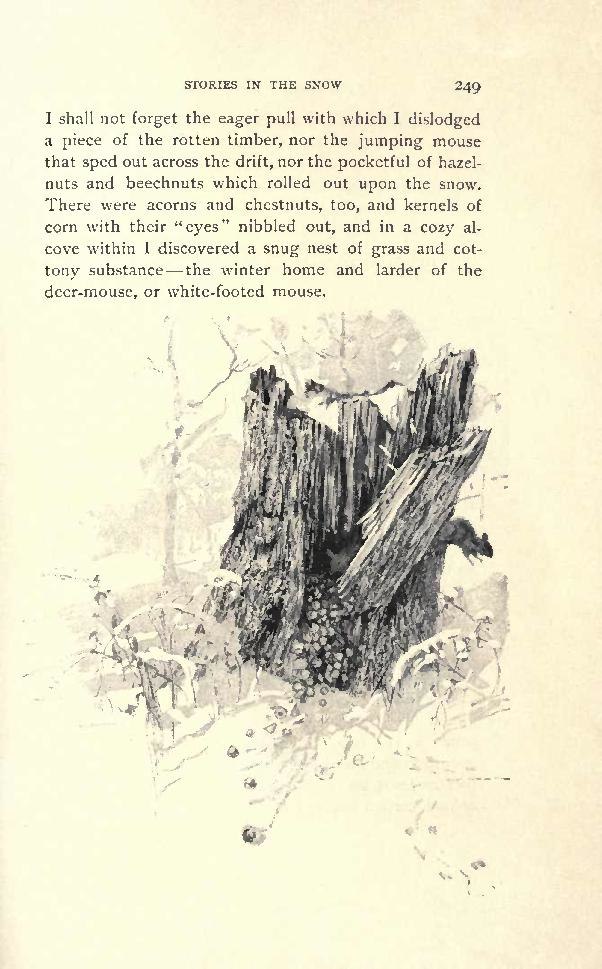

exchange of all the wild bead-eyed folk. Here is a spot among the weeds where four little birds have danced a quadrille or minuet balance corners, forward and backward, chassez, and all hands round. Close by, the snow appears as if sewed with tiny stitches, and here we see two long jumping trails circling about a stump. How alive they seem! telling plainly of a lively race between two mice, both tracks terminating in a hole beneath a stump. The snow on the top of the stump is ruffled with the feet of the furry populace who witnessed the sport, and doubtless cheered on their favorites in their sprightly race. I remember one winter catching sight of a retreating tail whisking into a hole beneath a stump like this, and I shall not forget the eager pull with which I dislodged a piece of the rotten timber, nor the jumping mouse that sped out across the drift, nor the pocketful of hazelnuts and beechnuts which rolled out upon the snow. There were acorns and chestnuts, too, and kernels of corn with their “eyes” nibbled out, and in a cozy alcove within I discovered a snug nest of grass and cottony substance the winter home and larder of the deer-mouse, or white-footed mouse.

THERE are few country boys who do not know those footprints about the box-traps in the woods, and all through the thickets everywhere four in a set. Yes; we all know them; they are the unmistakable seal or signature of the little gray rabbit, or, more properly, hare. And yet I have never met an individual who knew just how bunny writes his autograph. Even though we see him in the act, he writes it so fast that we cannot follow him. It is only by examining it very closely that we can get at the secret.

These footprints are always four in a set ; the two front impressions being about six inches apart, and the other pair quite close together, or even united occasionally, or placed one directly in front of the other; the direction of the hare’s course being plainly seen by the prints of the toes. But it will be a surprise to most people to find on examination that the widely-separated pair in front are really made by the feet of the animal, certain impressions showing plainly the full imprint of the long hind shank even to its heel, or elbow, as this joint of the leg is incorrectly called.

Where the animal has progressed by slow, short jumps ” when the hare limps awkward” the marks of the long soles are frequently to be seen; but

in the more rapid leaps, clearing from one to two yards, only the tips of the feet have touched the snow.

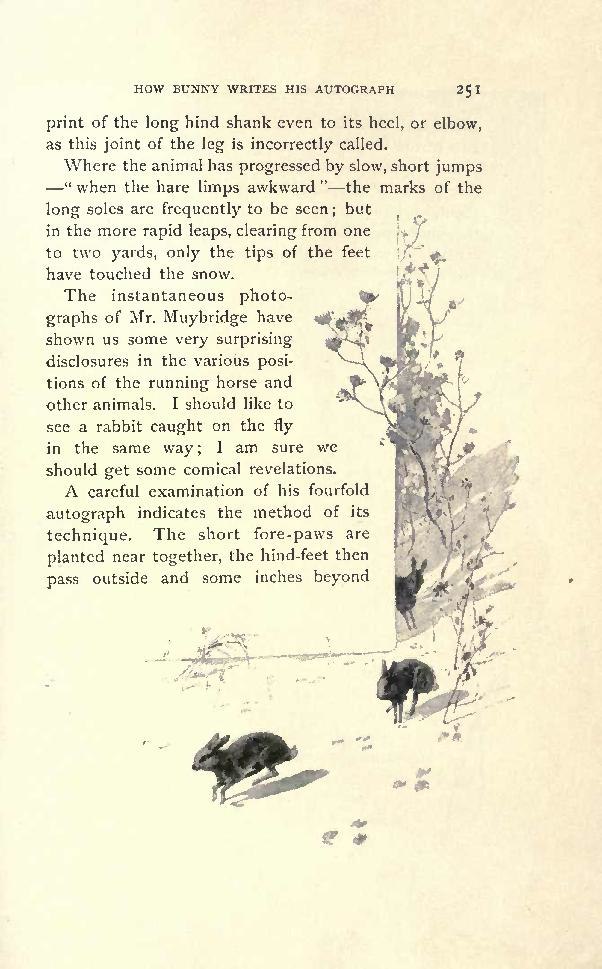

The instantaneous photographs of Mr. Muybridge have shown us some very surprising disclosures in the various positions of the running horse and

other animals. I should like to see a rabbit caught on the fly in the same way; I am sure we should get some comical revelations. A careful examination of his fourfold autograph indicates the method of its technique. The short fore-paws are planted near together, the hind-feet then pass outside and some inches beyond them, and then follows a jump which may vary from two to ten feet. It is quite possible that bunny may really lift his fore-paws by a spring before the hind- legs overtake them, as shown in my foreground hare, but I fancy that the photograph may yet show us some such transitory attitude as we see in the one behind

William Hamiton Gibson, Sharp Eyes: A Rambler’s Calendar of Fifty-Two Weeks Among Insects, Birds, and Flowers. pgs. 248-252.

Gibson, Wm. Hamilton. Sharp Eyes a Rambler’s Calendar: Fifty-Two Weeks Among Insects, Birds, and Flowers. New York, Harper and Brothers Franklin Square, 1898.

https://ia600700.us.archive.org/28/items/sharpeyesrambler00gibsiala/sharpeyesrambler00gibsiala.pdf