Image Credit: Ohio Scenic River Byway

The Cave

History

“From the 1790s to the 1870s, the area around Cave-in-Rock was plagued by what historians as early as the 1830s referred to as the “Ancient Colony of Horse-Thieves, Counterfeiters and Robbers“, and better known today due to Otto Rothert’s history early in the 20th century as the “Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock”.

“In 1790, counterfeiters Philip Alston and John Duff (or John McElduff) used the cave as some type of rendezvous, though details are scarce. Although folklore printed in 19th century histories failed to establish a prior connection between the two men, both had lived in the area of Natchez, Mississippi, at the start of the Revolutionary War. …

Davy Crockett and Mike Fink

“In Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett and the River Pirates, Davy Crockett and Mike Fink anachronistically fight Sam Mason and his pirates. Also, at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom, there is a scene called “Cut-Throat Corner” and “Wilson’s Cave Inn” that can be seen on the bank of the Rivers of America while riding the Liberty Belle Riverboat around Tom Sawyer’s Island. This scene is based upon the real life Cave-In-Rock and the activity of river pirates during that time period.

“A scene of the MGM classic How the West Was Won was filmed at the cave as well as at Battery Rock.[14] In 1997, The History Channel show In Search of History filmed at the site for an episode entitled “River Pirates”. Wikipedia

The “ninth book” of Christopher Ward’s 1932 novel The Strange Adventures of Jonathan Drew; A Rolling Stone is titled “Cave-In-Rock”. The action is set in 1824. Jonathan rescues two slaves duped into running away and working for a gang of dangerous outlaws who use Cave-In-Rock as their base of operations.

L. A. Meyer’s novel Mississippi Jack features the heroine leading an anachronistic raid against river pirates as an homage to the aforementioned Davy Crockett episode.

References

- Coates, Robert M. The outlaw years: the history of the land pirates of the Natchez trace, Macau lay Company, 1930.

- Jackson, Shadrach L. The life of Logan Belt he noted

- Rothert, Otto A. The Outlaws of Cave-In-Rock, Otto A. Rothert, Cleveland 1924; rpt. 1996 ISBN 0-8093-2034-7

- Wagner, Mark and Mary McCorvie. “Going to See the Varmint: Piracy in Myth and Reality on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, 1785-1830,” X Marks the Spot: The Archaeology of Piracy, Univ. Press of Florida, 2006. Wikipedia

Cave In Rock is a nature-made hide-away cut into a rock formation in Southern Illinois–on the Ohio River.

I grew up not far from this area, near the banks of the Mississippi River, where it crawled between the southern parts of Missouri and Tennessee.

Like many people, I have traced the roots of my family and how they came to live in Southeast Missouri, and I have discovered that my people originally settled on the East Coast, and my family’s stories include tales of simple people who inched their ways across rocky passes–ultimately settling in the middle of the country. From what I have discovered, my immediate family made their journey from the East in covered wagons. But many or the pioneers of that era traveled on the Ohio River–until it reached the Mississippi River, and allowed the Mississippi River to carry them the rest of the way home.

Mark Twain’s home, in Hannibal, Missouri, was up the river from where I grew up, and I cut my teeth on tales of river boats and the people who manned them–especially in the 18th and 19th Century.

Today, I happened upon this tale from the area of Cave In Rock, and it carried me back home.

The Truth Is Stranger Than Fiction

“Historical novels, with some exceptions, present the past in a more interesting manner than do the formal histories which are intended as chronicles of actual facts. It has been said, on the one hand, that “truth is stranger than fiction,” and on the other that “fiction is often more truthful than fact.” Fiction is undoubtedly more truthful in the presentation of the manners and social life of the period portrayed than is formal history. The history of Cave-in-Rock and the careers of the outlaws identified with the place is not only stranger than fiction, but is besprinkled with many tragic and melodramatic scenes which, although almost unimaginable, are actually true.

The Cave in Fiction

“For more than a century fiction writers have used the Cave as a background for stories. These authors by freely discarding the leading facts and drawing on their own imaginations wrote stories less original than might otherwise have been produced.

“No effort has been made to compile a more or less complete collection of works of fiction pertaining to the Cave. The stories and poems commented on in the course of this chapter are only such as were incidentally found while in search of history. Although this fiction has very little of facts for a basis, and most of the scenes are far from probable, nevertheless it necessarily stands not only as Cave-in-Rock literature, but also as a contribution to the good, bad, or indifferent literature of America. The fact that more than one edition was published of the Cave-in-Rock novels here referred to322 indicates, to some extent that they represent some of the types of stories then in demand.

Stories dealing with mysterious murders and highway robberies have always found many enthusiastic readers. It seems that every decade of the nineteenth century produced at least one new tale of Cave-in-Rock. And in our own times the writings of some well-known living authors show that the Cave is still supplying material for fiction.

In Irvin S. Cobb’s story “The Dogged Under Dog,” (originally published in the Saturday Evening Post, August 3, 1912, and shortly thereafter printed in Cobb’s book entitled Back Home) one of the characters, recalling some of the rough men who lived near the Cave when that country was still new, says Big Harpe and Little Harpe were run down by dogs and killed and that “the men who killed them cut off their heads and salted them down and packed them both in a piggin of brine, and sent the piggin by a man on horseback up to Frankfort to collect the reward.”

Nancy Huston Banks in Oldfield, 1902, devotes a few pages to Cave-in-Rock, the Harpes, and a character she calls “Alvarado,” a mysterious Spaniard who frequented the lower Ohio valley and who was suspected of having been a comrade of Jean Lafitte. Mrs. Banks, in her next historical novel, ’Round Anvil Rock, 1903 (in which Philip Alston is one of the leading characters) refers to that section of Kentucky lying opposite the Cave as having been the “Rogues Harbor.”

The Harpes, Masons, and the Cave are introduced in The Ark of 1803, by C. A. Stephens. This book for boys, published in 1904, is intended as a picture of romances and tragedies incidental to early navigation on the Ohio and Mississippi. It serves that purpose325 fairly well, although practically no statement made by the author regarding the Harpes and the Masons is in accordance with history or tradition.

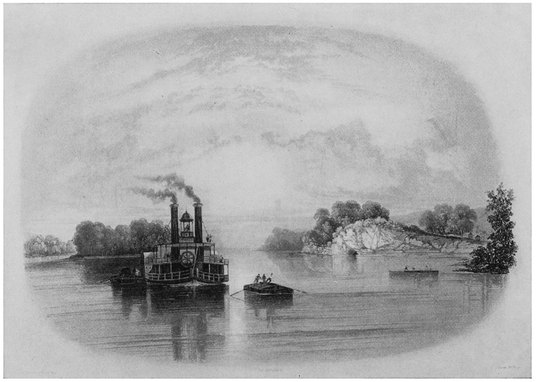

View of Cave-in-Rock and Vicinity, 1833

It shows a landscape interesting in itself but false to the actual scene

(Reproduced from Charles Bodmer’s drawing)

Our earliest item relative to fiction pertaining to the Cave was found in a review published in The Port Folio, February, 1809, of Thomas Ashe’s Travels in America Performed in 1806, printed in London in 1808. The critics in Ashe’s day, and ever since, declared the writer of Travels a literary thief, bone thief, and infamous prevaricator and ridiculed his work on the ground that it was filled with incredible stories grafted onto authentic incidents and actual facts. This general condemnation gave the new book a wide circulation for a few years. The editor of The Port Folio devotes a dozen pages to his “entire contempt both of Mr. Ashe and his work.”

Most of the travelers who appeared after Ashe’s day and examined the Cave detected in his sketch a combination of facts and fiction that helped spread the name and history of this interesting and picturesque rendezvous of outlaws. Many a visitor still goes to the place expecting to explore the “upper cave” but soon discovers that its size has been wildly exaggerated by Ashe. His account of the Cave is one of the longest ever written and will always be of curious interest no matter from what standpoint it may be read, other than history. The reproach to Ashe is that he gave the hoax out as veritable facts encountered in his travels and never corrected this impression or acknowledged his purpose. About half of what he says concerning the Cave is at least highly probable; the remainder is wholly fictitious.

A casual investigation of the stories published after outlawry terminated at Ford’s Ferry, brought to light326 two novels and a long poem in which the Cave serves as a background. Viewed from the standpoint of today their plots have the consistency of a dime novel. Browsing in the field of fiction also led to the discovery of the one time celebrated romance of Harpe’s Head.

Harpe’s Head, by Judge James Hall, was first published in America in 1833, and the following year was printed in London under the title of Kentucky, A Tale. It was later republished in America in Judge Hall’s volume, Legends of the West. Harpe’s Head is the only novel in which the notorious Harpes are introduced as characters. It is a story of a small emigrant family traveling from Virginia to western Kentucky over the route then endangered by the Harpes. All the characters are fictitious, except the two outlaws and their wives. No reference is made to their career at the Cave.

The romance is written in a dignified and graceful style. Atkinson’s Casket for November, 1833, in its comments on the book says “it has some masterly scenes,” and quotes one in full—a Virginia barbecue. Among other interesting sketches of pioneer times woven into Harpe’s Head is one of “Hercules Short” or “Hark Short, the Snake Killer,” a half-witted boy who performs extraordinary feats and who labors under the impression that he is a son of Big Harpe. On one occasion “Hark” remarks that his mother told him, “If anybody was to rake hell with a fine-comb they would not find sich a tarnal villain as Big Harpe.”

Edmund L. Starling, in his History of Henderson County, Kentucky, 1887, says: “The history of the Harpes in this portion of Kentucky, has long ago, and repeatedly found its way into the histories of Kentucky and other states, in pamphlets and the newspapers of327 the country, and at one time was even dramatized for the American stage. But it was so desperate and appalling to all rational sensibilities that it was abandoned by the drama.” I did not find any pamphlets or dramas regarding the Harpes.

The earliest novel found using Cave-in-Rock for a background is Mike Fink, A Legend of the Ohio, by Emerson Bennett, who for a time was a well-known writer of thrilling romances. This melodrama was first published in Cincinnati in 1848, and although now a somewhat rare book, it ranked, judging from the number of editions issued, among widely-read stories of the middle of the last century. Its popularity was not due to any high literary merit, but to its wild and extravagant plot. The greater part of the story deals with bloody battles between a band of outlaws and the flatboat crew and passengers led by Mike Fink. Practically all the action takes place in or near the Cave, and for that reason “A Legend of Cave-in-Rock” would have been a more appropriate subtitle.

Shortly after Mike Fink was put into circulation there appeared in the Alton (Illinois) Courier, 1852, a prize serial entitled Virginia Rose, by Dr. Edward Reynolds Roe. Having gone through a pamphlet edition, this Cave-in-Rock story was published in book form in 1882 under the title of Brought to Bay, and in 1892 the same story was republished and its title changed back to Virginia Rose. Dr. E. R. Roe—not E. P. Roe with whom he is sometimes confused—was a citizen of Illinois, practiced medicine and wrote a number of books. He died in Chicago in 1893 at the age of eighty. He lived in Shawneetown a few years, beginning in 1843, and it is said he prepared the greater part of this manuscript while residing there.

328The book has no preface and the presumption is that all the characters are fictitious. The story deals with the career of a girl, Virginia Rose, who was kidnapped in Shawneetown by her father, the leader of the Cave-in-Rock outlaws. He takes her to the Cave, and it so happened that shortly thereafter the New Madrid earthquake of 1811 occurs. The citizens of Shawneetown, suspecting that the stolen Virginia Rose may have been taken to the Cave, so runs the story, organize a rescuing party. Upon their arrival at the Cave, they, to their great surprise, find the place abandoned. Boxes and barrels were scattered around, their contents undisturbed, and the general appearance indicated that the place had been abandoned suddenly.

In the words of the author: “Remnants of a feast which had never been eaten were lying upon a table; lamps were hanging around burnt out for want of oil…. The hatchway overhead, which communicated with the room above was not closed … but the avenues which led from it to the inner cave had disappeared. The rock had fallen from above in vast masses and closed all connection between the upper cave and the outer world forever…. What was a hill back of the cave bluff now appeared to be a hollow or depression, as compared to the ground around it…. The outlaws had met their fate—they had perished in the earthquake [except the leader and his daughter who were on the Mississippi at the time] perhaps in the midst of gay festivities, perhaps in the hour of music and dancing! Who could say? Not a soul was left to tell the tale. The men who had come to execute vengeance could not now avoid sympathy for the dead.”

Thus did the author of Virginia Rose make the New Madrid earthquake wipe out the Cave-in-Rock’s “inner329 cave” or “upper cave” that had been “discovered” and is so extravagantly described by Thomas Ashe!

Between recorded history on the one hand and stories of fiction on the other stands the book Chronicles of a Kentucky Settlement, 1897, by William Courtney Watts. It is a historical romance based solely on local tradition. Although this work is somewhat faulty in its general construction, and may be, at times, somewhat crude in its literary style, it is, nevertheless, one of the most faithful historical sketches of early Kentucky.

The leading characters are Joseph Watts and Lucinda Haynes, who were first thrown together in 1805 when children on their way from North Carolina to the West, Joseph going to Tennessee and Lucinda moving with her parents to Kentucky. A few years later Joseph Watts began a search for Miss Haynes and found her near Salem, Kentucky. After a courtship such as none but lovers in a new country could experience, they were married and became the parents of the author who tells their story. Among other characters is Charles H. Webb, who gave Watts an account of his capture at Cave-in-Rock and escape from the outlaws and who later married the daughter of James Ford.

The gloomiest tragedy in the book concerns the unfortunate Lucy Jefferson Lewis, sister of Thomas Jefferson, whose two sons killed a slave on their farm near Smithland, Kentucky, and cut up the body in an attempt to conceal their crime. One of the Lewis brothers committed suicide on his mother’s grave and the other escaped after he had been arrested for murder and placed in jail. All the characters in Chronicles are presented under fictitious names.41

It is probable that every person who saw the landscape330 of which the opening of the Cave forms a part had his sense of romance and poetry stirred by the sight. To what extent attempts were made to express this emotion in the form of poetry or verse is not known. Only one poem has been found—“The Outlaw,” by Charles H. Jones, of Cincinnati. It comprises about one thousand two hundred lines, published in 1835 in a neatly bound booklet called The Outlaw and Other Poems. In the October, 1835, issue of the Western Monthly Magazine, of Cincinnati, Judge James Hall devotes two pages to a eulogistic review of the book, encouraging the young poet in his work. A more enthusiastic reviewer might have called this an epic of Cave-in-Rock.

In his introductory note Mr. Jones briefly refers to the then well-known fact that the Cave had been for many years the resort of a band of outlaws all of whom were finally either killed or driven out by the Rangers. As to his authorities he states that “the ravages of the robbers are still fresh in the recollection of many of the inhabitants of the lower Ohio valley.”

About one-half of the poem is an “effervescence of331 poetic fancy,” with here and there a real gem. The plot is dramatic. The story begins in Virginia. Our hero shoots his successful rival in love immediately after the wedding ceremony. Believing he has killed the groom and that the shock has proven fatal to the bride, he flees to the wilds of the West. He drifts down the Ohio, joins the band of outlaws at the Cave and soon becomes their leader—The Outlaw.

One “dark tempestuous night” a flatboat passing the Cave is attacked by the robbers; a fierce and bloody combat follows. The Outlaw discovers among the passengers the very girl who had discarded him for another—and still alive. He stabs her in the heart and then—

The battle continues. The Outlaw kills man after man, when to his surprise he finds himself facing the very man he thought he had killed in Virginia. The two recognize each other instantly. They draw daggers and The Outlaw is slain. And the boatmen, so runs the story, exterminate the band of robbers at the Cave.

332

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.