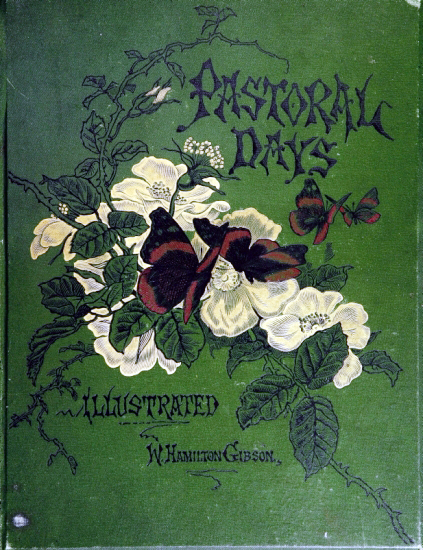

A Pastoral Year – Summer – William Hamilton Gibso

Farther on we see the lily-pond, with its surrounding swamp and its legion of crowded water-plants. Here are rank, massive beds of swamp-cabbage, and lofty cat-tails by the thousand among the bristling bogs of tussock-sedge and bulrush. Here are calamus patches, and alder thickets, and sedges without number; and the prickly carex and blue-flag abound on every side. There are galingales and reeds, and tall and graceful rushes, turtle-head and jointed scouring grass, and horse-tail, besides a host of other old acquaintances, whose faces are familiar, but whose names I never knew. But they were all my friends in boyhood. I knew them in the bud and in the blossom, and even in their winter skeletons, brown and broken in the snow. Near by there is a ditch: you never would know it, for it is completely hidden from view beneath an interlacing growth of jewel-weed. But see that gorgeous mass of deep scarlet that floods the farther bank! Nowhere within a circuit of miles around is there such a regal display of cardinal flowers as this: skirting the borders of the ditch for rods and rods, clustering about a ruined, tumbling fence, whose moss-grown pickets are almost hidden in the dense profusion of bloom.

Then there is its airy companion, the “touch-me-not,” with its translucent, juicy stem, and its queer little golden flowers with spotted throats—the “jewel-weed” we used to call it. I know not why, unless from the magic of its leaf, which, when held beneath the water, was transformed to iridescent frosted silver. We all remember its sensitive, jumping seed-pods, that burst even at our approach for fear that we should touch them; but no one can fully appreciate the beauty of the plant who has not seen its silvery leaf beneath the water. Here it justifies its name, for it is indeed a jewel

How often in those olden times have I lain down among these bulrushes and sedges near the lily pond, and listened to the buzzing songs of the crickets and the tiny katydids that swarmed the growth about me, and filled the air with their incessant din. I remember the little colony of ants that picked their way among the rushes; that gauzy dragon-fly too, that circled and dodged about the water’s edge, now skimming close upon the surface, now darting out of sight, or perhaps alighting on an overhanging sedge, as motionless as a mounted specimen, with wings aslant and fully spread. “Devil’s darning-needles” they were called. The devil may well be proud of them; for darning-needles of such precious metals and such exquisite design are rare indeed. They were of several sizes too. Some were large, and flashed the azure of the sapphire; others fluttered by with smoky, pearly wings, and slender bodies glittering in the light like animated emeralds: and another I well remember, a little airy thing, with a glistening sunbeam for a body, and wings of tiny rainbows

We used to call him “Professor Wiggler,” owing to an hereditary nervous habit of wiggling his head from side to side when not otherwise employed. To this little humpbacked creature I am indebted for a great deal of past amusement. Distinctly I remember the whack-whack-whack on the inside of the old pasteboard box as the captive pets threatened to dash out their brains in their demonstrations at my approach. Professor Wiggler is really a most remarkable insect, as one might readily imagine from his scientific name, for in learned circles this individual is known as Mr. Gramatophora Trisignata. He has many strange eccentricities. At each moult of the skin he retains the shell of his former head on a long vertical filament. Two or three thus accumulate, and, as a consequence, in his maturer years he looks up to the head he wore when he was a youngster, and ponders on the flight of time and the hollowness of earthly things, or perhaps congratulates himself on the increased contents of his present shell. When fully grown, he stops eating, and goes into a new business. Selecting a suitable twig, he gnaws a cylindrical hole to its centre and follows the pith, now and then backing out of the tunnel, and dropping the excavated material in the form of little balls of sawdust.

We used to call him “Professor Wiggler,” owing to an hereditary nervous habit of wiggling his head from side to side when not otherwise employed. To this little humpbacked creature I am indebted for a great deal of past amusement. Distinctly I remember the whack-whack-whack on the inside of the old pasteboard box as the captive pets threatened to dash out their brains in their demonstrations at my approach. Professor Wiggler is really a most remarkable insect, as one might readily imagine from his scientific name, for in learned circles this individual is known as Mr. Gramatophora Trisignata. He has many strange eccentricities. At each moult of the skin he retains the shell of his former head on a long vertical filament. Two or three thus accumulate, and, as a consequence, in his maturer years he looks up to the head he wore when he was a youngster, and ponders on the flight of time and the hollowness of earthly things, or perhaps congratulates himself on the increased contents of his present shell. When fully grown, he stops eating, and goes into a new business. Selecting a suitable twig, he gnaws a cylindrical hole to its centre and follows the pith, now and then backing out of the tunnel, and dropping the excavated material in the form of little balls of sawdust.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.