Eye Spy: Afield with Nature Among Flowers and Animate Things

Wm Hamilton Gibson

PUBLISHED 1899

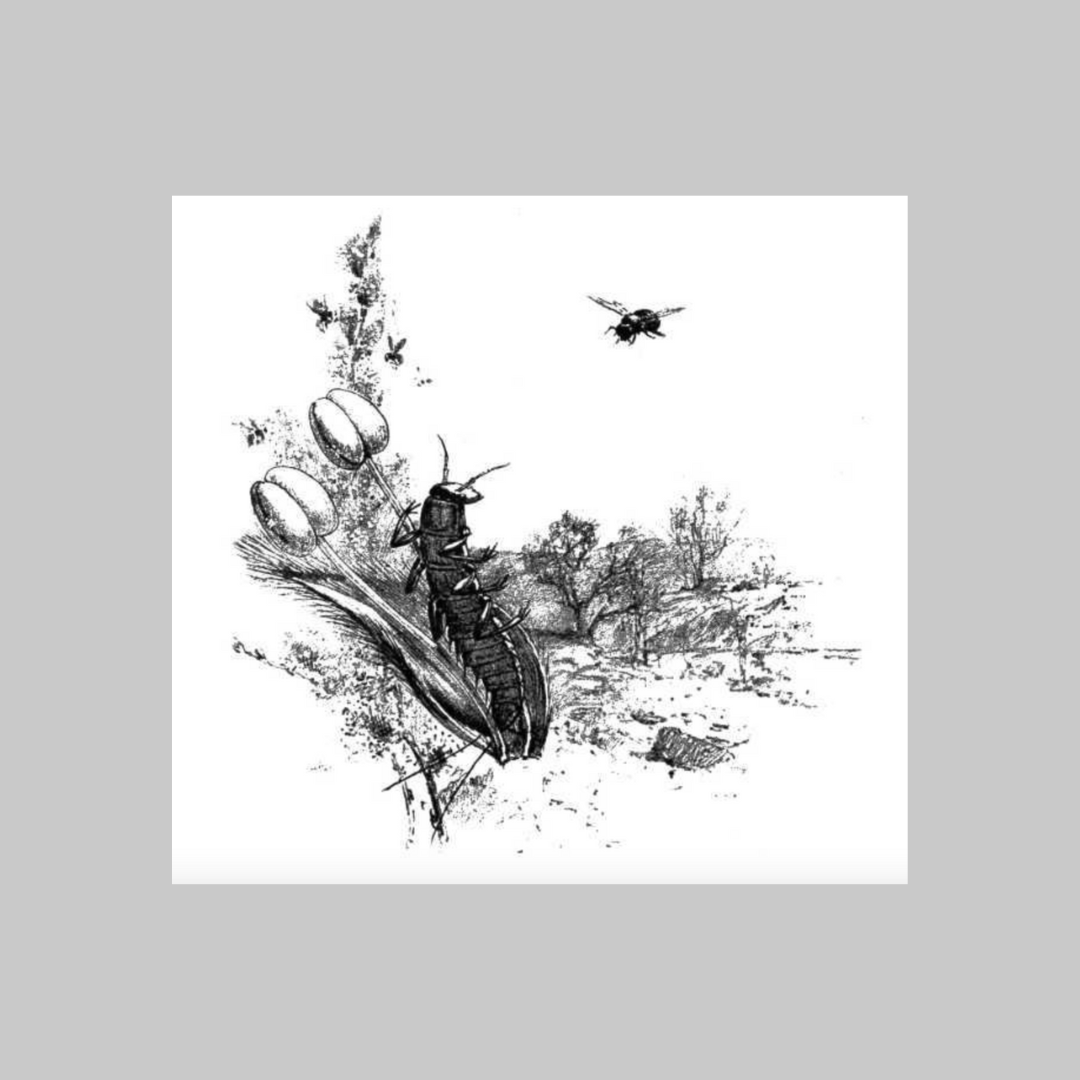

The Story of The Floundering Beetle

AMONG my somewhat numerous correspondence from young people, I recall several wondering inquiries about a certain fat, floundering “beetle,” as “blue as indigo”; and when we consider how many other observing youngsters, including youngsters of larger growth, have looked upon this uncouth shape in the path, lawn, or pasture, will speculate as to its life history, it is perhaps well to make this floundering blue beetle better acquainted with his unappreciative neighbors.

What are the lazy blue insects doing down there in the grass, for there are usually a small family of them. With the exception of their tinselled indigo-blue coat, there is certainly very little to admire in them. But what they lack in beauty they make up for in other ways. There are many of their handsomer cousins whose history is not half as interesting as that of this poor beetle that we tread upon in the grass. His neighbor insect, the tiger-beetle, running hither and thither with legs of wonderful speed, and with the agility of a fly on the wing, readily escapes our approach; but this clumsy, helpless blue beetle must needs plead for mercy by his color alone, because he has no means to avert our crushing step. A little girl who met me on the country road recently summed up the characteristics of the blue beetle pretty well.

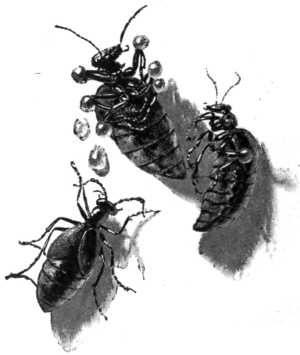

The portrait was unmistakable. “I’ve got a funny blue bug at home in a box that I want to show you,” said she; “he’s blue and awful fat, and hasn’t got any wings, but when you touch him, he just turns over on his back, and trembles his toes and leaks big yellow drops out of his elbows.” I have shown her beetle—three views of him, in fact—about the natural size, one of them on his back and “leaking” at his elbows, for such is the infallible habit of the insect when disturbed—a trick which has also given him the name of the “oil beetle.” He is also known as the indigo beetle.

But of what use can such a queer beetle be to himself or any one else—a beetle that is not only without wings, but is so fat and floundering that he can hardly lift his unwieldy body from the ground, and which, upon being surprised, can only “play possum,” and exude great drops of oil (?) upon our palm as we examine him?

But as he pours the vials of his wrath upon us he would doubtless fain have us understand that he was not always thus unable to take care of himself, that he was not always the clumsy, crawling creature that he now is. As he lies there on his back, the yellow, oily globules of surplus “elbow grease” swelling larger and larger at his leaky elbows, and one by one falling on the paper beneath him, we may almost fancy the monologue which might be going on in that blue head of his.

“Yes, I am indeed a clumsy creature,” he might be saying, as he stares upward into our faces with fixed indigo eyes, “and my cumbersome body is a burden. But I was not always what you now see. Ah, you should have seen me as a baby! Was there ever such a lively, acrobatic, venturesome, plucky baby as I, even when I was a day old? Shall I tell you some of my feats? Everybody knows me as I am now; but I have taken care that few shall learn my earlier history. It takes a sharp eye to follow my pranks of babyhood, and no one has been smart enough to do it yet, but I will at least let you into the secret of my life as far as it has been found out. I am little over a year old. I was born under a stone in a meadow last April, when I crept out of a golden-yellow case so small that you could hardly see it. I believe your books say I was about a sixteenth of an inch long at that time. Ah! when I think of what I was and what I could do then, and look at what I am now, I sometimes wonder whether that lively babyhood of mine has not all been a mocking dream.

“Do you wonder that I am as blue as indigo, and am occasionally forced to resort to my oil-tank to still the troubled waters of my later experience? Well, as I was saying (pardon this fresh display of tears), when I crept out of that filmy egg-sac I was just ready for anything, and spoiling for adventure. I found myself with a slender, agile body of thirteen joints, and three pairs of the sprightliest, spider-like legs you ever saw, each tipped with three little sharp claws. Now I knew that these long legs and claws were not given to me at this early babyhood for nothing, so I looked about for something to try them on. I had not a great while to wait, for as I crept along through the grass roots beneath the edge of the stone, I heard a welcome sound, which is music to all babies of my kind. I remembered having heard the same music in my dreams while inside the little yellow case, but now it seemed louder than ever, and in another minute I was almost blown off my feet by the breeze which the noise made, and a great black, hairy giant, as big as a house, pounced down just outside the stone. He had a great black head, and six enormous legs as big round as trees. Think how a bumblebee would look to a wee baby not half as big as a hyphen in one of your books! Did I run when I saw him coming? Not a bit of it. I just waited until he came close to me, and then I jumped on his back, and put those eighteen little claws of mine to good use as I crept over his great spiny body, and finally found a snug resting-place beneath it. And then I waited, clinging tightly with my clutching feet. In another moment I had begun to take my first outing; and did ever baby have such a ride, and to such music! After the bumblebee had remained under the stone a little while he turned and went out again. No sooner did he get to the edge than he spread his great buzzing wings, and away we went over the world, higher and higher, miles high, over big oceans and mountains. I could see them all beneath me as I clung to the underside of the bee. I believe I must finally have got dizzy and faint, for I remember at last finding myself at rest in a queer thicket of greenish poles with big yellow balls at the top of them, and great giant leaves fringed with long, glistening hairs. They told me afterwards it was a willow blossom.

“It seemed a very good place to rest, so I dropped off from my bee and remained. Everywhere about me, as I looked, the air was yellow with these blossoms, and full of the wing-music of the bees. But, as I have said, I was a restless baby, and having had a taste of travel I soon tired of this idle life, and began to get ready for another ride. My chance soon came. This time it was a honey-bee. She alighted in the flower next to mine, but I quietly piled over and clutched upon her leg, and was soon snugly tucked away under her body, with my flat head between its segments. And now for the first time I began to feel hungry; and what was more natural than to take a bite from the tender flesh of this bee, so easily available? I did it, and liked it so well that I adopted this bee for my mother for quite a long while, taking many, many long rides every day, and always coming back to the prettiest little house on a bench under the trees. This was a sort of bee hotel, with many hundreds of guests. It was all partitioned off inside into little six-sided rooms, and the walls were so thin that you could see through them. Indeed, I soon came to like this little home so well that one morning I decided that I would not leave it again. I had begun to get tired of my roving life. I saw a lot of little white fat babies tucked away in some of these little rooms, and this very bee which I had adopted as my mother was engaged in bringing food to some of these babies and sealing them up in their nests. This was enough for me. I concluded to bring my roving habit to a close, and become a bee baby in truth; so watching for my opportunity, I loosened my clutch upon the mother bee, and dropped into one of the little rooms.

“Then I became sleepy, and can tell you nothing more than that when I woke up I didn’t know who or what I was. My six spider legs had gone, and I had a half-dozen little short feet instead; and instead of the sprightly ideas of my baby days, the thought of such a thing as even moving was a bore. But I was hungrier than ever, and the first thing I did was to fall upon another fat youngster who disputed the room with me, and make short work of him. That was breakfast.” When dinner-time came, I found it right at my mouth. That busy mother of mine had fully supplied my wants, and packed my room full to the ceiling with the most delicious, fragrant bread of flowers made of pollen and honey.

“Oh, those were good old times, with all I wanted to eat all the time, and everything I ate turning to appetite! Too soon, too soon I found myself getting drowsy again, and, I can only remember awakening from a queer dream, to find even my six tiny legs gone, and, what is worse, my mouth also. While wondering and hoping that this was but a troubled vision, I was plunged into sleep again, and dreamed that I was locked up in a mummy-case for over a week. And now comes the end, the cycle of my story. From this nightmare mummy-case I finally awoke—awoke, and emerged as you now see me. Do you wonder that I have had the blues ever since at the memory of those honeyed days, now forever fled? Instead of sporting aloft in airy skyward flights, I am now a miserable groundling. Instead of sweet, fragrant bread of flowers, I am now forced to break my fast on acrid buttercup leaves. But I shall live again, with joys several hundred times multiplied, live again in my children, for whose jolly time in the autumn I shall soon lay my plans—golden promises—here in the ground beneath the buttercup leaves, close to a burrow where lives a burly bumblebee.

“But I have not told you all of my history, and will leave you to fill in the blank spaces, even as some of the scientists have to do.”

But this light was of a greenish, ghostly hue, and perfectly motionless, and had withal a certain weird, uncanny glare, which belongs alone to fox-fire. It was impossible to locate its distance from us. It might as easily be one rod as five. I concluded to investigate its source, and, groping my way through the dewy bushes, soon confronted it. It seemed to glow with added brilliancy as I approached it, and as I stood face to face within a few inches of it no vestige of material surface appeared to sustain it; it seemed hanging motionless in mid-air. I reached out my hand, which momentarily intervened like a black silhouette against the glow, with which it soon came in contact. Upon further investigation, this proved to be the contact of a mere prosaic fence-post, which, for some mysterious reason, had been singled out for glorification among the ten thousand others of its neighbors and transformed into a pillar of fire. The post was about six inches in diameter, its summit an unbroken mass of light, which extended in more or less broken patches below for a distance of six feet, thus suggesting the effect of the rippling elongated reflection of a lantern in water noticed by my companion, and which would doubtless have been so accepted by the average passing observer without further thought.

The most luminous upper portions were free from bark, the exposed patches of wood below being equally brilliant. Clutching at the more available part of the post, I was enabled to sink my fingers deep into its decayed fibre, and succeeded in tearing off a long fragment. The outer surface of this particular piece had been covered with bark and not especially brilliant, but the cavity of yielding moist fibre thus exposed, as well as the inner surface of the dislodged piece, poured forth a perfect flood of greenish light, indicating that the damp uncanny fire extended to the very core of the post, which was saturated with the phosphorescent essence. I laid this and other fragments in the back of the carriage, where its glare met our eyes whenever we turned to look upon it

Taking it beneath the lamp-light upon our return home, it resolved itself into a very ordinary piece of yellowish rotten wood. In a more shaded corner of the room it appeared as though white-washed, and upon taking it into a closet or out into the night again its flame gradually rekindled, as though feeding upon the darkness, until it appeared precisely as when we found it.

By enclosing the specimen in a tin box with moist moss I was enabled to prolong the effulgence until the next evening, but it had entirely disappeared by the following night, at which time its original haunt, the post, was also doubtless lost in the darkness. A week later I again passed its neighborhood in the late hours without the slightest hint of its presence.

This is the mysterious “fox-fire” or “ghost-fire” which has so imposed upon the imaginations of credulous country folk the world over, doubtless a conspicuous factor in many a harrowing tale in the legendary or traditional lore of spooks and goblins.

I remember the breathless interest with which as a boy I listened to the weird story, whose scene was located not far from my native town, of a ghostly light that flickered about the eaves of a certain old ruin of a house in the neighborhood, and also above the well close by in the weedy waste of the former door-yard.

The light was seen by many for several consecutive nights. It fairly glowed into a halo up from the wooden curb which surmounted the well, where it was viewed at a safe distance with bated breath by a curious crowd of villagers, not one of whom would have dared to steal up and surprise the innocent spook in its haunt—doubtless a mass of fox-fire which had found its brief, congenial home in the decaying boards within the tottering well-curb. Of course the house was “haunted” for evermore, and rustic tradition for a whole generation was rich in fabulous tales of the “haunted well,” and there was serious talk of unearthing the nameless mystery which lay at the bottom of it.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.