MOONLIGHT.

“The light of the moon and the changes of the moon were probably the first phenomena which led men to study the motions of the heavenly bodies. In our times, when most men live where artificial illumination is used at night, we can scarcely appreciate the full value of moonlight to men who cannot obtain artificial light. …The tiller of the soil might fare tolerably well without nocturnal light, though even he,—as indeed the familiar designation of the harvest-moon shows us,—finds special value, sometimes, in moonlight.

“But to the shepherd moonlight and its changes must have been of extreme importance as he watched his herds and flocks by night. We can understand how carefully he would note the change from the new moon to the time when throughout the whole night, or at least of the darkest hours, the full moon illuminated the hills and valleys over which his watch extended, and thence to the time when the sickle of the fast waning moon shone but for a short time before the rising of the sun.

“To him [the shepherd], naturally, the lunar month, and its subdivision, the week, would be the chief measure of time. He would observe—or rather he could not help observing—the passage of the moon around the zodiacal band, some twenty moon-breadths wide, which is the lunar roadway among the stars. These would be the first purely astronomical observations made by man; so that we learn without surprise that before the present division of the zodiac was adopted the old Chaldean astronomers (as well as the Indian, Persian, Egyptian, and Chinese astronomers, who still follow the practice) divided the zodiac into 28 lunar mansions, each mansion corresponding nearly to one day’s motion of the moon among the stars.

“It is easy to understand how the first rough observations of moonlight and its changes taught men the true nature of the moon, as an opaque globe circling round the earth, and borrowing her light from the sun. They perceived, first, that the moon was only full when she was opposite the sun, shining at her highest in the south at midnight when the sun was at his lowest beneath the northern horizon. Before the time of full moon, they saw that more or less of the moon’s disc was illuminated as he was nearer or farther from the position opposite the sun, the illuminated side being towards the west—that is, towards the sun; while after full moon the same law was perceived in the amount of light, the illuminated side being still towards the sun, that is, towards the east. They could not fail to observe the horned moon sometimes in the daytime, with her horns turned directly from the sun, and showing as plainly, by her aspect, whence her light was derived, as does any terrestrial ball lit up either by a lamp or by the sun.” Proctor, Richard A. Flowers of the Sky.

In Deuteronomy 33:14, the Bible says that blessed are the things that grow in the sun:“

“Blessed of the Lord is his land,

With the precious things of heaven, with the dew,

And the deep lying beneath,

14 With the precious fruits of the sun,

With the precious produce of the months,

15 With the best things of the ancient mountains,

With the precious things of the everlasting hills,

16 With the precious things of the earth and its fullness…” Deuteronomy 33: 13-16

Unfortunately, that scripture does not say that many things also grow and blossom by the light of the moon.

Planting by the Moon

“… although mankind in all ages have regarded, and even worshipped, the Sun as being the supreme and ruling luminary, from whose glorious life-giving rays, vegetation of all kinds drew its very existence… the growth and decay of plants were [also] associated intimately with the waxing and waning of the Moon. We have seen how the plant kingdom was parcelled out by the astrologers, and consigned to the care of different Planets; but, despite this, the Moon was held to have a singular and predominant influence over vegetation, and it was supposed that there existed a sympathy between growing and declining nature and the Moon’s wax and wane. …

“As an illustration of the predominance given to the Moon over the other planets in matters pertaining to plant culture, it is worth noticing that, although Culpeper, in his ‘Herbal,’ places the Apple under Venus, yet the Devonshire farmers have from time immemorial made it a rule to gather their Apples for storing at the wane of the Moon; the reason being that, during the Moon’s increase, it is thought that the Apples are full, and will not therefore keep.” Folkard

The eight Moon phases:

🌑 New: We cannot see the Moon when it is a new moon.

🌒 Waxing Crescent: In the Northern Hemisphere, we see the waxing crescent phase as a thin crescent of light on the right.

🌓 First Quarter: We see the first quarter phase as a half moon.

🌔 Waxing Gibbous: The waxing gibbous phase is between a half moon and full moon. Waxing means it is getting bigger.

🌕 Full: We can see the Moon completely illuminated during full moons.

🌖 Waning Gibbous: The waning gibbous phase is between a full moon and a half moon. Waning means it is getting smaller.

🌗 Third Quarter: We see the third quarter moon as a half moon, too. It is the opposite half as illuminated in the first quarter moon.

🌘 Waning Crescent: In the Northern Hemisphere, we see the waning crescent phase as a thin crescent of light on the left.

“The Moon displays these eight phases one after the other as it moves through its cycle each month. It takes about 27.3 days for the Moon to orbit Earth. However, because of how sunlight hits the Moon, it takes about 29.5 days to go from one new moon to the next new moon.” Space Place – NASA

“It is said that if timber be felled when the Moon is on the increase, it will decay; and that it should always be cut when the Moon is on the wane. No reason can be assigned for this; yet the belief is common in many countries, and what is still more strange, professional woodcutters, whose occupation is to fell timber, aver, as the actual result of their observation, that the belief is well founded. It was formerly interwoven in the Forest Code of France, and, unless expunged by recent alterations, is so still. [This book was published in 1888.] The same opinion obtains in the German forests, and is said to be held in those of Brazil and Yucatan. The theory given to account for this supposed fact is, that as the Moon grows, the sap rises, and the wood is therefore less dense than when the Moon is waning, because at that time the sap declines. The belief in the Moon’s influence as regards timber extends to vegetables, and was at one time universal in England, although, at the present day, the theory is less generally entertained in our country than abroad, where they act upon the maxim that root crops should be planted when the Moon is decreasing, and plants such as Beans, Peas, and others, which bear the crops on their branches, between new and full Moon. Throughout Germany, the rule is that Rye should be sown as the Moon waxes; but Barley, Wheat, and Peas, when it wanes.

“The wax and wane of the belief in lunar influence on plant-life among our own countrymen may be readily traced by reference to old books on husbandry and gardening.

In ‘The Boke of Husbandry,’ by Mayster Fitzherbarde, published in 1523, we read with respect to the sowing of Peas, that “moste generally to begyn sone after Candelmasse is good season, so that they be sowen ere the begynnynge of Marche, or sone upon. And specially let them be sowen in the olde of the Mone. For the opinion of old husbandes is, that they shoulde be better codde, and sooner be rype.”

Tusser, in his ‘Five Hundred Points of Husbandry,’ published in 1562, says, in his quaint verse—

“In ‘The Countryman’s Recreation’ (1640) the author fully recognises the obligation of gardeners to study the Moon in all their principal operations. Says he: “From the first day of the new Moone unto the xiii. day thereof is good for to plant, or graffe, or sow, and for great need some doe take unto the xvii. or xviii. day thereof, and not after, neither graffe nor sow, but as is afore-mentioned, a day or two afore the change, the best signes are Taurus, Virgo, or Capricorne.” And as regards the treatment of fruit trees, he tells us that “trees which come of Nuttes” should be set in the Autumn “in the change or increase of the Moone;” certain grafting manipulations are to be executed “in the increase of the Moone and not lightly after;” fruit, if it is desired of good colour and untouched by frost, ought to be gathered “when the time is faire and dry, and the Moone in her decreasing;” whilst “if ye will cut or gather Grapes, to have them good, and to have good wine thereof, ye shall cut them in the full, or soone after the full, of the Moone, when she is in Cancer, in Leo, in Scorpio, and in Aquarius, the Moone being on the waine and under the earth.”

“In ‘The Expert Gardener’ (1640)—a work stated to be “faithfully collected out of sundry Dutch and French authors”—a chapter is entirely devoted to the times and seasons which should be selected “to sow and replant all manner of seeds,” with special reference to the phases of the Moon. As showing how very general must have been the belief in the influence of the Moon on vegetation at that time, the following extract is given:—

A short Instruction very profitable and necessary for all those that delight in Gardening, to know the Times and Seasons when it is good to sow and replant all manner of Seeds.

Cabbages must be sowne in February, March, or April, at the waning of the Moone, and replanted also in the decrease thereof.

Cabbage Lettuce, in February, March, or July, in an old Moone.

Onions and Leeks must be sowne in February or March, at the waning of the Moone.

Beets must be sowne in February or March, in a full Moone.

Coleworts white and greene in February, or March, in an old Moone, it is good to replant them.

Parsneps must be sowne in February, April, or June, also in an old Moone.

Radish must be sowne in February, March, or June, in a new Moone.

Pompions must be sowne in February, March, or June, also in a new Moone.

Cucumbers and Mellons must be sowne in February, March, or June, in an old Moone.

Spinage must be sowne in February or March, in an old Moone.

Parsley must be sowne in February or March, in a full Moone.

Fennel and Annisseed must be sowne in February or March, in a full Moone.

White Cycory must be sowne in February, March, July, or August, in a full Moone.

Carduus Benedictus must be sowne in February, March, or May, when the Moone is old.

Basil must be sowne in March, when the Moone is old.

Purslane must be sowne in February or March, in a new Moone.

Margeram, Violets, and Time must be sowne in February, March, or April, in a new Moone.

Floure-gentle, Rosemary, and Lavender, must be sowne in February or April, in a new Moone.

Rocket and Garden Cresses must be sowne in February, in a new Moone.

Savell must be sowne in February or March, in a new Moone.

Saffron must be sowne in March, when the Moone is old.

Coriander and Borage must be sowne in February or March, in a new Moone.

Hartshorne and Samphire must be sowne in February, March, or April, when the Moone is old.

Gilly-floures, Harts-ease, and Wall-floures, must be sowne in March or April, when the Moone is old.

Cardons and Artochokes must be sowne in April or March, when the Moone is old.

Chickweed must be sowne in February or March, in the full of the Moone.

Burnet must be sowne in February or March, when the Moone is old.

Double Marigolds must be sowne in February or March, in a new Moone.

Isop and Savorie must be sowne in March when the Moone is old.

White Poppey must be sowne in February or March, in a new Moone.

Palma Christi must be sowne in February, in a new Moone.

Sparages and Sperage is to be sowne in February, when the Moone is old.

Larks-foot must be sowne in February, when the Moone is old.

Note that at all times and seasons, Lettuce, Raddish, Spinage and Parsneps may be sowne.

Note, also, from cold are to be kept Coleworts, Cabbage, Lettuce, Basill, Cardons, Artochokes, and Colefloures.

In ‘The English Gardener’ (1683) and ‘The Dutch Gardener’ (1703) many instructions are given as to the manner of treating plants with special regard to the phases of the Moon; and Rapin, in his poem on Gardens, has the following lines:—

John Evelyn, in his ‘Sylva, or a Discourse on Forest Trees,’ first published in 1662, remarks on the attention paid by woodmen to the Moon’s influence on trees. He says: “Then for the age of the Moon, it has religiously been observed; and that Diana’s presidency in sylvis was not so much celebrated to credit the fictions of the poets, as for the dominion of that moist planet and her influence over timber. For my part, I am not so much inclined to these criticisms, that I should altogether govern a felling at the pleasure of this mutable lady; however, there is doubtless some regard to be had—

‘Nor is’t in vain signs’ fall and rise to note.’

The old rules are these: Fell in the decrease, or four days after the conjunction of the two great luminaries; sowe the last quarter of it; or (as Pliny) in the very article of the change, if possible; which hapning (saith he) in the last day of the Winter solstice, that timber will prove immortal. At least should it be from the twentieth to the thirtieth day, according to Columella; Cato, four days after the full, as far better for the growth; nay, Oak in the Summer: but all vimineous trees, silente lunâ, such as Sallows, Birch, Poplar, &c. Vegetius, for ship timber, from the fifteenth to the twenty-fifth, the Moon as before.” In his ‘French Gardener,’ a translation from the French, Evelyn makes a few allusions to the Moon’s influence on gardening and grafting operations, and in his Kalendarium Hortense we find him acknowledging its supremacy more than once; but he had doubtless begun to lose faith in the scrupulous directions bequeathed by the Romans. In his introduction to the ‘Kalendar’ he says:—“We are yet far from imposing (by any thing we have here alledged concerning these menstrual periods) those nice and hypercritical punctillos which some astrologers, and such as pursue these rules, seem to oblige our gard’ners to; as if forsooth all were lost, and our pains to no purpose, unless the sowing and the planting, the cutting and the pruning, were performed in such and such an exact minute of the Moon: In hac autem ruris disciplina non desideratur ejusmodi scrupulositas. [Columella]. There are indeed some certain seasons and suspecta tempora, which the prudent gard’ner ought carefully (as much as in him lies) to prevent: but as to the rest, let it suffice that he diligently follow the observations which (by great industry) we have collected together, and here present him.”

The opinion of John Evelyn, thus expressed, doubtless shook the faith of gardeners in the efficacy of lunar influence on plants, and, as a rule, we find no mention of the Moon in the instructions contained in the gardening books published after his death. It is true that Charles Evelyn, in ‘The Pleasure and Profit of Gardening Improved’ (1717) directs that Stock Gilliflower seeds should be sown at the full of the Moon in April, and makes several other references to the influence of the Moon on these plants; but this is an exception to the general rule, and in ‘The Retired Gardener,’ a translation from the French of Louis Liger, printed in 1717, the ancient belief in the Moon’s supremacy in the plant kingdom received its death-blow. The work referred to was published under the direction of London and Wise, Court Nurserymen to Queen Anne, and in the first portion of it, which is arranged in the form of a conversation between a gentleman and his gardener, occurs the following passage:—

Gent.—“I have heard several old gardeners say that vigorous trees ought to be prun’d in the Wane, and those that are more sparing of their shoots in the Increase. Their reason is, that the pruning by no means promotes the fruit if it be not done in the Wane. They add that the reason why some trees are so long before they bear fruit is, because they were planted or grafted either in the Increase or Full of the Moon.”

Gard.—“Most of the old gardeners were of that opinion, and there are some who continue still to be misled by the same error. But ’tis certain that they bear no ground for such an imagination, as I have observ’d, having succeeded in my gardening without such a superstitious observation of the Moon. However, I don’t urge this upon my own authority, but refer my self to M. de la Quintinie, who deserves more to be believed than my self. These are his words:—

‘I solemnly declare [saith he] that after a diligent observation of the Moon’s changes for thirty years together, and an enquiry whether they had any influence on gardening, the affirmation of which has been so long established among us, I perceiv’d that it was no weightier than old wives’ tales, and that it has been advanc’d by unexperienc’d gardeners.’

“And a little after: ‘I have therefore follow’d what appear’d most reasonable, and rejected what was otherwise. In short, graft in what time of the Moon you please, if your graft be good, and grafted in a proper stock, provided you do it like an artist, you will be sure to succeed…. In the same manner [continues he] sow what sorts of grain you please, and plant as you please, in any Quarter of the Moon, I’ll answer for your success; the first and last day of the Moon being equally favourable.’ This is the opinion of a man who must be allow’d to have been the most experienc’d in this age.”

Plants of the Moon.

The Germans call Mondveilchen (Violet of the Moon), the Lunaria annua, the Leucoion, also known as the Flower of the Cow, that is to say, of the cow Io, one of the names of the Moon. The old classic legend relates that this daughter of Inachus, because she was beloved by Jupiter, fell under the jealous displeasure of Juno, and was much persecuted by her. Jupiter therefore changed his beautiful mistress into the cow Io, and at his request, Tellus (the Earth) caused a certain herb (Salutaris, the herb of Isis) to spring up, in order to provide for the metamorphosed nymph suitable nourishment. In the Vedic writings, the Moon is represented as slaying monsters and serpents, and it is curious to note that the Moonwort (Lunaria), Southernwood (Artemisia), and Selenite (from Selene, a name of the Moon), are all supposed to have the power of repelling serpents. Plutarch, in his work on rivers, tells us that near the river Trachea grew a herb called Selenite, from the foliage of which trickled a frothy liquid with which the herdsmen anointed their feet in the Spring in order to render them impervious to the bites of serpents. This foam, says De Gubernatis, reminds one of the dew which is found in the morning sprinkled over herbs and plants, and which the ancient Greeks regarded as a gift of the nymphs who accompanied the goddess Artemis, or Diana, the lunar deity.

Numerous Indian plants are named after the Moon, the principal being the Cardamine; the Cocculus cordifolius (the Moon’s Laughter); a species of Solanum called the Flower of the Moon; the Asclepias acida, the Somalatâ, the plant that produces Soma; Sandal-wood (beloved of the Moon); Camphor (named after the Moon); the Convolvulus Turpethum, called the Half-Moon; and many other plants named after Soma, a lunar synonym.

In a Hindu poem, the Moon is called the fructifier of vegetation and the guardian of the celestial ambrosia, and it is not surprising therefore to find that in India the mystic Moon-tree, the Soma, the tree which produces the divine and immortalising ambrosia is worshipped as the lunar god. Soma, the moon-god, produces the revivifying dew of the early morn; Soma, the Moon-tree, the exhilarating ambrosia. The Moon is cold and humid: it is from her the plants receive their sap, says Prof. De Gubernatis, “and thanks to the Moon that they multiply, and that vegetation prospers. There is nothing very wonderful, therefore, if the movements of the Moon preside in a general way over agricultural operations, and if it exercises a special influence on the health and accouchements of women, who are said to represent Water, the humid element. The Roman goddess Lucina (the Moon) presided over accouchements, and had under her care the Dittany and the Mugwort [or Motherwort] (Artemisia, from Artemis, the lunar goddess), considered, like the Vedic Soma, to be the queen or mother of the herbs.”

Thus Macer says of it:—

This influence of the Moon over the female portion of the human race has led to a class of plants being associated either directly with the luminary or with the goddesses who were formerly thought to impersonate or embody it. Thus we find the Chrysanthemum leucanthemum named the Moon Daisy, because its shape resembles the pictures of a full moon, the type of a class of plants which Dr. Prior points out, “on the Doctrine of Signatures, were exhibited in uterine complaints, and dedicated in pagan times to the goddess of the Moon and regulator of monthly periods, Artemis, whom Horsley (on Hosea ix., 10) would identify with Isis, the goddess of the Egyptians, with Juno Lucina, and with Eileithuia, a deity who had special charge over the functions of women—an office in Roman Catholic mythology assigned to Mary Magdalene and Margaret.” The Costmary, or Maudeline-wort (Balsamita vulgaris); the Maghet, or May-weed (Pyrethrum Parthenium); the Mather, or Maydweed (Anthemis Cotula); the Daisy, or Marguerite (Bellis perennis); the Achillea Matricaria, &c., are all plants which come under the category of lunar herbs in their connection with feminine complaints.

Folkard, Richard. Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics.

This scenario plays out in seeking to understand whether the Ancient Egyptian god of the Sun – Ra was actually more loved thaN the Ancient Egytian god Osiris, who is often associated with the Moon. Most people would quickly say that Ra was the most favored god among the Ancient Egyptians, but others might disagree:

Ra

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Ra-Horakhty and Ra are both depicted in the same way with the head of a falcon and the body of a human. Ra-Horakhty © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- A god of the sun, associated with light, warmth and growth.

- Frequently depicted with the head of a falcon and the body of a human.

- Often considered to be the first king, ruling initially over humans and gods on earth and then later in the heavens.

- Believed to have the power to control the sky and the weather, as well as life and death.

- His cult and main temple were located in a town called Heliopolis, which means ‘City of the Sun’ in Greek. British Museum

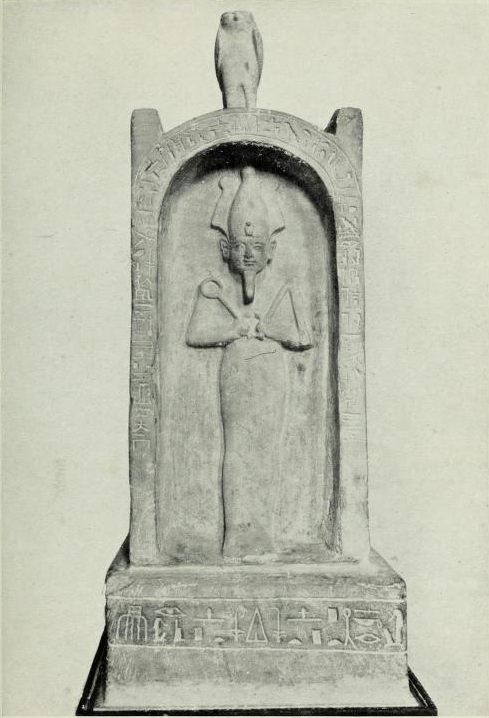

Osiris

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Osiris depicted as a mummified man with green skin, holding a crook and flail. Osiris © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- God of the afterlife and fertility (new life).

- Married to Isis and father of Horus.

- Murdered by his brother Seth, but brought back to life by Isis.

- Usually depicted as a mummified man with green or black skin, holding a crook and flail (in ancient Egypt a flail is a rod with three beaded strands attached to the top).

- Ancient Egyptians believed that he judged the souls of the dead and decided whether they were worthy of entering the afterlife.

- He was linked with the annual flooding of the Nile river, which brought new plant life – just like he was brought back to life.

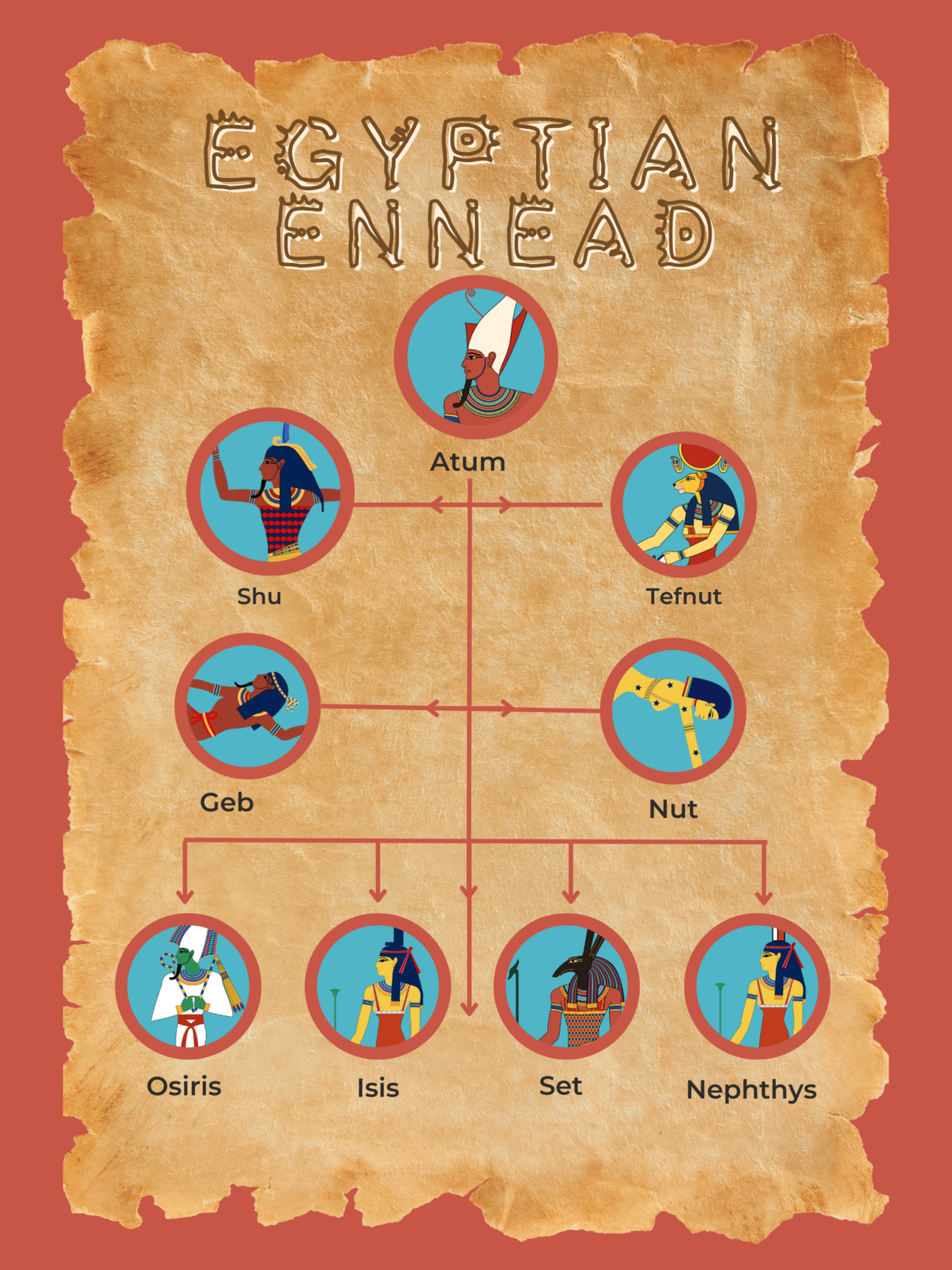

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

THE CULT OF OSIRIS

Osiris

“One of the principal figures in the Egyptian pantheon, and one whose elements it is most difficult to disentangle, is Osiris, or As-ar. The oldest and most simple form of the name is expressed by two hieroglyphics representing a throne and an eye. These, however, cast but little light on the meaning of the name. … In dynastic times Osiris was regarded as god of the dead and the under-world. Indeed, he occupied the same position in that sphere as Ra did in the land of the living. We must also recollect that the realm of the under-world was the realm of night.

“The origins of Osiris are extremely obscure. We cannot glean from the texts when or where he first began to be worshipped, but that his cult is greatly more ancient than any text is certain. The earliest dynastic centres of his worship were Abydos and Mendes. …Osiris dwells peaceably in the underworld with the justified, judging the souls of the departed as they appear before him. This paradise was known as Aaru, which, it is important to note, although situated in the under-world, was originally thought to be in the sky.

…

“Brugsch and Sir Gaston Maspero both regarded him as a water-god,[1] and thought that he represented the creative and nutritive powers of the Nile stream in general, and of the inundation in particular. This theory is agreed to by Dr. Budge, but if Osiris is a god of the Nile alone, why import him from the Libyan desert, which boasts of no rivers? River-gods do not as a rule emanate from regions of sand. Before proceeding further it will be well to relate the myth of Osiris.” Folkard

First, allow me to point out that Osiris was one of the Egyptian Ennead [the first 9 deities in Ancient Egyptian Mythology. Ra did not come along until later.

The following myth also talks about Nut, who was also one of the Ennead:

Nut

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Nut depicted as a woman with a starry body, arching over the Earth.”

- A goddess who represented the sky.

- Usually depicted as a woman with a starry body, arching over the Earth.

- Married to the god of the earth, Geb, and together they had four children: Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys.

- According to Egyptian mythology, she swallowed the sun every night and gave birth to it every morning.

- Egyptians believed that she protected and watched over the souls of the dead – they would travel through her body on their way to the afterlife, like the sun every night.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

Disclaimer: Egyptian Myths Vary. In the following myth, Nut was married to Ra, but she loved Geb–god of the earth:

Geb

Image Credit: British Museum

“Geb depicted as a man lying on his back, with his arms and legs stretched out to represent the land.”

- God of the earth and fertility (new life).

- Often depicted as a man lying on his back, with his arms and legs stretched out to represent the land.

- Married to Nut, goddess of the sky.

- Father of many other gods and goddesses, including Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys.

- The ancient Egyptians believed that he helped to bring about a good harvest.

- Also associated with the idea of stability and balance, as he was believed to help keep the earth firmly in place and prevent chaos and disorder.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

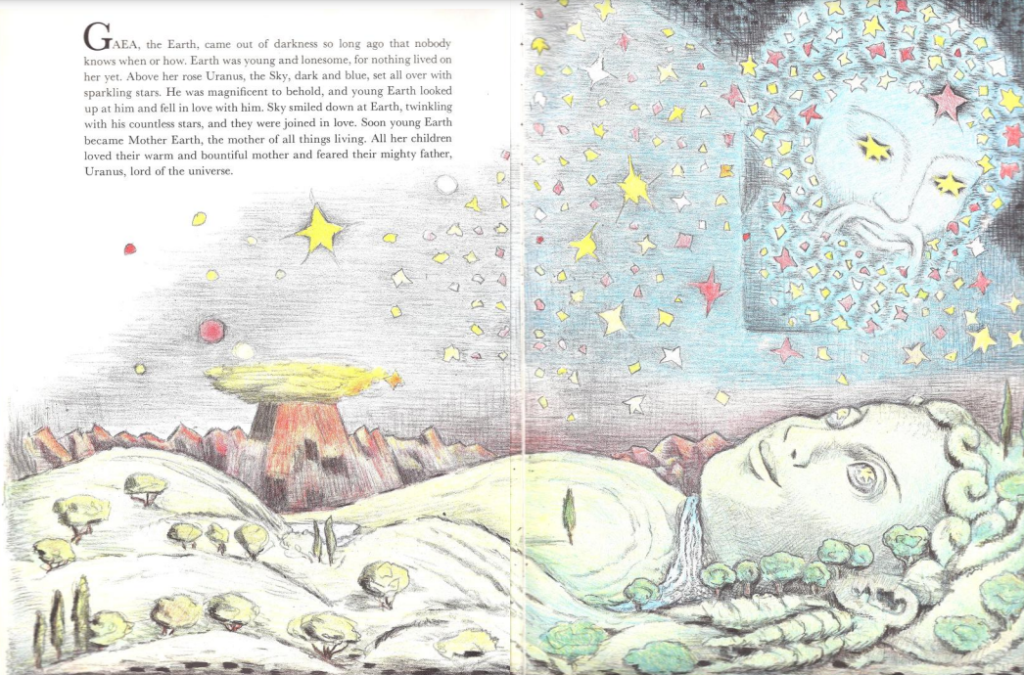

Before I move on, allow me to digress for a moment and say that the interplay between Earth and Sky is part of many creation stories:

In Ancient Greek Mythology, Uranus was the Primordial god of the Sky, and in illustrations, he is often placed in a dome-like position hovering over Gaea.

D’Aulaire, Ingri, and Edgar Parin D’Aulaire. D’Aulaires Book of Greek Myths. New York, United States, Penguin Random House, 1992.

Uranus was like the Heavens comparable to what is mentioned in Genesis 1:1, and Gaea was the Earth.

As we continue this discussion, consider that in any photograph of a natural horizon, the sky is above the earth or the sea. In many cases, mythology is a result of the stories that people tell themselves, as they seek to understand why things are–as they are.

An Ancient Egyptian Creation Myth

“Plutarch is our principal authority for the legend of Osiris. A complete version of the tale is not to be found in Egyptian texts, though these confirm the accounts given by the Greek writers. The following is a brief account of the myth as it is related in Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride:

“Rhea (the Egyptian Nut, the sky-goddess) was the [pg 65] wife of Helios (Ra). She was, however, beloved by Kronos (Geb), whose affection she returned. When Ra discovered his wife’s infidelity he was wrathful indeed, and pronounced a curse upon her, saying that her child should not be born in any month or in any year. Now the curse of Ra the mighty could not be turned aside, for Ra was the chief of all the gods. In her distress Nut called upon the god Thoth (the Greek Hermes), who also loved her.” Folkard

Image Credit: British Museum.

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Thoth depicted with the head of an ibis bird and the body of a human. Thoth © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

Thoth

- God of wisdom, writing and knowledge, as well as a moon god.

- Often depicted with the head of an ibis bird and the body of a human, but he was sometimes depicted as a baboon.

- Frequently associated with scribes and scholars, as he was believed to have invented hieroglyphs, the ancient Egyptian writing system.

- Also believed to have the power to heal illnesses and injuries – he was considered a great magician.

“Thoth knew that the curse of Ra must be fulfilled, yet by a very cunning stratagem he found a way out of the difficulty. He went to Silene, the moon-goddess, whose light rivalled that of the sun himself, and challenged her[2] to a game of tables. The stakes on both sides were high, but Silene staked some of her light, the seventieth part of each of her illuminations, and lost. Thus it came about that her light wanes and dwindles at certain periods, so that she is no longer the rival of the sun. From the light which he had won from the moon-goddess Thoth made five days which he added to the year (at that time consisting of three hundred and sixty days) in such wise that they belonged neither to the preceding nor to the following year, nor to any month. On these five days Nut was delivered of her five children. Osiris was born on the first day, Horus on the second, Set on the third, Isis on the fourth, and Nephthys on the fifth.[3] On the birth of Osiris a loud voice was heard throughout all the world saying, “The lord of all the earth is born!” A slightly different tradition relates that a certain man named Pamyles, carrying water from the temple of Ra at Thebes, heard[Pg 66] a voice commanding him to proclaim the birth of “the good and great king Osiris,” which he straightway did. For this reason the education of the young Osiris was entrusted to Pamyles. Thus, it is said, was the festival of the Pamilia instituted.

“In course of time the prophecies concerning Osiris were fulfilled, and he became a great and wise king. The land of Egypt flourished under his rule as it had never done heretofore. Like many another ‘hero-god,’ he set himself the task of civilizing his people, who at his coming were in a very barbarous condition, indulging in cannibalistic and other savage practices. He gave them a code of laws, taught them the arts of husbandry, and showed them the proper rites wherewith to worship the gods. And when he had succeeded in establishing law and order in Egypt he betook himself to distant lands to continue there his work of civilization. So gentle and good was he, and so pleasant were his methods of instilling knowledge into the minds of the barbarians, that they worshipped the very ground whereon he trod. …

Osiris & Crops — Corn

“The character of Osiris as a deity of vegetation is brought out by the legend that he was the first to teach men the use of corn, and by the custom of beginning his annual festival with the tillage of the ground. He is said also to have introduced the cultivation of the vine. In one of the chambers dedicated to Osiris in the great temple of Isis at Philæ the dead body of Osiris is represented with stalks of corn springing from it, and a priest is depicted watering the stalks from a pitcher which he holds in his hand. The accompanying legend sets forth that ‘this is the form of him whom one may not name, Osiris of the mysteries, who springs from the returning waters.’ It would seem impossible to devise a more graphic way of depicting Osiris as a personification of the corn; while the inscription attached to the picture proves that this personification was the kernel of the mysteries of the god, the innermost secret that was only revealed to the initiated. In estimating the mythical character of Osiris, very great weight must be given to this monument. The story that his mangled remains were scattered up and down the land may be a mythical way of expressing either the sowing or the winnowing of the grain. The latter interpretation is supported by the tale that Isis placed the severed limbs of Osiris on a corn-sieve. Or the legend may be a reminiscence of the custom of slaying a human victim as a representative of the corn-spirit, and distributing his flesh or scattering his ashes over the fields to fertilize them.”

“But Osiris was more than a spirit of the corn; he was also a tree-spirit, and this may well have been his[Pg 72] original character, since the worship of trees is naturally older in the history of religion than the worship of the cereals. His character as a tree-spirit was represented very graphically in a ceremony described by Firmicus Maternus. A pine-tree having been cut down, the centre was hollowed out, and with the wood thus excavated an image of Osiris was made, which was then ‘buried’ in the hollow of the tree. Here, again, it is hard to imagine how the conception of a tree as tenanted by a personal being could be more plainly expressed. The image of Osiris thus made was kept for a year and then burned, exactly as was done with the image of Attis which was attached to the pine-tree. The ceremony of cutting the tree, as described by Firmicus Maternus, appears to be alluded to by Plutarch. It was probably the ritual counterpart of the mythical discovery of the body of Osiris enclosed in the erica-tree. We may conjecture that the erection of the Tatu pillar at the close of the annual festival of Osiris was identical with the ceremony described by Firmicus; it is to be noted that in the myth the erica-tree formed a pillar in the king’s house. Like the similar custom of cutting a pine-tree and fastening an image to it, in the rites of Attis, the ceremony perhaps belonged to the class of customs of which the bringing in the Maypole is among the most familiar. As to the pine-tree in particular, at Denderah the tree of Osiris is a conifer, and the coffer containing the body of Osiris is here depicted as enclosed within the tree. A pine-cone often appears on the monuments as an offering presented to Osiris, and a manuscript of the Louvre speaks of the cedar as sprung from him. The sycamore and the tamarisk are also his trees. In inscriptions he is spoken of as residing in them, and his mother Nut is frequently portrayed in a sycamore. In a sepulchre at How[Pg 73] (Diospolis Parva) a tamarisk is depicted overshadowing the coffer of Osiris; and in the series of sculptures which illustrate the mystic history of Osiris in the great temple of Isis at Philæ a tamarisk is figured with two men pouring water on it. The inscription on this last monument leaves no doubt, says Brugsch, that the verdure of the earth was believed to be connected with the verdure of the tree, and that the sculpture refers to the grave of Osiris at Philæ, of which Plutarch tells us that it was overshadowed by a methide plant, taller than any olive-tree. This sculpture, it may be observed, occurs in the same chamber in which the god is depicted as a corpse with ears of corn sprouting from him. In inscriptions he is referred to as ‘the one in the tree,’ ‘the solitary one in the acacia,’ and so forth. On the monuments he sometimes appears as a mummy covered with a tree or with plants. It accords with the character of Osiris as a tree-spirit that his worshippers were forbidden to injure fruit-trees, and with his character as a god of vegetation in general that they were not allowed to stop up wells of water, which are so important for the irrigation of hot southern lands.”

Comparing Osiris to Ra

“Sir J.G. Frazer goes on to combat the theory of Lepsius that Osiris was to be identified with the sun-god Ra. Osiris, says the German scholar, was named Osiris-Ra even in the Book of the Dead, and Isis, his spouse, is often called the royal consort of Ra. This identification, Sir J.G. Frazer thinks, may have had a political significance. He admits that the myth of Osiris might express the daily appearance and disappearance of the sun, and points out that most of the writers who favour the solar theory are careful to indicate that it is the daily, and not the annual, course of the sun to which they understand the myth to apply. But, then, why, pertinently asks Sir J. G. Frazer, was[Pg 74] it celebrated by an annual ceremony? “This fact alone seems fatal to the interpretation of the myth as descriptive of sunset and sunrise. Again, though the sun may be said to die daily, in what sense can it be said to be torn in pieces?”

Osiris As the Moon

“Plutarch says that some of the Egyptian philosophers interpreted Osiris as the moon, “because the moon, with her humid and generative light, is favourable to the propagation of animals and the growth of plants.” Among primitive peoples the moon is regarded as a great source of moisture. Vegetation is thought to flourish beneath her pale rays, and she is understood as fostering the multiplication of the human species as well as animal and plant life. Sir J. G. Frazer enumerates several reasons to prove that Osiris possessed a lunar significance. Briefly these are that he is said to have lived or reigned twenty-eight years, the mythical expression of a lunar month, and that his body is said to have been rent into fourteen pieces—”This might be interpreted as the waning moon, which appears to lose a portion of itself on each of the fourteen days that make up the second half of the lunar month.” Typhon found the body of Osiris at the full moon; thus its dismemberment would begin with the waning of the moon.

Primitive Conceptions of the Moon

“Primitive man explains the waning moon as actually dwindling, and it appears to him as if it is being broken in pieces or eaten away. The Klamath Indians of South-west Oregon allude to the moon as ‘the One Broken in Pieces,’ and the Dacotas believe that when the moon is full a horde of mice begin to nibble at one side of it until they have devoured the whole. To continue Sir J.G. Frazer’s argument, he quotes Plutarch[Pg 75] to the effect that at the new moon of the month Phanemoth, which was the beginning of spring, the Egyptians celebrated what they called ‘the entry of Osiris into the moon’; that at the ceremony called the ‘Burial of Osiris’ they made a crescent-shaped chest, “because the moon when it approaches the sun assumes the form of a crescent and vanishes”; and that once a year, at the full moon, pigs (possibly symbolical of Set, or Typhon) were sacrificed simultaneously to the moon and to Osiris. Again, in a hymn supposed to be addressed by Isis to Osiris it is said that Thoth

Placeth thy soul in the barque Maāt

In that name which is thine of god-moon.

And again:

Thou who comest to us as a child each month,

We do not cease to contemplate thee.

Thine emanation heightens the brilliancy

Of the stars of Orion in the firmament.

In this hymn Osiris is deliberately identified with the moon.[6]

“In effect, then, Sir James Frazer’s theory regarding Osiris is that he was a vegetation or corn god, who later became identified, or confounded, with the moon. But surely it is as reasonable to suppose that it was because of his status as moon-god that he ranked as a deity of vegetation.

“A brief consideration of the circumstances connected with lunar worship might lead us to some such supposition. The sun in his status of deity requires but little explanation. The phenomena of growth are attributed to his agency at an early period of human thought, and it is probable that wind, rain, and other atmospheric manifestations are likewise credited to his[Pg 76] action, or regarded as emanations from him. Especially is this the case in tropical climates, where the rapidity of vegetable growth is such as to afford to man an absolute demonstration of the solar power. By analogy, then, that sun of the night, the moon, comes to be regarded as an agency of growth, and primitive peoples attribute to it powers in this respect almost equal to those of the sun. Again, it must be borne in mind that, for some reason still obscure, the moon is regarded as the great reservoir of magical power. The two great orbs of night and day require but little excuse for godhead. To primitive man the sun is obviously godlike, for upon him the barbarian agriculturist depends for his very existence, and there is behind him no history of an evolution from earlier forms. It is likewise with the moon-god. In the Libyan desert at night the moon is an object which dominates the entire landscape, and it is difficult to believe that its intense brilliance and all-pervading light must not have deeply impressed the wandering tribes of that region with a sense of reverence and worship. Indeed, reverence for such an object might well precede the worship of a mere corn and tree spirit, who in such surroundings could not have much scope for the manifestation of his powers. We can see, then, that this moon-god of the Neolithic Nubians, imported into a more fertile land, would speedily become identified with the powers of growth through moisture, and thus with the Nile itself.

Osiris in his character of god of the dead affords no great difficulties of elucidation, and in this one figure we behold the junction of the ideas of the moon, moisture, the under-world, and death—in fact, all the phenomena of birth and decay.

Osiris and the Persephone Myth

“The reader cannot fail to have observed the very close resemblance between the myth of Osiris and that of Demeter and Kore, or Persephone. Indeed, some of the adventures of Isis, notably that concerning the child of the king of Byblos, are practically identical with incidents in the career of Demeter. It is highly probable that the two myths possessed a common origin. But whereas in the Greek example we find the mother searching for her child, in the Egyptian myth the wife searches for the remains of her husband. In the Greek tale we have Pluto as the husband of Persephone and the ruler of the under-world also regarded, like Osiris, as a god of grain and growth, whilst Persephone, like Isis, probably personifies the grain itself. In the Greek myth we have one male and two female principles, and in the Egyptian one male and one female. The analogy could perhaps be pressed further by the inclusion in the Egyptian version of the goddess Nephthys, who was a sister-goddess to Isis or stood to her in some such relationship. It would seem, then, as if the Hellenic myth had been sophisticated by early Egyptian influences, perhaps working through a Cretan intercommunication.

It remains, then, to regard Osiris in the light of ruler of the underworld. To some extent this has been done in the chapter which deals with the Book of the Dead. The god of the underworld, as has been pointed out, is in nearly every instance a god of vegetable growth, and it was not because Osiris was god of the dead that he presided over fertility, but the converse. To speak more plainly, Osiris was first god of fertility, and the circumstance that he presided over the underworld was a later innovation. But it[Pg 78] was not adventitious; it was the logical outcome of his status as god of growth.

Osirian Theory

“We must also take into brief consideration his personification of Ra, whom he meets, blends with, and under whose name he nightly sails through his own dominions. This would seem like the fusion of a sun and moon myth; the myth of the sun travelling nightly beneath the earth fused with that of the moon’s nocturnal journey across the vault of heaven. A moment’s consideration will show how this fusion took place. Osiris was a moon-god. That circumstance accounts for one half of the myth; the other half is to be accounted for as follows: Ra, the sun-god, must perambulate the underworld at night if he is to appear on the fringes of the east in the morning. But Osiris as a lunar deity, and perhaps as the older god, as well as in his character as god of the underworld, is already occupying the orbit he must trace. The orbits of both deities are fused in one, and there would appear to be some proof of this in the fact that, in the realm of Seker, Afra (or Ra-Osiris) changes the direction of his journey from north to south to a line due east toward the mountains of sunrise. The fusion of the two myths is quite a logical one, as the moon during the night travels in the same direction as the sun has taken during the day—that is, from east to west.

“It will readily be seen how Osiris came to be regarded not only as god and judge of the dead, but also as symbolical of the resurrection of the body of man. Sir James Frazer lays great stress upon a picture of Osiris in which his body is shown covered with sprouting shoots of corn, and he seems to be of opinion that this is positive evidence that Osiris was a corn-god.[Pg 79] In our view the picture is simply symbolical of resurrection. The circumstance that Osiris is represented in the picture as in the recumbent position of the dead lends added weight to this supposition. The corn-shoot is a world-wide symbol of resurrection. In the Eleusinian mysteries a shoot of corn was shown to the neophytes as typical of physical rebirth, and a North American Indian is quoted by Loskiel, one of the Moravian Brethren, as having spoken: “We Indians shall not for ever die. Even the grains of corn we put under the earth grow up and become living things.” Among the Maya of Central America, as well as among the Mexicans, the maize-goddess has a son, the young, green, tender shoot of the maize plant, who is strongly reminiscent of Horus, the son of Osiris, and who may be taken as typical of bodily resurrection. Later the vegetation myth clustering round Osiris was metamorphosed into a theological tenet regarding human resurrection, and Osiris was believed to have been once a human being who had died and had been dismembered. His body, however, was made whole again by Isis, Anubis and Horus acting upon the instructions of Thoth. A good deal of magical ceremony appears to have been mingled with the process, and this in turn was utilized in the case of every dead Egyptian by the priests in connexion with the embalmment and burial of the dead in the hope of resurrection. Osiris, however, was regarded as the principal cause of human resurrection, and he was capable of giving life after death because he had attained to it. He was entitled ‘Eternity and Everlastingness,’ and he it was who made men and women to be born again. This conception of resurrection appears to have been in vogue in Egypt from very early times. The great authority upon Osiris is the Book of the Dead, which[Pg 80] might well be called the ‘Book of Osiris,’ and in which are recounted his daily doings and his nightly journeyings in his kingdom of the underworld.” Spence, Lewis. Myths and Legends Ancient Egypt.

.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.