THE

GREAT SOUTH:

A RECORD OF JOURNEYS

IN

LOUISIANA, TEXAS, THE INDIAN TERRITORY, MISSOURI, ARKANSAS,

MISSISSIPPI, ALABAMA, GEORGIA, FLORIDA, SOUTH CAROLINA,

NORTH CAROLINA, KENTUCKY, TENNESSEE, VIRGINIA,

WEST VIRGINIA, AND MARYLAND.

BY

EDWARD KING.

PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED FROM ORIGINAL SKETCHES

BY J WELLS CHAMPNEY.

AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY,

HARTFORD, CONN.

1875.

https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/king/king.html

ON THE OCLAWAHA FLORIDA.

PREFACE.

THIS book is the record of an extensive tour of observation through the States of the South and South-west during the whole of 1873, and the Spring and Summer of 1874.

The journey was undertaken at the instance of the publishers of Scribner’s Monthly, who desired to present to the public, through the medium of their popular periodical, an account of the material resources, and the present social and political condition, of the people in the Southern States. The author and the artists associated with him in the preparation of the work, traveled more than twenty-five thousand miles; visited nearly every city and town of importance in the South; talked with men of all classes, parties and colors; carefully investigated manufacturing enterprises and sites; studied the course of politics in each State since the advent of reconstruction; explored rivers, and penetrated into mountain regions heretofore rarely visited by Northern men. They were everywhere kindly and generously received by the Southern people; and they have endeavored, by pen and pencil, to give the reading public a truthful picture of life in a section which has, since the close of a devastating war, been overwhelmed by a variety of misfortunes, but upon which the dawn of a better day is breaking.

The fifteen ex-slave States cover an area of more than 880,000 square miles, and are inhabited by fourteen millions of people. The aim of the author has been to tell the truth

as exactly and completely as possible in the time and space allotted him, concerning the characteristics of this region and its inhabitants.

The popular favor accorded in this country and Great Britain to the fifteen illustrated articles descriptive of the South which have appeared in Scribner’s Monthly, has led to the preparation of the present volume. Much of the material which has appeared in Scribner will be found in its pages; the whole has, however, been re-written, re-arranged, and, with numerous additions, is now simultaneously offered to the English-speaking public on both sides of the Atlantic.

To the talent and skill of Mr. J. WELLS CHAMPNEY, the artist who accompanied the author during the greater part of the journey, the public is indebted for more than four hundred of the superb sketches of Southern life, character, and scenery which illustrate this volume. The other artists who have contributed have done their work faithfully and well.

NEW YORK, November, 1874.

CONTENTS.

- PREFACE . . . . . 1

- DEDICATION . . . . . 3

- I. LOUISIANA, PAST AND PRESENT . . . . . 17

- II. THE FRENCH QUARTER OF NEW ORLEANS–THE REVOLUTION AND ITS EFFECTS . . . . . 28

- III. THE CARNIVAL–THE FRENCH MARKETS . . . . . 38

- IV. THE COTTON TRADE–THE NEW ORLEANS LEVÉES . . . . . 50

- V. THE CANALS AND THE LAKE–THE AMERICAN QUARTER . . . . . 59

- VI. ON THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER–THE LEVÉE SYSTEM–RAILROADS–THE FORT ST. PHILIP CANAL . . . . . 67

- VII. THE INDUSTRIES OF LOUISIANA–A SUGAR PLANTATION–THE TECHE COUNTRY . . . . . 78

- VIII. THE POLITICAL SITUATION IN LOUISIANA . . . . . 89

- IX. “HO! FOR TEXAS”–GALVESTON . . . . . 99

- X. A VISIT TO HOUSTON . . . . . 110

- XI. PICTURES FROM PRISON AND FIELD . . . . . 117

- XII. AUSTIN, THE TEXAN CAPITAL–POLITICS–SCHOOLS . . . . . 127

- XIII. THE TRUTH ABOUT TEXAS–THE JOURNEY BY STAGE TO SAN ANTONIO . . . . . 137

- XIV. AMONG THE OLD SPANISH MISSIONS . . . . . 147

- XV. THE PEARL OF THE SOUTH–WEST . . . . . 157

- XVI. THE PLAINS–THE CATTLE TRADE . . . . . 167

- XVII. DENISON–TEXAN CHARACTERISTICS . . . . . 175

- XVIII. THE NEW ROUTE TO THE GULF . . . . . 186

- XIX. THE “INDIAN TERRITORY” . . . . . 197

- XX. RAILROAD PIONEERING–INDIAN TYPES AND CHARACTER . . . . . 204

- XXI. MISSOURI–ST. LOUIS, PAST AND PRESENT . . . . . 215

- XXII. ST. LOUIS GERMANS AND AMERICANS–SPECULATIVE PHILOSOPHY–EDUCATION . . . . . 222

- XXIII. COMMERCE OF ST. LOUIS–THE NEW BRIDGE OVER THE MISSISSIPPI . . . . . 230

- XXIV. THE MINERAL WEALTH OF MISSOURI . . . . . 237

- XXV. TRADE IN ST. LOUIS–THE PRESS–KANSAS CITY–ALONG THE MISSISSIPPI–THE CAPITAL . . . . . 246

- XXVI. DOWN THE MISSISSIPPI FROM ST. LOUIS . . . . . 257

- XXVII. MEMPHIS, THE CHIEF CITY OF TENNESSEE–ITS TRADE AND CHARACTER . . . . . 264

- XXVIII. THE “SUPPLY” SYSTEM IN THE COTTON COUNTRY, AND ITS RESULTS–NEGRO LABOR–PRESENT PLANS OF WORKING COTTON PLANTATIONS–THE BLACK MAN IN THE MISSISSIPPI VALLEY . . . . . 270

- XXIX. ARKANSAS–ITS RESOURCES–ITS PEOPLE–ITS POLITICS–TAXATION–THE HOT SPRINGS . . . . . 278

- XXX. VICKSBURG AND NATCHEZ, MISSISSIPPI–SOCIETY AND POLITICS—-A LOUISIANA PARISH JURY . . . . . 287

- XXXI. LIFE ON COTTON PLANTATIONS . . . . . 297

- XXXII. MISSISSIPPI–ITS TOWNS–FINANCES–SCHOOLS–PLANTATION DIFFICULTIES . . . . . 311

- XXXIII. MOBILE, THE CHIEF CITY OF ALABAMA . . . . . 319

- XXXIV. THE RESOURCES OF ALABAMA–VISITS TO MONTGOMERY AND SELMA . . . . . 328

- XXXV. NORTHERN ALABAMA–THE TENNESSEE VALLEY–TRAITS OF CHARACTER–EDUCATION . . . . . 339

- XXXVI. THE SAND-HILL REGION–AIKEN–AUGUSTA . . . . . 344

- XXXVII. ATLANTA–GEORGIA POLITICS–THE FAILURE OF RECONSTRUCTION . . . . . 350

- XXXVIII. SAVANNAH, THE FOREST CITY–THE RAILWAY SYSTEM OF GEORGIA–MATERIAL PROGRESS OF THE STATE . . . . . 358

- XXXIX. GEORGIAN AGRICULTURE–“CRACKERS”–COLUMBUS–MACON–SOCIETY–ATHENS–THE COAST . . . . . 371

- XL. THE JOURNEY TO FLORIDA–THE PENINSULA’S HISTORY–JACKSONVILLE . . . . . 377

- XLI. UP THE ST. JOHN’S RIVER–TOCOI–ST. AUGUSTINE . . . . . 383

- XLII. ST. AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA–FORT MARION . . . . . 390

- XLIII. THE CLIMATE OF FLORIDA–A JOURNEY TO PALATKA . . . . . 398

- XLIV. ORANGE CULTURE IN FLORIDA–FERTILITY OF THE PENINSULA . . . . . 402

- XLV. UP THE OCLAWAHA TO SILVER SPRING . . . . . 408

- XLVI. THE UPPER ST. JOHN’S–INDIAN RIVER–KEY WEST–POLITICS–THE NEW CONSTITUTION . . . . . 416

- XLVII. SOUTH CAROLINA–PORT ROYAL–THE SEA ISLANDS-THE REVOLUTION . . . . . 422

- XLVIII. ON A RICE PLANTATION IN SOUTH CAROLINA . . . . . 429

- XLIX. CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA . . . . . 438

- L. THE VENICE OF AMERICA-CHARLESTON’S POLITICS–A LOVELY LOWLAND CITY–IMMIGRATION . . . . . 444

- LI. THE SPOLIATION OF SOUTH CAROLINA . . . . . 454

- LII. THE NEGROES IN ABSOLUTE POWER . . . . . 460

- LIII. THE LOWLANDS OF NORTH CAROLINA . . . . . 466

- LIV. AMONG THE SOUTHERN MOUNTAINS–JOURNEY FROM EASTERN TENNESSEE TO WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA . . . . . 474

- LV. ACROSS THE “SMOKY” TO WAYNESVILLE–THE MASTER CHAIN OF THE ALLEGHANIES. . . . . . 480

- LVI. THE “SUGAR FORK” AND DRY FALLS–WHITESIDE MOUNTAIN . . . . . 490

- LVII. ASHEVILLE–THE FRENCH BROAD VALLEY–THE ASCENT OF MOUNT MITCHELL . . . . . 503

- LVIII. THE SOUTH CAROLINA MOUNTAINS–CASCADES AND PEAKS OF NORTHERN GEORGIA. . . . . . 515

- LIX. CHATTANOOGA, THE GATEWAY OF THE SOUTH . . . . . 527

- LX. LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN–THE BATTLES AROUND CHATTANOOGA–KNOXVILLE–EASTERN TENNESSEE . . . . . 536

- LXI. A VISIT TO LYNCHBURG IN VIRGINIA . . . . . 552

- LXII. IN SOUTH-WESTERN VIRGINIA–THE PEAKS OF OTTER–THE MINERAL SPRINGS . . . . . 561

- LXIII. AMONG THE MOUNTAINS–FROM BRISTOL TO LYNCHBURG . . . . . 569

- LXIV. PETERSBURG–A NEGRO REVIVAL MEETING . . . . . 579

- LXV. THE DISMAL SWAMP–NORFOLK–THE COAST . . . . . 588

- LXVI. THE EDUCATION OF NEGROES–THE AMERICAN MISSIONARY ASSOCIATION–THE PEABODY FUND–THE CIVIL RIGHTS BILL . . . . . 596

- LXVII. THE HAMPTON NORMAL INSTITUTE–GENERAL ARMSTRONG’S WORK–FISK UNIVERSITY–BEREA AND OTHER COLLEGES . . . . . 603

- LXVIII. NEGRO SONGS AND SINGERS . . . . . 609

- LXIX. A PEEP AT THE PAST OF VIRGINIA–JAMESTOWN–WILLIAMSBURG–YORKTOWN . . . . . 621

- LXX. RICHMOND–ITS TRADE AND CHARACTER . . . . . 626

- LXXI. THE PARTITION OF VIRGINIA–RECONSTRUCTION AND POLITICS IN WEST AND EAST VIRGINIA . . . . . 639

- LXXII. FROM RICHMOND TO CHARLOTTESVILLE . . . . . 647

- LXXIII. FROM CHARLOTTESVILLE TO STAUNTON, VIRGINIA–THE SHENANDOAH VALLEY–LEXINGTON–THE GRAVES OF GENERAL LEE AND “STONEWALL” JACKSON–FROM GOSHEN TO “WHITE SULPHUR SPRINGS.” . . . . . 656

- LXXIV. GREENBRIER WHITE SULPHUR SPRINGS–FROM THE “WHITE SULPHUR” TO KANAWHA VALLEY–THE MINERAL SPRINGS REGION . . . . . 670

- LXXV. THE KANAWHA VALLEY–MINERAL WEALTH OF WESTERN VIRGINIA . . . . . 681

- LXXVI. DOWN THE OHIO RIVER–LOUISVILLE . . . . . 693

- LXXVII. A VISIT TO THE MAMMOTH CAVE . . . . . 699

- LXXVIII. THE TRADE OF LOUISVILLE . . . . . 707

- LXXIX. FRANKFORT–THE BLUE GRASS REGION–ALEXANDER’S FARM–LEXINGTON . . . . . 713

- LXXX. POLITICS IN KENTUCKY–MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE STATE . . . . . 721

- LXXXI. NASHVILLE AND MIDDLE TENNESSEE . . . . . 726

- LXXXII. A GLANCE AT MARYLAND’S. HISTORY–HER EXTENT AND RESOURCES . . . . . 733

- LXXXIII. THE BALTIMORE AND OHIO RAILROAD . . . . . 741

- LXXXIV. THE TRADE OF BALTIMORE–ITS RAPID AND ASTONISHING GROWTH . . . . . 748

- LXXXV. BALTIMORE AND ITS INSTITUTIONS . . . . . 757

- LXXXVI. SOUTHERN CHARACTERISTICS–STATE PRIDE–THE INFLUENCE OF RAILROADS–POOR WHITES–THEIR HABITS . . . . . 771

- LXXXVII. THE CARRYING OF WEAPONS–MORAL CHARACTER OF THE NEGROES . . . . . 777

- LXXXVIII. DIALECT–FORMS OF EXPRESSION–DIET . . . . . 784

- LXXXIX. IMMIGRATION–THE NEED OF CAPITAL–DIVISION OF THE NEGRO VOTE–THE SOUTHERN LADIES . . . . . 792

- XC. RAMBLES IN VIRGINIA–FREDERICKSBURG–ALEXANDRIA–MOUNT VERNON–ARLINGTON . . . . . 795

ILLUSTRATIONS

AND MAPS.

- Scene on the Oclawaha River, Florida–Frontispiece

- General Map of the Southern States . . . . . 15

- Bienville, the Founder of New Orleans . . . . . 17

- The Cathedral St. Louis–New Orleans . . . . . 18

- “A blind beggar hears the rustling of her gown, and stretches out his trembling hand for alms,” . . . . . 19

- “A black girl looks wonderingly into the holy-water font” . . . . . 19

- The Archbishop’s Palace, New Orleans . . . . . 20

- “Some aged private dwellings, rapidly decaying,” . . . . . 25

- A brace of old Spanish Governors.-From portraits owned by Hon. Charles Gayarré, of New Orleans . . . . . 26

- “And where to-day stands a fine Equestrian Statue of the Great General” . . . . . 27

- “A lazy negro, recumbent in a cart” . . . . . 29

- “The negro nurses stroll on the sidewalks, chattering in quaint French to the little children” . . . . . 30

- “The interior garden, with its curious shrine” . . . . . 31

- “The new Ursuline Convent, New Orleans . . . . . 32

- “And while they chatter like monkeys, even about politics, they gesticulate violently” . . . . . 35

- “The old French and Spanish cemeteries present long streets of cemented walls” . . . . . 36

- The St. Louis Hotel, New Orleans . . . . . 37

- The Carnival-“White and black join in its masquerading.” . . . . . 38

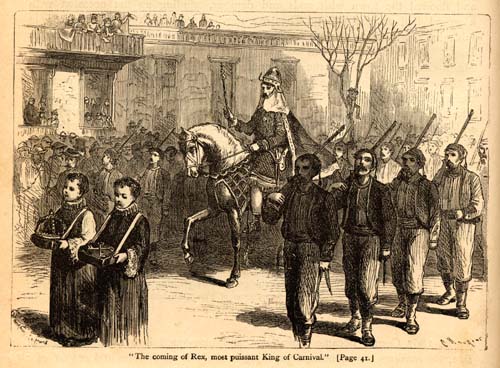

- “The coming of Rex, most puissant King of Carnival” . . . . . 40

- “The Boeuf-Gras-the fat ox-is led in the procession” . . . . . 41

- “When Rex and his train enter the queer old streets, the balconies are crowded with spectators” . . . . . 42

- “The joyous, grotesque maskers appear upon the ball-room floor” . . . . . 43

- “Many bright eyes are in vain endeavoring to pierce the disguise” . . . . . 45

- “The French market at sunrise on Sunday morning” . . . . . 46

- “Passing under long, hanging rows of bananas and pine-apples” . . . . . 47

- “One sees delicious types in these markets” . . . . . 48

- “In a long passage, between two of the market buildings, sits a silent Louisiana Indian woman” . . . . . 49

- “Stout colored women, with cackling hens dangling from their brawny hands” . . . . . 49

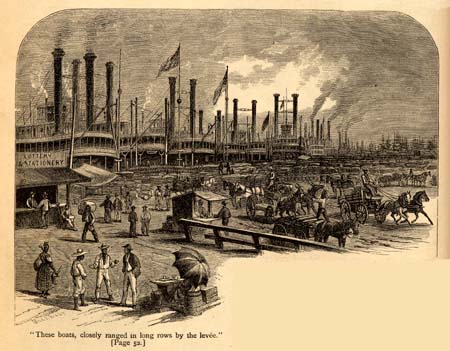

- “These boats, closely ranged in long rows by the levée” . . . . . 50

- “Whenever there is a lull in the work, they sink down on the cotton bales” . . . . . 52

- “Not far from the levée there is a police court, where they especially delight to lounge” . . . . . 52

- “The cotton thieves” . . . . . 55

- “There is the old apple and cake woman” . . . . . 55

- “The Sicilian fruit-seller” . . . . . 56

- “At high water, the juvenile population perches on the beams of the wharves, and enjoys a little quiet fishing” . . . . . 57

- “The polite but consequential negro policeman,” . . . . . 57

- The St. Charles Hotel, New Orleans . . . . . 59

- The New Basin . . . . . 60

- The old Spanish Fort . . . . . 60

- The University of Louisiana, New Orleans . . . . . 61

- The Theatres of New Orleans . . . . . 61

- Christ Church, New Orleans . . . . . 62

- The Canal street Fountain, New Orleans . . . . . 62

- The Charity Hospital, New Orleans . . . . . 63

- The old Maison de Santé, New Orleans . . . . . 63

- The United States Marine Hospital, New Orleans . . . . . 64

- Trinity Church, New Orleans . . . . . 64

- St. Paul’s Church, New Orleans . . . . . 64

- First Presbyterian Church, New Orleans . . . . . 65

- The Catholic Churches of New Orleans-St. Joseph’s, St. Patrick’s Jesuit Church and School . . . . . 65

- The Custom-House, New Orleans . . . . . 66

- The United States Branch Mint, New Orleans . . . . . 66

- “Sometimes the boat stops at a coaling station” . . . . . 68

- “The Wasp” . . . . . 69

- “Some tract of hopelessly irreclaimable, grotesque water wilderness.” (From a painting by Julio.) . . . . . 70

- The monument on the Chalmette battle-field . . . . . 72

- Light-house, South-west Pass . . . . . 74

- “Pilot Town,” South-west Pass . . . . . 75

- “A Nickel for Daddy” . . . . . 77

- “A cheery Chinaman” . . . . . 82

- Sugar-cane Plantation-“The cane is cut down at its perfection” . . . . . 83

- “The beautiful ‘City Park,'” New Orleans . . . . . 87

- Map showing the Distribution of the Colored Population of the United States. (From the U. S. Census Reports) . . . . . 88

- Map of the Gulf States and Arkansas . . . . . 89

- The Supreme Court, New Orleans . . . . . 92

- The United States Barracks, New Orleans . . . . . 93

- Mechanics’ Institute, New Orleans . . . . . 95

- Going to Texas . . . . . 99

- “It is only a few steps from an oleander grove to the surf.” . . . . . 102

- “The mule-carts unloading schooners anchored lightly in the shallow waves” . . . . . 103

- “Galveston has many huge cotton-presses” . . . . . 104

- The Custom-House, Galveston . . . . . 105

- “Primitive enough is this Texan jail” . . . . . 106

- The Catholic Cathedral, Galveston . . . . . 107

- “Watch the negro fisherman as he throws his line horizonward” . . . . . 108

- “The cotton-train is already a familiar spectacle on all the great trunk lines” . . . . . 110

- “There are some notable nooks and bluffs along the bayou” . . . . . 112

- “The Head-quarters of the Masonic Lodges of the State” . . . . . 113

- “The railroad depots are everywhere crowded with negroes, immigrants, tourists and speculators” . . . . . 113

- The New Market, Houston . . . . . 114

- “The ragged urchin with his saucy face” . . . . . 114

- “The negro on his dray, racing good-humoredly with his fellows” . . . . . 115

- “The auctioneer’s young man” . . . . . 116

- Sam Houston . . . . . 117

- View on the Trinity River . . . . . 118

- “We frequently passed large gangs of the convicts chopping logs in the forest by the roadside” . . . . . 119

- “Satanta had seated himself on a pile of oakum” . . . . . 121

- “As the train passes, the negroes gather in groups to gaze at it until it disappears in the distance” . . . . . 123

- The State Capitol, Austin . . . . . 127

- The State Insane Asylum, Austin . . . . . 128

- The Texas Military Institute, Austin . . . . . 128

- The Governor’s Mansion, Austin . . . . . 129

- The Alamo Monument, Austin . . . . . 131

- The Land Office of Texas, Austin . . . . . 133

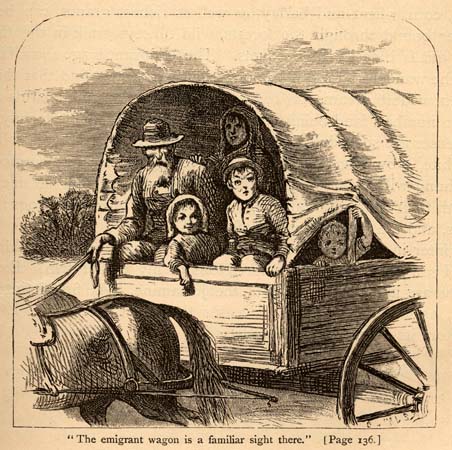

- “The emigrant wagon is a familiar sight there” . . . . . 135

- Sunning themselves–“A group of Mexicans, lounging by a wall” . . . . . 140

- “We encounter wagons drawn by oxen” . . . . . 141

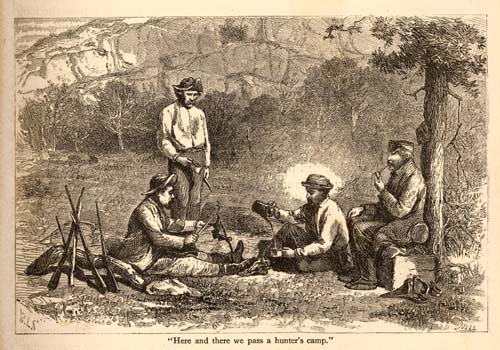

- “Here and there we pass a hunter’s camp” . . . . . 143

- “We pass groups of stone houses” . . . . . 146

- “The vast pile of ruins known as the San José Mission” . . . . . 147

- The old Concepcion Mission, near San Antonio, Texas . . . . . 151

- An old window in the San José Mission . . . . . 155

- “An umbrella and candlestick graced the christening font” . . . . . 155

- “The comfortable country-house so long occupied by Victor Considerant” . . . . . 156

- The San Antonio River–“Its blueish current flows in a narrow but picturesque channel” . . . . . 157

- The source of the San Antonio River . . . . . 157

- San Pedro Springs–“The Germans have established their beer gardens” . . . . . 158

- “Every few rods there is a waterscape in miniature” . . . . . 158

- “The river passes under bridges, by arbors and bath-houses” . . . . . 159

- The Ursuline Convent, San Antonio . . . . . 159

- St. Mary’s Church, San Antonio . . . . . 160

- A Mexican Hovel . . . . . 161

- The Military Plaza, San Antonio . . . . . 161

- “The Mexicans slowly saw and carve the great stones” . . . . . 162

- “The elder women wash clothes by the brookside” . . . . . 163

- Mexican types in San Antonio . . . . . 164

- “The remnant of the old Fort of the Alamo” . . . . . 165

- “The horsemen from the plains” . . . . . 167

- “The candy and fruit merchants lazily wave their fly-brushes” . . . . . 168

- A Mexican beggar . . . . . 168

- “The citizens gather at San Antonio, and discuss measures of vengeance” . . . . . 170

- A Texan Cattle-Drover . . . . . 171

- Military Head-quarters, San Antonio . . . . . 172

- Negro Soldiers of the San Antonio Garrison . . . . . 173

- Scene in a Gambling House–“Playing Keno,” Denison, Texas . . . . . 175

- “Men, drunk and sober, danced to rude music”. . . . . . 176

- “Red Hall” . . . . . 178

- The Public Square in Sherman, Texas . . . . . 180

- “With swine that trotted hither and yon” . . . . . 181

- Bridge over the Red River–(Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway) . . . . . 182

- The New Route to the Gulf . . . . . 186

- “The Pet Conductor” . . . . . 188

- “Charlie” . . . . . 188

- Our Special Train . . . . . 189

- “A stock-train from Sedalia was receiving a squealing and bellowing freight” . . . . . 190

- “The old Hospital,” Fort Scott . . . . . 191

- Bridge over the Marmiton River, near Fort Scott . . . . . 192

- A Street in Parsons, Kansas . . . . . 193

- A Kansas Herdsman . . . . . 193

- A Kansas Farm-yard . . . . . 194

- “The Little Grave, with the slain horses lying upon it” . . . . . 195

- “The stone house which the graceless Kaw has turned into a stable for his pony” . . . . . 195

- “The warrior galloping across the fields” . . . . . 196

- Monument erected to the memory of Brevet-Major E. A. Ogden, near Fort Riley, Kansas . . . . . 196

- An Indian Territorial Mansion . . . . . 197

- A Creek Indian . . . . . 199

- Bridge across the North Fork of the Canadian River, Indian Territory (M. K. and T. Railway) . . . . . 199

- An Adopted Citizen . . . . . 200

- An Indian Stock-Drover . . . . . 201

- “The ball-players are fine specimens of men” . . . . . 202

- A Gentleman from the Arkansas Border . . . . . 203

- Limestone Gap, Indian Territory . . . . . 204

- “Coming in the twilight to a region where great mounds reared their whale-backed heights” . . . . . 205

- A “Terminus” Rough . . . . . 206

- “We came to the bank of the Grand River, on a hill beyond which was the Post of Fort Gibson” . . . . . 206

- A Negro Boy at the Ferry . . . . . 208

- “We found the ferries obstructed by masses of floating ice” . . . . . 209

- “They wore a prim, Shakerish costume” . . . . . 210

- A Trader among the Indians . . . . . 210

- “The Asbury Manual Labor School,” in the Creek domain . . . . . 211

- The Toll-Bridge at Limestone Gap, Indian Territory . . . . . 213

- “Looking down on the St. Louis of to-day, from the high roof of the Insurance temple” . . . . . 215

- “Where now stands the great stone Cathedral” . . . . . 216

- The old Chouteau Mansion (as it was) . . . . . 217

- The St. Louis Life Insurance Company’s Building . . . . . 218

- “In those days the houses were nearly all built of hewn logs” . . . . . 218

- “The crows awaiting transportation across the stream has always been of the most cosmopolitan and motley character” . . . . . 220

- The Court-House, St. Louis . . . . . 222

- Thomas H. Benton (for thirty years United States Senator from Missouri) . . . . . 223

- William T. Harris, editor of the St. Louis “Journal of Speculative Philosophy” . . . . . 226

- The High School, St. Louis . . . . . 228

- Washington University, St. Louis . . . . . 229

- The new Post-Office and Custom-House in construction at St. Louis . . . . . 230

- The new Bridge over the Mississippi at St. Louis . . . . . 233

- View of the Caisson of the East Abutment of the St. Louis Bridge, as it appeared during construction . . . . . 234

- The building of the East Pier of the St. Louis Bridge . . . . . 235

- In the “Cut” at Iron Mountain, Missouri . . . . . 237

- At the Vulcan Iron Works, Carondelet . . . . . 238

- The Furnace, Iron Mountain, Missouri . . . . . 241

- The Summit of Pilot Knob, Iron County, Missouri . . . . . 243

- The “Tracks,” Pilot Knob, Missouri . . . . . 244

- Map of Missouri . . . . . 245

- View in Shaw’s Garden, St. Louis . . . . . 246

- Statue to Thomas H. Benton, in Lafayette Park. . . . . . 247

- The “Four Courts” Building, St. Louis . . . . . 248

- The Gratiot Street Prison, St. Louis . . . . . 248

- First Presbyterian Church, St. Louis . . . . . 249

- Christ Church, St. Louis . . . . . 250

- The Missouri Capitol, at Jefferson City . . . . . 254

- “The Cheery Minstrel” . . . . . 255

- The Steamer “Great Republic” a Mississippi River Boat . . . . . 257

- “Down the steep banks would come kaleidoscopic processions of negroes and flour barrels” . . . . . 258

- The Levée at Cairo, Illinois . . . . . 259

- An Inundated Town on the Mississippi’s bank . . . . . 260

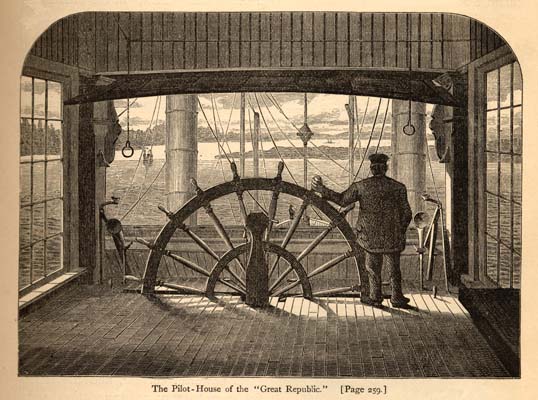

- The Pilot-House of the “Great Republic” . . . . . 261

- A Crevasse in the Mississippi River’s Banks . . . . . 262

- View in the City Park at Memphis, Tennessee . . . . . 264

- The Carnival at Memphis, Tennessee–“The gorgeous pageants of the mysterious Memphi” . . . . . 268

- A Steamboat Torch-Basket . . . . . 277

- View on the Arkansas River at Little Rock . . . . . 279

- The Arkansas State Capitol, Little Rock . . . . . 281

- The Hot Springs, Arkansas . . . . . 286

- Vicksburg, Mississippi . . . . . 287

- The National Cemetery at Vicksburg, Mississippi . . . . . 288

- The Gamblers’ Graves, Vicksburg, Mississippi. . . . . . 289

- Colonel Vick, of Vicksburg, Mississippi, Planter . . . . . 289

- Natchez-under-the-Hill, Mississippi . . . . . 291

- View in Brown’s Garden, Natchez, Mississippi . . . . . 292

- Avenue in Brown’s Garden, Natchez, Mississippi . . . . . 293

- A Mississippi River Steamer arriving at Natchez in the night . . . . . 294

- “Sah?” . . . . . 296

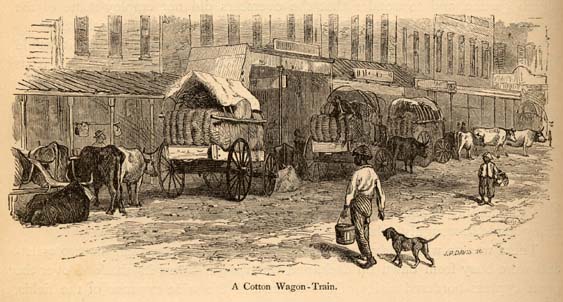

- A Cotton Wagon-Train . . . . . 302

- A Cotton-Steamer . . . . . 304

- Scene on a Cotton Plantation . . . . . 307

- Baton Rouge, Louisiana . . . . . 309

- The Red River Raft as it Was . . . . . 310

- Map showing the Cotton Region of the United States. (From the U. S. Census Reports.) . . . . . 312

- Map of South Carolina, Georgia, Florida and Alabama . . . . . 313

- The Mississippi State Capitol at Jackson . . . . . 313

- “At the proper seasons, one sees in the long main street of the town, lines of emigrant wagons,” . . . . . 314

- “The negroes migrate to Louisiana and Texas in search of paying labor” . . . . . 318

- On the Bay Road near Mobile, Alabama . . . . . 319

- “Mobile Bay lay spread out before me” . . . . . 320

- “A negro woman fished silently in a little pool” . . . . . 321

- The Custom-House, Mobile, Alabama . . . . . 322

- Bank of Mobile and Odd Fellows’ Hall, Mobile, Alabama . . . . . 323

- The Marine and City Hospitals, Mobile, Ala . . . . . 324

- Trinity Church, Mobile, Alabama . . . . . 324

- In the City Park, Mobile–“Ebony nurse-maids flirt with their lovers” . . . . . 325

- In the City Park, Mobile–“Squirrels frolic with the children” . . . . . 326

- Barton Academy, Mobile, Alabama . . . . . 326

- Christ Church, Mobile, Alabama . . . . . 327

- The Alabama State Capitol, at Montgomery . . . . . 332

- The Market-Place at Montgomery, Alabama . . . . . 334

- The Cotton-Plant . . . . . 343

- A Street Scene in Augusta, Georgia . . . . . 344

- A Bell-Tower in Augusta, Georgia . . . . . 347

- A Confederate Soldier’s Grave, at Augusta, Ga. . . . . . 348

- Sunset over Atlanta, Georgia . . . . . 350

- The State-House, Atlanta, Georgia . . . . . 353

- An Up-Country Cotton-Press . . . . . 357

- View on the Savannah River, near Savannah, Georgia . . . . . 358

- General Oglethorpe, the Founder of Savannah . . . . . 359

- The Pulaski Monument in Savannah, Georgia. . . . . . 360

- A Spanish Dagger-Tree, Savannah . . . . . 361

- “Looking down from the bluff,” Savannah . . . . . 362

- “The huge black ships swallowed bale after bale” . . . . . 363

- An old Stairway on the Levée at Savannah . . . . . 364

- The Custom-House at Savannah . . . . . 365

- View in Bonaventure Cemetery, Savannah . . . . . 365

- The Independent Presbyterian Church, Savannah . . . . . 366

- View in Forsyth Park, Savannah . . . . . 367

- “Forsyth park contains a massive fountain” . . . . . 368

- A Savannah Sergeant of Police . . . . . 369

- General Sherman’s Head-quarters, Savannah . . . . . 370

- A pair of Georgia “Crackers” . . . . . 372

- The Eagle and Phoenix Cotton-Mills, Columbus, Georgia . . . . . 373

- The old Fort on Tybee Island, Georgia . . . . . 375

- Happiness . . . . . 376

- Moonlight over Jacksonville, Florida . . . . . 377

- Jacksonville, on the St. John’s River, Florida . . . . . 381

- Residence of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe, at Mandarin, Florida . . . . . 383

- Green Cove Springs, on the St. John’s River, Fla. . . . . . 384

- On the Road to St. Augustine, Florida . . . . . 386

- A Street in St. Augustine, Florida . . . . . 387

- St. Augustine, Florida–“An ancient gateway” . . . . . 388

- The Remains of a Citadel at Matanzas Inlet . . . . . 391

- View of Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida . . . . . 392

- Light-house on Anastasia Island, near St. Augustine, Florida . . . . . 393

- View of the Entrance to Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida . . . . . 394

- “The old sergeant in charge” . . . . . 395

- The Cathedral, St. Augustine, Florida . . . . . 396

- The Banana–“At Palatka, we first found the banana in profusion” . . . . . 400

- “Just across the river from Palatka lies the beautiful orange grove owned by Colonel Hart” . . . . . 402

- Entrance to Colonel Hart’s orange grove, opposite Palatka . . . . . 404

- The Guardian Angel . . . . . 407

- A Peep into a Forest on the Oclawaha . . . . . 409

- We would brush past the trees and vines” . . . . . 410

- The “Marion” at Silver Spring . . . . . 412

- Shooting at Alligators . . . . . 414

- View on the upper St. John’s River, Florida . . . . . 416

- Sunrise at Enterprise, St. John’s River, Florida. . . . . . 419

- A Country Cart . . . . . 421

- View of a Rice-field in South Carolina . . . . . 429

- Negro Cabins on a Rice Plantation . . . . . 431

- “The women were dressed in gay colors” . . . . . 432

- “With forty or fifty pounds of rice-stalks on their heads” . . . . . 432

- A Pair of Mule-Boots . . . . . 434

- A “Trunk-Minder” . . . . . 434

- Unloading the Rice-Barges . . . . . 435

- “At the winnowing-machine” . . . . . 436

- “Aunt Bransom”–A venerable ex-slave on a South Carolina Rice Plantation . . . . . 437

- View from Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor . . . . . 438

- The old Charleston Post-Office . . . . . 440

- Houses on the Battery, Charleston . . . . . 441

- A Charleston Mansion . . . . . 442

- The Spire of St. Philip’s Church, Charleston . . . . . 443

- The Orphan House, Charleston . . . . . 444

- The Battery, Charleston . . . . . 445

- The Grave of John C. Calhoun, Charleston . . . . . 446

- The Ruins of St. Finbar Cathedral, Charleston. . . . . . 447

- “The highways leading out of the city are all richly embowered in loveliest foliage” . . . . . 449

- Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston . . . . . 450

- Garden in Mount Pleasant, opposite Charleston . . . . . 452

- Peeping Through . . . . . 453

- A Future Politician . . . . . 459

- The State-House at Columbia, South Carolina . . . . . 460

- Sketches of South Carolina State Officers and Legislators under the Moses Administration . . . . . 462

- Iron Palmetto in the State-House Yard at Columbia . . . . . 465

- A Wayside Sketch . . . . . 473

- “The Small Boy” . . . . . 474

- “The Judge” . . . . . 476

- The Judge shows the Artist’s Sketch-Book . . . . . 479

- “The family sang line by line” . . . . . 481

- A Mountain Farmer . . . . . 482

- “We caught a glimpse of the symmetrical Catalouche mountain” . . . . . 483

- The Cañon of the Catalouche as seen from “Bennett’s . . . . . 484

- Mount Pisgah, Western North Carolina . . . . . 486

- The Carpenter–A Study from Waynesville Life . . . . . 487

- View on Pigeon River, near Waynesville . . . . . 488

- The Dry Fall of the Sugar Fork, Blue Ridge, North Carolina . . . . . 490

- View near Webster, North Carolina . . . . . 492

- Lower Sugar Fork Fall, Blue Ridge, North Carolina . . . . . 495

- The Devil’s Court-House, Whiteside Mountain. . . . . . 499

- Jonas sees the Abyss . . . . . 501

- Asheville, North Carolina, from “Beaucatcher Knob” . . . . . 504

- View near Warm Springs, on the French Broad River . . . . . 506

- Lover’s Leap, French Broad River, Western North Carolina . . . . . 508

- View on the Swannanoa River, near Asheville, Western North Carolina . . . . . 509

- First Peep at Patton’s . . . . . 510

- The “Mountain House,” on the way to Mount Mitchell’s Summit . . . . . 511

- View of Mount Mitchell . . . . . 512

- The Judge climbing Mitchell’s High Peak . . . . . 513

- Signal-Station and “Mitchell’s Grave,” Summit of the Black Mountains . . . . . 514

- The Lookers-on at the Greenville Fair . . . . . 516

- Table Mountain, South Carolina . . . . . 518

- “Let us address de Almighty wid pra’r” . . . . . 520

- Mount Yonah, as seen from Clarksville, Georgia . . . . . 521

- The “Grand Chasm,” Tugaloo River, Northern Georgia . . . . . 522

- Toccoa Falls, Northern Georgia . . . . . 524

- A Mail-Carrier . . . . . 526

- Mission Ridge, near Chattanooga, Tennessee . . . . . 527

- Lookout Mountain, near Chattanooga, Tennessee . . . . . 529

- The Mineral Region in the vicinity of Chattanooga . . . . . 531

- Map showing Grades of Illiteracy in the United States. (From the U. S. Census Reports.) . . . . . 532

- Map of Middle Atlantic States, southern section, and North Carolina . . . . . 533

- The Rockwood Iron-Furnaces, Eastern Tennessee . . . . . 533

- The “John Ross House,” near Chattanooga. Residence of one of the old Cherokee Landholders . . . . . 534

- Catching a “Tarpin” . . . . . 535

- View from Lookout Mountain near Chattanooga . . . . . 536

- Umbrella Rock, on Lookout Mountain . . . . . 537

- Looking from “Lookout Cave” . . . . . 538

- “Rock City,” Lookout Mountain . . . . . 539

- View from Wood’s Redoubt, Chattanooga . . . . . 540

- On the Tennessee River, near Chattanooga . . . . . 542

- The “Suck,” on the Tennessee River . . . . . 543

- A Negro Cabin on the bank of the Tennessee . . . . . 544

- Knoxville, Tennessee . . . . . 546

- The East Tennessee University, Knoxville . . . . . 548

- At the ætna Coal Mines . . . . . 550

- “Down in a Coal Mine” . . . . . 551

- The old Market at Lynchburg . . . . . 552

- The James River, at Lynchburg, Virginia . . . . . 553

- A Side Street in Lynchburg, Virginia . . . . . 555

- Scene in a Lynchburg Tobacco Factory . . . . . 557

- “Down the steep hills every day come the country wagons” . . . . . 558

- Summoning Buyers to a Tobacco Sale . . . . . 560

- Evening on the James River–“The soft light which gently rested upon the lovely stream” . . . . . 561

- In the Gap of the Peaks of Otter, Virginia . . . . . 562

- The Summit of the Peak of Otter, Virginia . . . . . 564

- Blue Ridge Springs, South-western Virginia . . . . . 566

- Bristol, South-western Virginia . . . . . 569

- White Top Mountain, seen from Glade Springs . . . . . 570

- Making Salt, at Saltville, Virginia . . . . . 571

- Wayside Types–A Sketch from the Artist’s Virginia Sketch-Book . . . . . 573

- Wytheville, Virginia . . . . . 574

- Max Meadows, Virginia . . . . . 575

- The Roanoke Valley, Virginia . . . . . 576

- View near Salem, Virginia . . . . . 577

- View on the James River below Lynchburg . . . . . 578

- Appomattox Court-House–“It lies silently half-hidden in its groves and gardens” . . . . . 579

- “The hackmen who shriek in your ear as you arrive at the depot” . . . . . 581

- “The ‘Crater,’ the chasm created by the explosion of the mine which the Pennsylvanians sprung underneath Lee’s fortifications” . . . . . 582

- “The old cemetery, and ruined, ivy-mantled Blandford Church” . . . . . 583

- “Seen from a distance, Petersburg presents the appearance of a lovely forest pierced here and there by church spires and towers” . . . . . 585

- A Queer Cavalier . . . . . 587

- City Point, Virginia . . . . . 588

- A Peep into the Great Dismal Swamp . . . . . 589

- A Glimpse of Norfolk, Virginia . . . . . 591

- Map of the Virginia Peninsula . . . . . 593

- Hampton Roads . . . . . 594

- The Ruins of the old Church at Jamestown, Virginia . . . . . 621

- Statue of Lord Botetourt at Williamsburg, Virginia . . . . . 622

- The old Colonial Powder Magazine at Williamsburg, Virginia . . . . . 623

- The old Church of Bruton Parish–Williamsburg, Virginia . . . . . 624

- Cornwallis’s Cave, near Yorktown, Virginia . . . . . 624

- View of Richmond, Virginia, from the Manchester side of the James River . . . . . 626

- Libby Prison, Richmond, Virginia . . . . . 627

- Capitol Square, with a view of the Washington Monument, Richmond, Virginia . . . . . 628

- St. John’s Church, Richmond, Virginia . . . . . 629

- View on the James River, Richmond, Virginia. . . . . . 630

- Monument to the Confederate Dead, Richmond, Virginia . . . . . 631

- The Gallego Flouring-Mill, Richmond, Virginia . . . . . 631

- Scene on a Tobacco Plantation–Burning a Plant Patch . . . . . 632

- Tobacco Culture–Stringing the Primings . . . . . 633

- A Tobacco Barn in Virginia . . . . . 633

- The Old Method of Getting Tobacco to Market. . . . . . 634

- Getting a Tobacco Hogshead Ready for Market. . . . . . 635

- Scene on a Tobacco Plantation–Finding Tobacco Worms . . . . . 636

- The Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Virginia . . . . . 637

- A Water-melon Wagon . . . . . 646

- A Marl-bed on the Line of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad . . . . . 647

- Earthworks on the Chickahominy, near Richmond, Virginia . . . . . 648

- Scene at a Virginia “Corn-Shed” . . . . . 649

- Gordonsville, Virginia–“The negroes, who swarm day and night like bees about the trains” . . . . . 650

- The Tomb of Thomas Jefferson, at Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia . . . . . 651

- Monticello–The Old Home of Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence . . . . . 652

- The University of Virginia, at Charlottesville . . . . . 653

- A Water-melon Feast . . . . . 655

- Piedmont, from the Blue Ridge . . . . . 656

- View of Staunton, Virginia . . . . . 657

- Winchester, Virginia . . . . . 658

- Buffalo Gap and the Iron-Furnace . . . . . 659

- Elizabeth Iron-Furnace, Virginia . . . . . 660

- The Alum Spring, Rockbridge Alum Springs, Virginia . . . . . 661

- The Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia . . . . . 661

- Washington and Lee College, Lexington, Va. . . . . . 662

- Portrait of General Thomas J. Jackson, known as “Stonewall Jackson.” (From an engraving owned by M. Knoedler & Co., N. Y.) . . . . . 663

- General Robert Edward Lee, born January 19, 1801; died October 11, 1870 . . . . . 664

- The Great Natural Arch, Clifton Forge, Jackson’s River . . . . . 665

- Beaver Dam Falls . . . . . 665

- Falling Springs Falls, Virginia . . . . . 666

- Griffith’s Knob, and Cow Pasture River . . . . . 667

- Clay Cut, Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad . . . . . 668

- “Mac, the Pusher” . . . . . 668

- Jerry’s Run . . . . . 669

- Scene on the Greenbrier River in Western Virginia . . . . . 670

- The Hotel and Lawn at Greenbrier White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia . . . . . 671

- The Eastern Portal of Second Creek Tunnel, Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad . . . . . 672

- A Mountain Ride in a Stage-Coach . . . . . 673

- Anvil Rock, Greenbrier River . . . . . 675

- A West Virginia “Countryman” . . . . . 675

- A Freighters’ Camp, West Virginia . . . . . 676

- “The rude cabin built beneath the shadow of a huge rock” . . . . . 677

- “The rustic mill built of logs” . . . . . 678

- The Junction of Greenbrier and New Rivers . . . . . 678

- Descending the New River Rapids . . . . . 679

- A hard road for artists to travel . . . . . 680

- The “Hawk’s Nest,” from Boulder Point . . . . . 681

- Great Kanawha Falls . . . . . 682

- Miller’s Ferry, seen from the Hawk’s Nest . . . . . 682

- Richmond Falls, New River . . . . . 683

- Big Dowdy Falls, near New River . . . . . 684

- Whitcomb’s Bowlder . . . . . 685

- The Inclined Plane at Cannelton . . . . . 686

- Fern Spring Branch, a West Virginia Mountain Stream . . . . . 687

- Charleston, the West Virginia Capital . . . . . 688

- The Hale House, Charleston . . . . . 688

- Rafts of Saw-Logs on a West Virginia River . . . . . 689

- The Snow Hill Salt Works, on the Kanawha River . . . . . 690

- Indian Mound, near St. Albans . . . . . 690

- View of Huntington and the Ohio River . . . . . 691

- The result of climbing a sapling–An Artist in a Fix . . . . . 692

- The Levée at Louisville, Kentucky . . . . . 693

- A familiar scene in a Louisville Street . . . . . 695

- A Waiter at the Galt House, Louisville, Kentucky . . . . . 696

- Scene in the Louisville Exposition . . . . . 697

- Mammoth Cave, Kentucky–The Boat Ride on Echo River . . . . . 699

- The Entrance to Mammoth Cave (Looking Out). . . . . . 700

- Mammoth Cave–In “the Devil’s Arm-Chair” . . . . . 702

- The Mammoth Cave–“The Fat Man’s Misery”. . . . . . 703

- Mammoth Cave–“The Subterranean Album”. . . . . . 704

- A Country Blacksmith Shop . . . . . 706

- The Court-House, Louisville . . . . . 707

- The Cathedral, Louisville . . . . . 708

- The Post-Office, Louisville . . . . . 708

- The City Hall, Louisville . . . . . 709

- George D. Prentice. (From a Painting in the Louisville Public Library) . . . . . 710

- The Colored Normal School, Louisville . . . . . 710

- Louisville, Kentucky, on the Ohio River, from the New Albany Heights . . . . . 711

- Chimney Rock, Kentucky . . . . . 712

- Frankfort, on the Kentucky River . . . . . 713

- The Ascent to Frankfort Cemetery, Kentucky . . . . . 714

- The Monument to Daniel Boone in the Cemetery at Frankfort, Kentucky . . . . . 715

- View on the Kentucky River, near Frankfort . . . . . 719

- Asteroid Kicks Up . . . . . 717

- A Souvenir of Kentucky . . . . . 719

- A little Adventure by the Wayside . . . . . 720

- “Steady” . . . . . 725

- The Tennessee State Capitol, at Nashville . . . . . 726

- View from the State Capitol, Nashville, Tennessee . . . . . 727

- Tomb of Ex-President Polk, Nashville, Tennessee . . . . . 728

- The Hermitage–General Andrew Jackson’s old homestead, near Nashville, Tennessee . . . . . 729

- Young Tennesseans . . . . . 730

- The old home of Gen. Andrew Jackson, near Nashville . . . . . 731

- Tomb of Andrew Jackson, at the “Hermitage,” near Nashville . . . . . 732

- View from Federal Hill, Baltimore, Maryland, looking across the Basin . . . . . 733

- The Oldest House in Baltimore . . . . . 735

- Fort McHenry, Baltimore Harbor . . . . . 738

- Jones’s Falls, Baltimore . . . . . 740

- Exchange Place, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 741

- The Masonic Temple, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 742

- The Shot-Tower, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 742

- Scene on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal . . . . . 743

- The Blind Asylum, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 745

- The Eastern High School, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 746

- View of a Lake in Druid Hill Park, Baltimore . . . . . 747

- Maryland Institute, Baltimore . . . . . 748

- Woodberry, near Druid Hill Park . . . . . 749

- The new City Hall, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 750

- Lafayette Square, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 750

- The City Jail, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 752

- The Peabody Institute, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 753

- First Presbyterian Church, Baltimore . . . . . 754

- A Tunnel through the Alleghanies . . . . . 756

- Mount Vernon Square, with a view of the Washington Monument, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 758

- The Battle Monument, seen from Barnum’s Hotel, Baltimore . . . . . 759

- The Battle Monument, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 760

- The Cathedral, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 760

- The Wildey Monument, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 761

- Entrance to Druid Hill Park, Baltimore, Maryland . . . . . 761

- Scene on the Canal, near Harper’s Ferry . . . . . 762

- The Bridge at Harper’s Ferry . . . . . 763

- View of the Railroad and River, from the Mountains at Harper’s Ferry . . . . . 764

- Jefferson’s Rock, Harper’s Ferry . . . . . 769

- Cumberland Narrows and Mountains . . . . . 767

- Cumberland Viaduct, Maryland . . . . . 768

- Harper’s Ferry, Maryland . . . . . 769

- Old John Cupid, a Williamsburg Herb Doctor . . . . . 770

- Southern Types–Come to Market . . . . . 771

- Southern Types–A Southern Plough Team . . . . . 772

- Southern Types–Negro Boys Shelling Peas . . . . . 773

- Southern Types–A “likely Girl” with her Baby . . . . . 775

- Southern Types–Catching his Breakfast . . . . . 776

- Southern Types–Negro Shoeblacks . . . . . 777

- Southern Types–A Little Unpleasantness . . . . . 779

- Southern Types–“Going to Church” . . . . . 780

- Southern Types–A Negro Constable . . . . . 781

- Southern Types–The Wolf and the Lamb in Politics . . . . . 784

- Southern Types–Two Veterans discussing the Political Situation . . . . . 787

- The Potomac and Washington, seen from Arlington . . . . . 800

- Homeward Bound . . . . . 801

THE GREAT SOUTH.

I.

LOUISIANA PAST AND PRESENT.

Bienville, the Founder of New Orleans.

LOUISIANA to-day is Paradise Lost. In twenty years it may be Paradise Regained. It has unlimited, magnificent possibilities. Upon its bayou-penetrated soil, on its rich uplands and its vast prairies, a gigantic struggle is in progress. It is the battle of race with race, of the picturesque and unjust civilization of the past with the prosaic and leveling civilization of the present. For a century and a-half it was coveted by all nations; sought by those great colonizers of America,–the French, the English, the Spaniards. It has been in turn the plaything of monarchs and the bait of adventurers. Its history and tradition are leagued with all that was romantic in Europe and on the Western continent in the eighteenth century. From its immense limits outsprang the noble sisterhood of South-western States, whose inexhaustible domain affords an ample refuge for the poor of all the world.

A little more than half a century ago the frontier of Louisiana, with the Spanish internal provinces, extended nineteen hundred miles. The territory

boasted a sea-coast line of five hundred miles on the Pacific Ocean; drew a boundary line seventeen hundred miles along the edge of the British-American dominions; thence followed the Mississippi by a comparative course for fourteen hundred miles; fronted the Mexican Gulf for seven hundred miles, and embraced within its limits nearly one million five hundred thousand square miles. Texas was a fragment broken from it. California, Kansas, the Indian Territory, Missouri, and Mississippi, were made from it, and still there was an Empire to spare, watered by five of the finest rivers of the world. Indiana, Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, and Nebraska were born of it.

From French Bienville to America Claiborne the territorial administrations were dramatic, diplomatic, bathed in the atmosphere of conspiracy. Superstition cast a weird veil of mystery over the great rivers, and Indian legend peopled every nook and cranny of the section with fantastic creations of untutored fancy. The humble roof of the log cabin on the banks of the Mississippi covered all the grace and elegance of French society of Louis the Fourteenth’s time. Jesuit and Cavalier carried European thought to the Indians.

Frenchman and Spaniard, Canadian and Yankee, intrigued and planned on Louisiana soil with an energy and fierceness displayed nowhere else in our early history. What wonder, after this cosmopolitan record, that even the fragment of Louisiana which has retained the name–this remnant embracing but a thirtieth of the area of the original province–yet still covering more than forty thousand square miles of prairie, alluvial, and sea marsh–what wonder that it is so richly varied, so charming, so unique?

Six o’clock, on Saturday evening, in the good old city of New Orleans. From the tower of the Cathedral St. Louis the tremulous harmony of bells drifts lightly on the cool spring breeze, and hovers like a benediction over the antique buildings, the blossoms and hedges in the square, and the broad and swiftly-flowing river. The bells are calling all in the parish to offer masses for the repose of the soul of the Cathedral’s founder, Don Andre Almonaster, once upon a time “perpetual regidor” of New Orleans. Every Saturday eve, for three-quarters of a century, the solemn music from the Cathedral belfry has brought the good Andre to mind; and the mellow notes, as we hear them, seem to call up visions of the quaint past.

The Cathedral St. Louis–New Orleans.

Now the sunlight mingles with the breeze bewitchingly; the old square, the gray and red buildings with massive walls and encircling balconies, the great door of the new Cathedral, all are lighted up. See! a black-robed woman, with downcast eyes, passes silently over the holy threshold; a blind beggar, with a parti-colored handkerchief wound about his weather-beaten head, hears the rustling of her gown, and stretches out his trembling hand for alms;

a black girl looks wonderingly into the holy-water font; the market-women hush their chatter as they near the portal; a mulatto fruit-seller is lounging in the shade of an ancient arch, beneath the old Spanish Council House. This is not an American scene, and one almost persuades himself that he is in Europe, although ten minutes of rapid walking will bring him to streets and squares as generically American as any in Boston, Chicago, or St. Louis.

The Archbishop’s Palace–New Orleans.

Yonder is the archbishop’s palace: enter the street at one side of it, and you seem in a foreign land; in the avenue at the other you catch a glimpse of the rush and hurry of American traffic of to-day along the levée; you see the sharp-featured “river-hand,” hear his uncouth parlance, and recognize him for your countryman; you see huge piles of cotton bales; you hear the monotonous whistle of the gigantic white steamers arriving and departing; and the irrepressible negro slouches sullenly by with his hands in his pockets, and his cheeks distended with tobacco.

You must know much of the past of New Orleans and Louisiana to thoroughly understand their present. New England sprang from the Puritan mould; Louisiana from the French and Spanish civilizations of the eighteenth century. The one stands erect, vibrating with life and activity, austere and ambitious, upon its rocky shores; the other lies prone, its rich vitality dormant and passive, luxurious and unambitious, on the glorious shores of the tropic Gulf. The former was Anglo-Saxon and simple even to Spartan plainness at its outset; the latter was Franco-Spanish, subtle in the graces of the elder societies, self-indulgent and romantic at its beginning. And New Orleans was no more and no less the opposite of Boston in 1773 than a century later. It was a hardy rose which dared to blush, in the New England even of Governor Winthrop’s time,

before June had dowered the land with beauty; it was an o’er modest Choctaw rose in the Louisiana of De Soto’s epoch which did not shower its petals on the fragrant turf in February.

In Louisiana summer lingers long after the rude winter of the North has done its work of devastation; the sleeping passion of the climate only wakes now and then into the anger of lightning or the terrible tears of the thunder-storm; there are no chronic March horrors of deadly wind or transpiercing cold; the sun is kind; the days are radiant….

On the 14th of September, 1712, Louis the Magnificent granted to Anthony Crozat, a merchant prince, the Rothschild of the day, the exclusive privilege, for fifteen years, of trading in all the indefinitely bounded territory claimed by France as Louisiana.

Crozat obtained with his charter the additional privilege of sending a ship once a year for negroes to Africa, and of owning and working all the mines that might be discovered in the colony, provided that one-fourth of their proceeds should be reserved for the king. One ship-load of slaves to every two ship-loads of independent colonists was the proportion established for emigration to Louisiana more than a century and a half ago. Slavery was well begun. …

Let us look at the New Orleans of the period between 1723 and 1730. Imagine a low-lying swamp, overgrown with a dense ragged forest, cut up into a thousand miniature islands by ruts and pools filled with stagnant water. Fancy a small cleared space along the superb river channel, a space often inundated, but partially reclaimed from the circumambient swamp, and divided into a host of small correct squares, each exactly like its neighbor, and so ditched within and without as to render wandering after nightfall perilous.

The ditch which ran along the four sides of every square in the city was filled with a composite of black mud and refuse, which, under a burning sun, sent forth a deadly odor. Around the city was a palisade and a gigantic moat; tall grasses grew up to the doors of the houses, and the hoarse chant of myriads of frogs mingled with the vesper songs of the colonists. Away where the waters of the Mississippi and of Lake Pontchartrain had formed a high ridge of land, was the “Leper’s Bluff;” and among the reeds from the city thitherward always lurked a host of criminals.

The negro, fresh from the African coast, then strode defiantly along the low shores by the stream; he had not learned the crouching, abject gait which a century of slavery afterwards gave him. He was punished if he rebelled; but he kept his dignity. In the humble dwellings which occupied the squares there were noble manners and graces; all the traditions and each finesse of the time had not been forgotten in the voyage from France: and airy gentlemen

and stately dames promenaded in this queer, swamp-surrounded, river-endangered fortress, with Parisian grace and ease.

There were few churches, and the colonists gathered about great wooden crosses in the open air for the ceremonials of their religion There were twice as many negroes as white people in the city. Domestic animals were so scarce that he who injured or fatally wounded a horse or a cow was punished with death. Ursuline nuns and Jesuit fathers glided about the streets upon their scared missions. The principal avenues within the fortified enclosure were named after princes of the royal blood–Maine, Condé, Conti, Toulouse, and Bourbon; Chartres street took its name from that of the son of the regent of Orleans, and an avenue was named in honor of Governor Bienville.

Along the river, for many miles beyond the city, marquises and other noble representatives of aristocratic French families had established plantations, and lived luxurious lives of self-indulgence, without especially contributing to the wealth of the colony. Jews were banished from the bounds of Louisiana. Sundays and holidays were strictly observed, and negroes found working on Sunday were confiscated. No worship save the Catholic was allowed; white subjects were forbidden to marry or to live in concubinage with slaves, and masters were not allowed to force their slaves into any marriage against their will; the children of a negro slave-husband and a negro free-wife were all free; if the mother was a slave and the husband was free, the children shared the condition of the mother.

Slaves were forbidden to gather in crowds, by day or night, under any pretext, and if found assembled, were punished by the whip, or branded with the mark of the flower-de-luce, or executed. The slaves all wore marks or badges, and were not permitted to sell produce of any kind without the written consent of their masters. The protection and security of slaves in old age was well provided for; Christian negroes were permitted burial in consecrated ground. The slave who produced a bruise, or the “shedding of blood in the face,” on the person of his master, or any of the family to which he appertained, by striking them, was condemned to death; and the runaway slave, when caught, after the first offence, had his ears cut off, and was branded; after the second, was hamstrung and again branded; after the third, was condemned to death. Slaves who had been set free were still bound to show the profoundest respect to their “former masters, their widows and children,” under pain of severe penalties. Slave husbands and wives were not permitted to be seized and sold separately when belonging to the same master; and whenever slaves were appointed tutors to their masters’ children, they “were held and regarded as being thereby set free to all intents and purposes.”

The Choctaws and Chickasaws, neighbors to the colonists, were waging destructive war against each other; hurricanes regularly destroyed all the engineering works erected by the French Government at the mouths of the Mississippi; and expeditions against the Natchez and the Chickasaws, arrivals of ships from France with loads of troops, provisions, and wives for the colonists, the building of levées along the river front near New Orleans, and the

occasional deposition from and re-instatement in office of Bienville, were the chief events in those crude days of the beginning. …

New Orleans from 1792 to 1797? Its civilization has changed; it is fitted into the iron groove of Spanish domination, and has become bigoted, narrow, and hostile to innovation. …

The priests and friars are half-mad with despair because the mixed population pays so very little attention to its salvation from eternal damnation, and because the roystering officers and soldiers of the regiment of Louisiana admit that they have not been to mass for three years. The French hover about the few taverns and coffee-houses permitted in the city, and mutter rebellion against the Spaniard, whom they have always disliked. The Spanish and French schools are in perpetual collision; so are the manners, customs, diets, and languages of the respective nations. The Ursuline convent has refused to admit Spanish women who desire to become nuns, unless they learn the French language; and the ruling Governor, Baron Carondelet, has such small faith in the loyalty of the colonists that he has had the fortifications constructed with a view not only to protecting himself against attacks from without, but from within.

The city has suddenly taken on a wonderful aspect of barrack-yard and camp. On the side fronting the Mississippi are two small forts commanding the road and the river. On their strong and solid brick-coated parapets, Spanish sentinels are languidly pacing; and cannon look out ominously over the walls. Between these two forts, and so arranged as to cross its fires with them, fronting on the main street of the town, is a great battery commanding the river. Then there are forts at each of the salient angles of the long square forming the city, and a third a little beyond them–all armed with eight guns each. From one of these tiny forts to another, noisy dragoons are always clattering; officers are parading to and fro; government officials block the way; and the whole town looks like a Spanish garrison gradually growing, by some mysterious process of transformation, into a French city.

II.

THE FRENCH QUARTER OF NEW ORLEANS–THE REVOLUTION AND ITS EFFECTS.

LET me show you some pictures from the New Orleans of to-day. The nightmare of civil war has passed away, leaving the memory of visions which it is not my province–certainly not my wish–to renew. The Crescent City has grown so that Claiborne and Jackson could no longer recognize it. It was gaining immensely in wealth and population until the social and political revolutions following the war came with their terrible, crushing weight, and the work of re-establishing the commerce of the State has gone on under conditions most disheartening and depressing; though trial seems to have brought out a reserve of energy of which its possessors had never suspected themselves capable.

Step off from Canal street, that avenue of compromises which separates the French and the American quarters, some bright February morning, and you will at once find yourself in a foreign atmosphere. A walk into the French section enchants you; the characteristics of an American city vanish; this might be Toulouse, or Bordeaux, or Marseilles! The houses are all of stone or brick, stuccoed or painted; the windows of each story descend to the floors, opening, like doors, upon airy, pretty balconies, protected by iron railings; quaint dormer windows peer from the great roofs; the street doors are massive, and large enough to admit carriages into the stone-paved court-yards, from which stairways communicate with the upper apartments.

Sometimes, through a portal opened by a slender, dark-haired, bright-eyed Creole girl in black, you catch a glimpse of a garden, delicious with daintiest blossoms, purple and red and white gleaming from vines clambering along a gray wall; rose-bushes, with the grass about them strewn with petals; bosquets, green and symmetrical; luxuriant hedges, arbors, and refuges, trimmed by skillful hands; banks of verbenas; bewitching profusion of peach and apple blossoms; the dark green of the magnolia; in a quiet corner, the rich glow of the orange in its nest among the thick leaves of its parent tree; the palmetto, the catalpa;–a mass of bloom which laps the senses in slumbrous delight. Suddenly the door closes, and your paradise is lost, while Eve remains inside the gate!

From the balconies hang, idly flapping in the breeze, little painted tin placards, announcing “Furnished apartments to rent!” Alas! in too many of the old mansions you are ushered by a gray-faced woman clad in deepest black, with little children clinging jealously to her skirts, and you instinctively

note by her manners and her speech that she did not rent rooms before the war. You pity her, and think of the multitudes of these gray-faced women; of the numbers of these silent, almost desolate houses.

Now and then, too, a knock at the porter’s lodge will bring to your view a bustling Creole dame, fat and fifty, redolent of garlic and new wine, and robust in voice as in person. How cheerily she retails her misfortunes, as if they were blessings! “An invalid husband–voyez-vous ça! Auguste a Confederate, of course–and is yet; but the pauvre garçon is unable to work, and we are very poor!” All this merrily, and in high key, while the young negress–the housemaid–stands lazily listening to her mistress’s French, nervously polishing with her huge lips the handle of the broom she holds in her broad, corded hands.

Business here, as in foreign cities, has usurped only half the domain; the shopkeepers live over their shops, and communicate to their commerce somewhat of the aroma of home. The dainty salon, where the ladies’ hairdresser holds sway, has its doorway enlivened by the baby; the grocer and his wife, the milliner and his daughter, are behind the counters in their respective shops. Here you pass a little café, with the awning drawn down, and, peering in, can distinguish half-a-dozen bald, rotund old boys drinking their evening absinthe, and playing picquet and vingt-et-un, exactly as in France.

“A lazy negro, recumbent in a cart.”

Here, perhaps, is a touch of Americanism: a lazy negro, recumbent in a cart, with his eyes languidly closed, and one dirty foot sprawled on the sidewalk. No! even he responds to your question in French, which he speaks poorly though fluently French signs abound; there is a warehouse for wines and brandies from the heart of Southern France; here is a funeral notice, printed in deepest black: “The friends of Jean Baptiste,” etc., “are respectfully invited to be present at the funeral, which will take place at precisely four o’clock, on the –.” The notice is on black-edged note-paper, nailed to a post. Here pass a group of French negroes, the buxom girls dressed with a certain grace, and with gayly-colored handkerchiefs wound about an unpardonable luxuriance of wool. Their cavaliers are clothed mainly in antiquated garments rapidly approaching the level of rags; and their patois resounds for half-a-dozen blocks.

Turning into a side street leading off from Royal, or Chartres, or Bourgogne, or Dauphin, or Rampart streets, you come upon an odd little shop, where the cobbler sits at his work in the shadow of a grand old Spanish arch; or upon a nest of curly-headed negro babies ensconced on a tailor’s bench at the window of a fine ancient mansion; or you look into a narrow room, glass-fronted, and see a long and well-spread table, surrounded by twenty Frenchmen and Frenchwomen, all talking at once over their eleven o’clock breakfast.

Or you may enter aristocratic restaurants, where the immaculate floors are only surpassed in cleanliness by the spotless linen of the tables; where a

solemn dignity, as befits the refined pleasure of dinner, prevails, and where the waiter gives you the names of the dishes in both languages, and bestows on you a napkin large enough to serve you as a shroud, if this strange melange of French and Southern cookery should give you a fatal indigestion. The French families of position usually dine at four, as the theatre begins promptly at seven, both on Sundays and week days. There is the play-bill, in French, of course; and there are the typical Creole ladies, stopping for a moment to glance at it as they wend their way shopward. For it is the shopping hour; from eleven to two the streets of the old quarter are alive with elegantly, yet soberly attired ladies, always in couples, as French etiquette exacts that the unmarried lady shall never promenade without her maid or her mother.

One sees beautiful faces on the Rue Royale (Royal street), and in the balconies and lodges of the Opera House; sometimes, too, in the cool of the evening, there are fascinating little groups of the daughters of Creoles on the balconies, gayly chatting while the veil of the twilight is torn away, and the glory of the Southern moonlight is showered over the quiet streets.

The Creole ladies are not, as a rule, so highly educated as the gracious daughters of the “American quarter;” but they have an indefinable grace, a savoir in dress, and a piquant and alluring charm in person and conversation, which makes them universal favorites in society.

One of the chiefest of their attractions is the staccato and queerly-colored English, really French in idea and accent, which many of them speak. At the Saturday matinées, in the opera or comedy season at the French Theatre, you will see hundreds of the ladies of “the quarter;” and rarely can a finer grouping of lovely brunettes be found; nowhere a more tastefully-dressed and elegantly-mannered assembly.

“The negro nurses stroll on the sidewalks, chattering in quaint French to the little children.”

The quiet which has reigned in the old French section since the war ended is, perhaps, abnormal; but it would be difficult to find village streets more tranquil than are the main avenues of this foreign quarter after nine at night. The long, splendid stretches of Rampart and Esplanade streets, with their rows of trees planted in the centre of the driveways,–the whitewashed trunks giving a fine effect of green and white,–are peaceful; the negro-nurses stroll on the sidewalks, chattering in quaint French to the little children of their former masters–now their “employers.”

There is no attempt on the part of the French or Spanish families to inaugurate style and fashion in the city; quiet home society, match-making and marrying of

daughters, games and dinner parties, church, shopping, and calls in simple and unaffected manner, content them.

The majority of the people in the whole quarter seem to have a total disregard of the outside world, and when one hears them discussing the distracted condition of local politics, one can almost fancy them gossiping on matters entirely foreign to them, instead of on those vitally connected with their lives and property. They live very much among themselves. French by nature and training, they get but a faint reflection of the excitements in these United States. It is also astonishing to see how little the ordinary American citizen of New Orleans knows of his French neighbors; how ill he appreciates them. It is hard for him to talk five minutes about them without saying, “Well, we have a non-progressive element here; it will not be converted.” Having said which, he will perhaps paint in glowing colors the virtues and excellences of his French neighbors, though he cannot forgive them for taking so little interest in public affairs.

“The interior garden, with its curious shrine.”

Here we are again at the Archbishop’s Palace, once the home of the Ursuline nuns, who now have, further down the river, a splendid new convent and school, surrounded by beautiful gardens. This ancient edifice was completed by the French Government in 1733, and is the oldest in Louisiana. Its Tuscan composite architecture, its porter’s lodge, and its interior garden with its curious shrine, make it well worth preserving, even when the tide of progress shall have reached this nook on Condé street. The Ursuline nuns occupied this site for nearly a century, and it was abandoned by them only because they were tempted, by the great rise in real estate in that vicinity, to sell. The new convent is richly endowed, and is one of the best seminaries in the South.

Many of the owners of property in the vicinity of the Archbishop’s Palace have removed to France, since the war,–doing nothing for the benefit of the metropolis which gave them their fortunes. The rent of these solidly-constructed old houses once brought them a sum which, when translated from dollars into francs, was colossal, and which the Parisian tradesmen tucked away into their strong boxes. Now they get almost nothing; the houses are mainly vacant. With the downfall of slavery, and the advent of reconstruction, came such radical changes in Louisiana politics and society that those belonging to the ancien régime who could flee, fled; and a prominent historian and gentleman

of most honorable Creole descent told me that, among his immense acquaintance, he did not know a single person who would not leave the State if means were at hand.

The grooves in which society in Louisiana and New Orleans had run before

The New Ursuline Convent–New Orleans.

the late struggle were so broken that even a residence in the State was distasteful to him and the society he represented; since the late war, he said, 500 years seemed to have passed over the common-wealth. The Italy of Augustus was not more dissimilar to the Italy of to-day than is the Louisiana of to-day to the Louisiana before the war. There was no longer the spirit to maintain the grand, unbounded hospitality once so characteristic of the South. Formerly, the guest would have been presented to planters who would have entertained him for days, in royal style, and who would have sent him forward in their own carriages, commended to the hospitality of their neighbors. Now these same planters were living upon corn and pork. “Most of these people,” said the gentleman, “have vanished from their homes; and I actually know ladies of culture and refinement, whose incomes were gigantic before the war, who are ‘washing’ for their daily bread. The misery, the despair, in hundreds of cases, are beyond belief.”

“Many lovely plantations,” said he, “are entirely deserted; the negroes will not remain upon them, but flock into the cities, or work on land which they have purchased for themselves.” He would not believe that the free negro did as much work for himself as he formerly did for his master. He considered the labor system at the present time terribly onerous for planters. The negroes were only profitable as field hands when they worked on shares, the planters furnishing them land, tools, horses, mules, and advancing them food. He said that he would not himself hire a negro even at small wages; he did not believe it would be profitable. The discouragement of the natives of Louisiana, he believed, arose in large degree from the difficulty of obtaining capital with which to begin anew. He knew instances where only $10,000 or $20,000 were needed for the improvement of water power, or of lands which would net hundreds of thousands. He had himself written repeatedly, urging people at the North to invest, but they would not, and alleged that they should not alter their determination so long as the present political condition prevailed.

He added, with great emphasis, that he did not think the people of the North would believe a statement which should give a faithful transcript of the present condition of affairs in Louisiana. The natives of the State could hardly

realize it themselves; and it was not to be expected that strangers, of differing habits of life and thought, should do it. He did not blame the negro for his present incapacity, as he considered the black man an inferior being, peculiarly unfitted by ages of special training for what he was now called upon to undertake. The negro was, he thought, by nature, kindly, generous, courteous, susceptible of civilization only to a certain degree; devoid of moral consciousness, and usually, of course, ignorant. Not one out of a hundred, the whole State through, could write his name; and there had been fifty-five in one single Legislature who could neither read nor write. There was, according to him, scarcely a single man of color in the last Legislature who was competent in any large degree.

The Louisiana white people were in such terror of the negro government that they would rather accept any other despotism. A military dictator would be far preferable to them; they would go anywhere to escape the ignominy to which they were at present subjected. The crisis was demoralizing every one. Nobody worked with a will; every one was in debt. There was not a single piece of property in the city of New Orleans in which he would at present invest, although one could now buy for $5,000 or $10,000 property originally worth $50,000. He said it would not pay to purchase, the taxes were so enormous. The majority of the great plantations had been deserted on account of the excessive taxation. Only those familiar with the real causes of the despair could imagine how deep it was.

Benefit by immigration, he maintained, was impossible under the present régime. New-comers mingled in the distracted politics in such a manner as to neglect the development of the country. Thousands of the citizens were fleeing to Texas (and I could vouch for the correctness of that assertion). He said that the mass of immigrants became easily discouraged and broken down, because they began by working harder than the climate would permit.

In some instances, Germans on coming into the State had been ordered by organizations both of white and colored native workmen not to labor so much daily, as they were setting a dangerous example! Still, he believed that almost any white man would do as much work as three negroes. He hardly thought that in fifty years there would be any negroes in Louisiana. The race was rapidly diminishing. Planters who had owned three or four hundred slaves before the war, had kept a record of their movements, and found that more than half of them had died of want and neglect. The negroes did not know how to care for themselves. The women now on the same plantations where they had been owned as slaves gave birth to only one child where they had previously borne three. They would not bear children as of old; the negro population was rapidly decreasing. Gardening, he said, had proved an unprofitable experiment, because of the thievish propensities of the negro. All the potatoes, turnips, and cabbages consumed by the white people of New Orleans came from the West.

Such was the testimony of one who, although by no means unfair or bitterly partisan, perhaps allowed his discouragement to color all his views. He frankly

accepted the results of the war, so far as the abolition of slavery and the consequent ruin of his own and thousands of other fortunes were concerned; he has, indeed, borne with all the evils which have arisen out of reconstruction, without murmuring until now, when he and thousands of his fellows are pushed to the wall. He is the representative of a very large class; the discouragement is no dream. It is written on the faces of the citizens; you may read and realize it there.

Ah! these faces, these faces;–expressing deeper pain, profounder discontent than were caused by the iron fate of the few years of the war! One sees them everywhere; on the street, at the theatre, in the salon, in the cars; and pauses for a moment, struck with the expression of entire despair–of complete helplessness, which has possessed their features. Sometimes the owners of the faces are one-armed and otherwise crippled; sometimes they bear no wounds or marks of wounds, and are in the prime and fullness of life; but the look is there still. Now and then it is controlled by a noble will, the pain of which it tells having been trampled under the feet of a great energy; but it is always there. The struggle is over, peace has been declared, but a generation has been doomed. The past has given to the future the dower of the present; there seems only a dead level of uninspiring struggle for those going out, and but small hope for those coming in. That is what the faces say; that is the burden of their sadness.

These are not of the loud-mouthed and bitter opponents of everything tending to reconsolidate the Union; these are not they who will tell you that some day the South will be united once more, and will rise in strength and strike a blow for freedom; but they are the payers of the price. The look is on the faces of the men who wore the swords of generals who led in disastrous measures; on the faces of women who have lost husbands, children, lovers, fortunes, homes, and comfort for evermore. The look is on the faces of the strong fighters, thinkers, and controllers of the Southern mind and heart; and here in Louisiana it will not brighten, because the wearers know that the great evils of disorganized labor, impoverished society, scattered families, race legislation, retributive tyranny and terrorism, with the power, like Nemesis of old, to wither and blast, leave no hope for this generation. Heaven have mercy on them! Their fate is too utterly inevitable not to command the strongest sympathy.