I moved to Water Valley, MS, about 4 months ago, and since I came here, I have been busy creating some of the content for my upcoming memoir book: Churches in the Wildwood.

As the title might suggest, my research for that book has taken me not only to the rural areas of Mississippi, but it has also carried me back in time. I have interviewed many people around Water Valley, and now, I am consulting the resources of local historical museums. In exchange for their resources, I have committed my time to two of those museums.

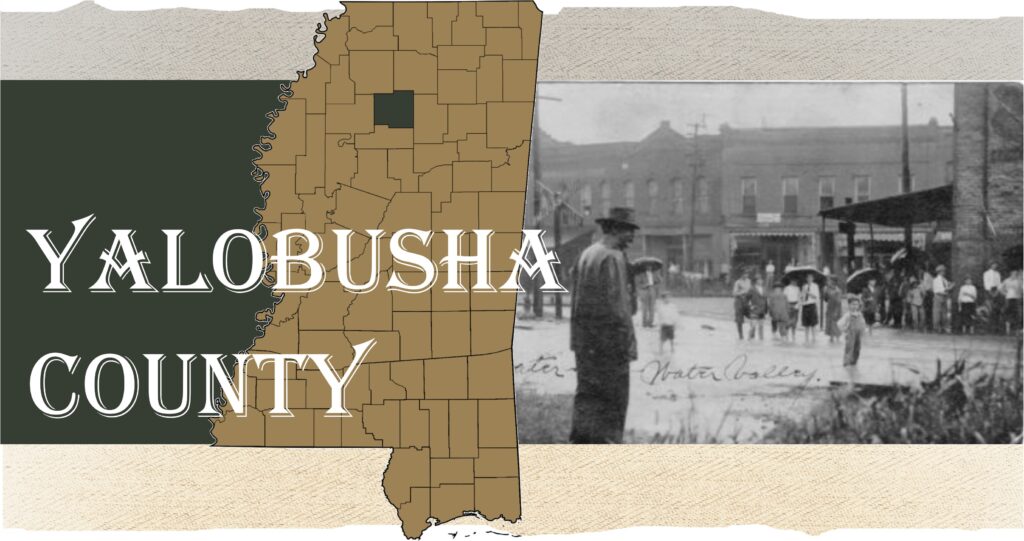

On September 17, 2023, I attended my first meeting of the Yalobusha County Historical Society.

The week prior to that, I also obligated myself to help with the archives of the Water Valley Casey Jones Railroad Museum. In this post, I am sharing some of my research for that organization.

A railroad man Bruce Gurner was also a prominent historian who lived in Water Valley, and Bruce left the Casey Jones Museum with a vast amount of information about Water Valley’s train history. With the assistance of Thompson Studios, Bruce recorded several historical videos. My first assignment for the Casey Jones Museum was to watch those videos and write a summary of what Bruce covers in several of them. I thought that some of you might enjoy being part of that process.

Tales of the Rails Part 1: Dedicated to the Railroaders of the Mississippi Division

Illinois Central Railroad Central Route – Mississippi Valley

Tales of the Rails Part 1: The Railroad Comes to Mississippi

When people migrated to Mississippi and began to farm, they needed a way to move their crops to markets.

The area around Water Valley populated quickly. In the census of 1840, there were 12,000 people in this area.

At that time, cotton was the primary farm product here. Cotton Was King.

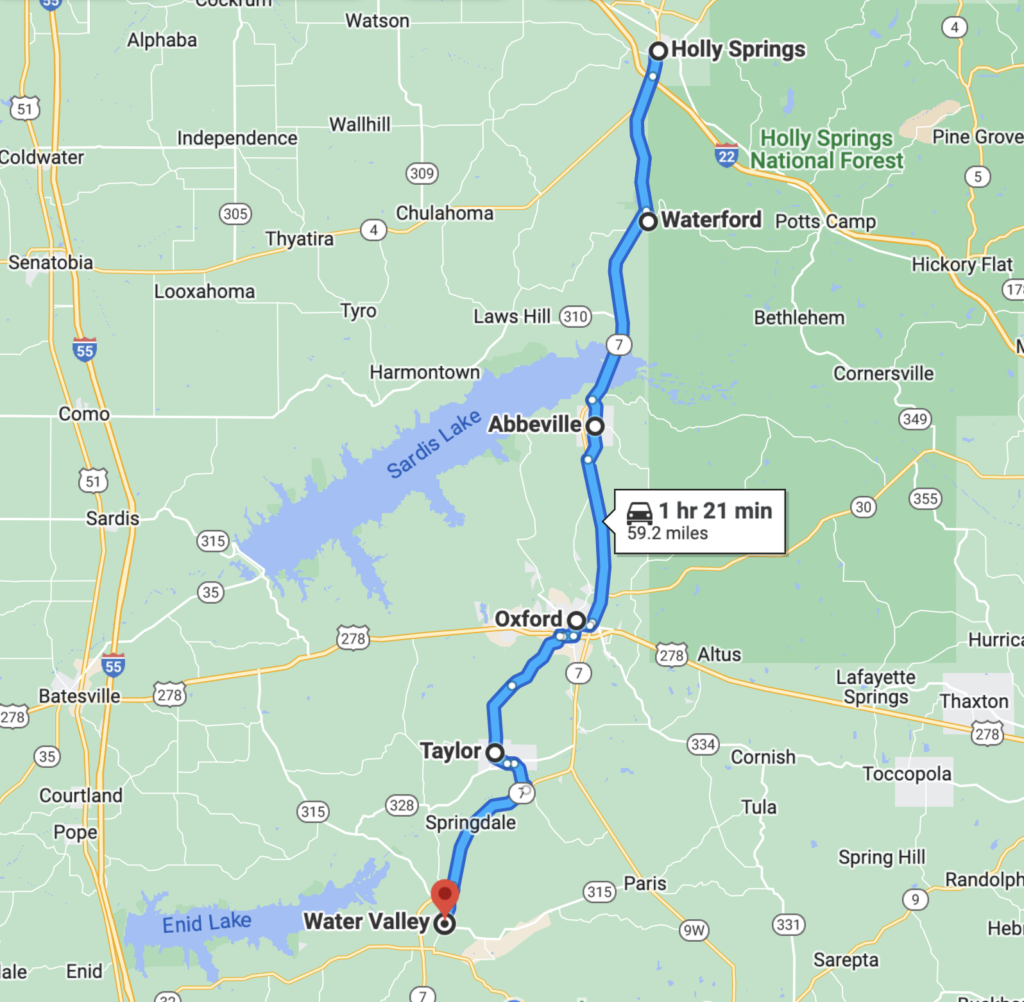

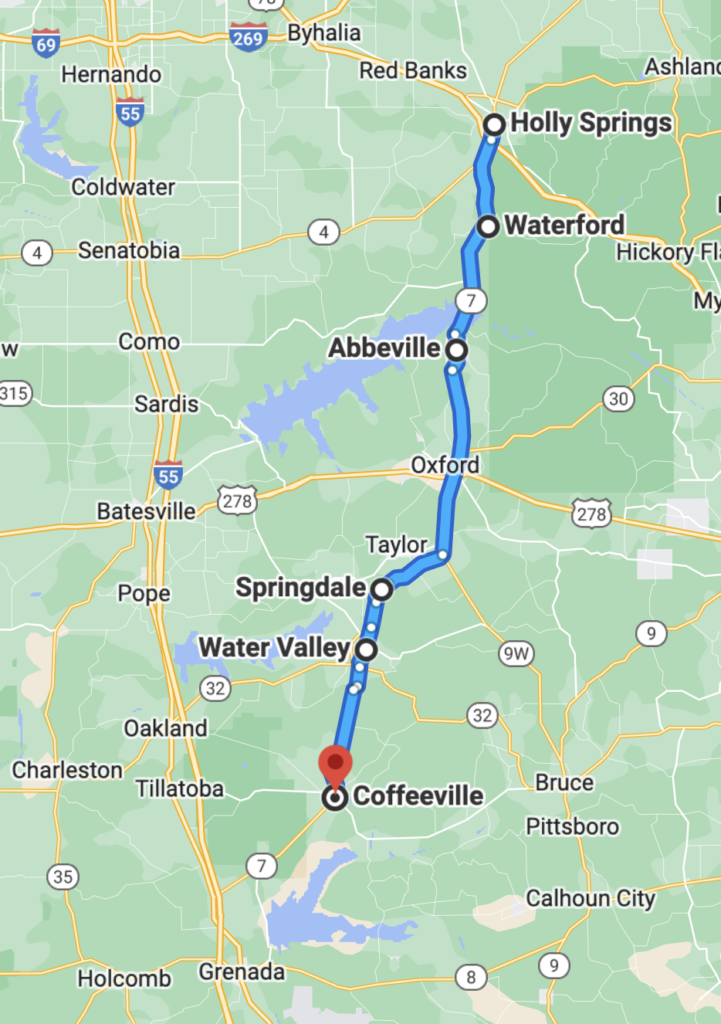

For the purpose of transporting cotton, The Mississippi Central Railroad started in Holly Springs. Not close to the Mississippi River, that area was isolated from its markets. The building of that railroad line began in 1853.

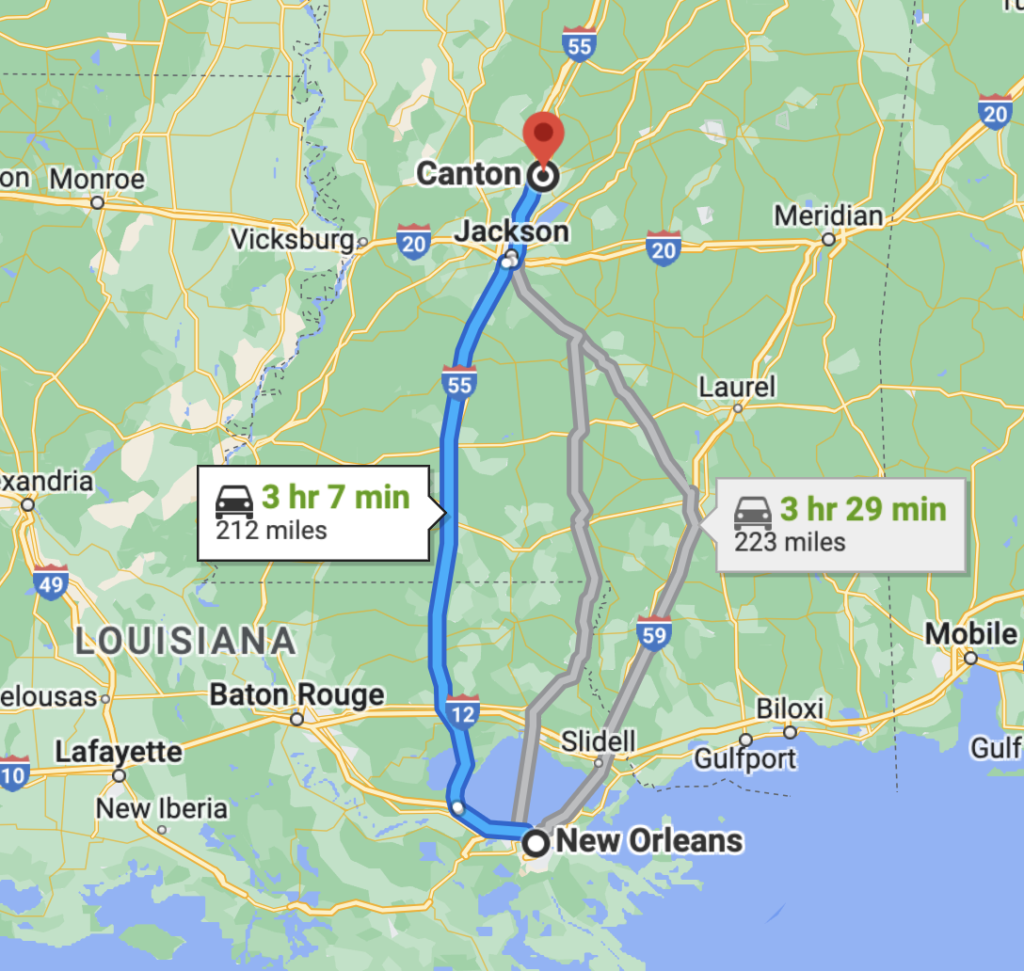

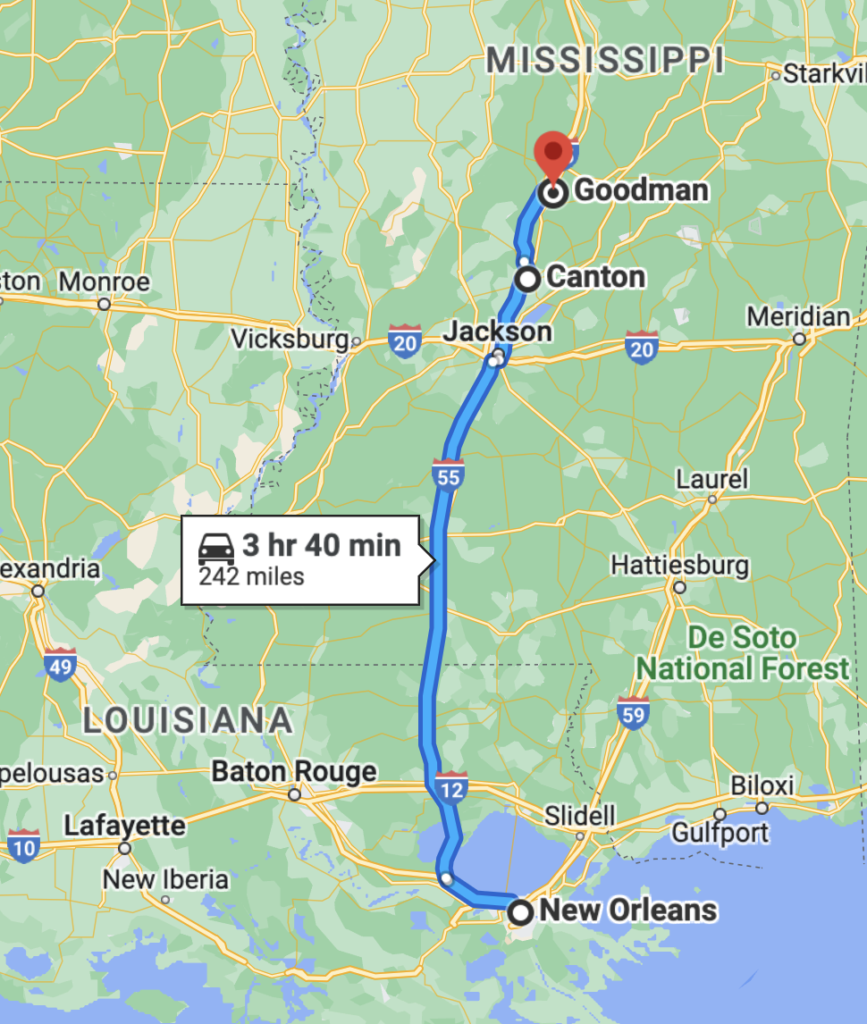

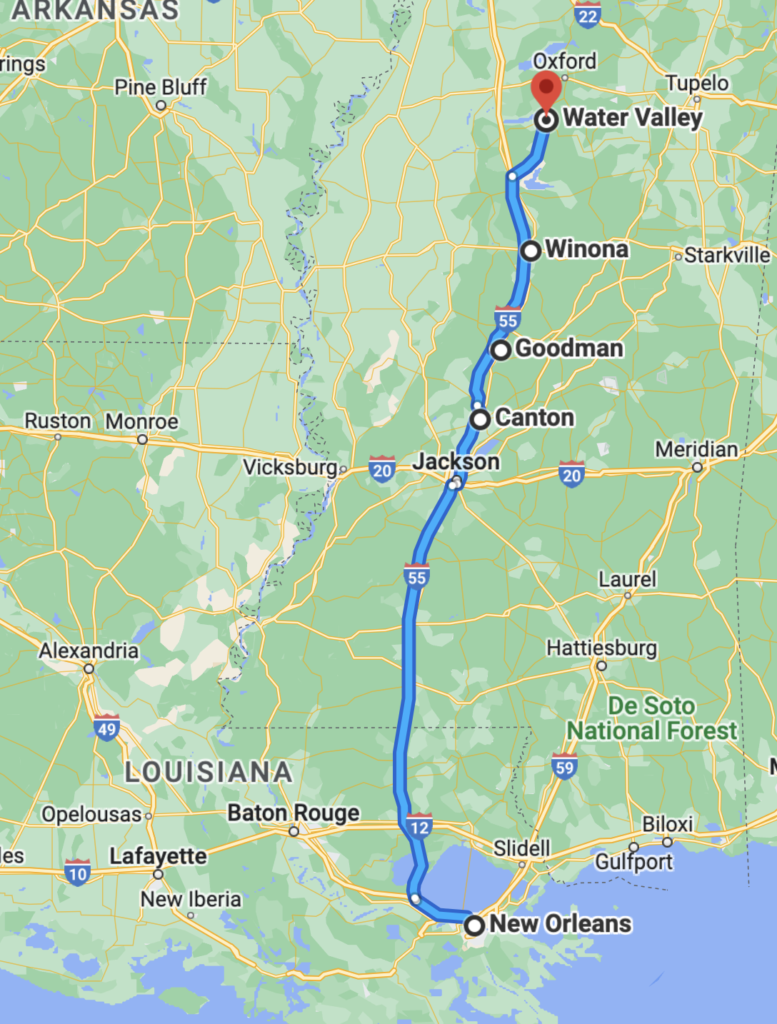

Almost simultaneously, another train line, the New Orleans Jackson and Great Northern Railroad was built and it ran from New Orleans, LA, to Canton, MS.

Ultimately, the Mississippi Central Railroad ran from Canton through Water Valley up to the Tennessee State Line.

The area of the railroad from the Tennessee State Line up to Jackson, TN was named the Mississippi Central and Tennessee Railroad.

By 1858, the railroad was completed from New Orleans up to Canton. To celebrate that success, a flat car was attached to the front of a train and a cannon was mounted to the top of that car. As they traveled along their victory ride, the railroad crew shot a cannon every couple of miles. Although they did not reach the Canton destination until about 11 pm that night, they had a barbecue and a big dance or ball when they arrived.

The other line was traveling from Holly Springs toward Grenada.

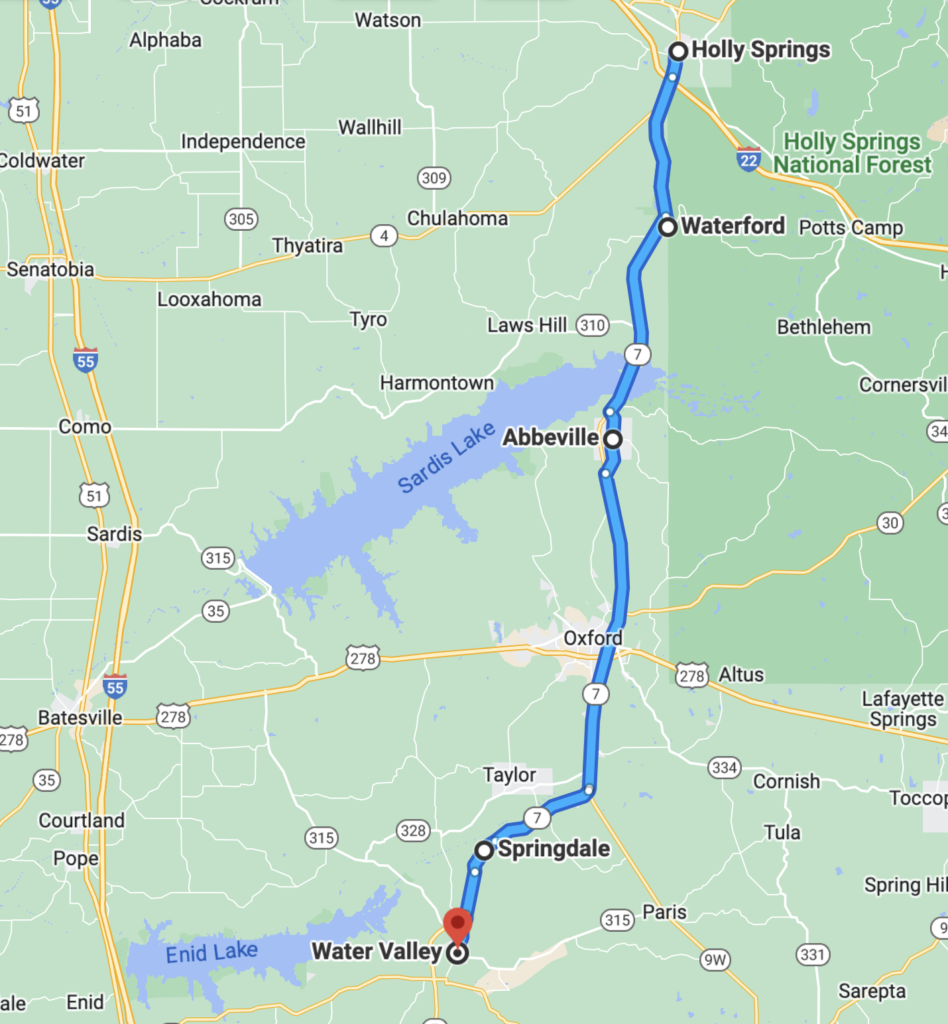

Initially, that route went from Holly Springs to Waterford to Abbeville to Oxford to Taylor. Because there were not enough rails to finish, that line was temporarily paused 3 miles north of Water Valley.

At the same time, the Canton line was extended to Goodman, a town that was named for Walter Goodman.

Part 2: The Railroad Makes it to Water Valley.

Because funds were needed to complete the railroad line, Walter Goodman traveled to England to borrow money, and he met with George Peabody, a financier.

“George Peabody (February 18, 1795 – November 4, 1869) was an American financier and philanthropist. He is oft-considered the father of modern philanthropy.

“Born into a poor family in Massachusetts, Peabody went into business in dry goods and later into banking. In 1837 he moved to London (which was then the capital of world finance) where he became the most noted American banker and helped to establish the young country’s international credit.” Wikipedia

“The original Peabody Hotel was built in 1869 at the corner of Main and Monroe by Robert Campbell Brinkley, who named it to honor George Peabody for his contributions to the South.” The Commercial Appeal

Peabody loaned the money needed, and the railroad construction began again—from Goodman, northward and from Water Valley, southward. The day the 2 sections of rails met in Winona, 5,000 people gathered to celebrate that momentous occasion. The railroad had been completed from New Orleans to Water Valley, but the Civil War soon began and destroyed the rails. Yet, the line had been established.

The day the 2 sections of rails met in Winona, 5,000 people gathered to celebrate that momentous occasion. The railroad had been completed from New Orleans to Water Valley, but the Civil War soon began and destroyed the rails. Yet, the line had been established.

When the railroad was destroyed, the farmers in the Holly Springs area had to transport their cotton by wagons, but farmers more westward were able to use the river for shipping. Because the Mississippi River flowed to New Orleans, it became vitally important. In order to sell the cotton, it had to be shipped to brokers there.

The New Orleans Cotton Exchange grew out of the South’s need to have brokers who sold their cotton globally.

“The building known as the New Orleans Cotton Exchange (constructed in 1921) on the corner of Carondelet and Gravier streets marks what was once among the most influential spots in the South, an area called “the cotton district,” or “the Wall Street of New Orleans.” It traced its origins to a series of technical breakthroughs on both sides of the Atlantic in the late 1700s. On the demand side, in England, the steam engine, mechanical spinners and the power loom drastically reduced production costs, which lowered the price and increased demand for manufactured fabric. On the supply side, in the United States, the introduction of Sea Island cotton and upland varieties expanded the plant’s growing range, while Eli Whitney’s “cotton engine,” or gin (1793) enabled a ten-fold savings of time to remove seeds and debris from lint. With cotton poised to boom, settlers from the Atlantic seaboard migrated to the lower Mississippi Valley, which, along with the key transshipment port of New Orleans, were now under American dominion, thanks to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

“Cotton plantations were soon established throughout the rich bottomlands and loess bluffs between Baton Rouge and Natchez, served by an ever-growing armada of yet another technological advancement: shallow-draft paddle-wheel steamboats. Within a few years, cotton rose from a minor regional crop to a major export. The two million pounds of cotton raised in Louisiana in 1811 quintupled in 10 years, which in turn nearly quadrupled, to 38 million pounds, in 1826. By 1834, the harvest was over 62 million pounds. For decades to come, New Orleans would serve as a key node in the Cotton Triangle, where Northern-owned ships would ferry cotton to ports like Liverpool, proceed to New York or other Northeastern cities with cargos of fabric, and return to New Orleans with Northern manufactured goods.

The ornate Cotton Exchange opened in 1883 on Carondelet at Gravier, is seen here in 1900. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

. . .

“Edward King described a typical day in the cotton district in his 1875 book, The Great South. ‘Cotton is the only subject spoken of; the pavements [by] the Exchange are crowded with smartly-dressed gentlemen, who eagerly discuss crops and values, and who have a perfect mania for [cotton], each worshipping at the shrine of the same god. From high noon until dark the planter, the factor [and] the speculator flit feverishly to and from the portals of the Exchange, and nothing can be heard above the excited hum [but] the sharp voice…reading the latest telegrams.’ https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/king/king.html

Campanella, Richard. “The New Orleans Cotton Exchange, 1871-1964 | Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans.” Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans, 11 Feb. 2018, prcno.org/new-orleans-cotton-exchange.

Part 3: The Civil War

The Railroad was Very Important During the Civil War

Water Valley boys reported to training for the Civil War by traveling on the Mississippi Central Railroad or the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. They traveled to Corinth for their training program.

As the war continued, the railroad became a source of great conflict.

When Water Valley was captured in 1862, it was because Grant needed to get down to Vicksburg and capture it.

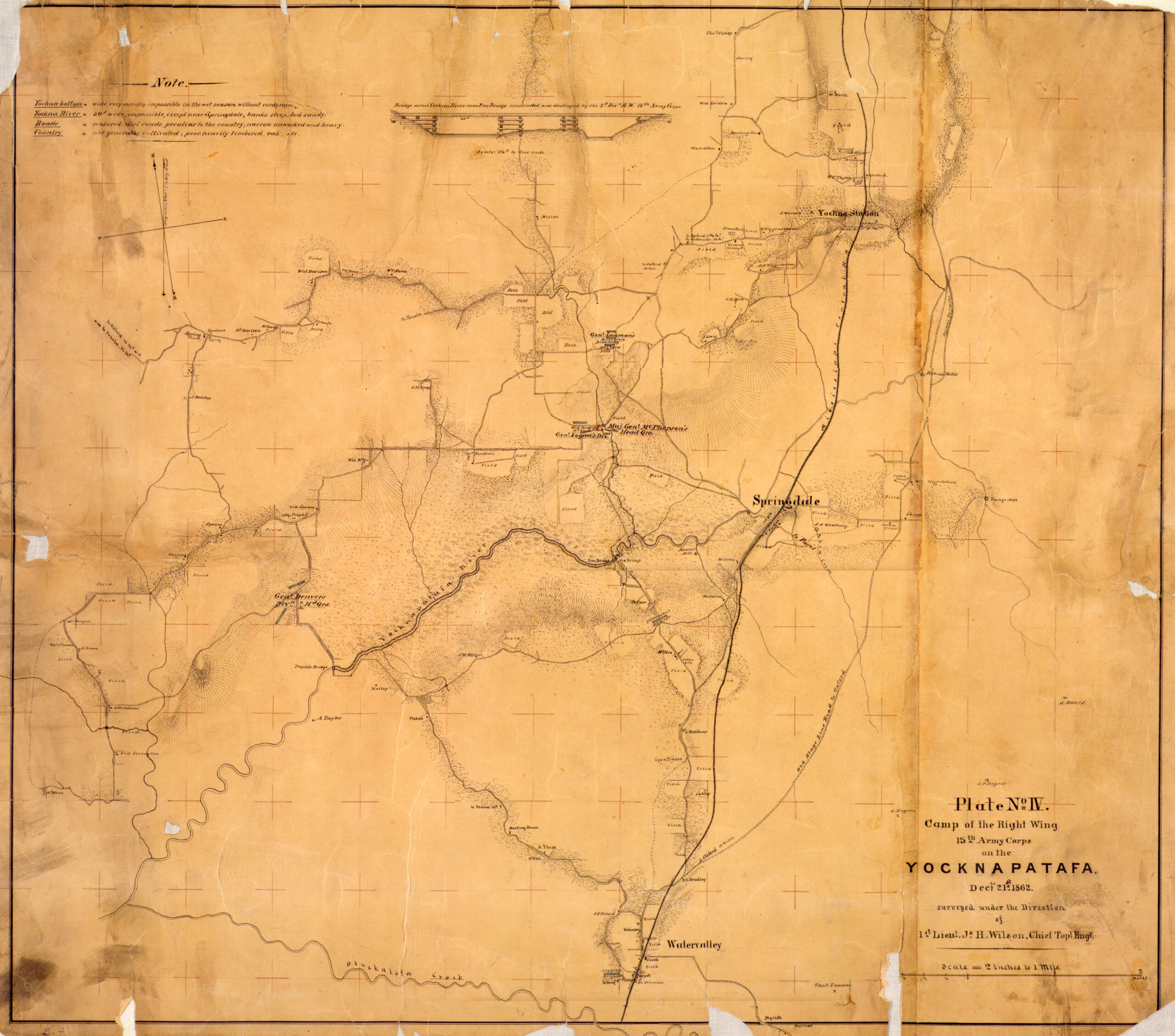

The Northern troops came down from Holly Springs to Waterford to Abbeville, and there was a large skirmish at the Tallahatchie River, on down to Springdale. Always, the railroad was the focal point of these skirmishes. In 1862, the Tallahatchie Bridge was taken at Springdale. After the Federal soldiers took Water Valley, they moved onward to Coffeeville for the Battle of Coffeeville in December of 1862.

“By November 1862, Northern Mississippi was securely in the hands of the Union army after key, yet costly, wins at Shiloh, Iuka, and Corinth. General Ulysses S. Grant began the Mississippi Central Railroad Campaign, an overland push (following the main rail line through the heart of Mississippi, capturing the towns and rail along the way) into Mississippi with the goal of capturing Vicksburg in conjunction with General William Tecumseh Sherman, who would follow the river southward.

“Outside of Coffeeville, the Confederate command decided to ambush the harassing enemy cavalry. On December 5, under the command of Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, the men of Baldwin, Tilghman and Rust’s brigades with artillery and support from W. H. Jackson’s units, hid on a wooded ridge alongside the Water Valley–Coffeeville Road.

“Around 2:30 pm, the Union Cavalry (led by Colonel Theophilus Lyle Dickey) approached Coffeeville within one mile. When the Cavalry was within 50 yards of the Confederate positions, it was fired upon by artillery, followed by volleys of infantry fire. After a skirmish, the Confederates pushed the Union Cavalry back about three miles to the head of Grant’s column. The pursuit halted and the Confederates returned to the ambush site. The Union Cavalry retreated to Water Valley. The fighting lasted from around 4 pm until dark.[1] The Battle of Coffeeville brought Grant’s Mississippi invasion via Tennessee to a halt. He pulled his army back to Oxford.” Wikipedia

The railroad down to Water Valley was in the hands of the Federal Troops.

Part 4: The Jackson District was in the hands of the Federal army.

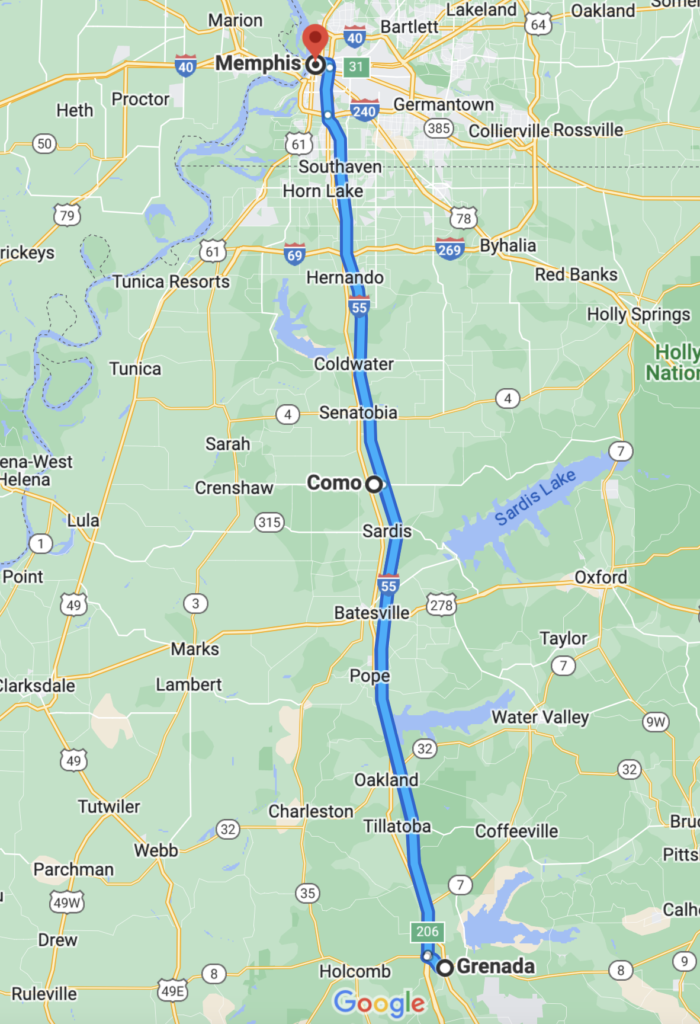

The M&T Railroad [Mississippi & Tennessee] was chartered from Grenada to Memphis Because of the Cotton grown there, Como, MS, was important in that effort.

During the Civil War, the two office trains from the Mississippi Central and the M&T were hidden. The M& T was hidden in the forest around Hardy, and the Mississippi Central Office train car was hidden down at Duck Hill. The lines were taken up to help protect these office train cars. They maintained a telegraph wire out of these hidden cars to the tracks that were not hidden.

Read Illinois Central: Main Line of Mid-America by Donald J. Hamburger

Part 5: There was a Train Wreck at Duck Hill, and 34 Confederate Soldiers were killed in that wreck.

Supposedly, the mourning for those soldiers caused the railroaders to sink into a bout of drinking. After white lightning had restored the courage of one of the engineers, he drove up to Abbeville and rescued Confederate soldiers.

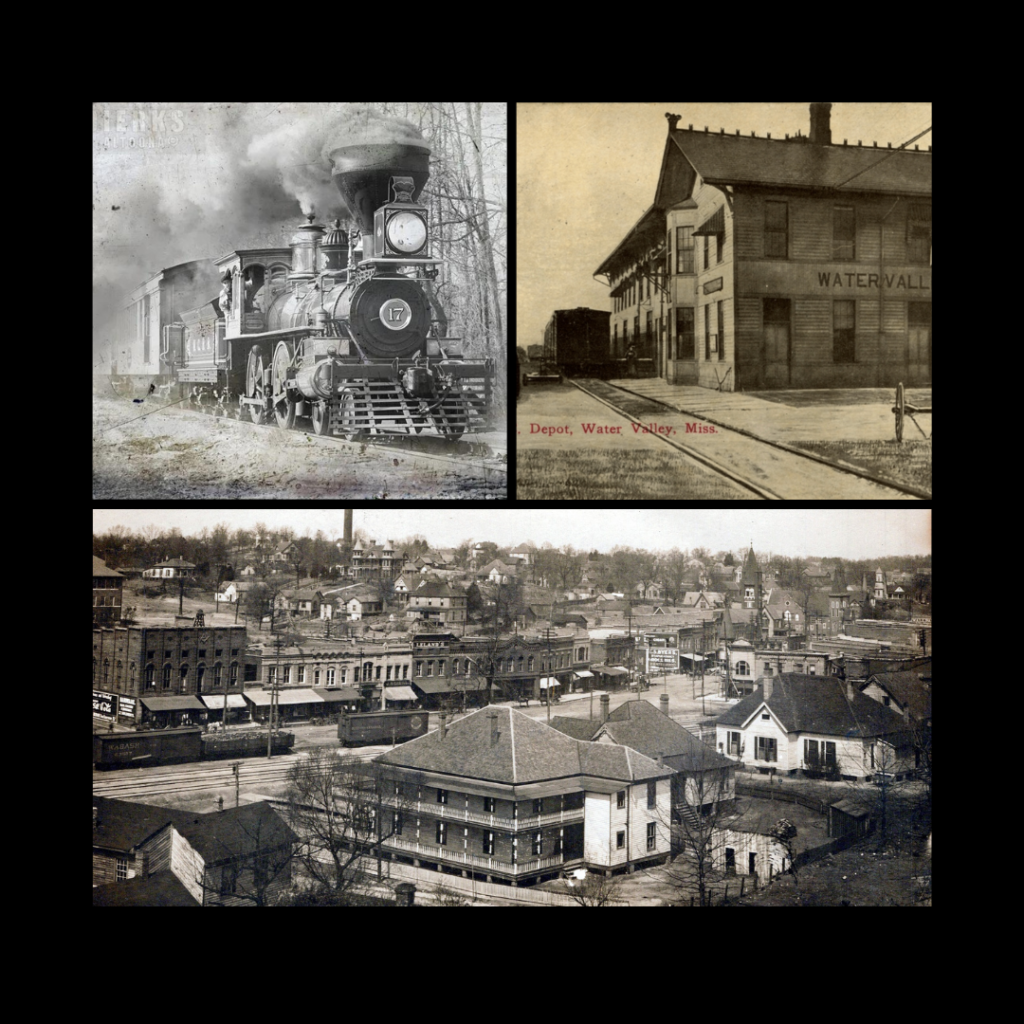

Until 1866, the train shops were in Holly Springs. In 1866, the shops were moved to Water Valley.

The headquarters of one of the districts was in Water Valley.

Part 6: Reconstruction of Railroad in Water Valley

Barron Caulfield’s great grandfather Colonel Frost, who had been captured in Canton and had been a prisoner, was brought to Water Valley.

“One of the most interesting characters on the Caulfield-Leland side of the family was Captain E.D. Frost. (March 17, 1825) See Edward Dickerson Frost). Frost, a civil engineer came to Water Valley from Battlesboro, Vt., by way of Decatur, Ga., and Jackson, MS. …

“Tradition has it that during the ‘War of Northern Aggression,’ Frost’s brother was taken prisoner. Captain Frost arranged his release. Capt. Frost was himself taken prisoner at Canton, MS. Although he remained in prison in Ohio until the end of the war, his brother helped arrange his quick release when hostilities ceased.

“Captain Frost surveyed the right of way for the Mississippi Central Railroad through Water Valley and lived here for about eight years. …” Barron Caulfield, The History of Yalobusha County

Some guys in Abbeville got together a mule train.

“mule train (plural mule trains) A connected or unconnected line of mules, pulling or carrying cargo or riders.” Wiktionary

One of the men was a man named Kirby. Probably related to Jack Kirby.

Tallahatchie Road to Holly Springs.

Daniel Wagner – Merchants came to Water Valley. It was obvious that WV would be a big railroad town, but a depression destroyed the momentum. McComb from New Jersey came down and built a successful town that became McComb. He gained control of the railroad, but he left it in debt.

The Illinois Central Railroad began to rebuild the railroad industry. The passenger trains were carried to Cairo, IL on barges. [Cairo to Kentucky]

The bridge was built

July 1881, the gauge of rails was changed from 5’ to 4.81/2.’The wheels were narrowed, too,

Part 7

After the WV Depot became the Division Office—a 2-story depot. Prior to that the Depot was at a hotel. The hotel was not built to be a hotel. It was built to be a railroad division office. The depot was enlarged several times until 1945, when all the offices were moved to Jackson, TN.

In 1889, a bridge was built across the Ohio River.

Water Valley had 38 or 39 trains pass each day.

In 1896,

The era of the Steam Engines was from the late 1890s. They had as many 5 or 6 banana trains each day. Banana Expresses.

There was a huge steam train force in Water Valley.