Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from an intaglio in the British Museum.

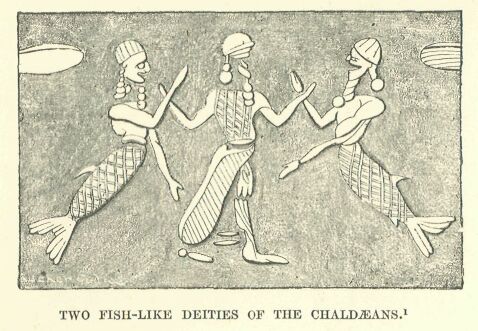

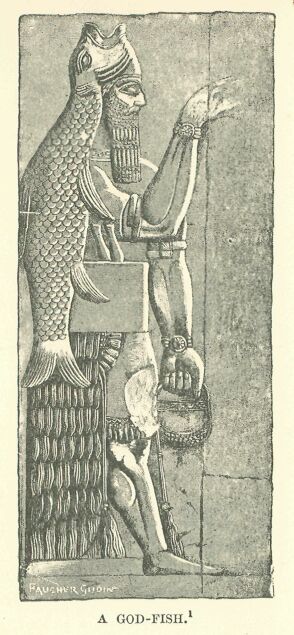

“After the death of Alôros, his son Alaparos ruled for three sari, after which Amillaros, of the city of Pantibibla, reigned thirteen sari. It was under him that there issued from the Bed Sea a second Annedôtos, resembling Oannes in his semi-divine shape, half man and half fish. After him Ammenon, also from Pantibibla, a Chaldaean, ruled for a term of twelve sari; under him, they say, the mysterious Oannes appeared.

“Afterwards Amelagaros of Pantibibla governed for eighteen sari; then Davos, the shepherd from Pantibibla, reigned ten sari: under him there issued from the Red Sea a fourth Annedôtos, who had a form similar to the others, being made up of man and fish. After him Bvedoranchos of Pantibibla reigned for eighteen sari; in his time there issued yet another monster, named Anôdaphos, from the sea. These various monsters developed carefully and in detail that which Oannes had set forth in a brief way. Then Amempsinos of Larancha, a Chalæan, reigned ten sari; and Obartes, also a Chaldæan, of Larancha, eight sari. Finally, on the death of Obartes, his son Xisuthros held the sceptre for eighteen sari. It was under him that the great deluge took place. Thus ten kings are to be reckoned in all, and the duration of their combined reigns amounts to one hundred and twenty sari. From the beginning of the world to the Deluge they reckoned 691,200 years, of which 259,200 had passed before the coming of Alôros, and the remaining 432,000 were generously distributed between this prince and his immediate successors: the Greek and Latin writers had certainly a fine occasion for amusement over these fabulous numbers of years which the Chaldæans assigned to the lives and reigns of their first kings.

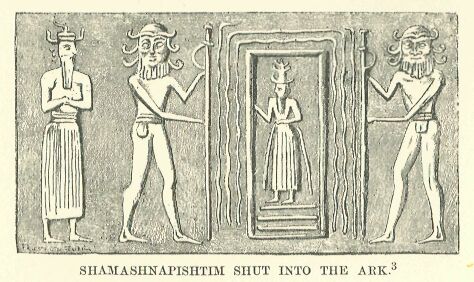

“Men in the mean time became wicked; they lost the habit of offering sacrifices to the gods, and the gods, justly indignant at this negligence, resolved to be avenged.* Now, Shamashnapishtim I was reigning at this time in Shurippak, the “town of the ship:” he and all his family were saved, and he related afterwards to one of his descendants how Ea had snatched him from the disaster which fell upon his people.** “Shurippak, the city which thou thyself knowest, is situated on the bank of the Euphrates; it was already an ancient town when the hearts of the gods who resided in it impelled them to bring the deluge upon it—the great gods as many as they are; their father Anu, their counsellor Bel the warrior, their throne-bearer Ninib, their prince Innugi. The master of wisdom, Ea, took his seat with them,*** and, moved with pity, was anxious to warn Shamashnapishtim, his servant, of the peril which threatened him;” but it was a very serious affair to betray to a mortal a secret of heaven, and as he did not venture to do so in a direct manner, his inventive mind suggested to him an artifice.

Build a Wooden House

“He confided to a hedge of reeds the resolution that had been adopted:* “Hedge, hedge, wall, wall! Hearken, hedge, and understand well, wall! Man of Shurippak, son of Ubaratutu, construct a wooden house, build a ship, abandon thy goods, seek life; throw away thy possessions, save thy life, and place in the vessel all the seed of life. The ship which thou shalt build, let its proportions be exactly measured, let its dimensions and shape be well arranged, then launch it in the sea.” Shamashnapishtim heard the address to the field of reeds, or perhaps the reeds repeated it to him. “I understood it, and I said to my master Ea ‘The command, O my master, which thou hast thus enunciated, I myself will respect it, and I will execute it: but what shall I say to the town, the people and the elders?’” Ea opened his mouth and spake; he said to his servant: “Answer thus and say to them: ‘Because Bel hates me, I will no longer dwell in your town, and upon the land of Bel I will no longer lay my head, but I will go upon the sea, and will dwell with Ea my master. Now Bel will make rain to fall upon you, upon the swarm of birds and the multitude of fishes, upon all the animals of the field, and upon all the crops; but Ea will give you a sign: the god who rules the rain will cause to fall upon you, on a certain evening, an abundant rain. When the dawn of the next day appears, the deluge will begin, which will cover the earth and drown all living things.’” Shamashnapishtim repeated the warning to the people, but the people refused to believe it, and turned him into ridicule. The work went rapidly forward: the hull was a hundred and forty cubits long, the deck one hundred and forty broad; all the joints were caulked with pitch and bitumen. A solemn festival was observed at its completion, and the embarkation began.** “All that I possessed I filled the ship with it all that I had of silver, I filled it with it; all that I had of gold I filled it with it, all that I had of the seed of life of every kind I filled it with it; I caused all my family and my servants to go up into it; beasts of the field, wild beasts of the field, I caused them to go up all together. Shamash had given me a sign: ‘When the god who rules the rain, in the evening shall cause an abundant rain to fall, enter into the ship and close thy door.’ The sign was revealed: the god who rules the rain caused to fall one night an abundant rain. The day, I feared its dawning; I feared to see the daylight; I entered into the ship and I shut the door; that the ship might be guided, I handed over to Buzur-Bel, the pilot, the great ark and its fortunes.”

“As soon as the morning became clear, a black cloud arose from the foundations of heaven. Bamman growled in its bosom; Nebo and Marduk ran before it—ran like two throne-bearers over hill and dale. Nera the Great tore up the stake to which the ark was moored. Ninib came up quickly; he began the attack; the Anunnaki raised their torches and made the earth to tremble at their brilliancy; the tempest of Ramman scaled the heaven, changed all the light to darkness, flooded the earth like a lake.* For a whole day the hurricane raged, and blew violently over the mountains and over the country; the tempest rushed upon men like the shock of an army, brother no longer beheld brother, men recognized each other no more.

“In heaven, the gods were afraid of the deluge;* they betook themselves to flight, they clambered to the firmament of Anu; the gods, howling like dogs, cowered upon the parapet.** Ishtar wailed like a woman in travail; she cried out, “the lady of life, the goddess with the beautiful voice: ‘The past returns to clay, because I have prophesied evil before the gods! Prophesying evil before the gods, I have counselled the attack to bring my men to nothing; and these to whom I myself have given birth, where are they? Like the spawn of fish they encumber the sea! ‘The gods wept with her over the affair of the Anunnaki;’ the gods, in the place where they sat weeping, their lips were closed.” It was not pity only which made their tears to flow: there were mixed up with it feelings of regret and fears for the future. Mankind once destroyed, who would then make the accustomed offerings? The inconsiderate anger of Bel, while punishing the impiety of their creatures, had inflicted injury upon themselves. “Six days and nights the wind continued, the deluge and the tempest raged.

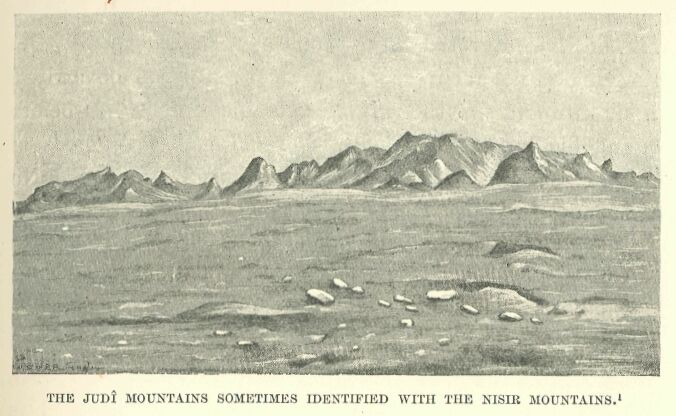

‘The seventh day at daybreak the storm abated; the deluge, which had carried on warfare like an army, ceased, the sea became calm and the hurricane disappeared, the deluge ceased. I surveyed the sea with my eyes, raising my voice; but all mankind had returned to clay, neither fields nor woods could be distinguished.*** I opened the hatchway and the light fell upon my face; I sank down, I cowered, I wept, and my tears ran down my cheeks when I beheld the world all terror and all sea. At the end of twelve days, a point of land stood up from the waters, the ship touched the land of Nisir:**** the mountain of Nisir stopped the ship and permitted it to float no longer. One day, two days, the mountain of Nisir stopped the ship and permitted it to float no longer.

“Three days, four days, the mountain of Nisir* stopped the ship and permitted it to float no longer. Five days, six days, the mountain of Nisir stopped the ship and permitted it to float no longer. The seventh day, at dawn, I took out a dove and let it go: the dove went, turned about, and as there was no place to alight upon, came back. I took out a swallow and let it go: the swallow went, turned about, and as there was no place to alight upon, came back. I took out a raven and let it go: the raven went, and saw that the water had abated, and came near the ship flapping its wings, croaking, and returned no more.” Shamashnapishtim escaped from the deluge, but he did not know whether the divine wrath was appeased, or what would be done with him when it became known that he still lived.** He resolved to conciliate the gods by expiatory ceremonies. “I sent forth the inhabitants of the ark towards the four winds, I made an offering, I poured out a propitiatory libation on the summit of the mountain. I set up seven and seven vessels, and I placed there some sweet-smelling rushes, some cedar-wood, and storax.” He thereupon re-entered the ship to await there the effect of his sacrifice

.

“The gods, who no longer hoped for such a wind-fall, accepted the sacrifice with a wondering joy. “The gods sniffed up the odour, the gods sniffed up the excellent odour, the gods gathered like flies above the offering. “When Ishtar, the mistress of life, came in her turn, she held up the great amulet which Anu had made for her.” * She was still furious against those who had determined upon the destruction of mankind, especially against Bel: “These gods, I swear it on the necklace of my neck! I will not forget them; these days I will remember, and will not forget them for ever. Let the other gods come quickly to take part in the offering. Bel shall have no part in the offering, for he was not wise: but he has caused the deluge, and he has devoted my people to destruction.” Bel himself had not recovered his temper: “When he arrived in his turn and saw the ship, he remained immovable before it, and his heart was filled with rage against the gods of heaven. ‘Who is he who has come out of it living? No man must survive the destruction!’” The gods had everything to fear from his anger: Ninib was eager to exculpate himself, and to put the blame upon the right person. Ea did not disavow his acts: “he opened his mouth and spake; he said to Bel the warrior: ‘Thou, the wisest among the gods, O warrior, why wert thou not wise, and didst cause the deluge? The sinner, make him responsible for his sin; the criminal, make him responsible for his crime: but be calm, and do not cut off all; be patient, and do not drown all. What was the good of causing the deluge? A lion had only to come to decimate the people. What was the good of causing the deluge? A leopard had only to come to decimate the people. What was the good of causing the deluge? Famine had only to present itself to desolate the country. What was the good of causing the deluge? Nera the Plague had only to come to destroy the people. As for me, I did, not reveal the judgment of the gods: I caused Khasisadra to dream a dream, and he became aware of the judgment of the gods, and then he made his resolve.’” Bel was pacified at the words of Ea: “he went up into the interior of the ship; he took hold of my hand and made me go up, even me; he made my wife go up, and he pushed her to my side; he turned our faces towards him, he placed himself between us, and blessed us: ‘Up to this time Shamashnapishtim was a man: henceforward let Shamashnapishtim and his wife be reverenced like us, the gods, and let Shamashnapishtim dwell afar off, at the mouth of the seas, and he carried us away and placed us afar off, at the mouth of the seas.’” Another form of the legend relates that by an order of the god, Xisuthros, before embarking, had buried in the town of Sippara all the books in which his ancestors had set forth the sacred sciences—books of oracles and omens, “in which were recorded the beginning, the middle, and the end. When he had disappeared, those of his companions who remained on board, seeing that he did not return, went out and set off in search of him, calling him by name. He did not show himself to them, but a voice from heaven enjoined upon them to be devout towards the gods, to return to Babylon and dig up the books in order that they might be handed down to future generations; the voice also informed them that the country in which they were was Armenia. They offered sacrifice in turn, they regained their country on foot, they dug up the books of Sippara and wrote many more; afterwards they refounded Babylon.” It was even maintained in the time of the Seleucido, that a portion of the ark existed on one of the summits of the Gordyæan mountains.** Pilgrimages were made to it, and the faithful scraped off the bitumen which covered it, to make out of it amulets of sovereign virtue against evil spells.”‘ G. Maspero. History of Egypt; Chaldea, Babylonia, and Assyria. vol.3.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.