“He who judges the first century by the nineteenth will fall into countless errors. He who thinks that the Christianity of the fourth century was identical with that of the New-Testament period, will go widely astray. He who does not look carefully into the history of religions before the time of Christ, and into the pagan influences which surrounded infant Christianity, cannot understand its subsequent history. He who cannot rise above denominational limitations and credal restrictions cannot become a successful student of early Church history, nor of present tendencies, nor of future developments.” Lewis, Abram Herbert. Paganism Surviving in Christianity, pg. vi.

PAGAN SUN-WORSHIP.

“Sun-Worship the Oldest and Most Widely Diffused Form of Paganism….

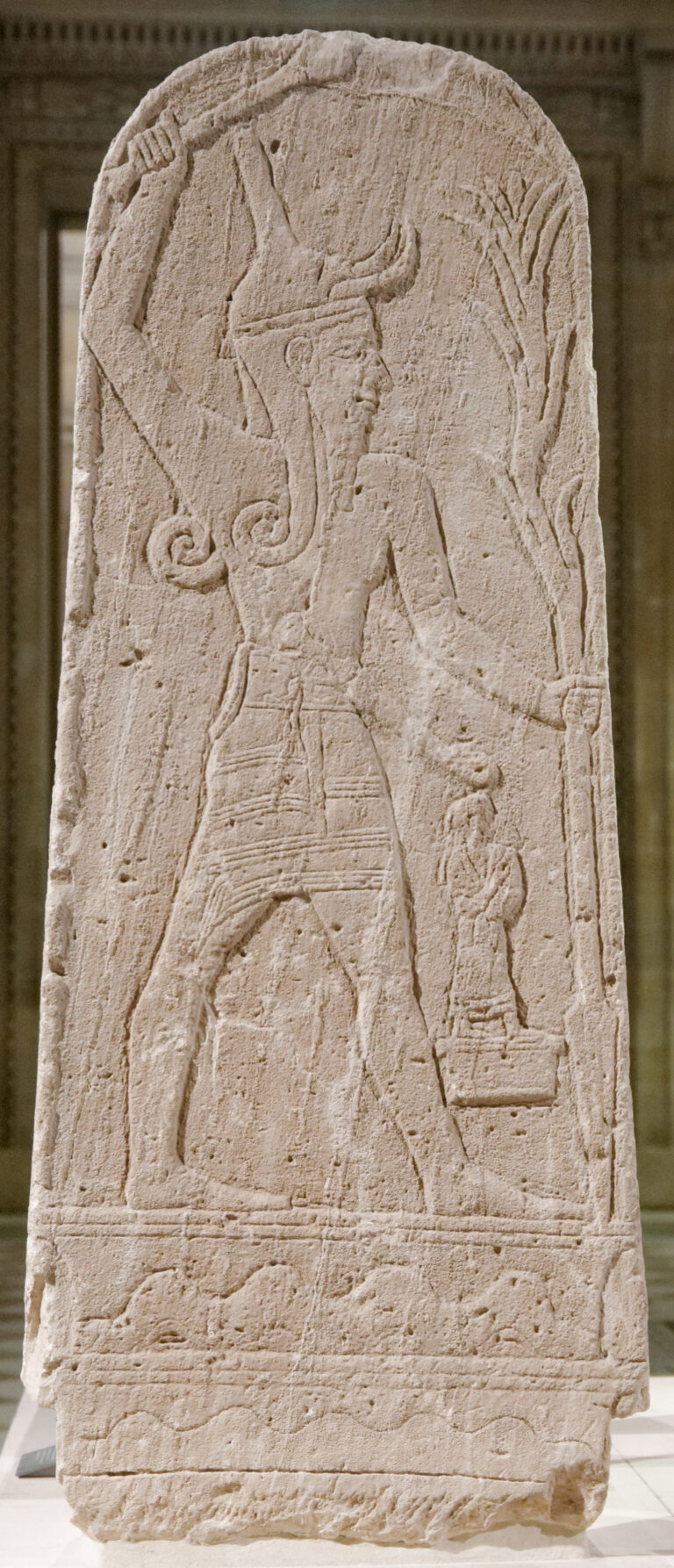

“The sun-god, under various names, Mithras, Baal, Apollo, etc., was the chief god of the heathen pantheon. A direct conflict between him and Jehovah appears wherever paganism and revealed religion came in contact.

“As “Baal,” “Lord” of the universe and of the productive forces in nature and in man, this sun-god was the pre-eminent divinity in ancient Palestine and throughout Phœnicia. The chosen people of God were assailed and corrupted by this cult, even while they were in the desert,[143] being led away by the women of Moab. During the period of the Judges, Baal-worship was the besetting sin of Israel, which the most vigorous measures could not eradicate.[144][157] A reformation came under Saul and David, only to be followed by a relapse under Solomon, which culminated in the exclusion of Jehovah-worship under Ahab.[145] Jehu broke the power of the cult, for a time, but the people soon returned to it.[146] It also spread like a virus through Judah; repressed by Hezekiah, but continued by Manasseh.[147]

Image Credit: Wiikipedia

“In its lowest forms it was so closely allied to sex-worship, Phallicism, that it lent great power to that debasing licentiousness, which sanctified lust, and made prostitution of virtue a religious duty.

“Sun-worship was both powerful and popular in the Roman Empire when Christianity came into contact with Western thought. It furnished abundant material for the corrupting process….

“…churches with the altar so that men should worship toward the east—[The sun appears to rise in the east.] …Baal’s and Apollo’s day, “Sunday,” in place of the Sabbath, which had always represented, and yet represents, Jehovah, maker of heaven and earth. The introduction of Sunday into Christianity was a continuation of the old-time conflict between Baal and Jehovah.

“The definite and systematic manner in which the corrupting process was carried forward is clearly seen by the preparatory steps which opened the way for paganism to thrust the sun’s day upon Christianity. … While men still had regard for the Sabbath, they could not entirely give up the law of Jehovah on which it was based, and thus the fundamental doctrines of paganism were still held in check.

Lights in Worship.

“The pagan origin of lights in worship is universally acknowledged. ….

Orientation.

‘Another residuum from sun-worship led to building churches with the altar at the east, praying toward the east, burying the dead with reference to the east, etc. Of the pagan origin of the custom, Gale speaks as follows:

“Another piece of Pagan Demonolatry was their ceremony of bowing and worshipping towards the East. For the Pagans universally worshipped the sun as their supreme[266] God,,,, [the Jews in Babylon usually worshipped west, because Jerusalem stood west thence). Hence also they built their temples and buried their dead towards the East. So Diogenes Laertius, in the life of Solon, says: that the Athenians buried their dead towards the East, the head of their graves being made that way. And do not Anti-Christ and his sons exactly follow this Pagan ceremony in building their temples and High Altars towards the East, and in bowing that way in their worship?”[238]

“Various explanations were made concerning this practice, to cover up the prominence of this paganism. For instance, Clement of Alexandria says:

“And since the dawn is an image of the day of birth, and from that point the light which has shone forth at first from the darkness, increases, there has also dawned on those involved in darkness a day of the knowledge of truth. In correspondence with the manner of the sun’s rising, prayers are made looking towards the sunrise in the East. Whence also the most ancient temples looked towards the West, that people might be taught to turn to the East when facing the images. ‘Let my prayer be directed before thee as incense, the uplifting of my hands as the evening sacrifice,’ say the Psalms.”[239]

Tertullian seeks to avoid the charge of paganism, while defending this practice, as follows:

“Others, with greater regard to good manners, it must be confessed, suppose that the sun is the god of the Christians, because it is a well known fact that we pray toward the East, or because we make Sunday a day of festivity. What then? Do you do less than this? Do not many among you, with an affectation of sometimes worshipping the heavenly bodies, likewise, move your lips in the direction of the sunrise? It is you, at all events, who have even admitted the sun into the calendar of the week; and you have selected its day, in preference to the preceding day, as the most suitable in the week, for either an entire abstinence from the bath, or for its postponement until the evening, or for taking rest, and for banqueting.”[240]

Easter Fires.

“Another element of pagan sun-worship continues to the present time in the Easter fires, which abound especially in Northern Europe. Fire is regarded as a living thing, in Teutonic mythology. It is often spoken of as a bird, the “Red Cock.” Notfuer, “Need-fire,” is yet produced by friction, at certain times. Such fire is deemed sacred. On such occasions all fires in the neighborhood are extinguished, that they may be rekindled from the Notfuer. This fire is yet used to ward off evil,[268] and to cure diseases in domestic animals. Traces of sex-worship appear in connection with the producing of this sacred fire; “two chaste boys” must pull the ropes which produce the friction necessary to generate the fire; and a “chaste youth” must strike the light for curing the disease known as “St. Anthony’s fire.” In Scotland such fire is held as a safeguard against the “bewitching of domestic animals.”

“Grimm, who is the highest authority on the mythology of Northern Europe, has abundant material touching all forms of fire-worship in that region. Here is a single extract with reference to Easter Fires.

“At all the cities, towns and villages of the country, towards evening on the first (or third) day of Easter, there is lighted every year, on mountain and hill, a great fire of straw turf and wood, amidst a concourse and jubilation, not only of the young, but of many grown up people. On the Weser, especially in Schaumburg, they tie up a tar barrel on a fir tree wrapt around with straw, and set it on fire at night. Men and maids, and all who come dance, exulting and singing, hats are waved, handkerchiefs thrown into the fire. The mountains all around are lighted up, and it is an elevating spectacle, scarcely paralleled by any thing else, to survey the country for many miles around from one of the higher points, and in every direction at once to see a vast number of these bonfires, brighter or fainter, blazing up to heaven. In some places they marched up the hill in stately procession,[269] carrying white rods: by turns they sang Easter hymns, grasping each other’s hands, and at the Hallelujah, clashed their rods together. They liked to carry some of the fire home with them.

“For these ignes paschales there is no authority reaching beyond the sixteenth century; but they must be a great deal older, if only for the contrast with Midsummer fires, which never could penetrate into North Germany, because the people there held fast by their Easter fires. Now seeing that the fires of St. John, as we shall presently show, are more immediately connected with the Christian Church than those of Easter, it is not unreasonable to trace these all the way back to the worship of the goddess Ostara, or Eastre, who seems to have been more a Saxon and Anglican divinity than one revered all over Germany. Her name and her fires, which are likely to have come at the beginning of May, would, after the conversion of the Saxons, be shifted back to the Christian feast. Those mountain fires of the people are scarcely derivable from the taper lighted in the Church the same day: it is true that Boniface calls it ignis paschalis, and such Easter lights are mentioned in the sixteenth century. Even now, in the Hildesheim country, they light the lamp on Maundy Thursday, and that on Easter day, at an Easter fire which has been struck with a steel. The people flock to this fire, carrying oaken crosses, or simply crossed sticks, which they set on fire and then preserve for a whole year. But the common folk distinguish between this fire and the wild fire produced by rubbing wood. Jager speaks of a consecration fire of logs.”[241]

Midsummer Fires.

“Midsummer was the central point of a great pagan festival in honor of the sun, who had then reached his greatest height, from which he must soon decline. Catholic Christianity continued these festivals, in St. John Baptist Day. Many of the peculiarities of these midsummer fires were similar to those of the Easter fires already noticed. The following description of the modern festival in Germany is taken from Grimm:

“We have a fuller description of a Midsummer fire, made in 1823 at Konz, a Lorrainian but still German village, on the Moselle, near Sierk and Thionville. Every house delivers a truss of straw on the top of the Stromberg, where men and youths assemble toward evening. Women and girls are stationed by the Burbach springs. Then a huge wheel is wrapt round with straw, so that none of the wood is left in sight, a strong pole is passed through the middle, which sticks out a yard on each side, and is grasped by the guiders of the wheel; the remainder of the straw is tied up into a number of small torches. At a signal given by the Maire of Sierk (who according to the ancient custom, earns a basket of cherries by the service), the wheel is lighted with a torch, and set rapidly in motion; a shout of joy is raised, all wave their torches on high, part of the men stay on the hill, part follow the rolling globe of fire, as it is guided down the hill to the Moselle. It often goes out first: but if alight when it touches the river, it prognosticates an abundant vintage, and the Konz people have a right to levy a tun of white wine from the[271] adjacent vineyards. Whilst the wheel is rushing past the women and the girls, they break out into cries of joy, answered by the men on the hill, and inhabitants of neighboring villages, who have flocked to the river side, mingle their voices in the universal rejoicing.”[242]

Beltane or Baal Fires.

The Beltane or Baal fires and the ancient sacrifices to the sun-god still continue in modified form in Scotland. Grimm speaks of them as follows:

“The present custom is thus described by Armstrong sub v. bealtainn: In some parts of the Highlands the young folks of a hamlet meet in the moors, on the first of May. They cut a table in the green sod, of a round figure, by cutting a trench in the ground, of such circumference as to hold the whole company. They then kindle a fire and dress a repast of eggs and milk, in the consistence of a custard. They knead a cake of oatmeal, which is toasted at the embers, against a stone. After the custard is eaten up, they divide the cake in so many portions, as similar as possible to one another in size and shape, as there are persons in the company. They daub one of these portions with charcoal, until it is perfectly black. They then put all the bits of the cake into a bonnet, and every one, blindfold, draws out a portion. The bonnet-holder is entitled to the last bit. Whoever draws the black bit is the devoted person who is to be sacrificed to Baal, whose favor they mean to implore in rendering the year productive. The devoted person is compelled to leap three times over the flames. Here the reference to the worship of a deity is[272] too plain to be mistaken; we see by the leaping over the flame, that the main point was, to select a human being to propitiate the god, and make him merciful; that afterwards an animal sacrifice was substituted for him, and finally nothing remained of the bodily immolation but a leap through the fire, for man and beast. The holy rite of friction is not mentioned here, but as it was necessary for the ‘needfire’ that purged pestilence, it must originally have been much more in requisition at the great yearly festival.”[243]

Lewis, Abram Herbert. Paganism Surviving in Christianity

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.