Plants Connected with Birds and Animals.

“The association of trees and birds has been the theme of the most ancient writers. The Skalds have sung how an Eagle sat in stately majesty on the topmost branch of Yggdrasill, whilst the keen-eyed Hawk hovered around. The Vedas record how the Pippala of the Hindu Paradise was daily visited by two beauteous birds, one of which fed from its celestial food, whilst its companion poured forth delicious melody from its reed-like throat. On the summit of the mystic Soma-tree were perched two birds, the one engaged in expressing the immortalising Soma-juice, the other feeding on the Figs which hung from the branches of the sacred tree. A bird, bearing in its beak a twig plucked from its favourite tree, admonished the patriarch Noah that the waters of the flood were subsiding from the deluged world.

In olden times there appears to have been a notion that in some cases plants could not be germinated excepting through the direct intervention of birds.

Thus Bacon tells us of a tradition, current in his day, that a bird, called a Missel-bird, fed upon a seed which, being unable to digest, she evacuated whole; and that this seed, falling upon boughs of trees, put forth the Mistletoe.

A similar story is told by Tavernier of the Nutmeg. “It is observable,” he says, “that the Nutmeg-tree is never planted: this has been attested to me by several persons who have resided many years in the islands of Bonda. I have been assured that when the nuts are ripe, there come certain birds from the islands that lie towards the South, who swallow them down whole, and evacuate them whole likewise, without ever having digested them. These nuts being then covered with a viscous and glutinous matter, when they fall on the ground, take root, vegetate, and produce a tree, which would not grow from them if they were planted like other trees.”

The Druids, dwelling as they did in groves and forests, frequented by birds and animals, were adepts at interpreting the meaning of their actions and sounds. A knowledge of the language of the bird and animal kingdoms was deemed by them a marvellous gift, which was only to be imparted to the priestess who should be fortunate enough to tread under foot the mystic Selago, or Golden Herb.

At a time when men had no almanack to warn them of the changing of the seasons, no calendar to guide them in the planting of their fields and gardens, the arrival and departure of birds helped to direct them in the cultivation of plants. So we find Ecclesiastes preached “a bird of the air shall carry the voice,” and in modern times the popular saying arose of “a little bird has told me.” Folkard

“Do not curse the king, even in your thought;

Do not curse the rich, even in your bedroom;

For a bird of the air may carry your voice,

And a bird in flight may tell the matter.” Ecclesiastes 10:20 NKJV

“This notion of the birds imparting knowledge is prettily rendered by Hans Christian Andersen, in his story of the Fir-tree, where the sapling wonders what is done with the trees taken out of the wood at Christmas time. “Ah, we know—we know,” twittered the Sparrows; “for we have looked in at the windows in yonder town.”

Dr. Solander tells us that the peasants of Upland remark that “When you see the Wheatear you may sow your grain,” for in this country there is seldom any severe frost after the Wheatear appears; and the shepherds of Salisbury Plain say:—

Aristophanes makes one of his characters say that in former times the Kite ruled the Greeks; his meaning being that in ancient days the Kite was looked upon as the sign of Spring and of the necessity of commencing active work in field and garden; and again, “The Crow points out the time for sowing when she flies croaking to Libya.” In another place he notices that the Cuckoo in like manner governed Phœnicia and Egypt, because when it cried Kokku, Kokku, it was considered time to reap the Wheat and Barley fields.

In our own country, this welcome harbinger of the Springtide has been associated with a number of vernal plants: we have the Cuckoo Flower (Lychnis Flos cuculi), Cuckoo’s Bread or Meat, and Cuckoo’s Sorrel (Oxalis Acetosella), Cuckoo Grass (Lazula campestris), and Shakspeare’s “Cuckoo Buds of yellow hue,” which are thought to be the buds of the Crowfoot (Ranunculus). The association in the popular rhyme of the Cuckoo with the Cherry-tree is explained by an old superstition that before it ceases its song, the Cuckoo must eat three good meals of Cherries. In Sussex, the Whitethorn is called the Cuckoo’s Bread-and-Cheese Tree, and an old proverb runs—

Mr. Parish has remarked that it is singular this name should be given to the Whitethorn, as among all Aryan nations the tree is associated with lightning, and the Cuckoo is connected with the lightning gods Jupiter and Thor.

Pliny relates that the Halcyon, or Kingfisher, at breeding-time, foretold calm and settled weather. The belief in the wisdom of birds obtained such an ascendancy over men’s minds, that we find at length no affair of moment was entered upon without consulting them.

Thus came in augury, by which was meant a forewarning of future events derived from prophetic birds. One of these systems of divinations, for the purpose of discovering some secret or future event was effected by means of a Cock and grains of Barley, in the following manner: the twenty-four letters of the alphabet having been written in the dust, upon each letter was laid a grain of Barley, and a Cock, over which previous incantations had been uttered, was let loose among them; those letters off which it pecked the Barley, being joined together, were then believed to declare the word of which they were in search.

The magician Jamblichus, desirous to find out who should succeed Valens in the imperial purple, made use of this divination, but the Cock only picked up four grains, viz., those which lay upon the (Greek) letters th. e. o. d., so that it was uncertain whether Theodosius, Theodotus, Theodorus, or Theodectes, was the person designed by the Fates. Valens, when informed of the matter, was so terribly enraged, that he put several persons to death simply because their names began with these letters. When, however, he proceeded to make search after the magicians themselves, Jamblichus put an end to his majesty’s life by a dose of poison, and he was succeeded by Theodosius in the empire of the East.

The loves of the Nightingale and the Rose have formed a favourite topic of Eastern poets. In a fragment by the celebrated Persian poet Attar, entitled Bulbul Nameh (the Book of the Nightingale), all the birds appear before Solomon, and charge the Nightingale with disturbing their rest by the broken and plaintive strains which he warbles forth in a sort of frenzy and intoxication. The Nightingale is summoned, questioned, and acquitted by the wise king, because the bird assures him that his vehement love for the Rose drives him to distraction, and causes him to break forth into those languishing and touching complaints which are laid to his charge. Thus the Persians believe that the Nightingale in Spring flutters around the Rose-bushes, uttering incessant complaints, till, overpowered by the strong scent, he drops stupefied to the ground. The impassioned bird makes his appearance in Eastern climes at the season when the Rose begins to blow: hence the legend that the beauteous flower bursts forth from its bud at the song of its ravished adorer. The Persian poet Jami says, “The Nightingales warbled their enchanting notes and rent the thin veils of the Rose-bud and the Rose;” and Moore has sung—

And in another place, the author of ‘Lalla Rookh’ asks—

Lord Byron has alluded to this pretty conceit in the ‘Giaour,’ when he sings—

Legend of the Red Rose

And in Thomson’s ‘Hymn to May,’ we find this allusion:—

In a sonnet by Sir Philip Sydney, afterwards set to music by Bateson, we read—

Shakspeare notices the story in the following quaint lines—

In Yorkshire, there is a tradition of Hops having been planted many years ago, near Doncaster, and of the Nightingale making its first appearance there about the same time. The popular idea was, that between the bird and the plant some mysterious connecting link existed. Be this as it may, both the Hops and the Nightingale disappeared long ago.

Legend of the Robin

It is not alone the Nightingale that has a legendary connection with a Thorn. Another favourite denizen of our groves may also lay claim to this distinction, inasmuch as, according to a tradition current in Brittany, its red breast was originally produced by the laceration of an historic Thorn. In this story it is said that, whilst our Saviour was bearing His cross on the way to Calvary, a little bird, struck with compassion at His sufferings, flew suddenly to Him, and plucked from His bleeding brow one of the cruel thorns of His mocking crown, steeped in His blood. In bearing it away in its beak, drops of the Divine blood fell upon the little bird’s breast, and dyed its plumage red; so that ever since the Red-breast has been treated as the friend of man, and is studiously protected by him from harm.

Whether or no this legend of the origin of our little friend’s red breast formerly influenced mankind in its favour, it is certain that the Robin has always been regarded with tenderness. Popular tradition, even earlier than the date of the story of the Children in the Wood, has made him our sexton with the aid of plants:—

It is noted in Gray’s Shakspeare that, according to the oldest traditions, if the Robin finds the dead body of a human being, he will cover the face at least with Moss and leaves.

The Wren is also credited with employing plants for acts of similar charity. In Reed’s old plays, we read—

A writer in one of our popular periodicals[15] gives another quaint quotation expressive of the tradition, from Stafford’s ‘Niobe dissolved into a Nilus’: “On her (the Nightingale) smiles Robin in his redde livvrie; who sits as a coroner on the murthred man; and seeing his body naked, plays the sorrie tailour to make him a Mossy rayment.” Folkard

Image Credit: Inga Moore, Illustrator of The Secret Garden

The Robin is Important in Burnett’s Novel The Secret Garden

“She could see the tops of trees above the wall, and when she stood still she saw a bird with a bright red breast sitting on the topmost branch of one of them, and suddenly he burst into his winter song—almost as if he had caught sight of her and was calling to her.

She stopped and listened to him and somehow his cheerful, friendly little whistle gave her a pleased feeling…” Burnett.

Mistletoe

“The oak mistletoe or “missel” was held in high veneration by the ancient Druids, who, regarding its parasitic character as a miracle and its evergreen nature as a symbol of immortality, worshipped it in their temples and used it as a panacea for the physical ailments of their followers. When the moon was six days old, the bunches were ceremoniously cut with a golden sickle, by the chief priest of the order and received with care into the spotless robes of one of the company, for if they fell to the unholy ground, their virtues were considered lost.

“Then, crowned with oak leaves and singing songs of thanksgiving, they bore the branches in solemn procession to the altars, where two white oxen were sacrificed to the gods.

“The custom of “kissing under the mistletoe” dates back to the days of Scandinavian mythology, when the god of darkness shot his rival, the immortal Apollo of the North, with an arrow made from its boughs. But the supposed victim being miraculously restored to life, the mistletoe was given into the keeping of the goddess of affection, as a symbol of love and not of death, to those who passed beneath it. A berry was required[8] to be picked with every kiss and presented to the maiden as a sign of good fortune, the privilege ceasing when all the berries were gathered.” Bertha F. Herrick. Myths and Legends of Christmastide.

Ancient Pagan Holidays Celebrated Today–Some of Them Are Celebrated as Christian

“The Missel or Missel-Thrush is sometimes called the Mistletoe-Thrush, because it feeds upon Mistletoe berries. Lord Bacon, in Sylva Sylvarum, refers (as already noted) to an old belief that the seeds of Mistletoe will not vegetate unless they have passed through the stomach of this bird.

“The Peony is said to cure epilepsy, if certain ceremonies are duly observed. A patient, however, must on no account taste the root, if a Woodpecker should happen to be in sight, or he will be certain to be stricken with blindness.

Spring-wort and Birds

[The word “wort” was added to plants known many years ago. Today, the word “root” is often exchanged for the word “word”. Bloodworth is a harbinger of spring.

“Among the many magical properties ascribed to the Spreng-wurzel (Spring-wort), or, as it is sometime called, the Blasting-root, is its power to reveal treasures. But this it can only do through the instrumentality of a bird, which is usually a green or black Woodpecker (according to Pliny, also the Raven; in Switzerland, the Hoopoe; in the Tyrol, the Swallow). In order to become possessed of a root of this magical plant, arrangements must be made with much care and circumspection, and the bird closely watched. When the old bird has temporarily left its nest, access to it must be stopped up by plugging the hole with wood. The bird, finding this, will fly away in search of the Spring-wort, and returning, will open the nest by touching the obstruction with the mystic root. Meanwhile a fire or a red cloth must be spread out closely, which will so startle the bird, that it will let the root fall from its bills, and it can thus be secured. Pliny relates of the Woodpecker, that the hen bird brings up her young in holes, and if the entrance be plugged up, no matter how securely, the old bird is able to force out the plug with an explosion caused by the plant. Aubrey confounds the Moonwort with the Springwort. He says:—“Sir Benet Hoskins, Baronet, told me that his keeper at his parke at Morehampton, in Herefordshire, did, for experiment’s sake, drive an iron naile thwert the hole of the Woodpecker’s nest, there being a tradition that the damme will bring some leafe to open it. He layed at the bottome of the tree a cleane sheet, and before many hours passed, the naile came out, and he found a leafe lying by it on the sheete. They say the Moonewort will doe such things.”

“Tradition tells us of a certain magical herb called Chora, which was also known as the Herba Meropis, or plant of the Merops, a bird which the Germans were familiar with under the name of Bömhechel or Baumhacker (Woodpecker). This bird builds its nest in high trees, but should anyone cover the young brood with something which prevents the parent bird from visiting the nest, it flies off in search of a herb. This is brought in the Merops’ beak, and held over the obstacle till it falls off or gives way.

In Swabia, the Springwort is regarded as a plant embodying electricity or lightning; but the Hoopoe takes the place of the Woodpecker in employing the herb for blasting and removing offensive obstacles. The Swabians, however, instead of a red cloth, place a pail of water, or kindle a fire, as the Hoopoe, wishing to destroy the Springwort, after using it, drops it either into fire or water. It is related of the Hoopoe, that one of these birds had a nest in an old wall in which there was a crevice. The proprietor, noticing the cleft in the wall, had it stopped up with plaster during the Hoopoe’s absence, so that when the poor bird returned to feed her young, she found that it was impossible to get to her nest. Thereupon she flew off in quest of a plant called Poa, thought to be Sainfoin or Lucerne, and, having found a spray, returned and applied it to the plaster, which instantly fell from the crevice, and allowed the Hoopoe ingress to her nest. Twice again did the owner plaster up the rent in his wall, and twice again did the persistent and sagacious bird apply the magic Poa with successful results.

“In Piedmont there grows a little plant which, as stated in a previous chapter, bears the name of the Herb of the Blessed Mary. This plant is known to the birds as being fatal when eaten: hence, when their young are stolen from them and imprisoned in cages, the parent birds, in order that death may release them from their life of bondage, gather a spray of this herb and carry it in their beaks to their imprisoned children.

“The connection between the Dove and the Olive has been set forth for all time in the Bible narrative of Noah and the Flood;

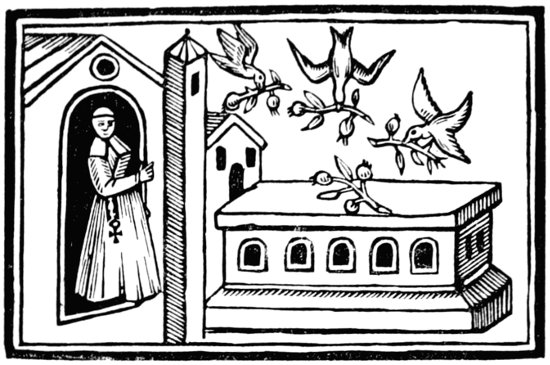

but it would seem from Sir John Maundevile’s account of the Church of St. Katherine, which existed at his time in the vicinity of Mount Sinai, that Ravens, Choughs, and Crows have emulated the example of the Dove, and carried Olive-branches to God-fearing people.

This Church of St. Katherine, we are told, marks the spot where God revealed Himself to Moses in the burning bush, and in it there were many lamps kept burning: the reason of this Maundevile thus explains:—“For thei han of Oyle of Olyves ynow bothe for to brenne in here lampes, and to ete also: And that plentee have thei be the Myracle of God. For the Ravenes and Crowes and the Choughes, and other Foules of the Contree assemblen hem there every Yeer ones, and fleen thider as in pilgrymage: and everyche of hem bringethe a Braunche of the Bayes or of Olive, in here bekes, in stede of Offryng, and leven hem there; of the whiche the monkes maken gret plentee of Oyle; and this is a gret Marvaylle.”

Pious Birds and Olives. From Maundevile’s Travels.

“The Church of the Transfiguration of Christ the Savior, or the Church of St. Catherine, is a church within the St. Catherine’s Monastery complex in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula:” Google ai

|

Church of St. Catherine

|

|

|---|---|

|

Location

|

Within the St. Catherine’s Monastery complex, on the slopes of Mount Sinai

|

|

Significance

|

Located where Moses encountered God in the Burning Bush, and where the prophet received the Ten Commandments

|

|

Features

|

Contains the Church of the Burning Bush, and is decorated with 6th century mosaics

|

“The ancients entertained a strong belief that birds were gifted with the knowledge of herbs, and that just as the Woodpecker and Hoopoe sought out the Springwort, wherewith to remove obstructions, so other birds made use of certain herbs which they knew possessed valuable medicinal or curative properties; thus Aristotle, Pliny, Dioscorides, and the old herbalists and botanical writers, all concur in stating that Swallows were in the habit of plucking Celandine (Chelidonium), and applying it to the eyes of their young, because, as Gerarde tells us, “With this herbe the dams restore sight to their young ones when their eies be put out.” W. Coles, fully accepting the fact as beyond cavil, thus moralizes upon it:—“It is known to such as have skill of nature what wonderful care she takes of the smallest creatures, giving to them a knowledge of medicine to help themselves, if haply diseases annoy them. The Swallow cureth her dim eyes with Celandine; the Wesell knoweth well the virtue of Herb Grace; the Dove the Verven; the Dogge dischargeth his mawe with a kind of Grasse; … and too long it were to reckon up all the medicines which the beestes are known to use by Nature’s direction only.” The same writer, in his ‘Adam and Eden,’ tells us that the Euphrasia, or Eyebright, derived its English name from the fact of its being used by Linnets and other birds to clear their sight. Says he: “Divers authors write that Goldfinches, Linnets, and some other birds make use of this herb for the repairing of their young ones’ sight. The purple and yellow spots and stripes which are upon the flowers of Eyebright very much resemble the diseases of the eyes, or bloodshot.”

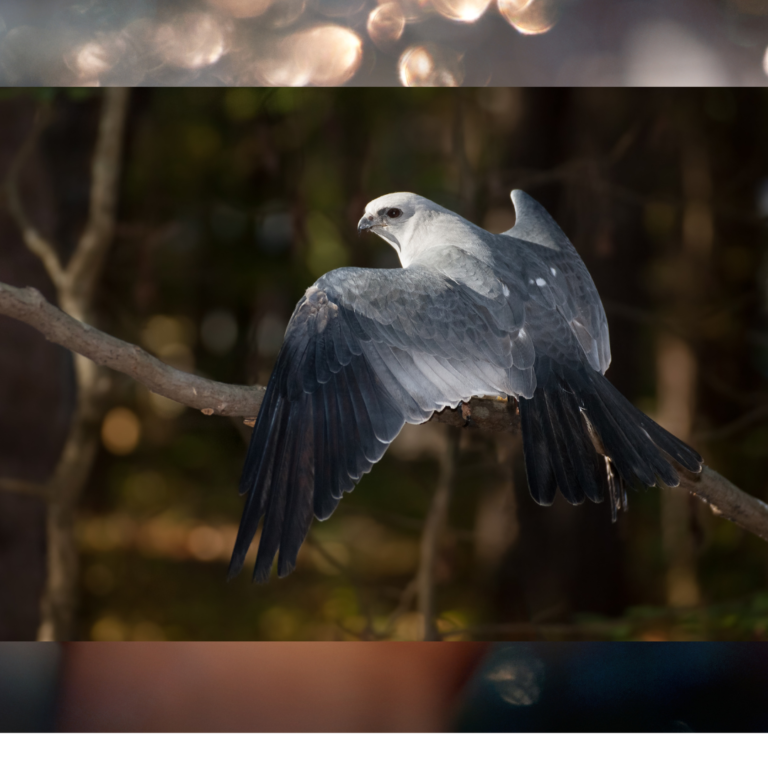

“Apuleius tells us that the Eagle, when he wishes to soar high and scan far and wide, plucks a wild Lettuce, and expressing the juice, rubs with it his eyes, which in consequence become wonderfully clear and far-seeing.

“The Hawk, for a similar purpose, was thought to employ the Hawk-bit, or Hawk-weed (Hieracium).” Folkard

Vervain

“Vervain has long been credited with magical properties and was used in ceremonies by the Druids of ancient Britain and Gaul. It is a traditional herbal medicine in both China and Europe. Dioscorides in the 1st century ce called vervain the ‘sacred herb,’ and for many centuries it was taken as a cure-all. It has tonic, restorative properties, and is used to relieve stress and anxiety and to improve digestive function. Chevallier, Andrew. Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine

Common Herbs & Herbal Medicines – An Alphabetical Directory by Common Name

“Pigeons and Doves, not to be behind their traditional enemy, discovered that Vervain possessed the power of curing dimness of vision, and were not slow to use it with that object: hence the plant obtained the name of Pigeon’s-grass. Geese were thought to “help their diseases” with Galium aparine, called on that account Goose-grass; and they are said to sometimes feed on the Potentilla anserina, or Goose Tansy. On the other hand, they were so averse to the herb known to the ancients as Chenomychon, that they took to flight the moment they spied it.

Legend of Goat’s Rue

“There is an old tradition of a certain life-giving herb, which was known to birds, and a story is told of how one day an old man watched two birds fighting till one was overcome. In an almost exhausted state it went and ate of a certain herb, and then returned to the onslaught. When the old man had observed this occur several times, he went and plucked the herb which had proved so valuable to the little bird; and when at last it came once more in search of the life-giving plant, and found it gone, it uttered a shrill cry, and fell down dead. The name of the herb is not given; but the story has such a strong family likeness to that narrated by Forestus, in which the Goat’s Rue is introduced, that, probably, Galega is the life-giving herb referred to. The story told by Forestus is as follows:—A certain old man once taking a walk by the bank of a river, saw a Lizard fighting with a Viper; so he quietly lay down on the ground, that he might the better witness the fight without being seen by the combatants. The Lizard, being the inferior in point of strength, was speedily wounded by a very powerful stroke from the Viper—so much so, that it lay on the turf as if dying. But shortly recovering itself, it crept through the rather long Grass, without being noticed by the Viper, along the bank of the river, to a certain herb (Goat’s Rue), growing there nigh at hand. The Lizard, having devoured it, regained at once its former strength, and returning to the Viper, attacked it in the same way as before, but was wounded again from receiving another deadly blow from the Viper. Once more the Lizard secretly made for the herb, to regain its strength, and being revived, it again engaged with its dangerous enemy—but in vain; for it experienced the same fate as before. Looking on, the old man wondered at the plant not less than at the battle; and in order to try if the herb possessed other hidden powers, he pulled it up secretly, while the Lizard was engaged afresh with the Viper. The Lizard having been again wounded, returned towards the herb, but not being able to find it in its accustomed place, it sank exhausted and died.

Plants Named for Birds

“Numerous plants have had the names of birds given to them, either from certain peculiarities in their structure resembling birds, or because they form acceptable food for the feathered race. Thus the Cock’s Comb is so called from the shape of its calyx; the Cock’s Foot, from the form of its spike; and the Cock’s Head (the Sainfoin), from the shape of the legume. The Crane’s Bill and the Heron’s Bill both derive their names from the form of their respective seed vessels. The Guinea Hen (Fritillaria meleagris) has been so called from its petals being spotted like this bird. The Pheasant’s Eye (Adonis autumnalis) owes its name to its bright red corolla and dark centre; the Sparrow Tongue (the Knot-grass) to its small acute leaves; and the Lark’s Spur, Heel, Toe, or Claw (Delphinium) to its projecting nectary. Chickweed and Duckweed have been so called from being favourite food for poultry.

“The Crow has given its name to a greater number of plants than any other bird. The Ranunculus is the Coronopus or Crow Foot of Dioscorides, the Geranium pratense is the Crowfoot Crane’s Bill, the Lotus corniculatus is called Crow Toes, the Daffodil and the Blue-bell both bear the name of Crow Bells, the Empetrum nigrum is the Crow Berry, Allium vineale is Crow Garlick, Scilla nutans, Crow Leeks, and the Scandix Pecten, Crow Needles.

“The Hen has a few plants named after it, the greater and lesser Hen Bits (Lamium amplexicaule and Veronica hederifolia); the Hen’s Foot (Caucalis daucoides), so called from the resemblance of its leaves to a hen’s claw; and Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger), which seems to have derived its name from the baneful effects its seeds have upon poultry.

Plants connected with Animals.

“The Ass has named after it the Ass Parsley (Æthusa Cynapium), and the Ass’s Foot, the Coltsfoot, Tussilago Farfara. William Coles says that “if the Asse be oppressed with melancholy, he eates of the Herbe Asplenion or Miltwaste, and eases himself of the swelling of the spleen.” D. C. Franciscus Paullini has given, in an old work, an account of three Asses he met in Westphalia, which were in the habit of intoxicating themselves by eating white Henbane and Nightshade. These four-footed drunkards, when in their cups, strayed to a pond, where they pulled themselves together with a dip and a draught of water.

Legend of the Donkey and the Plant

“The same author relates another story. A miller of Thuringia [Germany] had brought meal with his nine Asses into the next district. Having accepted the hospitality of some boon companions, he left his long-eared friends to wander around the place and to feed from the hedgerows and public roads. There they chanced to find a quantity of Thistles that had been cut, and other food mixed with Hemlock, and at once devoured the spoil greedily and confidently. At dusk, the miller, rising to depart, was easily detained by his associates, who cried out that the road was short, and that the moon, which had risen, would light him better than any torch. Meanwhile, the Asses, feeling the Hemlock’s power in their bodies, fell down on the public road, being deprived of all motion and sensation. At length, about midnight, the miller came to his Asses, and thinking them to be asleep, lashed them vigorously. But they remained motionless, and apparently dead. The miller, much frightened, now besought assistance from the country-folks, but they were all of one opinion, that the Asses were dead, and that they should be skinned the next day, when the cause of such a sudden death could be inquired into. “Come,” said he, “if they are dead, why should I worry myself about them—let them lie. We can do no good. Come, my friends, let us return into the inn—to-morrow you will be my witnesses.” Meanwhile the skinners were called; and, after looking at the Asses, one of them said, “Do you wish, miller, that we should take their skins off; or would you be disposed, if we restored the beasts to life, to give us a handsome reward? You see they are quite in our power. Say what you wish, and it shall be done, miller.” “Here is my hand,” replied the miller, “and I pledge my word that I will give you what you wish, if you restore them to life.” The skinner, smiling, caught hold of the whip, and lashing the beasts with all his might, roused all from their lethargic condition. The rustics were confounded. “O! you foolish fellows,” said he, “look at this herb (showing them some Hemlock), how profusely it grows in this neighbourhood. Do you not know that Hemlock causes Asses to fall into a profound sleep?” The rustics, flocking together under a Lime-tree, as rustics do, made there and then a law that whosoever should discover, in field or garden, or anywhere else, that noxious plant, he should pluck it quickly, in order that men and beasts might be injured by it no more.

The Bear has given its name to several English plants. The Primula Auricula, on account of the shape of its leaves, is called Bear’s Ears; the Helleborus fœtidus, for a similar reason, is known as Bears Foot; Meum athamanticum is Bear’s-wort; Allium ursinum, Bear’s Garlic; and Arctostaphylos uva ursi, Bear’s Berry, or Bear’s Bilberry; the three last plants being favourite food of Bears.

- Acanthus mollis – Acanthus*

Image Credit: Bluestone Perennials

“The Acanthus used at one time to be called Bear’s Breech, but the name has for some unaccountable reason been transferred to the Cow Parsnip, Heracleum Sphondylium. In Italy the name of Branca orsina is given to the Acanthus. This plant was considered by Dioscorides a cure for burns. Pliny says that Bear’s grease had the same property. De Gubernatis states that two Indian plants, the Argyreia argentea and the Batatas paniculata, bear Sanscrit names signifying “Odour pleasing to Bears.”

The Bull has given its name to some few plants. Tussilago Farfara, generally called Coltsfoot, is also known as Bull’s-Foot; Centaurea nigra is Bull’s-weed; Verbascum Thapsus is Bullock’s Lungwort, having been so denominated on account of its curative powers, suggested, on the Doctrine of Signatures, by the similarity of its leaf to the shape of a dewlap. The purple and the pale spadices of Arum maculatum are sometimes called Bulls and Cows. The Great Daisy is Ox-Eye; the Primula elatior, Ox-Lip; the Helminthia echioides, Ox-Tongue; and the Helleborus fætidus, Ox-Heel. The Antirrhinum and Arum maculatum are, from their resemblance in shape, respectively known as Calf’s Snout and Calf’s Foot.

Cats have several representative plants. From its soft flower-heads, the Gnaphalium dioicum is called Cat’s Foot; from the shape of its leaves, the Hypochæris maculata is known as Cat’s Ear; the Ground Ivy, also from the shape of its leaves, is Cat’s Paw; two plants are known as Cat’s Tail, viz., Typha latifolia and Phleum pratense. Euphorbia helioscopia, on account of its milky juice, is Cat’s Milk; and, lastly, Nepeta cataria is denominated Cat-Mint, because, as Gerarde informs us in his ‘Herbal,’ “Cats are very much delighted herewith: for the smell of it is so pleasant unto them, that they rub themselves upon it, and wallow or tumble in it, and also feed on the branches very greedily.” We are also told by another old writer that Cats are amazingly delighted with the root of the plant Valerian; so much so, that, enticed by its smell, they at once run up to it, lick it, kiss it, jump on it, roll themselves over it, and exhibit almost uncontrollable signs of joy and gladness. There is an old rhyme on the liking of Cats for the plant Marum, which runs as follows:—

The Cow has given its name to a whole series of plants: its Berry is Vaccinium Vitis idæa, its Cress, Lepidium campestre, its Parsley or Weed, Chærophyllum sylvestre, its Parsnip, Heracleum Sphondylium, its Wheat, Melampyrum. The Quaking Grass, Briza media, is known as Cow Quake, from an idea that cattle are fond of it; and the Water Hemlock (Cicuta virosa) has the opprobrious epithet of Cow Bane applied to it, from its supposed baneful effect upon oxen. The Primula veris is the Cowslip.

In Norway is to be found the herb Ossifrage—a kind of Reed which is said to have the remarkable power of softening the bones of animals; so much so, that if oxen eat it, their bones become so soft that not only are the poor beasts rendered incapable of walking, but they can even be rolled into any shape. They are not said to die however. Fortunately they can be cured, if the bones are exhibited to them of another animal killed by the eating of this plant. It is most wonderful, however, that the inhabitants make a medicine for cementing bones from this very herb.

There are several plants dedicated to man’s faithful friend. Dog’s Bane (Apocynum) is a very curious plant: its bell-shaped flowers entangle flies who visit the flower for its honey-juice, so that in August, when full blown, the corolla is full of their dead bodies. Although harmless to some persons, yet it is noxious to others, poisoning and creating swellings and inflammations on certain people who have only trod on it. Gerarde describes it as a deadly and dangerous plant, especially to four-footed beasts; “for, as Dioscorides writes, the leaves hereof, mixed with bread, and given, kill dogs, wolves, foxes, and leopards.” Dog’s Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomila) is a spurious or wild kind of Chamomile. Dog Grass (Triticum caninum) is so called because Dogs take it medicinally as an aperient. Dog’s Mercury (or Dog’s Cole) is a poisonous kind, so named to distinguish it from English Mercury. Dog’s Nettle is Galeopsis Tetrahit. Dog’s Orach (Chenopodium Vulvaria), is a stinking kind. Dog’s Parsley (Æthusa Cynapium), a deleterious weed, also called Fool’s Parsley and Lesser Hemlock. Dog Rose (Rosa canina) is the common wilding or Canker Rose; the ancients supposed the root to cure the bite of a mad Dog, it having been recommended by an oracle for that purpose; hence the Romans called it Canina; and Pliny relates that a soldier who had been bitten by a mad Dog, was healed with the root of this shrub, which had been indicated to his mother in a dream. Dog’s Tail Grass (Cynosurus cristatus) derives its name from its spike being fringed on one side only. Dog Violet (Viola canina) is so-called contemptuously because scentless. Dog’s Tongue, or Hound’s Tongue (Cynoglossum officinale) derived its name from the softness of its leaf, and was reputed to have the magical property of preventing the barking of Dogs if laid under a person’s feet. Dog Wood (Cornus sanguinea) is the wild Cornel; and Dog Berries the fruit of that herb, which was also formerly called Hound’s Tree. Dr. Prior thinks that this name has been misunderstood, and that it is derived from the old English word dagge, or dagger, which was applied to the wood because it was used for skewers by butchers. The ancient Greeks knew a plant (supposed to be a species of Antirrhinum) which they called Cynocephalia (Dog’s Head), as well as Osiris; and to this plant Pliny ascribes extraordinary properties. As a rule, the word “Dog,” when applied to any plant, implies contempt.

After the Fox has been named, from its shape, the Alopecurus pratensis, Fox-Tail-grass; and the Digitalis has been given the name of Fox-Glove.

The Goat has its Weed (Ægopodium Podagraria), and has given its name to the Tragopogon pratensis, which, on account of its long, coarse pappus, is called Goat’s Beard. Caprifolium, or Goat’s Leaf, is a specific name of the Honeysuckle, given to it by the old herbalists, because the leaf, or more properly the stem, climbs and wanders over high places where Goats are not afraid to tread.

A species of Sow Thistle, the Sonchus oleraceus, is called the Hare’s Palace, from a superstitious notion that the Hare derives shelter and courage from it. Gerarde calls it the Hare’s Lettuce, a name given to it by Apuleius, because, when the Hare is fainting with heat or fatigue, she recruits her failing strength with it. Dr. Prior gives the following extracts from old authors respecting this curious tradition. Anthony Askam says, “yf a Hare eate of this herbe in somer, when he is mad, he shal be hole.” Topsell also tells us in his ‘Natural History,’ p. 209, that “when Hares are overcome with heat, they eat of an herb called Lactuca leporina, that is, the Hare’s-lettuce, Hare’s-house, Hare’s-palace; and there is no disease in this beast, the cure whereof she does not seek for in this herb.” This plant is sometimes called Hare’s Thistle. Bupleurum rotundifolium is termed Hare’s Ear, from the shape of its leaves, as is also Erysimum orientale. Trifolium arvense is Hare’s Foot, from the soft grey down which surrounds the blossoms resembling the delicate fur of the Hare’s foot. Both Lagurus oratus, and the flowering Rush, Eriophorum vaginatum, are called Hare’s Tail, from the soft downy inflorescence.

Melilotus officinalis is Hart’s Clover; Scolopendrium vulgare, Hart’s Tongue; Plantago Coronopus, Hart’s Horn; Scirpus cæspitosus, Deer’s or Hart’s Hair; Rhamnus catharticus, Hart’s or Buck Thorn (Spina cervina); and Tordylium maximum, Hart Wort, so called because, as Dioscorides tells us, the juice of the leaves was given to Roes in order that they might speedily be delivered of their young. According to Pliny, the Roman matrons used to employ it for the same purpose, having been “taught by Hindes that eate it to speade their delivery, as Aristotle did declare it before.”

The Raspberry is still sometimes called by its ancient name of Hindberry; and the Teucrium Scorodonia is known as Hind-heal, from an old tradition that it cures Deer when bitten by venomous serpents. The Dittany is said to have the same extraordinary effect on wounded Harts as upon Goats (see Dittany, Part II.).

Numerous indeed are the plants named after the Horse, either on account of the use they are put to, the shape of their foliage, &c., their large size, or the coarseness of their texture. Inula Helenium is Horse-heal, a name attached to the plant by a double blunder of Inula for hinnula, a Colt, and Helenium, for heal or heel; employed to heal Horses of sore heels, &c. Vicia Faba is the Horse Bean; Teucrium Chamædrys, the Germander, is called Horse Chire, from its springing up after Horse-droppings. Melampyrum sylvaticum is the Horse Flower, so called from a verbal error. The Alexandrian Laurel was formerly called Horse Tongue. Tussilago Farfara, from the shape of its leaf, is termed Horse Hoof. Centaurea nigra is Horse Knob. Another name for Colt’s Foot is Horse Foot; and we have Horse Thistle, Mint, Mushroom, Parsley, Thyme, and Radish. The Dutch Rush, Equisetum, is called Horse Tail, a name descriptive of its shape; Hippocrepis comosa is known as the Horse-shoe Vetch, from the shape of the legumes; and, lastly, the Œnanthe Phellandrium is the Horse Bane, because, in Sweden, it is supposed to give Horses the palsy. In Mexico, the Rattle Grass is said to instantly kill Horses who unfortunately eat it. The Indians call the Oleander Horse’s Death, and they name several plants after different parts of the Horse. In connection with Horses, we must not forget to mention the Moonwort, which draws the nails out of the Horses’ shoes, and of which Culpeper writes: “Moonwort is an herb which they say will open locks and unshoe such Horses as tread upon it; this some laugh to scorn, and those no small fools neither; but country people that I know, call it Unshoe-the-Horse. Besides, I have heard commanders say that, on White Down, in Devonshire, near Tiverton, there were found thirty horse-shoes, pulled off from the Earl of Essex’s horses, being then drawn up in a body, many of them being newly shod, and no reason known, which caused much admiration, and the herb described usually grows upon heaths.” In Italy, the herb Sferracavallo is deemed to have the power of unshoeing Horses out at pasture. The Mouse-ear, or Herba clavorum, is reputed to prevent blacksmiths hurting horses when being shod. The Scythians are said to have known a plant, called Hippice, which, when given to a Horse, would enable him to travel for some considerable time without suffering either from hunger or thirst. Perhaps this is the Water Pepper, which, according to English tradition, has the same effect if placed under the saddle.

The humble Hedgehog has suggested the name of Hedgehog Parsley for Caucalis daucoides, on account of its prickly burs.

In a previous chapter, a full description has been given of the Barometz, that mysterious plant of Tartary, immortalised by Darwin as the Vegetable Lamb. From the shape of its leaf, the Plantago media has gained the name of Lamb’s Tongue; from its downy flowers, the Anthyllis vulneraria is called Lamb’s Toe; either from its being a favourite food of Lambs, or because it appears at the lambing season, the Valerianella olitoria is known as Lamb’s Lettuce; and the Atriplex patula is called Lamb’s Quarters.

The Leopard has given its name to the deadly Doronicum Pardalianches (from the Greek Pardalis, a Leopard, and ancho, to strangle); hence our name of Leopard’s Bane, because it was reputed to cause the death of any animal that ate it, and it was therefore formerly mixed with flesh to destroy Leopards.

The Lion, according to Gerarde, claimed several plants. The Alchemilla vulgaris, from its leaf resembling his foot, was called Lion’s Foot or Paw; a plant, called Leontopetalon by the Greeks, was known in England as Lion’s Turnip or Lion’s Leaf; and two kinds of Cudweed, Leontopodium and L. parvum, bore the name of Lion’s Cudweed, from their flower-heads resembling a Lion’s foot. The Leontopodium has been identified with the Gnaphalium Alpinum, the Filago stellata, the Edelweiss of the Germans, and the Perlière des Alpes of the French. De Gubernatis points out that, inasmuch as the Lion represents the Sun, the plants bearing the Lion’s name are essentially plants of the Sun. This is particularly noticeable in the case of the Dandelion (Dent de Lion) or Lion’s Tooth. In Geneva, Switzerland, children form a chain of these flowers, and holding it in their hands, dance in a circle; a German name for it is Sonneswirbel (Solstice), as well as Solsequium heliotropium. The Romans saw in the flower of the Helianthus a resemblance to a Lion’s mouth. In the Orobanche or Broom Rape (the Sonnenwurz, Root of the Sun, of the Germans) some have seen the resemblance to a Lion’s mouth and foot; it was called the Lion’s Pulse or Lion’s Herb, and was considered an antidote to poison.

The tiny Mouse, like the majestic Lion, is represented in the vegetable kingdom by several plants. From the shape of the leaves, Hieracium Pilosella is known as Mouse Ear, Cerastium vulgare, Mouse Ear Chickweed, and Myosotis palustris, or Forget-Me-Not, Mouse Ear Scorpion Grass. Myosurus minimus, from the shape of its slender seed-spike, is called Mouse Tail; and Alopecurus agrestis, Mouse Tail Grass. Hordeum marinum is Mouse Barley.

Swine plants are numerous. We have the Swine Bane, Sow Bane, or Pig Weed (Chenopodium rubrum), a herb which, according to Parkinson, was “found certain to kill Swine.” The Pig Nut (Bunium flexuosum) is so called from its tubers being a favourite food of Pigs. Sow Bread (Cyclamen Europæum) has obtained its name for a similar reason; and Swine’s Grass (Polygonum aviculare) is so called because Swine are believed to be fond of it. Hyoseris minima is Swine Succory, and Senebiera Coronopus, Swine’s Cress. For possession of the Dandelion, the Pig enters the lists with the Lion, and claims the flower as the Swine’s Snout, on account of the form of its receptacle. According to Du Bartas, Swine, when affected with the spleen, seek relief by eating the Spleenwort or Miltwaste (Asplenium Ceterach),

De Gubernatis states that the god Indra is thought to have taken the form of a Goat, and he gives a long list of Indian plants named after Sheep and Goats. The Ram, He-Goat, and Lamb, called Mesha, also give their names, in Sanscrit, to different plants. In England, Rumex Acetosella is Sheep’s Sorrel, Chærophyllum temulum Sheep’s Parsley, Jasione montana Sheep’s-Bit-Scabious, and Hydrocotyle vulgaris, or White Rot, Sheep’s Bane, from its character of poisoning Sheep.

The Squirrel, although a denizen of the woods, only claims one plant, Hordeum maritimum, which, from the shape of its flower-spike, has obtained the name of Squirrel Tail.

The Elephant has a whole series of Indian trees and plants dedicated to him, which are enumerated by De Gubernatis; the Bignonia suaveolens is called the Elephant’s Tree; and certain Cucumbers, Pumpkins, and Gourds are named after him. [Elephsnt Ears]

The Wolf, in India, gives its name to the Colypea hernandifolia, and Wolf’s Eye is a designation given to the Ipomœa Turpethum. Among the Germans, the Wolf becomes, under the several names of Graswolf, Kornwolf, Roggenwolf, and Kartoffelwolf, a demon haunting fields and crops. In our own country, the Euphorbia, from its acrid, milky juice, is called Wolf’s Milk; the Lycopodium clavatum is the Wolf’s Claw, and the Aconitum Lycoctonum is Wolf’s Bane, a name it obtained in olden times when hunters were in the habit of poisoning with the juice of this plant the baits of flesh they laid for Wolves.

There are several plants bearing, in some form or other, the appellation of Dragon. The common Dragon (Arum Dracunculus) is, as its name implies, a species of Arum, which sends up a straight stalk about three feet high, curiously spotted like the belly of a serpent. The flower of the Dragon plant has such a strong scent of carrion, that few persons can endure it, and it is consequently usually banished from gardens. Gerarde describes three kinds of Dragons, under the names of Great Dragon, Small Dragon, and Water Dragon: these plants all have homœopathic qualities, inasmuch as although they are by name at least vegetable reptiles, yet, according to Dioscorides, all who have rubbed the leaves or roots upon their hands, will not be bitten by Vipers. Pliny also says that Serpents will not come near anyone who carries a portion of a Dragon plant with him, and that it was a common practice in his day to keep about the person a piece of the root of this herb. Gerarde tells us that “the distilled water has vertue against the pestilence or any pestilentiall fever or poyson, being drunke bloud warme with the best treacle or mithridate.” He also says that the smell of the flowers is injurious to women who are about to become mothers. The Green Dragon (Arum Dracontium), a native of China, Japan, and America, possesses a root which is prescribed as a very strong emmenagogue. There is a species of Dragon which grows in the morasses about Magellan’s Strait, whose flowers exhibit the appearance of an ulcer, and exhale so strong an odour of putrid flesh, that flesh-flies resort to it to deposit their eggs. Another Dragon plant is the Dracontium polyphyllum, a native of Surinam and Japan, where they prepare a medicine from the acrid roots, which they call Konjakf, and esteem as a great emmenagogue: it is used there to procure abortion. Dracontium fœtidum, Fetid Dragon, or Skunk-weed, flourishes in the swamps of North America, and has obtained its nickname from its rank smell, resembling that of a Skunk or Pole-cat. Dragon’s Head (Dracocephalum) is a name applied to several plants. The Moldavian Dragon’s Head is often called Moldavian or Turk’s Balm. The Virginian Dragon’s Head is named by the French, La Cataleptique, from its use in palsy and kindred diseases. The Canary Dragon’s Head, a native of the Canary Islands, is called (improperly) Balm of Gilead, from its fine odour when rubbed. The old writers called it Camphorosma and Cedronella, and ascribed to it, as to other Dragon plants, the faculty of being a remedy for the bites and stings of venomous beasts, as well as for the bites of mad Dogs. The Tarragon (Artemisia Dracunculus), “the little Dragon,” is the Dragon plant of Germany and the northern nations, and the Herbe au Dragon of the French. The ancient herbalists affirmed that the seed of the Flax put into a Radish-root or Sea Onion, and so set, would bring forth the herb Tarragon. The Snake Weed was called by the ancients, Dragon and Little Dragon, and the Sneezewort, Dragon of the Woods. The Snap-dragon appears to have been so named merely from the shape of its corolla, but in many places it is said to have a supernatural influence, and to possess the power of destroying charms.

Snakes are represented by the Fritillaria Meleagris, which is called Snake’s Head, on account of its petals being marked like Snakes’ scales. The Sea Grass (Ophiurus incurvatus) is known as Snake’s Tail, and the Bistort (Polygonum Bistorta) is Snake Weed.

Vipers have the Echium vulgare dedicated to them under the name of Viper’s Bugloss, a plant supposed to cure the bite of these reptiles; and the Scorzonera edulis, or Viper’s Grass, a herb also considered good for healing wounds caused by Vipers.

The Scorpion finds a vegetable representative in the Myosotis, or Scorpion Grass, so named from its spike resembling a Scorpion’s Tail.

It is not surprising to find that Toads and Frogs, living as they do among the herbage, should have several plants named after them. The Toad, according to popular superstition, was the impersonation of the Devil, and therefore it was only fit that poisonous and unwholesome Fungi should be called Toad Stools, the more so as there was a very general belief that Toads were in the habit of sitting on them:—

Growing in damp places, haunted by Toads croaking and piping to one another, the Equisetum limosum, with its straight, fistulous stalks, has obtained the name of Toad Pipe. The Linaria vulgaris, from its narrow Flax-like leaves, is known as Toad Flax, from a curious mistake of the old herbalists who confounded the Latin words bubo and bufo.

Frogs claim as their especial plants the Frog Bit (Morsus ranæ), so called because Frogs are supposed to eat it; Frog’s Lettuce (Potamogeton densus); Frog Grass (Salicornia herbacea); and Frog Foot, a name originally assigned to the Vervain (the leaf of which somewhat resembles a Frog’s foot); but now transferred to the Duck Meat, Lemna.

Bees are recognised in the Delphinium grandiflorum, or Bee Larkspur; the Galeopsis Tetrahit, or Bee Nettle; the Ophrys apifera, or Bee Orchis; and the Daucus Carota, or Bee’s Nest.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.