.

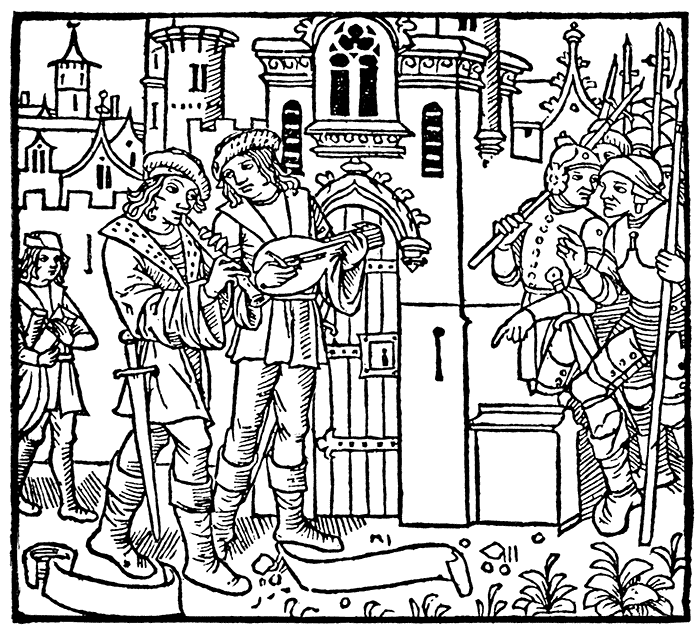

.| BIBLE, HEINRICH QUENTEL. | (COLOGNE, 1480.) |

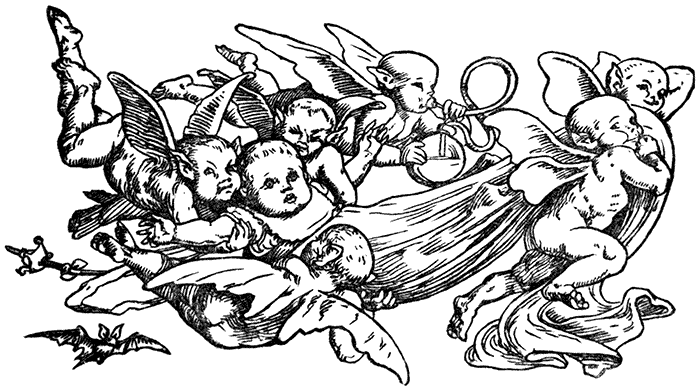

| ALBRECHT DÜRER, “KLEINE PASSION.” | (NUREMBERG, 1512.) |

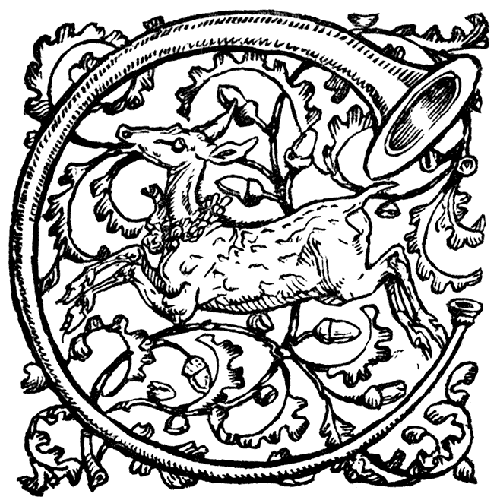

| ALBRECHT DÜRER. | (NUREMBERG, HEINRICH STEYNER, 1513.) |

| DESIGNED BY ALBRECHT DÜRER. | (NUREMBERG, 1523.) |

| HOLBEIN. THE PLOUGHMAN. |

“DANCE OF DEATH.” (LYONS, 1538.) |

| AMBROSE HOLBEIN. | “DAS GANTZE NEUE TESTAMENT,” ETC. (BASEL, 1523.) |

GERMAN SCHOOL.XVIth CENTURY.

| HANS BURGMAIR. | “DIE MEERFAHRT ZU VILN ONERKANNTEN INSELN UND KUNIGREICHEN.” (AUGSBURG, 1509.) |

GERMAN SCHOOL.XVIth CENTURY.

| HANS SEBALD BEHAM. | “DAS PAPSTTHUM MIT SEINEN GLIEDERN.” (NUREMBERG, HANS WANDEREISEN, 1526.) |

William Blake

We now come to a designer of a very different type, a type, too, of a new epoch, whatever resemblance in style and method there may be in his work to that of his contemporaries. William Blake is distinct, and stands alone. A poet and a seer, as well as a designer, in him seemed to awake something of the spirit of the old illuminator. He was not content to illustrate a book by isolated copper or steel plates apart from the text, although in his craft as engraver he constantly carried out the work of others. When he came to embody his own thoughts and dreams, he recurred quite spontaneously to the methods of the maker of the MS. books. He became his own calligrapher, illuminator and miniaturist, while availing himself of the copper-plate (which he turned into a surface printing block) and the printing press for the reproduction of his designs, and in some cases for producing them in tints. His hand-coloured drawings, the borderings and devices to his own poems, will always be things by themselves.

His treatment of the resources of black and white, and sense of page decoration, may be best judged perhaps by a reference to his “Book of Job,” which contains a fine series of suggestive and imaginative designs. We seem to read in Blake something of the spirit of the Mediæval designers, through the sometimes mannered and semi-classic forms and treatment, according to the taste of his time; while he embodies its more daring aspiring thoughts, and the desire for simpler and more humane conditions of life. A revolutionary fire and fervour constantly breaks out both in his verse and in his designs, which show very various moods and impulses, and comprehend a wide range of power and sympathy. Sometimes mystic and prophetic, sometimes tragic, sometimes simple and pastoral.

Blake, in these mixed elements, and the extraordinary suggestiveness of his work and the freedom of his thought, seems nearer to us than others of his contemporaries. In his sense of the decorative treatment of the page, too, his work bears upon our purpose. In writing with his own hand and in his own character the text of his poems, he gained the great advantage which has been spoken of—of harmony between text and illustration. They become a harmonious whole, in complete relation. His woodcuts to Phillip’s “Pastoral,” though perhaps rough in themselves, show what a sense of colour he could convey, and of the effective use of white line.

.

.  .

.

Children’s books and so-called children’s books hold a peculiar position. They are attractive to designers of an imaginative tendency, for in a sober and matter-of-fact age they afford perhaps the only outlet for unrestricted flights of fancy open to the modern illustrator, who likes to revolt against “the despotism of facts.” While on children’s books, the poetic feeling in the designs of E. V. B. may be mentioned, and I mind me of some charming illustrations to a book of Mr. George Macdonald’s, “At the Back of the North Wind,” designed by Mr. Arthur Hughes, who in these and other wood engraved designs shows, no less than in his paintings, how refined and sympathetic an artist he is. Mr. Robert Bateman, too, designed some charming little woodcuts, full of poetic feeling and controlled by unusual taste. They were used in Macmillan’s “Art at Home” series, though not, I believe, originally intended for it.

There is no doubt that the opening of Japanese ports to Western commerce, whatever its after effects—including its effect upon the arts of Japan itself—has had an enormous influence on European and American art. Japan is, or was, a country very much, as regards its arts and handicrafts with the exception of architecture, in the condition of a European country in the Middle Ages, with wonderfully skilled artists and craftsmen in all manner of work of the decorative kind, who were under the influence of a free and informal naturalism.JAPANESE ILLUSTRATION. Here at least was a living art, an art of the people, in which traditions and craftsmanship were unbroken, and the results full of attractive variety, quickness, and naturalistic force. What wonder that it took Western artists by storm, and that its effects have become so patent, though not always happy, ever since. We see unmistakable traces of Japanese influences, however, almost everywhere—from the Parisian impressionist painter to the Japanese fan in the corner of trade circulars, which shows it has been adopted as a stock printers’ ornament. We see it in the sketchy blots and lines, and vignetted naturalistic flowers which are sometimes offered as page decorations, notably in American magazines and fashionable etchings. We have caught the vices of Japanese art certainly, even if we have assimilated some of the virtues.

ARTHUR HUGHES.

FROM “STORIES FOR CHILDREN,” BY FRANCES M. PEARD. (ALLEN, 1896.)

| FROM “STORIES FOR CHILDREN,” BY F. M. PEARD. | (ALLEN, 1896.) |

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

.

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.