Image Credit: Detail of a Map from the Student Bible Atlas by Tim Dowley:

On the above map, Mesopotamia is the upper area that is colored dark yellow. Most scholars believe that Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden were located in the Mesopotamian area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Abraham. the Father of the Israelites was originally fom Ur, which is marked near the Persian Gulf. Abraham and his immediate family worshipped one God, the God who created the believed created the world, including the Garden of Eden, early Biblical History reflects that there was a continual stuggle against the polytheistic religions and their idols. In this post, I will tell you a bit about the polytheistic deities that were worshipped in ancient Mesopotamia.

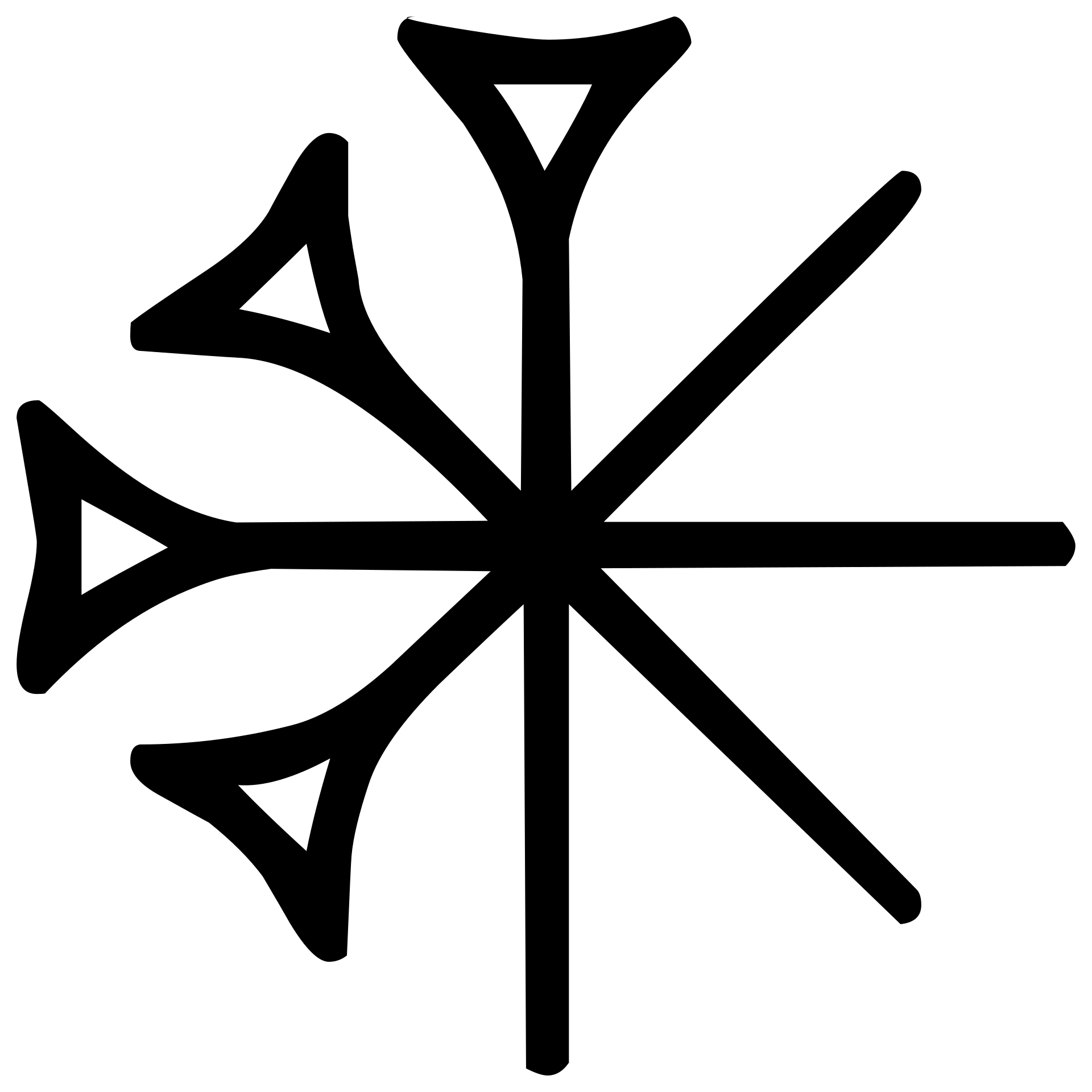

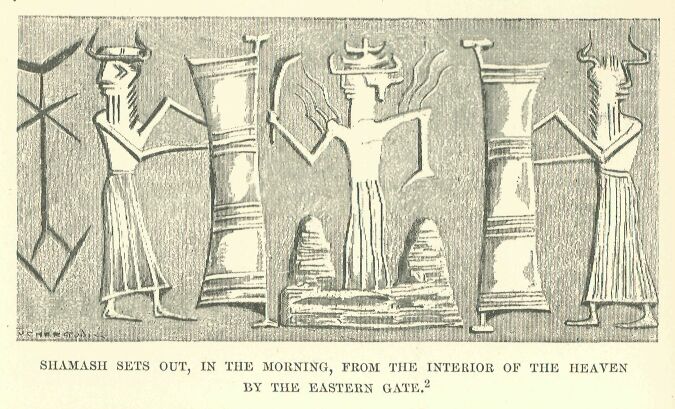

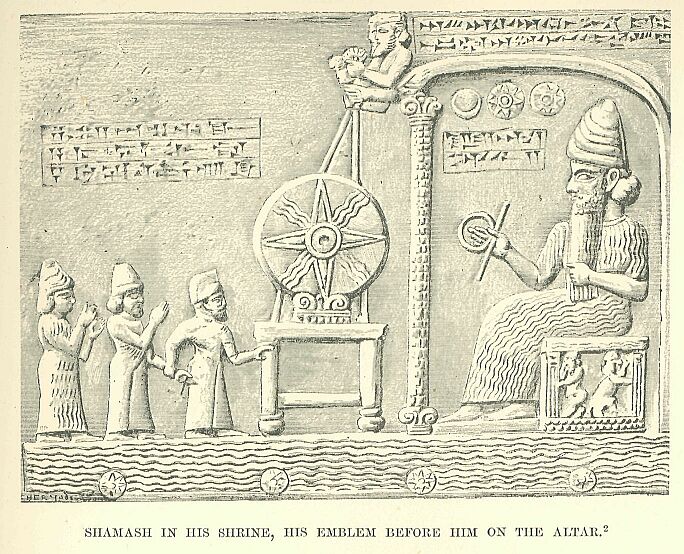

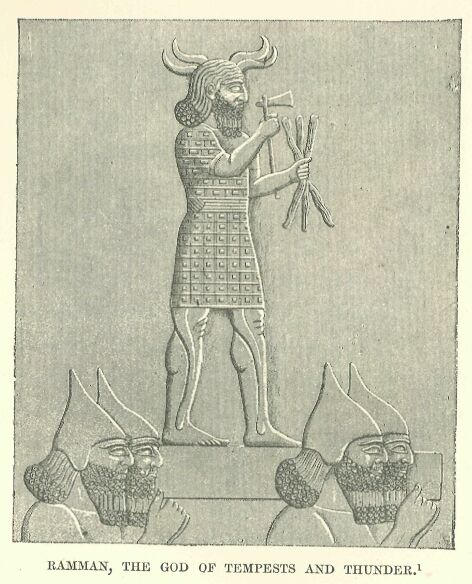

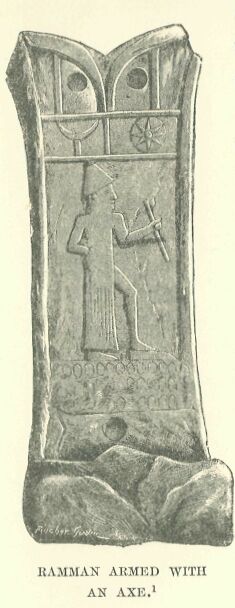

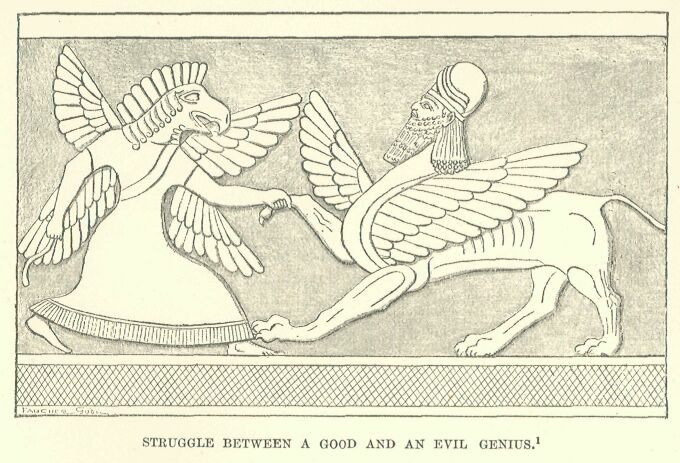

“Deities were almost always depicted wearing horned caps,[6][7] consisting of up to seven superimposed pairs of ox-horns.[8] They were also sometimes depicted wearing clothes with elaborate decorative gold and silver ornaments sewn into them.[7]he

“The ancient Mesopotamians believed that their deities lived in Heaven,[9] but that a god’s statue was a physical embodiment of the god himself.[9][10] As such, cult statues were given constant care and attention[11][9] and a set of priests were assigned to tend to them.[12] These priests would clothe the statues[10] and place feasts before them so they could “eat”.[11][9] A deity’s temple was believed to be that deity’s literal place of residence.[13] The gods had boats, full-sized barges which were normally stored inside their temples[14] and were used to transport their cult statues along waterways during various religious festivals.[14]

“The gods also had chariots, which were used for transporting their cult statues by land.[15] Sometimes a deity’s cult statue would be transported to the location of a battle so that the deity could watch the battle unfold.[15] The major deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon were believed to participate in the “assembly of the gods”,[6] through which the gods made all of their decisions.[6] This assembly was seen as a divine counterpart to the semi-democratic legislative system that existed during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BC – c. 2004 BC).[6] …T

The Number Seven

The number seven was extremely important in ancient Mesopotamian cosmology.[41][42] In Sumerian religion, the most powerful and important deities in the pantheon were sometimes called the “seven gods who decree”:[43] An, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna.[44] Many major deities in Sumerian mythology were associated with specific celestial bodies:[45] Inanna was believed to be the planet Venus,[46][47] Utu was believed to be the Sun,[48][47] and Nanna was the Moon.[49][47] However, minor deities could be associated with planets too, for example Mars was sometimes called Simut,[50] and Ninsianna was a Venus deity distinct from Inanna in at least some contexts.[51]

An

Enki

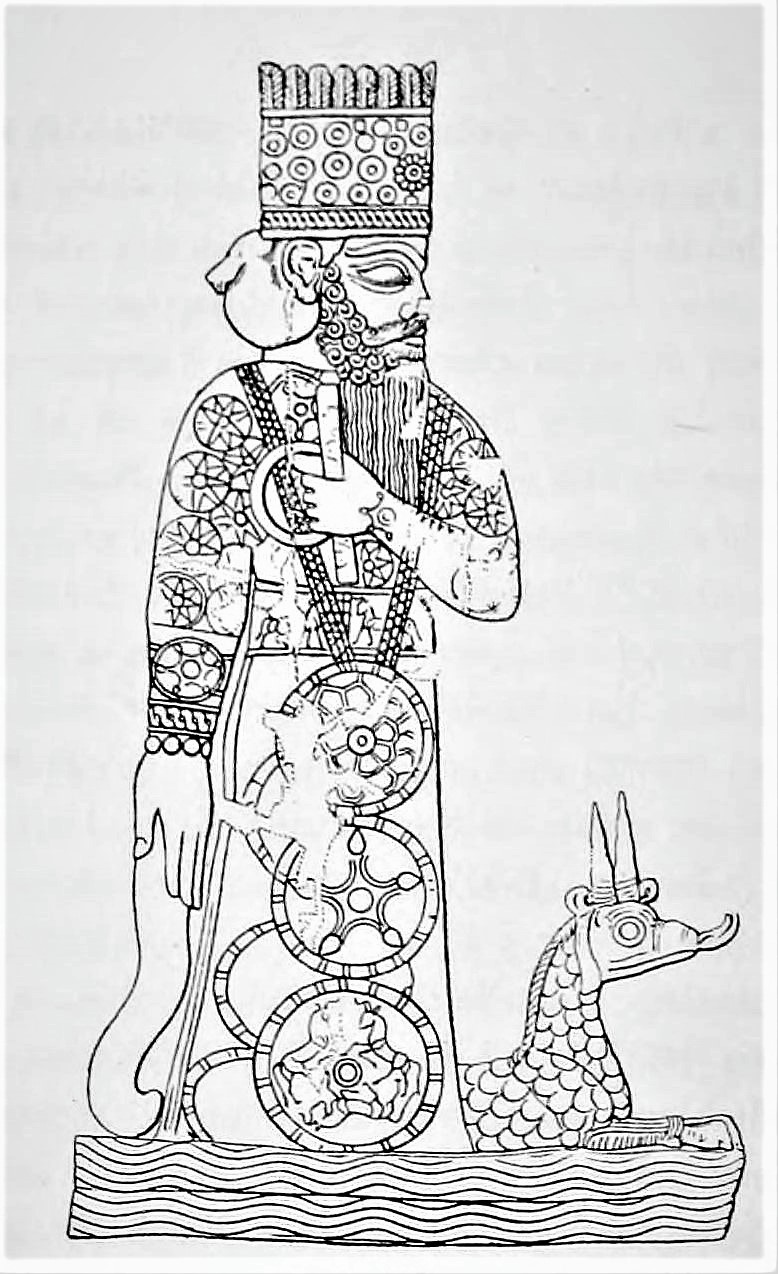

“Enki, later known as Ea, and also occasionally referred to as Nudimmud or Ninšiku, was the god of the subterranean freshwater ocean,[74] who was also closely associated with wisdom, magic, incantations, arts, and crafts.[74] He was either the son of An, or the goddess Nammu,[74] and is the former case the twin brother of Ishkur.[74] His wife was the goddess Damgalnuna (Ninhursag)[74] and his children include the gods Marduk, Asarluhi, Enbilulu, the sage Adapa, and the goddess Nanshe.[74] His sukkal, or minister, was the two-faced messenger god Isimud.[74] Enki was the divine benefactor of humanity,[74] who helped humans survive the Great Flood.[74] In Enki and the World Order, he organizes “in detail every feature of the civilised world.”[74] In Inanna and Enki, he is described as the holder of the sacred mes, the tablets concerning all aspects of human life.[74] He was associated with jasper.[63][73]

Marduk

“Marduk is the national god of the Babylonians.[76] The expansion of his cult closely paralleled the historical rise of Babylon[76][71] and, after assimilating various local deities, including a god named Asarluhi, he eventually came to parallel Enlil as the chief of the gods.[76][71] Some late sources go as far as omitting Enlil and Anu altogether, and state that Ea received his position from Marduk.[39] His wife was the goddess Sarpānītu.[76] wikiped

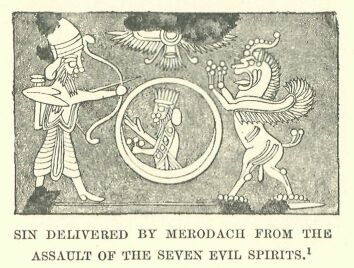

“the Mesopotamian god Marduk is also referred to as Merodach, with “Merodach” being considered an alternative name for him in the Bible and other texts; essentially, they are the same deity. ” Google ai

- Biblical reference: In the Bible, the name “Merodach” is used when referring to Marduk, particularly in the context of the Babylonian king “Evil-Merodach” (Amel-Marduk)

Marduk and Nanna are not the same god, but they are both important Mesopotamian gods:

The main Babylonian god, Marduk was the patron god of Babylon and the head of the Mesopotamian pantheon. He was a god of creation and destruction, and was associated with calamities like natural disasters. Marduk was also the god of justice, compassion, healing, regeneration, magic, and fairness.

Nannar

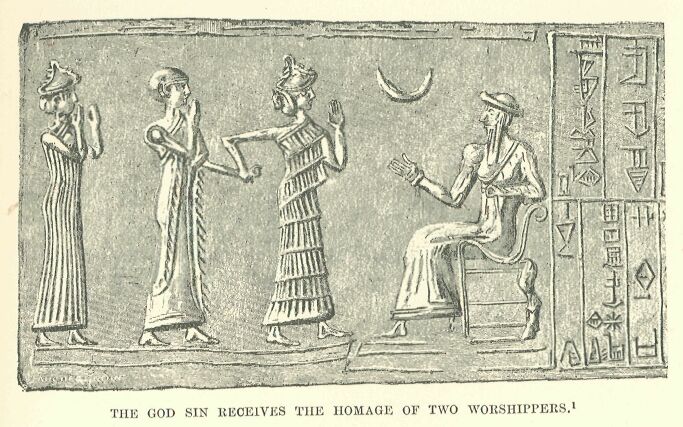

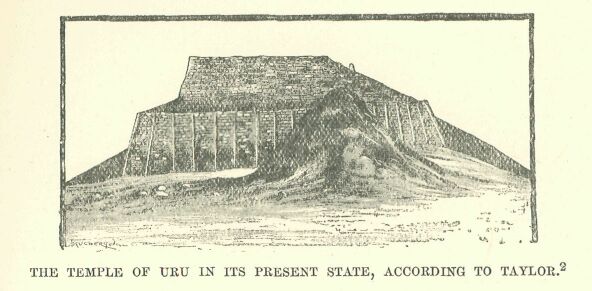

Nanna or Nannar is the god of the temple at Ur. He was called Sin by the Akkadians.

Nanna was the Moon god. Monday is named after him.

“Nanna, the Sumerian name for the moon god, may have originally meant only the full moon, whereas Su-en, later contracted to Sin, designated the crescent moon. At any rate, Nanna was intimately connected with the cattle herds that were the livelihood of the people in the marshes of the lower Euphrates River, where the cult developed. (The city of Ur, of the same region, was the chief centre of the worship of Nanna.) The crescent, Nanna’s emblem, was sometimes represented by the horns of a great bull. Nanna bestowed fertility and prosperity on the cowherds, governing the rise of the waters, the growth of reeds, the increase of the herd, and therefore the quantity of dairy products produced. His consort, Ningal, was a reed goddess. Each spring, Nanna’s worshipers reenacted his mythological visit to his father, Enlil, at Nippur with a ritual journey, carrying with them the first dairy products of the year. Gradually Nanna became more human: from being depicted as a bull or boat, because of his crescent emblem, he came to be represented as a cowherd.” Britannica

Sin or Nanna [Moon god] being delivered by Merodach from the assault of the Seven Evil Spirits.

Nanna – god of the Moon

“Nanna, Enzu or Zuen (“Lord of Wisdom”) in Sumerian, later altered as Suen and Sin in Akkadian,[90] is the ancient Mesopotamian god of the Moon.[49] He was the son of Enlil and Ninlil and one of his most prominent myths was an account of how he was conceived and how he made his way from the Underworld to Nippur.[49] A theological system where Nanna, rather than Enlil, was the king of gods, is known from a text from the Old Babylonian period;[91] in the preserved fragment Enlil, Anu, Enki and Ninhursag served as his advisers, alongside his children Utu and Inanna.[35] Other references to Nanna holding such a position are known from personal names and various texts, with some going as far as stating he holds “Anuship and Enlilship,” Wikipedia

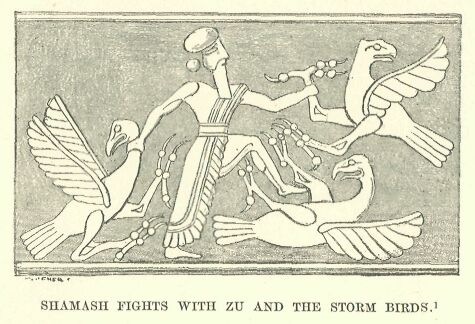

Shamash was the sun god in Mesopotamian and Akkadian religions:

As soon as he appeared he was hailed with the chanting of hymns: “O Sun, thou appearest on the foundation of the heavens,—thou drawest back the bolts which bar the scintillating heavens, thou openest the gate of the heavens! O Sun, thou raisest thy head above the earth,—Sun, thou extendest over the earth the brilliant vaults of the heavens.” The powers of darkness fly at his approach or take refuge in their mysterious caverns, for “he destroys the wicked, he scatters them, the omens and gloomy portents, dreams, and wicked ghouls—he converts evil to good, and he drives to their destruction the countries and men—who devote themselves to black magic.” In addition to natural light, he sheds upon the earth truth and justice abundantly; he is the “high judge” before whom everything makes obeisance, his laws never waver, his decrees are never set at naught. “O Sun, when thou goest to rest in the middle of the heavens—may the bars of the bright heaven salute thee in peace, and may the gate of heaven bless thee!—May Misharu, thy well-beloved servant, guide aright thy progress, so that on Rbarra, the seat of thy rule, thy greatness may rise, and that A, thy cherished spouse, may receive thee joyfully! May thy glad heart find in her thy rest!—May the food of thy divinity be brought to thee by her,—warrior, hero, sun, and may she increase thy vigour;—lord of Ebarra, when thou ap-proachest, mayest thou direct thy course aright!—-0 Sun, urge rightly thy way along the fixed road determined for thee,—O Sun, thou who art the judge of the land, and the arbiter of its laws!” G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3

Utu – Also called Shamash – god of the Sun

“Utu, later known as Shamash, is the ancient Mesopotamian god of the Sun,[92] who was also revered as the god of truth, justice, and morality.[93] He was the son of Nanna and the twin brother of Inanna. Utu was believed to see all things that happen during the day[93] and to aid mortals in distress.[93] Alongside Inanna, Utu was the enforcer of divine justice.[94 Wikipedia

]

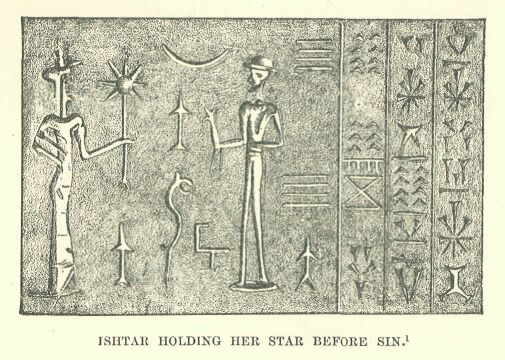

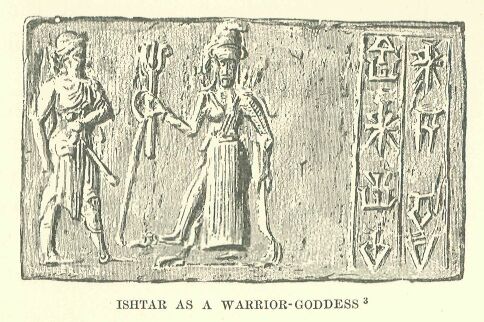

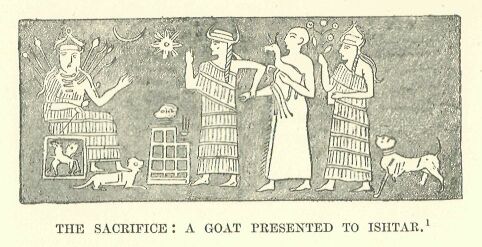

Ishtar – Venus – Evening and Morning Star

“Inanna, later known as Ishtar, is “the most important female deity of ancient Mesopotamia at all periods.”[95] She was the Sumerian goddess of love, sexuality, prostitution, and war.[97] She was the divine personification of the planet Venus, the morning and evening star.[46] Accounts of her parentage vary;[95] in most myths, she is usually presented as the daughter of Nanna and Ningal,[98] but, in other stories, she is the daughter of Enki or An along with an unknown mother.[95] The Sumerians had more myths about her than any other deity.[99][100] Many of the myths involving her revolve around her attempts to usurp control of the other deities’ domains.[101] Her most famous myth is the story of her descent into the Underworld,[102] in which she attempts to conquer the Underworld, the domain of her older sister Ereshkigal,[102] but is instead struck dead by the seven judges of the Underworld.[103][104][105] She is only revived due to Enki’s intervention[103][104][105] and her husband Dumuzid is forced to take her place in the Underworld.[106][107] Alongside her twin brother Utu, Inanna was the enforcer of divine justice.[94] Wikipedia

“It would appear that the triad had begun by having in the third place a goddess, Ishtar of Dilbat. Ishtar is the evening star which precedes the appearance of the moon, and the morning star which heralds the approach of the sun: the brilliance of its light justifies the choice which made it an associate of the greater heavenly bodies. “In the days of the past…. Ea charged Sin, Shamash, and Ishtar with the ruling of the firmament of heaven; he distributed among them, with Anu, the command of the army of heaven, and among these three gods, his children, he apportioned the day and the night, and compelled them to work ceaselessly.” G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3

Wives of the gods

“The gods of the triads were married, but their goddesses for the most part had neither the liberty nor the important functions of the Egyptian goddesses.** They were content, in their modesty, to be eclipsed behind the personages of their husbands, and to spend their lives in the shade, as the women of Asiatic countries still do. It would appear, moreover, that there was no trouble taken about them until it was too late—when it was desired, for instance, to explain the affiliation of the immortals. Anu and Bel were bachelors to start with. When it was determined to assign to them female companions, recourse was had to the procedure adopted by the Egyptians in a similar case: there was added to their names the distinctive suffix of the feminine gender, and in this manner two grammatical goddesses were formed….

“The wife of Ea was distinguished by a name which was not derived from that of her husband, but she was not animated by a more intense vitality than Anat or Belit: she was called Damkina, the lady of the soil, and she personified in an almost passive manner the earth united to the water which fertilized G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3

Ningirsu, the lord of the division of Lagash which was called Girsu, was identified with Ninib;

Inlil is Bel [Baal]

Ninursag is Beltis,

Inzu is Sin [Nannar] the Moon

Inanna is Ishtar, and so on with the rest. The cultus of each, too, was not a local cultus, confined to some obscure corner of the country; they all were rulers over the whole of Chaldæa, in the north as in the south, at Uruk, at Urn, at Larsam, at Nipur, even in Babylon itself. Inlil was the ruler of the earth and of Hades, Babbar was the sun, Inzu the moon, Inanna-Antmit the morning and evening star and the goddess or love, at a time when two distinct religious and two rival groups of gods existed side by side on the banks of the Euphrates . G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3

“Whether Sumerian or Semitic, the gods, like those of Egypt, were not abstract personages, guiding in a metaphysical fashion the forces of nature. Each of them contained in himself one of the principal elements of which our universe is composed,—earth, water, sky, sun, moon, and the stars which moved around the terrestrial mountain. The succession of natural phenomena with them was not the result of unalterable laws; it was due entirely to a series of voluntary acts, accomplished by beings of different grades of intelligence and power. Every part of the great whole is represented by a god, a god who is a man, a Chaldæan, who, although of a finer and more lasting nature than other Chaldæans, possesses nevertheless the same instincts and is swayed by the same passions. He is, as a rule, wanting in that somewhat lithe grace of form, and in that rather easy-going good-nature, which were the primary characteristics of the Egyptian gods: the Chaldæan divinity has the broad shoulders, the thick-set figure and projecting muscles of the people over whom he rules; he has their hasty and violent temperament, their coarse sensuality, their cruel and warlike propensities, their boldness in conceiving undertakings, and their obstinate tenacity in carrying them out. Their goddesses are modelled on the tyra of the Chaldæn women, or, more properly speaking, on that of their queens. The majority of them do not quit the harem, and have no other ambition than to become speedily the mother of a numerous offspring. Those who openly reject the rigid constraints of such a life, and who seek to share the rank of the gods, seem to lose all self-restraint when they put off the veil: like Ishtar, they exchange a life of severe chastity for the lowest debauchery, and they subject their followers to the same irregular life which they themselves have led. “Every woman born in the country must enter once during her lifetime the enclosure of the temple of Aphrodite, must there sit down and unite herself to a stranger. Many who are wealthy are too proud to mix with the rest, and repair thither in closed chariots, followed by a considerable train of slaves. The greater number seat themselves on the sacred pavement, with a cord twisted about their heads,—and there is always a great crowd there, coming and going; the women being divided by ropes into long lanes, down which strangers pass to make their choice. A woman who has once taken her place here cannot return home until a stranger has thrown into her lap a silver coin, and has led her away with him beyond the limits of the sacred enclosure. As he throws the money he pronounces these words: ‘May the goddess Mylitta make thee happy! ‘—Now, among the Assyrians, Aphrodite is called Mylitta. The silver coin may be of any value, but none may refuse it, that is forbidden by the law, for, once thrown, it is sacred. The woman follows the first man who throws her the money, and repels no one. When once she has accompanied him, and has thus satisfied the goddess, she returns to her home, and from thenceforth, however large the sum offered to her, she will yield to no one. The women who are tall or beautiful soon return to their homes, but those who are ugly remain a long time before they are able to comply with the law; some of them are obliged to wait three or four years within the enclosure.” * This custom still existed in the Vth century before our era, and the Greeks who visited Babylon about that time found it still in full force. …

“Animals never became objects of habitual worship as in Egypt: some of them, however, such as the bull and lion, were closely allied to the gods, and birds unconsciously betrayed by their flight or cries the secrets of futurity.* In addition to all these, each family possessed its household gods, to whom its members recited prayers and poured libations night and morning, and whose statues set up over the domestic hearth defended it from the snares of the evil ones.** The State religion, which all the inhabitants of the same city, from the king down to the lowest slave, were solemnly bound to observe, really represented to the Chaldæans but a tithe of their religious life: it included some dozen gods, no doubt the most important, but it more or less left out of account all the others, whose anger, if aroused by neglect, might become dangerous. The private devotion of individuals supplemented the State religion by furnishing worshippers for most of the neglected divinities, and thus compensated for what was lacking in the official public worship of the community. …

“The sky-gods and the earth-gods had been more numerous at the outset than they were subsequently. We recognize as such Anu, the immovable firmament, and the ancient Bel, the lord of men and of the soil on which they live, and into whose bosom they return after, death; but there were others, who in historic times had partially or entirely lost their primitive character,—such as Nergal, Ninib, Dumuzi; or, among the goddesses, Damkina, Esharra, and even Ishtar herself, who, at the beginning of their existence, had represented only the earth, or one of its most striking aspects. For instance, Nergal and Ninib were the patrons of agriculture and protectors of the soil, Dumuzi was the ground in spring whose garment withered at the first approach of summer, Damkina was the leafy mould in union with fertilizing moisture, Esharra was the field whence sprang the crops, Ishtar was the clod which again grew green after the heat of the dog days and the winter frosts. All these beings had been forced to submit in a greater or less degree to the fate which among most primitive races awaits those older earth-gods, whose manifestations are usually too vague and shadowy to admit of their being grasped or represented by any precise imagery without limiting and curtailing their spheres. New deities had arisen of a more definite and tangible kind, and hence more easily understood, and having a real or supposed province which could be more easily realized, such as the sun, the moon, and the fixed or wandering stars. The moon is the measure of time; it determines the months, leads the course of the years, and the entire life of mankind and of great cities depends upon the regularity of its movements: the Chaldæans, therefore, made it, or rather the spirit which animated it, the father and king of the gods; but its suzerainty was everywhere a conventional rather than an actual superiority, and the sun, which in theory was its vassal, attracted more worshippers than the pale and frigid luminary. Some adored the sun under its ordinary title of Shamash, corresponding to the Egyptian Râ; others designated it as Merodach, Ninib, Nergal, Dumuzi, not to mention other less usual appellations. Nergal in the beginning had nothing in common with Ninib, and Merodach differed alike from Shamash, Ninib, Nergal, and Dumuzi; but the same movement which instigated the fusion of so many Egyptian divinities of diverse nature, led the gods of the Chaldæans to divest themselves little by little of their individuality and to lose themselves in the sun. Each one at first became a complete sun, and united in himself all the innate virtues of the sun—its brilliancy and its dominion over the world, its gentle and beneficent heat, its fertilizing warmth, its goodness and justice, its emblematic character of truth and peace; besides the incontestable vices which darken certain phases of its being—the fierceness of its rays at midday and in summer, the inexorable strength of its will, its combative temperament, its irresistible harshness and cruelty. By degrees they lost this uniform character, and distributed the various attributes among themselves. If Shamash continued to be the sun in general, Ninib restricted himself, after the example of the Egyptian Harmakhis, to being merely the rising and setting sun, the sun on the two horizons. Nergal became the feverish and destructive summer sun.* Merodach was transformed into the youthful sun of spring and early morning;** Dumuzi, like Merodach, became the sun before the summer. Their moral qualities naturally were affected by the process of restriction which had been applied to their physical being, and the external aspect now assigned to each in accordance with their several functions differed considerably from that formerly attributed to the unique type from which they had sprung. Ninib was represented as valiant, bold, and combative; he was a soldier who dreamed but of battle and great feats of arms. Nergal united a crafty fierceness to his bravery: not content with being lord of battles, he became the pestilence which breaks out unexpectedly in a country, the death which comes like a thief, and carries off his prey before there is time to take up arms against him. Merodach united wisdom with courage and strength: he attacked the wicked, protected the good, and used his power in the cause of order and justice. A very ancient legend, which was subsequently fully developed among the Canaanites, related the story of the unhappy passion of Ishtar for Dumuzi. The goddess broke out yearly into a fresh frenzy, but the tragic death of the hero finally moderated the ardour of her devotion. She wept distractedly for him, went to beg the lords of the infernal regions for his return, and brought him back triumphantly to the earth: every year there was a repetition of the same passionate infatuation, suddenly interrupted by the same mourning. The earth was united to the young sun with every recurring spring, and under the influence of his caresses became covered with verdure; then followed autumn and winter, and the sun, grown old, sank into the tomb, from whence his mistress had to call him up, in order to plunge afresh with him by a common impulse into the joys and sorrows of another year.” G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3

Constellations and Planets

The Chaldæans, like the Egyptians, fancied they discerned in the points of light which illuminate the nightly sky, the outline of a great number of various figures—men, animals, monsters, real and imaginary objects, a lance, a bow, a fish, a scorpion, ears of wheat, a bull, and a lion. The majority of these were spread out above their heads on the surface of the celestial vault; but twelve of these figures, distinguishable by their brilliancy, were arranged along the celestial horizon in the pathway of the sun, and watched over his daily course along the walls of the world. These divided this part of the sky into as many domains or “houses,” in which they exercised absolute authority, and across which the god could not go without having previously obtained their consent, or having brought them into subjection beforehand. This arrangement is a reminiscence of the wars by which Bel-Merodach, the divine bull, the god of Babylon, had succeeded in bringing order out of chaos: he had not only killed Tiâmat, but he had overthrown and subjugated the monsters which led the armies of darkness. He meets afresh, every year and every day, on the confines of heaven and earth, the scorpion-men of his ancient enemy, the fish with heads of men or goats, and many more. The twelve constellations were combined into a zodiac, whose twelve signs, transmitted to the Greeks and modified by them, may still be read on our astronomical charts. The constellations, immovable, or actuated by a slow motion, in longitude only, contain the problems of the future, but they are not sufficient of themselves alone to furnish man with the solution of these problems. The heavenly bodies capable of explaining them, the real interpreters of destiny, were at first the two divinities who rule the empires of night and day—the moon and the sun; afterwards there took part in this work of explanation the five planets which we call Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, Mars, and Mercury, or rather the five gods who actuate them, and who have controlled their course from the moment of creation—Merodach, Ishtar, Ninib, Nergal, and Nebo. The planets seemed to traverse the heavens in every direction, to cross their own and each other’s paths, and to approach the fixed stars or recede from them; and the species of rhythmical dance in which they are carried unceasingly across the celestial spaces revealed to men, if they examined it attentively, the irresistible march of their own destinies, as surely as if they had made themselves master of the fatal tablets of Shamash, and could spell them out line by line.

The Chaldæns were disposed to regard the planets as perverse sheep who had escaped from the fold of the stars to wander wilfully in search of pasture.* At first they were considered to be so many sovereign deities, without other function than that of running through the heavens and furnishing there predictions of the future; afterwards two of them descended to the earth, and received upon it the homage of men* —Ishtar from the inhabitants of the city of Dilbat, and Nebo* from those of Borsippa. Nebo assumed the rôle of a soothsayer and a prophet. He knew and foresaw everything, and was ready to give his advice upon any subject: he was the inventor of the method of making clay tablets, and of writing upon them. Ishtar was a combination of contradictory characteristics.**** G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3

Image Credit: Wikipedia

[The Red Sea is the same as the ancient Erythraean Sea, which was a geographical designation for the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa. The name “Erythraean Sea” was used in ancient Greek geography to refer to the Indian Ocean region, and was often extended to include the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and Indian Ocean as a single maritime area. Google ai]

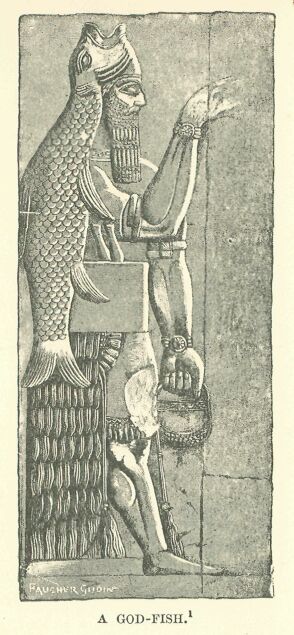

Oannes

“But, in the first year, [after the creation of the Chaldeab world,bappeared a monster endowed with human reason named Oannes, who rose from out of the Erythraean sea, [The Red Sea] at the point where it borders Babylonia. He had the whole body of a fish, but above his fish’s head he had another head which was that of a man, and human feet emerged from beneath his fish’s tail; he had a human voice, and his image is preserved to this day. He passed the day in the midst of men without taking any food; he taught them the use of letters, sciences and arts of all kinds, the rules for the founding of cities, and the construction of temples, the principles of law and of surveying; he showed them how to sow and reap; he gave them all that contributes to the comforts of life. Since that time nothing excellent has been invented. At sunset this monster Oannes plunged back into the sea, and remained all night beneath the waves, for he was amphibious. He wrote a book on the origin of things and of civilization, which he gave to men.” These are a few of the fables which were current among the races of the Lower Euphrates with regard to the first beginnings of the universe. That they possessed many other legends of which we now know nothing is certain, but either they have perished for ever, or the works in which they were recorded still await discovery, it may be under the ruins of a palace or in the cupboards of some museum.” G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3.

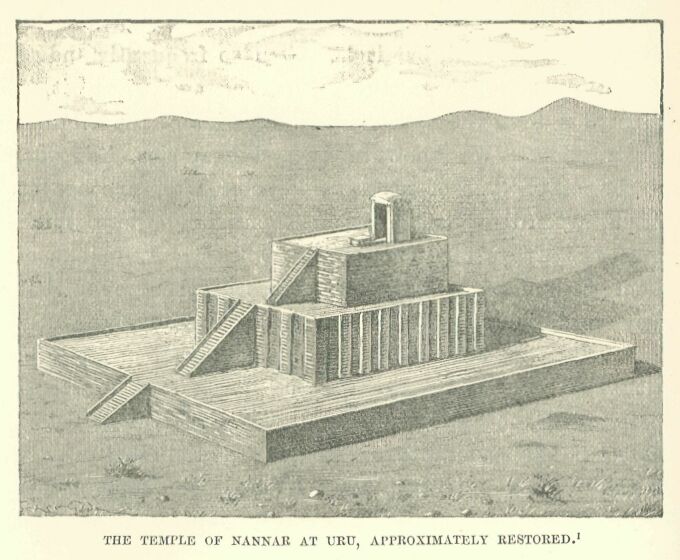

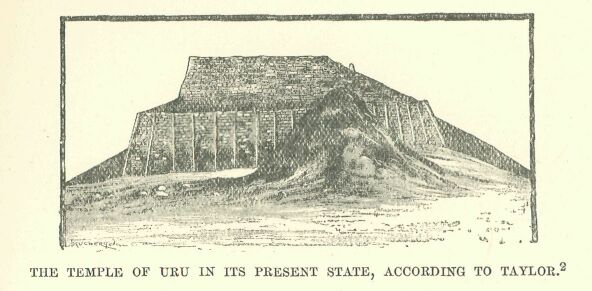

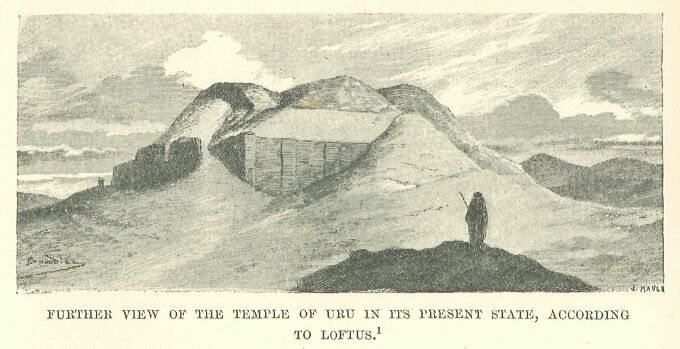

Because stone was too difficult for the Chaldeans to transport, they built their temples out of locally made bricks,I

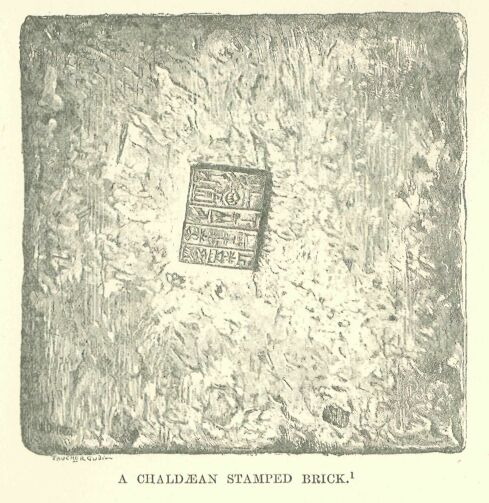

“In the estimation of the Chaldæan architects, stone was a material of secondary consideration: as it was necessary to bring it from a great distance and at considerable expense, they used it very sparingly, and then merely for lintels, uprights, thresholds, for hinges on which to hang their doors, for dressings in some of their state apartments, in cornices or sculptured friezes on the external walls of their buildings; and even then its employment suggested rather that of a band of embroidery carefully disposed on some garment to relieve the plainness of the material. Crude brick, burnt brick, enamelled brick, but always and everywhere brick was the principal element in their construction. The soil of the marshes or of the plains, separated from the pebbles and foreign substances which it contained, mixed with grass or chopped straw, moistened with water, and assiduously trodden underfoot, furnished the ancient builders with materials of incredible tenacity. This was moulded into thin square bricks, eight inches to a foot across, and three to four inches thick, but rarely larger: they were stamped on the flat side, by means of an incised wooden block, with the name of the reigning sovereign, and were then dried in the sun.* A layer of fine mortar or of bitumen was sometimes spread between the courses, or handfuls of reeds would be strewn at intervals between the brickwork to increase the cohesion: more frequently the crude bricks were piled one upon another, and their natural softness and moisture brought about their rapid agglutination.** As the building proceeded, the weight of the courses served to increase still further the adherence of the layers: the walls soon became consolidated into a compact mass, in which the horizontal strata were distinguishable only by the varied tints of the clay used to make the different relays of bricks.” G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3.

“Monuments constructed of such …material required constant attention and frequent repairs, to keep them in good condition: after a few years of neglect they became quite disfigured, the houses suffered a partial dissolution in every storm, the streets were covered with a coating of fine mud, and the general outline of the buildings and habitations grew blurred and defaced. Whilst in Egypt the main features of the towns are still traceable above ground, and are so well preserved in places that, while excavating them, we are carried away from the present into the world of the past, the Chaldæan cities, on the contrary, are so overthrown and seem to have returned so thoroughly to the dust from which their founders raised them, that the most patient research and the most enlightened imagination can only imperfectly reconstitute their arrangement.” G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria. vol. 3.

.

[Keep in mind that this book was published in 19

Ashur

Ashur was the national god of the Assyrians.[78] It has been proposed that originally he was the deification of the city of Assur,[79] or perhaps the hill atop which it was built.[80] He initially lacked any connections to other deities, having no parents, spouse or children.[81] The only goddess related to him, though in an unclear way, was Šerua.[81] Later he was syncretized with Enlil,[82][72] and as a result Ninlil was sometimes regarded as his wife, and Ninurta and Zababa as his sons.[81] Sargon II initiated the trend of writing his name with the same signs as that of Anshar, a primordial being regarded as Anu’s father in the theology of Enuma Elish.[72] He may have originally been a local deity associated with the city of Assur,[78] but, with the growth of the Assyrian Empire,[78] his cult was introduced to southern Mesopotamia.[83] In Assyrian texts Bel was a title of Ashur, rather than Marduk.[84]

Nabu

“Nabu was the Mesopotamian god of scribes and writing.[85] His wife was the goddess Tashmetu[85] and he may have been associated with the planet Mercury,[85] though the evidence has been described as “circumstantial” by Francesco Pomponio.[87] He later became associated with wisdom and agriculture.[85] In the Old Babylonian and early Kassite periods his cult was only popular in central Mesopotamia (Babylon, Sippar, Kish, Dilbat, Lagaba), had a limited extent in peripheral areas (Susa in Elam, Mari in Syria) and there is little to no evidence of it from cities such as Ur and Nippur, in sharp contrast with later evidence.[88] In the first millennium BCE he became one of the most prominent gods of Babylonia.[88] In Assyria his prominence grew in the eighth and seventh centuries BCE.[86] In Kalhu and Nineveh he eventually became more common in personal names than the Assyrian head god Ashur.[86] He also replaced Ninurta as the main god of Kalhu.[86] In the Neo-Babylonian periods some inscriptions of kings such as Nebuchadnezzar II indicate that Nabu could take precedence even over the supreme Babylonian god Marduk.[86] His cult also spread beyond Mesopotamia, to cities such as Palmyra, Hierapolis, Edessa or Dura Europos,[89] and to Egypt, as far as Elephantine, where in sources from the late first millennium BCE he is the most frequently attested foreign god next to Yahweh.[89]

Ninhursag

“Ninhursag (“Mistress of the mountain ranges”[109]), also known as Damgalnuna, Ninmah, Nintur[110] and Aruru,[111] was the Mesopotamian mother goddess. Her primary functions were related to birth (but generally not to nursing and raising children, with the exception of sources from early Lagash) and creation.[112] Descriptions of her as “mother” weren’t always referring to motherhood in the literal sense or to parentage of other deities, but sometimes instead represented her esteem and authority as a senior deity, similar to references to major male deities such as Enlil or Anu as “fathers.”[113] Certain mortal rulers claimed her as their mother,[108] a phenomenon recorded as early as during the reign of Mesilim of Kish (c. 2700 BCE).[114] She was the wife of Enki,[108] though in some locations (including Nippur) her husband was Šulpae instead.[115] Initially no city had Ninhursag as its tutelary goddess.[116] Later her main temple was the E-Mah in Adab,[108] originally dedicated to a minor male deity, Ašgi.[117] She was also associated with the city of Kesh,[108] where she replaced the local goddess Nintur,[111] and she was sometimes referred to as the “Bēlet-ilī of Kesh” or “she of Kesh”.[108] It is possible her emblem was a symbol similar to later Greek letter omega.[118]

More Coming

.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.