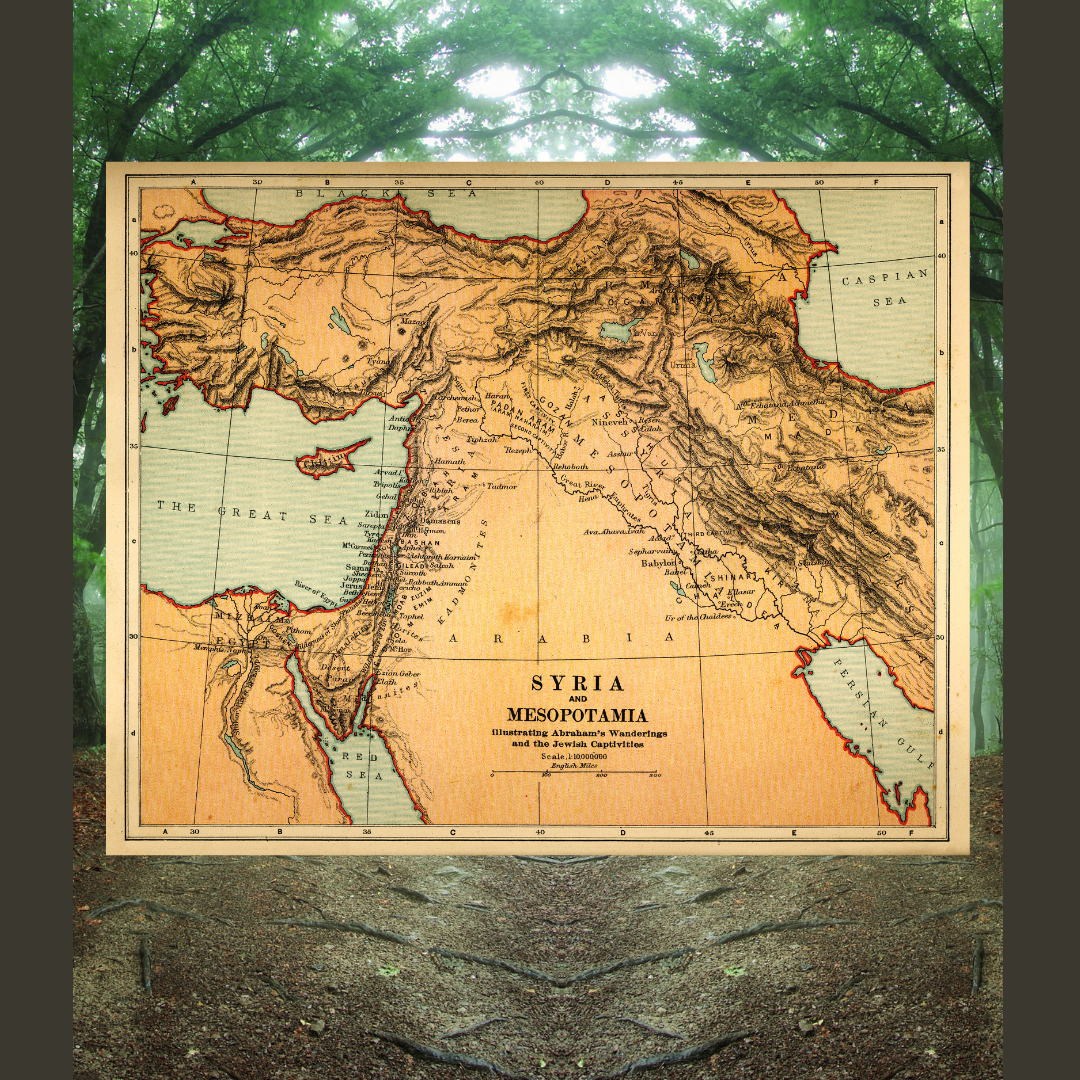

The area between the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers is called Mesopotamia. Most Biblical scholars believe that this is the region where the Garden of Eden was–the land of Adam and Eve. But most scholars of Chaldean Paganism also believe that this area is where the Chaldean Pagan Story of Creation began.

“Like the Egyptian civilization, it had had its birth between the sea and the dry land on a low, marshy, alluvial soil, flooded annually by the rivers which traverse it, devastated at long intervals by tidal waves of extraordinary violence. The Euphrates and the Tigris cannot be regarded as mysterious streams like the Nile, whose source so long defied exploration that people were tempted to place it beyond the regions inhabited by man. The former rise in Armenia, on the slopes of the Niphates, one of the chains of mountains which lie between the Black Sea and Mesopotamia, and the only range which at certain points reaches the line of eternal snow. At first they flow parallel to one another, the Euphrates from east to west as far as Malatiyeh, the Tigris from the west towards the east in the direction of Assyria. Beyond Malatiyeh, the Euphrates bends abruptly to the south-west, and makes its way across the Taurus as though desirous of reaching the Mediterranean by the shortest route, but it soon alters its intention, and makes for the south-east in search of the Persian Gulf. The Tigris runs in an oblique direction towards the south from the point where the mountains open out, and gradually approaches the Euphrates. Near Bagdad the two rivers are only a few leagues apart. However, they do not yet blend their waters; after proceeding side by side for some twenty or thirty miles, they again separate and only finally; unite at a point some eighty leagues lower down. At the beginning of our geological period their course was not such a long one. The sea then penetrated as far as lat. 33°, and was only arrested by the last undulations of the great plateau of secondary formation, which descend from the mountain group of Armenia: the two rivers entered the sea at a distance of about twenty leagues apart, falling into a gulf bounded on the east by the last spurs of the mountains of Iran, on the west by the sandy heights which border the margin of the Arabian Desert.* They filled up this gulf with their alluvial deposit, aided by the Adhem, the Diyâleh, the Kerkha, the Karun, and other rivers, which at the end of long independent courses became tributaries of the Tigris. The present beds of the two rivers, connected by numerous canals, at length meet near the village of Kornah and form one single river, the Shatt-el-Arab, which carries their waters to the sea. The mud with which they are charged is deposited when it reaches their mouth, and accumulates rapidly; it is said that the coast advances about a mile every seventy years.** In its upper reaches the Euphrates collects a number of small affluents, the most important of which, the Kara-Su, has often been confounded with it. Near the middle of its course, the Sadjur on the right bank carries into it the waters of the Taurus and the Amanus, on the left bank the Balikh and the Khabur contribute those of the Karadja-Dagh; from the mouth of the Khabur to the sea the Euphrates receives no further affluent. The Tigris is fed on the left by the Bitlis-Khai, the two Zabs, the Adhem, and the Diyâleh. The Euphrates is navigable from Sumeisat, the Tigris from Mossul, both of them almost as soon as they leave the mountains. They are subject to annual floods, which occur when the winter snow melts on the higher ranges of Armenia. The Tigris, which rises from the southern slope of the Niphates and has the more direct course, is the first to overflow its banks, which it does at the beginning of March, and reaches its greatest height about the 10th or 12th of May. The Euphrates rises in the middle of March, and does not attain its highest level till the close of May. From June onwards it falls with increasing rapidity; by September all the water which has not been absorbed by the soil has returned to the river-bed. The inundation does not possess the same importance for the regions covered by it, that the rise of the Nile does for Egypt. In fact, it does more harm than good, and the river-side population have always worked hard to protect themselves from it and to keep it away from their lands rather than facilitate its access to them; they regard it as a sort of necessary evil to which they resign themselves, while trying to minimize its effects.***

‘The traveller Olivier noticed this, and writes as follows: “The land there is rather less fertile [than in Egypt], because it does not receive the alluvial deposits of the rivers with the same regularity as that of the Delta. It is necessary to irrigate it in order to render it productive, and to protect it sedulously from the inundations which are too destructive in their action and too irregular.”

The First People Were Semites

“The first races to colonize this country of rivers, or at any rate the first of which we can find traces, seem to have belonged to three different types. The most important were the Semites, who spoke a dialect akin to Aramaic, Hebrew, and Phoenician. It was for a long time supposed that they came down from the north, and traces of their occupation have been pointed out in Armenia in the vicinity of Ararat, or halfway down the course of the Tigris, at the foot of the Gordysean mountains. It has recently been suggested that we ought rather to seek for their place of origin in Southern Arabia, and this view is gaining ground among the learned. Side by side with these Semites, the monuments give evidence of a race of ill-defined character, which some have sought, without much success, to connect with the tribes of the Urall or Altaï; these people are for the present provisionally called Sumerians.* They came, it would appear, from some northern country; they brought with them from their original home a curious system of writing, which, modified, transformed, and adopted by ten different nations, has preserved for us all that we know in regard to the majority of the empires which rose and fell in Western Asia before the Persian conquest. Semite or Sumerian, it is still doubtful which preceded the other at the mouths of the Euphrates. The Sumerians, who were for a time all-powerful in the centuries before the dawn of history, had already mingled closely with the Semites when we first hear of them. Their language gave way to the Semitic, and tended gradually to become a language of ceremony and ritual, which was at last learnt less for everyday use, than for the drawing up of certain royal inscriptions, or for the interpretation of very ancient texts of a legal or sacred character. Their religion became assimilated to the religion, and their gods identified with the gods, of the Semites. The process of fusion commenced at such an early date, that nothing has really come down to us from the time when the two races were strangers to each other. We are, therefore, unable to say with certainty how much each borrowed from the other, what each gave, or relinquished of its individual instincts and customs. We must take and judge them as they come before us, as forming one single nation, imbued with the same ideas, influenced in all their acts by the same civilization, and possessed of such strongly marked characteristics that only in the last days of their existence do we find any appreciable change. In the course of the ages they had to submit to the invasions and domination of some dozen different races, of whom some—Assyrians and Chaldæans—were descended from a Semitic stock, while the others—Elamites, Cossaaans, Persians, Macedonians, and Parthians—either were not connected with them by any tie of blood, or traced their origin in some distant manner to the Sumerian branch. They got quickly rid of a portion of these superfluous elements, and absorbed or assimilated the rest; like the Egyptians, they seem to have been one of those races which, once established, were incapable of ever undergoing modification, and remained unchanged from one end of their existence to the other.a

Description of the Area

“Their country must have presented at the beginning very much the same aspect of disorder and neglect which it offers to modern eyes. It was a flat interminable moorland stretching away to the horizon, there to begin again seemingly more limitless than ever, with, no rise or fall in the ground to break the dull monotony; clumps of palm trees and slender mimosas, intersected by lines of water gleaming in the distance, then long patches of wormwood and mallow, endless vistas of burnt-up plain, more palms and more mimosas, make up the picture of the land, whose uniform soil consists of rich, stiff, heavy clay, split up by the heat of the sun into a network of deep narrow fissures, from which the shrubs and wild herbs shoot forth each year in spring-time. By an almost imperceptible slope it falls gently away from north to south towards the Persian Gulf, from east to west towards the Arabian plateau. The Euphrates flows through it with unstable and changing course, between shifting banks which it shapes and re-shapes from season to season.

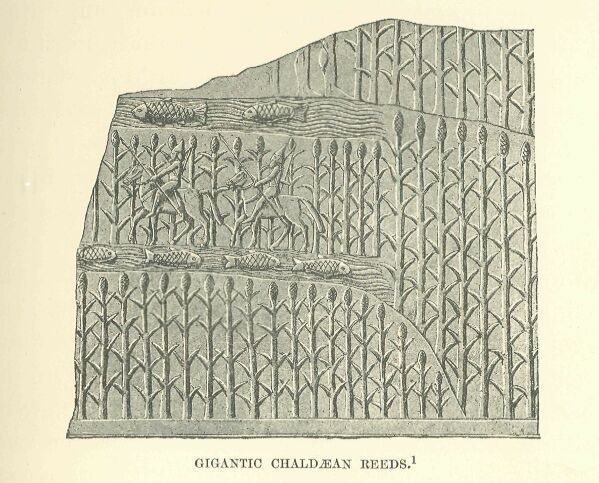

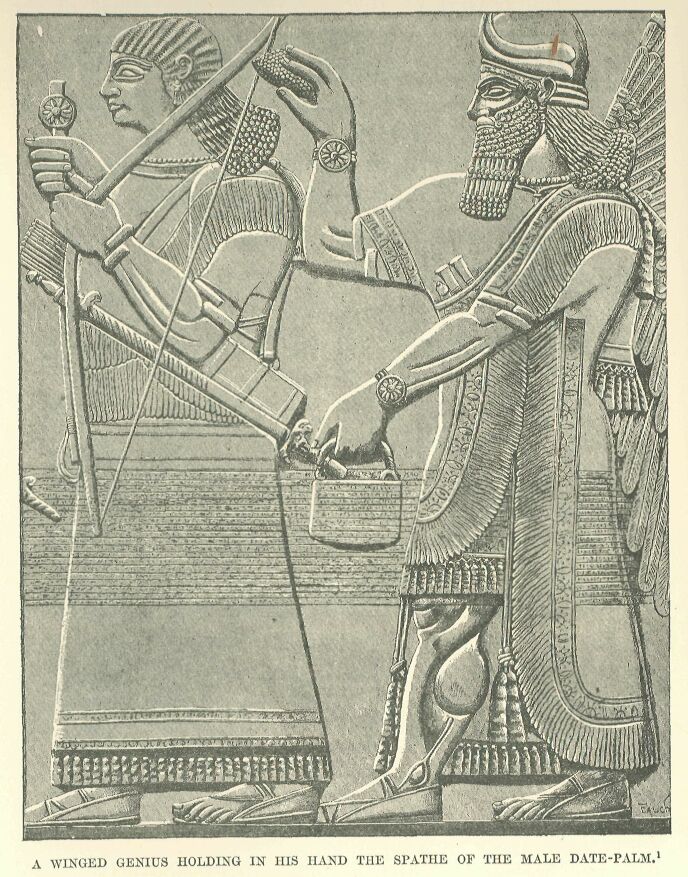

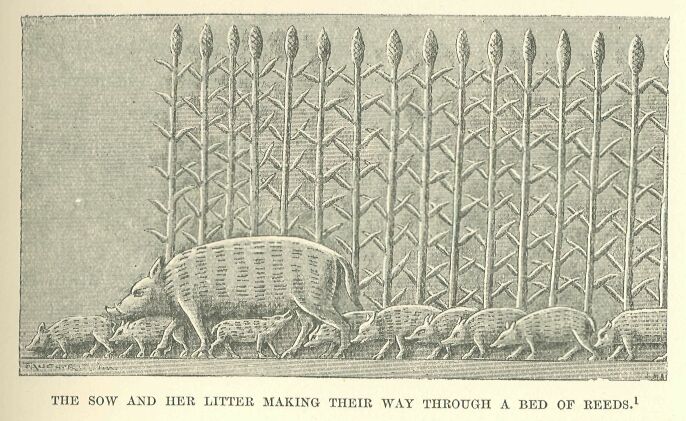

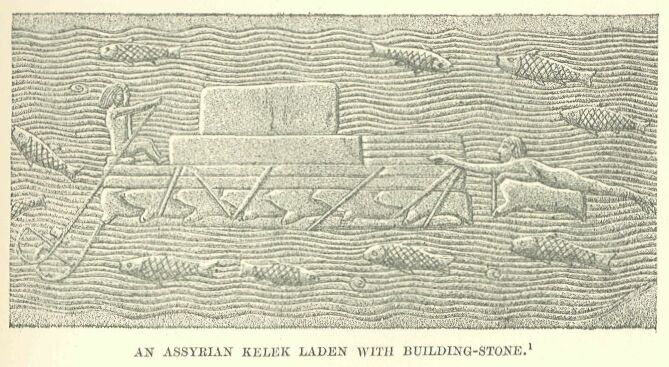

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from an Assyrian bas-relief of the

palace of Nimrûd.

[I am reminded of the story of the hiding of Moses in the bullrushes. There is a similar story about Mesopotamia:

“Moses’ story begins when Pharaoh feels threatened by the growing Hebrew population in Egypt and commands that all Hebrew male infants be killed (Exod 1:16–22 ). Moses’ mother hides her newborn son for three months and then devises a risky but calculated plan: She sets him adrift on the Nile in a small basket made of bulrushes, waterproofed with bitumen and pitch (2:1–3). Moses’ older sister, Miriam, watches as the basket floats to where the daughter of Pharaoh bathes. God uses these circumstances to bring Moses under the protection of Egypt’s ruler (2:4–10).

). Moses’ mother hides her newborn son for three months and then devises a risky but calculated plan: She sets him adrift on the Nile in a small basket made of bulrushes, waterproofed with bitumen and pitch (2:1–3). Moses’ older sister, Miriam, watches as the basket floats to where the daughter of Pharaoh bathes. God uses these circumstances to bring Moses under the protection of Egypt’s ruler (2:4–10).

“Ancient literature outside the Bible attests to several stories in which a child, perceived as a threat by an enemy, is abandoned and later spared by divine intervention or otherworldly circumstance. Roughly 30 stories like this survive from the literature of ancient Mesopotamia, Canaan, Greece, Egypt, Rome and India.

“The Mesopotamian work known as the Sargon Birth Legend offers the most striking parallels to the biblical story. It relates the birth story of Sargon the Great, an Akkadian emperor who ruled a number of Sumerian city-states around 2000 bc, centuries before the time of Moses. The infant boy is born into great peril: His mother is a high priestess, and he is illegitimate. Consequently, his mother sets him adrift on a river in a reed basket. The boy is rescued and raised by a gardener named Akki in the town of Kish. He becomes a humble gardener in Akki’s service until the goddess Ishtar takes an interest in him, setting him on the path to kingship.” Logos]

“The slightest impulse of its current encroaches on them, breaks through them, and makes openings for streamlets, the majority of which are clogged up and obliterated by the washing away of their margins, almost as rapidly as they are formed. Others grow wider and longer, and, sending out branches, are transformed into permanent canals or regular rivers, navigable at certain seasons. They meet on the left bank detached offshoots of the Tigris, and after wandering capriciously in the space between the two rivers, at last rejoin their parent stream: such are the Shatt-el-Haî and the Shatt-en-Nil. The overflowing waters on the right bank, owing to the fall of the land, run towards the low limestone hills which shut in the basin of the Euphrates in the direction of the desert; they are arrested at the foot of these hills, and are diverted on to the low-lying ground, where they lose themselves in the morasses, or hollow out a series of lakes along its borders, the largest of which, Bahr-î-Nedjîf, is shut in on three sides by steep cliffs, and rises or falls periodically with the floods. A broad canal, which takes its origin in the direction of Hit at the beginning of the alluvial plain, bears with it the overflow, and, skirting the lowest terraces of the Arabian chain, runs almost parallel to the Euphrates. In proportion as the canal proceeds southward the ground sinks still lower, and becomes saturated with the overflowing waters, until, the banks gradually disappearing, the whole neighbourhood is converted into a morass. The Euphrates and its branches do not at all times succeed in reaching the sea: they are lost for the most part in vast lagoons to which the tide comes up, and in its ebb bears their waters away with it. Reeds grow there luxuriantly in enormous beds, and reach sometimes a height of from thirteen to sixteen feet; banks of black and putrid mud emerge amidst the green growth, and give off deadly emanations. Winter is scarcely felt here: snow is unknown, hoar-frost is rarely seen, but sometimes in the morning a thin film of ice covers the marshes, to disappear under the first rays of the sun.*

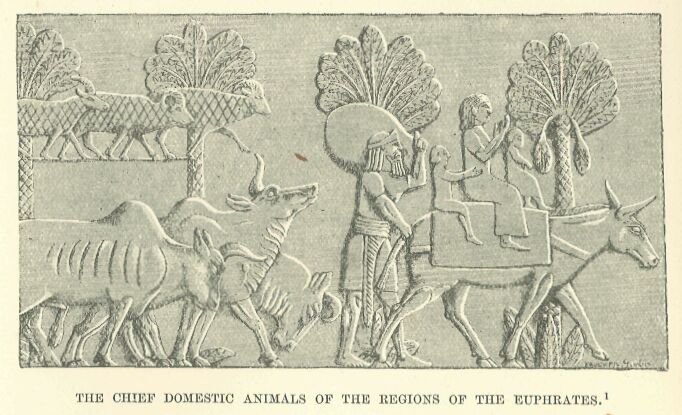

“Notwithstanding these drawbacks, the country was not lacking in resources. The soil was almost as fertile as the loam of Egypt, and, like the latter, rewarded a hundredfold the labour of the inhabitants.* Among the wild herbage which spreads over the country in the spring, and clothes it for a brief season with flowers, it was found that some plants, with a little culture, could be rendered useful to men and beasts. There were ten or twelve different species of pulse to choose from—beans, ‘lentils, chick-peas, vetches, kidney beans, onions, cucumbers, egg-plants, “gombo,” and pumpkins. From the seed of the sesame an oil was expressed which served for food, while the castor-oil plant furnished that required for lighting. The safflower and henna supplied the women with dyes for the stuffs which they manufactured from hemp and flax. Aquatic plants were more numerous than on the banks of the Nile, but they did not occupy such an important place among food-stuffs. The “lily bread” of the Pharaohs would have seemed meagre fare to people accustomed from early times to wheaten bread. Wheat and barley are considered to be indigenous on the plains of the Euphrates; it was supposed to be here that they were first cultivated in Western Asia, and that they spread from hence to Syria, Egypt, and the whole of Europe.** “The soil there is so favourable to the growth of cereals, that it yields usually two hundredfold, and in places of exceptional fertility three hundredfold. The leaves of the wheat and barley have a width of four digits. As for the millet and sesame, which in altitude are as great as trees, I will not state their height, although I know it from experience, being convinced that those who have not lived in Babylonia would regard my statement with incredulity.” Herodotus in his enthusiasm exaggerated the matter, or perhaps, as a general rule, he selected as examples the exceptional instances which had been mentioned to him: at present wheat and barley give a yield to the husbandman of some thirty or forty fold.

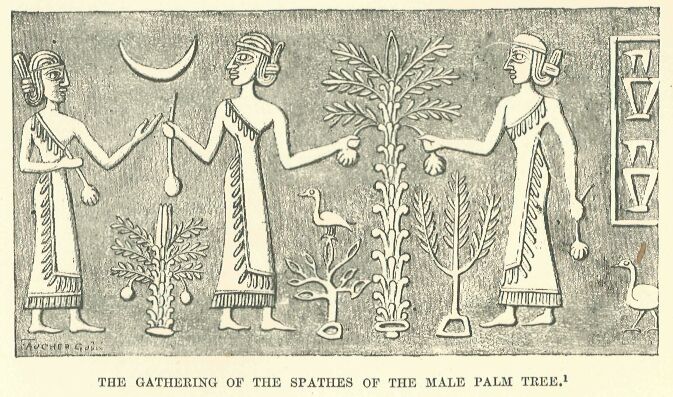

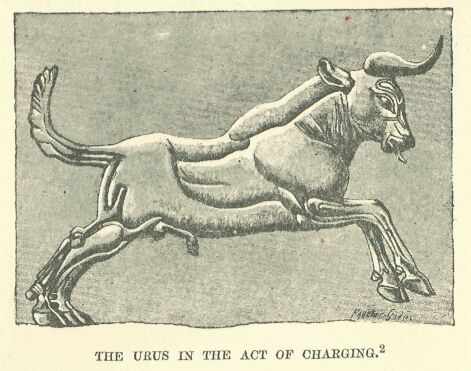

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a cylinder in the Museum at the

Hague. The original measures almost an inch in height.

“The date palm meets all the other needs of the population; they make from it a kind of bread, wine, vinegar, honey, cakes, and numerous kinds of stuffs; the smiths use the stones of its fruit for charcoal; these same stones, broken and macerated, are given as a fattening food to cattle and sheep.” Such a useful tree was tended with a loving care, the vicissitudes in its growth were observed, and its reproduction was facilitated by the process of shaking the flowers of the male palm over those of the female: the gods themselves had taught this artifice to men, and they were frequently represented with a bunch of flowers in their right hand, in the attitude assumed by a peasant in fertilizing a palm tree. Fruit trees were everywhere mingled with ornamental trees—the fig, apple, almond, walnut, apricot, pistachio, vine, with the plane tree, cypress, tamarisk, and acacia; in the prosperous period of the country the plain of the Euphrates was a great orchard which extended uninterruptedly from the plateau of Mesopotamia to the shores of the Persian Gulf.

“The flora would not have been so abundant if the fauna had been sufficient for the supply of a large population. A considerable proportion of the tribes on the Lower Euphrates lived for a long time on fish only.

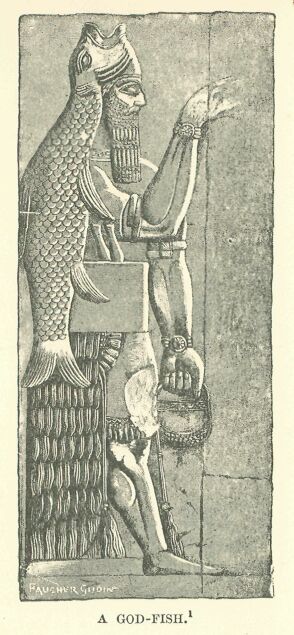

[MY THOUGHT: Perhaps this is why the great pagan god was half fish.]

They consumed them either fresh, salted, or smoked: they dried them in the sun, crushed them in a mortar, strained the pulp through linen, and worked it up into a kind of bread or into cakes. The barbel and carp attained a great size in these sluggish waters, and if the Chalæans, like the Arabs who have succeeded them in these regions, clearly preferred these fish above others, they did not despise at the same time such less delicate species as the eel, murena, silurus,

[MY THOUGHT: Perhaps this is why the great pagan god Oannes was half fish. Like the gunnard, the god was amhibian]

[Oannes

“But, in the first year, appeared a monster endowed with human reason named Oannes, who rose from out of the Erythraean sea, at the point where it borders Babylonia. He had the whole body of a fish, but above his fish’s head he had another head which was that of a man, and human feet emerged from beneath his fish’s tail; he had a human voice, and his image is preserved to this day. He passed the day in the midst of men without taking any food; he taught them the use of letters, sciences and arts of all kinds, the rules for the founding of cities, and the construction of temples, the ]principles of law and of surveying; he showed them how to sow and reap; he gave them all that contributes to the comforts of life. Since that time nothing excellent has been invented. At sunset this monster Oannes plunged back into the sea, and remained all night beneath the waves, for he was amphibious.G. Maspero. History of Egypt: Chaldea, Syria, and Assyria

and even that singular gurnard whose habits are an object of wonder to our naturalists. This fish spends its existence usually in the water, but a life in the open air has no terrors for it: it leaps out on the bank, climbs trees without much difficulty, finds a congenial habitat on the banks of mud exposed by the falling tide, and basks there in the sun, prepared to vanish in the ooze in the twinkling of an eye if some approaching bird should catch sight of it. Pelicans, herons, cranes, storks, cormorants, hundreds of varieties of seagulls, ducks, swans, wild geese, secure in the possession of an inexhaustible supply of food, sport and prosper among the reeds. The ostrich, greater bustard, the common and red-legged partridge and quail, find their habitat on the borders of the desert; while the thrush, blackbird, ortolan, pigeon, and turtle-dove abound on every side, in spite of daily onslaughts from eagles, hawks, and other birds of prey.

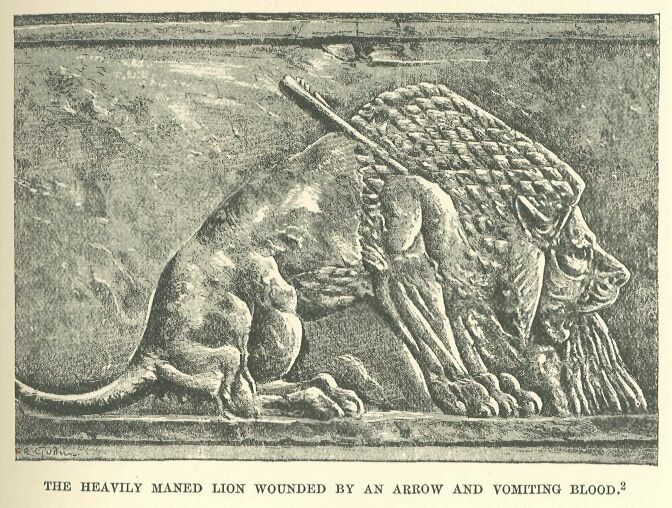

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a bas-relief from Nimrûd, in

the British Museum.

“Snakes are found here and there, but they are for the most part of innocuous species: three poisonous varieties only are known, and their bite does not produce such terrible consequences as that of the horned viper or Egyptian uraeus. There are two kinds of lion—one without mane, and the other hooded, with a heavy mass of black and tangled hair: the proper signification of the old Chaldæan name was “the great ‘dog,” and they have, indeed, a greater resemblance to large dogs than to the red lions of Africa.* They fly at the approach of man; they betake themselves in the daytime to retreats among the marshes or in the thickets which border the rivers, sallying forth at night, like the jackal, to scour the country. Driven to bay, they turn upon the assailant and fight desperately. The Chaldæan kings, like the Pharaohs, did not shrink from entering into a close conflict with them, and boasted of having rendered a service to their subjects by the destruction of many of these beasts.

“Snakes are found here and there, but they are for the most part of innocuous species: three poisonous varieties only are known, and their bite does not produce such terrible consequences as that of the horned viper or Egyptian uraeus. There are two kinds of lion—one without mane, and the other hooded, with a heavy mass of black and tangled hair: the proper signification of the old Chaldæan name was “the great ‘dog,” and they have, indeed, a greater resemblance to large dogs than to the red lions of Africa.* They fly at the approach of man; they betake themselves in the daytime to retreats among the marshes or in the thickets which border the rivers, sallying forth at night, like the jackal, to scour the country. Driven to bay, they turn upon the assailant and fight desperately. The Chaldæan kings, like the Pharaohs, did not shrink from entering into a close conflict with them, and boasted of having rendered a service to their subjects by the destruction of many of these beasts.

Cities of Ancient Mesopotamia

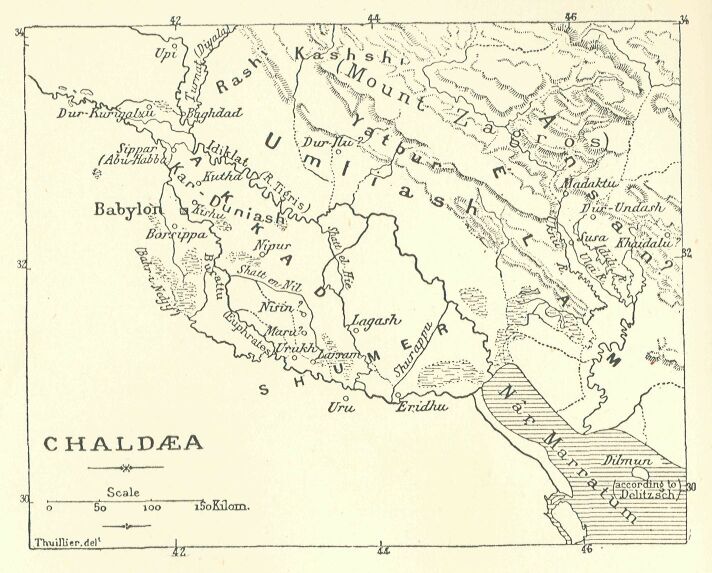

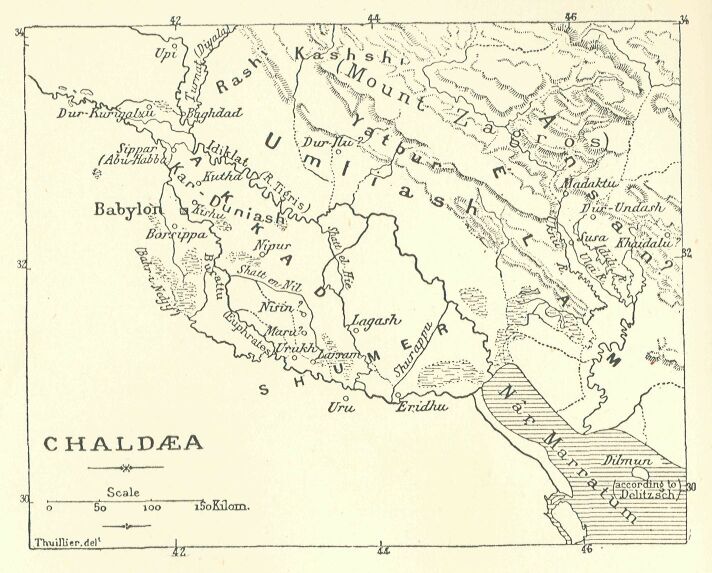

‘We know nothing of the efforts which the first inhabitants—Sumerians and Semites—had to make in order to control the waters and to bring the land under culture: the most ancient monuments exhibit them as already possessors of the soil, and in a forward state of civilization.* Their chief cities were divided into two groups: one in the south, in the neighbourhood of the sea; the other in a northern direction, in the region where the Euphrates and Tigris are separated from each other by merely a narrow strip of land.

Eridu and Ur [Uru]

The southern group consisted of seven, of which Eridu lay nearest to the coast. This town stood on the left bank of the Euphrates, at a point which is now called Abu-Shahrein. A little to the west, on the opposite bank, but at some distance from the stream, the mound of Mugheîr marks the site of Uru, the most important, if not the oldest, of the southern cities. Lagash occupied the site of the modern Telloh to the north of Eridu, not far from the Shatt-el-Haî; Nisin and Mar, Larsam and Uruk, occupied positions at short distances from each other on the marshy ground which extends between the Euphrates and the Shatt-en-Nîl. The inscriptions mention here and there other less important places, of which the ruins have not yet been discovered—Zirlab and Shurippak, places of embarkation at the mouth of the Euphrates for the passage of the Persian Gulf; and the island of Dilmun, situated some forty leagues to the south in the centre of the Salt Sea,—“Nar-Marratum.”…

Eridu

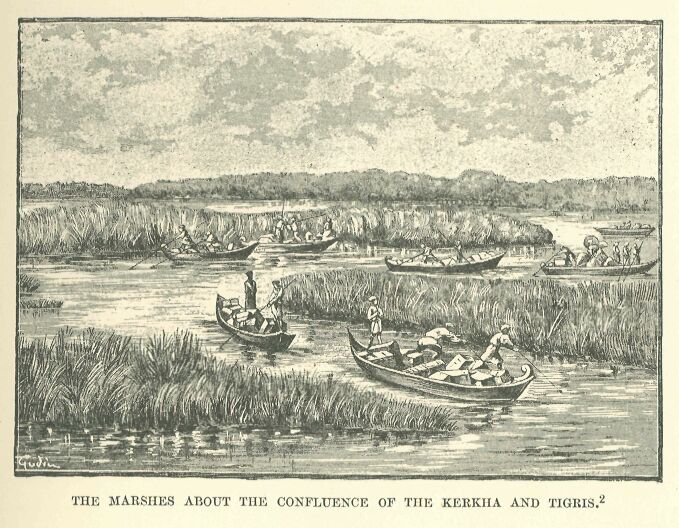

“The Shatt-el-Haî, moreover, poured its waters into the Euphrates almost opposite the city, and opened up to it commercial relations with the Upper and Middle Tigris. And this was not all; whilst some of its boatmen used its canals and rivers as highways, another section made their way to the waters of the Persian Gulf and traded with the ports on its coast. Eridu, the only city which could have barred their access to the sea, was a town given up to religion, and existed only for its temples and its gods. It was not long before it fell under the influence of its powerful neighbour, becoming the first port of call for vessels proceeding up the Euphrates.

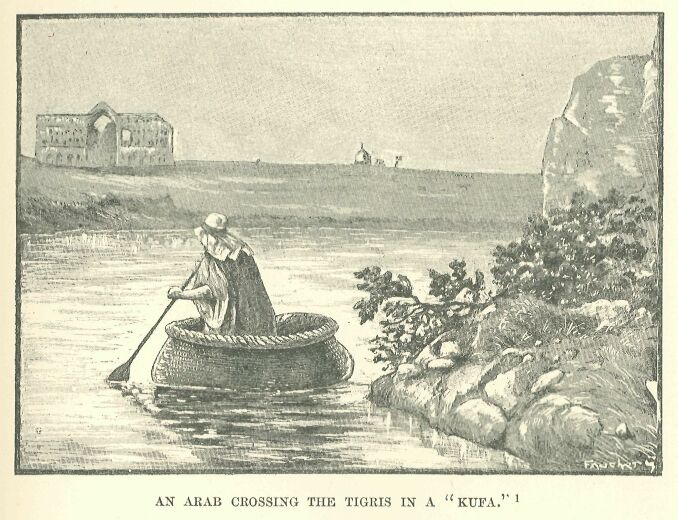

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a sketch by Chesney.

“In the time of the Greeks and Romans the Chaldaeans were accustomed to navigate the Tigris either in round flat-bottomed boats, of little draught—“kufas,” in fact—or on rafts placed upon inflated skins, exactly similar in appearance and construction to the “keleks” of our own day. These keleks were as much at home on the sea as upon the river, and they may still be found in the Persian Gulf engaged in the coasting trade. Doubtless many of these were included among the vessels of Uru mentioned in the texts, but there were also among the latter those long large rowing-boats with curved stem and stern, Egyptian in their appearance, which are to be found roughly incised on some ancient cylinders. These primitive fleets were not disposed to risk the navigation of the open sea. They preferred to proceed slowly along the shore, hugging it in all cases, except when it was necessary to reach some group of neighbouring islands; many days of navigation were thus required to make a passage which one of our smallest sail-boats would effect in a few hours, and at the end of their longest voyages they were not very distant from their point of departure. It would be a great mistake to suppose them capable of sailing round Arabia and of fetching blocks of stone by sea from the Sinaitic Peninsula; such an expedition, which would have been dangerous even for Greek or Roman Galleys, would have been simply impossible for them. If they ever crossed the Strait of Ormuzd, it was an exceptional thing, their ordinary voyages being confined within the limits of the gulf.

Ur

“The merchants of Uru were accustomed to visit regularly the island of Dilmun, the land of Mâgan, the countries of Milukhkha and Gubîn; from these places they brought cargoes of diorite for their sculptors, building-timber for their architects, perfumes and metals transported from Yemen by land, and possibly pearls from the Bahrein Islands. They encountered serious rivalry from the sailors of Dilmun and Mâgan, whose maritime tribes were then as now accustomed to scour the seas. The risk was great for those who set out on such expeditions, perhaps never to return, but the profit was considerable.

Drawn by Faucher-Gudin, from a bas-relief from “Kouyunjik”

(Layard, The Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd series, pi. 13; cf.

Place, Ninive et l’Assyrie, pl. 43, No. 1.)

“Uru, enriched by its commerce, was soon in a position to subjugate the petty neighbouring states—Uruk, Larsam, Lagash, and Nipur. Its territory formed a fairly extended sovereignty, whose lords entitled themselves kings of Shumir and Akkad, and ruled over all Southern Chaldæa for many centuries.

“Several of these kings, the Lugalkigubnidudu and the Lugalkisalsi, of whom some monuments have been preserved to us, seem to have extended their influence beyond these limits prior to the time of Sargon the Elder; and we can date the earliest of them with tolerable probability. Urbau reigned some time about 2900 B.C. He was an energetic builder, and material traces of his activity are to be found everywhere throughout the country. The temple of the Sun at Larsam, the temple of Nina in Uruk, and the temples of Inlilla and Ninlilla in Nipur were indebted to him for their origin or restoration: he decorated or repaired all structures which were not of his own erection: in Uru itself the sanctuary of the moon-god owes its foundation to him, and the fortifications of the city were his work. Dungi, his son, was an indefatigable bricklayer, like his father: he completed the sanctuary of the moon-god, and constructed buildings in Uruk, Lagash, and Kutha. There is no indication in the inscriptions of his having been engaged in any civil struggle or in war with a foreign nation; we should make a serious mistake, however, if we concluded from this silence that peace was not disturbed in his time. The tie which bound together the petty states of which Uru was composed was of the slightest. The sovereign could barely claim as his own more than the capital and the district surrounding it; the other cities recognized his authority, paid him tribute, did homage to him in religious matters, and doubtless rendered him military service also, but each one of them nevertheless maintained its particular constitution and obeyed its hereditary lords. These lords, it is true, lost their title of king, which now belonged exclusively to their suzerain, and each one had to be content in his district with the simple designation of “vicegerent;” but having once fulfilled their feudal obligations, they had absolute power over their ancient domains, and were able to transmit to their progeny the inheritance they had received from their fathers. Gudea probably, and most certainly his successors, ruled in this way over Lagash, as a fief depending on the crown of Uru. After the manner of the Egyptian barons, the vassals of the kings of Chaldaea submitted to the control of their suzerain without resenting his authority as long as they felt the curbing influence of a strong hand: but on the least sign of feebleness in their master they reasserted themselves, and endeavoured to recover their independence. A reign of any length was sure to be disturbed by rebellions sometimes difficult to repress: if we are ignorant of any such, it is owing to the fact that inscriptions hitherto discovered are found upon objects upon which an account of a battle would hardly find a fitting place, such as bricks from a temple, votive cones or cylinders of terra-cotta, amulets or private seals. We are still in ignorance as to Dungi’s successors, and the number of years during which this first dynasty was able to prolong its existence. We can but guess that its empire broke up by disintegration after a period of no long duration. Its cities for the most part became emancipated, and their rulers proclaimed themselves kings once more.

Kingdom of Amanu

We see that the kingdom of Amnanu, for instance, was established on the left bank of the Euphrates, with Uruk as its capital, and that three successive sovereigns at least—of whom Singashid seems to have been the most active—were able to hold their own there. Uru had still, however, sufficient prestige and wealth to make it the actual metropolis of the entire country. No one could become the legitimate lord of Shumir and Accad before he had been solemnly enthroned in the temple at Uru. For many centuries every ambitious kinglet in turn contended for its possession and made it his residence. The first of these, about 2500 B.C., were the lords of Nishin, Libitanunit, Gamiladar, Inedîn, Bursîn I., and Ismidâgan: afterwards, about 2400 B.C., Gungunum of Nipur made himself master of it. The descendants of Gungunum, amongst others Bursîn II., Gimilsîn, Inêsin, reigned gloriously for a few years. Their records show that they conquered not only a part of Elam, but part of Syria. They were dispossessed in their turn by a family belonging to Lârsam, whose two chief representatives, as far as we know, were Nurramman and his son Sinidinnam (about 2300 B.C.). Naturally enough, Sinidinnam was a builder or repairer of temples, but he added to such work the clearing of the Shatt-el-Haî and the excavation of a new canal giving a more direct communication between the Shatt and the Tigris, and in thus controlling the water-system of the country became worthy of being considered one of the benefactors of Chaldæa.

Babylon

The northern group comprised Nipur, the “incomparable;” Barsip, on the branch which flows parallel to the Euphrates and falls into the Bahr-î-Nedjîf; Babylon, the “gate of the god,” the “residence of life,” the only metropolis of the Euphrates region of which posterity never lost a reminiscence; Kishu, Kuta, Agade;** and lastly the two Sipparas, that of Shamash and that of Anunit. The earliest Chaldæan civilization was confined almost entirely to the two banks of the Lower Euphrates: except at its northern boundary, it did not reach the Tigris, and did not cross this river. Separated from the rest of the world—on the east by the marshes which border the river in its lower course, on the north by the badly watered and sparsely inhabited table-land of Mesopotamia, on the west by the Arabian desert—it was able to develop its civilization, as Egypt had done, in an isolated area, and to follow out its destiny in peace.

Susa

“The only point from which it might anticipate serious danger was on the east, whence the Kashshi and the Elamites, organized into military states, incessantly harassed it year after year by their attacks. The Kashshi were scarcely better than half-civilized mountain hordes, but the Elamites were advanced in civilization, and their capital, Susa, vied with the richest cities of the Euphrates, Uru and Babylon, in antiquity and magnificence.

Haran

“There was nothing serious to fear from the Guti, on the branch of the Tigris to the north-east, or from the Shuti to the north of these; they were merely marauding tribes, and, however troublesome they might be to their neighbours in their devastating incursions, they could not compromise the existence of the country, or bring it into subjection. It would appear that the Chaldseans had already begun to encroach upon these tribes and to establish colonies among them—El-Ashshur on the banks of the Tigris, Harran on the furthest point of the Mesopotamian plain, towards the sources of the Balikh. Beyond these were vague and unknown regions—Tidanum, Martu, the sea of the setting sun, the vast territories of Milukhkha and Mâgan.* Egypt, from the time they were acquainted with its existence, was a semi-fabulous country at the ends of the earth.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.