CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY

On a Letter to Ruskin.

About the name of Kate Greenaway there floats a perfume so sweet and fragrant that even at the moment of her death we thought more of the artist we admired than of the friend we had lost. Grateful for the work she had produced, with all its charm and tender cheerfulness, the world has recognised that that work was above all things sincere. And, indeed, as her art was, so were her character and her mind: never was an artist’s self more truly reflected in that which her hand produced. All the sincerity and genuine effort seen in her drawings, all the modesty, humour, and love, all the sense of beauty and of charm, all the daintiness of conception and realisation, the keen intelligence, the understanding of children, the feeling for landscape, with all the purity, simplicity, and grace of mind—all those qualities, in short, which sing to us out of her bright and happy pages—were to be found in the personality of the artist herself. All childhood, all babyhood, held her love: a love that was a little wistful perhaps. Retiring, and even shy, to only a few she gave her friendship—a precious possession. For how many are there who, gifted as she was, have achieved a triumph, have conquered the applause and admiration of two hemispheres, and yet have chosen to withdraw into the shade, caring for no praise but such as she might thankfully accept as a mark of what she was trying to accomplish, never realising (such was her innate modesty) the extent and significance of her success?

Here was a fine character, transparently beautiful and simple as her own art, original and graceful as her own genius. Large-hearted and right-minded, Kate Greenaway was gentle in her kindness, lofty and firm in principle, forgiving to the malevolent, and loyal to her friends—a combination of qualities happily not unrivalled among women, but rare indeed when united to attributes of genius.

It is true that what Kate Greenaway mainly did was to draw Christmas cards, illustrate a score or two of toy-books, and produce a number of dainty water-colour drawings; and that is the sum of her work. Why, then, is her name a household word in Great and Greater Britain, and even abroad where the mention of some of the greatest artists of England of to-day scarcely calls forth so much as an intelligent glance of recognition? It is because of the universal appeal she made, almost unconsciously, to the universal heart.

All who love childhood, even though they may not be blessed with the full measure of her insight and sympathy, all who love the fields and flowers and the brightness of healthy and sunny natures, must feel that Kate Greenaway had a claim on her country’s regard and upon the love of a whole generation. She was the Baby’s Friend, the Children’s Champion, who stood absolutely alone in her relations to the public. Randolph Caldecott laboured to amuse the little ones; Mr. Walter Crane, to entertain them. They aimed at interesting children in their drawings; but Kate Greenaway interested us in the children themselves. She taught us more of the charm of their ways than we had seen before; she showed us their graces, their little foibles, their thousand little prettinesses, the sweet little characteristics and psychology of their tender age, as no one else had done it before. What are Edouard Frère’s little children to hers? What are Fröhlich’s, what are Richter’s? She felt, with Douglas Jerrold, that ‘babes are earthly angels to keep us from the stars,’ ….

One of the charms, as has been said, most striking in the character of ‘K. G.’ (as she was called by her most intimate friends and relatives) was her modesty. A quiet, bright little lady, whose fame had spread all over the world, and whose books were making her rich, and her publisher prosperous and content—there she was, whom everybody wanted to know, yet who preferred to remain quite retired, living with her relatives in the delightful house Mr. Norman Shaw had designed for her—happy when she was told how children loved her work, but unhappy when people who were not her intimate friends wanted to talk to her about it. She was, therefore, so little seen in the world that M. Arsène Alexandre declared his suspicion that Kate Greenaway must really have been an angel who would now and then visit this green earth only to leave a new picture-book for the children, and then fly away again. She has flown away for ever now; but the gift she left behind is more than the gift of a book or of a row of books. She left a pure love of childhood in many hearts that never felt it before, and the lesson of a greater kindness to be done, and a delight in simple and tender joys. And to children her gift was not only this; but she put before them pictures more beautiful in their way and quaint[4] than had ever been seen, and she taught them, too, to look more kindly on their playmates, more wisely on their own little lives, and with better understanding on the beauties of garden and meadow and sky with which Heaven has embellished the world. It was a great deal to do, and she did it well—so well that there is no sadness in her friends’ memory of her; and their gratitude is tinged with pride that her name will be remembered with honour in her country for generations to come.

What Kate Greenaway did with her modest pencil was by her example to revolutionise one form of book-illustration—helped by Mr. Edmund Evans, the colour-printer, and his wood-blocks, as will be shown later on. And for a time she dressed the children of two continents. The smart dress with which society decks out its offspring, so little consonant with the idea of a natural and happy childhood, was repellent to Kate Greenaway. So she set about devising frocks and aprons, hats and breeches, funnily neat and prim, in the style of 1800, adding beauty and comfort to natural grace. In the first instance her Christmas cards spread abroad her dainty fancy; then her books, and finally her almanacks over a period of fifteen years, carried her designs into many countries and made converts wherever they were seen. An Englishman visiting Jules Breton, in the painter’s country-house in Normandy, found all the children in Greenaway costumes; for they alone, declared Breton, fitted children and sunshine, and they only were worthy of beautifying the chef-d’œuvres du bon Dieu.

SISTERS. ‘Girl with blue sash and basket of roses, with a baby.’

Indeed, Kate Greenaway is known on the Continent of Europe along with the very few English artists whose names are familiar to the foreign public—with those of Millais, Leighton, Burne-Jones, Watts, and Walter Crane—being recognised as the great domestic artist who, though her subjects were infantile, her treatment often elementary, and her little faults clear to the first glance, merited respect for originality of invention and for rare creative quality. It was realised that she was a tête d’école, the head and founder of a school—even though that school was but a Kindergarten—the inventor of a new way of seeing and doing, quite apart from the exquisite qualities of what she did and what she expressed. It is true that her personal identity may have been somewhat vague. An English customer was once in the shop of the chief bookseller of Lyons, who was showing a considerable collection of English picture-books for children. ‘How charming they are!’ he cried; ‘we have nothing like them in France. Ah, say what you like—Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway are true artists—they are two of your greatest men!’ It was explained that Kate Greenaway was a lady. The bookseller looked up curiously. ‘I can affirm it,’ said the visitor; ‘Miss Greenaway is a friend of mine.’ ‘Ah, truly?’ replied the other, politely yet incredulous. Later on the story was duly recounted to Miss Greenaway. ‘That does not surprise me,’ she replied, with a gay little laugh. ‘Only the other day a correspondent who called himself “a foreign admirer” sent me a photograph of myself which he said he had procured, and he asked me to put my autograph to it. It was the portrait of a good-looking young man with a black moustache. And when I explained, he wrote back that he feared I was laughing at him, as Kate is a man’s name—in Holland.’

But if her personality was a ‘mystification’ to the foreigner, there was no doubt about her art. In France, where she was a great favourite, and where her extensive contribution of drawings to the Paris Exhibition of 1889 had raised her vastly in the opinion of those who knew her only by her picture-books, she was cordially appreciated. But she had been appreciated long before that. Nearly twenty years earlier the tribute of M. Ernest Chesneau was so keen and sympathetic in its insight, and so graceful in its recognition, that Mr. Ruskin declared to the Oxford undergraduates that no expressions of his own could vie with the tactful delicacy of the French critic. But in his lecture on ‘The Art of England’ (Fairyland) Ruskin found words to declare for himself that in her drawings ‘you have the radiance and innocence of reinstated infant divinity showered again among the flowers of English meadows.’ And privately he wrote to her: ‘Holbein lives for all time with his grim and ugly “Dance of Death”; a not dissimilar and more beautiful immortality may be in store for you if you worthily apply yourself to produce a “Dance of Life.”’

The touchstone of all art in which there is an element of greatness is the appeal which it makes to the foreigner, to the high and the low alike. Kate Greenaway’s appeal was unerring. Dr. Muther has paid his tribute, on behalf of Germany, to the[6] exquisite fusion of truth and grace in her picture-books, which he declared to be the most beautiful in the world; and, moreover, he does justice to her exquisite feeling for landscape seen in the utmost simplicity—for she was not always drawing children. But when she did, she loved the landscape setting almost, if not quite, as much as the little people whom she sent to play in it.

From a Pencil Sketch in the possession of Lady Pontifex.

..Yet Kate could draw an eye or the outline of a face with unsurpassable skill: firmness and a sense of beauty were among her leading virtues. The painter with whom she had most affinity was perhaps Mr. G. D. Leslie, for her period and treatment are not unlike. …

CHAPTER II

EARLY YEARS: BIRTH—AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF CHILDHOOD—FIRST VISIT TO ROLLESTON—LOVE OF FLOWERS—FAMILY TROUBLE—EVENING PARTIES AND ENTERTAINMENTS.

On a Letter to Ruskin.

Kate Greenaway was born at 1, Cavendish Street, Hoxton, on the 17th day of March 1846. She was the daughter of John Greenaway and of his wife, Elizabeth Jones. John Greenaway was a prominent wood-engraver and draughtsman, whose work is to be found in the early volumes of the Illustrated London News and Punch, and in the leading magazines and books of the day. His paternal grandfather was also the forebear of the artist, Mr. Frank Dadd, R.I., whose brother married Kate’s sister. …

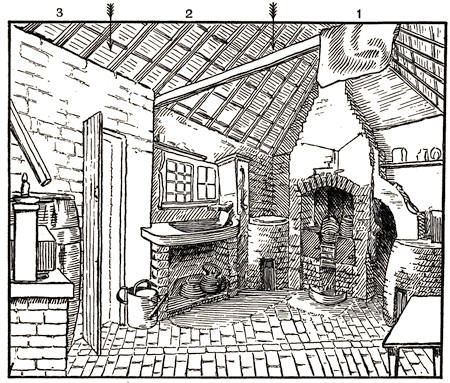

IN THE CHAPPELLS’ COTTAGE AT ROLLESTON—THE KITCHEN.

An early drawing by Kate Greenaway.

(See No. 1 on Sketch Plan.)

[11)

At Aunt Wise’s house Mrs. Greenaway was taken seriously ill, and it was found necessary to put little Kate out to nurse. Living on a small cottage farm in Rolleston[1] was an old servant of Mrs. Wise’s, Mary Barnsdale, at this time married to Thomas Chappell. With the Chappells lived Mary’s sister, Ann. It was of this household that Kate became an important member, and forthwith to the child Mary became ‘Mamam,’ her husband ‘Dadad,’ and her sister Ann ‘Nanan.’ This was as soon as she found her tongue. Among her earliest recollections came a hayfield named the ‘Greet Close,’ where Ann carried Kate on one arm, and on the other a basket of bread and butter and cups, and, somehow, on a third, a can of steaming tea for the thirsty haymakers—which tells us the season of the year. Kate was sure that she had now arrived at the age of two, and for the rest of her life she vividly remembered the beauty of the afternoon, the look of the sun, the smell of the tea, the perfume of the hay, and the great feeling of Happiness—the joy and the love of it—from her royal perch on Ann’s strong arm.

SKETCH OF THE KITCHEN AT ROLLESTON.

Showing the disposition of the apartment pictured in the three coloured illustrations.

Another remembrance is of picking up tiny pebbles and putting them into a little round purple-and-white basket with another little girl named Dollie, who was engaged in the same serious business with another purple-and-white basket. Kate was dressed in a pink cotton frock and a white sun-bonnet—she would have sworn, she tells us, to the colours half a century later, under cross-examination if necessary. Indeed, she seems never to have forgotten the colour of anything her whole life long.

But great as was the joy of tiny pebbles and of playmate Dollie, far greater was the happiness inspired by the flowers, with which she struck up friendships that were to last to her life’s end. There was the snapdragon, which opened and shut its mouth as she chose to pinch it. This she ‘loved’; but the pink moss rose,[12] which grew by the dairy window, she ‘revered.’ It grew with the gooseberry bushes, the plum tree, and the laburnum in the little three-cornered garden near the road. Then there was a purple phlox on one side of the gate and a Michaelmas daisy on the other side; and outside the gate (she put this into a picture years afterwards, and to her indignation was laughed at for it) grew a wallflower. But though she loved and revered the garden flowers, they were never to her what those were which grew of their own free will in the fields and hedgerows. There were the large blue crane’s-bill, the purple vetch, and the toad-flax, and, above all others, the willow-herb, which to her sisters and brother was ‘Kitty’s flower.’ These were the prime favourites, and, in the absence of the most elementary botanical knowledge, had to be christened ‘my little blue flower,’ ‘yellow dragon’s-mouth,’ or what not, for private use.

Farther away were the more rarely visited fairylands of the Cornfield and the Flower-bank, only to be reached under Ann’s grown-up escort when she was free of a Sunday. In the first, where the corn-stalks grew far above Kate’s head, the enchanted vistas reached, so it seemed, away for ever and ever, and the yellow avenues were brilliant with pimpernels, pansies, blue and white veronica, tiny purple geraniums, the great crimson poppies, and the persistent bindweed, which twined up the stems of the wheat. But the Flower-bank was better still—a high raised pathway which sloped down to a field on the one side and what was to her a dark, deep stream on the other, with here and there stiles to be climbed and delightfully terrifying foot-planks to be crossed; then through a deep, shady plantation until a mill was reached, and right on, if one went far enough, to the river Trent itself. Then, in the plantation grew the large blue crane’s-bill, the purple vetch, and the large white convolvulus, which with the vetch trailed over the sloe and blackberry bushes. And up in the trees cooed wood-pigeons; and, in the autumn, all sorts of birds were gathered in view of flights to warmer lands. Round the mill wound the little river Greet, with forget-me-nots on the banks and overhanging apple trees, from which apples, falling off in the autumn, would float away and carry with them Kate’s baby thoughts on and on to the sea, and so to the new and wonderful world of the imagination which was to be her heritage, and which she was to share with children yet unborn.

THE KITCHEN PUMP AND OLD CHEESE PRESS, ROLLESTON.

Early drawings by Kate Greenaway.

(See Nos. 2 and 3 on Sketch Plan.)

One thing only marred her pleasure, one note of melancholy discord on these Sunday morning walks—the church bells, which from earliest childhood spoke to her of an undefined mournfulness lying somewhere in the background of the world of life and beauty. She had heard them tolled for the passing of some poor soul, and ever after that they took the joy out of her day for all their assumption of a gayer mood.

As Kate grew a year or two older, another prime entertainment was to rise at five o’clock in the morning and go off with Ann to the ‘Plot’ to fetch the cows. The ‘Plot’ was a great meadow to which all the Rolleston cottagers had the right to send their cows, the number of beasts being proportioned to the size of the cottage. The Chappells sent three, Sally, Strawberry, and Sarah Midgeley, and the sight was to see Ann running after them—Ann, tall and angular, running with great strides and flourishing a large stick which she brought down with sounding thwacks on to tough hides and protruding blade-bones. The cows were evil-minded and they resented uncalled-for interference with their morning meal. They were as determined to stay in the plot as Ann was to get them out of it; sometimes, indeed, so determined were they on defiance that they would wander into the ‘High Plot,’ and then their disgrace and punishment were terrible to behold. ‘Get along in, ye bad ‘uns,’ she would cry in her shrill voice, and down the stick would come; until at last, hustling each other from where the blows fell thickest, and running their horns into each other’s skin, while little Kate grew sick with terror, they were at last marshalled to the milking-place, and peace would reign once more.

After a year or two at Rolleston, Kate was taken back to London, to Napier Street, Hoxton, whither the Greenaways had now moved.

Up to this time the family had been in easy circumstances, but trouble was now to come. Mr. Greenaway had been engaged to engrave the illustrations for a large and costly book. The publishers failed and he never received a penny of his money. There was nothing for it but to make the best of a bad job, and Mrs. Greenaway was not one to be daunted. The family was removed to Upper Street, Islington, opposite the church, and while her husband sought further work, Mrs. Greenaway courageously set up shop and sold lace, children’s dresses, and all kinds of fancy goods. The venture was successful, and the children found nothing to complain of in their new surroundings.

Fashioned out of the middle portion of an old Elizabethan country house, the wings being likewise converted into two other small shops and the rooms apportioned accordingly, the new home was a very castle of romance. To the Greenaways fell the grand staircase and the first floor, with rambling passages, several unused rooms, too dilapidated for habitation, and weird, mysterious passages which led dreadfully to nowhere. At the back was a large garden, the use of which was held in common by the three families.

It was in Islington that Kate had her first taste of systematic education, from Mrs. Allaman, who kept an infants’ school—an old lady with a large frilly cap, a frilly muslin dress, a scarf over her shoulders, and a long apron. Here she learned her letters and how to use needle and cotton. On the whole, she liked the old lady, but all her life long she could feel the sounding tap of her admonitory thimble on her infant head in acknowledgment of a needle negligently and painfully presented point first to the mistress’s finger.

Of all her relations Kate loved best her mother’s mother, ‘Grandma Jones,’ who lived in Britannia Street, Hoxton, in a house of her own. She was a bright, clever old lady, with a sharp tongue, fond of shrewd sayings and full of interesting information. Not her least charm was that she always had Coburg loaves for tea, beautiful toast, raspberry jam, and honey. Of Grandfather Jones, Kate writes:

My mother’s father was a Welshman. She used to tell us he belonged to people who were called Bulldicks because they were big men and great fighters, and that they used as children to slide down the mountains on three-legged milking-stools. He was very bad-tempered and made them often very unhappy, but he was evidently intellectual and fond of reading. My mother has often told me how he read Sir Charles Grandison, and she used to stand behind his chair unknown to him and read it also over his shoulder.

On her twentieth birthday he insisted upon giving a party, because he said he should die before she was twenty-one, and he did.

Other relations of whom the little Greenaways saw a great deal were their aunts Rebecca, a bookbinder, and Mary, a wood-engraver. Aunt Mary was a great favourite because she always had bread and treacle or bread and butter and sugar for tea. But on Sundays there were oranges and apples, cakes and sweets, with The Pilgrim’s Progress, John Gilpin, Why the Sea became Salt[15] to follow. Especially from Aunt Mary, later on, did Kate derive her deep love of poetry.

It was in Aunt Mary’s company that a certain disastrous walk was taken up the City Road one enchanted night, dimly lighted by the stars overhead and by the red and blue chemist’s-bottles in the windows below. Sister Fanny was of the company, and both the little girls, overcome by the splendours of the scene, tumbled off the curb into the road, and arrived home muddy and disgraced. And the whole was the more terrible because Fanny was resplendent—(for there seems no limit to Kate’s sartorial recollection)—Fanny was resplendent in ‘a dark-red pelerine, with three rows of narrow velvet round the cape, and a drab plush bonnet, trimmed with chenille and red strings; and Kate in a dark-red frock, a bonnet like her sister’s, and a little grey cloth jacket scalloped at the edge, also bound and trimmed with red velvet. And each had a grey squirrel muff.’ From which particularity we see how the artist in posse was already storing her mind with matters which were to be of use to her in garment-designing in time to come. As we proceed, we shall more and more realise how important a factor in her artistic development was this early capacity for accurate observation, ravenously seizing upon and making her own the infinitely little details of her childish experiences. It was the vividness of these playtime impressions that made their recall possible at such period as her life-work had need of them.

There was another aunt, Mrs. Thorne, Mrs. Greenaway’s youngest sister, who lived at Water Lane, near the River Lee, of whom Kate by no means approved, for hers was an extremely ill-ordered household. But though visits there left a very disagreeable impression, they were big with something of delightful import which had its development many years later. It illustrates well how impressions absorbed in early years coloured the artist’s performances in far-off days to come.

Aunt Thorne’s garden was overrun with a glory of innumerable nasturtiums. They were, in Kate’s own words, the ‘gaudiest of the gaudy,’ and she ‘loved and admired them beyond words.’ She was possessed by their splendour, and finally got them visualised in a quite wonderful way in a dream with a background of bright blue palings. For many a long year she bore the entrancing vision about with her, and then gave it permanent expression for the delight of thousands in her picture of Cinderella fetching her[16] pumpkin. The visits, therefore, which were so distasteful at the time were neither without result nor unimportant. Moreover, the nasturtium dream brought to Kate, who as a child was a great dreamer, a new experience. Two or three years before she had dreamed that she had come to a cottage in a wood and knocked at the door. It was opened by an old woman whose face suddenly assumed an expression so awful that she awoke frightened and trembling. In the nasturtium dream there was just such another cottage with just such another door, at which, after she had passed through the garden and had absorbed its beauties, she also knocked. Then in a moment she knew that the door would be opened by the old woman with the horrible face of three years before. A deadly faintness seized upon her and she again woke in horror. This was her first experience of a dream within a dream.

Many of her dreams were recurrent and are common enough to childhood. One constantly repeated vision, she tells us, brought to her her dearly loved father. She would dream that, gazing into his face, the countenance would change and be, not his face, but another’s. With this change would come an agony of misery, and she would desperately tear off the false face, only to be confronted by another and yet another, but never his own, until in mercy she awoke and knew that the terrible mutations were as unreal as they were terrifying. Again, an often-repeated dream was of falling through water, down, down past the green weeds, slowly, slowly, sink, sink, with a sort of rhythmic pause and start until the bottom was reached, and she gently awoke. Or something would be in pursuit, and just as capture was imminent, she would feel that she could fly. Up, up she would soar, then float down over a steep staircase, out at one window and in at another, until she found herself lying in an ecstasy awake and wanting the delightful experience all over again.

Kate’s childhood seems, on the whole, to have been happy enough, not so much in consequence of her surroundings as of her temperament. Writing to Miss Violet Dickinson forty years later, she says:

Did you ever know Mr. Augustus Hare? I find his book so very interesting. I once was at the Locker-Lampsons’ when he was there. I did not feel very sympathetic then, but now I read his Life, I feel so very sorry for the poor unhappy little child he was. And the horrid stern people he lived with—it makes me feel I don’t know what, as I read….

I can’t think how people can be hard and cruel to children. They appeal to you so deeply. I had such a very happy time when I was a child, and, curiously, was so very much happier then than my brother and sister, with exactly the same surroundings. I suppose my imaginary life made me one long continuous joy—filled everything with a strange wonder and beauty. Living in that childish wonder is a most beautiful feeling—I can so well remember it. There was always something more—behind and beyond everything—to me; the golden spectacles were very very big.

Late on in life, too, she used to compare the ‘don’t-much-care’ attitude of the modern child with the wildness of her own enjoyments and the bitterness of her own disappointments. It was a complaint with her that the little girl in Jane Taylor’s poems who cried because it rained and she couldn’t go for a drive was a child of the past, whereas her modern representative, surfeited with treats, takes her disappointments stoically, or at least apathetically, and never sheds a tear. There may have been some grounds for the comparison, but probably what she missed in the modern child was the latent artistic emotion with which she had been endowed at birth. For this power of joyful realisation had its necessary converse: the very intensity of anticipation which made it necessary for treats to be concealed from her until the morning of their occurrence, and her wild abandonment to pleasure when it came, found its counterpart in fits of depression and gloom, such as do not come to the humdrum and unimaginative child. At such times she would make up her mind not only to be not happy, but to be aggressively gloomy. One day, indeed, she went so far as to announce at breakfast that she did not intend to smile the whole day long, nor indeed to utter a single word. The announcement was received with derisive laughter, for the others knew it was only Kate’s way, and that at the afternoon party which was imminent she would be the gayest of the gay. And the worst of it was that Kate knew in her heart of heart that they were right, and that when the time came she would laugh and be happy with the rest.

One of these well-remembered gatherings was the B.’s party, an annual affair, held in a long rambling furniture shop, full of dark corners, weird shadows, and general mystery. Here it was, year in, year out, that they met the little Miss C.’s, who, full of their own importance, seeing that they were much better dressed than the other children, annually sat silent, sulky, and superior.[18] Here too disported himself the debonnaire Johnny B., a very wild boy, who generally managed to break some furniture, and had such dexterity in the lancers that he could shed his shoes as he went round and get into them again without stopping. Fate claimed him for the Navy, and he passed out of their lives in a midshipman’s uniform.

Another was Mr. D.’s annual Twelfth Night party, notable for its very big Twelfth cake, its drawing for king and queen, and its magic-lantern. Kate never became queen, but at Miss W.’s party, quite the most important of the year, she once had her triumph. According to her own account—

It was some way off; even now I remember the shivery feeling of the drive in the cab, and the fear that always beset me that we might have gone on the wrong day. There was Miss W., Miss W.’s brother, Miss W.’s aunt, and Miss W.’s mother. Miss W. taught my eldest sister Lizzie music, and all her pupils were invited once a year to this party, their sisters also, but no brothers—at least, two brothers only I ever remember seeing there.

On a Letter to Ruskin.

There was one big tomboy sort of girl, with beautiful blue eyes and tangled fair hair, who used to have a grown-up brother come to fetch her; this girl I loved and admired intensely, and never spoke to her in my life. She had merry ways and laughing looks, and I adored her. The other brother was the cause of my one triumph. One party night there was just this little boy—among all the girls—and tea over and dancing about to begin, the boy was led to the middle of the room by Miss W., and told out of all the girls to choose his partner for the first dance. He took his time—looked slowly round the room, weighing this and that, and, to my utter discomfiture and dire consternation, he chose me—moment of unwished triumph—short-lived also, for he didn’t remain faithful, but fell a victim later on to the wiles of some of the young ladies nearly twice his age. I remember I was much relieved, became fast and devoted friends with a nice little girl, passed an agreeable evening, and remember at supper-time surreptitiously dropping an apple-tart I loathed behind a fender. I daresay it was good really, but it was tart with the tartness of lemonade and raspberryade, two things I disliked at that time.

But delightful as were these private parties, they were as[19] nothing compared with the rarer visits to the theatres or other places of entertainment. On these never-to-be-forgotten occasions Mr. Greenaway, whose work was chiefly done away from home, would turn up quite unexpectedly at tea-time, would pretend that he had come home for nothing in particular, and would playfully keep the eager children on the tenterhooks of expectation. But it was only part of a playful fraud, for they knew well that nothing would tempt him early from his work but some thrilling treat in store for them. What delight there was, when finally the secret of their destination leaked out, to scramble over tea, hurry on best clothes, thread dark streets, and finally blink their way into the magic circle of the blazing theatre itself, with its fascinating smell of oranges and gas, the scraping of violins, and all the mysterious titillations of the expectant senses.

Kate’s first taste of the theatre was Henry the Fifth at Sadler’s Wells. Then came the Midsummer Night’s Dream, Henry the Fourth, The Lady of Lyons, and (at Astley’s) Richard the Third. It was at Astley’s, too, when she must have been several years older, that she saw a piece called The Relief of Lucknow, in which General Havelock rode on to the stage on a beautiful white horse. This made so great an impression upon her that she burst into tears, whereupon her sister said she was ‘a silly’ and her father said she wasn’t; for the awful tragedy of the Indian Mutiny was at that time filling everybody’s thoughts, and with the details of it she had grown terribly familiar by poring over the pictures in the Illustrated London News. Moreover, her imagination had stimulated her pencil at this time to make many dramatic drawings of ladies, nurses, and children being pursued by bloodthirsty sepoys; but the pencil was of slate, and consequently these earliest known drawings were wiped out almost as soon as executed.

Hardly less enchanting than these theatrical experiences were the days which brought them tickets for the Polytechnic or took them to the Crystal Palace. The former was not yet the haunt of Pepper’s Ghost, or of Liotard (in wax) on his trapeze, but it was quite enchanting enough with its Diving Bell and the goggle-eyed Diver, who tapped the pennies, retrieved from the green depths of his tank, on the sounding brass of his helmet. The Palace, with its Alhambra Courts, its great fountains, its tall water towers, and other innumerable delights, was an Abode of Bliss. Those were days in which, to her memory, the sun[20] seemed always to be shining, the sky always to be blue, and the hours never long enough for all their joyous possibilities. And, though the time had to come when the sun sometimes forgot to shine, and, when it did, threw longer shadows before her, Kate Greenaway never wholly forgot, but kept these joys alive in her heart for the enchantment of others.

WINTER, 1892.

From a water-colour drawing in the possession of Stuart M. Samuel, Esq., M.P.

CHAPTER III

CHILDHOOD IN ROLLESTON: EARLY READING—ADVENTURES IN LONDON STREETS—A COMMUNITY OF DOLLS—BUCKINGHAM PALACE—LIFE IN ROLLESTON—EDUCATION—BROTHER AND FATHER.

Illustration: On a Letter to Ruskin.

When Kate was midway between five and six years of age, the family moved into a larger house and shop nearer to Highbury. Here they fairly established themselves, and here was the home of her recollection when she looked back on her childhood.

Then a new world opened to her, a new, boundless world, unfenced about with material walls, illimitable, inexhaustible—the world of books and measureless imagination. Of a sudden, to her mother’s and her own great happiness and surprise, she found that she could read! First came the two-a-penny Fairy Tales in coloured paper covers. There were larger ones for a penny, but the halfpenny ones were better. Pepper and Salt was one of the most enjoyably and delightfully afflictive. Who that has read it in tender years can ever forget how the Cruel Stepmother kills Salt and buries her, or the mysterious voice that chanted—

‘She drank my blood and picked my bones,

And buried me under the marble stones.’

Kate never forgot them, as, indeed, she never forgot Bluebeard, or Toads and Diamonds, or Beauty and the Beast. But, although she never forgot them, she never remembered them too well. The delicious excitement could always be renewed. A hundred times she had heard Bluebeard call in his awful voice to Fatima to come down. A hundred times Sister Ann had cried her shrill reply: ‘I see the sky that looks blue and the grass that looks green.’ A hundred times the little cloud of dust had risen, and[22] the brothers had come in the nick of time to save her. But, at the hundredth reading, Kate’s fear was as acute and her relief as great as at the first.

Other favourites were Frank, Harry, and Lucy, The Purple Jar, The Cherry Orchard, Julianna Oakley, The Child’s Companion, and Line upon Line.

Then there were the verses of Jane and Ann Taylor, rendered especially delightful by Mrs. Greenaway’s dramatic rendering at bedtime—‘Down in a green and shady bed,’ ‘Down in a ditch, poor donkey,’ and ‘Miss Fanny was fond of a little canary.’ The last harrowed Kate with an intense sorrow, as indeed it did to the day when she set to work to illustrate it for the joy and delight of a later generation in a volume dedicated to Godfrey, Dorothy, Oliver, and Maud Locker.[2] Others which she could never hear too often were ‘Greedy Richard,’ ‘Careless Matilda,’ ‘George and the Chimney-Sweep,’ ‘Dirty Jim,’ ‘Little Ann and her Mother,’ and ‘The Cow and the Ass.’

‘Take a seat,’ said the Cow, gently waving her hand.

‘By no means, dear Madam,’ said he, ‘while you stand.’

Then showing politeness, as Gentlemen must,

The Ass held his tongue that the Cow might speak first.

But one book there was which, whilst it delighted the rest, depressed little Kate horribly and miserably, though she would never confess it, partly out of loyalty to her father and partly from shame at what she felt might be regarded as a foolish weakness. This was a book of rhymes for which Mr. Greenaway had engraved the wood-blocks. It contained the ‘Courtship, Life, and Death of Cock Robin and Jenny Wren’; ‘The Three Bears’; ‘The Little Man and the Little Maid’; ‘The Wonderful History of Cocky Locky, Henny Penney, and Goosey Poosey’; and a story of a Goose and her three daughters, Gobble, Goosey, and Ganderee, which began

A Goose who was once at the point of death

She called her three daughters near. ..

Dolls

.Fortunately she had not a few distractions. There were her dolls, which ranged from the little giant ‘Gauraca’ (given to Kate for learning a piece of pianoforte music so entitled, then in vogue), so huge—more than a yard and a quarter long—that she could only be carried with legs trailing on the ground, to the little group of Dutch mannikins of which half-a-dozen could be grasped in one hand. By right of bulk Gauraca claimed precedence. She wore the discarded clothes of brother John, the tucks in which had to be let down to make them big enough, and took full-sized babies’ shoes. She was a wonder, not indeed altogether lovable; rather was she of value as a stimulator of covetous feelings in others. Below Gauraca came dolls of all sorts and sizes, too many for enumeration, but all of importance, seeing that on their persons were performed those tentative experiments which were to colour the work of twenty years later.

On these dolls Kate dilates at some length, and the gist of her record is this. Least in size though first in rank came the Royal group, with Queen Victoria (who had cost a halfpenny) as its centre, supported by Prince Albert (also a halfpenny) appropriately habited in a white gauze skirt trimmed with three rows of cerise satin, and, for further distinction and identification, a red ribbon tied across his shoulder and under his left arm. These garments could only be removed by an actual disintegration. The Royal circle was completed by the princes and princesses at a farthing apiece. Their dresses were made from the gauze bonnet linings just then going out of fashion, and such scraps of net and ribbon as had proved unsaleable. …

After the wooden dolls, with their crude and irremovable garments, came the far more human-looking effigies in china, which populated the cupboard in the little girls’ bedroom. Their clothes were all exquisitely made by Kate, and were all removable. They took their walks abroad on the mantelpiece. Their hats[28] were made of tiny straw-plaits trimmed with china ribbons and the fluffy down culled from feathers which had escaped from the pillows. They revelled in luxurious gardens made of fig boxes filled with sand collected on Sunday walks to Hampstead Heath, and planted with the tiniest of flowering plants, which often had to be replaced, as they would not thrive in the uncongenial soil. Furniture was hard to come by at a farthing a week, which was Kate’s income at this time, but twenty-four weeks’ saving got a sixpenny piano, for the sake of which the sacrifice of other expensive pleasures during that period was considered not unreasonable. Once indeed Aunt Aldridge came to town and presented the dolls with a work-table, but so great a piece of good fortune never again befell.

Later there were Lowther Arcadian dolls at fourpence halfpenny apiece, but these like the royal group were short-lived and ephemeral. They passed away so rapidly that memory lost their identity, whereas ‘Doll Lizzie,’ made of brown oak, legless, armless, and devoid of paint, and ‘One-eye,’ equally devoid of paint, half-blind, and retaining but one rag arm, were seemingly immortal, and were more tenderly loved than all, notwithstanding the fact that their only clothing consisted of old rags tied round them with string. These remnants went to bed with the little girls, and enjoyed other privileges not accorded to the parvenues.

London, as we see, was now the home of Kate Greenaway, but fortunately there was Rolleston and the country always in the background as a beautiful and fascinating possibility; and it was rarely that a year passed without a visit, though now and again not enough money had been saved to make the thing feasible.

In Kate’s own simple words:

In these early days all the farm things were of endless interest to me. I used to go about in the cart with Dadad, and Nancy to draw us. He thought wonderful things of Nancy—no pony was like her. I shared his feeling, and when my Uncle Aldridge used to inquire how the high-mettled racer was, I felt deep indignation. There was no weight Nancy couldn’t draw—no speed she could not go at (if she liked), but there was no need on ordinary occasions—there was plenty of time. The cart had no springs—it bumped you about; that didn’t matter to me. Sometimes we used to go to Southwell to get malt. This was a small quiet town two and a half miles off, and the way to drive was through green lane-like roads. It took a good while. Nancy went at a slow jog-trot; I didn’t mind how long it took, it was all a pleasure.[29] There was an old cathedral called Southwell Minster, with quaint old carvings in stone and old stained-glass windows which they said were broken and buried in Cromwell’s time so as to save them. Southwell now possesses a Bishop, but it did not then. Then we used to go to the ‘Plot,’ where all the cottage people had land, to get potatoes or turnips. At hay-time and harvest the cart had one of those framework things fitted on, and Nancy fetched corn or hay.

I had a tiny hayfork, a little kit to carry milk in, and a little washing-tub, all exactly like big real ones, only small. I washed dolls’ things in the tub, and made hay with the fork, and carried milk in the kit.

Then, besides Nancy, there were the three cows, numerous calves, two pigs, two tortoiseshell cats, and a variable number of hens. Variable, for barring ‘Sarah Aldridge,’ the tyrant of the yard, their lives were sadly precarious, and the cooking-pot insatiable. ‘Sarah Aldridge,’ so named after the giver, was a light-coloured, speckled, plump hen with a white neck—a thoroughly bad character, a chartered Jezebel of a fowl, bearing a charmed and wholly undeserved existence. She took, says Kate Greenaway, the biggest share of everything, chased all the other hens, and—crowed.

Stowed somewhere in Mary Chappell’s memory was the old proverb—

A whistling woman and a crowing hen

Are neither good for God nor men.

‘Sarah Aldridge’ crowed. And when she crowed Mary became strangely moved with mingled rage and fear. She would fling down whatever she was doing. She would fly after ‘Sarah’ breathing dreadful threats. She would run her well-nigh out of her life, nor desist until she was compelled for want of breath. Then she would fall into an awe-stricken state, which she called a ‘dither,’ convinced that because of this monstrous breach of nature some terrible thing would be sure to happen.

But, notwithstanding her superstitions, Mrs. Chappell was a truly worthy woman,—one of the noblest. Indeed, Kate Greenaway always insisted that she was the kindest, most generous, most charitable, the cheerfullest, and most careful woman she had ever known. To quote her words, ‘in all things she was highest and best.’ She meant nothing derogatory to her husband when she told every one before his face that he was a ‘poor creature.’ He entirely agreed. There was no hint at his being ‘wanting’ in any particular, but rather that Providence was at fault in not vouchsafing him a full measure of health and[30] strength. Indeed, he felt rather distinguished than otherwise when his wife drew attention to his infirmities. He was one of those who thoroughly enjoyed his bad health.

It was a rule of life with Mrs. Chappell never to speak ill of her neighbours. ‘Ask me no questions and I will tell you no stories,’ was the letter always on her lips, and the spirit of charity was always in her heart. She combined the utmost generosity with a maximum of carefulness. She did not know how to be wasteful. She had a merry heart, and Kate always maintained that it was through her that she learnt to be in love with cheerfulness. So that more than one unmindful generation has since had cause to bless the memory of Mary Chappell. Her real name was Phyllis, Phyllis Barnsdale, previous to her marriage. Before going to Rolleston she had been in service with a Colonel, a friend of Lord Byron’s and a neighbour of his at Newstead Abbey. Of her reminiscences Kate retained just two things. Of Byron, that his body was brought home in spirits of wine. Of the Colonel, that he was so short-sighted that the groom only rubbed down his horse on the near side, secure that the half-heartedness of his service would never be discovered.

When Kate first went to Rolleston the Fryers’ farm had passed into the hands of a married daughter, Mrs. Neale, whose husband, an idle, good-natured, foolish man, smoked and drank whilst the butcher-business slipped through his fingers. In Kate’s earliest days they were seemingly prosperous enough, and one of the first things the little Greenaways had to do on arrival at Rolleston was to make an odd little morning call at ‘The House,’ where they were regaled with cowslip wine and sponge-cakes. This was the etiquette of the place: it was the respect due from Cottage to Farm.

The Fryers’ garden was, in Kate’s own words years afterwards, ‘my loved one of all gardens I have ever known,’ and that was saying a good deal, for it would be hard to find anywhere a greater lover of gardens than she was. It was her real Paradise. Round the windows of ‘The House’ grew the biggest and brightest convolvuluses in the world (at least in the world she knew)—deep blue blossoms with ‘pinky’ stripes and deep pink blossoms with white stripes. Her intimacy with them told her every day where the newest blooms were to be found. Across the gravel path on the left as you emerged from ‘The House’ was a large oval bed, with roses, pinks, stocks, sweet Sultans, the brown scabious, white lilies, red lilies, red fuchsias, and in early summer, monster tulips, double white narcissus, peonies, crown imperials, and wallflowers. Indeed, all lovely flowers seemed to grow there. And the scent of them was a haunting memory through life. Then there were the biggest, thickest, and bushiest of box borders, nearly a yard high, so thick and solid that you could sit on them and they never gave way. These bounded the long gravel walk which led straight down to the bottom of the garden, and along which grew flowers of every lovely shape and hue. Beyond them on the left was the orchard—apples, pears, plums, and bushy filberts; on the right the kitchen garden—currant bushes with their shining transparent bunches, red and white, gooseberries, strawberries, feathery asparagus, and scented herbs such as good cooks and housewives love. It was an enchanted fairyland to the little Londoner and had a far-reaching influence on her life and work. Later on her letters teemed with just such catalogues of flowers. So great was her love for them that, next to seeing them, the mere writing down of their names yielded the most pleasurable emotions.

Another thing which greatly appealed to her was the spaciousness[32] of everything—the great house seemingly illimitable in itself, yet stretching out farther into vast store-houses and monster barns. For those were days when threshing machines were unknown and corn had to wait long and patiently to fulfil its destiny. Indeed, people took pride in keeping their corn, unthreshed, just to show that they were in no need of money. Then large bands of Irishmen wandered over the country at harvest-time, leisurely cutting the corn with sickles, for the machine mower was at that time undreamed of.

At the Neales’, too, there were birds innumerable—peacocks strutting and spreading their tails, guinea-fowls, turkeys with alarming voices and not less alarming ways, geese, pigeons, ducks, and fowls. All these things were in the early Rolleston days, but they did not last.

By degrees, through neglect and carelessness, the business drifted away from the Neales into more practical and frugal hands, and in the end they were ruined—wronged and defrauded by the lawyers, the Chappells believed, but in reality abolished by the natural process of cause and effect. Anyhow, the Chappells acted up to their belief, and with unreasoning loyalty gave them money, cows, indeed everything they had, until they were themselves literally reduced to existing on dry bread and were involved in the general downfall. In this Mary Chappell was, of course, the moving spirit, but her husband agreed with all she did, and took his poor fare without complaint.

But before the crash came there were many happy days and lively experiences. There was Newark market on Wednesdays, to which Mary Chappell always went with Mrs. Neale, sometimes, but rarely, accompanied by the latter’s husband. On special occasions Kate went too. Fanny, the brown pony, drew them in a lovely green cart. When Mr. Neale went, Mrs. Chappell and Kate sat behind. When he didn’t, Kate sat behind alone and listened to the two ladies talking about Fanny as if she were a human being, discussing her health, her likes and dislikes of things she passed on the road, in full enjoyment of the never-failing topic of ‘the old girl.’

There was a good deal of preliminary interest about these expeditions. There was the walk up to ‘The House’ with Mary Chappell heavily laden with baskets of butter on each arm. Mary was no ordinary butter-seller. She would no more have dreamed of standing in the butter-market to sell her butter than she would[33] have dreamed of selling it to the shops to be vended over the counter like ordinary goods. Only people who did not keep their pans properly clean would stoop to that. No, she ‘livered’ her own butter. She had her own regular customers who had had her butter for years, and they always wanted more than she could supply. The making of good butter and cheese was part of her religion. She would drop her voice and speak only in whispers of people—half criminals she thought them—whose puncheons were not properly cleansed, whose butter might ‘turn’ and whose cheese might ‘run.’

Arrived at ‘The House,’ they would find the green cart waiting before the door. Then a farm hand would stroll leisurely round with Fanny and put her into the shafts. Everything was done slowly at Rolleston, and bustle was unknown. Next would come Sarah Smith, the maid, with a basket after her kind. Then a help or out of-door servant, with another after his kind. A minute later some one bearing ducks or fowls with their legs tied. These went ignominiously under the seat, and took the cream, as it were, off Kate’s day. Their very obvious fate made her miserable, but she cajoled herself into something like happiness by imagining that someone might buy them ‘who didn’t want to eat them and would put them to live in a nice place where they could be happy.’

Mrs. Neale.

As the prospect of starting became more imminent, Mrs. Neale would arrive with the whip and a small basket. Then Mr. Neale, and the two young Fryer nephews who lived with them, would stroll round to see them off. At the last moment would arrive baskets of plums, apples, pears, and, perhaps, sage cheeses, and a start would then be made.

The five miles into Newark, through Staythorpe, Haverham, and Kelham, where the Suttons, to whom nearly all Rolleston belonged, lived at ‘The Hall,’ was a progress of great enjoyment and variety, for they knew not only all the people they met on the road, but all the animals and all the crops, and these had all to be discussed.

Arrived at Newark, Mrs. Neale was left at the inn, whilst Mary and Kate went their rounds with the butter. All the customers got to know Kate, and the little girl received a warm welcome year after year in the pretty red-brick, green-vine-clad courtyards with which Newark abounded. When the butter was sold the shopping came, and when all the necessary groceries and supplies had been laid in, a stroll through the market-place, where peppermints striped and coloured like shells were to be got. Why people bought groceries when they could afford peppermints Kate didn’t know.

In the market of course everything was on sale that could be imagined, from butter to boots, from pears to pigs, from crockery to calves. But it was the crockery that had a peculiar fascination for Mary, and many an unheard-of bargain made a hole in her thinly-lined pocket. These pots were from Staffordshire and became Kate’s cherished possession in after years.

At last there was the weary return to the inn-yard to find Mrs. Neale, who might or might not be ready to go home. Anyhow Fanny and the cart were always welcome enough when the time came to exchange the confusion and hubbub of the town for the quiet country roads again.

It didn’t matter what time they arrived home, Chappell would always be found watching for them at the gate. Tea was ready and they were hungry for it; Chappell, too, for he spent the whole afternoon on market days leaning over the gate. It was his one chance in the week of seeing his acquaintances as they passed to Newark, and it was his one chance of buying pigs. He had a weakness for pigs, and he would stop every cart that had a likely one on board. Sometimes he would have out a whole load, would bargain for half-an-hour, and then refuse to have one. Time was of no consequence to him, but the owner’s wrath would be great, for all the pigs that were wanted in Newark might be bought before he could arrive there. Then the cart would be driven away to a blasphemous accompaniment, leaving Chappell blandly smiling, placid and undisturbed. This would be repeated many times until the pigs arrived which took his fancy.

On great and rare occasions, Kate would go to market with Aunt Aldridge in a high dog-cart behind a spanking horse named Jack. Then she would have a taste of really polite society, and would be taken to dine in a big room at the chief inn with the leading farmers and their wives. For in the Nottinghamshire of[35] those days the farmers were in a large way, prosperous and with plenty of money to spend. It was quite a shock and surprise to her in after life to see farmers in other parts of the country little better than labourers. For this reason she never cared for Thomas Hardy’s books; she never could get on terms with his characters. But with George Eliot’s it was quite another matter. Mrs. Glegg, Mrs. Tulliver, Mrs. Poyser, and the rest, she had known all her life. They were old friends and she felt at home with them at once.

‘Dadad’ and Ann going to Church.

Kate was present at two great events at Rolleston—a fire and a flood. Here is her own account of them:— …

THE CHAPPELLS’ COTTAGE, FARM, AND CROFT AT ROLLESTON.

Drawn by Kate Greenaway when a young girl.

Next we have a glimpse of Kate making triumphant progresses in the corn-waggons and hay-carts as they rattled back empty to the fields. The corn-waggons, it must be admitted, had a drawback in the little dark beetles—‘clocks’ as the waggoners called them—which ran about and threatened her legs. But these were soon forgotten in the near prospect of a ride back perched high o …n the Harvest Home load, decked with green branches, while the men chanted—…

‘Mr.—— is a good man,

He gets his harvest as well as he can,

Neither turned over nor yet stuck fast,

He’s got his harvest home at last.

Hip, hip, hip, hurrah!’

And she loved to sit on the stile watching for the postman. In earliest days ‘he was an imposing person who rode on a donkey and blew a brass trumpet. If you wished to despatch a letter and lived alongside his beat you displayed it in your window to attract his attention. When he saw a letter thus paraded, he drew rein, blew a blast, and out you ran with your letter. If you lived off his route you had to put your letter in somebody else’s window. So with the delivery. Aunt Aldridge’s letters, for example, were left at the Chappells’ and an old woman got a halfpenny a letter for taking them up to the Odd House.’ In those days the postman was clearly not made for man, but man for the postman.

Once and once only Kate went fishing at the flour mill, which had its water-wheel on the Greet. She sketches the scene vividly in a few words. How lovely it all was, she tells us—the lapping of the water against the banks of the reedy river, the great heaps of corn, the husks, the floury sacks and carts, the white-coated millers, the clean white scent, and, above all, the excitement of looking out for the fish! What could be better than that? It was about as good as good could be, when of a sudden all was changed. There was a jerk of the rod, a brief struggle and a plunge, and there lay a gasping fish with the hook in its silly mouth, bleeding on the bank. What could be worse than that? It was about as bad as bad could be. The sun had gone in. The sky was no longer blue, and misery had come into the world. She loathed the task of carrying the poor dead things home to be cooked, and she refused to partake of the dreadful dish. It was all too sad. The pleasant river and the bright glorious days were all over for them and she was not to be comforted. And that was the end of Kate’s single fishing experience. Surely fate was in a singularly ironical mood when, in later years, it brought her[38] a letter of hypercritical remonstrance because of her supposed advocacy of what the writer considered a cruel and demoralising sport!

Indeed, we have only to read her rhyme of ‘Miss Molly and the little fishes’ in Marigold Garden to realise that her sentiments as a child remained those of the woman:

Oh, sweet Miss Molly,

You’re so fond

Of fishes in a little pond.

And perhaps they’re glad

To see you stare

With such bright eyes

Upon them there.

And when your fingers and your thumbs

Drop slowly in the small white crumbs,

I hope they’re happy. Only this—

When you’ve looked long enough, sweet miss,

Then, most beneficent young giver,

Restore them to their native river.

In this fashion the little ‘Lunnoner,’ as she was always called, got her fill of the country, and her intimacy with more or less unsophisticated nature—a love which was her prevailing passion throughout her life. …

THOMAS CHAPPELL (‘DADAD’).

Drawn in his old age by Kate Greenaway.

When Kate was six years old her brother John was born; and of course she remembered to her dying day all the clothes he ever had, and all those which she and her sisters had at the same time; and she notes the details of three of his earliest costumes which she remembered to good purpose. First, a scarlet pelisse, and a white felt hat with feathers; next, a drab pelisse and a drab felt hat with a green velvet rosette; and thirdly, he was resplendent in a pale blue frock, a little white jacket, and a white Leghorn hat and feather—all of which afterwards found resurrection in the Greenaway picture-books.

There was always a deep bond of sympathy between Mr. Greenaway and his little daughter, whom, by the way, he nicknamed ‘Knocker,’ to which it amused him to compare her face when she cried. Her devotion to her father doubtless had far-reaching results, for not only was Mr. Greenaway an accomplished engraver, but an artist of no mean ability. And there was a fascination and mystery about his calling which made a strong appeal to her imagination. On special occasions he would be commissioned to make drawings for the Illustrated London News, and then Kate’s delight would be unbounded. The subject might be of Queen Victoria at some such ceremony as the opening of Parliament; or sometimes of some more stirring occurrence—such, for example, as that which necessitated the long journey into Staffordshire to make sketches of the house and surroundings of the villainous doctor, William Palmer, the Rugeley murderer, an event which stood out in her memory as of supreme interest and importance.

Mr. Greenaway’s office, as long as Kate could remember, was 4, Wine Office Court, Fleet Street. There most of his work was done; but when, as frequently happened, there was a scramble to get the wood blocks engraved in time for the press, he would have to work the greater part of two consecutive nights. Then he would bring portions of his blocks home, distributing the less important sections among his assistants, so that the whole might be ready in the morning.

These were times of superlative pleasure to Kate. She would wake up about midnight and see the gas still burning outside in[40] the passage. This meant that her father was hard at work downstairs. About one o’clock he would go to bed, snatch an hour or two’s sleep, and be at it again until it was time to be off to the City. This was his routine, and Kate quickly planned how to take advantage of it.

Waiting till sister Fanny was asleep, she would slip out of bed, hurry into her clothes, all except her frock and shoes, and, covering them with her little nightgown, creep back into bed again. Thus prepared for eventualities, she would fall asleep. But not for long. Somehow she would manage to wake again in the small hours of the morning and see if the light of the gas jet in the passage still shone through the chink of the door. If it did, she would climb with all quietness out of bed, doff her nightdress, slip into her frock, take her shoes in her hand and creep softly down to the drawing-room, where her father was at work. Then he would fasten her dress and she would set to work to make his toast. And so th. e two would breakfast together alone in the early hours with supreme satisfaction.

More to come

…

KATE GREENAWAY.

At the age of 16.At the age of 21.

Miss Greenaway worked very hard at the production of the designs for birthday cards and valentines. They constantly improved in harmony of colour and delicacy of effect. A curious chance revealed to her the wonders of medieval illumination. Mr. Loftie was engaged at the time on a volume of topographical studies for the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, and wanted a copy from the pages of the book of Benefactors of St. Albans Abbey—Nero, D. 7, in the MS. room at the British Museum. Mr. Thompson, better known as Sir E. Maunde Thompson, Principal Librarian, was head of the department, and showed her many of the treasures in his charge, and he arranged her seat and gave her every possible assistance. She undertook to make a coloured drawing of Abbot John of Berkhampstead wringing his hands, for Mr. Loftie’s book. Being still in want of work, this particular job, with its collateral advantages in learning, pleased her very much. Another lady who was copying an illuminated border was her next neighbour at the same table, and they seem to have made one another’s acquaintance on the occasion. In after years Miss Greenaway quaintly said ‘this was the first duchess she had ever met’—the late Duchess of Cleveland, Lord Rosebery’s mother, who was a notable artist, and who died only a few months before Miss Greenaway herself. As for the Abbot, the committee of the S.P.C.K. rejected him, and the picture passed into and remained in Mr. Loftie’s possession. It figured later in his London Afternoons (p. 110), as Miss Greenaway only a few days before her death gave him leave to make what use of it he pleased.

Her first great success was a valentine. It was designed for Messrs. Marcus Ward, whose London manager hardly recognised, her introducer thought, what a prize they had found. The rough[48] proof of the drawing, in gold and colour, is both crude and inharmonious, but it has merits of delicacy and composition which account for the fact that the firm is said to have sold upwards of 25,000 copies of it in a few weeks. Her share of the profits was probably no more than £3. She painted many more on the same terms that year and the next, and was constantly improving in every way as she became better acquainted with her own powers and with the capabilities, at that time very slight, of printing in colour. ‘I have a beautiful design,’ says Mr. Loftie, ‘in the most delicate tints, for another valentine, which she brought me herself to show how much better she now understood harmony. It was unfinished, and in fact was never used by the firm. I need not go into the circumstances under which she severed her connection with them, but I well remember her remarkable good-temper and moderation. In the end it was for her benefit. Mr. Edmund Evans seized the chance, and eventually formed the partnership which subsisted for many years, till near the end of her life.’

About the year 1879 Mr. Loftie met her one day at a private view in Bond Street. She was always very humble about herself. She was the very last person to recognise her own eminence, and was always, to the very end, keen to find out if any one could teach her anything or give her a hint or a valuable criticism. She was also very shy in general society, and inclined to be silent and to keep in the background. On this occasion, however, she received him laughing heartily. ‘The lady who has just left me,’ she said, ‘has been staying in the country and has been to see her cousins. I asked if they were growing up as pretty as they promised. “Yes,” she replied, “but they spoil their good looks, you know, by dressing in that absurd Kate Greenaway style”—quite forgetting that she was talking to me!’ Kate would often repeat the story with much zest.

On two subsequent occasions did she execute work for books in which Mr. Loftie was concerned. In 1879 he asked her for some suggestions for illustrations of Mr. and Lady Pollock’s Amateur Theatricals in his ‘Art at Home’ Series (Macmillan & Co.). She sent him half-a-dozen lovely sketches, of which only three were accepted by the publishers. The frontispiece, ‘Comedy,’ a charming drawing, was not well engraved. A tail-piece on p. 17 shows a slight but most graceful figure of a young girl in the most characteristic ‘Kate Greenaway’ costume. The third, less characteristic, is even more charming—‘Going on.’ Among the sketches was a ‘Tragedy,’ represented by a youthful Hamlet in black velvet holding a large turnip apparently to represent the skull of Yorick. This was never completed.

THE ELF RING.

From a large water-colour drawing in the possession of John Greenaway, Esq.

In 1874 Kate Greenaway illustrated a little volume of fairy stories, issued in coloured boards by Griffith & Farran, entitled Fairy Gifts; or A Wallet of Wonders. It was written by Kathleen Knox, the author of Father Time’s Story-Book, and contained four full-page and seven small woodcuts, engraved by John Greenaway. The more important illustrations are prettily composed, while revealing a fine taste in witches and apparitions; and the small sketches are daintily touched in. It was Kate’s first appearance on any title-page. There was nothing remarkable in the little volume, yet it met with considerable popular favour. The first edition consisted of 2,000 copies; in 1880 it was reprinted to the extent of half as many. In 1882 a cheap edition of 5,000 copies was issued, and later in the year this large number was repeated. To what extent the artist shared in the success does not appear.

The year 1875, so far as earnings were concerned, was a lean year, and introduced the names of no new clients. This does not indicate that her activity was any the less than the year before. Indeed, we must remember that in the life of the artist results, so far as monetary reward is concerned, represent previous rather than contemporaneous activity, for payment is made certainly after the work is sold, and in the case of work for the press as often as not after publication. In the following year (1876) her earnings again ran into £200, her water-colour drawing at the Dudley being sold for twenty guineas, and her two black-and-white drawings for ten guineas the pair. But the crowning event of this year was the publication by Mr. Marcus Ward of the volume mentioned by Mr. Loftie, entitled ‘The Quiver of Love, a Collection of Valentines, Ancient and Modern, with Illustrations in Colours from Drawings by Walter Crane and K. Greenaway.’ All the designs had already been published separately. The verses were mainly from the pen of Mr. Loftie himself, although he is modest enough not to claim them in his notes…..

Book-plate designed for Miss Maud Locker-Lampson. …

Kate Greenaway was now in her thirty-third year, and, though fairly prosperous, could scarcely consider herself successful. Commissions were certainly coming in faster and faster, and in 1877, when she took her studio to College Place, Liverpool Road, Islington, her earnings had nearly reached £300; but she had not yet made any great individual mark. She appeared in the Royal Academy Exhibition and sold her picture ‘Musing’ for twenty guineas. She was a recognised contributor to the Dudley Gallery, and was pretty sure of buyers there. She was getting more or less regular employment on the Illustrated London News. She had been asked by Mr. W. L. Thomas of the newly established Graphic to provide him with a running pictorial full-page story after the manner of Caldecott, and had succeeded in satisfying his fastidious taste,[56] though the first sketch-plan which she sent seemed to him lacking in humour. ‘They strike me,’ he wrote, ‘as being a little solemn in tone.’ But this defect was soon rectified, and the result was so greatly admired that it led to many further commissions from the artist-editor.

These were gratifying and encouraging results, but in Kate’s opinion they were but the prizes of the successful artist-hack. Her name had not yet passed into the mouth of the town. Though she had drawn many charming pictures, she had not yet drawn the public.

What was true of the public was true of the publishers. Though Messrs. Marcus Ward of Belfast had seen the possibilities that lay in her designs for valentines, Christmas cards, and the like, and had achieved a real success by their publication, Kate was but yet only the power behind the throne. She was the hidden mainspring of a clock with the maker’s name upon the dial. Now all this was to be changed by a business arrangement, almost amounting to a partnership, in which she was to take her full share of the credit as well as of the spoil.

The story will be best told in the words of the man who so boldly backed his opinion as to print a first edition of 20,000 copies of a six-shilling book written and illustrated by a young lady who could hardly yet be said to have commanded anything like wide public approval. This was Mr. Edmund Evans.

Mr. Edmund Evans was primarily a colour-printer; his wood-engraving department was subsidiary. For the purposes of his business he owned a good many machines; he had three houses full of them in the City, and he was sometimes puzzled to find work to keep them going, to do which is at the root of commercial economy and success in his business. He printed most of the ‘yellow-backs’ of the time, covers for books as well as for small magazines of a semi-religious character, working-men’s magazines, and so forth, all with much colour-work in them. Mr. Evans also executed much high-class work of the kind, such as Doyle’s Chronicles of England, which had done much to make his reputation. Therefore, to fill up the spare time during which his machines would otherwise be idle, he began publishing the toy-books of Mr. Walter Crane, then those of Randolph Caldecott, and finally he turned his attention to Miss Kate Greenaway.

It should be recorded to the credit of Mr. Evans that he[57] excelled all others in the skill with which he produced his colour-effects with a small number of printings. Mr. John Greenaway, himself an expert in the preparation of blocks for colour-printing, as well as an artist of much intelligence, used to declare that no other firm in London could come near the result that Edmund Evans would get with as few, say, as three colour-blocks, so wonderful was his ingenuity, so great his artistic taste, and so accurate his eye.

Mr. Evans informs us:

I had known John Greenaway, father of K. G.,[12] since I was fourteen years of age. He was an assistant engraver to Ebenezer Landells,[13] to whom I was apprenticed. I knew he was having one of his daughters educated for the musical profession and another for drawing. I had only seen engravings made from drawings on wood by ‘K. G.’ for Cassell & Co., as well as some Christmas cards by Marcus Ward & Co. from water-colour drawings of very quaint little figures of children. Very beautiful they were, for they were beautifully lithographed.

About 1877-78 K. G. came to see us at Witley, bringing a collection of about fifty drawings she had made, with quaint verses written to them. I was fascinated with the originality of the drawings and the ideas of the verse, so I at once purchased them and determined to reproduce them in a little volume. The title Under the Window was selected afterwards from one of the first lines. At the suggestion of George Routledge & Sons I took the drawings and verses to Frederick Locker, the author of London Lyrics, to ‘look over’ the verses, not to rewrite them, but only to correct a few oddities which George Routledge & Sons did not quite like or understand. Locker was very much taken with the drawings and the verses, and showed them to Mrs. Locker with quite a gusto; he asked me many questions about her, and was evidently interested in what I told him of her. I do not think that he did anything to improve the verses, nor did K. G. herself.

Locker soon made her acquaintance and introduced her into some very good society. She often stayed with them at Rowfant, Sussex, and also at Cromer.

George Eliot was at the time staying at Witley. She called on us one day and saw the drawings and was much charmed with them. A little time afterwards I wrote to George Eliot to ask if she would write me a short story of, or about, children suitable for K. G. to illustrate. Her reason for refusing was interesting:—

‘The Heights, Witley,

October 22, 1879.

‘Dear Mr. Evans—It is not my way to write anything except from my own inward prompting. Your proposal does me honour, and I should feel much trust in the charming pencil of Miss Greenaway, but I could never say “I will write this or that” until I had myself felt the need to do it….—Believe me, dear Mr. Evans, yours most sincerely,

M. E. Lewes.’

After I had engraved the blocks and colour-blocks, I printed the first edition of 20,000 copies, and was ridiculed by the publishers for risking such a large edition of a six-shilling book; but the edition sold before I could reprint another edition; in the meantime copies were sold at a premium. Reprinting kept on till 70,000 was reached.[14]

I volunteered to give K. G. one-third of the profit of this book. It was published in the autumn of 1879. We decided to publish The Birthday Book for Children in 1880. Miss Greenaway considered that she should have half the profits of all books we might do together in future, and that I should return to her the original drawings after I had paid her for them and reproduced them. To both these terms I willingly agreed.[15] … Then came the Birthday Book, Mother Goose, and part of A Day in a Child’s Life, in 1881; Little Ann, 1883; the Language of Flowers, Kate Greenaway’s Painting-Book, and Mavor’s Spelling-Book, 1884-85; Marigold Garden and A Apple Pie, 1886; The Queen of The Pirate Isle and The Pied Piper of Hamelin, 1887; The Book of Games, 1888; King Pepito, 1889. Besides the above and a certain number of smaller issues, minor works, and detached designs, the artist was responsible for an Almanack from 1883 to 1897, with the sole exception of the year 1896.

The books named above are those which we did together.

There is a little story my daughter Lily tells of her tenderness towards animals. She was walking one day and came upon a stream with a rat sitting on a stone. Lily wished to startle it, and was about to throw a stone in the water, but K. G. exclaimed—‘Oh, don’t, Lily, perhaps it’s ill!’ We all loved her

THE LITTLE MODEL.

From a water-colour drawing in the possession of Mrs. F. St. G. Whitly.

.

‘MARY HAD A LITTLE LAMB.’

From a water-colour drawing in the possession of Mrs. Arthur Severn. … . …

. …

CHAPTER VI

1879-1880

CHRISTMAS CARDS AND BOOKS—H. STACY MARKS, R.A., JOHN RUSKIN, AND FREDERICK LOCKER-LAMPSON

The year 1846—the birth-year of both Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott—marked also the genesis of the Christmas card. What was in the first instance a pretty thought and dainty whim, by its twenty-fifth year had become a craze, and has now, another quarter of a century later, fallen into a tenacious and somewhat erratic dotage. The first example of which there is any trace was a private card designed by J. C. Horsley, R.A., for Sir Henry Cole, of the South Kensington Museum, and it proved to be the forerunner of at least two hundred thousand others that were placed upon the market before 1894 in England alone. For five-and-twenty years the designing of them was practically confined to the journeyman artist, who rang the changes on the Christmas Plum-pudding, the Holly and Mistletoe, and on occasional religious reference, with little originality and less art. Later on all that was changed. About 1878 certain manufacturers, printers, and publishers recognised the possibilities which lay in an improved type of production, with the result that in 1882 so great was the boom that ‘one firm alone paid in a single year no less a sum than seven thousand pounds for original drawings’ for these cards.[19]