For years, I have wanted to look out my glass doors during the winter and early spring and see the seasons change from inside my home, This year, as I prepare for Advent, I have planted some things that will eventually shriek against the wintry sky,

Advent is celebrated before Christmas, and I have decided to focus on red for my December Garden.

Winter Red

Image Credit: American Meadows

Size 6′ – 8′ x 6′ -8′

We don’t get much snow in Mississippi, but we have a lot of gray skies. The red berries on this plant are still a winter treat against a gray sky.

Winter Red

Winter Red

Image Credit: American Meadows

“Winter Red Winterberry is famed for its signature clusters of festive red berries that persist into winter, providing year-round color and food for birds. This female plant’s small white flowers require pollination from male Southern Gentleman Winterberry plants to produce berries. Plant at least one male for up to 6-10 female plants. In autumn, this native shrub’s glossy green foliage will drop, leaving the stunning berry-studded branches. (Ilex verticillata)” I planted Southern Gentleman for my Winter Reds.

Winter Red

Image Credit: American Meadows

Winter Red [Leaves in Fall}

Image Credit: American Meadows

I have planted a Yuletide Camellia slightly behind and between each of the Winter Redsl

Yuletide Camellia – Image Credit The Sill

Height 8′ – 10′

Yuletide is a perfect name for this plant which has bright red flowers that rest in pools of deep waxy green leaves. It looks like Christmas,

The Color Red is A Color of Hope

Farmhouse in WinterOil Painting on Hardboard Panel 9″ x 12″

February 11, 2023

On the first day of Advent, I light a candle to signify Hope. Red is a Hopeful Color.

All the plants I have previously named are at the back of my Hope Garden. But I’ll add other colors to my Hope Garden. Those colors will reflect the colors of Easter and Spring:

“Can we not trace the sign of the Cross in the first hint of the new spring’s dawning? In many cases, as in the chestnut, before a single old leaf has faded, next year’s buds may be seen, at the summit of branch and twig, formed into its very likeness: in others the leaf-buds seem to bear its mark by breaking through the stem blood-red. Back in the plant’s first stages, the crimson touch is to be found in seed-leaves and fresh shoots, and even in the hidden sprouts. Look at the acorn, for instance, as it breaks its shell, and see how the baby tree bears its birthmark: it is the blood-red in which the prism ray dawns out of the darkness, and the sunrise out of the night. The very stars, science now tells us, glow with this same colour as they are born into the universe out of the dying of former stars.”

I. Lillias Trotter. Parable of the Cross.

I am pointing this out to support my thesis that Advent does not end with the celebration of Christ’s birth.

The Greatest Hope of Advent Is That Christ Will Come Again.

Christ has died.

Christ is risen.

Christ will come again. – The Holy Eucharist Rite II

I celebrate the Christmas part of Avent with Red Colors in my garden,

I celebrate the resurrection part of Advent with the pastel colors that I associate with Easter:

An iron obelisk sits in front of the red shrubs I’ve named above. In that obelisk, I have planted a gorgeous pink rose that will bloom soon after Easter:

Iron Obelisk in Jacki Kellum’s Garden – 2021 – Zéphirine Drouhin Rose

Zéphirine Drouhin Rose

For this year’s Hope Garden, I have planted a Zéphirine Drouhin Rose inside the obelisk, centered in front of the shrubs

Jacki Kellum Garden in the Ozarks Mountains

Zéphirine Drouhin Rose

Image Credit: Heirloom Roses

1868

If Zéphirine Drouhin Rose were only a bit more fragrant, it would be a nearly perfect rose. She has no thorns, and I plant Zeph in places where I know that thorns would be hazardous. She only blooms once during the spring, and that is another drawback to this rose, but in spite of these things, Zéphirine Drouhin is one of my Queen Roses. I plant her in several places around my gardens.

. I am primarily planting perennials around and in front of this obelisk–many of them are Native Perennials.

Perennial Garden Plants Are the Essence of Hope

Annual Plants only perform in the garden for one season.

Perennial Plants perform in the garden year after year.

Following, I’ll show you what I hope will grow in my garden, according to the months I expect them to perform:

January

American Witch Hazel

Winterberry Holly

American Witch Hazel

American Witch Hazel – Image Credit Wikimedia

American Witch Hazel – Image Credit Flickr

February

American Witch Hazel

Virginia Spring Beauty

Virginia Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica)

Image Credit: Native Wildflowers Nursery

Height: 6″ – 10″

Spring Beauties are Ephemerals. “A spring ephemeral is a native plant that blooms in early spring and only lasts a short amount of time. They are woodland wildflowers that emerge, then quickly go dormant.” Google ai

First Blossom Noticed in May Garden

February 16, 2024

According to a wise person in my garden group, the first leaves or the spring beauty were purple because: “The purple color comes from anthocyanins, plant pigments that are usually produced in winter.” Nate Venarske

Mining Bee Gathering Pollen from Spring Beauty Flowers

Image Credit: Flickr

Mining Bees depend on the pollen from Spring Beauties. We must preserve all our native plants–even the tiny ones. Each plant is an important part of our region’s biodiversity.

“…mining bees do not produce honey. Mining bees are solitary bees that create nests in the ground. They are important pollinators for many types of flowers.” Google ai

Early spring is fairly cold and damp where I live, and my garden will begin to bud and bloom while I am still sipping hot tea inside. I am adding two more forsythia shrubs to watch bloom from inside my house:

Forsythia Lynwood Gold

Image Credit: Planting Tree

Size: 6′ – 10′

I’m not sure when I will notice forsythia buds in a normal Mississippi year. Yesterday, on November 19, 2024, one of my forsythias bloomed, but that was abnormal. I expect the forsythias to bloom in February. The spring bulbs will bloom soon thereafter.

Tazetta Daffodils

Image Credit: Wikipedia

“The Daffodil is the Lent Lily. Mingled with Yew, which is the emblem of the Resurrection, it forms an appropriate decoration for Easter. Lent Lilies are called by the French Pauvres Filles de Ste. Clare.” Folkard, Richard. Plant Lore.

Crocus

Holland Bulb Compa

May Perennial Plant Natives in Mississippi

Blue False Indigo

Golden Alexanders

Milkweed

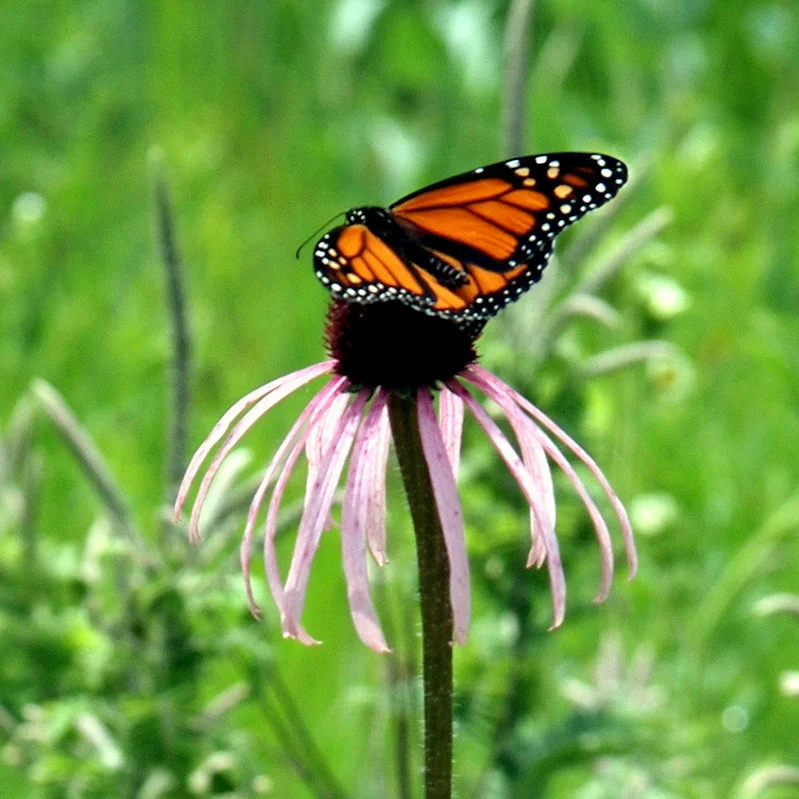

Purple Coneflower

Red Columbine

Woodland Phlox

Iris Pallida

image Credit: Wikipedia

Iris Pallida is a very old species of iris plants.

|

|

Iris Albicans

Image Credit: Iris Encyclopedia

Cracker Jack or African Marigolds April 27, 2024

May Perennial Plant Natives in Mississippi

Blue False Indigo

Golden Alexanders

Milkweed

Purple Coneflower

Red Columbine

Woodland Phlox

Jacob Cline Bee Balm

Jacki Kellum Garden May 30, 2023

June Perennial Native Plants in Mississippi

Blue False Indigo

Golden Alexanders

Milkweed

Purple Coneflower

Red Columbine

July Perennial Native Plants in Mississippi

Golden Alexander

Milkweed

Purple Coneflower

Swamp Rose Mallow

Western Ironweed

Pale Purple Coneflower

Image Credit:American Meadows

August Perennial Native Plants in Mississippi

Black-Eyed Susan

Milkweed

New England Aster

Purple Coneflower

Swamp Rose Mallow

Western Ironweed

September Perennial Native Plants in Mississippi

Black-Eyed Susan

Milkweed

New England Aster

Stiff-Leaved Goldenrod

Swamp Rose Mallow

Western Ironweed

October Perennial Native Plants in Mississippi

Black-Eyed Susan

New England Aster

Stiff-Leaved Goldenrod \

\

Hardy Chrysanthemums Jacki Kellum Garden October 14, 2024

Saffron

Image Credit: CZ Grain Company [ Saffron is a crocus that blooms during October.}

November Perennial Native Plants in Mississippi

Little Bluestem

Muhly Grass

Winterberry Holly

Morning Glories November 7, 2014 Jacki Kellum Garden

December Perennial Native Plants in Mississippi

Muhly Grass

Winterberry Holly

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.