SUN-WORSHIP.

THE SOURCES OF HALLOWE’EN

“If we could ask one of the old-world pagans whom he revered as his greatest gods, he would be sure to name among them the sun-god; calling him Apollo if he were a Greek; if an Egyptian, Horus or Osiris; if of Norway, Sol; if of Peru, Bochica. As the sun is the center of the physical universe, so all primitive peoples made it the hub about which their religion revolved, nearly always believing it a living person to whom they could say prayers and offer sacrifices, who directed their lives and destinies, and could even snatch men from earthly existence to dwell for a time with him, as it draws the[Pg 2] water from lakes and seas.

“In believing this they followed an instinct of all early peoples, a desire to make persons of the great powers of nature, such as the world of growing things, mountains and water, the sun, moon, and stars; and a wish for these gods they had made to take an interest in and be part of their daily life. The next step was making stories about them to account for what was seen; so arose myths and legends.

“The sun has always marked out work-time and rest, divided the year into winter idleness, seed-time, growth, and harvest; it has always been responsible for all the beauty and goodness of the earth; it is itself splendid to look upon. It goes away and stays longer and longer, leaving the land in cold and gloom; it returns bringing the long fair days and resurrection of spring. A Japanese legend tells how the hidden sun was lured out by an image made of a copper plate with saplings radiating from it like sunbeams, and a fire kindled, dancing, and prayers; and[Pg 3] round the earth in North America the Cherokees believed they brought the sun back upon its northward path by the same means of rousing its curiosity, so that it would come out to see its counterpart and find out what was going on.

Ancient Pagan Holidays Celebrated Today–Some of Them Are Celebrated as Christian

“All the more important church festivals are survivals of old rites to the sun. “How many times the Church has decanted the new wine of Christianity into the old bottles of heathendom.”

“Yule-tide, the pagan Christmas, celebrated the sun’s turning north,

“and the old midsummer holiday is still kept in Ireland and on the Continent as St. John’s Day by the lighting of bonfires and a dance about them from east to west as the sun appears to move.

“The pagan Hallowe’en at the end of summer was a time of grief for the decline of the sun’s glory, as well as a harvest festival of thanksgiving to him for having ripened the grain and fruit, as we formerly had husking-bees when the ears had been garnered, and now keep our own Thanksgiving by eating of our winter store in praise of[Pg 4] God who gives us our increase.” Kelley, The Book of Hallowe’en,

Pomona – Goddess of Fruit Trees

.

Pomona, by Nicolas Fouché,

“Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit, lends us the harvest element of Hallowe’en;

[The Greek goddess Demeter is related to Cropss & Harvest.]

“Pomona was the goddess of fruit trees, gardens, and orchards. Unlike many other Roman goddesses and gods, she does not have a Greek counterpart, though she is commonly associated with Demeter. She watches over and protects fruit trees and cares for their cultivation. She was not actually associated with the harvest of fruits itself, but with the flourishing of the fruit trees. In artistic depictions she is generally shown with a platter of fruit or a cornucopia.” Wikipedia

“the Celtic day of “summer’s end” was a time when spirits, mostly evil, were abroad; the gods whom Christ dethroned joined the ill-omened throng; the Church festivals of All Saints’ and All Souls’ coming at the same time of year—the first of November—contributed the idea of the return of the dead; and the Teutonic May Eve assemblage of witches brought its hags and their attendant beasts to help celebrate the night of October 31st.

THE CELTS: THEIR RELIGION AND FESTIVALS

“The first reference to Great Britain in European annals of which we know was the statement in the fifth century b. c. of the Greek historian Herodotus, that Phœnician sailors went to the British Isles for tin. He called them the “Tin Islands.” The people with whom these sailors traded must have been Celts, for they were the first inhabitants of Britain who worked in metal instead of stone.

“The Druids were priests of the Celts centuries before Christ came. There is a tradition in Ireland that they first arrived there in 270 b. c., seven hundred years before St. Patrick. The account of them written by Julius Cæsar half a century before Christ speaks mainly of the Celts of Gaul, dividing them into two ruling classes who kept the people almost in a state of slavery; the[Pg 6] knights, who waged war, and the Druids who had charge of worship and sacrifices, and were in addition physicians, historians, teachers, scientists, and judges.

“Cæsar says that this cult originated in Britain, and was transferred to Gaul. Gaul and Britain had one religion and one language, and might even have one king, so that what Cæsar wrote of Gallic Druids must have been true of British.

“The Celts worshipped spirits of forest and stream, and feared the powers of evil, as did the Greeks and all other early races. Very much of their primitive belief has been kept, so that to Scotch, Irish, and Welsh peasantry brooks, hills, dales, and rocks abound in tiny supernatural beings, who may work them good or evil, lead them astray by flickering lights, or charm them into seven years’ servitude unless they are bribed to show favor.

“The name “Druid” is derived from the Celtic word “druidh,” meaning “sage,” connected with the Greek word for oak, “drus,”

Taliesin: Battle of the Trees.

“for the oak was held sacred by them as a symbol of the omnipotent god, upon whom they depended for life like the mistletoe growing upon it. Their ceremonies were held in oak-groves.

“Later from their name a word meaning “magician” was formed, showing that these priests had gained the reputation of being dealers in magic.

“The Druid followed him and suddenly, as we are told, struck him with a druidic wand, or according to one version, flung at him a tuft of grass over which he had pronounced a druidical incantation.” O’Curry: Ancient Irish.

“They dealt in symbols, common objects to which was given by the interposition of spirits, meaning to signify certain facts, and[Pg 8] power to produce certain effects. Since they were tree-worshippers, trees and plants were thought to have peculiar powers.

“Cæsar provides them with a galaxy of Roman divinities, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, and Minerva, who of course were worshipped under their native names. Their chief god was Baal, of whom they believed the sun the visible emblem. They represented him by lowlier tokens, such as circles and wheels. The trefoil, changed into a figure composed of three winged feet radiating from a center, represented the swiftness of the sun’s journey. The cross too was a symbol of the sun, being the appearance of its light shining upon dew or stream, making to the half-closed eye little bright crosses. One form of the cross was the swastika.

“To Baal they made sacrifices of criminals or prisoners of war, often burning them alive in wicker images. These bonfires lighted on the hills were meant to urge the god to protect and bless the crops and herds.

“From the appearance of the victims sacrificed in[Pg 9] them, omens were taken that foretold the future. The gods and other supernatural powers in answer to prayer were thought to signify their will by omens, and also by the following methods: the ordeal, in which the innocence or guilt of a person was shown by the way the god permitted him to endure fire or other torture; exorcism, the driving out of demons by saying mysterious words or names over them. Becoming skilled in interpreting the will of the gods, the Druids came to be known as prophets.

Todhunter: Druid song of Cathvah.

“They kept their lore for the most part a secret, forbidding it to be written, passing it down by word of mouth. They taught the[Pg 10] immortality of the soul, that it passed from one body to another at death.

Drayton: Polyolbion.

“They believed that on the last night of the old year (October 31st) the lord of death gathered together the souls of all those who had died in the passing year and had been condemned to live in the bodies of animals, to decree what forms they should inhabit for the next twelve months. He could be coaxed to give lighter sentences by gifts and prayers.

“The badge of the initiated Druid was a glass ball reported to be made in summer of the spittle of snakes, and caught by the priests as the snakes tossed it into the air.

Mason: Caractacus.

“It was real glass, blown by the Druids themselves. It was supposed to aid the wearer in winning lawsuits and securing the favor of kings.

An animal sacred to the Druids was the cat.

“A slender black cat reclining on a chain of old silver” guarded treasure in the old days. For a long time cats were dreaded by the people because they thought human beings had been changed to that form by evil means.

“The chief festivals of the Druids fell on four days, celebrating phases of the sun’s career. Fires of sacrifice were lighted especially at spring and midsummer holidays, by exception on November 1st.

“May Day and November Day were the more important, the beginning and end of summer, yet neither equinoxes nor solstices. The time was divided then not according to[Pg 12] sowing and reaping, but by the older method of reckoning from when the herds were turned out to pasture in the spring and brought into the fold again at the approach of winter—by a pastoral rather than an agricultural people.

“On the night before Beltaine (“Baal-fire”), the first of May, fires were burned to Baal to celebrate the return of the sun bringing summer. Before sunrise the houses were decked with garlands to gladden the sun when he appeared; a rite which has survived in “going maying.” The May-Day fires were used for purification. Cattle were singed by being led near the flames, and sometimes bled that their blood might be offered as a sacrifice for a prosperous season.

Kickham: St. John’s Eve.

A cake was baked in the fire with one piece[Pg 13] blacked with charcoal. Whoever got the black piece was thereby marked for sacrifice to Baal, so that, as the ship proceeded in safety after Jonah was cast overboard, the affairs of the group about the May-Eve fire might prosper when it was purged of the one whom Baal designated by lot. Later only the symbol of offering was used, the victim being forced to leap thrice over the flames.

“In history it was the day of the coming of good. Partholon, the discoverer and promoter of Ireland, came thither from the other world to stay three hundred years. The gods themselves, the deliverers of Ireland, first arrived there “through the air” on May Day.

“June 21st, the day of the summer solstice, the height of the sun’s power, was marked by midnight fires of joy and by dances. These were believed to strengthen the sun’s heat. A blazing wheel to represent the sun was rolled down hill.

Hauptmann: Sunken Bell.

(Lewisohn trans.)

“Spirits were believed to be abroad, and torches were carried about the fields to protect them from invasion. Charms were tried on that night with seeds of fern and hemp, and dreams were believed to be prophetic.

“Lugh, in old Highland speech “the summer sun”

had for father one of the gods and for mother the daughter of a chief of the enemy. Hence he possessed some good and some evil tendencies.[Pg 15] He may be the Celtic Mercury, for they were alike skilled in magic and alchemy, in deception, successful in combats with demons, the bringers of new strength and cleansing to the nation. He said farewell to power on the first of August, and his foster-mother had died on that day, so then it was he set his feast-day. The occasion was called “Lugnasad,” “the bridal of Lugh” and the earth, whence the harvest should spring. It was celebrated by the offering of the first fruits of harvest, and by races and athletic sports. In Meath, Ireland, this continued down into the nineteenth century, with dancing and horse-racing the first week of August.

POMONA

“Ops was the Latin goddess of plenty. Single parts of her province were taken over by various other divinities, among whom was Pomona (pomorum patrona, “she who cares for fruits”). She is represented as a maiden with fruit in her arms and a pruning-knife in her hand.

“I am the ancient apple-queen.As once I was so am I now—For evermore a hope unseenBetwixt the blossom and the bough.

Morris: Pomona.

“Many Roman poets told stories about her, the best known being by Ovid, who says that she[Pg 24] was wooed by many orchard-gods, but preferred to remain unmarried. Among her suitors was Vertumnus (“the changer”), the god of the turning year, who had charge of the exchange of trade, the turning of river channels, and chiefly of the change in nature from flower to ripe fruit. True to his character he took many forms to gain Pomona’s love. Now he was a ploughman (spring), now a fisherman (summer), now a reaper (autumn).

“At last he took the likeness of an old woman (winter), and went to gossip with Pomona. After sounding her mind and finding her averse to marriage, the woman pleaded for Vertumnus’s success.

“Is not he the first to have the fruits which are thy delight? And does he not hold thy gifts in his joyous right hand?”

Ovid: Vertumnus and Pomona.

“Then the crone told her the story of Anaxarete who was so cold to her lover Iphis that he hanged himself, and she at the window[Pg 25] watching his funeral train pass by was changed to a marble statue. Advising Pomona to avoid such a fate, Vertumnus donned his proper form, that of a handsome young man, and Pomona, moved by the story and his beauty, yielded and became his wife.

“Vertumnus had a statue in the Tuscan Way in Rome, and a temple. His festival, the Vortumnalia, was held on the 23d of August, when the summer began to wane. Garlands and garden produce were offered to him.

“Pomona had been assigned one of the fifteen flamina, priests whose duty it was to kindle the fire for special sacrifices. She had a grove near Ostia where a harvest festival was held about November first. Not much is known of the ceremonies, but from the similar August holiday much may be deduced.

“Then the deities of fire and water were propitiated that their disfavor might not ruin the crops. On Pomona’s day doubtless thanks was rendered them for their aid to the harvest. An offering of first-fruits was made in August; in November the winter[Pg 26] store of nuts and apples was opened. The horses released from toil contended in races.

“From Pomona’s festival nuts and apples, from the Druidic Samhain the supernatural element, combined to give later generations the charms and omens from nuts and apples which are made trial of at Hallowe’en.” Kelley, The Book of Hallowe’en,

THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY.|

ALL SAINTS’. ALL SOULS’

The great power which the Druids exercised over their people interfered with the Roman rule of Britain. Converts were being made at Rome. Augustus forbade Romans to became initiated, Tiberius banished the priestly clan and their adherents from Gaul, and Claudius utterly stamped out the belief there, and put to death a Roman knight for wearing the serpent’s-egg badge to win a lawsuit. Forbidden to practise their rites in Britain, the Druids fled to the isle of Mona, near the coast of Wales. The Romans pursued them, and in 61 a. d. they were slaughtered and their oak groves cut down. During the next three centuries the cult was stifled to death, and the Christian religion substituted.

It was believed that at Christ’s advent the pagan gods either died or were banished.

Milton: On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity.

The Christian Fathers explained all oracles and omens by saying that there was something in them, but that they were the work of the evil one. The miraculous power they seemed to possess worked “black magic.”

It was a long, hard effort to make men see that their gods had all the time been wrong, and harder still to root out the age-long growth of rite and symbol. But on the old religion might be grafted new names; Midsummer was dedicated to the birth of Saint John; Lugnasad became Lammas. The fires belonging to these times of year were retained, their old significance forgotten or reconsecrated. The rowan, or mountain ash, whose[Pg 29] berries had been the food of the Tuatha, now exorcised those very beings. The trefoil signified the Trinity, and the cross no longer the rays of the sun on water, but the cross of Calvary. The fires which had been built to propitiate the god and consume his sacrifices to induce him to protect them were now lighted to protect the people from the same god, declared to be an evil mischief-maker. In time the autumn festival of the Druids became the vigil of All Hallows or All Saints’ Day.

All Saints’ was first suggested in the fourth century, when the Christians were no longer persecuted, in memory of all the saints, since there were too many for each to have a special day on the church calendar. A day in May was chosen by Pope Boniface IV in 610 for consecrating the Pantheon, the old Roman temple of all the gods, to the Virgin and all the saints and martyrs. Pope Gregory III dedicated a chapel in St. Peter’s to the same, and that day was made compulsory in 835 by Pope Gregory IV, as All[Pg 30] Saints’. The day was changed from May to November so that the crowds that thronged to Rome for the services might be fed from the harvest bounty. It is celebrated with a special service in the Greek and Roman churches and by Episcopalians.

In the tenth century St. Odilo, Bishop of Cluny, instituted a day of prayer and special masses for the souls of the dead. He had been told that a hermit dwelling near a cave

“heard the voices and howlings of devils, which complained strongly because that the souls of them that were dead were taken away from their hands by alms and by prayers.”

De Voragine: Golden Legend.

This day became All Souls’, and was set for November 2d.

It is very appropriate that the Celtic festival when the spirits of the dead and the supernatural powers held a carnival of triumph over the god of light, should be followed by All Saints’ and All Souls’. The church holy-days were celebrated by bonfires to light souls[Pg 31] through Purgatory to Paradise, as they had lighted the sun to his death on Samhain. On both occasions there were prayers: the pagan petitions to the lord of death for a pleasant dwelling-place for the souls of departed friends; and the Christian for their speedy deliverance from torture. They have in common the celebrating of death: the one, of the sun; the other, of mortals: of harvest: the one, of crops; the other, of sacred memories. They are kept by revelry and joy: first, to cheer men and make them forget the malign influences abroad; second, because as the saints in heaven rejoice over one repentant sinner, we should rejoice over those who, after struggles and sufferings past, have entered into everlasting glory.

Marks: All Souls’ Eve.

ORIGIN AND CHARACTER OF HALLOWE’EN OMENS

The custom of making tests to learn the future comes from the old system of augury from sacrifice. Who sees in the nuts thrown into the fire, turning in the heat, blazing and growing black, the writhing victim of an old-time sacrifice to an idol?

Many superstitions and charms were believed to be active at any time, but all those and numerous special ones worked best on November Eve. All the tests of all the Celtic festivals have been allotted to Hallowe’en. Cakes from the May Eve fire, hemp-seed and prophetic dreams from Midsummer, games and sports from Lugnasad have survived in varied forms.

Tests are very often tried blindfold, so that the seeker may be guided by fate. Many are mystic—to evoke apparitions from the past or[Pg 34] future. Others are tried with harvest grains and fruits. Because skill and undivided attention is needed to carry them through successfully, many have degenerated into mere contests of skill, have lost their meaning, and become rough games.

Answers are sought to questions about one’s future career; chiefly to: when and whom shall I marry? what will be my profession and degree of wealth, and when shall I die?

Hallowe’en Time.

HALLOWE’EN BELIEFS AND CUSTOMS IN IRELAND

“Ireland has a literature of Hallowe’en, or “Samhain,” as it used to be called. Most of it was written between the seventh and the twelfth centuries, but the events were thought to have happened while paganism still ruled in Ireland.

“The evil powers that came out at Samhain lived the rest of the time in the cave of Cruachan in Connaught, the province which was given to the wicked Fomor after the battle of Moytura. This cave was called the “hell-gate of Ireland,” and was unlocked on November Eve to let out spirits and copper-colored birds which killed the farm animals.

“They also stole babies, leaving in their place changelings, goblins who were old in wickedness while still in the cradle, possessing superhuman cunning and skill in music.

“One way of getting rid of these demon children was to ill-treat them so that their people[Pg 36] would come for them, bringing the right ones back; or one might boil egg-shells in the sight of the changeling, who would declare his demon nature by saying that in his centuries of life he had never seen such a thing before.

“Brides too were stolen.

Yeats: Land of Heart’s Desire.

In the first century b. c. lived Ailill and his queen Medb. As they were celebrating their Samhain feast in the palace,

O’Ciarain: Loch Garman.

they offered a reward to the man who should[Pg 37] tie a bundle of twigs about the feet of a criminal who had been hanged by the gate. It was dangerous to go near dead bodies on November Eve, but a bold young man named Nera dared it, and tied the twigs successfully. As he turned to go he saw

“the whole of the palace as if on fire before him, and the heads of the people of it lying on the ground, and then he thought he saw an army going into the hill of Cruachan, and he followed after the army.” Gregory: Cuchulain of Muirthemne.

“The door was shut. Nera was married to a fairy woman, who betrayed her kindred by sending Nera to warn King Ailill of the intended attack upon his palace the next November Eve.

“Nera bore summer fruits with him to prove that he had been in the fairy sid. The next November Eve, when the doors were opened Ailill entered and discovered the crown, emblem of power, took it away, and plundered the treasury. Nera never returned again to the homes of men.

“Another story of about the same time was[Pg 38] that of Angus, the son of a Tuatha god, to whom in a dream a beautiful maiden appeared. He wasted away with love for her, and searched the country for a girl who should look like her. At last he saw in a meadow among a hundred and fifty maidens, each with a chain of silver about her neck, one who was like the beauty of his dream. She wore a golden chain about her throat, and was the daughter of King Ethal Anbual. King Ethal’s palace was stormed by Ailill, and he was forced to give up his daughter. He gave as a reason for withholding his consent so long, that on Samhain Princess Caer changed from a maiden to a swan, and back again the next year.

“And when the time came Angus went to the loch, and he saw the three times fifty white birds there with their silver chains about their necks, and Angus stood in a man’s shape at the edge of the loch, and he called to the girl: ‘Come and speak with me, O Caer!’

“‘Who is calling me?’ said Caer.

“‘Angus calls you,’ he said, ‘and if you do[Pg 39] come, I swear by my word I will not hinder you from going into the loch again.'” Gregory: Cuchulain of Muirthemne.

“She came, and he changed to a swan likewise, and they flew away to King Dagda’s palace, where every one who heard their sweet singing was charmed into a sleep of three days and three nights.

“Princess Etain, of the race of the Tuatha, and wife of Midir, was born again as the daughter of Queen Medb, the wife of Ailill. She remembers a little of the land from which she came, is never quite happy,

By dusk or moonset have you never heard

Sweet voices, delicate music? Never seen

The passage of the lordly beautiful ones

Men call the Shee?”

Sharp: Immortal Hour.

even when she wins the love of King Eochaidh. When they have been married a year, there comes Midir from the Land of Youth.[Pg 40] By winning a game of chess from the King, he gets anything he may ask, and prays to see the Queen. When he sees her he sings a song of longing to her, and Eochaidh is troubled because it is Samhain, and he knows the great power the hosts of the air “have then over those who wish for happiness.”

for in no Gaelic lands

Is speech like this upon the lips of men.

No word of all these honey-dripping words

Is known to me.

Beware, beware the words

Brewed in the moonshine under ancient oaks

White with pale banners of the mistletoe

Twined round them in their slow and stately death.

It is the feast of Sáveen” (Samhain).

Sharp: Immortal Hour.

In vain Eochaidh pleads with her to stay with him. She has already forgotten all but Midir and the life so long ago in the Land of Youth.

Sharp: Immortal Hour.

She and Midir fly away in the form of two swans, linked by a chain of gold.

Cuchulain, hopelessly sick of a strange illness brought on by Fand and Liban, fairy sisters, was visited the day before Samhain by a messenger, who promised to cure him if he would go to the Otherworld. Cuchulain[Pg 42] could not make up his mind to go, but sent Laeg, his charioteer. Such glorious reports did Laeg bring back from the Otherworld,

Cuchulain’s Sick-bed. (Meyer trans.)

that Cuchulain went thither, and championed the people there against their enemies. He stayed a month with the fairy Fand. Emer, his wife at home, was beset with jealousy, and plotted against Fand, who had followed her hero home. Fand in fear returned to her deserted husband, Emer was given a Druidic drink to drown her jealousy, and Cuchulain another to forget his infatuation, and they lived happily afterward.

Even after Christianity was made the vital religion in Ireland, it was believed that places not exorcised by prayers and by the sign of the cross, were still haunted by Druids. As late as the fifth century the Druids kept[Pg 43] their skill in fortune-telling. King Dathi got a Druid to foretell what would happen to him from one Hallowe’en to the next, and the prophecy came true. Their religion was now declared evil, and all evil or at any rate suspicious beings were assigned to them or to the devil as followers.

Yeats: Land of Heart’s Desire.

The power of fairy music was so great that St. Patrick himself was put to sleep by a minstrel who appeared to him on the day before Samhain. The Tuatha De Danann, angered at the renegade people who no longer did them honor, sent another minstrel, who after laying the ancient religious seat Tara under a twenty-three years’ charm, burned[Pg 44] up the city with his fiery breath.

These infamous spirits dwelt in grassy mounds, called “forts,” which were the entrances to underground palaces full of treasure, where was always music and dancing. These treasure-houses were open only on November Eve

Expedition of Nera. (Meyer trans.)

when the throngs of spirits, fairies, and goblins trooped out for revels about the country. The old Druid idea of obsession, the besieging of a person by an evil spirit, was practised by them at that time.

Warren: Twig of Thorn.

If the fairies wished to seize a mortal—which power they had as the sun-god could take men to himself—they caused him to give them certain tokens by which he delivered[Pg 45] himself into their hands. They might be milk and fire—

Yeats: Land of Heart’s Desire.

or one might receive a fairy thorn such as Oonah brings home, which shrivels up at the touch of St. Bridget’s image;

“Oh, ever since I kept the twig of thorn and hid it, I have seen strange things, and heard strange laughter and far voices calling.”

Warren: Twig of Thorn.

or one might be lured by music as he stopped near the fort to watch the dancing, for the revels were held in secret, as those of the Druids had been, and no one could look on them unaffected.

A story is told of Paddy More, a great stout[Pg 46] uncivil churl, and Paddy Beg, a cheerful little hunchback. The latter, seeing lights and hearing music, paused by a mound, and was invited in. Urged to tell stories, he complied; he danced as spryly as he could for his deformity; he sang, and made himself so agreeable that the fairies decided to take the hump off his back, and send him home a straight manly fellow. The next Hallowe’en who should come by the same place but Paddy More, and he stopped likewise to spy at the merrymaking. He too was called in, but would not dance politely, added no stories nor songs. The fairies clapped Paddy Beg’s hump on his back, and dismissed him under a double burden of discomfort.

A lad called Guleesh, listening outside a fort on Hallowe’en heard the spirits speaking of the fatal illness of his betrothed, the daughter of the King of France. They said that if Guleesh but knew it, he might boil an herb that grew by his door and give it to the princess and make her well. Joyfully Guleesh hastened home, prepared the herb,[Pg 47] and cured the royal girl.

Sometimes people did not have the luck to return, but were led away to a realm of perpetual youth and music.

Yeats: Land of Heart’s Desire.

If one returned, he found that the space which seemed to him but one night, had been many years, and with the touch of earthly sod the age he had postponed suddenly weighed him down. Ossian, released from fairyland after three hundred years dalliance there, rode back to his own country on horseback. He saw men imprisoned under a block[Pg 48] of marble and others trying to lift the stone. As he leaned over to aid them the girth broke. With the touch of earth “straightway the white horse fled away on his way home, and Ossian became aged, decrepit, and blind.”

No place as much as Ireland has kept the belief in all sorts of supernatural spirits abroad among its people. From the time when on the hill of Ward, near Tara, in pre-Christian days, the sacrifices were burned and the Tuatha were thought to appear on Samhain, to as late as 1910, testimony to actual appearances of the “little people” is to be found.

“‘Among the usually invisible races which I have seen in Ireland, I distinguish five classes. There are the Gnomes, who are earth-spirits, and who seem to be a sorrowful race. I once saw some of them distinctly on the side of Ben Bulbin. They had rather round heads and dark thick-set bodies, and in stature were about two and one-half feet. The Leprechauns are different, being full of mischief, though they, too, are small. I followed a Leprechaun from the town of Wicklow out to the Carraig Sidhe, “Rock of[Pg 49] the Fairies,” a distance of half a mile or more, where he disappeared. He had a very merry face, and beckoned to me with his finger. A third class are the Little People, who, unlike the Gnomes and Leprechauns, are quite good-looking; and they are very small. The Good People are tall, beautiful beings, as tall as ourselves…. They direct the magnetic currents of the earth. The Gods are really the Tuatha De Danann, and they are much taller than our race.'”

Wentz: Fairy-faith in Celtic Countries.

The sight of apparitions on Hallowe’en is believed to be fatal to the beholder.

“One night my lady’s soul walked along the wall like a cat. Long Tom Bowman beheld her and that day week fell he into the well and was drowned.”

Pyle: Priest and the Piper.

One version of the Jack-o’-lantern story comes from Ireland. A stingy man named Jack was for his inhospitality barred from all hope of heaven, and because of practical jokes on the Devil was locked out of hell. Until[Pg 50] the Judgment Day he is condemned to walk the earth with a lantern to light his way.

The place of the old lord of the dead, the Tuatha god Saman, to whom vigil was kept and prayers said on November Eve for the good of departed souls, was taken in Christian times by St. Colomba or Columb Kill, the founder of a monastery in Iona in the fifth century. In the seventeenth century the Irish peasants went about begging money and goodies for a feast, and demanding in the name of Columb Kill that fatted calves and black sheep be prepared. In place of the Druid fires, candles were collected and lighted on Hallowe’en, and prayers for the souls of the givers said before them. The name of Saman is kept in the title “Oidhche Shamhna,” “vigil of Saman,” by which the night of October 31st was until recently called in Ireland.

There are no Hallowe’en bonfires in Ireland now, but charms and tests are tried. Apples and nuts, the treasure of Pomona, figure largely in these. They are representative[Pg 51] winter fruits, the commonest. They can be gathered late and kept all winter.

A popular drink at the Hallowe’en gathering in the eighteenth century was milk in which crushed roasted apples had been mixed. It was called lambs’-wool (perhaps from “La Mas Ubhal,” “the day of the apple fruit”). At the Hallowe’en supper “callcannon,” mashed potatoes, parsnips, and chopped onions, is indispensable. A ring is buried in it, and the one who finds it in his portion will be married in a year, or if he is already married, will be lucky.

“They had colcannon, and the funniest things were found in it—tiny dolls, mice, a pig made of china, silver sixpences, a thimble, a ring, and lots of other things. After supper was over all went into the big play-room, and dived for apples in a tub of water, fished for prizes in a basin of flour; then there were games——”

Trant: Hallowe’en in Ireland.

A coin betokened to the finder wealth; the thimble, that he would never marry.

A ring and a nut are baked in a cake. The[Pg 52] ring of course means early marriage, the nut signifies that its finder will marry a widow or a widower. If the kernel is withered, no marriage at all is prophesied. In Roscommon, in central Ireland, a coin, a sloe, and a bit of wood were baked in a cake. The one getting the sloe would live longest, the one getting the wood was destined to die within the year.

A mould of flour turned out on the table held similar tokens. Each person cut off a slice with a knife, and drew out his prize with his teeth.

After supper the tests were tried. In the last century nut-shells were burned. The best-known nut test is made as follows: three nuts are named for a girl and two sweethearts. If one burns steadily with the girl’s nut, that lover is faithful to her, but if either hers or one of the other nuts starts away, there will be no happy friendship between them.

Apples are snapped from the end of a stick hung parallel to the floor by a twisted cord[Pg 53] which whirls the stick rapidly when it is let go. Care has to be taken not to bite the candle burning on the other end. Sometimes this test is made easier by dropping the apples into a tub of water and diving for them, or piercing them with a fork dropped straight down.

Green herbs called “livelong” were plucked by the children and hung up on Midsummer Eve. If a plant was found to be still green on Hallowe’en, the one who had hung it up would prosper for the year, but if it had turned yellow or had died, the child would also die.

Hemp-seed is sown across three furrows, the sower repeating: “Hemp-seed, I saw thee, hemp-seed, I saw thee; and her that is to be my true love, come after me and draw thee.” On looking back over his shoulder he will see the apparition of his future wife in the act of gathering hemp.

Seven cabbage stalks were named for any seven of the company, then pulled up, and the guests asked to come out, and “see their[Pg 54] sowls.”

“Red Mike “was a queer one from his birth, an’ no wonder, for he first saw the light atween dusk an’ dark o’ a Hallowe’en Eve.”

“When the cabbage test was tried at a party where Mike was present, six stalks were found to be white, but Mike’s was “all black an’ fowl wi’ worms an’ slugs, an’ wi’ a real bad smell ahint it.”

“Angered at the ridicule he received, he cried: “I’ve the gift o’ the night, I have, an’ on this day my curse can blast whatever I choose.”

“At that the priest showed Mike a crucifix, and he ran away howling, and disappeared through a bog into the ground. Sharp: Threefold Chronicle.

“Twelve of the party may learn their future, if one gets a clod of earth from the churchyard sets up twelve candles in it, lights and[Pg 55] names them. The fortune of each will be like that of the candle-light named for him,—steady, wavering, or soon in darkness.

“A ball of blue yarn was thrown out of the window by a girl who held fast to the end. She wound it over on her hand from left to right, saying the Creed backwards. When she had nearly finished, she expected the yarn would be held. She must ask “Who holds?” and the wind would sigh her sweetheart’s name in at the window.

“In some charms the devil was invoked directly. If one walked about a rick nine times with a rake, saying, “I rake this rick in the devil’s name,” a vision would come and take away the rake.

“If one went out with nine grains of oats in his mouth, and walked about until he heard a girl’s name called or mentioned, he would know the name of his future wife, for they would be the same.

“Lead is melted, and poured through a key or a ring into cold water. The form each spoonful takes in cooling indicates the occupation[Pg 56] of the future husband of the girl who poured it.

“Now something like a horse would cause the jubilant maiden to call out, ‘A dragoon!’ Now some dim resemblance to a helmet would suggest a handsome member of the mounted police; or a round object with a spike would seem a ship, and this of course meant a sailor; or a cow would suggest a cattle-dealer, or a plough a farmer.” Sharp: Threefold Chronicle.

“After the future had been searched, a piper played a jig, to which all danced merrily with a loud noise to scare away the evil spirits.

“Just before midnight was the time to go out “alone and unperceived” to a south-running brook, dip a shirt-sleeve in it, bring it home and hang it by the fire to dry. One must go to bed, but watch till midnight for a sight of the destined mate who would come to turn the shirt to dry the other side.

“Ashes were raked smooth on the hearth at bedtime on Hallowe’en, and the next morning examined for footprints. If one was[Pg 57] turned from the door, guests or a marriage was prophesied; if toward the door, a death.

“To have prophetic dreams a girl should search for a briar grown into a hoop, creep through thrice in the name of the devil, cut it in silence, and go to bed with it under her pillow.

“A boy should cut ten ivy leaves, throw away one and put the rest under his head before he slept.

“If a girl leave beside her bed a glass of water with a sliver of wood in it, and say before she falls asleep:

Come this night and rescue me,”

“she will dream of falling off a bridge into the water, and of being saved at the last minute by the spirit of her future husband. To receive a drink from his hand she must eat a cake of flour, soot, and salt before she goes to bed.

Yearning for the Unknown

“The Celtic spirit of yearning for the unknown, retained nowhere else as much as in Ireland, is expressed very beautifully by the[Pg 58] poet Yeats in the introduction to his Celtic Twilight.

And over the grave of Clooth-na-bare;

Caolte tossing his burning hair,

And Niam calling: ‘Away, come away;

Filling thy heart with a mortal dream;

For breasts are heaving and eyes a-gleam:

Away, come away to the dim twilight

And if any gaze on our rushing band,

We come between him and the deed of his hand,

We come between him and the hope of his heart.’

And where is there hope or deed as fair?

Caolte tossing his burning hair,

And Niam calling: ‘Away, come away.'”

IN SCOTLAND AND THE HEBRIDES

“As in Ireland the Scotch Baal festival of November was called Samhain. Western Scotland, lying nearest Tara, center alike of pagan and Christian religion in Ireland, was colonized by both the people and the customs of eastern Ireland.

“The November Eve fires which in Ireland either died out or were replaced by candles were continued in Scotland.

“In Buchan, where was the altar-source of the Samhain fire, bonfires were lighted on hilltops in the eighteenth century; and in Moray the idea of fires of thanksgiving for harvest was kept to as late as 1866.

“All through the eighteenth century in the Highlands and in Perthshire torches of heath, broom, flax, or ferns were carried about the fields and villages by each family, with the intent to cause good crops in succeeding years.

The course[Pg 60] about the fields was sunwise, to have a good influence. Brought home at dark, the torches were thrown down in a heap, and made a fire. This blaze was called “Samhnagan,” “of rest and pleasure.” There was much competition to have the largest fire. Each person put in one stone to make a circle about it. The young people ran about with burning brands. Supper was eaten out-of-doors, and games played. After the fire had burned out, ashes were raked over the stones. In the morning each sought his pebble, and if he found it misplaced, harmed, or a footprint marked near it in the ashes, he believed he should die in a year.

“In Aberdeenshire boys went about the villages saying: “Ge’s a peat t’ burn the witches.” They were thought to be out stealing milk and harming cattle. Torches used to counteract them were carried from west to east, against the sun. This ceremony grew into a game, when a fire was built by one party, attacked by another, and defended.

“As in the May fires of purification the lads lay[Pg 61] down in the smoke close by, or ran about and jumped over the flames. As the fun grew wilder they flung burning peats at each other, scattered the ashes with their feet, and hurried from one fire to another to have a part in scattering as many as possible before they died out.

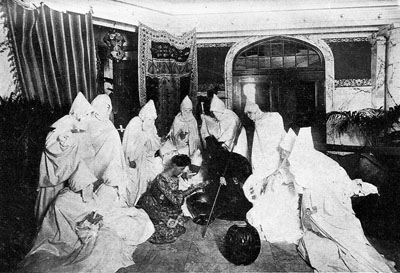

“In 1874, at Balmoral, a royal celebration of Hallowe’en was recorded. Royalty, tenants, and servants bore torches through the grounds and round the estates. In front of the castle was a heap of stuff saved for the occasion. The torches were thrown on. When the fire was burning its liveliest, a hobgoblin appeared, drawing in a car the figure of a witch, surrounded by fairies carrying lances. The people formed a circle about the fire, and the witch was tossed in. Then there were dances to the music of bag-pipes.

“It was the time of year when servants changed masters or signed up anew under the old ones. They might enjoy a holiday before resuming work. So they sang:

Nine free nichts till Martinmas,

As soon they’ll wear away.”

“Children born on Hallowe’en could see and converse with supernatural powers more easily than others.

“In Ireland, evil relations caused Red Mike’s downfall (q. v.). For Scotland Mary Avenel, in Scott’s Monastery, is the classic example.

“And touching the bairn, it’s weel kenn’d she was born on Hallowe’en, and they that are born on Hallowe’en whiles see mair than ither folk.”

“There is no hint of dark relations, but rather of a clear-sightedness which lays bare truths, even those concealed in men’s breasts. Mary Avenel sees the spirit of her father after he has been dead for years. The White Lady of Avenel is her peculiar guardian.

The Scottish Border, where Mary lived, is the seat of many superstitions and other worldly beliefs. The fairies of Scotland are more terrible than those of Ireland, as the dells and streams and woods are of greater[Pg 63] grandeur, and the character of the people more serious. It is unlucky to name the fairies, here as elsewhere, except by such placating titles as “Good Neighbors” or “Men of Peace.” Rowan, elm, and holly are a protection against them.

“I have tied red thread round the bairns’ throats, and given ilk ane of them a riding-wand of rowan-tree, forbye sewing up a slip of witch-elm into their doublets; and I wish to know of your reverence if there be onything mair that a lone woman can do in the matter of ghosts and fairies?—be here! that I should have named their unlucky names twice ower!” Scott: Monastery.

“The sign of the cross disarmeth all evil spirits.”

“These spirits of the air have not human feelings or motives. They are conscienceless.

Peter Pan

In this respect Peter Pan is an immortal fairy as well as an immortal child. While like a child he resents injustice in horrified silence, like a fairy he acts with no sense of responsibility. When he saves Wendy’s brother from[Pg 64] falling as they fly,

“You felt it was his cleverness that interested him, and not the saving of human life.” Barrie: Peter and Wendy.

“The world in which Peter lived was so near the Kensington Gardens that he could see them through the bridge as he sat on the shore of the Neverland. Yet for a long time he could not get to them.

“Peter is a fairy piper who steals away the souls of children.

Hopper: Fairy Fiddler.

“On Hallowe’en all traditional spirits are abroad. The Scotch invented the idea of a “Samhanach,” a goblin who comes out just at “Samhain.” It is he who in Ireland steals[Pg 65] children. The fairies pass at crossroads,

The morn is Hallowday;

Then win me, win me, and ye will,

The fairy folk will ride.

And they that wad their true-love win,

At Miles Cross they maun bide.”

Ballad of Tam Lin.

“and in the Highlands whoever took a three-legged stool to where three crossroads met, and sat upon it at midnight, would hear the names of those who were to die in a year. He might bring with him articles of dress, and as each name was pronounced throw one garment to the fairies. They would be so pleased by this gift that they would repeal the sentence of death.

Even people who seemed to be like their neighbors every day could for this night fly away and join the other beings in their[Pg 66] revels.

When a’ the witchie may be seen;

Some o’ them black, some o’ them green,

Some o’ them like a turkey bean.”

“A witches’ party was conducted in this way. The wretched women who had sold their souls to the Devil, left a stick in bed which by evil means was made to have their likeness, and, anointed with the fat of murdered babies flew off up the chimney on a broomstick with cats attendant. Burns tells the story of a company of witches pulling ragwort by the roadside, getting each astride her ragwort with the summons “Up horsie!” and flying away.

Herrick: The Hag.

The meeting-place was arranged by the Devil, who sometimes rode there on a goat. At their supper no bread or salt was eaten; they drank out of horses’ skulls, and danced, sometimes back to back, sometimes from west to east, for the dances at the ancient Baal festivals were from east to west, and it was evil and ill-omened to move the other way. For this dance the Devil played a bag-pipe made of a hen’s skull and cats’ tails.

Burns: Tam o’ Shanter.

[1]Ring.

The light for the revelry came from a torch[Pg 68] flaring between the horns of the Devil’s steed the goat, and at the close the ashes were divided for the witches to use in incantations. People imagined that cats who had been up all night on Hallowe’en were tired out the next morning.

Tam o’ Shanter who was watching such a dance

in Ayrshire, could not resist calling out at the antics of a neighbor whom he recognized, and was pursued by the witches. He urged his horse to top-speed,

Burns: Tam o’ Shanter.

but poor Meg had no tail thereafter to toss at them, for though she saved her rider, she was only her tail’s length beyond the middle of the bridge when the foremost witch grasped[Pg 69] it and seared it to a stub.

Such witches might be questioned about the past or future.

Scott: St. Swithin’s Chair.

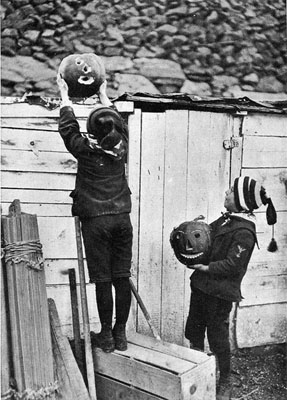

Children make of themselves bogies on this evening, carrying the largest turnips they can save from harvest, hollowed out and carved into the likeness of a fearsome face, with teeth and forehead blacked, and lighted by a candle fastened inside.

If the spirit of a person simply appears without being summoned, and the person is still alive, it means that he is in danger. If he comes toward the one to whom he appears the danger is over. If he seems to go away, he is dying.

An apparition from the future especially is sought on Hallowe’en. It is a famous time for divination in love affairs. A typical[Pg 70] eighteenth century party in western Scotland is described by Robert Burns.

Cabbages are important in Scotch superstition. Children believe that if they pile cabbage-stalks round the doors and windows of the house, the fairies will bring them a new brother or sister.

Buchanan: Willie Baird.

Kale-pulling came first on the program in Burns’s Hallowe’en. Just the single and unengaged went out hand in hand blindfolded to the cabbage-garden. They pulled the first stalk they came upon, brought it back to the house, and were unbandaged. The size and shape of the stalk indicated the appearance of the future husband or wife.

“Maybe you would rather not pull a stalk[Pg 71] that was tall and straight and strong—that would mean Alastair? Maybe you would rather find you had got hold of a withered old stump with a lot of earth at the root—a decrepit old man with plenty of money in the bank? Or maybe you are wishing for one that is slim and supple and not so tall—for one that might mean Johnnie Semple.”

Black: Hallowe’en Wraith.

A close white head meant an old husband, an open green head a young one. His disposition would be like the taste of the stem. To determine his name, the stalks were hung over the door, and the number of one’s stalk in the row noted. If Jessie put hers up third from the beginning, and the third man who passed through the doorway under it was named Alan, her husband’s first name would be Alan. This is practised only a little now among farmers. It has special virtue if the cabbage has been stolen from the garden of an unmarried person.

Sometimes the pith of a cabbage-stalk was pushed out, the hole filled with tow, which was set afire and blown through keyholes on[Pg 72] Hallowe’en.

Dick: Splores of a Hallowe’en.

Cabbage-broth was a regular dish at the Hallowe’en feast. Mashed potatoes, as in Ireland, or a dish of meal and milk holds symbolic objects—a ring, a thimble, and a coin. In the cake are baked a ring and a key. The ring signifies to the possessor marriage, and the key a journey.

Apple-ducking is still a universal custom in Scotland. A sixpence is sometimes dropped into the tub or stuck into an apple to make the reward greater. The contestants must keep their hands behind their backs.

Nuts are put before the fire in pairs, instead[Pg 73] of by threes as in Ireland, and named for a lover and his lass. If they burn to ashes together, long happy married life is destined for the lovers. If they crackle or start away from each other, dissension and separation are ahead.

Burns: Hallowe’en.

[1]Careful.

[2]Chimney.

Three “luggies,” bowls with handles like the Druid lamps, were filled, one with clean, one with dirty water, and one left empty. The person wishing to know his fate in marriage was blindfolded, turned about thrice, and put down his left hand. If he dipped it into the clean water, he would marry a[Pg 74] maiden; if into the dirty, a widow; if into the empty dish, not at all. He tried until he got the same result twice. The dishes were changed about each time.

This spell still remains, as does that of hemp-seed sowing. One goes out alone with a handful of hemp-seed, sows it across ridges of ploughed land, and harrows it with anything convenient, perhaps with a broom. Having said:

Burns: Hallowe’en.

he looks behind him to see his sweetheart gathering hemp. This should be tried just at midnight with the moon behind.

Gay: Pastorals.

A spell that has been discontinued is throwing the clue of blue yarn into the kiln-pot, instead of out of the window, as in Ireland. As it is wound backward, something holds it. The winder must ask, “Wha hauds?” to hear the name of her future sweetheart.

Burns: Hallowe’en.

[1]Cross-beam.

[2]Ask.

Another spell not commonly tried now is winnowing three measures of imaginary corn, as one stands in the barn alone with both doors open to let the spirits that come in go[Pg 76] out again freely. As one finishes the motions, the apparition of the future husband will come in at one door and pass out at the other.

“‘I had not winnowed the last weight clean out, and the moon was shining bright upon the floor, when in stalked the presence of my dear Simon Glendinning, that is now happy. I never saw him plainer in my life than I did that moment; he held up an arrow as he passed me, and I swarf’d awa’ wi’ fright…. But mark the end o’ ‘t, Tibb: we were married, and the grey-goose wing was the death o’ him after a’.'”

Scott: The Monastery.

At times other prophetic appearances were seen.

“Just as she was at the wark, what does she see in the moonlicht but her ain coffin moving between the doors instead of the likeness of a gudeman! and as sure’s death she was in her coffin before the same time next year.”

Anon: Tale of Hallowe’en.

Formerly a stack of beans, oats, or barley was measured round with the arms against[Pg 77] sun. At the end of the third time the arms would enclose the vision of the future husband or wife.

Kale-pulling, apple-snapping, and lead-melting (see Ireland) are social rites, but many were to be tried alone and in secret. A Highland divination was tried with a shoe, held by the tip, and thrown over the house. The person will journey in the direction the toe points out. If it falls sole up, it means bad luck.

Girls would pull a straw each out of a thatch in Broadsea, and would take it to an old woman in Fraserburgh. The seeress would break the straw and find within it a hair the color of the lover’s-to-be. Blindfolded they plucked heads of oats, and counted the number of grains to find out how many children they would have. If the tip was perfect, not broken or gone, they would be married honorably.

Another way of determining the number of children was to drop the white of an egg into a glass of water. The number of divisions[Pg 78] was the number sought. White of egg is held with water in the mouth, like the grains of oats in Ireland, while one takes a walk to hear mentioned the name of his future wife. Names are written on papers, and laid upon the chimney-piece. Fate guides the hand of a blindfolded man to the slip which bears his sweetheart’s name.

A Hallowe’en mirror is made by the rays of the moon shining into a looking-glass. If a girl goes secretly into a room at midnight between October and November, sits down at the mirror, and cuts an apple into nine slices, holding each on the point of a knife before she eats it, she may see in the moonlit glass the image of her lover looking over her left shoulder, and asking for the last piece of apple.

The wetting of the sark-sleeve in a south-running burn where “three lairds’ lands meet,” and carrying it home to dry before the fire, was really a Scotch custom, but has already been described in Ireland.

Burns: Tam Glen.

[1]Watching.

[2]Drenched.

Just before breaking up, the crowd of young people partook of sowens, oatmeal porridge cakes with butter, and strunt, a liquor, as they hoped for good luck throughout the year.

The Hebrides, Scottish islands off the western coast, have Hallowe’en traditions of their own, as well as many borrowed from Ireland and Scotland. Barra, isolated near the end of the island chain, still celebrates the Celtic days, Beltaine and November Eve.

In the Hebrides is the Irish custom of eating on Hallowe’en a cake of meal and salt, or a salt herring, bones and all, to dream of some one bringing a drink of water. Not a word must be spoken, nor a drop of water drunk till the dream comes.

In St. Kilda a large triangular cake is baked which must be all eaten up before morning.

A curious custom that prevailed in the[Pg 80] island of Lewis in the eighteenth century was the worship of Shony, a sea-god with a Norse name. His ceremonies were similar to those paid to Saman in Ireland, but more picturesque. Ale was brewed at church from malt brought collectively by the people. One took a cupful in his hand, and waded out into the sea up to his waist, saying as he poured it out: “Shony, I give you this cup of ale, hoping that you’ll be so kind as to send us plenty of sea-ware, for enriching our ground the ensuing year.” The party returned to the church, waited for a given signal when a candle burning on the altar was blown out. Then they went out into the fields, and drank ale with dance and song.

The “dumb cake” originated in Lewis. Girls were each apportioned a small piece of dough, mixed with any but spring water. They kneaded it with their left thumbs, in silence. Before midnight they pricked initials on them with a new pin, and put them by the fire to bake. The girls withdrew to the farther end of the room, still in[Pg 81] silence. At midnight each lover was expected to enter and lay his hand on the cake marked with his initials.

In South Uist and Eriskay on Hallowe’en fairies are out, a source of terror to those they meet.

But for the most part this belief has died out on Scottish land, except near the Border, and Hallowe’en is celebrated only by stories and jokes and games, songs and dance.

IN ENGLAND AND MAN

Man especially has a treasury of fairy tradition, Celtic and Norse combined. Manx fairies too dwell in the middle world, since they are fit for neither heaven nor hell. Even now Manx people think they see circles of light in the late October midnight, and little folk dancing within.

Longest of all in Man was Sauin (Samhain) considered New Year’s Day. According to the old style of reckoning time it came on November 12.

Mummers’ Song.

As in Scotland the servants’ year ends with October.

New Year tests for finding out the future were tried on Sauin. To hear her sweetheart’s name a girl took a mouthful of water[Pg 83] and two handfuls of salt, and sat down at a door. The first name she heard mentioned was the wished-for one. The three dishes proclaimed the fate of the blindfolded seeker as in Scotland. Each was blindfolded and touched one of several significant objects—meal for prosperity, earth for death, a net for tangled fortunes.

Before retiring each filled a thimble with salt, and emptied it out in a little mound on a plate, remembering his own. If any heap were found fallen over by morning, the person it represented was destined to die in a year. The Manx looked for prints in the smooth-strewn ashes on the hearth, as the Scotch did, and gave the same interpretation.

There had been Christian churches in Britain as early as 300 a. d., and Christian missionaries, St. Ninian, Pelagius, and St. Patrick, were active in the next century, and in the course of time St. Augustine. Still the old superstitions persisted, as they always do when they have grown up with the people.

King Arthur, who was believed to have[Pg 84] reigned in the fifth century, may be a personification of the sun-god. He comes from the Otherworld, his magic sword Excalibur is brought thence to him, he fights twelve battles, in number like the months, and is wounded to death by evil Modred, once his own knight. He passes in a boat, attended by his fairy sister and two other queens,

Tennyson: Passing of Arthur.

The hope of being healed there is like that given to Cuchulain (q. v.), to persuade him to visit the fairy kingdom. Arthur was expected to come again sometime, as the sun renews his course. As he disappeared from the sight of Bedivere, the last of his knights,

Ibid.

Avilion means “apple-island.” It was like[Pg 85] the Hesperides of Greek mythology, the western islands where grew the golden apples of immortality.

In Cornwall after the sixth century, the sun-god became St. Michael, and the eastern point where he appeared St. Michael’s seat.

Looks toward Namancos, and Bayona’s hold.”

Milton: Lycidas.

As fruit to Pomona, so berries were devoted to fairies. They would not let any one cut a blackthorn shoot on Hallowe’en. In Cornwall sloes and blackberries were considered unfit to eat after the fairies had passed by, because all the goodness was extracted. So they were eaten to heart’s content on October 31st, and avoided thereafter. Hazels, because they were thought to contain wisdom and knowledge, were also sacred.

Besides leaving berries for the “Little People,” food was set out for them on Hallowe’en, and on other occasions. They rewarded this hospitality by doing an extraordinary[Pg 86] amount of work.

To earn his cream-bowl duly set,

When in one night, ere glimpse of morn,

His shadowy flail hath threshed the corn

That ten day-laborers could not end.

Then lies him down the lubbar fiend,

And stretcht out all the chimney’s length

Basks at the fire his hairy strength.”

Milton: L’Allegro.

Such sprites did not scruple to pull away the chair as one was about to sit down, to pinch, or even to steal children and leave changelings in their places. The first hint of dawn drove them back to their haunts.

Jonson: Robin Goodfellow.

Soulless and without gratitude or memory[Pg 87] spirits of the air may be, like Ariel in The Tempest. He, like the fairy harpers of Ireland, puts men to sleep with his music.

Shakspere: The Tempest.

The people of England, in common with those who lived in the other countries of Great Britain and in Europe, dreaded the coming of winter not only on account of the cold and loneliness, but because they believed that at this time the powers of evil were abroad and ascendant. This belief harked back to the old idea that the sun had been vanquished by his enemies in the late autumn. It was to forget the fearful influences about them that the English kept festival so much in the[Pg 88] winter-time. The Lords of Misrule, leaders of the revelry, “beginning their rule on All Hallow Eve, continued the same till the morrow after the Feast of the Purification, commonlie called Candelmas day: In all of which space there were fine and subtle disguisinges, Maskes, and Mummeries.” This was written of King Henry IV’s court at Eltham, in 1401, and is true of centuries before and after. They gathered about the fire and made merry while the October tempests whirled the leaves outside, and shrieked round the house like ghosts and demons on a mad carousal.

Without—October’s tempests scowl,

As he troops away on the raving wind!

And leaveth dry leaves in his path behind.

Coxe: Hallowe’en.

[1]Devils.

Witchcraft—the origin of which will be traced farther on—had a strong following in England. The three witches in Macbeth are really fates who foretell the future, but they have a kettle in which they boil

Shakspere: Macbeth.

They connect themselves thereby with those evil creatures who pursued Tam o’ Shanter, and were servants of the Devil. In 1892 in Lincolnshire, people believed that if they looked in through the church door on Hallowe’en they would see the Devil preaching his doctrines from the pulpit, and inscribing[Pg 90] the names of new witches in his book.

The Spectre Huntsman, known in Windsor Forest as Herne the Hunter, and in Todmorden as Gabriel Ratchets, was the spirit of an ungodly hunter who for his crimes was condemned to lead the chase till the Judgment Day. In a storm on Hallowe’en is heard the belling of his hounds.

Scott: Wild Huntsman.

In the north of England Hallowe’en was called “nut-crack” and “snap-apple night.” It was celebrated by “young people and sweethearts.”

A variation of the nut test is, naming two for two lovers before they are put before[Pg 91] the fire to roast. The unfaithful lover’s nut cracks and jumps away, the loyal burns with a steady ardent flame to ashes.

Gay: The Spell.

If they jump toward each other, they will be rivals. If one of the nuts has been named for the girl and burns quietly with a lover’s nut, they will live happily together. If they are restless, there is trouble ahead.

Graydon: On Nuts Burning, Allhallows Eve.

Sometimes peas on a hot shovel are used instead.

Down the centuries from the Druid tree-worship comes the spell of the walnut-tree. It is circled thrice, with the invocation: “Let her that is to be my true-love bring me some walnuts;” and directly a spirit will be seen in the tree gathering nuts.

Gay: Pastorals.

The seeds of apples were used in many trials. Two stuck on cheeks or eyelids indicated by the time they clung the faithfulness of the friends named for them.

Gay: Pastorals.

In a tub float stemless apples, to be seized by the teeth of him desirous of having his love returned. If he is successful in bringing up the apple, his love-affair will end happily.

Munkittrick: Hallowe’en Wish.

An apple is peeled all in one piece, and the paring swung three times round the head and dropped behind the left shoulder. If it does not break, and is looked at over the shoulder it forms the initial of the true sweetheart’s name.

Gay: Pastorals.

In the north of England was a unique custom, “the scadding of peas.” A pea-pod was slit, a bean pushed inside, and the opening closed again. The full pods were boiled, and apportioned to be shelled and the peas eaten with butter and salt. The one finding the bean on his plate would be married first. Gay records another test with peas which is[Pg 95] like the final trial made with kale-stalks.

Gay: Pastorals.

Candles, relics of the sacred fire, play an important part everywhere on Hallowe’en. In England too the lighted candle and the apple were fastened to the stick, and as it whirled, each person in turn sprang up and tried to bite the apple.

This was a rough game, more suited to boys’ frolic than the ghostly divinations that preceded it. Those with energy to spare found material to exercise it on. In an old book there is a picture of a youth sitting on a stick placed across two stools. On one end of the[Pg 96] stick is a lighted candle from which he is trying to light another in his hand. Beneath is a tub of water to receive him if he over-balances sideways. These games grew later into practical jokes.

The use of a goblet may perhaps come from the story of “The Luck of Edenhall,” a glass stolen from the fairies, and holding ruin for the House by whom it was stolen, if it should ever be broken. With ring and goblet this charm was tried: the ring, symbol of marriage, was suspended by a hair within a glass, and a name spelled out by beginning the alphabet over each time the ring struck the glass.

When tired of activity and noise, the party gathered about a story-teller, or passed a bundle of fagots from hand to hand, each selecting one and reciting an installment of the tale till his stick burned to ashes.

Coxe: Hallowe’en.

To induce prophetic dreams the wood-and-water[Pg 97] test was tried in England also.

Gay: Pastorals.

Though Hallowe’en is decidedly a country festival, in the seventeenth century young gentlemen in London chose a Master of the Revels, and held masques and dances with their friends on this night.

In central and southern England the ecclesiastical side of Hallowtide is stressed.

Bread or cake has till recently (1898) been as much a part of Hallowe’en preparations as plum pudding at Christmas. Probably this originated from an autumn baking of bread from the new grain. In Yorkshire each person gets a triangular seed-cake, and the evening is called “cake night.”

Tusser: Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry, 1580.

Cakes appear also at the vigil of All Souls’, the next day. At a gathering they lie in a heap for the guests to take. In return they are supposed to say prayers for the dead.

Old Saying.

The poor in Staffordshire and Shropshire went about singing for soul-cakes or money, promising to pray and to spend the alms in masses for the dead. The cakes were called Soul-mass or “somas” cakes.

Notes and Queries.

In Dorsetshire Hallowe’en was celebrated[Pg 99] by the ringing of bells in memory of the dead. King Henry VIII and later Queen Elizabeth issued commands against this practice.

In Lancashire in the early nineteenth century people used to go about begging for candles to drive away the gatherings of witches. If the lights were kept burning till midnight, no evil influence could remain near.

In Derbyshire, central England, torches of straw were carried about the stacks on All Souls’ Eve, not to drive away evil spirits, as in Scotland, but to light souls through Purgatory.

Like the Bretons, the English have the superstition that the dead return on Hallowe’en.

Letts: Hallowe’en.

IN WALES

In Wales the custom of fires persisted from the time of the Druid festival-days longer than in any other place. First sacrifices were burned in them; then instead of being burned to death, the creatures merely passed through the fire; and with the rise of Christianity fire was thought to be a protection against the evil power of the same gods.

Pontypridd, in South Wales, was the Druid religious center of Wales. It is still marked by a stone circle and an altar on a hill. In after years it was believed that the stones were people changed to that form by the power of a witch.

In North Wales the November Eve fire, which each family built in the most prominent place near the house, was called Coel Coeth. Into the dying fire each member of the family threw a white stone marked so[Pg 102] that he could recognize it again. Circling about the fire hand-in-hand they said their prayers and went to bed. In the morning each searched for his stone, and if he could not find it, he believed that he would die within the next twelve months. This is still credited. There is now the custom also of watching the fires till the last spark dies, and instantly rushing down hill, “the devil (or the cutty black sow) take the hindmost.” A Cardiganshire proverb says:

[1]Short-tailed.

November Eve was called “Nos-Galan-Gaeof,” the night of the winter Calends, that is, the night before the first day of winter. To the Welsh it was New Year’s Eve.

Welsh fairy tradition resembles that in the near-by countries. There is an old story of a man who lay down to sleep inside a fairy[Pg 103] ring, a circle of greener grass where the fairies danced by night. The fairies carried him away and kept him seven years, and after he had been rescued from them he would neither eat nor speak.

In the sea was the Otherworld, a

Parry: Welsh Melodies.

This was the abode of the Druids, and hence of all supernatural beings, who were

Scott: The Monastery.

As in other countries the fairies or pixies are to be met at crossroads, where happenings, such as funerals, may be witnessed weeks before they really occur.

At the Hallow Eve supper parsnips and cakes are eaten, and nuts and apples roasted. A “puzzling jug” holds the ale. In the rim are three holes that seem merely ornamental.[Pg 104] They are connected with the bottom of the jug by pipes through the handle, and the unwitting toper is well drenched unless he is clever enough to see that he must stop up two of the holes, and drink through the third.

Spells are tried in Wales too with apples and nuts. There is ducking and snapping for apples. Nuts are thrown into the fire, denoting prosperity if they blaze brightly, misfortune if they pop, or smoulder and turn black.

“Old Pally threw on a nut. It flickered and then blazed up. Maggee tossed one into the fire. It smouldered and gave no light.”

Marks: All-Hallows Honeymoon.

Fate is revealed by the three luggies and the ball of yarn thrown out of the window: Scotch and Irish charms. The leek takes the place of the cabbage in Scotland. Since King Cadwallo decorated his soldiers with leeks for their valor in a battle by a leek-garden, they have been held in high esteem in Wales. A[Pg 105] girl sticks a knife among leeks at Hallowe’en, and walks backward out of the garden. She returns later to find that her future husband has picked up the knife and thrown it into the center of the leek-bed.

Taking two long-stemmed roses, a girl goes to her room in silence. She twines the stems together, naming one for her sweetheart and the other for herself, and thinking this rhyme:

She can see, by watching closely, her lover’s rose grow darker.

The sacred ash figures in one charm. The party of young people seek an even-leaved sprig of ash. The first who finds one calls out “cyniver.” If a boy calls out first, the first girl who finds another perfect shoot bears the name of the boy’s future wife.

Dancing and singing to the music of the[Pg 106] harp close the evening.

Instead of leaving stones in the fire to determine who are to die, people now go to church to see by the light of a candle held in the hand the spirits of those marked for death, or to hear the names called. The wind “blowing over the feet of the corpses” howls about the doors of those who will not be alive next Hallowe’en.

On the Eve of All Souls’ Day, twenty-four hours after Hallowe’en, children in eastern Wales go from house to house singing for

It is a time when charity is given freely to the poor. On this night and the next day, fires are burned, as in England, to light souls through Purgatory, and prayers are made for a good wheat harvest next year by the Welsh, who keep the forms of religion very devoutly.

CHAPTER XI

IN BRITTANY AND FRANCE

The Celts had been taught by their priests that the soul is immortal. When the body died the spirit passed instantly into another existence in a country close at hand. We remember that the Otherworld of the British Isles, peopled by the banished Tuatha and all superhuman beings, was either in caves in the earth, as in Ireland, or in an island like the English Avalon. By giving a mortal one of their magic apples to eat, fairies could entice him whither they would, and at last away into their country.

In the Irish story of Nera (q. v.), the corpse of the criminal is the cause of Nera’s being lured into the cave. So the dead have the same power as fairies, and live in the same place. On May Eve and November Eve the dead and the fairies hold their revels together and make excursions together. If a young person died, he was said to be called away by[Pg 108] the fairies. The Tuatha may not have been a race of gods, but merely the early Celts, who grew to godlike proportions as the years raised a mound of lore and legends for their pedestal. So they might really be only the dead, and not of superhuman nature.

In the fourth century a. d., the men of England were hard pressed by the Picts and Scots from the northern border, and were helped in their need by the Teutons. When this tribe saw the fair country of the Britons they decided to hold it for themselves. After they had driven out the northern tribes, in the fifth century, when King Arthur was reigning in Cornwall, they drove out those whose cause they had fought. So the Britons were scattered to the mountains of Wales, to Cornwall, and across the Channel to Armorica, a part of France, which they named Brittany after their home-land. In lower Brittany, out of the zone of French influence, a language something like Welsh or old British is still spoken, and many of the Celtic beliefs were retained more untouched than in[Pg 109] Britain, not clear of paganism till the seventeenth century. Here especially did Christianity have to adapt the old belief to her own ends.

Gaul, as we have seen from Cæsar’s account, had been one of the chief seats of Druidical belief. The religious center was Carnutes, now Chartrain. The rites of sacrifice survived in the same forms as in the British Isles. In the fields of Deux-Sèvres fires were built of stubble, ferns, leaves, and thorns, and the people danced about them and burned nuts in them. On St. John’s Day animals were burned in the fires to secure the cattle from disease. This was continued down into the seventeenth century.

The pagan belief that lasted the longest in Brittany, and is by no means dead yet, was the cult of the dead. Cæsar said that the Celts of Gaul traced their ancestry from the god of death, whom he called Dispater. Now figures of l’Ankou, a skeleton armed with a spear, can be seen in most villages of Brittany. This mindfulness of death was strengthened[Pg 110] by the sight of the prehistoric cairns of stones on hilltops, the ancient altars of the Druids, and dolmens, formed of one flat rock resting like a roof on two others set up on end with a space between them, ancient tombs; and by the Bretons being cut off from the rest of France by the nature of the country, and shut in among the uplands, black and misty in November, and blown over by chill Atlantic winds. Under a seeming dull indifference and melancholy the Bretons conceal a lively imagination, and no place has a greater wealth of legendary literature.

What fairies, dwarfs, pixies, and the like are to the Celts of other places, the spirits of the dead are to the Celts of Brittany. They possess the earth on Christmas, St. John’s Day, and All Saints’. In Finistère, that western point of France, there is a saying that on the Eve of All Souls’ “there are more dead in every house than sands on the shore.” The dead have the power to charm mortals and take them away, and to foretell the future. They must not be spoken of directly,[Pg 111] any more than the fairies of the Scottish border, or met with, for fear of evil results.