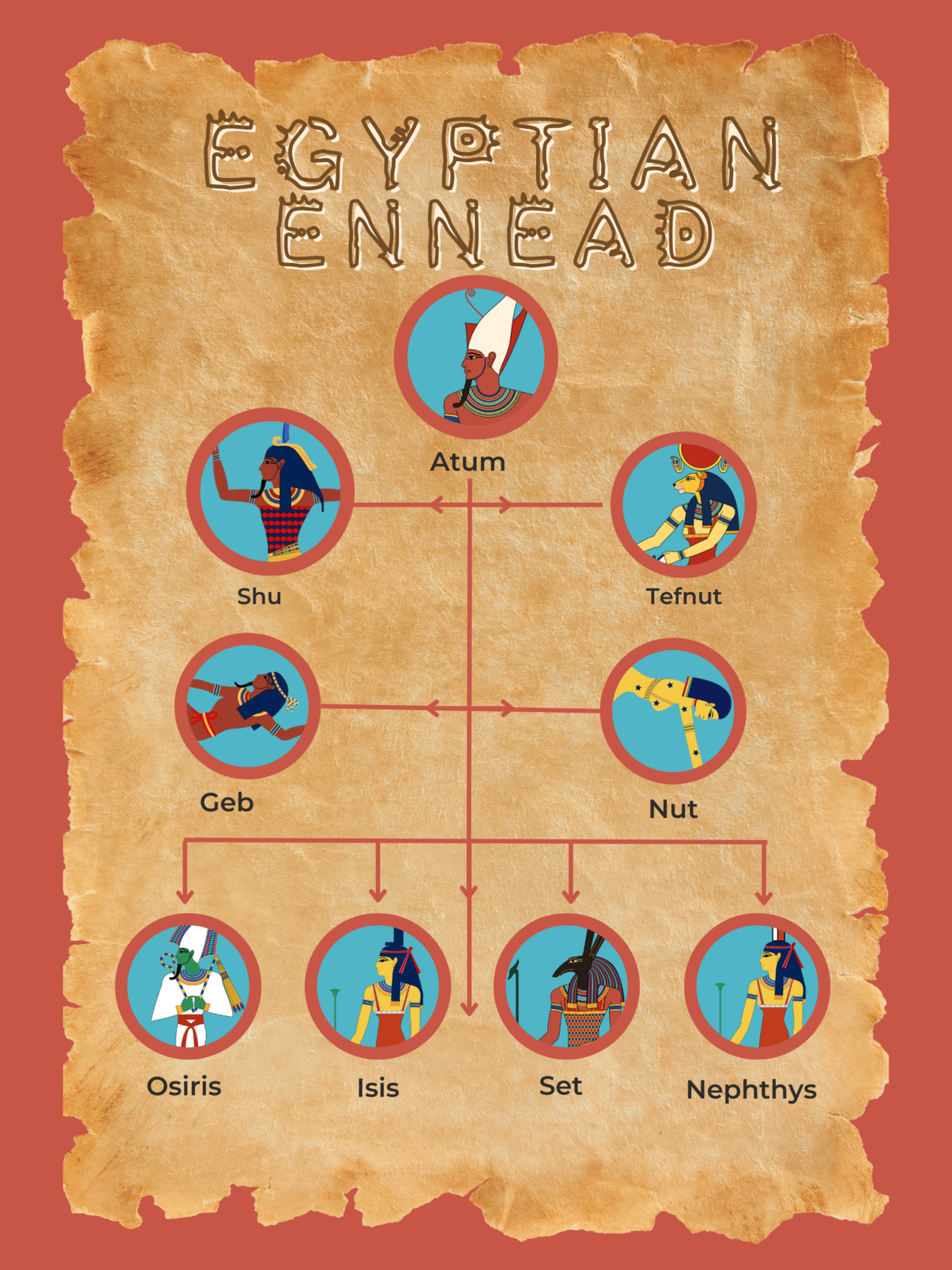

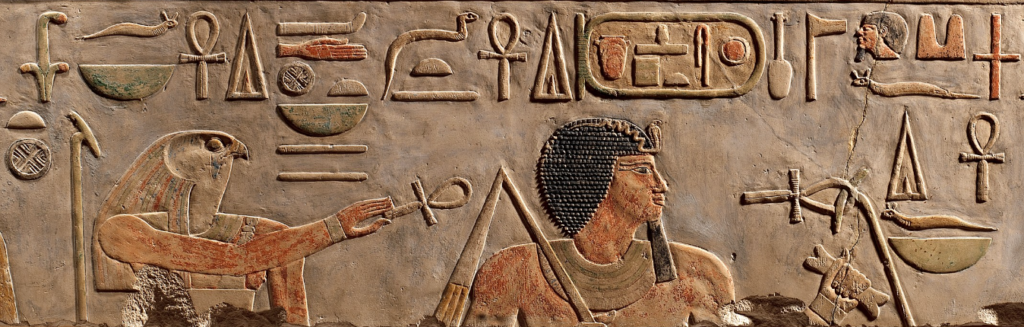

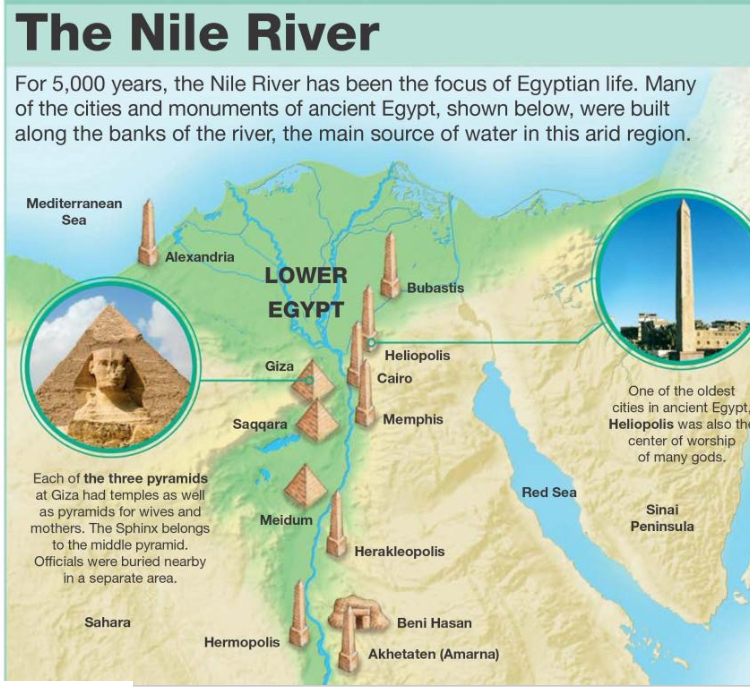

The Ennead

“Ancient Egyptians had several myths regarding the creation of the world. One of the most popular creation myths featured the Ennead, a group of nine ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses. Atum was thought to be the first god and creator of the world and from Atum the Ennead were born.” British Museum

Deities in the Ennead

Atum – Image Credit British Museum

Geb – Image Credit British Museum

|

|

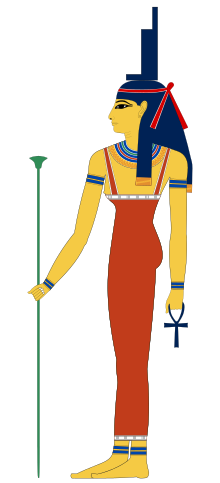

Isis – Image Credit British Museum

Nephthys -Image Credit British Museum

Nut – Image Credit British Museum

Osiris -Image Credit British Museum

Set -Image Credit British Museum

Shu – Image Credit British Museum

Tefnut – Image Credit British Museum

A List of Ancient Egyptian Deities

Ammit

Image Credit: British Museum

Ammit depicted with the head of a crocodile, the forelegs of a lion and the hind legs of a hippopotamus. Ammit © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- Not considered a goddess, but rather a powerful and terrifying creature who had supernatural powers.

- Often depicted with the head of a crocodile, the forelegs of a lion and the hind legs of a hippopotamus.

- Ammit’s name means ‘the devourer’, because she was believed to devour the hearts of the deceased if they were found to be unworthy during the judgment of the dead.

- She lived next to the scales of justice in the underworld, which was where the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of truth.

- Frequently shown in Egyptian funeral art – her image served as a warning to the deceased to live a good life and avoid wrongdoing. British Museum

Amun and Amun-Ra

Amun and Amun-Ra

Image Credit: British Museum

“These two most common depictions of Amun and Amun-Ra were used interchangeably for both gods. Amun (on the left) ” British Museum © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence(Opens in new window); Amun (on the right) © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- Amun was originally part of the Ogdoad, a group of eight gods from another creation myth.

- He was also known as ‘the hidden one’ and was thought to be a mysterious, secret god with many aspects.

- He was often portrayed as a man with red or blue skin, wearing a headdress of two feathers, or as a ram-headed man.

- By the Middle Kingdom, Amun became linked with the king and was considered a protector of the royal family – and king of the gods.

- Amun was married to Mut, and father of Khonsu – he was also shown as the father of many pharaohs.

- In the New Kingdom, Amun was combined with the sun god Ra to form the powerful god Amun-Ra.

- Worshipped throughout Egypt – his temple at Karnak was one of the largest and most impressive in the ancient world. British Museum

Anubis

Image Credit: British Museum

“Anubis depicted as a man with the head of a jackal. Anubis © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- God of mummification, the afterlife and the dead.

- Often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal or as a full jackal.

- Responsible for preparing the deceased for the afterlife and guiding them through the underworld.

- Associated with rituals of mourning and sometimes depicted as a protector of the dead.

- Worshipped throughout Egypt – his presence was felt during the entire process of preparing a body for burial and ensuring a successful afterlife.

- Despite his powerful and important role, Anubis was also seen as a gentle and caring god who took great care in ensuring that the dead were treated with respect. British Museum

Aten

Image Credit: British Museum

“Aten portrayed as a sun disc with rays ending in hands. Aten © AtonX, shared under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence”

- A solar god who was often portrayed as a sun disc with rays ending in hands.

- The giver of life, light, energy and food, and often shown as a bright and powerful force.

- During the reign of the pharaoh Akhenaten, the Aten became the main god of Egypt, and Akhenaten banned the worship of other gods.

- Not widely worshipped outside of the reign of Akhenaten and his cult faded away after Akhenaten’s death. British Museum

Atum

Image Credit: British Museum

“Atum depicted as a man wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. Atum © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 ”

- According to one popular ancient Egyptian myth, he created the world.

- Often depicted as a man wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.

- Sometimes associated with the evening sun – ancient Egyptians believed that he travelled across the sky during the day and passed through the underworld at night before being reborn at dawn.

- Sometimes depicted as an old man, representing the end of life – he was thought to be reborn every day with the rising sun.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above.

- Believed to have created Shu (the god of air) and Tefnut (the goddess of moisture) also part of the Ennead. British Museum

Bastet

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Bastet depicted with the head of a cat and the body of a human. Bastet © Eternal Space, shared under a CC0 1.0 licence”

- Goddess of cats, fertility (new life) and childbirth, and often associated with joy and dance.

- Frequently depicted with the head of a cat and the body of a human.

- Often worshipped by Egyptians who owned cats – cats were considered sacred animals in ancient Egypt.

- Believed to have the power to protect against evil spirits and diseases – her image was often used as a symbol of good luck and protection.

- Considered to be a gentler version of the lion-goddess Sekhmet. British Museum

Bes

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Bes depicted as a short, bearded man, wearing a feather headdress. Bes © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Often shown as a short, bearded man with a lion’s mane and tail, wearing a feather headdress.

- Ancient Egyptians considered those with dwarfism – including Bes – to be magical and they were sometimes appointed a high status.

- Thought to be a friendly and helpful god, who protected children, cared for women during childbirth and helped people feel safe and happy at home.

- He was also a fierce protector, carrying knives, warding off demons and killing snakes.

- Linked with music, dance and entertainment – he was often shown as playing a musical instrument or dancing.

- Worshipped throughout Egypt – his image could be found in many homes and temples. British Museum

Four sons of Horus

Image Credit: British Museum.

“The four sons of Horus were often depicted as mummified human figures with different heads, from left to right: Imsety, Duamutef, Hapi and Qebehsenuef.

- Four ancient Egyptian gods who were believed to protect the organs of the deceased during mummification and the afterlife:

- Imsety, who protected the liver

- Duamutef, who protected the stomach

- Hapi, who protected the lungs

- Qebehsenuef, who protected the intestines.

- Often depicted as mummified human figures with different heads:

- Imsety had a human head

- Duamutef had a jackal head

- Hapi had a baboon head

- Qebehsenuef had a falcon head.

- Believed to have the power to help the deceased navigate the afterlife and protect them from harm.

- Often worshipped during the mummification process – their images were placed on canopic jars that held the organs of the deceased. British Museum

Geb

Image Credit: British Museum

“Geb depicted as a man lying on his back, with his arms and legs stretched out to represent the land.”

- God of the earth and fertility (new life).

- Often depicted as a man lying on his back, with his arms and legs stretched out to represent the land.

- Married to Nut, goddess of the sky.

- Father of many other gods and goddesses, including Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys.

- The ancient Egyptians believed that he helped to bring about a good harvest.

- Also associated with the idea of stability and balance, as he was believed to help keep the earth firmly in place and prevent chaos and disorder.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

Hapy

Image Credit: British Museum

“Hapy portrayed as a man with a large belly, representing fertility (new life) and good food. Hapy © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Thought to control the Nile river’s inundation – this is when the river floods its banks which allows crops to grow.

- Often portrayed as a man with a large belly, representing fertility (new life) and good food.

- Often shown carrying offerings of food and drink – he sometimes had lotus flowers or papyrus plants growing from his head.

- Occasionally shown as a pair of figures tying together plants which represent the two halves of Egypt – this was a symbol of unity.

- Worshipped throughout Egypt, his influence could be felt in every aspect of life that depended on the Nile river.

- Not to be confused with Hapi who is one of the four sons of Horus. British Museum

Hathor

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Hathor depicted as a woman with a headdress of cow horns and a sun disc. Hathor © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Goddess of love, joy, music and beauty – she was often linked with women, motherhood and fertility (new life).

- Often depicted in these ways:

- With the head of a cow and the body of a woman.

- As a woman with a headdress of cow horns and a sun disc.

- As a cow with a headdress of cow horns and a sun disc.

- Thought to have the power to protect against illness and danger in her role as the tame version of the goddess Sekhmet.

- Egyptian queens were often portrayed wearing the headdress of Hathor.

- Along with Isis, she was considered by the Greeks to be a version of Aphrodite (the Greek goddess of love and beauty). British Museum

Image Credit: British Museum.

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Horus depicted as a man with the head of a falcon. Horus © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- God of the sky, war and hunting.

- Also the god of kingship, he was associated with the pharaohs and was often depicted as their protector and defender.

- Often portrayed as a man with the head of a falcon, or just as a falcon.

- The son of Osiris and Isis, he defeated his uncle Seth to claim the throne of Egypt.

- Worshipped throughout Egypt, his image could be found in many temples and tombs.

- A just and fair god who protected the people of Egypt and maintained order and balance. British Museum

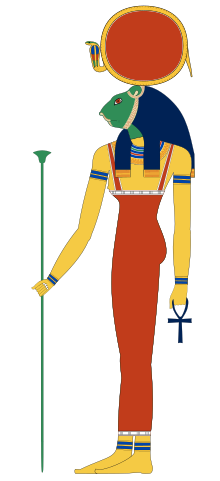

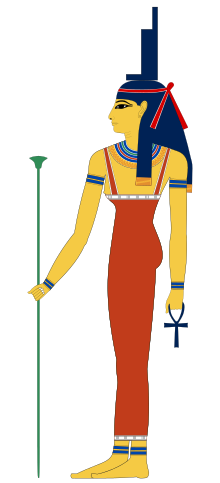

Isis

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Isis depicted as a woman with the hieroglyph for ‘throne’ worn as a crown. Isis © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Goddess of protection, motherhood and magic.

- Usually depicted as a woman with the hieroglyph for ‘throne’ worn as a crown, or with Hathor’s crown.

- The mother of Horus.

- Ancient Egyptians believed that she could perform magic and heal the sick.

- In some stories it was said that the annual Nile floods were caused by the tears of Isis, who cried for her dead husband Osiris.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above British Museum

Khepri

Image Credit: British Museum.

‘Khepri shown as a man with the head of a scarab beetle. Khepri © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.”

- Often shown as a man with the head of a scarab beetle.

- God of the rising sun – scarab beetles were often depicted rolling a ball of dung, just as the sun moves across the sky.

- Linked with transformation and rebirth, since young scarab beetles hatch from inside the ball of dung.

- A symbol of hope and resurrection and was often mentioned during funeral ceremonies. British Museum

Khnum

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Khnum depicted as a man with the head of a ram. Khnum © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Often depicted as a man with the head of a ram or a sheep.

- A creator god who was believed to form humans on a potter’s wheel using clay from the Nile river.

- Guardian of the source of the Nile river, which Egyptians believed was far away in the south.

- Often worshipped by people who would give offerings and ask for good health or a successful harvest. British Museum

Khonsu

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Khonsu depicted as a young man wrapped in a tightly-fitted garment with a crown in the shape of the moon disc. Khonsu © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- God of the moon and the son of Amun and Mut.

- Often depicted as a young man wrapped in a tightly-fitted garment, or as a man with the head of a falcon – both forms have a crown in the shape of the moon disc.

- His name means ‘traveller’ or ‘pathfinder’ perhaps in reference to how the moon travels across the sky – he was a protector of those who travelled at night.

- Often linked with healing and believed to have the power to cure illnesses and injuries.

- Thought to have the power to control time and often called on during ceremonies that marked the beginning or end of a period of time, such as a new year or the end of a king’s reign. British Museum

Ma’at

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Ma’at depicted as a woman with an ostrich feather on her head and with wings that she holds out with her hands. Ma’at © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Goddess of truth, justice and balance – and associated with order and harmony.

- Often shown as a woman with an ostrich feather on her head and with wings that she holds out with her hands.

- Believed to represent the force that kept the universe in balance, she was called on during important events such as the crowning of a pharaoh, or the signing of a peace treaty.

- Thought to have the power to protect against chaos and evil, her image was often used as a symbol of moral and ethical behaviour.

- When ancient Egyptians died they would be judged in the underworld and the heart of the deceased would be shown being weighed against Ma’at or her feather. British Museum

Montu

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Montu depicted as a man with the head of a falcon. Montu © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- A god of war, he was often worshipped by soldiers who believed he would help them win battles.

- Often depicted as a man with the head of a falcon or a bull.

- His name means ‘nomad’ or ‘traveller’ and he was associated with the desert.

- Associated with strength and vitality – some legends say he had the power to heal injuries.

- Often worshipped by people who would give him offerings and ask for his blessings, such as victory in battle or good health. British Museum

Neith

Image Credit: British Museum.

Neith shown as a woman wearing a headdress made of two bows and a shield. Neith © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- Goddess of hunting, weaving and war, she was often linked with creation and rebirth.

- Often shown as a woman wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt or a headdress made of two bows and a shield.

- She sometimes carries a bow and arrow and was said to create weapons for warriors.

- Believed to have the power to protect against danger and to help women during childbirth. British Museum

Nephthys

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Nephthys depicted as a woman wearing a headdress formed of the two hieroglyphs that spell her name. Nephthys © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Goddess of mourning, funerals and the dead.

- Often portrayed as a woman wearing a headdress formed of the two hieroglyphs that spell her name: a bowl and a house.

- Married to Seth, god of chaos.

- Along with her sister Isis, she was a protective goddess who watched over the mummified bodies of the deceased and helped guide their souls into the afterlife.

- Despite being a lesser-known goddess today, she was an important figure in ancient Egyptian mythology and was widely respected and worshipped.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

Nun

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Nun depicted as a bearded man with blue skin, representing the waters of the ocean.”

- Not part of the Ennead (the first nine ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses), he existed before the world and the gods came into being.

- The ancient Egyptians believed that before anything else existed, there was only Nun, a vast and infinite ocean of water.

- Often depicted as a bearded man with blue or green skin, representing the waters of the ocean.

- All life was believed to have emerged from Nun’s waters.

- Considered a protective god who could help keep people safe on their journeys across the ocean.

- The sun was believed to rise out of the waters of Nun every morning and sink back into them at night. British Museum

Nut

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Nut depicted as a woman with a starry body, arching over the Earth.”

- A goddess who represented the sky.

- Usually depicted as a woman with a starry body, arching over the Earth.

- Married to the god of the earth, Geb, and together they had four children: Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys.

- According to Egyptian mythology, she swallowed the sun every night and gave birth to it every morning.

- Egyptians believed that she protected and watched over the souls of the dead – they would travel through her body on their way to the afterlife, like the sun every night.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

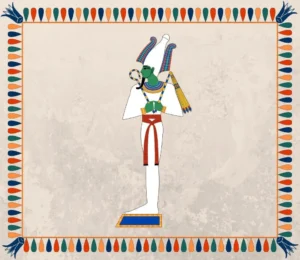

Osiris

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Osiris depicted as a mummified man with green skin, holding a crook and flail. Osiris © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- God of the afterlife and fertility (new life).

- Married to Isis and father of Horus.

- Murdered by his brother Seth, but brought back to life by Isis.

- Usually depicted as a mummified man with green or black skin, holding a crook and flail (in ancient Egypt a flail is a rod with three beaded strands attached to the top).

- Ancient Egyptians believed that he judged the souls of the dead and decided whether they were worthy of entering the afterlife.

- He was linked with the annual flooding of the Nile river, which brought new plant life – just like he was brought back to life.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

Ptah

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Ptah depicted as a mummified man wearing a skullcap and holding a sceptre. Ptah © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- God of craftsmen, architects and artists.

- Often depicted as a mummified man wearing a skullcap and holding a sceptre.

- Often associated with creation and was believed to have created the world by speaking it into existence.

- Connected with healing and believed to have the power to cure illnesses and injuries.

- The main god of the city of Memphis, one of Egypt’s earliest capitals, located near present-day Cairo. British Museum

Ra

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Ra-Horakhty and Ra are both depicted in the same way with the head of a falcon and the body of a human. Ra-Horakhty © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- A god of the sun, associated with light, warmth and growth.

- Frequently depicted with the head of a falcon and the body of a human.

- Often considered to be the first king, ruling initially over humans and gods on earth and then later in the heavens.

- Believed to have the power to control the sky and the weather, as well as life and death.

- His cult and main temple were located in a town called Heliopolis, which means ‘City of the Sun’ in Greek. British Museum

Ra-Horakhty

- God of the rising sun and often associated with light, warmth and growth.

- A combination of two other gods, Ra and Horus.

- Often depicted with the head of a hawk or falcon and the body of a human wearing a solar disc on his head – often exactly like the god Ra.

- A long hymn to Ra-Horakhty is included in one of the spells of the Book of the Dead, because the deceased wanted to be reborn like the rising sun. British Museum

Sekhmet

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Sekhmet depicted with the head of a lioness and the body of a woman. Sekhmet © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Goddess of war, destruction power and strength – her image was often used as a symbol of courage and resilience.

- Also goddess of pestilence and plague – because of this she was thought to have the power to protect against disease and evil.

- Often depicted with the head of a lioness and the body of a woman.

- A great warrior of the god Ra, she was often dispatched to fight against the enemies of the sun.

- When she was tame and calm, she changed into Bastet or Hathor. British Museum

Serqet

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Serqet depicted as a woman with a scorpion on her head. Serqet © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- Goddess of scorpions, venom and healing.

- Frequently depicted as a woman with a scorpion on her head, or holding a scorpion.

- Often associated with protection against scorpion stings and other poisonous bites, as well as rebirth.

- Because of her connection with healing, priests of Serqet were considered great magicians and doctors.

- Often worshipped by people who would give her offerings of food, drink and scorpion amulets (protective lucky charms) in exchange for her healing abilities.

- Also closely associated with protection of coffins and canopic jars in ancient Egypt – her image was often used in the decoration of tombs and funeral objects. British Museum

Seshat

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Seshat depicted as a woman wearing a headdress shaped like a seven-pointed star. Seshat © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Goddess of all types of notation, including writing, accounting, record keeping, censuses, mathematics and building planning.

- Her name literally means ‘the female scribe’.

- Often depicted as a woman wearing a headdress shaped like a seven-pointed star.

- Sometimes described as Thoth’s sister, wife, or daughter.

- She had no temple of her own, but played a part in the rituals for the laying of the foundations of all buildings. British Museum

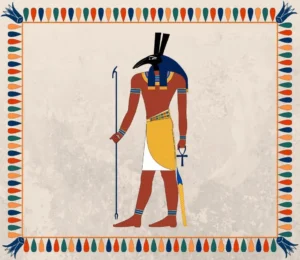

Seth

Image Credit: British Museum.

‘Seth shown with the body of a human and the head of an animal that resembles a mix of different creatures, including a jackal, donkey and aardvark. Seth © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- God of chaos, the desert, storms, violence and foreign people.

- Often shown with the head of an animal that resembled a mix of different creatures, including a jackal, donkey and aardvark.

- Portrayed as a villain who killed his brother Osiris out of jealousy, he was also seen as a protector who defended the sun god Ra from dangerous creatures.

- Due to these two roles, he was feared by many Egyptians, but worshipped by others including the kings Sety I and II, who were named after him.

- Despite his reputation, he was sometimes called upon to help crops grow and have a good harvest.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

Shu

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Shu depicted as a man with a feather on his head holding his arms aloft.”

- God of air and the atmosphere.

- Husband of Tefnut, goddess of moisture.

- Often depicted as a man with a feather on his head, holding his children apart: the goddess Nut (the sky) the god Geb (the earth).

- Sometimes connected with the sun and thought to help the sun god Ra as he journeyed across the sky each day.

- In some stories, he created the first humans by breathing life into clay or mud, making him a god of life and creation as well.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

Sobek

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Sobek depicted with the head of a crocodile and the body of a human. Sobek © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- God of the Nile river, often associated with fertility (new life), protection and strength.

- Often depicted with the head of a crocodile and the body of a human, or sometimes fully as a crocodile.

- Believed to have the power to protect people from danger, such as crocodile attacks or evil spirits.

- Often worshipped in temples located near the Nile river, which sometimes kept many sacred crocodiles in large pools.

- Some legends say that he could control the flow of the Nile river and make it flood or recede as needed. British Museum

Tawaret

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Tawaret depicted as a standing hippopotamus with the belly and breasts of a pregnant woman. Tawaret © Jeff Dahl, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

- Goddess of childbirth, fertility (new life) and protection – frequently associated with motherhood and family.

- Often portrayed as a standing hippopotamus with the belly and breasts of a pregnant woman.

- Closely linked with the protection of children – she was often depicted on furniture and household objects to ward off danger and ensure the health and wellbeing of children.

- Based on the number of amulets (protective lucky charms) and other images of her that survive today, she was one of the most popular household deities.

- She became a popular goddess outside of Egypt as well, also serving as a maternal goddess in areas of the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean and parts of Western Asia). British Museum

Tefnut

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Tefnut depicted as a woman with the head of a lioness. Tefnut © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence

- Goddess of moisture, including rain, dew, and other forms of moisture in the environment.

- Often depicted as a lioness, or as a woman with the head of a lioness.

- Believed to have the power to bring rain and moisture to the earth, helping to grow crops and support life.

- Also associated with the sun and was believed to help the sun god Ra as he journeyed across the sky each day.

- She and her husband Shu were two of the first gods created by Atum, the god of creation.

- Part of the Ennead (the first nine gods and goddesses), learn about the Ennead above. British Museum

Image Credit: British Museum.

Image Credit: British Museum.

“Thoth depicted with the head of an ibis bird and the body of a human. Thoth © Eternal Space, shared under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence”

Thoth

- God of wisdom, writing and knowledge, as well as a moon god.

- Often depicted with the head of an ibis bird and the body of a human, but he was sometimes depicted as a baboon.

- Frequently associated with scribes and scholars, as he was believed to have invented hieroglyphs, the ancient Egyptian writing system.

- Also believed to have the power to heal illnesses and injuries – he was considered a great magician.

.

Local Gods

“… the great gods of the country were known by different names in each nome or province, their ritual was distinctive, and even the legends of their origin and adventures assumed a different shape. Many of the great cities, too, possessed special gods of their own, and to these were often added the attributes of one or more of the greater and more popular forms of godhead. ..

Animism

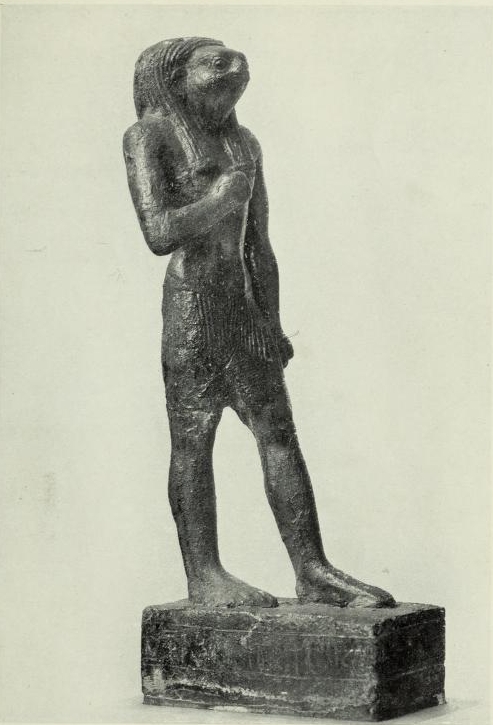

The falcon-headed Horus

Image Credit: The Met

” The Egyptian symbol for the soul (the ba) is a man-headed bird. Now the conception of the soul as a bird is a very common one among savages and barbarians of a low order. To uncultured man the bird is always incomprehensible because of its magical power of flight, its appearance in the sky where dwell the gods, and its song, approaching speech. From the bird the savage evolves the idea of the winged spirit or god, the messenger from the heavens. Thus many supernatural beings in all mythological systems are given wings. …

The Egyptian Symbol for the Soul In the British Museum

The Soul Is Depicted as a Man-Headed Bird

Creation Myth

According to the god Ra

“There are several accounts in existence which deal with the Egyptian conception of the creation of the world and of man. We find a company of eight gods alluded to in the Pyramid Texts as the original makers and moulders of the universe.

“The god Nu and his consort Nut were deities of the firmament and the rain which proceeds therefrom.

“Hehu and Hehut appear to personify fire, and

“Kekui and Kekuit the darkness which brooded over the primeval abyss of water.

“Kerh and Kerhet also appear to have personified Night or Chaos.

“Some of these gods have the heads of frogs,[6] others those of serpents, and in this connexion we are reminded of the deities which are alluded to in the story of creation recorded in the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Kiche Indians of Guatemala, two of whom, Xpiyacoc and Xmucane, are called “the ancient serpents covered with green feathers,” male and female.

“We find in the account of the creation story now under consideration the admixture of the germs of life enveloped in thick darkness, so well known to the student of mythology as symptomatic of creation myths all the world over.

“A papyrus (c. 312 B.C.) preserved in the British Museum contains a series of chapters of a[Pg 13] magical nature, the object of which is to destroy Apepi, the fiend of darkness, and in it we find two copies of the story of creation which detail the means by which the sun came into being.

.

Ra image Credit: Wikipedia

Transcript:

Join us in this video as we venture back to a time before the creation of the Great Pyramids,

prior to the construction of the elegant temples that dot the Nile’s valleys,

Here, we’ll explore the unique origins of one of Egypt’s most revered deities,

to some, the creator of all gods who harnessed the power of the universe.

This is the story of the mysterious and all-powerful Egyptian deity, Ra.

Who Was RA?

Considered a creator deity, Ra is one of the oldest and most powerful Ancient

Egyptian gods. According to legends, he is said to have been a self-created god who

formed himself from the vast nothingness during a time before the universe. Every

other deity in the Egyptian pantheon is considered a direct descendant of him.

In ancient times, Ra’s name was associated with the sun. But, as with most deities,

he had more than one name. Sometimes, he was referred to as Amun Ra, Khepri, or Atum.

Each of the individual names was associated with the various aspects

of Ra’s totality. As time passed in Egypt, new dynasties would create new names for

older deities as they assimilated them into distinct belief systems.

Ra was undoubtedly the most famous of all Egyptian deities of old.

He was the god who presided over the sun, allowing the rays to bring forth a bountiful harvest.

Ra was also considered the king of kings and the one who could bring forth order.

The god was depicted in various forms, often represented by a solar disk.

Another common depiction witnessed on hieroglyphic inscriptions, was a man with the head of a falcon.

It’s thought the worship of Ra first arose in a town known as Iunu.

To the Greeks, this was the fabled Heliopolis, otherwise known as the city of the sun god.

Today, this ancient settlement is found in a northern suburb of Cairo. But just where did

this power deity come from? And what do ancient Egyptian texts tell us about the creation of

the god of the sun? The Creation of RA

The creation myth of Ra has likely been in circulation for thousands upon thousands

of years in Egypt. Sources can be found in the Pyramids Texts, tomb wall decorations,

and other hieroglyph writings which date back to the Old Kingdom over 4000 years ago. While

there are undoubtedly various renditions of the legends, the majority begin as follows:

In the beginning, the universe was an infinite body of water known as Nun; without consciousness,

without thinking, motionless and eternal. From this vast nothingness, Ra willed himself into

existence from the chaos, becoming the firstborn god. In time, Ra decided he would create children,

so from nothing more than will and without a partner, he gave birth to Tefnut, the goddess of

moisture, and Shu, the god of air. In return, his children gave birth to the Geb, the god of earth,

and Nut, the goddess of the sky. With this, the physical universe was created.

Ra Creating the Sun, Moon, And Humanity

After the creation of Tefnut and Shu, the world was but an infinite ocean and

Ra decided that he needed light to shine on the world so he could keep an eye on his children.

But, to do so, he would have to create an eye that looks down on his children from above.

So Ra fashioned an enormous eye and sent it off to scour the earth in search of his children.

But, upon returning, the sun had discovered Ra had created a second eye in its absence.

Full of jealousy, the first eye became angry. So, to appease it, Ra gave the first more power

than the second. Thus, the first eye became the sun, and the second became the moon.

Now that the world was created, Ra continued to allow gods to multiply, and celestial bodies

began to fill the night sky. Eventually, humanity was created from the tears of Ra. As eons passed,

however, Ra became displeased with the ungrateful race of humans who walked the

earth. When he learned of the plots put in place by the humans against him, he decided that drastic

action must be taken. Ra gathered the other gods in council and they concluded that humanity must

be destroyed. So the gods sent Hathor to wipe out humanity, and she engaged in a brutal cleansing

mission that killed hundreads of thousands of humans until but a tiny remnant remained.

At this point, Ra decided no more bloodshed was necessary and allowed the remaining humans

to live in peace. However, he was thoroughly sick of the human world and decided to retreat

into the heavens, leaving the god Shu to rule over the mortal world. After Ra left the eart,

Geb and Nut married even though their creator restricted them from doing so. Ra soon found out,

and in his wrath, he ordered Shu to separate them. Shu defeated Geb in battle and permanently

separated the two. However, Nut had already fallen pregnant, and Ra decided she was forbidden to give

birth during any month of any year. Seeing her problem, she begged the god of learning, Thoth,

to help her. Thoth had a great idea and decided to gamble with the moon for extra light throughout

the year and won. This led to the addition of five full days to the Egyptian calendar, now resulting

in 365 days. On these five days, Nut gave birth to Osiris, Set, Isis, Nepthys, and Horus The Elder.

Don’t miss to watch our video: Thoth the Atlantean & The Emerald Tablets – The

Lost Knowledge. You will find it in our channel!

The Secret Name of Ra

Many eons came to pass, and Ra had stayed clear of the direction of the earth. But,

Isis, one day, decided that she would go in search of the legend of Ra’s secret name.

The gods of Egypt believed that words held power,

which is why many of them went by pseudonyms to ensure they kept their power safe.

When she finally found Ra, he was old, feeble, and a shadow of his ancient self.

As he sat upon his throne, drool ran down his chin and onto the floor below.

Seeing this, Isis collected some of his saliva and combined it with a small handful of dirt.

Using her acclaimed magic, she formed a venomous snake from this mixture.

Ra was known for being a creature of habit and walked the same route each day to survey his

incredible creation. Isis, knowing this, set a trap and let the snake loose on his trail.

As Ra walked past the snake, it latched onto him and inflicted him with a deadly bite.

Generally, Ra was immune to such attacks, but as the snake was made from his own being,

he had no immunity against it and was soon in great pain.

Following the incident, Ra called for his followers and told them he was severely wounded.

He asked if any could provide him with a cure, but no one answered, as none could give him what

he sought. After all of the others had tried and failed, Isis told Ra she could help him,

provided that he told her his true name. Sensing there was trickery at play, Ra answered:

“I am the maker of heaven and earth, I am the establisher of the mountains,

I am the creator of the waters, I am the maker of the secrets of the two horizons.

I am the light, and I am darkness, I am the maker of the hours, the creator of days.

I am the opener of festivals, I am the maker of running streams, I am the creator of living

flame. I am Khepri in the morning, Ra at noontime, and Atum in the evening”

Let us know your thoughts on today’s video in the comments section. Did you know a Ra

was the patron deity of Egypt? Had you heard of his creation story,

and just what symbolic meaning do you believe lies within this story?

If you’ve enjoyed this video and would like to see more like it centered on ancient history, be sure

to hit that subscribe button. As always, thanks for watching, and we’ll see you all next time!

“In one account the god Ra says that he took upon himself the form of Khepera, the deity who was usually credited with the creative faculty. He proceeds to say that he continued to create new things out of those which he had already made, and that they went forth from his mouth. “Heaven,” he says, “did not exist and earth had not come into being, and the things of the earth and creeping things had not come into existence in that place, and I raised them from out of Nu from a state of inactivity.” This would imply that Khepera moulded life in the universe from the matter supplied from the watery abyss of Nu. “I found no place,” says Khepera, “whereon I could stand. I worked a charm upon my own heart. I laid a foundation in Maāt. I made every form. I was one by myself. I had not emitted from myself the god Shu, and I had not spit out from myself the goddess Tefnut. There was no other being who worked with me.” The word Maāt signifies law, order, or regularity, and from the allusion to working a charm upon his heart we may take it that Khepera made use of magical skill in the creative process, or it may mean, in Scriptural phraseology, that “he took thought unto himself” to make a world.

“The god continues that from the foundation of his heart multitudes of things came into being. But the sun, the eye of Nu, was “covered up behind Shu and Tefnut,” and it was only after an indefinite period of time that these two beings, the children of Nu, were raised up from out the watery mass and brought their father’s eye along with them. In this connexion we find that the sun, as an eye, has a certain affinity with water. Thus Odin[Pg 14] pledged his eye to Mimir for a draught from the well of wisdom, and we find that sacred wells famous for the cure of blindness are often connected with legends of saints who sacrificed their own eyesight.[7] The allusion in those legends is probably to the circumstance that the sun as reflected in water has the appearance of an eye.

“Thus when Shu and Tefnut arose from the waters the eye of Nu followed them. Shu in this case may represent the daylight and Tefnut moisture. Khepera then wept copiously, and from the tears which he shed sprang men and women. The god then made another eye, which in all probability was the moon. After this he created plants and herbs, reptiles and creeping things, while from Shu and Tefnut came Geb and Nut, Osiris and Isis, Set, Nephthys and Horus at a birth. These make up the company of the great gods at Heliopolis, and this is sufficient to show that the latter part of the story at least was a priestly concoction.

The Creation According to the god Osiris

“But there was another version, obviously an account of the creation according to the worshippers of Osiris. In the beginning of this Khepera tells us at once that he is Osiris, the cause of primeval matter. This account was merely a frank usurpation of the creation legend for the behoof of the Osirian cult. Osiris in this version states that in the beginning he was entirely alone. From the inert abyss of Nu he raised a god-soul—that is, he gave the primeval abyss a soul of its own. The myth then proceeds word for word in exactly the same manner as that which deals with the creative work of Khepera. But only so far, for we find Nu in a measure identified with Khepera, and Osiris declaring that his eye, the sun, was covered over with large bushes for a long period of years. Men are then[Pg 15] made by a process similar to that described in the first legend. From these accounts we find that the ancient Egyptians believed that an eternal deity dwelling in a primeval abyss where he could find no foothold endowed the watery mass beneath him with a soul; that he created the earth by placing a charm upon his heart, otherwise from his own consciousness, and that it served him as a place to stand upon; that he produced the gods Shu and Tefnut, who in turn became the parents of the great company of gods; and that he dispersed the darkness by making the sun and moon out of his eyes. After these acts followed the almost insensible creation of men and women by the process of weeping, and the more sophisticated making of vegetation, reptiles, and stars. In all this we see the survival of a creation myth of a most primitive and barbarous type, which much more resembles the crude imaginings of the Red Man than any concept which might be presumed to have arisen from the consciousness of ‘classic’ Egypt. But it is from such unpromising material that all religious systems spring, and however strenuous the defence made in order to prove that the Egyptians differed in this respect from other races, that defence is bound in no prolonged time to be battered down by the ruthless artillery of fact.

“We have references to other deities in the Pyramid Texts, some of whom appear to be nameless. For example, in the text of Pepi I we find homage rendered to one who has four faces and who brings the storm. This would seem to be a god of wind and rain, whose countenances are set toward the four points of the compass, whence come the four winds. Indeed, the context proves this when it says: “Thou hast taken thy spear which is dear to thee, thy pointed weapon which thrusteth down riverbanks with double[Pg 16] point like the darts of Ra and a double haft like the claws of the goddess Maftet.” …

The Ba

“The ba, as has been mentioned, did not remain with the body, but took wing after death. Among primitive peoples—the aborigines of America, for instance—the soul is frequently regarded as possessing the form and attributes of a bird. The ability of the bird to make passage for itself across the great ocean of air, the incomprehensibility of its gift of flight, the mystery of its song, its connexion with ‘heaven,’ render it a being at once strange and enviable. Such freedom, argues primitive[Pg 32] man, must have the liberated soul, untrammelled by the hindering flesh. So, too, must gods and spirits be winged, and such, he hopes, will be his own condition when he has shaken off the mortal coil and rises on pinions to the heavenly mansions. Thus the Bororos of Brazil believe that the soul possesses the form of a bird. The Bilquila Indians of British Columbia think that the soul dwells in an egg in the nape of the neck, and that upon death this egg is hatched and the enclosed bird takes flight. In Bohemian folk-lore we learn that the soul is popularly conceived as a white bird. The Malays and the Battas of Sumatra also depict the immortal part of man in bird-shape, as do the Javanese and Borneans. Thus we see that the Egyptian concept is paralleled in many a distant land. But nowhere do we find the belief so strong or so persistent over a prolonged period of time as in the valley of the Nile.

“No race conferred so much importance and dignity upon the cult of the dead as the Egyptian. It is no exaggeration to say that the life of the Egyptian of the cultured class was one prolonged preparation for death. It is probableF, however, that he was, through force of custom and environment, unaware of the circumstance. It is dangerous to indulge in a universal assertion with reference to an entire nation. But if any people ever regarded life as a mere academy of preparation for eternity, it was the mysterious and fascinating race whose vast remains litter the banks of the world’s most ancient river, and frown upon the less majestic undertakings of a civilization which has usurped the theatre of their myriad wondrous deeds. …

“Scene representing the driving of a large herd of cattle on an Egyptian farm From a Tomb at Thebes, XVIIIth Dynasty Reproduced by Permission from “Wall Decorations of Egyptian Tombs,” published by the Trustees of the British Museum—

Agriculture & Harvest Festival

“Agriculture was the backbone of Egyptian wealth; the nature of the soil—rich, black mud, deposited by the Nile, which also served to irrigate it—rendered the practice of farming peculiarly simple. The intense heat, too, assisted the speedy growth of grain. Cultivation was possible almost all the year round, but usually terminated with the harvests gathered in at the end of April, from which month to June a period of slackness was afforded the farmer.

“A great variety of crops was sown, but wheat and barley were the most popular; durra, of which bread was made, lentils, peas, beans, radishes, lettuces, onions, and flax were also cultivated. Fruits were represented by the grape, pomegranate, fig, and date. Timber was scanty and, as has been said, was mostly imported. In early times it was probably more abundant, but the introduction of the camel and the goat proved its ruin, these animals stripping the bark from the trees and devouring the shoots. Wine was chiefly made in the district of Mareotis, near Alexandria, and appears to have possessed a very delicate flavour. The papyrus plant was widely cultivated from the earliest times; the stem was employed for boat-building and rope-making, as well as for writing materials.

Osiris—Photo W.A. Mansell & Co.

[Pg 63]

CHAPTER IV: THE CULT OF OSIRIS

Osiris

“One of the principal figures in the Egyptian pantheon, and one whose elements it is most difficult to disentangle, is Osiris, or As-ar. The oldest and most simple form of the name is expressed by two hieroglyphics representing a throne and an eye. These, however, cast but little light on the meaning of the name. Even the later Egyptians themselves were ignorant of its derivation, for we find that they thought it meant ‘the Strength of the Eye’—that is, the strength of the sun-god, Ra. The second syllable of the name, ar, may, however, be in some manner connected with Ra, as we shall see later. In dynastic times Osiris was regarded as god of the dead and the under-world. Indeed, he occupied the same position in that sphere as Ra did in the land of the living. We must also recollect that the realm of the under-world was the realm of night.

“The origins of Osiris are extremely obscure. We cannot glean from the texts when or where he first began to be worshipped, but that his cult is greatly more ancient than any text is certain. The earliest dynastic centres of his worship were Abydos and Mendes. He is perhaps represented on a mace-head of Narmer found at Hieraconpolis, and on a wooden plaque of the reign of Udy-mu (Den) or Hesepti, the fifth king of the First Dynasty, who is figured as dancing before him. This shows that a centre of Osiris-worship existed at Abydos during the First Dynasty. But allusions in the Pyramid Texts give us to understand that prior to this shrines had been raised to Osiris in various parts of the Nile country. As has been outlined in the chapter on the Book of the Dead,[Pg 64] Osiris dwells peaceably in the underworld with the justified, judging the souls of the departed as they appear before him. This paradise was known as Aaru, which, it is important to note, although situated in the under-world, was originally thought to be in the sky.

“Osiris is usually figured as wrapped in mummy bandages and wearing the white cone-shaped crown of the South, yet Dr. Budge says of him: “Everything which the texts of all periods record concerning him goes to show that he was an indigenous god of North-east Africa, and that his home and origin were possibly Libyan.” In any case, we may take it that Osiris was genuinely African in origin, and that he was indigenous to the soil of the Dark Continent. Brugsch and Sir Gaston Maspero both regarded him as a water-god,[1] and thought that he represented the creative and nutritive powers of the Nile stream in general, and of the inundation in particular. This theory is agreed to by Dr. Budge, but if Osiris is a god of the Nile alone, why import him from the Libyan desert, which boasts of no rivers? River-gods do not as a rule emanate from regions of sand. Before proceeding further it will be well to relate the myth of Osiris.

The Myth of Osiris

“Plutarch is our principal authority for the legend of Osiris. A complete version of the tale is not to be found in Egyptian texts, though these confirm the accounts given by the Greek writers. The following is a brief account of the myth as it is related in Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride:

“Rhea (the Egyptian Nut, the sky-goddess) was the[Pg 65] wife of Helios (Ra). She was, however, beloved by Kronos (Geb), whose affection she returned. When Ra discovered his wife’s infidelity he was wrathful indeed, and pronounced a curse upon her, saying that her child should not be born in any month or in any year. Now the curse of Ra the mighty could not be turned aside, for Ra was the chief of all the gods. In her distress Nut called upon the god Thoth (the Greek Hermes), who also loved her. Thoth knew that the curse of Ra must be fulfilled, yet by a very cunning stratagem he found a way out of the difficulty. He went to Silene, the moon-goddess, whose light rivalled that of the sun himself, and challenged her[2] to a game of tables. The stakes on both sides were high, but Silene staked some of her light, the seventieth part of each of her illuminations, and lost. Thus it came about that her light wanes and dwindles at certain periods, so that she is no longer the rival of the sun. From the light which he had won from the moon-goddess Thoth made five days which he added to the year (at that time consisting of three hundred and sixty days) in such wise that they belonged neither to the preceding nor to the following year, nor to any month. On these five days Nut was delivered of her five children. Osiris was born on the first day, Horus on the second, Set on the third, Isis on the fourth, and Nephthys on the fifth.[3] On the birth of Osiris a loud voice was heard throughout all the world saying, “The lord of all the earth is born!” A slightly different tradition relates that a certain man named Pamyles, carrying water from the temple of Ra at Thebes, heard[Pg 66] a voice commanding him to proclaim the birth of “the good and great king Osiris,” which he straightway did. For this reason the education of the young Osiris was entrusted to Pamyles. Thus, it is said, was the festival of the Pamilia instituted.

“In course of time the prophecies concerning Osiris were fulfilled, and he became a great and wise king. The land of Egypt flourished under his rule as it had never done heretofore. Like many another ‘hero-god,’ he set himself the task of civilizing his people, who at his coming were in a very barbarous condition, indulging in cannibalistic and other savage practices. He gave them a code of laws, taught them the arts of husbandry, and showed them the proper rites wherewith to worship the gods. And when he had succeeded in establishing law and order in Egypt he betook himself to distant lands to continue there his work of civilization. So gentle and good was he, and so pleasant were his methods of instilling knowledge into the minds of the barbarians, that they worshipped the very ground whereon he trod.

Set, the Enemy

“He had one bitter enemy, however, in his brother Set, the Greek Typhon. During the absence of Osiris his wife Isis ruled the country so well that the schemes of the wicked Set to take a share in its government were not allowed to mature. But on the king’s return Set fixed on a plan whereby to rid himself altogether of the king, his brother. For the accomplishment of his ends he leagued himself with Aso, the queen of Ethiopia, and seventy-two other conspirators. Then, after secretly measuring the king’s body, he caused to be made a marvellous chest, richly fashioned and adorned, which would contain exactly the body of[Pg 67] Osiris. This done, he invited his fellow-plotters and his brother the king to a great feast. Now Osiris had frequently been warned by the queen to beware of Set, but, having no evil in himself, the king feared it not in others, so he betook himself to the banquet.

“When the feast was over Set had the beautiful chest brought into the banqueting-hall, and said, as though in jest, that it should belong to him whom it would fit. [Like Cinderella and the Glass Slipper?] One after another the guests lay down in the chest, but it fitted none of them till the turn of Osiris came. Quite unsuspicious of treachery, the king laid himself down in the great receptacle. In a moment the conspirators had nailed down the lid, pouring boiling lead over it lest there should be any aperture. Then they set the coffin adrift on the Nile, at its Tanaitic mouth. These things befell, say some, in the twenty-eighth year of Osiris’ life; others say in the twenty-eighth year of his reign.

“When the news reached the ears of Isis she was sore stricken, and cut off a lock of her hair and put on mourning apparel. Knowing well that the dead cannot rest till their bodies have been buried with funeral rites, she set out to find the corpse of her husband. For a long time her search went unrewarded, though she asked every man and woman she met whether they had seen the richly decorated chest. At length it occurred to her to inquire of some children who played by the Nile, and, as it chanced, they were able to tell her that the chest had been brought to the Tanaitic mouth of the Nile by Set and his accomplices. From that time children were regarded by the Egyptians as having some special faculty of divination. [Romanticism and Wordsworth Chil is the Father of Man?]

[Pg 68]

Osiris beguiled into the Chest—Evelyn Paul.

The Tamarisk-tree

[Body of Osiris was Carried to Byblos, which was Phonecia]

“By and by the queen gained information of a more exact kind through the agency of demons, by whom she was informed that the chest had been cast up on the shore of Byblos, and flung by the waves into a tamarisk-bush, which had shot up miraculously into a magnificent tree, enclosing the coffin of Osiris in its trunk. The king of that country, Melcarthus by name, was astonished at the height and beauty of the tree, and had it cut down and a pillar made from its trunk wherewith to support the roof of his palace. Within this pillar, therefore, was hidden the chest containing the body of Osiris. Isis hastened with all speed to Byblos, where she seated herself by the side of a fountain. To none of those who approached her would she vouchsafe a word, saving only to the queen’s maidens, and these she addressed very graciously, braiding their hair and perfuming them with her breath, more fragrant than the odour of flowers. When the maidens returned to the palace the queen inquired how it came that their hair and clothes were so delightfully perfumed, whereupon they related their encounter with the beautiful stranger. Queen Astarte, or Athenais, bade that she be conducted to the palace, welcomed her graciously, and appointed her nurse to one of the young princes.

The Grief of Isis

“Isis fed the boy by giving him her finger to suck. Every night, when all had retired to rest, she would pile great logs on the fire and thrust the child among them, and, changing herself into a swallow, would twitter mournful lamentations for her dead husband. Rumours of these strange practices were brought by[Pg 69] the queen’s maidens to the ears of their mistress, who determined to see for herself whether or not there was any truth in them. So she concealed herself in the great hall, and when night came sure enough Isis barred the doors and piled logs on the fire, thrusting the child among the glowing wood. The queen rushed forward with a loud cry and rescued her boy from the flames. The goddess reproved her sternly, declaring that by her action she had deprived the young prince of immortality. Then Isis revealed her identity to the awe-stricken Athenais and told her story, begging that the pillar which supported the roof might be given to her. When her request had been granted she cut open the tree, took out the coffin containing the body of Osiris, and mourned so loudly over it that one of the young princes died of terror. Then she took the chest by sea to Egypt, being accompanied on the journey by the elder son of King Melcarthus. The child’s ultimate fate is variously recounted by several conflicting traditions. The tree which had held the body of the god was long preserved and worshipped at Byblos. [Phonecia]

“Arrived in Egypt, Isis opened the chest and wept long and sorely over the remains of her royal husband. But now she bethought herself of her son Harpocrates, or Horus the Child, whom she had left in Buto, and leaving the chest in a secret place, she set off to search for him. Meanwhile Set, while hunting by the light of the moon, discovered the richly adorned coffin and in his rage rent the body into fourteen pieces, which he scattered here and there throughout the country.

“Upon learning of this fresh outrage on the body of the god, Isis took a boat of papyrus-reeds and journeyed forth once more in search of her husband’s remains. After this crocodiles would not touch a papyrus boat, probably because they thought it contained the[Pg 70] goddess, still pursuing her weary search. Whenever Isis found a portion of the corpse she buried it and built a shrine to mark the spot. It is for this reason that there are so many tombs of Osiris in Egypt.[4]

Isis and the Baby Prince—Evelyn Paul.

The Vengeance of Horus

“By this time Horus had reached manhood, and Osiris, returning from the Duat, where he reigned as king of the dead, encouraged him to avenge the wrongs of his parents. Horus thereupon did battle with Set, the victory falling now to one, now to the other. At one time Set was taken captive by his enemy and given into the custody of Isis, but the latter, to her son’s amazement and indignation, set him at liberty. So angry was Horus that he tore the crown from his mother’s head. Thoth, however, gave her a helmet in the shape of a cow’s head. Another version states that Horus cut off his mother’s head, which Thoth, the maker of magic, stuck on again in the form of a cow’s.

“Horus and Set, it is said, still do battle with one another, yet victory has fallen to neither. When Horus shall have vanquished his enemy, Osiris will return to earth and reign once more as king in Egypt.

Sir J.G. Frazer on Osiris

“From the particulars of this myth Sir J. G. Frazer has argued[5] that Osiris was “one of those personifications of vegetation whose annual death and resurrection have been celebrated in so many lands”—that he was a god of vegetation analogous to Adonis and Attis.

“The general similarity of the myth and ritual of[Pg 71] Osiris to those of Adonis and Attis,” says Sir J.G. Frazer, “is obvious. In all three cases we see a god whose untimely and violent death is mourned by a loving goddess and annually celebrated by his worshippers. The character of Osiris as a deity of vegetation is brought out by the legend that he was the first to teach men the use of corn, and by the custom of beginning his annual festival with the tillage of the ground. He is said also to have introduced the cultivation of the vine. In one of the chambers dedicated to Osiris in the great temple of Isis at Philæ the dead body of Osiris is represented with stalks of corn springing from it, and a priest is depicted watering the stalks from a pitcher which he holds in his hand. The accompanying legend sets forth that ‘this is the form of him whom one may not name, Osiris of the mysteries, who springs from the returning waters.’ It would seem impossible to devise a more graphic way of depicting Osiris as a personification of the corn; while the inscription attached to the picture proves that this personification was the kernel of the mysteries of the god, the innermost secret that was only revealed to the initiated.

“In estimating the mythical character of Osiris, very great weight must be given to this monument. The story that his mangled remains were scattered up and down the land may be a mythical way of expressing either the sowing or the winnowing of the grain. The latter interpretation is supported by the tale that Isis placed the severed limbs of Osiris on a corn-sieve. Or the legend may be a reminiscence of the custom of slaying a human victim as a representative of the corn-spirit, and distributing his flesh or scattering his ashes over the fields to fertilize them.”

A Shrine of Osiris—(XIIth Dynasty

“But Osiris was more than a spirit of the corn; he was also a tree-spirit, and this may well have been his[Pg 72] original character, since the worship of trees is naturally older in the history of religion than the worship of the cereals. His character as a tree-spirit was represented very graphically in a ceremony described by Firmicus Maternus. A pine-tree having been cut down, the centre was hollowed out, and with the wood thus excavated an image of Osiris was made, which was then ‘buried’ in the hollow of the tree. Here, again, it is hard to imagine how the conception of a tree as tenanted by a personal being could be more plainly expressed. The image of Osiris thus made was kept for a year and then burned, exactly as was done with the image of Attis which was attached to the pine-tree. The ceremony of cutting the tree, as described by Firmicus Maternus, appears to be alluded to by Plutarch. It was probably the ritual counterpart of the mythical discovery of the body of Osiris enclosed in the erica-tree. We may conjecture that the erection of the Tatu pillar at the close of the annual festival of Osiris was identical with the ceremony described by Firmicus; it is to be noted that in the myth the erica-tree formed a pillar in the king’s house. Like the similar custom of cutting a pine-tree and fastening an image to it, in the rites of Attis, the ceremony perhaps belonged to the class of customs of which the bringing in the Maypole is among the most familiar. As to the pine-tree in particular, at Denderah the tree of Osiris is a conifer, and the coffer containing the body of Osiris is here depicted as enclosed within the tree. A pine-cone often appears on the monuments as an offering presented to Osiris, and a manuscript of the Louvre speaks of the cedar as sprung from him. The sycamore and the tamarisk are also his trees. In inscriptions he is spoken of as residing in them, and his mother Nut is frequently portrayed in a sycamore. In a sepulchre at How[Pg 73] (Diospolis Parva) a tamarisk is depicted overshadowing the coffer of Osiris; and in the series of sculptures which illustrate the mystic history of Osiris in the great temple of Isis at Philæ a tamarisk is figured with two men pouring water on it. The inscription on this last monument leaves no doubt, says Brugsch, that the verdure of the earth was believed to be connected with the verdure of the tree, and that the sculpture refers to the grave of Osiris at Philæ, of which Plutarch tells us that it was overshadowed by a methide plant, taller than any olive-tree. This sculpture, it may be observed, occurs in the same chamber in which the god is depicted as a corpse with ears of corn sprouting from him. In inscriptions he is referred to as ‘the one in the tree,’ ‘the solitary one in the acacia,’ and so forth. On the monuments he sometimes appears as a mummy covered with a tree or with plants. It accords with the character of Osiris as a tree-spirit that his worshippers were forbidden to injure fruit-trees, and with his character as a god of vegetation in general that they were not allowed to stop up wells of water, which are so important for the irrigation of hot southern lands.”

“Sir J.G. Frazer goes on to combat the theory of Lepsius that Osiris was to be identified with the sun-god Ra. Osiris, says the German scholar, was named Osiris-Ra even in the Book of the Dead, and Isis, his spouse, is often called the royal consort of Ra. This identification, Sir J.G. Frazer thinks, may have had a political significance. He admits that the myth of Osiris might express the daily appearance and disappearance of the sun, and points out that most of the writers who favour the solar theory are careful to indicate that it is the daily, and not the annual, course of the sun to which they understand the myth to apply. But, then, why, pertinently asks Sir J. G. Frazer, was[Pg 74] it celebrated by an annual ceremony? “This fact alone seems fatal to the interpretation of the myth as descriptive of sunset and sunrise. Again, though the sun may be said to die daily, in what sense can it be said to be torn in pieces?” [Seasons of Life – Ferris Wheel of Time]

Osiris the Moon God?

“Plutarch says that some of the Egyptian philosophers interpreted Osiris as the moon, “because the moon, with her humid and generative light, is favourable to the propagation of animals and the growth of plants.” Among primitive peoples the moon is regarded as a great source of moisture. Vegetation is thought to flourish beneath her pale rays, and she is understood as fostering the multiplication of the human species as well as animal and plant life.

“Sir J. G. Frazer enumerates several reasons to prove that Osiris possessed a lunar significance. Briefly these are that

he is said to have lived or reigned twenty-eight years, the mythical expression of a lunar month, and that his body is said to have been rent into fourteen pieces—”This might be interpreted as the waning moon, which appears to lose a portion of itself on each of

the fourteen days that make up the second half of the lunar month.” Typhon found the body of Osiris at the full moon; thus its dismemberment would begin with the waning of the moon.

The Departure of Isis from Byblos—Evelyn Paul

Primitive Conceptions of the Moon

“Primitive man explains the waning moon as actually dwindling, and it appears to him as if it is being broken in pieces or eaten away. The Klamath Indians of South-west Oregon allude to the moon as ‘the One Broken in Pieces,’ and the Dacotas believe that when the moon is full a horde of mice begin to nibble at one side of it until they have devoured the whole.

Festival of Osiris in Spring — which Was Harvest – Harvest Festival

“To continue Sir J.G. Frazer’s argument, he quotes Plutarch[Pg 75] to the effect that at the new moon of the month Phanemoth, which was the beginning of spring, the Egyptians celebrated what they called ‘the entry of Osiris into the moon‘; that at the ceremony called the ‘Burial of Osiris’ they made a crescent-shaped chest, “because the moon when it approaches the sun assumes the form of a crescent and vanishes”; and that once a year, at the full moon, pigs (possibly symbolical of Set, or Typhon) were sacrificed simultaneously to the moon and to Osiris. Again, in a hymn supposed to be addressed by Isis to Osiris it is said that Thoth

Placeth thy soul in the barque Maāt

In that name which is thine of god-moon.

And again:

Thou who comest to us as a child each month,

We do not cease to contemplate thee.

Thine emanation heightens the brilliancy

Of the stars of Orion in the firmament.

“In this hymn Osiris is deliberately identified with the moon.[6]

“In effect, then, Sir James Frazer’s theory regarding Osiris is that he was a vegetation or corn god, who later became identified, or confounded, with the moon. But surely it is as reasonable to suppose that it was because of his status as moon-god that he ranked as a deity of vegetation.

Lunar Worship

“A brief consideration of the circumstances connected with lunar worship might lead us to some such supposition. The sun in his status of deity requires but little explanation. The phenomena of growth are attributed to his agency at an early period of human thought, and it is probable that wind, rain, and other atmospheric manifestations are likewise credited to his[Pg 76] action, or regarded as emanations from him. Especially is this the case in tropical climates, where the rapidity of vegetable growth is such as to afford to man an absolute demonstration of the solar power. By analogy, then, that sun of the night, the moon, comes to be regarded as an agency of growth, and primitive peoples attribute to it powers in this respect almost equal to those of the sun. Again, it must be borne in mind that, for some reason still obscure, the moon is regarded as the great reservoir of magical power. The two great orbs of night and day require but little excuse for godhead. To primitive man the sun is obviously godlike, for upon him the barbarian agriculturist depends for his very existence, and there is behind him no history of an evolution from earlier forms. It is likewise with the moon-god. In the Libyan desert at night the moon is an object which dominates the entire landscape, and it is difficult to believe that its intense brilliance and all-pervading light must not have deeply impressed the wandering tribes of that region with a sense of reverence and worship. Indeed, reverence for such an object might well precede the worship of a mere corn and tree spirit, who in such surroundings could not have much scope for the manifestation of his powers. We can see, then, that this moon-god of the Neolithic Nubians, imported into a more fertile land, would speedily become identified with the powers of growth through moisture, and thus with the Nile itself.

“Osiris in his character of god of the dead affords no great difficulties of elucidation, and in this one figure we behold the junction of the ideas of the moon, moisture, the under-world, and death—in fact, all the phenomena of birth and decay.

[Pg 77]

Osiris and the Persephone Myth

“The reader cannot fail to have observed the very close resemblance between the myth of Osiris and that of Demeter and Kore, or Persephone. Indeed, some of the adventures of Isis, notably that concerning the child of the king of Byblos, are practically identical with incidents in the career of Demeter. It is highly probable that the two myths possessed a common origin. But whereas in the Greek example we find the mother searching for her child, in the Egyptian myth the wife searches for the remains of her husband. In the Greek tale we have Pluto as the husband of Persephone and the ruler of the under-world also regarded, like Osiris, as a god of grain and growth, whilst Persephone, like Isis, probably personifies the grain itself. In the Greek myth we have one male and two female principles, and in the Egyptian one male and one female. The analogy could perhaps be pressed further by the inclusion in the Egyptian version of the goddess Nephthys, who was a sister-goddess to Isis or stood to her in some such relationship. It would seem, then, as if the Hellenic myth had been sophisticated by early Egyptian influences, perhaps working through a Cretan intercommunication.

“It remains, then, to regard Osiris in the light of ruler of the underworld. To some extent this has been done in the chapter which deals with the Book of the Dead. The god of the underworld, as has been pointed out, is in nearly every instance a god of vegetable growth, and it was not because Osiris was god of the dead that he presided over fertility, but the converse. To speak more plainly, Osiris was first god of fertility, and the circumstance that he presided over the underworld was a later innovation. But it[Pg 78] was not adventitious; it was the logical outcome of his status as god of growth. [The Seasons of Life]

Another Osirian Theory

“We must also take into brief consideration his personification of Ra, whom he meets, blends with, and under whose name he nightly sails through his own dominions. This would seem like the fusion of a sun and moon myth; the myth of the sun travelling nightly beneath the earth fused with that of the moon’s nocturnal journey across the vault of heaven. A moment’s consideration will show how this fusion took place. Osiris was a moon-god. That circumstance accounts for one half of the myth; the other half is to be accounted for as follows: Ra, the sun-god, must perambulate the underworld at night if he is to appear on the fringes of the east in the morning.

“But Osiris as a lunar deity, and perhaps as the older god, as well as in his character as god of the underworld, is already occupying the orbit he must trace. The orbits of both deities are fused in one, and there would appear to be some proof of this in the fact that, in the realm of Seker, Afra (or Ra-Osiris) changes the direction of his journey from north to south to a line due east toward the mountains of sunrise. The fusion of the two myths is quite a logical one, as the moon during the night travels in the same direction as the sun has taken during the day—that is, from east to west.

Resurrection of Crops & of Man

“It will readily be seen how Osiris came to be regarded not only as god and judge of the dead, but also as symbolical of the resurrection of the body of man. Sir James Frazer lays great stress upon a picture of Osiris in which his body is shown covered with sprouting shoots of corn, and he seems to be of opinion that this is positive evidence that Osiris was a corn-god.[Pg 79] In our view the picture is simply symbolical of resurrection. The circumstance that Osiris is represented in the picture as in the recumbent position of the dead lends added weight to this supposition.

The corn-shoot is a world-wide symbol of resurrection.

In the Eleusinian mysteries a shoot of corn was shown to the neophytes as typical of physical rebirth, and a North American Indian is quoted by Loskiel, one of the Moravian Brethren, as having spoken: “We Indians shall not for ever die. Even the grains of corn we put under the earth grow up and become living things.” Among the Maya of Central America, as well as among the Mexicans, the maize-goddess has a son, the young, green, tender shoot of the maize plant, who is strongly reminiscent of Horus, the son of Osiris, and who may be taken as typical of bodily resurrection. Later the vegetation myth clustering round Osiris was metamorphosed into a theological tenet regarding human resurrection, and Osiris was believed to have been once a human being who had died and had been dismembered. His body, however, was made whole again by Isis, Anubis and Horus acting upon the instructions of Thoth. A good deal of magical ceremony appears to have been mingled with the process, and this in turn was utilized in the case of every dead Egyptian by the priests in connexion with the embalmment and burial of the dead in the hope of resurrection. Osiris, however, was regarded as the principal cause of human resurrection, and he was capable of giving life after death because he had attained to it. He was entitled ‘Eternity and Everlastingness,’ and he it was who made men and women to be born again. This conception of resurrection appears to have been in vogue in Egypt from very early times. The great authority upon Osiris is the Book of the Dead, which[Pg 80] might well be called the ‘Book of Osiris,’ and in which are recounted his daily doings and his nightly journeyings in his kingdom of the underworld.

Sekhmet – Image Credit: Wikipedia

Isis – Image Credit: Wikipedia

Isis

“Isis, or Ast, must be regarded as one of the earliest and most important conceptions of female godhead in ancient Egypt. In the dynastic period she was regarded as the feminine counterpart of Osiris, and we may take it that before the dawn of Egyptian history she occupied a similar position. The philology of the name appears to be unfathomable. No other deity has probably been worshipped for such an extent of time, for her cult did not perish with that of most other Egyptian gods, but flourished later in Greece and Rome, and is seriously carried on in Paris to-day.

“Isis was perhaps of Libyan origin, and is usually depicted in the form of a woman crowned with her name-symbol and holding in her hand a sceptre of papyrus. Her crown is surmounted by a pair of horns holding a disk, which in turn is sometimes crested by her hieroglyph, which represents a seat or throne. Sometimes also she is represented as possessing radiant and many-coloured wings, with which she stirs to life the inanimate body of Osiris.