In a recent Bible study of the book of Jeremiah, the phrase “sour grapes” came up. Many of us who have studied literature know that the concept of “sour grapes” is also part of one of Aesop’s Fables.

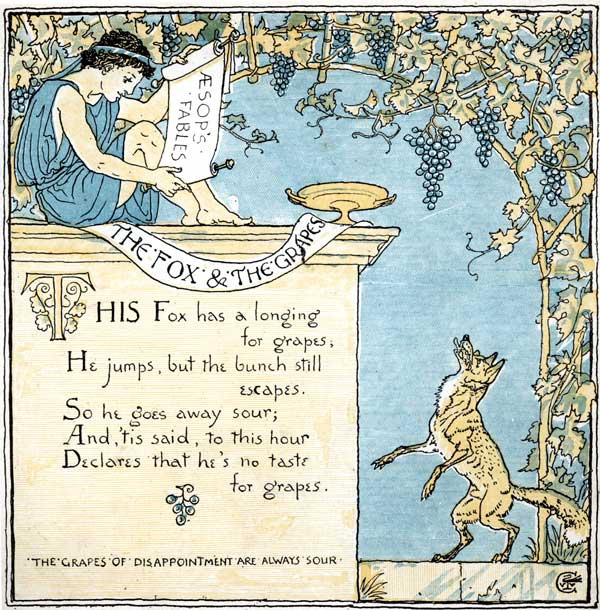

Image Credit: Walter Crane – from The Baby’s Own Aesop

Published in 1887

THE FOX AND THE GRAPES

“A Fox one day spied a beautiful bunch of ripe grapes hanging from a vine trained along the branches of a tree. The grapes seemed ready to burst with juice, and the Fox’s mouth watered as he gazed longingly at them.

“The bunch hung from a high branch, and the Fox had to jump for it. The first time he jumped he missed it by a long way. So he walked off a short distance and took a running leap at it, only to fall short once more. Again and again he tried, but in vain.

“Now he sat down and looked at the grapes in disgust.

” ‘What a fool I am I, he said. ‘Here I am wearing myself out to get a bunch of sour grapes that are not worth gaping for.’ ”

“And off he walked very, very scornfully.

“There are many who pretend to despise and belittle that which is beyond their reach”

The Aesop for Children, pg. 2.

In the book of Jeremiah, the writer also used the expression “sour grapes.” He was referencing the behavior of the Israelites who had completely revoked God’s plan for them and had become a disgruntled, angry, and sinful people.

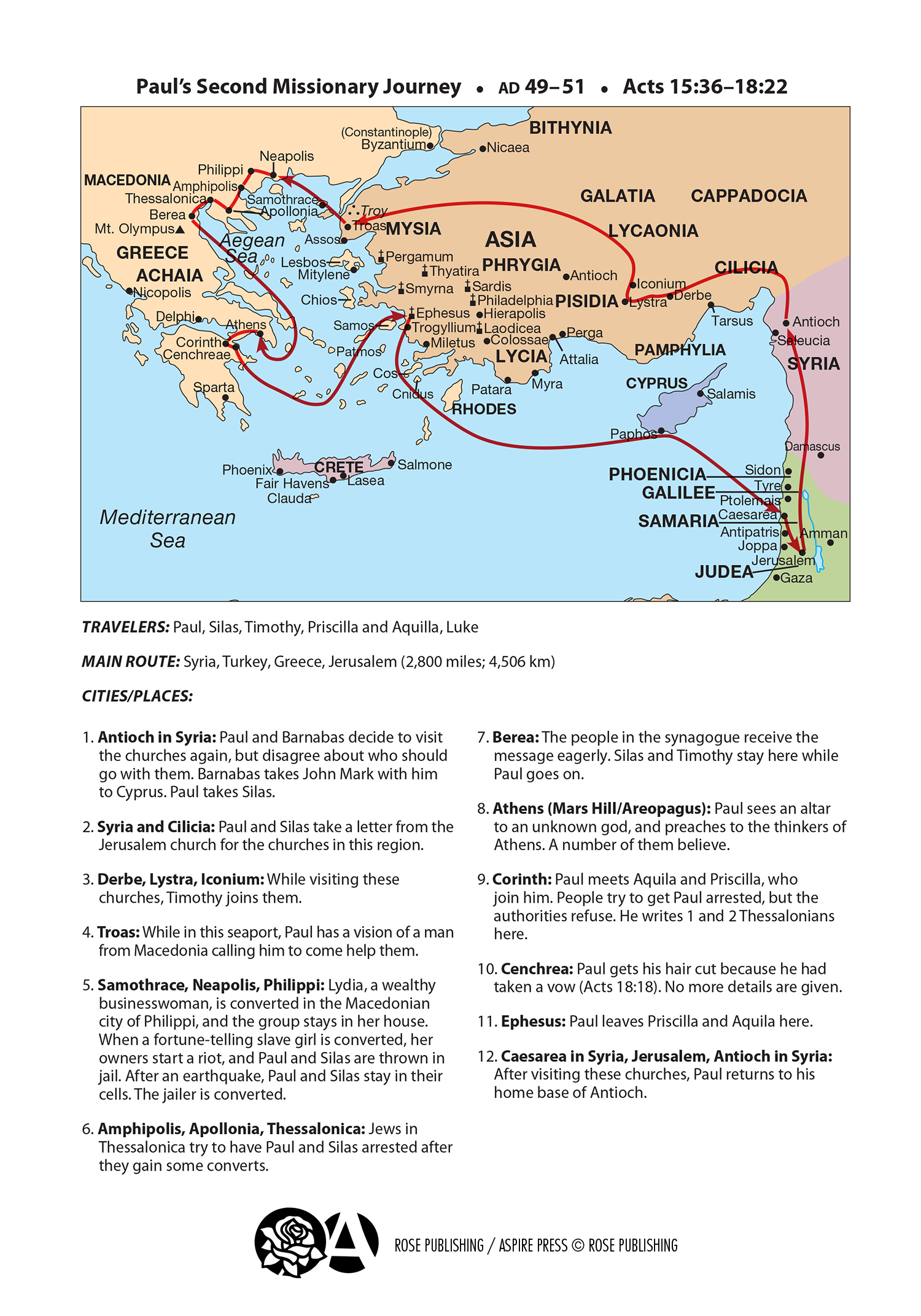

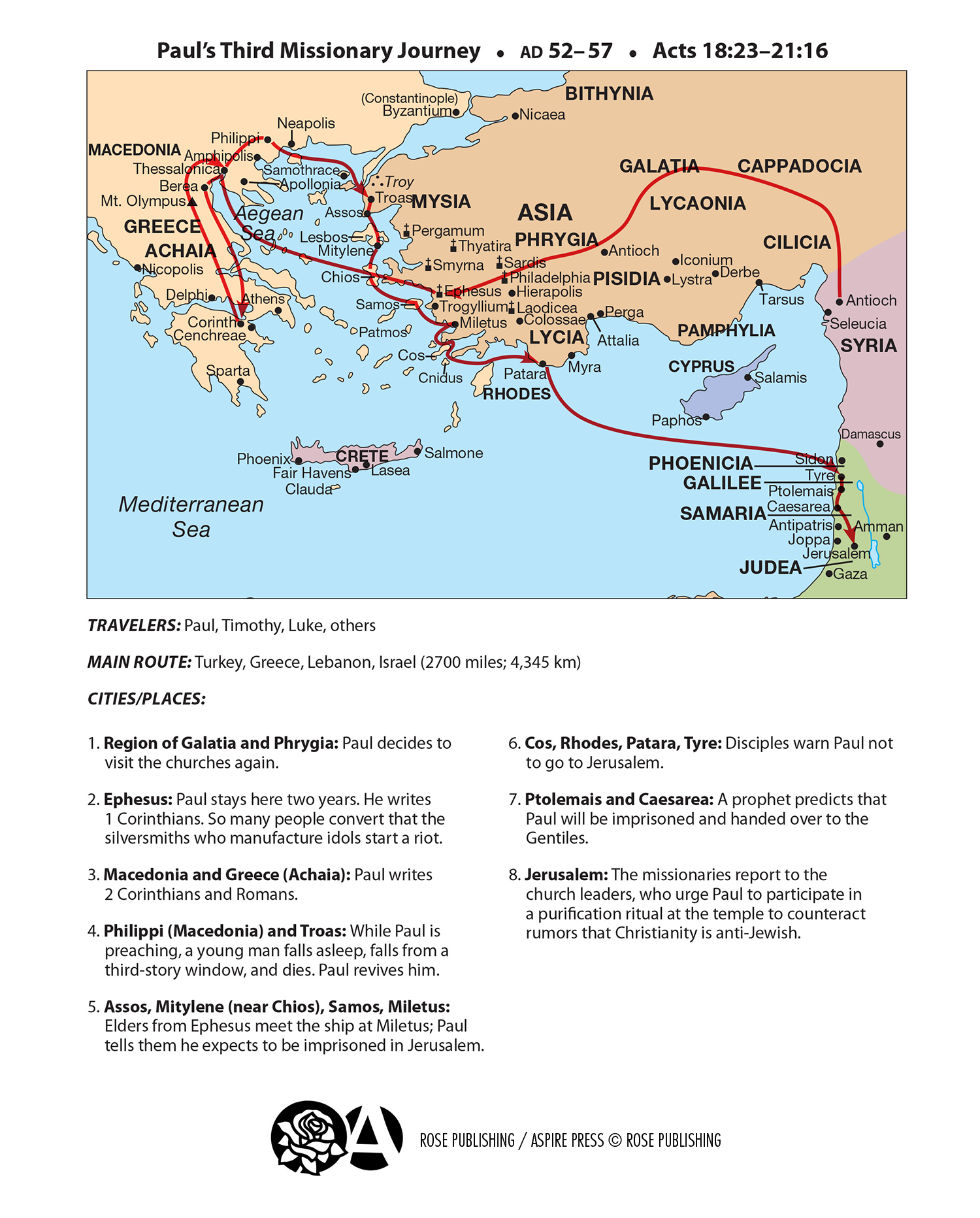

Aesop lived in Ancient Greece about 600 years before the birth of Jesus Christ, and Jeremiah lived at about the same time near Jerusalem, which is about 1400 miles from where Aesop lived. I decided to do some research to try to better understand how there might have been connections between Ancient Greece and the prophet Jeremiah, who lived a great distance from there.

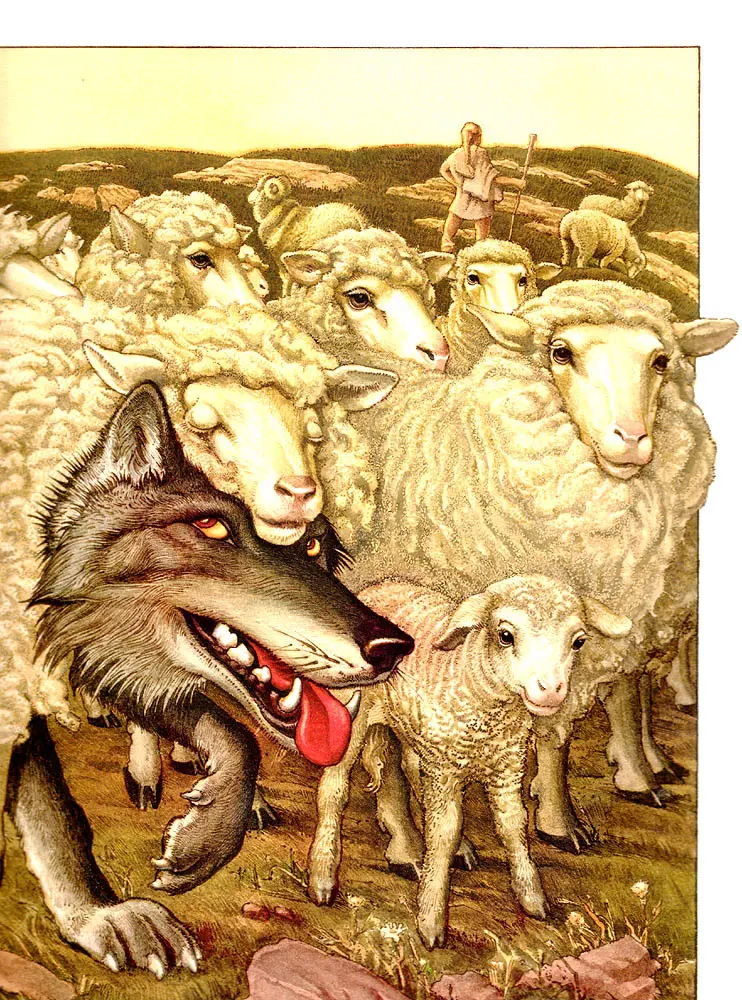

About 600 years after Aesop and Jeremiah lived, Jesus alluded to another of Aesop’s fables in his Sermon on the Mount: The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,

Illustration Credit: Charles Santore

The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

“A Wolf found great difficulty in getting at the sheep owing to the vigilance of the shepherd and his dogs. But one day it found the skin of a sheep that had been flayed and thrown aside, so it put it on over its own pelt and strolled down among the sheep. The Lamb that belonged to the sheep, whose skin the Wolf was wearing, began to follow the Wolf in the Sheep’s clothing; so, leading the Lamb a little apart, he soon made a meal off her, and for some time he succeeded in deceiving the sheep, and enjoying hearty meals.

“Appearances are deceptive.” The Fables of Aesop.

Matthew 7:15

True and False Prophets

15 “Watch out for false prophets. They come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ferocious wolves.”

Jesus lived about 600 years after Aesop, and he may or may not have been familiar with the ancient writings of the ancient Greek poet. I dare say that during Jesus’s lifetime, there was a great deal of interaction between the Greeks and the Israelites. In fact, the Bible’s New Testament was originally written in Greek, and even during the time of the Old Testament, there were interactions between Greece and the Bible lands.

“Even from the time when the oldest books of the Old Testament were written, the cultural interaction between Jews and Greeks is historically well documented. During the Hellenistic era, this coexistence was seamless. Greek was the everyday language throughout Palestine. More than one of the later books in the Old Testament were originally written in Greek. The Greek style is abundantly evident in these books. If you read the book of Job, it’s like entering the atmosphere of an ancient Greek tragedy. And the translation of the Septuagint (the 70) essentially ‘Hellenized’ the whole of the canon of the Old Testament. This alignment of Judaism and Hellenism was most pronounced in the city of Alexandria. The wise Jews of Alexandria used only Greek and cultivated only the Greek spirit and Greek philosophy. As regards the relationship between the New Testament and ancient Greek culture, there was a constant interchange, to the point that their common features cannot be separated.” Pemptousia

Ancient Greece became even more influential in the Bible lands during the reign of Alexander the Great.

Alexander the Great

“IN THE fourth century B.C.E., a young Macedonian named Alexander propelled Greece onto the world stage. In fact, he made Greece the fifth world power in Bible history and eventually came to be called Alexander the Great. The preceding empires were Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, and Medo-Persia.

“After Alexander’s death, his empire fragmented and began to wane. However, Greece’s influence by way of its culture, language, religion, and philosophy endured long after the political empire ceased.

“…the Christian Greek Scriptures, commonly called the New Testament, often refer to Greek influence. In fact, mainly in Israel there was a group of ten Hellenistic cities called the Decapolis, from a Greek word meaning “ten cities.” (Matthew 4:25; Mark 5:20; 7:31) The Bible mentions this region several times, and secular history and the impressive remains of theaters, amphitheaters, temples, and baths verify its existence.

“The Bible also makes many references to Greek culture and religion, especially in the book of Acts, which was written by the physician Luke. …

‘The temple of Artemis, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, is mentioned a number of times in the book of Acts. For example, we are told that Paul’s ministry in Ephesus angered a silversmith named Demetrius, who had a flourishing business making silver shrines of Artemis. ‘This Paul,’ said an angry Demetrius, ‘has persuaded a considerable crowd and turned them to another opinion, saying that the ones that are made by hands are not gods.’ (Acts 19:23-28) Demetrius then stirred up an angry mob, who began to shout: “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” https://www.jw.org/en/library/magazines/g201103/greece-in-bible-history/

Who Was Alexander the Great?

“Alexander the Great. Son of Philip, king of Macedon, and Olympias, an Epirote princess; born 356 B.C. Although not named in the Bible, he appears to be described prophetically in Daniel as the “goat” from the W with a notable horn between his eyes. He came against the ram with two horns, who was standing before the river, defeated the ram, and became very great until the great horn was broken and four notable ones came up from it (Dan. 8:5-8; see Daniel, book of). The prophecy identifies the ram as the kings of Media and Persia, the goat as the king of Greece, the great horn being the first king. When he fell, four kings arose in his place (8:18-22).

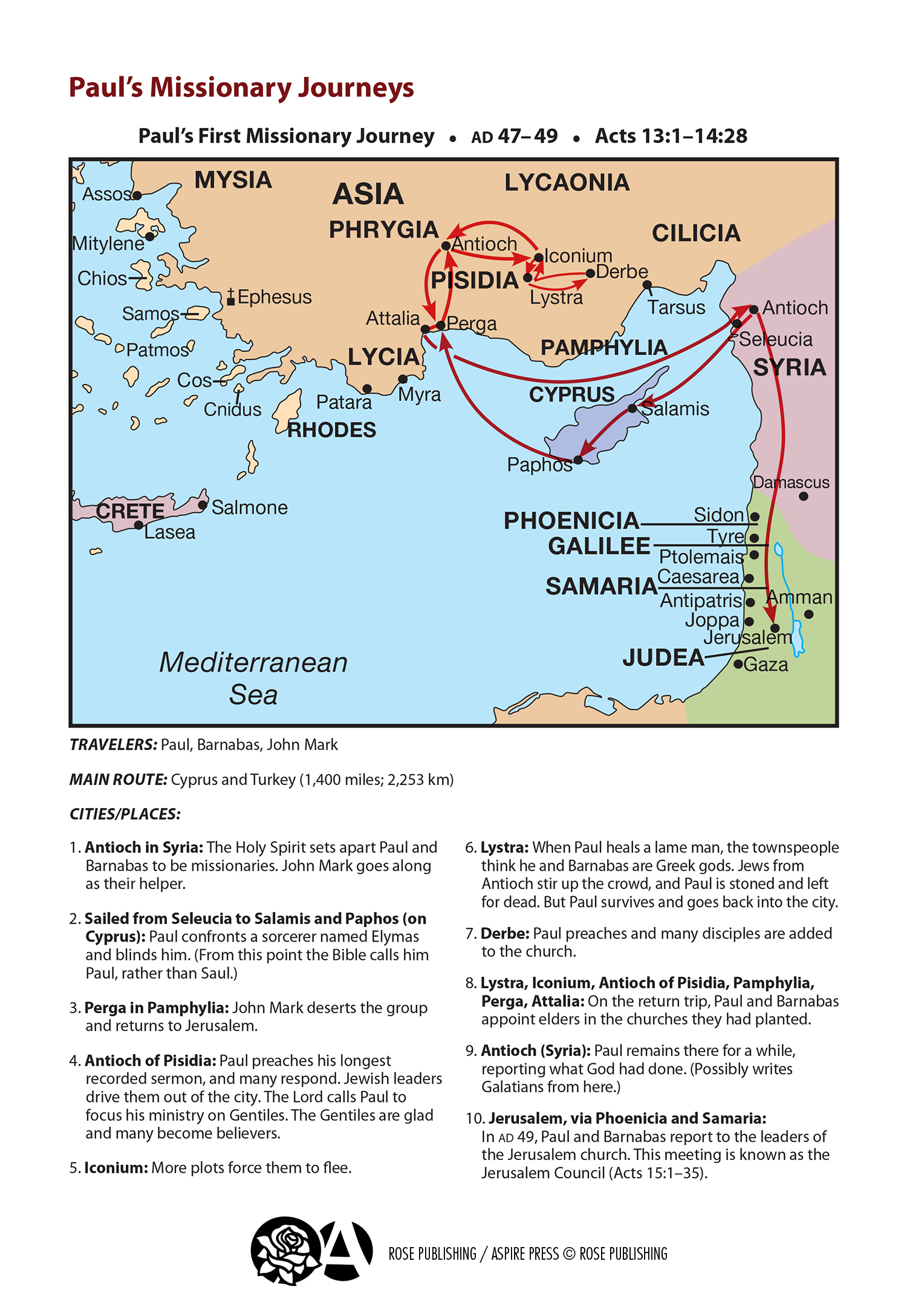

Image Credit: Zondervan

The Empire of Alexander the Great.

“The historical fulfillment is striking: Alexander led the Greek armies across the Hellespont into Asia Minor in 334 B.C. and defeated the Persian forces at the river Granicus. Moving with amazing rapidity (‘without touching the ground,’ Dan. 8:5), he again met and defeated the Persians at Issus. Turning S, he moved down the Syrian coast, advancing to Egypt, which fell to him without a blow. Turning again to the E, he met the armies of Darius for the last time, defeating them in the battle of Arbela, E of the Tigris River. Rapidly he occupied Babylon, then Susa and Persepolis, the capitals of Pers

“The next years were spent in consolidating the new empire. Alexander took Persians into his army, encouraged his soldiers to marry Asians, and began to hellenize Asia through the establishment of Greek cities in the eastern empire. He marched his armies eastward as far as India, where they won a great battle at the Hydaspes River. The army, however, refused to advance farther, and Alexander was forced to return to Persepolis. While still making plans for further conquests, he contracted a fever. Weakened by the strenuous campaign and his increasing dissipation, he was unable to throw off the fever and died in Babylon in 323 B.C. at the age of thirty-three. His empire was then divided among four of his generals. While Alexander was outstanding as a conqueror, his notable contributions to civilization came via his hellenizing efforts. The fact that Greek became the language of literature and commerce throughout the “inhabited world,” for example, was of inestimable importance to the spread of the gospel.” Zondervan

Trustworthy Prophecy

The Prophet Daniel Prophesied about Alexander the Great

“About 200 years before the time of Alexander the Great, Jehovah God’s prophet Daniel wrote concerning world domination: “Look! there was a male of the goats coming from the sunset upon the surface of the whole earth, and it was not touching the earth. And as regards the he-goat, there was a conspicuous horn between its eyes. And it kept coming all the way to the ram possessing the two horns, . . . and it came running toward it in its powerful rage. And . . . it proceeded to strike down the ram and to break its two horns, and there proved to be no power in the ram to stand before it. So it threw it to the earth and trampled it down . . . And the male of the goats, for its part, put on great airs to an extreme; but as soon as it became mighty, the great horn was broken, and there proceeded to come up conspicuously four instead of it, toward the four winds of the heavens.”—Daniel 8:5-8.

“To whom did those words apply? Daniel himself answers: “The ram that you saw possessing the two horns stands for the kings of Media and Persia. And the hairy he-goat stands for the king of Greece; and as for the great horn that was between its eyes, it stands for the first king.”—Daniel 8:20-22.

“Think about that! During the time of the Babylonian world power, the Bible foretold that the succeeding powers would be Medo-Persia and Greece. Moreover, as noted earlier, the Bible specifically stated that “as soon as it became mighty, the great horn”—Alexander—would be “broken” and would be replaced by four others, adding further that none of them would be Alexander’s posterity.—Daniel 11:4.

“That prophecy was fulfilled in detail. Alexander became king in 336 B.C.E., and within seven years he defeated the mighty Persian King Darius III. Thereafter, Alexander continued to expand his empire until his premature death in 323 B.C.E., at the age of 32. No single individual succeeded Alexander as absolute ruler, nor did any of his offspring. Rather, his four leading generals—Lysimachus, Cassander, Seleucus, and Ptolemy—“proclaimed themselves kings” and took over the empire, states the book The Hellenist

During his campaigns, Alexander also fulfilled other Bible prophecies. For example, the prophets Ezekiel and Zechariah, who lived in the seventh and sixth centuries B.C.E., foretold the destruction of the city of Tyre. (Ezekiel 26:3-5, 12; 27:32-36; Zechariah 9:3, 4) Ezekiel even wrote that her stones and dust would be placed ‘in the very midst of the water.’ ” https://www.jw.org/en/library/magazines/g201103/greece-in-bible-history/

The disciple Luke mentioned Greece several times in the book of Acts, but the apostle Paul had significant involvement with the Greeks. Paul was a contemporary of Jesus. Both Paul and Jesus Lived 600 years after the Aesop’s Fables were written,

Who Was the Apostle Paul?

“Paul. pawl (Paulos G4263, from Lat. Paulus, meaning “small”; also known by his Heb. name, Saulos G4930, hellenized form of Saoul G4910, from šāʾûl H8620, “one asked for”). A leading apostle in the early church whose ministry was principally to the Gentiles. The main biblical source for information on the life of Paul is the Acts of the apostles, with important supplemental information from Paul’s own letters. Allusions in the letters make it clear that many events in his checkered and stirring career are unrecorded (cf. 2 Cor. 11:24-28).

“I. Names. Paul’s Hebrew name was Saul, and he is always so designated in Acts until his clash with Bar-Jesus at Paphos, where Luke writes, “Then Saul, who was also called Paul…” (Acts 13:9). Thereafter in Acts he is always called Paul, the name the apostle himself uses in all his letters. As a Roman citizen he doubtless bore both names from his youth; having both a Hebrew and a Greek or Roman name was a common practice among Jews of the Dispersion. The change to the use of the Greek name was particularly appropriate when the apostle began his position of leadership in bringing the gospel to the Gentile world (cf. the order “Paul and his companions” in 13:13 instead of “Barnabas and Saul” in vv. 2 and 7).

“II. Background. Providentially, three crucial elements in the world of that day—Greek culture, Roman citizenship, and Hebrew religion—met in the apostle to the Gentiles. Paul was born near the beginning of the first century in the busy Greco-Roman city of Tarsus, located at the NE corner of the Mediterranean Sea. A noted trading center, it was known for its manufacture of goats’ hair cloth, and here the young Saul learned his trade of tentmaking (Acts 18:3). Tarsus had a famous university; although there is no evidence that Paul attended it, its influence must have made a definite impact on him, enabling him to better understand prevailing life and views in the Roman Empire. He had the further privilege of being born a Roman citizen (22:28), though how his father had come to possess the coveted status is not known (see citizenship). Proud of the distinction and advantages thus conferred on him, Paul knew how to use that citizenship as a shield against injustice from local magistrates and to enhance the status of the Christian faith. His Gentile connections greatly aided him in bridging the chasm between the Gentile and the Jew.

“But of central significance was his strong Jewish heritage, which was fundamental to all he was and became. He was never ashamed to acknowledge himself a Jew (Acts 21:39; 22:3), was justly proud of his Jewish background (2 Cor. 11:22), and retained a deep and abiding love for his compatriots (Rom. 9:1-2; 10:1). Becoming a Christian meant no conscious departure on his part from the religious hopes of his people as embodied in the OT Scriptures (Acts 24:14-16; 26:6-7). This racial affinity with the Jews enabled Paul with great profit to begin his missionary labors in each city in the synagogue, for there he had the best-prepared audience.

“Born of purest Jewish blood (Phil. 3:5), the son of a Pharisee (Acts 23:6), Saul was cradled in orthodox Judaism. At the proper age, perhaps thirteen, he was sent to Jerusalem and completed his studies under the famous Gamaliel (22:3; 26:4-5). Being a superior, zealous student (Gal. 1:14), he absorbed not only the teaching of the OT but also the rabbinical learning of the scholars. At his first appearance in Acts as “a young man” (Acts 7:58, probably around thirty years old), he was already an acknowledged leader in Judaism. His active opposition to Christianity marked him as the natural leader of the persecution that arose after the death of Stephen (7:58—8:3; 9:1-2). The persecutions described in 26:10-11 indicate his fanatical devotion to Judaism. He was convinced that Christians were heretics and that the honor of the Lord demanded their extermination (26:9). He acted in confirmed unbelief (1 Tim. 1:13).”

“III. Conversion. The persecution was doubtless repugnant to his finer inner sensitivities, but Saul did not doubt the rightness of his course. The spread of Christians to foreign cities only increased his fury against them, causing him to extend the scope of his activities. As he approached Damascus, armed with authority from the high priest, the transforming crisis in his life occurred. Only an acknowledgment of divine intervention can explain it. Repeatedly in his letters Paul refers to it as the work of divine grace and power, transforming him and commissioning him as Christ’s messenger (1 Cor. 9:16-17; 15:10; Gal. 1:15-16; Eph. 3:7-9; 1 Tim. 1:12-16). In Acts, Luke provides three accounts of this experience, and these vary according to the immediate purpose of the narrator and supplement each other. Luke’s own version (Acts 9) relates the event objectively, while the two passages in which Luke quotes Paul’s account (chs. 22 and 26) stress those aspects appropriate to the apostle’s immediate endeavor.

“When the supernatural Being arresting him identified himself as “Jesus, whom you are persecuting,” Saul at once saw the error of his way and surrendered instantaneously and completely. The three days of fasting in blindness were days of agonizing heart-searching and further dealing with the Lord. The ministry of Ananias of Damascus consummated the conversion experience, unfolded to Saul the divine commission, and opened the door to him to the Christian fellowship at Damascus. Later, in reviewing his former life, Paul clearly recognized how God had been preparing him for his future work (Gal. 1:15-16).

“IV. Early activities. The new convert at once proclaimed the deity and messiahship of Jesus in the Jewish synagogues of Damascus, truths that had seized his soul (Acts 9:20-22). Since the purpose of his coming was no secret, this action caused consternation among the Jews. Paul’s visit to Arabia, mentioned in Gal. 1:17, seems best placed between Acts 9:22 and 23, which suggests that during this period Paul was ministering in the environments of Damascus (under Nabatean rule). Many speculate, however, that Paul felt it necessary to retire to rethink his beliefs in the light of the new revelation that had come to him; if so, the apostle came out of Arabia with the essentials of his theology fixed.

After returning to Damascus, his aggressive preaching forced him to flee the murderous fury of the Jews (Acts 9:23-25; Gal. 1:17; 2 Cor. 11:32-33). Three years after his conversion Saul returned to Jerusalem with the intention of becoming acquainted with Peter (Gal. 1:18). The Jerusalem believers regarded him with cold suspicion, but with the help of Barnabas became accepted among them (Acts 9:26-28). His bold witness to the Hellenistic Jews aroused bitter hostility and cut the visit to fifteen days (Gal. 1:18). Instructed by the Lord in a vision to leave (Acts 22:17-21), he agreed to be sent home to Tarsus (9:30), where he remained in obscurity for some years. Galatians 1:21-23 indicates that he did evangelistic work there, but we have no further details. Some think that many of the events of 2 Cor. 11:24-26 must be placed here.

“After the opening of the door of the gospel to the Gentiles in the house of Cornelius, a Gentile church was soon established in Syrian Antioch. Barnabas, who had been sent to superintend the revival, saw the need for assistance, remembered Saul’s commission to the Gentiles, and brought him to Antioch. An aggressive teaching ministry “for a whole year” produced a profound impact on the city, resulting in the designation of the disciples as “Christians” (Acts 11:20-26). Informed by visiting prophets of an impending famine, the Antioch church raised a collection and sent it to the Jerusalem elders by Barnabas and Saul (11:27-30), marking Saul’s second visit to Jerusalem since his conversion. Some scholars equate this visit with that described by Paul in Gal. 2:1-10, but Acts 11-12 reveals no traces as yet of such a serious conflict in the church about circumcision as the apostle relates in Galatians.

“V. Missionary journeys. The work of Gentile foreign missions was inaugurated by the church at Antioch under the direction of the Holy spirit in the sending forth of “Barnabas and Saul” (Acts 13:1-3). What is usually known as the “first missionary journey” began apparently in the spring of A.D. 48 with work among the Jews on the island of Cyprus. Efforts at Paphos to gain the attention of the proconsul Sergius Paulus encountered the determined opposition of the sorcerer Elymas. Saul publicly exposed Elymas’s diabolical character, and the swift judgment that fell on the sorcerer caused the amazed proconsul to believe (13:4-12). It was a signal victory of the gospel.

“After the events at Paphos, Saul, henceforth called Paul in Acts, emerged as the recognized leader of the missionary party. Steps to carry the gospel to new regions were taken when the party sailed to Perga in Pamphylia on the southern shores of Asia minor. Here their attendant, John Mark, cousin of Barnabas (Col. 4:10), deserted them and returned to Jerusalem, an act that Paul regarded as unjustified (see Mark, john). Arriving at Pisidian Antioch, located in the province of Galatia, the missionaries found a ready opening in the Jewish synagogue. Paul’s address to an audience composed of Jews and God-fearing Gentiles, his first recorded address in Acts, is reported at length by Luke as representative of his synagogue ministry (Acts 13:16-41). The message made a deep impression, and the people requested that he preach again the next Sabbath. The large crowd, mainly of Gentiles, who flocked to the synagogue the following Sabbath aroused the jealousy and fierce opposition of the Jewish leaders. In consequence Paul announced a turning to the Gentiles with their message. Gentiles formed the core of the church established in Pisidian Antioch (13:42-52).

“Jewish-inspired opposition forced the missionaries to depart for Iconium, SE of Antioch, where the results were duplicated and a flourishing church begun. Compelled to flee a threatened stoning at Iconium, the missionaries crossed into the ethnographic territory of Lycaonia, still within the province of Galatia, and began work at Lystra, which was apparently without a synagogue. The healing of a congenital cripple caused a pagan attempt to offer sacrifices to the missionaries as gods in human form. Paul’s horrified protest (Acts 14:15-17), arresting the attempt, reveals his dealings with pagans who did not have the OT revelation. Timothy apparently was converted at this time. Fanatical agitators from Antioch and Iconium turned the disillusioned pagans against the missionaries, and in the uproar Paul was stoned. Dragged out of the city, the unconscious apostle was left for dead, but as the disciples stood around him, he regained consciousness, and reentered the city. The next day he was able to go on to neighboring Derbe. After a fruitful and unmolested ministry there, the missionaries retraced their steps to instruct their converts and organize them into churches with responsible leaders (14:1-23). They returned to Syrian Antioch and reported how God “had opened the door of faith to the Gentiles” (14:27). That is a summary of Paul’s message to the Gentiles: salvation is solely through faith in Christ.

Paul’s First Missionary Trip

“Paul’s plan to take the collection to Jerusalem directly from Corinth was canceled because of a plot on his life; instead he went by way of Macedonia, leaving Philippi with Luke after the Passover (Acts 20:3-6). Their church-elected travel companions waited for them at Troas, where they spent a busy and eventful night (20:7-12). Hoping to reach Jerusalem for Pentecost, Paul called the Ephesian elders to meet him at Miletus. His farewell to them is marked by tender memories, earnest instructions, and searching premonitions concerning the future (20:17-35). The journey to Jerusalem was marked by repeated warnings to Paul of what awaited him there (21:1-16). Some interpreters hold that Paul blundered in persisting on going to Jerusalem in the face of these clear warnings, thus cutting short his missionary labors. The apostle, however, apparently interpreted the warnings not as prohibitions but as tests of his willingness to suffer for the cause of his Lord and the church.” Zondervan