Told by Uncle Remus: New Stories of the Old Plantation

Author: Joel Chandler Harris

Copyright, 1903, 1904, 1905, by

JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS

Illustrator: A. B. Frost

Other Illustrations by

J. M. Condé

Frank Ver Beck

II

HOW WILEY WOLF RODE IN THE BAG

Uncle Remus soon had the wagon loaded with corn, and he and the little boy started back home. The plantation road was not a good one to begin with, and the spring rains had not improved it. Consequently there were times when Uncle Remus deemed it prudent to get out of the wagon and walk. The horses were fat and strong, to be sure, but some of the small hills were very steep, so much so that the old darky had to guide the team first to the right and then to the left in order to overcome the sheer grade. In other words, he had to see-saw as he explained to the little boy. “Drive um straight up, an’ dey fall back,” he explained, “but on de see-saw dey fergits dat deyer gwine uphill.”

All this was Dutch to the little boy, who knew[38] nothing about driving horses, but he had been well trained, and so he said, “Yes, that is so.” The last time that Uncle Remus had to vacate the driver’s seat in order to relieve the horses of his weight, he stumbled into a ditch that had been dug on the side of the road to prevent the rains from washing it into gullies. He recovered himself immediately, but not before he had startled a little rabbit, which ran on ahead of the horses for a considerable distance. Instinct came to its aid after a while, and it darted into the underbrush which grew profusely on both sides of the road.

Before the little rabbit disappeared, however, Uncle Remus had time to give utterance to a hunting halloo that aroused the echoes all around and made the little boy jump, for he was not used to this sort of thing. “I declar’ ter gracious ef it don’t put me in min’ er ol’ times—de times dey tell ’bout in de tales dat been handed down. Ef dat little rab had ’a’ been five times ez big ez he is, an’ twice ez young, I’d ’a’ thunk we’d done got back ter de days when my great-grandaddy’s[39] great-grandaddy lived. You mayn’t b’lieve me, but ef you’ll count fum de time when my great-grandaddy’s great-grandaddy wuz born’d down ter dis minnit, you’ll fin’ dat youer lookin’ back on many a long year, an’ a mighty heap er Chris’mus-come-an’-gone.

“You may think dat deze times is de bes’; well, den, you kin have um ef you’ll des gi’ me de ol’ times when de nights wuz long an’ de days short, wid plenty er wood on de fire, an’ taters an’ ashcake in de embers. Han’ um here!” Uncle Remus held out his hand as if he thought the little chap had the old times and the ashcakes and the roasted potatoes in his pocket. “Den you ain’t got um,” he went on, as the child drew away and pretended to hold his pocket tight; “you ain’t got um, an’ you can’t git um. I done been had um, but I got ter nippy-nappin’ one night, an’ some un come ’long an’ tuck um—some nigger man, I speck, kaze dey wuz a big fat ’possum mixed up wid um, an’ a heap er yuther things liable fer ter make a nigger’s mouf water. Yasser! dey tuck um right away fum me, an’ I ain’t seed um sence;[40] an’ maybe ef I wuz ter see um I wouldn’t know um.”

“Were the rabbits very large in old times?” inquired the little boy.

“Dey mought er been runts in de fambly,” replied Uncle Remus cautiously, “but fum all I kin hear fum dem what know’d, ol’ Brer Rabbit wuz a sight bigger dan any er de rabbits you see deze days.”

Uncle Remus paused to give the little boy an opportunity to make some comment, or ask such questions as occurred to him, as the other little boy had been so ready to do; but he said nothing. It seemed that his curiosity had been satisfied, and yet he wanted very much to hear a story such as Uncle Remus had been in the habit of telling his father when he was the little boy. But he had been so rigidly trained to silence in the presence of his elders that he hesitated about making his desires known.

The old negro, however, was so accustomed to anticipating the wants of children, especially those in whom he took an interest, that he knew[41] perfectly well what the little boy wanted. The child’s attitude was expectant, even if his lips refused to give form to his thoughts. This sort of thing—the old negro could give it no name—was so new to Uncle Remus that he chuckled, and presently the chuckle developed into a hearty laugh.

The little boy regarded him with surprise. “Are you laughing at me, Uncle Remus?” he inquired, after some hesitation.

“Why, honey, what put dat idee in yo’ head? What I gwineter laugh at you fer? Ef you wuz a little bigger, I might laugh at you, des ter see how you’d take it. Ef you want me ter laugh at you, you’ll hatter do some growin’.”

“Grandmother says I’m a big boy,” said the child.

“Fer yo’ age an’ size, youer right smart chunk uv a boy,” assented Uncle Remus, “but you’ll hatter be lots bigger dan what you is ’fo’ I laugh at you. No, suh; I wuz gigglin’ at de way Brer Rabbit got away wid ol’ Brer Wolf endurin’ er de time when der chillun played tergedder; an’ dat[42] little rabbit dat run ’cross de road put me in min’ un it. I bet ef I’d ’a’ been dar, I’d ’a’ done mo’ dan laugh—I’d ’a’ holler’d. Yasser, dey ain’t no two ways ’bout it—I’d ’a’ des flung back my head an’ ’a’ fetched a whoop dat you could ’a’ hearn fum here ter de big house. Dat’s what I’d ’a’ done.”

“It must have been very funny, then,” remarked the little boy.

Uncle Remus looked at the child with a serious face. Surely something must be wrong with him. And yet he was still expectant—expectant and patient. The old negro had never had dealings with such a youngster as this, and he was not in the habit of telling stories “des dry so,” as he put it; so he went at it in a new, but still a characteristic, way. “Ef yo’ pa had ’a’ been settin’ wha you settin’ he wouldn’t gi’ me no peace twel I tol’ ’im zackly what I wuz laughin’ ’bout; an’ he’d ’a’ pestered me wid his inquirements twel he foun’ out all about it. Does he pester you dat a-way, honey? Kaze ef he does, I’ll tell you de way ter fetch ’im up wid a roun’ turn; des tell ’im you gwineter tell[43] his mammy on him, an’ I bet you he won’t pester you much atter dat.”

This tickled the little boy very much. The idea of asking his grandmother to make his father stop bothering him was so new and so ridiculous that he laughed unrestrainedly.

“De minnit dat little rab jumped out’n de bushes,” Uncle Remus went on, apparently paying no attention to the child’s laughter, “it put me in min’ er de time when ol’ Brer Rabbit had a lot er chillun an’ gran’chillun pirootin’ roun’ de neighborhoods whar he live at. Dey mought ’a’ not been any gran’chillun in de bunch, but dey wuz plenty er chillun, bofe young an’ ol’.

“Brer Rabbit ’ud move sometimes des like de folks does deze days, speshually up dar in ’Lantmatantarum, whar you come fum.” The little boy smiled at this new name for Atlanta, and snuggled a little closer to Uncle Remus, for the old man had, with this one word, entered the fields that belong to childhood. “He’d move, but mos’ allers he’d take a notion fer ter come back ter his ol’ home. Sometimes he hatter move, de[44] yuther creeturs pursued atter ’im so close, but dey allers got de ragged en’ er de pursuin’, an’ dey wuz times when dey’d be right neighborly wid ’im.

“’Twuz ’bout de time dat Brer Wolf had kinder made up his min’ dat he can’t outdo Brer Rabbit, no way he kin fix it, an’ he say ter hisse’f dat he better let ’im ’lone twel he kin git ’im in a corner whar he can’t git out. So Brer Wolf, he live wid his fambly on one side de road, an’ Brer Rabbit live wid his fambly on de yuther side, not close nuff fer ter quoil ’bout de fence line, an’ yit close nuff fer der youngest chillun ter play tergedder whiles de ol’ folks wuz payin’ der Sunday calls.

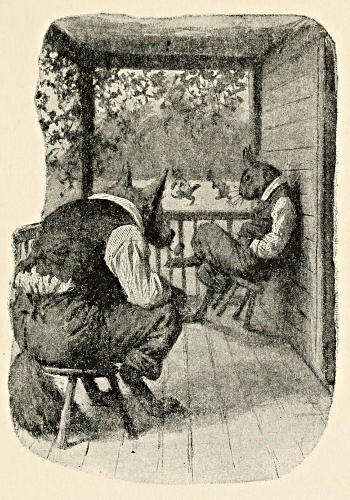

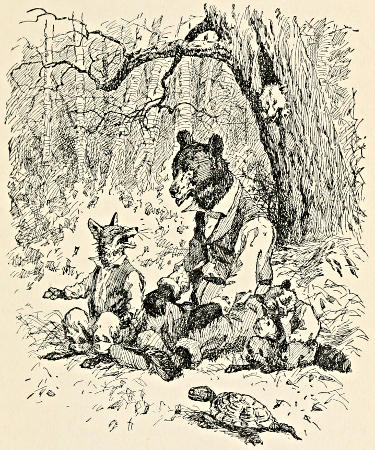

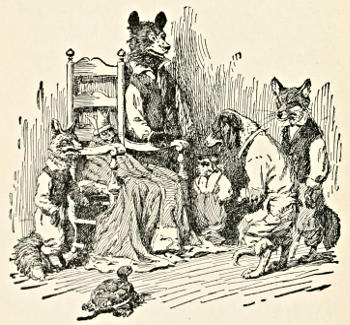

“Dey sot dar … talkin’ ’bout ol’ times”

“It went on an’ went on dis way twel it look like Brer Rabbit done fergit how ter play tricks on his neighbors an’ Brer Wolf done disremember’d dat he yever is try fer ter ketch Brer Rabbit fer meat fer his fambly. One Sunday in speshual, dey wuz mighty frien’ly. It wuz Brer Rabbit’s time fer ter call on Brer Wolf, an’ bofe un um wuz settin’ up in de porch des ez natchal ez life. Brer[45] Rabbit wuz chawin’ his terbacker an’ spittin’ over de railin’ an’ Brer Wolf wuz grinnin’ ’bout ol’ times, an’ pickin’ his toofies, which dey look mighty white an’ sharp. Dey wuz settin’ up dar, dey wuz, des ez thick ez fleas on a dog’s back, an’ lookin’ like butter won’t melt in der mouf.

“An’ whiles dey wuz settin’ dar, little Wiley Wolf an’ Riley Rabbit wuz playin’ in de yard des like chillun will. Dey run an’ dey romped, dey frisk an’ dey frolic, dey jump an’ dey hump, dey hide an’ dey slide, an’ it look like dey had mo’ fun dan a mule kin pull in a waggin. Little Wiley Wolf, he’d run atter Riley Rabbit, an’ den Riley Rabbit ’ud run atter Wiley Wolf, an’ here dey had it up an’ down an’ roun’ an’ roun’, twel it look like dey’d run deyse’f ter death. ’Bout de time you’d think dey bleeze ter drap, one un um would holler out, ‘King’s Excuse!’ an’ in dem days, when you say dat, nobody can’t ketch you, it ain’t make no diffunce who, kaze ef dey dast ter lay han’s on you atter you say dat, dey could be tuck ter de place whar dey done der judgin’, an ef dey wa’n’t mighty sharp dey’d git put in jail.

“Now, whiles Wiley Wolf an’ Riley Rabbit wuz havin’ der fun, der daddies wuz bleeze ter hear de racket what dey make, an’ see de dus’ dey raise. Dey squealed an’ dey squalled, an’ ripped aroun’ twel you’d a thunk dey wuz a good size whirlywin’ blowin’ in de yard. Brer Rabbit chaw’d his terbacker right slow an’ shot one eye, an’ ol’ Brer Wolf lick his chops an’ grin. Brer Rabbit ’low, ‘De youngsters is gittin’ mighty familious,’ an’ ol Brer Wolf say, ‘Dey is indeedy, an’ I hope dey’ll keep it up. You know how we useter be, Brer Rabbit; we wuz constant a-playin’ tricks on one an’er, an’ it lookt like we wuz allers at outs. I hope de young uns’ll have better manners!’

“Dey sot dar, dey did, talkin’ ’bout ol’ times, twel de sun got low, an’ de visitin’ had ter be cut short. Brer Rabbit say dat he had ter cut some kindlin’ so his ol’ ’oman kin git supper, an’ Brer Wolf ’low dat he allers cut his kindlin’ on Sat’day so he kin have all Sunday ter hisse’f, an’ smoke his pipe in peace. He went a piece er de way wid Brer Rabbit, an’ Wiley Wolf, he come, too, an’[47] him an’ Riley Rabbit had all sorts uv a time atter dey got in de big road. Dey wuz bushes on bofe sides, an’ dey kep’ up der game er hide an’ seek des ez fur ez Brer Wolf went, but bimeby, he say he gone fur nuff, an’ he say he hope Brer Rabbit’ll come ag’in right soon, an’ let Riley come an’ play wid Wiley endurin’ er de week.

“Not ter be outdone, Brer Rabbit invite Brer Wolf fer ter come an’ see him, an’ likewise ter let Wiley come an’ play wid Riley. ‘Dey ain’t nothin’ but chillun,’ sezee, ‘an’ look like dey done tuck a likin’ ter one an’er.’

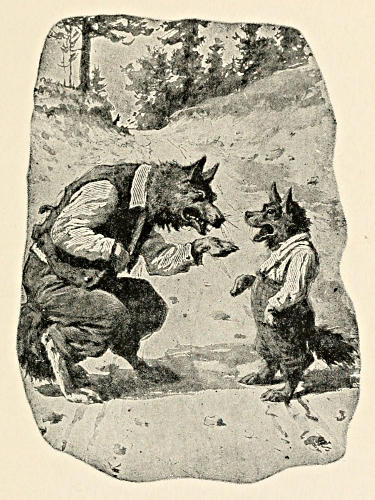

“On de way back home, Brer Wolf make a mighty strong talk ter Wiley. He say, ‘It’s mo’ dan likely dat de little Rab will come ter play wid you some day when dey ain’t nobody here, an’ when he do, I want you ter play de game er ridin’ in de bag.’ Wiley Wolf say he ain’t never hear tell er dat game, an’ ol’ Brer Wolf say it’s easy ez fallin’ off a log. ‘You git in de bag,’ sezee, ‘an’ let ’im haul you roun’ de yard, an’ den he’ll git in de bag fer you ter haul him ’roun’. What you wanter do is ter git ’im use ter de[48] bag; you hear dat, don’t you? Git ’im use ter de bag.’

“So when little Riley come, de two un um had a great time er ridin’ in de bag; ’twuz des like ridin’ in a waggin, ’ceppin’ dat Riley Rabbit look like he ain’t got no mo’ sense dan ter haul little Wiley Wolf over de roughest groun’ he kin fin’, an’ when Wiley holler’d dat he hurt ’im, Riley ’ud say he won’t do it no mo’, but de nex’ chance he got, he’d do it ag’in.

“‘Git ’im use to de bag!’”

“Well, dey had all sorts uv a time, an’ when Riley Rabbit went home, he up an’ tol’ um all what dey’d been a-playin’. Brer Rabbit ain’t say nothin’; he des sot dar, he did, an’ chaw his terbacker, an’ shot one eye. An’ when ol’ Brer Wolf come home dat night, Wiley tol’ ’im ’bout de good time dey’d had. Brer Wolf grin, he did, an’ lick his chops. He say, sezee, ‘Dey’s two parts ter dat game. When you git tired er ridin’ in de bag, you tie de bag.’ He went on, he did, an’ tol’ Wiley dat what he want ’im ter do is ter play ridin’ in de bag twel bofe got tired, an’ den play tyin’ de bag, an’ at de las’ he wuz ter tie de bag so[49] little Riley Rabbit can’t git out, an’ den ter go ter bed an’ kiver up his head.

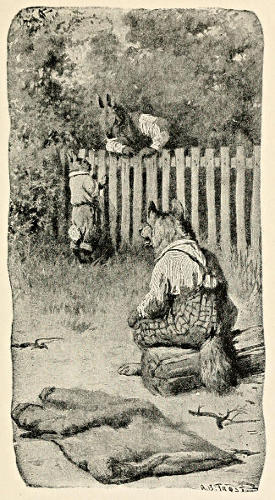

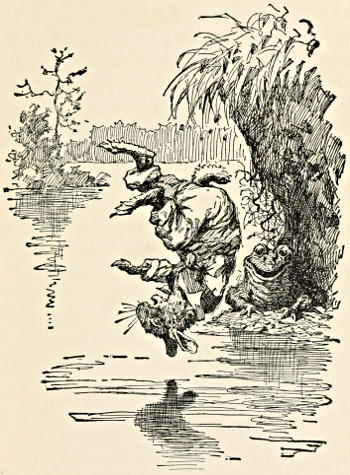

“So said, so done. Little Riley Rabbit come an’ played ridin’ in de bag, an’ den when dey got tired, dey played tyin’ de bag. ’Twuz mighty funny fer ter tie one an’er in de bag, an’ not know ef twuz gwineter be ontied. I dunner what would ’a’ happen ter little Riley Rab ef ol’ Brer Rabbit ain’t come along wid a big load er ’spicions. He call de little Rabbit ter de fence. He talk loud an’ he say dat he want ’im fer ter fetch a turn er kindlin’ when he start home, an’ den he say ter Riley, ‘Be tied in de bag once mo’, an’ den when Wiley gits in tie ’im in dar hard an’ fas’. Wet de string in yo’ mouf, an’ pull it des ez tight ez you kin. Den you come on home; yo’ mammy want you.’

“De las’ time Wiley Wolf got in de bag, little Riley tied it so tight dat he couldn’t ’a’ got it loose ef he’d ’a’ tried. He tied it tight, he did, an’ den he ’low, ‘I got ter go home fer ter git some kindlin’, an’ when I do dat, I’ll come back an’ play twel supper-time.’ But ef[50] he yever is went back dar, I ain’t never hear talk un it.”

Uncle Remus closed his eyes apparently, but not so tight that he couldn’t watch the little boy. The youngster had been listening to the story too intently to ask questions, and now he sat silent waiting for Uncle Remus to finish. He waited and waited until he grew impatient, and then he raised his head. He still waited a few moments longer, but Uncle Remus to all appearances was nodding. “Uncle Remus,” he cried, “what became of Wiley Wolf?”

“‘Den you come on home; yo’ mammy want you’”

The old negro pretended to wake with a start. “Ain’t I hear some un talkin’?” He looked all around, and then his eye fell on the little boy. “Dar you is!” he exclaimed with a laugh. “I done been ter sleep an’ drempt dat I wuz eatin’ a slishe er tater custard ez big ez de waggin body.” The little boy repeated his question, whereupon Uncle Remus held up his hands with a gesture of astonishment. “Ain’t I tol’ you dat? Den I mus’ be gittin’ ol’ an’ wobbly. De fus’ thing when I git ter de house I’m gwineter be[51] weighed fer ter see how ol’ I is. Now, whar wuz I at?”

“Wiley Wolf was in the bag,” the little boy answered.

“Ah-h-h! Right whar Riley Rab lef’ ’im. He wuz in de bag an’ dar he stayed twel ol’ Brer Wolf come fum whar he been workin’ in de fiel’—de creeturs wuz mos’ly farmers in dem days. He come back, he did, an’ he see de bag, an’ he know by de bulk un it dat dey wuz sump’n in it, an’ he ’uz so greedy dat his mouf fair dribbled. Now, den, when Wiley Wolf got in de bag, he wuz mighty tired. He’d been a-scufflin’ an a-rastlin’ twel he wuz plum’ wo’ out. He hear Riley Rab say he wuz comin’ back, an’ while he wuz waitin’, he drapt off ter sleep, an’ dar he wuz when his daddy come home—soun’ asleep.

“Ol’ Brer Wolf ain’t got but one idee, an’ dat wuz dat Riley Rab wuz in de bag, so he went ter de winder, an’ ax ef de pot wuz b’ilin’, an’ his ol’ ’oman say ’twuz. Wid dat, he pick up de bag, an’ fo’ you could bat yo’ eye, he had it soused in de pot.”

“In the boiling water!” exclaimed the child.

“Dat’s de way de tale runs,” replied Uncle Remus. “Ez dey gun it ter me, so I gin it to you.”

XII

BROTHER RABBIT AND BROTHER BULL-FROG

The day that the little boy got permission to go to mill with Uncle Remus was to be long remembered. It was a bran new experience to the city-bred child, and he enjoyed it to the utmost. It is true that Uncle Remus didn’t go to mill in the old-fashioned way, but even if the little chap had known of the old-fashioned way, his enjoyment would not have been less. Instead of throwing a bag of corn on the back of a horse, and perching himself on top in an uneasy and a precarious position, Uncle Remus placed the corn in a spring wagon, helped the little boy to climb into the seat, clucked to the horse, and went along as smoothly and as rapidly as though they were going to town.

Everything was new to the lad—the road, the scenery, the mill, and the big mill-pond, and, best[206] of all, Uncle Remus allowed him to enjoy himself in his own way when they came to the end of their journey. He was such a cautious and timid child, having little or none of the spirit of adventure that is supposed to dominate the young, that the old negro was sure he would come to no harm. Instead of wandering about, and going to places where he had no business to go, the little boy sat where he could see the water flowing over the big dam. He had never seen such a sight before, and the water seemed to him to have a personality of its own—a personality with both purpose and feeling.

The river was not a very large one, but it was large enough to be impressive when its waters fell and tumbled over the big dam. The little boy watched the tumbling water as it fell over the dam and tossed itself into foam on the rocks below; he watched it so long, and he sat so still that he was able to see things that a noisier youngster would have missed altogether. He saw a big bull-frog creep warily from the water, and wipe his mouth and eyes with one of his fore legs[207] and he saw the same frog edge himself softly toward a white butterfly that was flitting about near the edge of the stream. He saw the frog lean forward, and then the butterfly vanished. It seemed like a piece of magic. The child knew that the frog had caught the butterfly, but how? The fluttering insect was more than a foot from the frog when it disappeared, and he was sure that the frog had neither jumped nor snapped at the butterfly. What he saw, he saw as plainly as you can see your hand in the light of day.

And he saw another sight too that is not given to every one to see. While he was watching the tumbling water, and wondering where it all came from and where it was going, he thought he saw swift-moving shadows flitting from the water below up and into the mill-pond above. He never would have been able to discover just what the shadows were if one of them had not paused a moment while half-way to the top of the falling water. It poised itself for one brief instant, as a humming-bird poises over a flower, but during that fraction of time the little boy was able to see[208] that what he thought was a shadow was really a fish going from the water below to the mill-pond above. The child could hardly believe his eyes, and for a little while it seemed that the whole world was turned topsy-turvy, especially as the shadows continued to flit from the water below to the mill-pond above.

And he was still more puzzled when he reported the strange fact to Uncle Remus, for the old negro took the information as a matter of course. With him the phenomenon was almost as old as his experience. The only explanation that he could give of it was that the fish—or some kinds of fish, and he didn’t know rightly what kind it was—had a habit of falling from the bottom of the falls to the top. The most that he knew was that it was a fact, and that it was occurring every day in the year when the fish were running. It was certainly wonderful, as in fact everything would be wonderful if it were not so familiar.

“We ain’t got but one way er lookin’ at things,” remarked Uncle Remus, “an’ ef you’ll b’lieve me, honey, it’s a mighty one-sided way.[209] Ef you could git on a perch some’rs an’ see things like dey reely is, an’ not like dey seem ter us, I be boun’ you’d hol’ yo’ breff an’ shet yo’ eyes.”

The old man, without intending it, was going too deep into a deep subject for the child to follow him, and so the latter told him about the bull-frog and the butterfly. The statement seemed to call up pleasing reminiscences, for Uncle Remus laughed in a very hearty way. And when his laughing had subsided, he continued to chuckle until the little boy wondered what the source of his amusement could be. Finally he asked the old negro point blank what had caused him to laugh at such a rate.

“Yo’ pa would ’a’ know’d,” Uncle Remus replied, and then he grew solemn again and sighed heavily. For a little while he seemed to be listening to the clatter of the mill, but, finally, he turned to the little boy. “An’ so you done made de ’quaintance er ol’ Brer Bull-Frog? Is you take notice whedder he had a tail er no?”

“Why, of course he didn’t have a tail!” exclaimed the child. “Neither toad-frogs nor[210] bull-frogs have tails. I thought everybody knew that.”

“Oh, well, ef dat de way you feel ’bout um, ’tain’t no use fer ter pester wid um. It done got so now dat folks don’t b’lieve nothin’ but what dey kin see, an’ mo’ dan half un um won’t b’lieve what dey see less ’n dey kin feel un it too. But dat ain’t de way wid dem what’s ol’ ’nough fer ter know. Ef I’d ’a’ tol’ you ’bout de fishes swimmin’ ag’in fallin’ water, you wouldn’t ’a’ b’lieved me, would you? No, you wouldn’t—an’ yit, dar ’twuz right ’fo’ yo’ face an’ eyes. Dar dey wuz a-skeetin’ fum de bottom er de dam right up in de mill-pon’, an’ you settin’ dar lookin’ at um. S’posin’ you wuz ter say dat you won’t b’lieve um less’n you kin feel um; does you speck de fish gwineter hang dar in de fallin’ water an’ wait twel you kin wade ’cross de slipp’y rocks an’ put yo’ han’ on um? Did you look right close fer ter see ef de bull-frog what you seed is got a tail er no?”

The little boy admitted that he had not. He knew as well as anybody that no kind of a frog[211] has a tail, unless it is the Texas frog, which is only a horned lizard, for he saw one once in Atlanta, and it was nothing but a rusty-back lizard with a horn on his head.

“I ain’t ’sputin’ what you say, honey,” said Uncle Remus, “but de creetur what you seed mought ’a’ been a frog an’ you not know it. One thing I does know is dat in times gone by de bull-frog had a tail, kaze I hear de ol’ folks sesso, an’ mo’ dan dat, dey know’d des how he los’ it—de whar, an’ de when, an’ de which-away. Fer all I know it wuz right here at dish yer identual mill-pon’. I ain’t gwine inter court an’ make no affledave on it, but ef anybody wuz ter walk up an’ p’int der finger at me, an’ say dat dis is de place whar ol’ Brer Bull-Frog lose his tail, I’d up an’ ’low, ‘Yasser, it mus’ be de place, kaze it look might’ly like de place what I been hear tell ’bout.’ An’ den I’d shet my eyes an’ see ef I can’t git it straight in my dream.”

Uncle Remus paused, and pretended to be counting a handful of red grains of corn that he had found somewhere in the mill. Seeing that he[212] showed no disposition to tell how Brother Bull-Frog had lost his tail, the little boy reminded him of it. But the old man laughed. “Ef Brer Bull-Frog ain’t never had no tail,” he said, “how de name er goodness he gwineter lose um? Ef he yever is had a tail, why den dat’s a gray hoss uv an’er color. Dey’s a tale ’bout ’im havin’ a tail an’ losin’ it, but how kin dey be a tale when dey ain’t no tail?”

Well, the little boy didn’t know at all, and he looked so disconsolate and so confused that the old negro relented. “Now, den,” he remarked, “ef ol’ Brer Bull-Frog had a tail an’ he ain’t got none now, dey must ’a’ been sump’n happen. In dem times—de times what all deze tales tells you ’bout—Brer Bull-Frog stayed in an’ aroun’ still water des like he do now. De bad col’ dat he had in dem days, he’s got it yit—de same pop-eyes, an’ de same bal’ head. Den, ez now, dey wa’n’t a bunch er ha’r on it dat you could pull out wid a pa’r er tweezers. Ez he bellers now, des dat a-way he bellered den, mo’ speshually at night. An’ talk ’bout settin’ up late—why, ol’ Brer[213] Bull-Frog could beat dem what fust got in de habits er settin’ up late.

“De yuther creeturs can’t git no sleep”

“Dey’s one thing dat you’ll hatter gi’ ’im credit fer, an’ dat wuz keepin’ his face an’ han’s[214] clean, an’ in takin’ keer er his cloze. Nobody, not even his mammy, had ter patch his britches er tack buttons on his coat. See ’im whar you may an’ when you mought, he wuz allers lookin’ spick an’ span des like he done come right out’n a ban’-box. You know what de riddle say ’bout ’im; when he stan’ up he sets down, an’ when he walks he hops. He’d ’a’ been mighty well thunk un, ef it hadn’t but ’a’ been fer his habits. He holler so much at night dat de yuther creeturs can’t git no sleep. He’d holler an’ holler, an’ ’bout de time you think he bleeze ter be ’shame’ er hollerin’ so much, he’d up an’ holler ag’in. It got so dat de creeturs hatter go ’way off some’rs ef dey wanter git any sleep, an’ it seem like dey can’t git so fur off but what Brer Bull-Frog would wake um up time dey git ter dozin’ good.

“He’d set an’ lissen, … an’ den he’d laugh fit ter kill”

“He’d raise up an’ ’low, ‘Here I is! Here I is! Wharbouts is you? Wharbouts is you? Come along! Come along!’ It ’uz des dat a-way de whole blessed night, an’ de yuther creeturs, dey say dat it sholy was a shame dat anybody would set right flat-footed an’ ruin der good name. Look like he[215] pestered ev’ybody but ol’ Brer Rabbit, an’ de reason dat he liked it wuz kaze it worried de yuther creeturs. He’d set an’ lissen, ol’ Brer Rabbit would, an’ den he’d laugh fit ter kill kaze he ain’t a-keerin’ whedder[216] er no he git any sleep er not. Ef dey’s anybody what kin set up twel de las’ day in de mornin’ an’ not git red-eyed an’ heavy-headed, it’s ol’ Brer Rabbit. When he wanter sleep, he’d des shet one eye an’ sleep, an’ when he wanter stay ’wake, he’d des open bofe eyes, an’ dar he wuz wid all his foots under ’im, an’ a-chawin’ his terbacker same ez ef dey wa’n’t no Brer Bull-Frog in de whole Nunited State er Georgy.

“His way led ’im down todes de mill-pon’”

“It went on dis way fer I dunner how long—ol’ Brer Bull-Frog a-bellerin’ all night long an’ keepin’ de yuther creeturs ’wake, an’ Brer Rabbit a-laughin’. But, bimeby, de time come when Brer Rabbit hatter lay in some mo’ calamus root, ag’in de time when ’twould be too col’ fer ter dig it, an’ when he went fer ter hunt fer it, his way led ’im down todes de mill-pon’ whar Brer Bull-Frog live at. Dey wuz calamus root a-plenty down dar, an’ Brer Rabbit, atter lookin’ de groun’ over, promise hisse’f dat he’d fetch a basket de nex’ time he come, an’ make one trip do fer two. He ain’t been down dar long ’fo’ he had a good chance[217] fer ter hear Brer Bull-Frog at close range. He hear him, he did, an’ he shake his head an’ say dat a mighty little bit er dat music would go a long ways, kaze dey ain’t nobody what kin stan’ flat-footed an’ say dat Brer Bull-Frog is a better singer dan de mockin’-bird.

“He lissen ag’in, an’ hear Brer Bull-Frog mumblin’ an grumblin’”

“Well, whiles Brer Rabbit wuz pirootin’ roun’ fer ter see what mought be seed, he git de idee dat he kin hear thunder way off yander. He lissen ag’in, an’ he hear Brer Bull-Frog mumblin’ an’ grumblin’ ter hisse’f, an’ he must ’a’ had a mighty bad col’, kaze his talk soun’ des like a bummil-eye bee been kotch in a sugar-barrel an’ can’t git[219] out. An’ dat creetur must ’a’ know’d dat Brer Rabbit wuz down in dem neighborhoods, kaze, atter while, he ’gun to talk louder, an’ yit mo’ louder. He say, ‘Whar you gwine? Whar you gwine?’ an’ den, ‘Don’t go too fur—don’t go too fur!’ an’, atter so long a time, ‘Come back—come back! Come back soon!’ Brer Rabbit, he sot dar, he did, an’ work his nose an’ wiggle his mouf, an’ wait fer ter see what gwineter happen nex’.

“Whiles Brer Rabbit settin’ dar, Brer Bull-Frog fall ter mumblin’ ag’in an’ it look like he ’bout ter drap off ter sleep, but bimeby he talk louder, ‘Be my frien’—be my frien’! Oh, be my frien’!’ Brer Rabbit wunk one eye an’ smole a smile, kaze he done hear a heap er talk like dat. He wipe his face an’ eyes wid his pocket-hankcher, an’ sot so still dat you’d ’a’ thunk he wa’n’t nothin’ but a chunk er wood. But Brer Bull-Frog, he know’d how ter stay still hisse’f, an’ he ain’t so much ez bubble a bubble. But atter whiles, when Brer Rabbit can’t stay still no mo’, he got up fum whar he wuz settin’ at an’ mosied[220] out by de mill-race whar de grass is fresh an’ de trees is green.

“Brer Bull-Frog holla, ‘Jug-er-rum—jug-er-rum! Wade in here—I’ll gi’ you some!’ Now dey ain’t nothin’ dat ol’ Brer Rabbit like better dan a little bit er dram fer de stomach-ache, an’ his mouf ’gun ter water right den an’ dar. He went a little closer ter de mill-pon’, an’ Brer Bull-Frog keep on a-talkin’ ’bout de jug er rum, an’ what he gwine do ef Brer Rabbit will wade in dar. He look at de water, an’ it look mighty col’; he look ag’in an’ it look mighty deep. It say, ‘Lap-lap!’ an’ it look like it’s a-creepin’ higher. Brer Rabbit drawed back wid a shiver, an’ he wish mighty much dat he’d ’a’ fotch his overcoat.

“In he went—kerchug!”

“Brer Bull-Frog say, ‘Knee deep—knee deep! Wade in—wade in!’ an’ he make de water bubble des like he takin’ a dram. Den an’ dar, sump’n n’er happen, an’ how it come ter happen Brer Rabbit never kin tell; but he peeped in de pon’ fer ter see ef he kin ketch a glimp er de jug, an’ in he went—kerchug! He ain’t never know whedder he fall in, er slip in, er ef he was pushed[221] in, but dar he wuz! He come mighty nigh not gittin out; but he scramble an’ he scuffle twel he git[222] back ter de bank whar he kin clim’ out, an’ he stood dar, he did, an’ kinder shuck hisse’f, kaze he mighty glad fer ter fin’ dat he’s in de worl’ once mo’. He know’d dat a leetle mo’ an’ he’d ’a’ been gone fer good, kaze when he drapped in, er jumped in, er fell in, he wuz over his head an’ years, an’ he hatter do a sight er kickin’ an’ scufflin’ an’ swallerin’ water ’fo’ he kin git whar he kin grab de grass on de bank.

“He wonder how in de worl’ dat plain water kin be so watery”

“He sneeze an’ snoze, an’ wheeze an’ whoze, twel it look like he’d drown right whar he wuz stan’in’ any way you kin fix it. He say ter hisse’f dat he ain’t never gwineter git de tas’e er river water outer his mouf an’ nose, an’ he wonder how in de worl’ dat plain water kin be so watery. Ol’ Brer Bull-Frog, he laugh like a bull in de pastur’,[223] an’ Brer Rabbit gi’ a sidelong look dat oughter tol’ ’im ez much ez a map kin tell one er deze yer school scholars. Brer Rabbit look at ’im, but he ain’t say narry a word. He des shuck hisse’f once mo’, an’ put out fer home whar he kin set in front er de fire an’ git dry.

“Atter dat day, Brer Rabbit riz mighty soon an’ went ter bed late, an’ he watch Brer Bull-Frog so close dat dey wa’n’t nothin’ he kin do but what Brer Rabbit know ’bout it time it ’uz done; an’ one thing he know’d better dan all—he know’d dat when de winter time come Brer Bull-Frog would have ter pack up his duds an’ move over in de bog whar de water don’t git friz up. Dat much he know’d, an’ when dat time come, he laid off fer ter make Brer Bull-Frog’s journey, short ez it wuz, ez full er hap’nin’s ez de day when de ol’ cow went dry. He tuck an’ move his bed an’ board ter de big holler poplar, not fur fum de mill-pon’, an’ dar he stayed an’ keep one eye on Brer Bull-Frog bofe night an’ day. He ain’t lose no flesh whiles he waitin’, kaze he ain’t one er deze yer kin’ what mopes an’ gits sollumcolly;[224] he wuz all de time betwixt a grin an’ a giggle.

“He know’d mighty well—none better—dat time goes by turns in deze low groun’s, an’ he wait fer de day when Brer Bull-Frog gwineter move his belongin’s fum pon’ ter bog. An’ bimeby dat time come, an’ when it come, Brer Bull-Frog is done fergit off’n his mind all ’bout Brer Rabbit an’ his splashification. He rig hisse’f out in his Sunday best, an’ he look kerscrumptious ter dem what like dat kinder doin’s. He had on a little sojer hat wid green an’ white speckles all over it, an’ a long green coat, an’ satin britches, an’ a white silk wescut, an’ shoes wid silver buckles. Mo’ dan dat, he had a green umbrell, fer ter keep fum havin’ freckles, an’ his long spotted tail wuz done up in de umbrell kivver so dat it won’t drag on de groun’.”

Uncle Remus paused to see what the little boy would say to this last statement, but the child’s training prevented the asking of many questions, and so he only laughed at the idea of a frog with a tail, and the tail done up in the cover of a green[225] umbrella. The laughter of the youngster was hearty enough to satisfy the old negro, and he went on with the story.

“Whiles all dis gwine on, honey, you better b’lieve dat Brer Rabbit wa’n’t so mighty fur fum dar. When Brer Bull-Frog come out an’ start fer ter promenade ter de bog, Brer Rabbit show hisse’f an’ make like he skeered. He broke an’ run, an’ den he stop fer ter see what ’tis—an’ den he run a leetle ways an’ stop ag’in, an’ he keep on dodgin’ an’ runnin’ twel he fool Brer Bull-Frog inter b’lievin’ dat he wuz skeer’d mighty nigh ter death.

“You know how folks does when dey git de idee dat somebody’s ’fear’d un um—ef you don’t you’ll fin’ out long ’fo’ yo’ whiskers gits ter hangin’ to yo’ knees. When folks take up dis idee, dey gits biggity, an’ dey ain’t no stayin’ in de same country wid um.

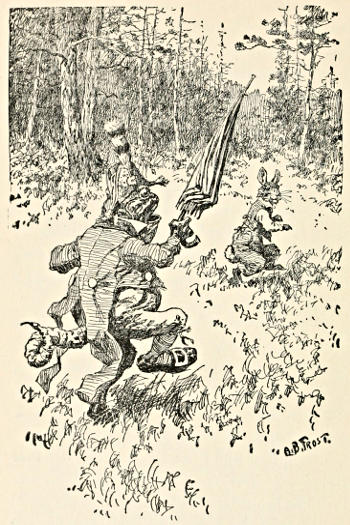

“He shuck his umbrell’ like he mad”

“Well, Brer Bull-Frog, he git de idee dat Brer Rabbit wuz ’fear’d un ’im, an’ he shuck his umbrell like he mad, an’ he beller: ‘Whar my gun?’ Brer Rabbit flung up bofe han’s like he wuz skeer’d er gittin’ a load er shot in his vitals, an’ den he broke an’ run ez hard ez he kin. Brer Bull-Frog holler out, ‘Come yer, you vilyun, an’ le’ me gi’ you de frailin’ what I done promise you!’ but ol’ Brer Rabbit, he keep on a-gwine. Brer Bull-Frog went hoppin’ atter, but he ain’t make much headway, kaze all de time he wuz hoppin’ he wuz tryin’ to strut.

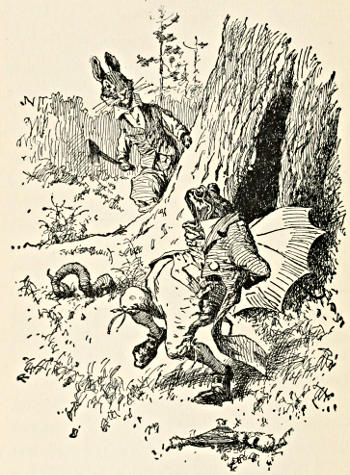

“’Twuz e’en about ez much ez Brer Rabbit kin do fer ter keep fum laughin’, but he led Brer Bull-Frog ter de holler poplar, whar he had his hatchet hid. Ez he went in, he ’low, ‘You can’t git me!’ He went in, he did, an’ out he popped on t’er side. By dat time Brer Bull-Frog wuz mighty certain an’ sho dat Brer Rabbit wuz skeer’d ez he kin be, an’ inter de holler he went, widout so much ez takin’ de trouble ter shet up his umbrell. When he got in de holler, in co’se he ain’t see hide ner ha’r er Brer Rabbit, an’ he beller out, ‘Whar is you? You may hide, but I’ll fin’ you, an’ when I does—when I does!’ He ain’t say all he wanter say, kaze by dat time Brer Rabbit wuz lammin’ on de tree wid his hatchet. He hit it some[228] mighty heavy whacks, an’ Brer Bull-Frog git de idee dat somebody wuz cuttin’ it down.

“Brer Rabbit run roun’ ter whar he wuz an’ chop his tail off”

“Dis kinder skeer’d ’im, kaze he know dat ef de tree fell while he in de holler, it’d be all-night Isom wid him. But when he make a move fer ter turn roun’ in dar fer ter come out, Brer Rabbit run roun’ ter whar he wuz, an’ chop his tail off right smick-smack-smoove.”

The veteran story-teller paused, and looked at the clouds that were gathering in the sky. “’Twouldn’t ’stonish me none,” he remarked dryly, “ef we wuz ter have some fallin’ wedder.”

“But, Uncle Remus, what happened when Brother Rabbit cut off the Bull-Frog’s tail?” inquired the little boy.

The old man sighed heavily, and looked around, as if he were hunting for some way of escape. “Why, honey, when de Frog tail wuz cut off, it stayed off, but dey tells me dat it kep’ on a wigglin’ plum twel de sun went down. Dis much I does know, dat sence dat day, none er de Frog fambly has been troubled wid tails. Ef you don’t believe me you kin ketch um an’ see.”

III

BROTHER RABBIT’S LAUGHING-PLACE

This new little boy was intensely practical. He had imagination, but it was unaccompanied by any of the ancient illusions that make the memory of childhood so delightful. Young as he was he had a contempt for those who believed in Santa Claus. He believed only in things that his mother considered valid and vital, and his training had been of such a character as to leave out all the beautiful romances of childhood.

Thus when Uncle Remus mentioned something about Brother Rabbit’s laughing-place, he pictured it forth in his mind as a sure-enough place that the four-footed creatures had found necessary for their comfort and convenience. This way of looking at things was, in some measure, a great help; it cut off long[54] explanations, and stopped many an embarrassing question.

On one occasion when the two were together, the little boy referred to Brother Rabbit’s laughing-place and talked about it in much the same way that he would have talked about Atlanta. If Uncle Remus was unprepared for such literalness he displayed no astonishment, and for all the child knew, he had talked the matter over with hundreds of other little boys.

“Uncle Remus,” said the lad, “when was the last time you went to Brother Rabbit’s laughing-place?”

“To tell you de trufe, honey, I dunno ez I ever been dar,” the old man responded.

“Now, I think that is very queer,” remarked the little boy.

Uncle Remus reflected a moment before committing himself. “I dunno ez I yever went right spang ter de place an’ put my han’ on it. I speck I could ’a’ gone dar wid mighty little trouble, but I wuz so use ter hearin’ ’bout it dat de idee er gwine dar ain’t never got in my head. It’s sorter[55] like ol’ Mr. Grissom’s house. Dey say he lives in a quare little shanty not fur fum de mill. I know right whar de shanty is, yit I ain’t never been dar, an’ I ain’t never seed it.

“It’s de same way wid Brer Rabbit’s laughin’-place. Dem what tol’ me ’bout it had likely been dar, but I ain’t never had no ’casion fer ter go dar myse’f. Yit ef I could walk fifteen er sixty mile a day, like I useter, I boun’ you I could go right now an’ put my han’ on de place. Dey wuz one time—but dat’s a tale, an’, goodness knows, you done hear nuff tales er one kin’ an’ anudder fer ter make a hoss sick—dey ain’t no two ways ’bout dat.”

Uncle Remus paused and sighed, and then closed his eyes with a groan, as though he were sadly exercised in spirit; but his eyes were not shut so tight that he could not observe the face of the child. It was a prematurely grave little face that the old man saw and whether this was the result of the youngster’s environment, or his training, or his temperament, it would have been difficult to say. But there it was, the gravity[56] that was only infrequently disturbed by laughter. Uncle Remus perhaps had seen more laughter in that little face than any one else. Occasionally the things that the child laughed at were those that would have convulsed other children, but more frequently, as it seemed, his smiles were the result of his own reflections and mental comparisons.

“I tell you what, honey,” said Uncle Remus, opening wide his eyes, “dat’s de ve’y thing you oughter have.”

“What is it?” the child inquired, though apparently he had no interest in the matter.

“What you want is a laughin’-place, whar you kin go an’ tickle yo’se’f an’ laugh whedder you wanter laugh er no. I boun’ ef you had a laughin’-place, you’d gain flesh, an’ when yo’ pa comes down fum ’Lantamatantarum, he wouldn’t skacely know you.”

“But I don’t want father not to know me,” the child answered. “If he didn’t know me, I should feel as if I were some one else.”

“Oh, he’d know you bimeby,” said Uncle Remus,[57] “an’ he’d be all de gladder fer ter see you lookin’ like somebody.”

“Do I look like nobody?” asked the little boy.

“When you fust come down here,” Uncle Remus answered, “you look like nothin’ ’tall, but sence you been ramblin’ roun’ wid me, you done ’gun ter look like somebody—mos’ like um.”

“I reckon that’s because I have a laughing-place,” said the child. “You didn’t know I had one, did you? I have one, but you are the first person in the world that I have told about it.”

“Well, suh!” Uncle Remus exclaimed with well-feigned astonishment; “an’ you been settin’ here lis’nin’ at me, an’ all de time you got a laughin’-place er yo’ own! I never would ’a’ b’lieved it uv you. Wharbouts is dish yer place?”

“It is right here where you are,” said the little boy with a winning smile.

“Honey, you don’t tell me!” exclaimed the old man, looking all around. “Ef you kin see it, you see mo’ dan I does—dey ain’t no two ways ’bout dat.”

“Why, you are my laughing-place,” cried the[58] little lad with an extraordinary burst of enthusiasm.

“Well, I thank my stars!” said Uncle Remus with emotion. “You sho’ does need ter laugh lots mo’ dan what you does. But what make you laugh at me, honey? Is my britches too big, er is I too big fer my britches? You neen’ter laugh at dis coat, kaze it’s one dat yo’ grandaddy useter have. It’s mighty nigh new, kaze I ain’t wo’d it mo’ dan ’lev’m year. It may look shiny in places, but when you see a coat look shiny, it’s a sign dat it’s des ez good ez new. You can’t laugh at my shoes, kaze I made um myse’f, an’ ef dey lack shape dat’s kaze I made um fer ter fit my rheumatism an’ my foots bofe.”

“Why, I never laughed at you!” exclaimed the child, blushing at the very idea. “I laugh at what you say, and at the stories you tell.”

“La, honey! You sho’ dunno nothin’; you oughter hearn me tell tales when I could tell um. I boun’ you’d ’a’ busted de buttons off’n yo’ whatchermacollums. Yo’ pa useter set right whar you er settin’ an’ laugh twel he can’t laugh no[59] mo’. But dem wuz laughin’ times, an’ it look like dey ain’t never comin’ back. Dat ’uz ’fo’ eve’ybody wuz rushin’ roun’ trying fer ter git money what don’t b’long ter um by good rights.”

“I was thinking to myself,” remarked the child, “that if Brother Rabbit had a laughing-place I had a better one.”

“Honey, hush!” exclaimed Uncle Remus with a laugh. “You’ll have me gwine roun’ here wid my head in de a’r, an’ feelin’ so biggity dat I won’t look at my own se’f in de lookin’-glass. I ain’t too ol’ fer dat kinder talk ter sp’ile me.”

“Didn’t you say there was a tale about Brother Rabbit’s laughing-place?” inquired the little boy, when Uncle Remus ceased to admire himself.

“I dunner whedder you kin call it a tale,” replied the old man. “It’s mighty funny ’bout tales,” he went on. “Tell um ez you may an’ whence you may, some’ll say tain’t no tale, an’ den ag’in some’ll say dat it’s a fine tale. Dey ain’t no tellin’. Dat de reason I don’t like ter tell no tale ter grown folks, speshually ef dey er white[60] folks. Dey’ll take it an’ put it by de side er some yuther tale what dey got in der min’ an’ dey’ll take on dat slonchidickler grin what allers say, ‘Go way, nigger man! You dunner what a tale is!’ An’ I don’t—I’ll say dat much fer ter keep some un else fum sayin’ it.

“Now, ’bout dat laughin’-place—it seem like dat one time de creeturs got ter ’sputin’ ’mongs’ deyselves ez ter which un kin laugh de loudest. One word fotch on an’er twel it look like dey wuz gwineter be a free fight, a rumpus an’ a riot. Dey show’d der claws an’ tushes, an’ shuck der horns, an’ rattle der hoof. Dey had der bristles up, an’ it look like der eyes wuz runnin’ blood, dey got so red.

“Des ’bout de time when it look like you can’t keep um ’part, little Miss Squinch Owl flew’d up a tree an’ ’low, ‘You all dunner what laughin’ is—ha-ha-ha-ha! You can’t laugh when you try ter laugh—ha-ha-ha-haha!’ De creeturs wuz ’stonisht. Here wuz a little fowl not much bigger dan a jay-bird laughin’ herse’f blin’ when dey wa’n’t a thing in de roun’ worl’ fer ter laugh at.[61] Dey stop der quoilin’ atter dat an’ look at one an’er. Brer Bull say, ‘Is anybody ever hear de beat er dat? Who mought de lady be?’ Dey all say dey dunno, an’ dey got a mighty good reason fer der sesso, kaze Miss Squinch Owl, she flies at night wid de bats an’ de Betsey Bugs.

“Well, dey quit der quoilin’, de creeturs did, but dey still had der ’spute; de comin’ er Miss Squinch Owl ain’t settle dat. So dey ’gree dat dey’d meet some’rs when de wedder got better, an’ try der han’ at laughin’ fer ter see which un kin outdo de yuther.” Observing that the little boy was laughing very heartily, Uncle Remus paused long enough to inquire what had hit him on his funny-bone.

“I was laughing because you said the animals were going to meet an’ try their hand at laughing,” replied the lad when he could get breath enough to talk.

Uncle Remus regarded the child with a benevolent smile of admiration. “Youer long ways ahead er me—you sho’ is. Dey ain’t na’er n’er chap in de worl’ what’d ’a’ cotch on so quick.[62] You put me in min’ er de peerch, what grab de bait ’fo’ it hit de water. Well, dat’s what de creeturs done. Dey say dey wuz gwineter make trial fer ter see which un is de out-laughin’est er de whole caboodle, an’ dey name de day, an’ all prommus fer ter be dar, ceppin’ Brer Rabbit, an’ he ’low dat he kin laugh well nuff fer ter suit hisse’f an’ his fambly, ’sides dat, he don’t keer ’bout laughin’ less’n dey’s sump’n fer ter laugh at. De yuther creeturs dey beg ’im fer ter come, but he shake his head an’ wiggle his mustache, an’ say dat when he wanter laugh, he got a laughin’-place fer ter go ter, whar he won’t be pestered by de balance er creation. He say he kin go dar an’ laugh his fill, an’ den go on ’bout his business, ef he got any business, an’ ef he ain’t got none, he kin go ter play.

“‘Gracious me!’ an’ den he howl”

“De yuther creeturs ain’t know what ter make er all dis, an’ dey wonder an’ wonder how Brer Rabbit kin have a laughin’-place an’ dey ain’t got none. When dey ax ’im ’bout it, he ’spon’, he did, dat he speck ’twuz des de diffunce ’twix one creetur an’ an’er. He ax um fer ter look at folks,[63] how diffunt dey wuz, let ’lone de creeturs. One man ’d be rich an’ an’er man po’, an’ he ax how come dat.

“Well, suh, dey des natchally can’t tell ’im what make de diffunce ’twix folks no mo’ dan dey kin tell ’im de diffunce ’twix’ de creeturs. Dey wuz stumped; dey done fergit all ’bout de trial what wuz ter come off, but Brer Rabbit fotch um back ter it. He say dey ain’t no needs fer ter see which kin outdo all de balance un um in de laughin’ business, kaze anybody what got any sense know dat de donkey is a natchal laugher, same as Brer Coon is a natchal pacer.

“Brer B’ar look at Brer Wolf, an’ Brer Wolf look at Brer Fox, an’ den dey all look at one an’er. Brer Bull, he say, ‘Well, well, well!’ an’ den he groan; Brer B’ar say, ‘Who’d ’a’[64] thunk it?’ an’ den he growl; an’ Brer Wolf say ‘Gracious me!’ an’ den he howl. Atter dat, dey ain’t say much, kaze dey ain’t much fer ter say. Dey des stan’ roun’ an’ look kinder sheepish. Dey ain’t ’spute wid Brer Rabbit, dough dey’d ’a’ like ter ’a’ done it, but dey sot about an’ make marks in de san’ des like you see folks do when deyer tryin’ fer ter git der thinkin’ machine ter work.

“Brer Rabbit he put his han’ ter his head”

“Well, suh, dar dey sot an’ dar dey stood. Dey ax Brer Rabbit how he know how ter fin’ his laughin’-place, an’ how he know it wuz a laughin’-place atter he got dar. He tap hisse’f on de head, he did, an’ ’low dat dey wuz a heap mo’ und’ his hat dan what you could git out wid a fine-toof comb. Den dey ax ef dey kin see his laughin’-place, an’ he say he’d take de idee ter bed wid ’im, an’ study ’pon it, but he kin say dis much right den, dat if he did let um[65] see it, dey’d hatter go dar one at a time, an’ dey’d hatter do des like he say; ef dey don’t dey’ll git de notion dat it’s a cryin’-place.

“Dey ’gree ter dis, de creeturs did, an’ den Brer Rabbit say dat while deyer all der tergedder, dey better choosen ’mongs’ deyse’f which un uv um wuz gwine fus’, an’ he’d choosen de res’ when de time come. Dey jowered an’ jowered, an’ bimeby, dey hatter leave it all ter Brer Rabbit. Brer Rabbit, he put his han’ ter his head, an’ shot his eyeballs an’ do like he studyin’. He say ‘De mo’ I think ’bout who shill be de fus’ one, de mo’ I git de idee dat it oughter be Brer Fox. He been here long ez anybody, an’ he’s purty well thunk uv by de neighbors—I ain’t never hear nobody breave a breff ag’in ’im.’

“Dey all say dat dey had Brer Fox in min’ all de time, but somehow dey can’t come right out wid his name, an’ dey vow dat ef dey had ’greed on somebody, dat somebody would sho’ ’a’ been Brer Fox. Den, atter dat, ’twuz all plain sailin’. Brer Rabbit say he’d meet Brer Fox at sech an’ sech a place, at sech an’ sech a time, an’ atter dat[66] dey wa’n’t no mo’ ter be said. De creeturs all went ter de place whar dey live at, an’ done des like dey allers done.

“De creeturs all went ter de place whar dey live at”

“Brer Rabbit make a soon start fer ter go ter de p’int whar he prommus ter met Brer Fox, but soon ez he wuz, Brer Fox wuz dar befo’ ’im. It seem like he wuz so much in de habits er bein’ outdone by Brer Rabbit dat he can’t do widout it. Brer Rabbit bow, he did, an’ pass de time er day[67] wid Brer Fox, an’ ax ’im how his fambly wuz. Brer Fox say dey wuz peart ez kin be, an’ den he ’low dat he ready an’ a-waitin’ fer ter go an’ see dat great laughin’-place what Brer Rabbit been talkin’ ’bout.

“Brer Rabbit say dat suit him ter a gnat’s heel, an’ off dey put. Bimeby dey come ter one er deze here cle’r places dat you sometimes see in de middle uv a pine thicket. You may ax yo’se’f how[68] come dey don’t no trees grow dar when dey’s trees all round, but you ain’t gwineter git no answer, an’ needer is dey anybody what kin tell you. Dey got dar, dey did, an’ den Brer Rabbit make a halt. Brer Fox ’low, ‘Is dis de place? I don’t feel no mo’ like laughin’ now dan I did ’fo’ I come.’

“But soon ez he wuz, Brer Fox wuz dar befo’ ’im”

“Brer Rabbit, he say, ‘Des keep yo’ jacket on, Brer Fox; ef you git in too big a hurry it might come off. We done come mighty nigh ter de place, an’ ef you wan ter do some ol’ time laughin’, you’ll hatter do des like I tell you; ef you don’t wanter laugh, I’ll des show you de place, an’ we’ll go on back whar we come fum, kaze dis is one er de days dat I ain’t got much time ter was’e laughin’ er cryin’.’ Brer Fox ’low dat he ain’t so mighty greedy ter laugh, an’ wid dat, Brer Rabbit whirl roun’, he did, an’ make out he gwine on back whar he live at. Brer Fox holler at ’im; he say, ‘Come on back, Brer Rabbit; I’m des a-projickin’ wid you.’

“‘Ef you wanter projick, Brer Fox, you’ll hatter go home an’ projick wid dem what wanter be projicked wid. I ain’t here kaze I wanter be here.[69] You ax me fer ter show you my laughin’-place, an’ I ’greed. I speck we better be gwine on back.’ Brer Fox say he come fer ter see Brer Rabbit’s laughin’-place, an’ he ain’t gwineter be satchify twel he see it. Brer Rabbit ’low dat ef dat de case, den he mus’ ac’ de gentermun all de way thoo, an’ quit his behavishness. Brer Fox say he’ll do de best he kin, an’ den Brer Rabbit show ’im a place whar de bamboo briars, an’ de blackberry bushes, an’ de honeysuckles done start ter come in de pine thicket, an’ can’t come no furder. ’Twa’n’t no thick place; ’twuz des whar de swamp at de foot er de hill peter’d out in tryin’ ter come ter dry lan’. De bushes an’ vines wuz thin an’ scanty, an’ ef dey could ’a’ talked dey’d ’a’ hollered loud fer water.

“Brer Rabbit show Brer Fox de place, an’ den tell ’im dat de game is fer ter run full tilt thoo de vines an’ bushes, an’ den run back, an’ thoo um ag’in an’ back, an’ he say he’d bet a plug er terbacker ’g’in a ginger cake dat by de time Brer Fox done dis he’d be dat tickled dat he can’t stan’ up fer laughin’. Brer Fox shuck his head; he[70] ain’t nigh b’lieve it, but fer all dat, he make up his min’ fer ter do what Brer Rabbit say, spite er de fack dat his ol’ ’oman done tell im ’fo’ he lef’ home dat he better keep his eye open, kaze Brer Rabbit gwineter run a rig on ’im.

“His ol’ ’oman done tell him dat he better keep his eye open”

“He tuck a runnin’ start, he did, an’ he went thoo de bushes an’ de vines like he wuz runnin’ a race. He run an’ he come back a-runnin’, an’ he run back, an’ dat time he struck sump’n wid his[71] head. He try ter dodge it, but he seed it too late, an’ he wuz gwine too fas’. He struck it, he did, an’ time he do dat, he fetched a howl dat you might ’a’ hearn a mile, an’ atter dat, he holler’d yap, yap, yap, an’ ouch, ouch, ouch, an’ yow, yow, yow, an’ whiles dis wuz gwine on Brer Rabbit wuz thumpin’ de ground wid his behime foot, an’ laughin’ fit ter kill. Brer Fox run roun’ an’ roun’, an’ kep’ on snappin’ at hisse’f an’ doin’ like he wuz tryin’ fer ter t’ar his hide off. He run, an’ he roll, an’ wallow, an’ holler, an’ fall, an’ squall twell it look like he wuz havin’ forty-lev’m duck fits.

“An’ dat time he struck sump’n wid his head”

“He got still atter while, but de mo’ stiller he got, de wuss he looked. His head wuz all swell up, an’ he look like he been run over in de road by a fo’-mule waggin. Brer Rabbit ’low, ‘I’m glad you had sech a good time, Brer Fox; I’ll hatter fetch you out ag’in. You sho’ done like you wuz havin’ fun.’ Brer Fox ain’t say a word; he wuz too mad fer ter talk. He des sot aroun’ an’ lick hisse’f an’ try ter git his ha’r straight. Brer Rabbit ’low, ‘You ripped aroun’ in dar twel I wuz skeer’d you wuz gwine ter hurt yo’se’f, an’ I b’lieve in my soul you done gone an’ bump yo’ head ag’in a tree, kaze it’s all swell up. You better go home, Brer Fox, an’ let yo’ ol’ ’oman poultice you up.’

“Brer Fox show his tushes, an’ say, ‘You said dis wuz a laughin’-place.’ Brer Rabbit ’low, ‘I said ’twuz my laughin’-place, an’ I’ll say it ag’in. What you reckon I been doin’ all dis time? Ain’t you hear me laughin’? An’ what you been doin’? I hear you makin’ a mighty fuss in dar, an’ I say ter myse’f dat Brer Fox is havin’ a mighty big time.’

“‘I let you know dat I ain’t been laughin’,’ sez Brer Fox, sezee.”

Uncle Remus paused, and waited to be questioned. “What was the matter with the Fox, if he wasn’t laughing?” the child asked after a thoughtful moment.

Uncle Remus flung his head back, and cried out in a sing-song tone,

VI

WHEN BROTHER RABBIT WAS KING

One afternoon, while Uncle Remus was sitting in the sun, he felt so comfortable and thankful for all the blessings that he enjoyed, and for those that he had seen others enjoy, that he suddenly closed his eyes; and he had no sooner done so than he drifted across the dim and pleasant borderland that lies somewhere between sleeping and waking. He must have drifted back again immediately, for it seemed that he was not so fast asleep that he was unable to hear the sound of stealthy footsteps somewhere near him. Instantly he was on the alert, but still kept his eyes closed. He knew at once that the little boy was trying to surprise him. The lad had improved much in health since coming to the plantation, and with the growth of his strength had come a certain degree of boisterousness that his[102] mother thought was somewhat unusual, but which his grandmother and Uncle Remus knew was the natural result of good health.

By opening one eye a trifle, Uncle Remus could watch the youngster, who was creeping, Indian-like, upon him, and this gave the old negro an immense advantage, for just as the little boy was about to jump at him, Uncle Remus straightened himself in his chair and uttered a blood-curdling yell that would have alarmed a much larger and older person than the lad. As a matter of fact, the little fellow was almost paralyzed with fright, and for a moment or two could hardly get his breath.

“Why, what in the world is the matter with you, Uncle Remus?” he asked as soon as he could speak.

“Wuz dat you comin’ ’long dar, honey?” said Uncle Remus, by way of response. “Well, ef ’twuz, you kin des go up dar ter de big house an’ tell um all dat you saved my life, kaze dat what you done. Dey ain’t no tellin’ what would ’a’ happen ef you hadn’t ’a’ come creepin’ ’long an’[103] woke me up, kaze whiles I wuz dozin’ dar I wuz on a train, an’ de bullgine look like it wuz runnin’ away. ’Twant one er deze yer ’commydatin’ trains, kaze de man what tuck up de tickets say he wa’n’t in no hurry fer ter see how fur anybody gwine; dey wuz all boun’ fer de same place, an’ when dey got dar dey’d know it. De kyars wuz lined wid caliker, an’ de brakeman wuz made out’n straw. It went on, it did, an’ de bullgine run faster an’ faster twel it run so fast you couldn’t hear it toot fer brakes, an’ des ’bout de time dat eve’ything wuz a gittin’ smashed up, here you come an’ wokened me—an’ a mighty good thing, kaze ef I’d ’a’ stayed on dat train dey wouldn’t ’a’ been ’nough er me left fer de congergation ter sing a song over. I’m mighty thankful dat dey’s somebody got sense ’nough fer ter come ’long an’ skeer me out er my troubles.”

This statement was intended to change the course of the little boy’s thoughts—to cause him to forget that he had been frightened—and it was quite successful, for he began to talk about[104] dreams in general, telling some peculiar ones of his own, such as children have.

“Talkin’ ’bout dreams,” remarked Uncle Remus, “it put me in min’ er de man what been sick off an’ on, an’ he hatter be mighty keerful er his eatin’. One night he had a dream. It seemed like dat somebody come ’long an’ gi’ him a great big hunk er ol’ time ginger-cake, an’ it smell so sweet an’ taste so good dat he e’t ’bout a poun’. He wuz eatin’ it in his sleep, but de dream wuz so natchal dat de nex’ mornin’ dey hatter sen’ fer de doctor, an’ ’twuz e’en ’bout all dey could do fer ter pull ’im thoo. De doctor gun ’im all de truck what he had in his saddle-bags, an’ ’low dat he b’lieve in his soul he’d hatter sen’ fer mo’, an’ den atter dat he tuck an’ lay down de law ter de man. He say dat whatsomever else he mought do, he better not eat no ginger-cakes in his dreams, kaze de next un ’ud be sho’ fer ter take ’im off spite er all de doctor truck in de roun’ worl’.”

Then the little boy told of a dream he had had. It seems that he had slipped into the pantry,[105] when no one was looking, and had taken a piece of apple-pie. It wasn’t stealing, he said, for he knew that if he asked his grandmother for a piece she would have given it to him; but he didn’t want to bother her while she was talking to the sewing-woman, and so he just went in the pantry and got it for himself. Perhaps he took a larger piece than his grandmother would have given him, but he had nothing to measure it by, and so he was compelled to guess how much she would have given him.

“I boun’ you stretched yo’ guesser, honey,” said Uncle Remus dryly.

The child admitted with a laugh that perhaps he had, and he was very sorry of it afterwards, for when he went to bed he dreamed that something scratched at his door and made such a fuss that he was obliged to get up and let it in. He didn’t wait to see what it was, but just flung the door open, and ran and jumped back in bed, pulling the cover over his head. In the dream he lay right still and listened. Everything was so quiet that he became curious, and finally ventured to look out[106] from under the cover. Well, sir, the sight that he saw was enough, for between the door and the bed a big black dog was lying. He seemed to be very tired, for his tongue hung out long and red, and he was panting as though he had come a long way in a very short time.

Uncle Remus groaned in sympathy. The black dog that gallops through a dream with his tongue hanging out was one of his familiars. “I know dat dog,” he said. “He got a bunch er white on de een’ er his tail, an’ his eyeballs look like dey green in de dark. You call him an’ he’ll growl, call him ag’in, an’ he’ll howl. I’d know dat dog ef I wuz ter see him in de daytime—I’d know him so well dat I’d run an’ ax somebody fer ter please, suh, wake me up, an’ do it mighty quick.”

The little boy didn’t know anything about that; what he did know was that the dog in his dream, when he had rested himself, jumped up on the bed, and began to nose at the cover, and he seemed to get mad when he failed to pull it off the little boy. He tried and tried, and then he[107] seized a corner of the counterpane, or the spread, or whatever you call it, and shook it with his teeth. When he grew tired of this, the little boy could hear him smelling all about over the bed, and then he knew the creature was hunting for the piece of apple-pie.

Uncle Remus agreed with the child about this. “’Cordin’ ter my notion,” he said, “when folks slip ’roun’ an’ take dat what don’t b’long ter um er dat what dey oughtn’t ter have by good rights, de big black dog is sho’ ter come ’roun’ growlin’ an’ smellin’ atter dey goes ter bed. Dey ain’t no two ways ’bout dat. Dey may not know it, dey may be too sleepy fer ter see ’im in der dreams, but de dog’s dar. Mo’ dan dat, dogs will growl an’ smell ’roun’ ef deyer in dreams er outer dreams. Dey got in de habits er smellin’ ’way back yander in de days when ol’ Brer Rabbit had tooken de place er de King one time when de King wanter go off down de country fishin’.”

The little boy seemed to be very much interested in this information, but while they were speaking of this curious habit that is common to dogs,[108] a hound that had been raised on the place came into view. He was going at a gallop, as if he had important business to attend to, but when he had galloped past a large tree, he paused suddenly, and turned back to investigate it with his nose; and though he was entirely familiar with the tree, it seemed to be new to him now, for he smelled all around the trunk of it and was apparently much perplexed. Whatever information he received was sufficient to cause him to forget all about the business that had caused him to come galloping past the tree, for when his investigation had ended, he turned about and went back the way he had come.

“Now, you see dat, don’t you?” exclaimed Uncle Remus, with some show of indignation. “Ain’t it des a little mo’ dan you wanter stan’? Here he come, gwine, I dunner whar, des a-gallin’-up like he done been sent fer. He come ter dat ar tree, he did, an’ went on by—spang by!—an’ den ’fo’ you kin bat yo’ eyeball, whiff, he turn roun’ an’ go ter smellin’ at de tree, des like he ain’t never seed it befo’; an’ he must ’a’ got[109] some kind er news whar he smellin’ at, kaze atter he smell twel it look like he gwineter smell de bark clean off, he fergit all ’bout whar he gwine, an’ tuck his tail an’ go on back whar he come fum. Maybe you know sump’n ’bout it, honey—you an’ de balance er de white folks, but me—I’m bofe blin’ an’ deff when it come ter tellin’ you what de dog foun’ out. I may know what make ’im smell at de tree, but what news he got I never is ter tell you.”

“Well, you know you said that dogs got in the habit of smelling away back yonder when old Brother Rabbit took the place of the King, who had gone fishing. I was wondering if that was a story.”

“Wuz you, honey?” Uncle Remus asked with a pleased smile. “Well, you sho’ is got a dumplin’ eye fer de kinder tales what I tells. I b’lieve ef I wuz ter take one er dem ol’-time tales an’ skin it an’ drag de hide thoo de house an’ roun’ de lot—ef I wuz ter do dat, I b’lieve you’d open up on de trail same ez ol’ Louder follerin’ on atter Brer Possum; I sho’ does!”

“Some run fer ter dig bait”

The child seemed to appreciate the compliment, and he laughed in a way that did the old negro a world of good. “I have found out one thing,” said the little boy with emphasis. “Whenever you are hinting at a story, you always look at me out of the corner of your eye, and there’s always a funny little wrinkle at the corner of your mouth.”

“Well, suh!” exclaimed Uncle Remus, gleefully; “well, suh! an’ me a-settin’ right here an’ doin’ dat a-way ’fo’ yo’ face an’ eyes! I never would ’a’ ’speckted it. Peepin’ out de cornder er my eyeball, an’ a-wrinklin’ at de mouf! It look like I mus’ be gettin’ ol’ an’ fibble in de min’.” He chuckled as proudly as if some one had given him a piece of pound-cake of which he was very fond. But presently his chuckling ceased, and he leaned back in his chair with a serious air.

“I dunno so mighty well ’bout all de yuther times you talkin’ ’bout, honey, but when I say what I did ’bout ol’ Brer Rabbit takin’ de place er der King, I sho’ had a tale in my min’. I say tale, but I dunner what you’ll say ’bout it; you[111] kin name it atter you git it. Well, way back yander, mos’ ’fo’ de time when folks got in de habits er dreamin’ dreams, dey wuz a King an’ dish yer King king’d it over all un um what wuz dar, mo’ speshually de creeturs, kaze what folks dey wuz ain’t know nothin’ ’tall ’bout whedder dey need any kingin’ er not; look like dey didn’t count.

“Well, dish yer King what I’m a-tellin’ you ’bout had purty well grow’d up at de business, and de time come when he got mighty tired er settin’ in one place an’ hol’in’ a crown on his head fer ter keep it fum fallin’ on de flo’. He say ter hisse’f dat he wanter git out an’ git de fresh a’r, an’ have some fun ’long wid dem what he been kingin’ over. He ’low dat he wanter fix it so dat he ain’t a-keerin’ whedder school keep er no, an’ he ax um all what de best thing he kin do. Well, one say one thing an’ de yuther say t’other, but bimeby some un um chipped in an’ say dat de best way ter have fun is ter go fishin’, an’ dis kinder hit de King right in de middle er his notions.

“He jump up an’ crack his heels tergedder, he[112] did, an’ he say dat dat’s what he been thinkin’ ’bout all de time. A-fishin’ it wuz an’ a-fishin’ he’d go, ef his life wuz spar’d twel he kin git ter de creek. An’, wid dat, dey wuz a mighty stirrin’ roun’ ’mongs’ dem what he wuz a-kingin’ over; some un um run off ter git fishin’-poles, an’ some run fer ter dig bait, an’ some run fer ter git de bottle, an’ dar dey had it—you’d ’a’ thunk dat all creation wuz gwine fishin’.”

“Uncle Remus,” said the little boy, interrupting[113] the old man, “what did they want with a bottle?”

The old man looked at the child with a puzzled expression on his face. “De bottle?” he asked with a sigh. “I b’lieve I did say sump’n ’bout de bottle. I dunner whedder it ’uz a long white bottle er a chunky black un. Dem what handed de tale down ter me ain’t say what kinder one it wuz, an’ I’m fear’d ter say right short off dat it ’uz one er de yuther. We’ll des call it a plain, eve’yday bottle an’ let it go at dat.”

“But what did they want with a bottle, Uncle Remus?” persisted the little boy.

“You ain’t never been fishin’, is you honey? An’ you ain’t never see yo’ daddy go fishin’. All I know is dat whar dey’s any fishin’ gwine on, you’ll fin’ a bottle some’rs in de neighborhoods ef you’ll scratch about in de bushes. Well, de creeturs done like folks long ’fo’ folks got ter doin’ dat a-way, an’ when dish yer King went a-fishin’, he had ter have a bottle fer ter put de bait in.

“When eve’ything got good an’ ready, an’ de King wuz ’bout ter start off, ol’ Brer Rabbit kinder hung his head on one side an’ set up a snigger. De King, he look ’stonish an’ den he ’low, ‘What’s de joke, ol’ frien’?’ ‘Well,’ sez ol’ Brer Rabbit, sezee, ‘it look like ter me dat you ’bout ter go off an’ fergit sump’n. ’Tain’t none er my business, but I couldn’t he’p fum gigglin’.’ De King, he say, ‘Up an’ out wid it, ol’ frien’; le’s hear de wust dey is ter hear.’ Ol’ Brer Rabbit, he say, sezee, ‘I dunner ef it makes any diffunce, but who gwine ter do de kingin’ whiles you gone a-fishin’?’

“De King … sot right flat in a cheer”

“Well, de King look like he wuz might’ly tuck back; he flung up bofe han’s an’ sot right flat in a cheer, an’ den he ’low, ‘I done got so dat I’m de fergittines’ creetur what live on top er de groun’; you may hunt high an’ low an’ you won’t never fin’ dem what kin beat me a-fergittin’. Here I wuz ’bout fer ter go off an’ leave de whole business at sixes an’ sev’ms.’ Ol’ Brer Rabbit, he say, sezee, ‘Oh, I speck dat would ’a’ been all right; dey ain’t likely ter be no harrycane, ner no fresh’ whiles you gone.’ De King, he ’low, ‘Dat ain’t de thing; here I wuz ’bout ter go off on a frolic an’ leave eve’ything fer ter look atter itse’f. What yo’ reckon folks would ’a’ said? I tell you now, dey ain’t no fun in bein’ a King, kaze yo’ time ain’t yo’ own, an’ you can’t turn roun’ widout skinnin’ yo’ shins on some by-law er ’nother. ’Fo’ I go, ef go I does, I got ter ’p’int somebody fer ter take my place an’ be King whiles I’m gone; an’ ef ’twant dat, it’d be sump’n’ else, an’ so dar you go year in an’ year out.’

“Dey ain’t no fun in bein’ a King”

“He sot dar, he did, an’ study an’ study, an’ bimeby he say, sezee, ‘Brer Rabbit,[117] s’posin’ you take my place whiles I’m gone? I’ll pay you well; all you got to do is ter set right flat in a cheer an’ make a dollar a day.’ Ol’ Brer Rabbit say dat would suit him mighty well, kaze he bleeze fer ter have some money so he kin buy his ol’ ’oman a caliker dress. Well, it ain’t take um long fer ter fix it all up, an’ so Brer Rabbit, he done de kingin’ whiles de King gone a-fishin’. He made de job a mighty easy one, kaze stidder settin’ up an’ hol’in’ de crown on his head, he tied some strings on it an’ fix it so it’d stay on his head widout hol’in’.

“When de King went a-fishin’, he went de back way”

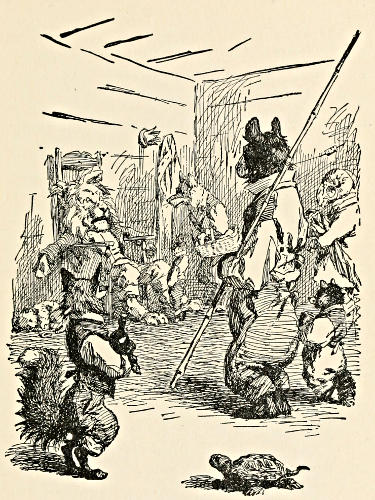

“Well, when de King went a-fishin’, he went[118] de back way, an’ he ain’t mo’ dan got out de gate twel ol’ Brer Rabbit hear a big rumpus in de front yard. He hear sump’n’ growlin’ an’ howlin’ an’ whinin’, an’ he ax what it wuz. Some er dem what wait on de King shuck der heads an’ say dat ef de King wuz dar he wouldn’t pay no ’tention ter de racket fer der longest; dey say dat de biggest kind er fuss ain’t ’sturb de King, kaze he’d des set right flat an’ wait fer some un ter come tell somebody what de rumpus is ’bout, an’ den dat yuther somebody would tell some un else, an’ maybe ’bout dinner-time de King would fin’ out what gwine on, when all he hatter do wuz ter look out de winder an’ see fer hisse’f.

“Some er dem what wait on de King shuck der heads”

“He lay back … wid dat ar crown on top er his head, an’ make out he takin’ a nap”

“When ol’ Brer Rabbit hear dat, he lay back ez well ez he kin wid dat ar crown on top er his head, an’ make out he takin’ a nap. Atter so long a time, word come dat Mr. Dog wuz[119] out dar in de entry whar dey all hatter wait at, an’ he sont word dat he bleeze ter see de King. Ol’ Brer Rabbit, he sot dar, he did, an’ do like he studyin’, an’ atter so long a time, he tell um fer ter fetch Mr. Dog in an’ let him say what he got ter say. Well, Mr. Dog come creepin’ in, he did, an’ he look mighty ’umble-come-tumble. He wuz so po’ dat it look like you can see eve’y bone in his body an’ he wuz mangy lookin’. His head hung down, an’ he wuz kinder shiverin’ like he wuz col’. Brer Rabbit make out he tryin’ fer ter fix de crown on his head so it’ll set up straight, but all de time he[120] wuz lookin’ at Mr. Dog fer ter see ef he know’d ’im—an’ sho’ ’nough, he did, kaze it uz de same Mr. Dog what done give him many a long chase.

“Well Mr. Dog come creepin’ in”

“Well, Mr. Dog, he stood dar wid his head hangin’ down an’ his tail ’tween his legs. Eve’ything wuz so still an’ sollum dat he ’gun ter git oneasy, an’ he look roun’ fer ter see ef dey’s any[121] way fer ter git out widout runnin’ over somebody. Dey ain’t no way, an’ so Mr. Dog sorter wiggle de een’ er his tail fer ter show dat he ain’t mad, an’ he stood dar ’specktin’ dat eve’y minnit would be de nex’.

“Bimeby, somebody say, ‘Who dat wanter see de King an’ what business is he got wid ’im?’ When Mr. Dog hear dat, de howl dat he sot up mought ’a’ been heern a mile er mo’. He up an’ ’low, he did, dat him an’ all his tribe, an’ mo’ speshually his kinnery, is been havin’ de wuss times dat anybody ever is hear tell un. He say dat whar dey use ter git meat, dey now gits bones, an’ mighty few er dem, an’ whar dey use ter be fat, dey now has ter lean up ag’in de fence, an’ lean mighty hard, ef dey wanter make a shadder. Mr. Dog had lots mo’ ter say, but de long an’ de short un it wuz dat him an’ his kinnery wa’n’t treated right.

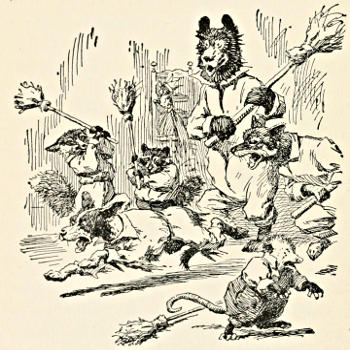

“Ol’ Brer Rabbit, which he playin’ King fer de day, he kinder study, an’ den he cle’r up his th’oat an’ look sollum. He ax ef dey’s any turkentime out dar in de back yard er in de cellar[122] whar dey keep de harness grease, an’ when dey say dey speck dey’s a drap er two lef’, ol’ Brer Rabbit tell um fer ter fetch it in, an’ den he tell um ter git a poun’ er red pepper an’ mix it wid de turkentime. So said, so done. Dey grab Mr. Dog, an’ rub de turkentime an’ red pepper frum head ter heel, an’ when[123] he holler dey run ’im out’n de place whar de kingin’ wuz done at.

“Dey run im out’n de place whar de kingin’ wuz done at”

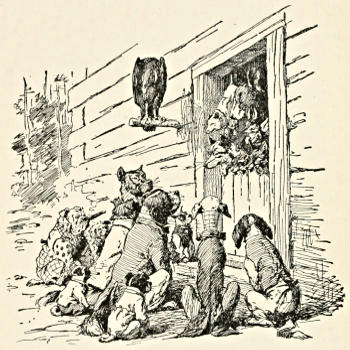

“Well, time went on, an’ one day follered an’er des like dey does now, an’ Mr. Dog ain’t never gone back home, whar his tribe an’ his kinnery wuz waitin’ fer ’im. Dey wait, an’ dey wait, an’ bimeby dey ’gun ter git oneasy. Den dey wait some mo’ but it git so dey can’t stan’ it no longer, an’ den a whole passel un um went ter de house whar dey do de kingin’ at, an’ make some inquirements ’bout Mr. Dog. Dem dat live at de King’s house up an’ tell um dat Mr. Dog done come an’ gone. Dey say he got what he come atter, an’ ef he ain’t gone back home dey dunner whar he is. Dey tol’ ’bout de po’ mouf he put up, an’ dey say dat dey gun ’im purty well all dat a gen’termun dog could ax fer.

“De yuther dogs say dat Mr. Dog ain’t never come back home, an’ dem what live at de King’s house say dey mighty sorry fer ter hear sech bad news, an’ dey tell de dogs dat dey better hunt ’im up an’ fin’ out what he done wid dat what de king gi’ ’im. De dogs ax how dey gwineter know[124] ’im when dey fin’ him, an’ dem at de King’s house say dey kin tell ’im by de smell, kaze dey put some turkentime an’ red pepper on ’im fer ter kill de fleas an’ kyo de bites. Well, sence dat day de yuther dogs been huntin’ fer de dog what went ter de King’s house; an’ how does dey hunt? ’Tain’t no needs fer ter tell you, honey, kaze you know[125] pine-blank ez good ez I kin tell you. Sence dat day an’ hour dey been smellin’ fer ’im. Dey smells on de groun’ fer ter see ef he been ’long dar; dey smells de trees, de stumps, an’ de bushes, an’ when dey comes up wid an’er dog dat dey ain’t never seed befo’, dey smells him good fer ter see ef he got any red pepper an’ turkentime on ’im; an’ ef you’ll take notice dey sometimes smells at a bush er a stump, an’ der bristles will rise, an’ dey’ll paw de groun’ wid der fo’ feet, an’ likewise wid der behime feet, an’ growl like deyer mad. When dey do dat, dey er tellin’ you what dey gwineter do when dey git holt er dat dog what went to de King’s house an’ ain’t never come back. I may be wrong, but I’ll bet you a white ally ag’in’ a big long piece er mince-pie dat dey’ll be gwine on dat a-way when you git ter be ol’ ez I is.”

“A whole passel un um went ter de house whur dey do the kingin’”

.

.

.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.