THE NEW FOREST:

ITS

History and its Scenery.

BY John R Wise

Illustrated by Walter Crane

.

. .

.  .

. .

.  .

.  .

. .

.  .

.  .

.  .

. .

.  .

.

.

. .

.

.

.  .

. .

. .

.

CHAPTER XVI.

THE FOLK-LORE AND PROVINCIALISMS.

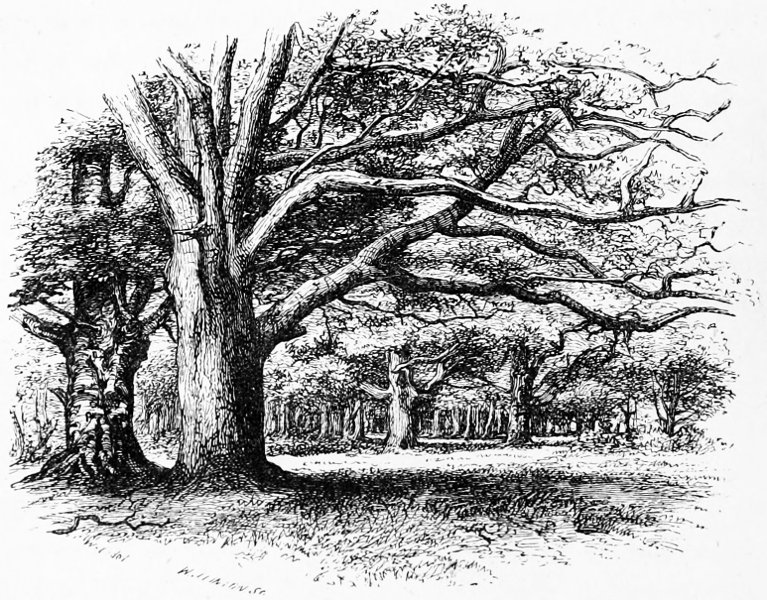

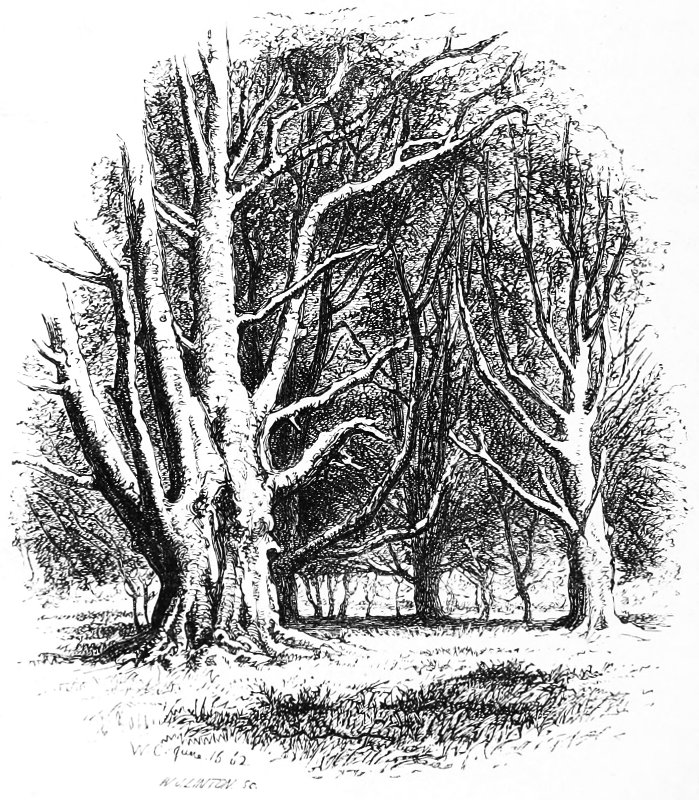

Anderwood Corner.

Intimately bound up with the race are of course the folk-lore of a district, and what we are now pleased to call provincialisms, but which are more properly nationalisms, showing us the real texture of our language; and in every way preferable to the 173Latin and Greek hybridisms, which are daily coined to suit the exigencies of commerce or science.

Provincialisms are, in fact, when properly looked at, not so much portions of the original foundations of a language, as the very quarry out of which it is hewn. And as if to compensate for much of the harm she has done, America has wrought one great good in preserving many a pregnant Old-English word, which we have been foolish enough to disown.[212] Provincialisms should be far more studied than they are; for they will help us to settle many a difficult point,—where was the boundary of the Anglian and the Frisian? how far on the national character was the influence of the Dane felt? how much, and in what way, did the Norman affect the daily business of life?

Still more important is a country’s folk-lore, as showing the higher mental faculties of the race, in those legends and snatches of song, and fragments of popular poetry, which speak the popular feeling, and which not only contain its past history, but foreshadow the future literature of a country; in those proverbs, too, which tell the life and employment of a nation; and those superstitions which give us such an insight into its moral state.

Throughout the West of England still linger some few 174stray waifs and legends of the past. In the New Forest Sir Bevis of Southampton is no mythical personage, and the peasant will tell how the Knight used to take his afternoon’s walk, across the Solent, from Leap to the Island.

Here in the Forest still dwell fairies. The mischievous sprite, Laurence, still holds men by his spell and makes them idle. If a peasant is lazy, it is proverbially said, “Laurence has got upon him,” or, “He has got a touch of Laurence.” He is still regarded with awe, and barrows are called after him. Here, too, in the Forest still lives Shakspeare’s Puck, a veritable being, who causes the Forest colts to stray, carrying out word for word Shakspeare’s description,—

“I am that merry wanderer of the night,

When I a fat and bean-fed horse beguile

Neighing in likeness of a filly foal.”

(Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act ii., Sc. 1.)

This tricksy fairy, so the Forest peasant to this hour firmly believes, inhabits the bogs, and draws people into them, making merry, and laughing at their misfortunes, fulfilling his own roundelay—

“Up and down, up and down,

I will lead them up and down;

I am feared in field and town,

Goblin, lead them up and down.”

(Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act iv., Sc. 2.)

Only those who are eldest born are exempt from his spell. The proverb of “as ragged as a colt Pixey” is everywhere to be heard, and at which Drayton seems to hint in his Court of Faerie:—

“This Puck seems but a dreaming dolt,

Still walking like a ragged colt.”

He does not, however, in the Forest, so much skim the milk, or 175play pranks with the chairs, but, as might be expected from the nature of the country, misleads people on the moors, turning himself into all sorts of shapes, as Shakspeare, Spenser, and Jonson, have sung. There is scarcely a village or hamlet in the Forest district which has not its “Pixey Field,” and “Pixey Mead,” or its “Picksmoor,” and “Cold Pixey,” and “Puck Piece.” At Prior’s Acre we find Puck’s Hill, and not far from it lies the great wood of Puckpits; whilst a large barrow on Beaulieu Common is known as the Pixey’s Cave.[213]

Then, too, on the south-west borders of the Forest remains the legend, its inner meaning now perhaps forgotten, that the Priory Church of Christchurch was originally to have been built on the lonely St. Catherine’s Hill, instead of in the valley where the people lived and needed religion. The stones, however, which were taken up the hill in the day were brought down in the night by unseen hands. The beams, too, which were found too short on the heights, were more than long enough in the town. The legend further runs, beautiful in its right interpretation, that when the building was going on, there was always one more workman—namely, Christ—than came on the pay-night.

So, too, the poetry of the district has its own characteristics, which it shares with that of the neighbouring western counties. The homeliness of the songs in the West of England strangely 176contrasts with the wild spirit of those of the North, founded as the latter so often are on the border forays and raids of former times. None which I have collected are direct enough in their bearing on the New Forest to warrant quotation, and I must content myself with this general expression.[214]

To pass on to other matters, let us notice some of the superstitions of the New Forest. No one is now so superstitious, because no one is so ignorant as the West-Saxon. One of the commonest remedies for consumption in the Forest is the “lungs of oak,” a lichen (Sticta pulmonaria) which grows rather plentifully on the oak trees; and it is no unfrequent occurrence for a poor person to ask at a chemist’s shop for a “pennyworth of lungs of oak.” So, too, for weak eyes, “brighten,” another lichen, is recommended. I do not know, however, that we must find so much fault in this matter, as the lichens were not very long ago favourite prescriptions with even medical men.

Again, another remedy for various diseases used to be the scrapings from Sir John Chydioke’s alabaster figure, in the Priory Church of Christchurch, which has, in consequence, been sadly injured. A specific, however, for consumption is still to kill a jay and place it in the embers till calcined, when it is 177then drunk at stated times in water. Hares’ brains are recommended for infants prematurely born. Children suffering from fits are, or rather were, passed through cloven ash-trees. Bread baked on Good Friday will not only keep seven years, but is a remedy for certain complaints. The seventh son of a seventh son can perform cures. In fact, a pharmacopœia of such superstitions might be compiled.

The New Forest peasant puts absolute faith in all traditions, believing as firmly in St. Swithin as his forefathers did when the saint was Bishop of Winchester; turns his money, if he has any, when he sees the new moon; fancies that a burn is a charm against leaving the house; that witches cannot cross over a brook; that the death’s-head moth was only first seen after the execution of Charles I.; that the man in the moon was sent there for stealing wood from the Forest—a superstition, by the way, mentioned in a slightly different form by Reginald Pecock, Bishop of Chichester, in the fifteenth century.[215] And the “stolen bush,” referred to by Caliban in the Tempest (Act ii. sc. 2), and Bottom in the Midsummer Night’s Dream (Act vi. sc. 1), is still here called the “nitch,” or bundle of faggots.[216]

Not only this, but the barrows on the plains are named after the fairies, and the peasant imagines, like the treasure-seekers of the Middle-Ages, that they contain untold wealth, and that the Forest wells are full of gold.[217]

I do not mean, however, to say that these beliefs are openly 178avowed, or will even be acknowledged by the first labourer who may be seen. The English peasant is at all times excessively chary—no one perhaps more so—of expressing his full mind; and a long time is required before a stranger can, if ever, gain his confidence. But I do say that these superstitions are all, with more or less credit, held in different parts of the Forest, although even many who believe them the firmest would shrink, from fear of ridicule, to confess the fact. Education has done something to remove them; but they have too firm a hold to be easily uprooted. They may not be openly expressed, but they are, for all that, to my certain knowledge, still latent.

Old customs and ceremonies still linger. Mummers still perform at Christmas. Old women “go gooding,” as in other parts of England, on St. Thomas’s Day. Boys and girls “go shroving” on Ash Wednesday; that is, begging for meat and drink at the farm-houses, singing this rude snatch:—

“I come a shroving, a shroving,

For a piece of pancake,

For a piece of truffle-cheese[218]

Of your own making.”

When, if nothing is given, they throw stones and shards at the door.[219]

Plenty, too, of old love superstitions remain—about ash boughs with an even number of leaves, and “four-leaved” clover, concerning which runs a Forest rhyme:—

“Even ash and four-leaved clover,

You are sure your love to see

Before the day is over.”

Then, too, we must not forget the Forest proverbs. “Wood Fidley rain,” “Hampshire and Wiltshire moon-rakers,” and “Keystone under the hearth,” have already been noticed. But there are others such as “As yellow as a kite’s claw,” “An iron windfall,” for anything unfairly taken, “All in a copse,” that is, indistinct, “A good bark-year makes a good wheat-year,” and “Like a swarm of bees all in a charm,” explained further on, which show the nature of the country. Again, “A poor dry thing, let it go,” a sort of poacher’s euphemism, like, “The grapes are sour,” is said of the Forest hares when the dogs cannot catch them, and so applied to things which are coveted but out of reach. “As bad as Jeffreys” preserves, as throughout the West of England, the memory of one who, instead of being the judge, should have been the hangman. Again, too, “Eat your own side, speckle-back,” is a common Forest expression, and is used in reference to greedy people. It is said to have taken its origin from a girl who shared her breakfast with a snake, and thus reproved her favourite when he took too much. Again, “To rattle like a boar in a holme bush,” is a thorough proverb of the Forest district, where a “holme” bush means an old holly. Passing, however, from particulars to generals, let me add for the last, “There is but one good mother-in-law, and she is dead.” I have never heard it elsewhere in England, but doubtless it is common enough. It exactly corresponds with the German saying, “There is no good mother-in-law but she that 180wears a green gown,” that is, who lies in the churchyard. The shrewdness and humour of a people are never better seen than in their proverbs.

Further, there are plenty of local sayings, such as “The cuckoo goes to Beaulieu Fair to buy him a greatcoat,” referring to the arrival of the cuckoo about the 15th of April, whilst the day on which the fair is held is known as the “cuckoo day.” A similar proverb is to be found in nearly every county. So, also, the saying with regard to Burley and its crop of mast and acorns may be met in the Midland districts concerning Pershore and its cherries. Like all other parts of England, the Forest is full, too, of those sayings and adages, which are constantly in the mouths of the lower classes, so remarkable for their combination of both terseness and metaphor. To give an instance, “He won’t climb up May Hill,” that is, he will not live through the cold spring. Again, “A dog is made fat in two meals,” is applied to upstart or purse-proud people. But it is dangerous to assign them to any particular district, as by their applicability they have spread far and wide.

One or two historical traditions, too, still linger in the Forest, but their value we have seen with regard to the death of the Red King. Thus, the peasant will tell of the French fleet, which, in June, 1690, lay off the Needles, and of the Battle of Beachy Head—its cannonading heard even in the Forest—but who fought, or why, he is equally ignorant. One tradition, however, ought to be told concerning the terrible winter of 1787, still known in the Forest as “the hard year.” My informant, an old man, derived his knowledge from his father, who lived in the Forest in a small lonely farm-house. The storm began in the night; and when his father rose in the morning he could not, on account of the snow-drift, open the door. Luckily, a back 181room had been converted into a fuel-house, and his wife had laid in a stock of provisions. The storm still increased. The straggling hedges were soon covered; and by-and-by the woods themselves disappeared. After a week’s snow, a heavy frost followed. The snow hardened. People went out shooting, and wherever a breathing-hole in the snow appeared, fired, and nearly always killed a hare.[220] The snow continued on the ground for seven weeks; and when it melted, the stiffened bodies of horses and deer covered the plains.[221]

And now for a few of the Forest words and expressions, many of which are very peculiar. Take, for instance, the term “shade,” which here has nothing in common with the shadows of the woods, but means either a pool or an open piece of ground, generally on a hill top, where the cattle in the warm weather collect, or, as the phrase is, “come to shade,” for the sake of the water in the one and the breeze in the other. Thus “Ober Shade” means nothing more than Ober pond; whilst “Stony Cross Shade” is a mere turfy plot. At times as many as a hundred cows or horses are collected together in one of these places, where the owners, or “Forest marksmen,” always first go to look after a strayed animal. Nearly every “Walk” in the Forest has its own “Shade,” called after its own name, and we find the term used as far back as a perambulation of the Forest in the twenty-second year of Charles II., where is mentioned “the Green Shade of Biericombe or Bircombe.”

It affords a good illustration of how words grow in their 182meaning, and imperceptibly pass from one stage to another. It originally signified nothing but a shadow, and then the place where the shadow rests. In this second meaning it more particularly became associated with the idea of coolness, but gradually, whilst acquiring that idea, quite contrary to Milton’s “unpierced shade” (Paradise Lost, B. iv. 245), lost the notion of that coolness being caused by the interception of light and heat. In this sense it was transferred to any place which was cool, and so at last applied, as in the New Forest, to bare spots without a tree, deriving their coolness either from the breeze or the water.

Another instance of the gradual change in the meaning of words amongst provincialisms may be found in “scale,” or “squoyle.” In the New Forest it properly signifies a short stick loaded at one end with lead, answering to the “libbet” of Sussex, and is distinguished from a “snog,” which is only weighted with wood. With it also is employed the verb “to squoyle,” better known in reference to the old sport of “cock-squoyling.” From throwing at the squirrel the word was used in reference to persons, so that “Don’t squoyle at me” at length meant, “Do not slander me.” Lastly, the phrase, now still common, “Don’t throw squoyles at me,” comes by that forced interpretation of obtaining a sense, which nearly always reverses the original meaning, to signify, “Do not throw glances at me.” And so in the New Forest at this day “squoyles” not unfrequently mean glances.

There is, too, the word “hat,” which in the Forest takes the place of “clump,” and is nearly equivalent to the Sussex expression, “a toll of trees.” I have no doubt whatever that the word had its origin in the high-crowned hats of the Puritans, the “long crown” of the proverb; and in the first place referred 183only to tall isolated clumps of trees. Now, however, it does not merely mean a clump or ring, as the “seven firs” between Burley and Ringwood, and Birchen, and Dark Hats, near Lyndhurst, but any small irregular mass of trees, as the Withy Bed Hat in the valley near Boldrewood.

Then of course, in connection with the Forest trees, many peculiar words occur. The flower of the oak is called “the trail,” and the oak-apple the “sheets axe,”—children carrying it on the twenty-ninth of May, and calling out the word in derision to those who are not so provided. The mast and acorns are collectively known as “the turn out,” or “ovest;”[222] whilst the badly-grown or stunted trees are called “bustle-headed,” equivalent to the “oak-barrens” of America.

Other words there are, too, all proclaiming the woody nature of the country. The tops of the oaks are termed, when lopped, the “flitterings,” corresponding to the “batlins” of Suffolk. The brush-wood is still occasionally Chaucer’s “rise,” or “rice,” connected with the German reis; and the beam tree, on account of its silvery leaves, the “white rice.”[223] Frith, too, still means copse-wood. The stem of the ivy is the “ivy-drum.” Stumps of trees are known as “stools,” and a “stooled stick” is used in opposition to “maiden timber,” which has never been touched with the axe; whilst the roots are called “mocks,” “mootes,” “motes,” and “mores.” But about these last, which are all used with nice shades of difference, we shall have, further on, something to say.

Nor must we forget the bees which are largely kept throughout the Forest, feeding on the heather, leading Fuller to remark that Hampshire produced the best and worst honey in England. The bee-season, as it is called, generally lasts, on account of the heath, a month longer than on the Wiltshire downs. A great quantity of the Old-English mead—medu—is still made, and it is sold at much the same value as with the Old-English, being three or four times the price of common beer, with which it is often drunk. The bees, in fact, still maintain an important place in the popular local bye-laws. Even in Domesday the woods round Eling are mentioned as yearly yielding twelve pounds’ weight of honey. As may therefore be expected, when we remember that the whole of England was once called the Honey Island, here, as elsewhere, plenty of provincialisms occur concerning the bees.[224]

The drones are here named “the big bees,” the former word being in some parts seldom used. The young are never said to swarm, but “to play,” the word taking its origin from their peculiar flight at the time: as Patmore writes,—

“Under the chestnuts new bees are swarming,

Falling and rising like magical smoke.”

The caps of straw which are placed over the “bee-pots,” to protect them from wet, are known as the “bee-hackles,” or “bee-hakes.” This is one of those expressive words which is now only found in this form, and that, in the Midland Counties, of “wheat hackling,” that is, covering the sheaves with others in a peculiar way, to shelter them from the rain. About 185the honeycombs, or, as they are more commonly called, “workings,” the following rhyme exists:—

“Sieve upon herder,[225]

One upon the other;

Holes upon both sides,

Not all the way, though,

What may it be? See if you know.”

The entrance for the bees into the hive is here, as in Cambridgeshire and some other counties, named the “tee-hole,” evidently an onomatopoieia, from the buzzing or “teeing” noise, as it is locally called, which the bees make. The piece of wood placed under the “bee-pots,” to give the bees more room, is known as “the rear,” still also, I believe, in use in America. The old superstition, I may notice, is here more or less believed, that the bees must be told if any death happens in a family, or they will desert their hives. It is held, too, rather, perhaps, as a tradition than a law, that if a swarm of bees flies away the owner cannot claim them, unless, at the time, he has made a noise with a kettle or tongs to give his neighbours notice. It is on such occasions that the phrase “Low brown” may be heard, meaning that the bees, or the “brownies,” as they are called, are to settle low.

So also of the cattle, which are turned out in the Forest, we find some curious expressions. A “shadow cow” is here what would in other places be called “sheeted,” or “saddle-backed,” that is, a cow whose body is a different colour to its hind and fore parts.[226] A “huff” of cattle means a drove or herd, whilst the 186cattle, which are entered in the marksman’s books, are said to be “wood-roughed.” A cow without horns is still called a “not cow” (hnot), exactly corresponding to the American “humble” or “bumble cow,” that is, shorn, illustrating, as Mr. Akerman notices,[227] Chaucer’s line,—

“A not hed had he, with a brown visage.”

In the Forest, too, as in all other districts, a noticeable point is the number of words formed by the process of onomatopoieia. Thus, to take a few examples, we have the expressive verb to “scroop,” meaning to creak, or grate, as a door does on rusty hinges; and again the word “hooi,” applied to the wind whistling round a corner, or through the key-hole, making the sound correspond to the sense. It exactly represents the harsh creaking, as the Latin susurrus and the ψιθύρισμα of Theocritus reflect the whisperings of the wind in the pines and poplars, resembling, as Tennyson says, “a noise of falling showers.” Again, such words as “clocking,” “gloxing,” applied to falling, gurgling water; “grizing,” and “snaggling,” said of a dog snarling; “whittering,” or “whickering”—exactly equivalent to the German wiehern—of a young colt’s neighing; “belloking,” of a cow’s lowing—are all here commonly used, and are similarly formed. Names of animals take their origin in the same way. The wry-neck, called the “barley-bird” in Wiltshire, and the “cuckoo’s mate” and “messenger” elsewhere, is in the Forest known as the “weet-bird,” from its peculiar cry of “weet;” which it will repeat at short intervals for an hour together. So, too, the 187common green woodpecker is here, as is in some other parts of England, called, from its loud shrill laugh, the “yaffingale.” The goat-sucker, too, is the “jar-bird,” so known from its jarring noise, which has made the Welsh peasant name it the “wheel-bird” (aderyn y droell), and the Warwickshire the “spinning-jenny.” In fact, a large number of birds in every language are thus called, and to this day in the cry of the peacock we may plainly hear its Greek name, ταῶς.

Of course, we must be on our guard against adopting the onomatopoëtic theory as altogether explaining the origin of language. Within, however, certain limits, especially with a peculiar class of provincialisms, it gives us, as here, true aid.[228]

Again, as an example of phrases used by our Elizabethan poets, preserved only by our peasantry, though in good use in America, take the word “bottom,” so common throughout the Forest, meaning a valley, glen, or glade. Beaumont and Fletcher and Shakspeare frequently employ it. Even Milton, in Paradise Regained, says—

“But cottage, herd, or sheepcote, none he saw,

Only in a bottom saw a pleasant grove.”

(Book ii. 289.)

In his Comus, too, we find him using the compound “bottom-glade,” just as the Americans speak to this day of the “bottom-lands” of the Ohio, and our own peasants of Slufter Bottom, and Longslade Bottom, in the New Forest.

“Heft,” too, is another similar instance of an Old-English word in good use in America and to be found in the best American authors, but here in England only employed by our 188rustics. To “heft” (from hebban, with the inflexions, hefest, “hefð,” still used), signifies to lift, with the implied meaning of weighing. So, “to heft the bee-pots,” is to lift them in order to feel how much honey they contain. The substantive “heft” is used for weight, as, “the heft of the branches.”

Again, also, the good Old-English word “loute” (lutan), to bend, bow, and so to touch the hat, to be heard every day in the Forest, though nearly forgotten elsewhere in England, may be found in Longfellow’s Children of the Lord’s Supper:—

“as oft as they named the Redeemer,

Lowly louted the boys, and lowly the maidens all courtesied.”

In fact, one-half of the words which are considered Americanisms are good Old-English words, which we have been foolish enough to discard.

Let us now take another class of words, which will help to explain difficult or corrupt passages in our poets. There is, for instance, the word “bugle” (buculus), meaning an ox (used, as Mr. Wedgwood[229] notices, in Deut. xiv. in the Bible, 1551), which is forgotten even by the peasantry, and only to be seen, as at Lymington and elsewhere, on a few inn-signs, with a picture sometimes of a cow, by way of explanation. I have more than once thought, that when Rosalind, in As You Like It (Act iii., sc. 5), speaks of Phœbe’s “bugle eyeballs,” she means not merely her sparkling eyes, as the notes say, but rather her large, expressive eyes, in the sense in which Homer calls Herê βοῶπις.

To give another illustration of the value of provincialisms 189in such cases, let us take the word “bumble,” which not only in the New Forest means, in its onomatopoëtic sense, to buzz, hum, or boom, as in the common proverb, “to bumble like a bee in a tar-tub,” and as Chaucer says, in The Wife of Bath’s Tale—

“A bytoure bumbleth in the myre,”

but is also used of people stumbling or halting. Probably, in The Merry Wives of Windsor (Act iii., sc. 3), in the passage which has been of such difficulty to the commentators, where Mrs. Ford says to the servants, who are carrying Falstaffe in the buck-basket—“Look, how you drumble,” which has no meaning at all, we should, instead, read this word. It, at all events, not only conveys good sense, but is the exact kind of word which the passage seems to expect.

Again, the compound “thiller-horse,” from the Old-English “þill,” a beam or shaft, and so, literally, the shaft-horse, which we find in Shakspeare under the form of “thill-horse” (Merchant of Venice, Act ii., sc. 2), is here commonly used.

Then there are other forms among provincialisms which give such an insight into the formation of language, and show the common mind of the human race. Thus, take the word “three-cunning,”[230] to be heard every day in the Forest, where three has the signification of intensity, just as the Greek τρίς in composition in the compounds τρίσμακαρ, τρισάθλιος, and other forms. So, too, the missel-thrush is called the “bull-thrush,” with the meaning of size attached to the word, as it is more commonly to our own “horse,” and the Greek ἵππος, and the Old-English hrefen, raven, in composition.

As might be expected, from what we have seen of the population of the Forest, the Romance element in its provincialisms is very small. Some few words, such as “merry,” for a cherry; “fogey,” for passionate; “futy,” for foolish; “rue,” for a hedge; “glutch,” to stifle a sob—have crept in, besides such Forest terms as verderer, regarder, agister, agistment, &c., but the majority are Teutonic. Old-English inflexions, too, still remain. Such plurals as placen, housen, peasen, gripen, fuzzen, ashen, and hosen, as we find in Daniel, ch. iii. v. 21; such perfects as crope, from creep; lod, from lead; fotch, from fetch; and such phrases as “thissum” (“þissum”), and “thic” for that, are daily to be heard.

Let us, for instance, take the adjective vinney, evidently from the Old-English finie, signifying, in the first place, mouldy; and, since mould is generally blue or purplish, having gradually attached to it the signification of colour. Thus we find the mouldy cheese not only named “vinney,” but a roan heifer called a “vinney heifer.” The most singular part, however, as exemplifying the changes of words, remains to be told. Since cheese, from its colour, was called “vinney,” the word was applied to some particular cheese, which was mouldier and bluer than others, and the adjective was thus changed into a substantive. And we now have “vinney,” and the tautology, “blue vinney,” as the names of a particular kind of cheese as distinguished from the other local cheeses, known as “ommary” and “rammel.”[231]

So also with the word “charm,” or rather “churm,” signifying, in the first place, noise or disturbance, from the Old-English cyrm. We meet it every day in the common Forest 191proverb, “Like a swarm of bees all in a churm,” whilst the fowlers on the coast talk also of the wild ducks “being in a churm,” when they are in confusion, flapping their wings before they settle or rise. We find it, too, in the old Wiltshire song of the “Owl’s Mishap,” to be sometimes heard on the northern borders of the Forest:—

“At last a hunted zo ver away,

That the zun kum peping auver the hills,

And the burds wakin up they did un espy,

And wur arl in a churm az un whetted their bills.”

The word was doubtless in the first place an onomatopoieia, denoting the humming, buzzing sound of wings. Since, however, it was particularly connected with birds, it seems to have been used in the sense of music and song by our Elizabethan poets, and by Milton. Thus:—

“Sweet is the breath of morn, her rising sweet

With charm of earliest birds.”

(Paradise Lost, Book iv. 642.)

And again:—

“Morn when she ascends

With charm of earliest birds.”

(Paradise Lost, Book iv. 651.)

Here, however, in the New Forest, we find the original signification of the word preserved.

Let us further notice one or two more words, which are used by Milton and his contemporaries, and even much later, but which are now found in the Forest, and doubtless elsewhere, as mere provincialisms. Thus, though we do not meet his “tale,” in the sense of number, as in L’Allegro,—

“And every shepherd tells his tale,

Under the hawthorn in the dale;”

—that is, number of sheep: we find its allied word “toll,” to count. “I toll ten cows,” is no very uncommon expression. Then, too, we have the word “tole,” used, as I believe it still is in America, of enticing animals, and thus metaphorically applied to other matters. So, in this last sense, Milton speaks of the title of a book, “Hung out like a toling sign-post to call passengers.”[232]

Again, too, the bat is here called “rere-mouse” (from the Old-English hrere-mus, from hreran to flutter, literally the fluttering mouse, the exact equivalent of the German Flitter-maus[233]), with its varieties rennie-mouse and reiny-mouse,[234] whilst the adjective “rere” is sometimes used, as in Wiltshire, for raw. On the other hand, the word fliddermouse, or, as in the eastern division of Sussex, flindermouse (from the High-German fledermaus), does not, to my knowledge, occur. In the Midland counties it is often known as “leathern wings” (compare ledermus); and thus, Shakspeare, with his large vocabulary, using up every phrase and metaphor which he ever met, makes Titania say of her fairies:—

“Some war with rear-mice for their leathern wings.”

(Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act ii., sc. 3.)

To take a few words common, not only to the New Forest, but to various parts of the West of England, we shall see how strong is the Old-English element here in the common speech. The housewife still baits (betan, literally to repair, and so, when 193joined with fyr, to light) the fire, and on cold days makes it blissy (connected with blysa, a torch). The crow-boy in the spring sets up a gally-bagger (gælan, in its last meaning to terrify), instead of the “maukin” of the north, to frighten away the birds from the seed; and the shepherd still tends his chilver-lamb (cilferlamb) in the barton (bere tun, literally the barley enclosure). The labourer still sits under the lew (hleow, or “hleowð,” shelter, warmth) of the hedge, which he has been ethering (“eðer,” a hedge); and drives the stout (stut, a gadfly) away from his horses; and feels himself lear (lærnes, emptiness), before he eats his nammit (nón-mete), or his dew-bit (deaw-bite).

If we will only open our Bible we shall there find many an old word which could be better explained by the Forest peasants than any one else. Here the ploughman still talks of his “dredge,” or rather “drudge,” that is, oats mixed with barley, just as we find the word used in the marginal reading of Job xxiv. v. 6. Here, too, as in Amos (chap. iv., v. 9), and other places, the caterpillar is called the “palmer-worm.” Here, also, as in other parts of England, the word “lease,” from the Old-English lesan, is far commoner than glean, and is used just as we find it in Wycliffe’s Bible, Lev. xix., 10:—“In thi vyneyeerd the reysonus and cornes fallynge down thou shalt not gedere, but to pore men and pilgrimes to ben lesid thou shalt leeve.” The goatsucker is known, as we have seen, not only as the “jar-bird,” but as the “night-hawk,” as in Leviticus (chap. xi., v. 16) and Deuteronomy (chap. xiv., v. 15); and also the “night-crow,” as we find it called in Barker’s Bible (1616) in the same passages. So also the word “mote,” in the well-known passage in St. Matthew (chap. viii., v. 3), is not here obsolete. The peasant in the Forest speaks of the “motes,” that is, the stumps and roots of trees, in opposition to the 194smaller “mores,” applied also to the fibres of ferns and furze, whilst the sailor on the coast calls the former “mootes,” when he dredges them up in the Channel.[235]

With this I must stop. I will only add that the study of the West Saxon dialect in the counties of Hants, Wilts, and Dorset, is all-important. As we go westward we shall find it less pure, and more mixed with Keltic. As is well known, the Britons lived with the Old-English in perfect harmony in Exeter. Their traces remain there to this day. In these three counties, therefore, are the most perfect specimens of the West-Saxon dialect to be found. Mr. Thorpe has noticed in the Old-English text of Orosius, which is now generally ascribed to Alfred, the change of a into o and o into a, and also the same peculiarity in Alfred’s Boethius.[236] This we have already, in the last chapter, seen to be purely West-Saxon. I have no doubt whatever that at even the present day it is not too late to find other points of similarity, and make still clearer the West-Saxon origin of the Corpus Christi manuscript of the Chronicle,[237] and how far even Alfred and St. Swithin contributed to its pages. These are difficult questions; but I feel sure that much additional light 195can even yet be obtained. Sound criticism would show as much difference between our local dialects, whether even Anglian, or South, or West-Saxon, as between the Doric and Attic of Greece. I have dealt only with the broader features of the Old-English tongue, as it is still spoken in the Forest. Enough, however, I trust, has been shown of the value of provincialisms, even when collected over so limited a space. Everywhere in England we shall find Teutonic words, which are not so much the mould into which all other forms have been cast, as the living germ of our language. Mixed and imbedded with these, as we have also seen, we shall meet Keltic and Romance, by both of which our language has been so influenced and modified. Let us not be ashamed to collect them; for by them we may explain not only obscure passages in our old authors, but doubtful points in our very history.

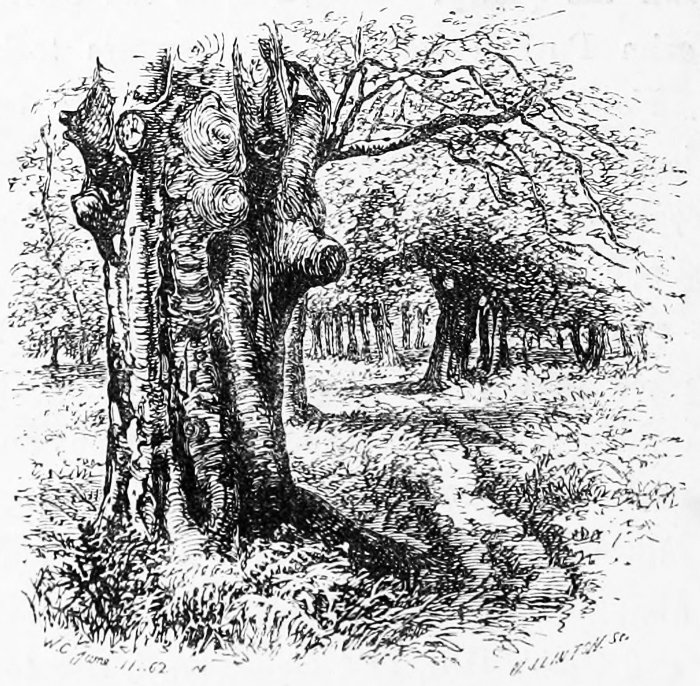

Bushey Bratley (Another View).

CHAPTER XVII.

THE BARROWS.

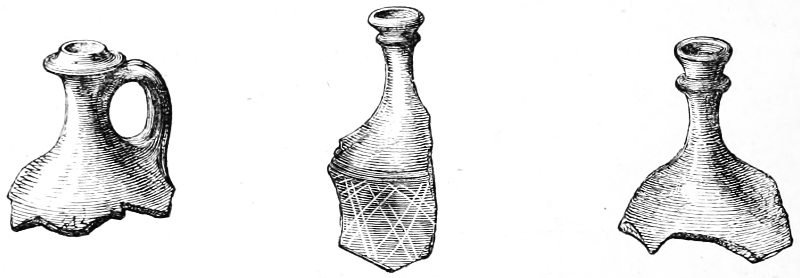

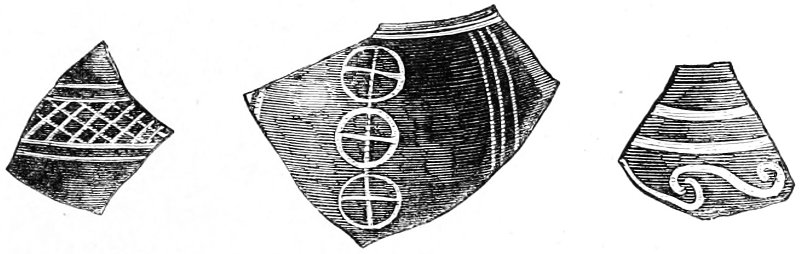

The Urns in Bratley Barrow.

It is much to be regretted that Sir Walter Scott has left no account of his excavations of various barrows in the Forest. However little we may be able to determine by the evidence, or however conjectural the inferences which we may draw, there 197will, at least, be this value to this chapter, that it will put on record facts which otherwise could not be known.

The barrows lie scattered all over the Forest, and are known to the Foresters by the name of “butts,” some of the largest being distinguished by local appellations. As in other parts of England, and as in France, superstition connects them with the fairies; and so we find on Beaulieu Plain two mounds known as the Pixey’s Cave and Laurence’s Barrow.

My own excavations have been entirely confined to the Keltic barrows in the northern part of the Forest.[238] But we will 198first of all take those on Sway and Shirley Commons, opened by Warner.[239] The largest stands a little to the east of Shirley Holms, close to Fetmoor Pond, measuring about a hundred yards in circumference, and surrounded by three smaller mounds varying from thirty to fifty yards, and two more nearly indistinct. These two last are, I suspect, those opened by Warner, where, after piercing the mound, he found on the natural soil a layer of burnt earth mixed with charcoal, and below this, at the depth of two feet, a small coarse urn with “an inverted brim,”[240] containing ashes and calcined bones.

Some more lie to the northward, and are distinguished by being trenched. Two of these also were opened by Warner, but he failed to discover anything beyond charcoal and burnt earth.

His opinion was that these last belonged to the West-Saxons and the former to the Kelts, who were slain defending their country against Cerdic. So large a generalization, however, requires far stronger evidence than can at present be produced.

Warner, too, is besides wrong in much of his criticism, such as that the Teutonic nations never practised urn-burial; whilst the banks in which he sees fortifications may be only the embankments within which dwelt a British population.

Still there is some probability about the conjecture. A little farther down the Brockenhurst stream are Ambrose Hole and Ampress Farm, both names unmistakeably referring to Ambrosius Aurelianus, or Natan-Leod, who led the Britons 199against their invaders. Nearer Lymington, too, stands Buckland Rings,[241] a Roman camp, with its south and north sides still nearly perfect, to which, perhaps, Natan-Leod fell back from Calshot.

All this, however, must be accepted as mere conjecture. A more critical examination of these barrows is still wanting.

Close to them, however, lies Latchmoor or Lichmoor Pond, the moor of corpses, a name which we meet again a little to the westward in Latchmoor Water, which flows by Ashley Common. The words are noticeable, and in connection with Darrat’s (Dane-rout) stream, which is also not far distant may point to a very different invasion.[242]

And now we will pass to the barrows which I have opened. The first are situated on Bratley Plain, as the name shows, a wide heath, marked only by a few hollies and the undulations of the scattered mounds. The largest barrow lies close to the sixth 200milestone on the Ringwood Road. In a straight line to the north, at the distance of a quarter of a mile apart, rise three others, whilst round it on the east side lie a quantity of small circles, so low as hardly to be discernible when the heather is in bloom. An irregularly shaped oval, it rose in the centre to a height of nearly six feet above the ground, measuring sixteen yards in breadth, and twenty-two in length, with a circumference of from sixty to sixty-five. On the south side was a depression from whence the gravel had been obtained. We first cut a trench two yards broad, so as to take the centre, and at about two feet and a half from the surface came upon traces of charcoal, which increased till we reached the floor. A few round stones, probably, as they bore some slight artificial marks, used for slinging, and the flake of, perhaps, a flint knife, were the only things found, and were all placed on the south side. We now cut the mound from east to west, and on the east side, resting on the floor, we discovered the remains of a Keltic urn. The parts were, however, in a most fragile state, and in some instances had resolved themselves into mere clay, and we could only obtain two small fragments, sufficient to show the coarseness and extreme early age of the ware. No charcoal nor osseous matter could be detected adhering to the sides, which, as we shall see, is generally the case.

Round it, as was stated, lie a quantity of small grave-circles, varying from twenty-five to ten yards in circumference, and scarcely better defined than fairy-rings. Two of these I opened, and they corresponded with the mounds on Sway Common examined by Warner, in having a grave about three feet deep, in which we found only charcoal. This was, however, the only point of resemblance, as they had no mound, and contained no urn. One fact is worth noticing, that they were dug in a 201remarkably hard gravelly soil, so hard that the labourers made very slow progress even with their pick-axes. I did not excavate any more, as they were all evidently of the same character. The choice of such a soil, especially with the instruments they possessed, may, perhaps, show the importance which the Britons attached to the rite of burial.

About a quarter of a mile, or rather less, from this great graveyard lay a solitary mound, two feet and a half in height, having a circumference of twenty-seven feet, a very common measurement, but without any trench. Upon digging into it on the east side we quickly came, about four inches from the surface, upon a patch of charcoal and burnt earth. Proceeding farther, we reached two well-defined layers of charcoal, the uppermost two feet from the top of the barrow. A band of red burnt earth, measuring five inches, separated these two beds, in both of which in places appeared white spots and patches of limy matter, the remains of calcined bones. In the centre, as shown in the illustration, we found a Keltic urn. Imbedded in a fine white burnt clay, which had hardened, placed with its mouth uppermost, and ornamented with a rough cable-moulding, and two small ears, it stood on the level of the natural soil, rising to within sixteen inches of the top of the mound.

Digging on both sides, we discovered two more urns imbedded in the same hard white sandy clay, so hard that it had to be scraped away with knives. Like the first, they were made by hand, and when exposed quite shone with a bright vermilion, which quickly changed to a dull grey. The paste, however, was a light yellow, mixed with coarse gritty sand. And the three were placed, as shown by the compass, exactly due north-east and south-west.

A plain moulding ran round the south-west urn, which was 202considerably smaller and not so well baked as the other two, and had very much fallen to pieces from natural decay. This was placed eight inches lower than the central urn.

The northernmost was the same size as the central, though differing from it in the contraction of the rim, and when discovered was perfectly whole, but was unfortunately fractured by being separated from a large furze root, which had completely twined round the upper part. It, too, was placed on a lower level, by four inches, than the central urn. The two extreme urns were exactly five feet apart, and the interiors of them all were blackened by the carbon from the charcoal, burnt earth, and bones, which they contained.

Looking at their rude forms and large size, their straight sides, their wide mouths, the thickness, and the rough gritty texture of the paste,[243] the absence of nearly all ornamentation, and, with the exception, perhaps, of a slinging stone, of all weapons, we shall not be wrong in dating them as long anterior 203to the Roman invasion—how long a more minute criticism and a greater accumulation of facts than is now possessed, can alone determine.

There are, however, one or two points peculiarly noticeable about this barrow—first, the enormous quantity of burnt earth, suggesting that the funeral pyre was actually lit on the spot, which certainly was not the case in most of the other barrows, where the charcoal is only sprinkled here and there, or appears in the form of a small circular patch on the floor. Secondly, the two bands of charcoal, so full of osseous matter, would certainly go far to prove, what has been surmised by Bateman and others, that the slaves or prisoners were immolated at the decease of their master or conqueror.

Again, too, the different sizes and positions of the urns may, perhaps, indicate either degrees of relationship or rank of the persons buried. And this theory is somewhat corroborated by the contents. The central urn was examined on the spot, and, like all the others, with the exception of a round stone slightly indented, contained burnt earth, limy matter, and at the bottom the larger bones, which were less calcined, but which, owing to the want of proper means, we could not preserve. The other two were opened at the British Museum. At the bottom of the north-easternmost were also placed bones in a similar condition, amongst which Professor Owen recognized the femur and radius of an adult. The smallest urn also showed bones placed in the same manner at the bottom, but in this case smaller, and amongst them Professor Owen determined processus dentatus, and the body of the third cervical vertebra, and was of opinion that they were those of a person of small stature, or, perhaps, of a female. This is what might have been expected. And the fact of their being put in the 204smallest vessel, which, as we have noticed, was placed below the level of the others, certainly indicates a distinction made in the mode of burial of persons of either different ages or sexes.

The fact, too, that all the larger bones were placed by themselves at the bottom is worth noticing, and shows that they must have been carefully collected and separated from the burnt earth and charcoal of the pyre.

About another quarter of a mile off rise two more barrows, measuring exactly the same in circumference as the last, though not nearly so high, being raised only sixteen inches above the ground. Upon opening the southernmost, we soon came, on the east side, upon traces of charcoal, which increased to a bed of an inch and a half in thickness as we reached the centre. Here we found an urn of coarse pottery exactly similar in texture to those in the previous barrow. It was, however, in such a bad state of preservation, and so soft, from the wetness of the ground, that the furze-roots had grown through the sides, and it crumbled to bits on being touched. Some few pieces, though, near the bottom, we were able to preserve. Its shape, however, was well shown by the form which its contents had taken. It seems to have been, though much smaller, exactly of the same rude, straight-sided, and wide-mouthed pattern as the other urns, measuring seven inches in height, and in circumference, near the top, two feet two inches, and at the bottom, one foot four inches. The cast was composed entirely of burnt stones, and black earth, and osseous matter, reduced to lime, in which the furze-roots had imbedded themselves.

The fellow barrow, which was only about fifty yards distant, and whose measurements were exactly the same, contained also charcoal, though not in such large quantities, and fragments 205of an urn placed not in the centre, but near the extreme western edge. The remains here were in a still worse state of decomposition, and we could obtain no measurements, but only one or two pieces of ware, which, in their general coarseness and grittiness of texture, corresponded with the others, and not only showed their Keltic manufacture, but their extreme early date.[244]

This last mound, I may add, was composed of gravel, whilst the other was made simply of mould: and two depressions on the heath showed where the material had been obtained.

About two miles to the north-east, close to Ocknell Pond, lies a single barrow of much the same size as these two, though a great deal higher, being raised in the centre to three feet and a half. We began the excavation on the east side, proceeding to the centre, but found nothing except some charcoal, and peculiarly-shaped rolled flints, placed on the level of the ground.

We then made another trench from the north side, and close to some charcoal, about a foot and a half below the raised surface, came upon the neck of a Roman wine vessel (ampulla). Although we opened the whole of the east side, we could not find the remaining portion. The barrow bore no traces of having been previously explored, nor did the soil appear to have been moved. The fracture was certainly not recent, and it is very possible that some disappointed treasure-seekers in the 206Middle Ages had forestalled us, and time had obliterated all their marks in opening the mound.

Neck of Roman Wine Vessel, Keltic Urn, and Flint Knives.

From the position of the vessel at the top of the barrow, there had evidently been a second interment. The remains, however, are in accordance with what we might have expected. The barrow is situated not far from the Romano-British potteries of Sloden, and close to it run great banks, known as the Row-ditch, marking, in all probability, the settlements of a Romano-British population.[245]

On Fritham Plain, not far from Gorely Bushes, lies another vast graveyard. The grave-circles are very similar in size to those round the large barrow on Bratley Plain, though a good deal higher, with, here and there, some oval mounds ranged side by side, as in a modern churchyard. In the autumn of 1862, I opened five of these, with the same result of finding charcoal in all, though placed in different parts, but in all instances resting on the natural ground, and giving evidence of only one interment. As in other cases, the grave-heaps were often alternately composed of mould and gravel. No traces of urns or celts were found, but in one or two a quantity of small circular stones, with indistinct marks of borings, which could hardly have accidentally collected.

About a quarter of a mile off, on the road to Whiteshoot,[246] lies, however, a square mound, measuring nine yards each way, and averaging a foot and a half in height. On opening it on the north side, we came upon the fragments of an urn, but so much decayed that we could only tell that they were, probably, Keltic. On the west side, another trench, which had been made, showed the presence of charcoal, which kept increasing till we reached the centre, where we found what appeared to be the remains of three separate urns, placed in a triangle at about a yard apart. These also were in the 208same decayed state, and crumbled to pieces as we endeavoured to separate them from the soil. With some difficulty we managed to preserve a few fragments which were identical with those which had been previously discovered in the other barrows at Bratley. They contained, like most of the other vessels, burnt stones and white osseous matter reduced to lime. There seems, however, to have been some difference in their texture with that of the fragments found on the north side, which were less gritty and coarse, and which bore no traces of charcoal or lime.[247]

We will now leave Fritham, and cross Sloden and Amberwood Plantation. Not far from Amberwood Corner, and above Pitt’s Enclosure, stand two barrows. The largest was opened thirty years ago by a labouring man, who, to use his own language, “constantly dreamt that he should there find a crock of gold.” His opening was rewarded by discovering only some charcoal. In 1851, the Rev. J. Pemberton Bartlett also explored it with still less success. It is, however, a remarkable barrow, and differs in character from any of the preceding, being composed in the interior of large sub-angular flints, and cased on the outside with a rampart of earth. Beyond it lies another, very different in style, being made only of earth. This was also opened by Mr. Bartlett, who found some pieces of charcoal, and small fragments of a very coarsely-made urn.

About a mile away on Butt’s Plain rise five more barrows, and beyond them again two more. Of the first five, two were explored by Mr. Bartlett, who was unsuccessful, and two by myself.

The two which I opened lie on the right of the track leading from Amberwood to the Fordingbridge road. The northernmost was considerably the largest, having a circumference of fifty yards, and was composed simply of gravel and earth. In it we found only a circle of charcoal placed nearly in the centre on the level of the ground.

The other was more remarkable. It measured only thirty yards in circumference, but was composed in the centre of raised earth, above which were piled large rolled flints, making a stratum of from two to three feet in depth on the sides, but gradually becoming thinner as it reached the centre, which was barely covered. It thus totally differed from that near Amberwood, where the earth flanked the stones instead of being the nucleus round which they were placed. In it we found a circle of charcoal ingrained with limy matter, a few remains of much calcined bones, and a fine stone hammer bored with two holes slantwise, to give a greater purchase to the handle.

Besides these, I opened a solitary barrow situated between Handycross Pond and Pinnock Wood, close to Akercombe Bottom. It measured twenty-seven yards in circumference, and three feet in height. After digging into it near the centre, we found in the white sand, of which the mound was chiefly composed, a good deal of charcoal on and below the level of the ground, but failed to discover any traces of an urn, although we went down to a considerable depth.

Further, a solitary oval mound stood on the south side of South Bentley, half way between it and Anses Wood. It 210measured two feet and a half in height, twelve yards in length, and seven in breadth. This also I opened, but failed to find even any remains of charcoal, and, from the easy-moving nature of the soil, am inclined to suspect that it was modern, and raised for some other purpose than that of burial. On the east side was a depression filled with water, from whence the soil was taken.

The most remarkable barrow, if it can be so called, in this part of the Forest, is at Black Bar, at the extreme west end of Linwood, measuring nearly four hundred yards in circumference, and rising to the height of forty feet or more. It is evidently in part factitious, for upon sinking a pit ten feet deep we reached charcoal mixed with Roman pottery, but not of a sepulchral character.

In its general appearance the mound is not unlike the famous Barney Barn’s Hill, in Dibden Bottom, and close to it rises another, known as the Fir Pound, not much inferior in size. I made other openings on the top and sides, but discovered nothing further. To excavate it thoroughly would require an enormous time, and would in all probability not repay the labour. It looks, however, by the depressions on the summit, as if it had once been the site of Keltic dwellings. And this is in some measure corroborated by a small mound close to it, where, as if apparently left or thrown away, we found placed in a hole a small quantity of extremely coarse pottery—the coarsest and thickest which I have ever seen. Again, too, in a field close by, known as Blackheath Meadow, we everywhere met traces of Romano-British ware, very similar in shape and texture to that in Sloden, described in the next chapter.

The whole district just round here is most interesting. 211About a mile to the north is Latchmoor Stream and Latchmoor Green, marking, doubtless, some burial-ground; and not far off stands one of those elevated places, common in the Forest, with the misleading title of Castle.

I must not, too, forget to mention some barrows on Langley Heath, just outside the present eastern boundary of the Forest, and especially interesting from being situated so near to Calshot, where, as we have seen, Cerdic probably landed. Seven of them were opened by the Rev. J. Pemberton Bartlett. The mounds, averaging about twenty yards in circumference, were, in some cases, slightly raised, as much as a foot and a half, though in others nearly on a level with the natural surface of the soil. In them all was found a single grave, though, in one instance, two, running about three feet in depth, and containing only burnt earth and charcoal. They thus exactly corresponded, with the exception of the slight mound, with those on Bratley Plain.

With this we must conclude.[248] It would not be difficult to 212frame some theory from these results. I, however, here prefer to allow the simple facts to remain. As we have seen, the barrows in this part of the Forest, like all others of the same period, contained nothing, with the exception of the single stone-hammer, and the slinging pebbles, and the flake of flint, but nearly plain urns, full of only burnt earth, charcoal, and human bones. No iron, bronze, nor bone-work of any sort, was found, which would still further go to prove their extreme early age. Curiously enough, too, no teeth, bones, nor horn-cores of animals were discovered, as so often are in Keltic barrows.[249] Like all others, too, of an early date, there seem to have been several burials in the same grave, though this, as on Fritham Plain, is very far from being always the case. Some little regularity evidently prevailed with the different septs. Some, as at Bratley, placed the charred remains in a grave from two to three feet in depth; others, as at Butt’s Plain, on the mere ground. On the other hand, a good deal of caprice seems to have been exercised as to the materials with which each barrow was formed, and the way and the shape in which it was built, as also the arrangement of the charcoal.

Further, perhaps, the different grades of life and relationship were marked by the presence and position of the urns. 213Whether this be so or no, it is certain that the mounds here which contained mortuary vessels were, as a rule, more elevated, and in nearly all instances placed by themselves. The fact, too, of the cube-shaped mound with its remains of four urns should be kept in mind.

Little more can with certainty be said. The flint knives which have been picked up in the Forest, the stone hammer in the grave, the clumsy form and make of the urns, the places, too, of burial—in the wide furzy Ytene, in after-times the Bratleys, and Burleys, and Oakleys, of the West-Saxons—all show a people whose living was gained rather by hunting than agriculture or commerce.

Barrows on Beaulieu Plain.

CHAPTER XVIII.

THE ROMAN AND ROMANO-BRITISH POTTERIES.

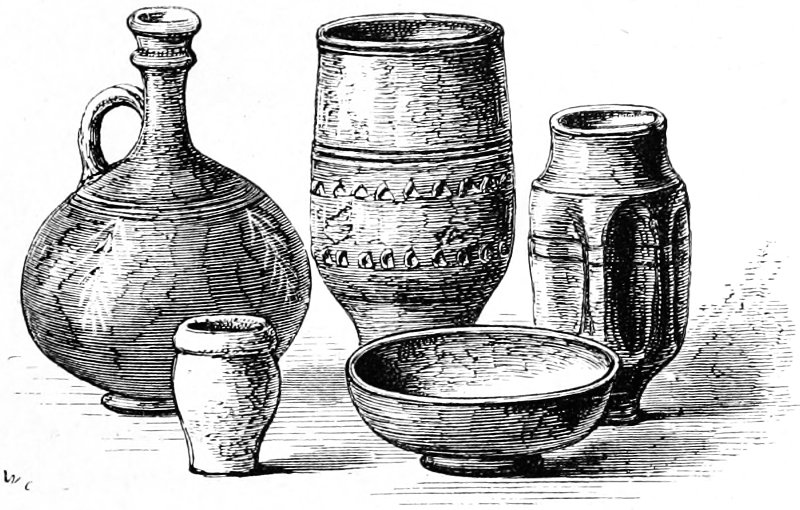

Wine-Flask, Drinking-Cups, and Bowls.

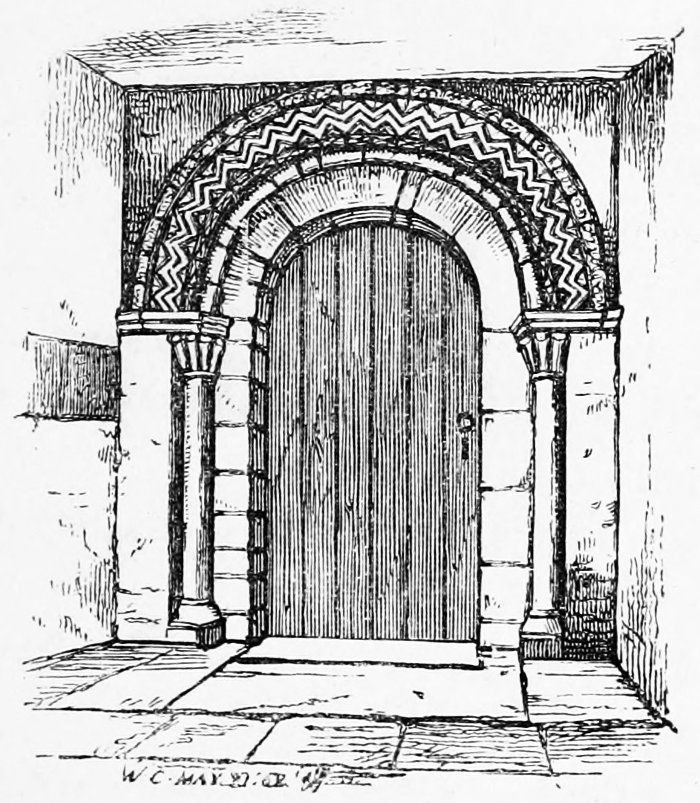

From time to time the labourer, in draining or planting in the Forest, digs down upon pieces of earthenware, whilst in the turfy spots the mole throws up the black fragments in her mound of earth. The names, too, of Crockle—Crock Kiln—and Panshard Hill, have from time immemorial marked the site of at least two potteries. Yet even these had escaped all notice until Mr. Bartlett, in 1853, gave an account of his excavations, and showed the large scale on which the Romans carried on 215their works, and the beauty of their commonest forms and shapes.[250]

Since then both Mr. Bartlett and myself have at different times opened various other sites, and some short notice of their contents may, perhaps, not be without interest.

Fifty years ago, when digging the holes for the gate-posts at the south-west corner of Anderwood Enclosure, the workmen discovered some perfect urns and vases. These have, of course, long since been lost. But as the place was so far distant from the potteries at Crockle, I determined to re-open it. The site, however, had been much disturbed. Enough though could be seen to show that there had once been a small kiln, round which were scattered for three or four yards, in a black mould of about a foot and a half in depth, the rims, and handles, and bottoms of vessels of Romano-British ware. The specimens were entirely confined to the commonest forms, all ornamentation being absent, and the ware itself of a very coarse kind, the paste being grey and gritty.

About a mile and a half off, in Oakley Enclosure, close to the Bound Beech, I was, however, more fortunate. Here the kiln was perfect. It was circular, and measured six yards in circumference, its shape being well-defined by small hand-formed masses of red brick-earth. The floor, about two feet below the natural surface of the ground, was paved with a layer of sand-stones, some of them cut into a circular shape, so as to fit the kiln, the upper surfaces being tooled, whilst the under remained in their original state. As at Anderwood, the ware was broken into small fragments, and was scattered round the kiln for five or six yards. The specimens were here, too, of 216the coarsest kind, principally pieces of bowls and shallow dishes, and, perhaps, though of a different age, not so unlike as might at first sight be supposed to the

“Sympuvium Numæ, nigrumque catinum,

Et Vaticano fragiles de monte patellæ.”

These appear to be the only kilns which, perhaps from the unfitness of the clay, were worked in this part of the Forest, and were used only in manufacturing the most necessary utensils in daily life.

Of far greater extent are the works at Sloden, covering several acres. All that remains of these, too, are, I am sorry to say, mere fragments of a coarse black earthenware. And although I opened the ground at various points, I never could meet with anything perfect. Yet the spot is not without great interest. The character and nature of the south-western slope exactly coincide with Colt Hoare’s description of Knook Down and the Stockton Works.[251] Here are the same irregularities in the ground, the same black mould, the same coarse pottery, the same banks, and mounds, and entrenchments, all indicating the settlement of a Romano-British population. Half-way down the hill, not far from two large mounds marking the sites of kilns, stretch trenches and banks showing the spaces within which, perhaps, the potters’ huts stood, or where the cultivated 217fields lay, whilst at one place five banks meet in a point, and between two of them appear some slight traces of what may have been a road.[252]

At the bottom of the hill, but more to the south-westward, stands the Lower Hat, where the same coarse ware covers the earth, and where the presence of nettles and chickweed shows that the place has once been inhabited.

The Crockle and Island Thorn potteries lie about a mile to the north-east. At Crockle there were, before Mr. Bartlett opened them, three mounds, varying in circumference from one hundred and eighty to seventy yards, each, as I have ascertained, containing at least three or four, but probably more, kilns. As the lowest part of the smallest and easternmost mound had not been entirely explored, I determined to open this piece. 218Beginning at the extremity, we soon came upon a kiln, which, like the others discovered by Mr. Bartlett, only showed its presence by the crumbling red brick earth. An enormous old oak-stump had grown close beside it, and around the bole were heaped the drinking-vessels and oil-flasks, which its now rotten roots had once pierced.

Necks of Oil-Flasks.

Necks of Wine-Vessels and Oil-Flask.

Nothing could better show, as the excavation proceeded, the former state of the works. Here were imbedded in the stiff yellow putty-like clay, of which they were made, masses of earthenware, the charcoal, with which they were fired, still sticking to their sides—pieces of vitreous-looking slag, and a grey line of cinders mixed with the red brick earth of the kiln. The ware remained just as it was cast aside by the potter. You might tell by the bulging of the sides, and the bright metallic glaze of the vessels, how the workman had overheated the kiln;—see, too, by the crookedness of the lines, 219where his hand had missed its stroke. All was here. The potter’s finger-marks were still stamped upon the bricks. Here lay the brass coin which he had dropped, and the tool he had forgotten, and the plank upon which he had tempered the clay.[253]

The Island Thorn potteries had been so thoroughly opened by Mr. Bartlett, that I there made but little further explorations, and must refer my readers to his account,[254] only here adding that the ware scarcely differed, except in shape and patterns, from that at Crockle.

About a mile westward stands Pitt’s Enclosure, where in three different places rise low mounds, two of which, since the publication of his account, have been opened by Mr. Bartlett, but from which he only obtained fragments.

The third, which I explored in 1862, was remarkable for the number of kilns placed close together, separated from each other only by mounds of the natural soil. In all, there were five, ranged in a semicircle, and paved with irregular masses of sandstone. They appear to have been used at the time at which they were left for firing different sorts of ware. Close to the westernmost kiln, we found only the necks of various unguent bottles, whilst the easternmost oven seems to have been employed in baking only a coarse red panchion, on which a cover (operculum), with a slight knob for a handle, fitted. Of these last we discovered an enormous quantity, apparently flung away into a deep hole.

Near the central kilns we found one or two new shapes and patterns, but they were, I am sorry to say, very much broken, the ware not being equal in strength or fineness to that at Crockle. The most interesting discovery, however, were two distinct heaps of white and fawn-coloured clay and red earth, placed ready for mixing, and a third of the two worked together, fit for the immediate use of the potter.

Near to these works stretch, on a smaller scale, the same 221embankments which mark the Sloden potteries. One is particularly noticeable, measuring twenty-two feet in width, and running in the shape of the letter Z. In the central portion I cut two trenches, but could discover nothing but a circle of charcoal, looking as if it was the remains of a workman’s fire, placed on the level of the natural soil. Another trench I opened at the extreme end, as also various pits near the embankment, but failed to find anything further.

At Ashley Rails, also, close by, stand two more mounds, which cover the remains of more ware. These I only very partially opened, for the black mould was very shallow, and the specimens the same as I had found in Pitt’s Wood.

Besides these, there are, as mentioned in the last chapter, extensive works at Black Heath Meadow at the west-end of Linwood, but they are entirely, like those in Sloden, Oakley, and Anderwood, confined to the manufacture of coarse Romano-British pottery. This last ware seems to differ very little in character or form. The same shapes of jars (copied from the Roman lagenæ) were found by Mr. Kell near Barnes Chine in the Isle of Wight,[255] though at Black Heath, as in the other places in the Forest, handles, through which cords were probably intended to pass, with flat dishes, and saucer-like vessels (shaped similar to pateræ), all, however, in fragments, occurred.[256]

Such is a brief account of the potteries in the Forest. Their extent was, with two exceptions, restricted to one district, where the Lower Bagshot Sands, with their clays, crop out, and to the very same bed which the potters at Alderholt, on the other side of the Avon, still at this hour work.

The two exceptions at Oakley and Anderwood are situated just at the junction of the Upper Bagshot Sands and the Barton Clays, which did not suit so well, and where the potteries are very much smaller, and the ware coarser and grittier.

The date of the Crockle potteries may be roughly guessed by the coins, found there by Mr. Bartlett, of Victorinus.[257] These were much worn, and, as Mr. Akerman suggests, might be lost about the end of the third century; but the potteries were probably worked till or even after the Romans abandoned the island.

There is nothing to indicate any sudden removal, but, on the contrary, everything shows that the works were by degrees stopped, and the population gradually withdrew. None of the vessels are quite perfect, but are what are technically known as “wasters.” The most complete have some slight flaw, and are evidently the refuse, which the potter did not think fit for the market.

The size of the works need excite no surprise, when we 223remember how much earthenware was used in daily life by the Romans—for their floors, and drinking-cups, and oil and wine flasks, and unguent vessels, and cinerary urns, and boxes for money. The beauty, however, of the forms, even if it does not approach that of the Upchurch and Castor pottery, should be noticed. The flowing lines, the scroll-work patterns, the narrow necks of the wine-flasks and unguent vessels, all show how well the true artist understands that it is the real perfection of Art to make beauty ever the handmaid of use.

Patterns from Fragments.

Another thing, too, is worthy of notice, that the artist was evidently unfettered by any given pattern or rule. Whatever device or form was at the moment uppermost in his mind, that he carried out, his hand following the bent of his fancy. Hence the endless variety of patterns and forms. No two vessels are exactly alike. In modern manufactures, however, the smooth 224uniformity of ugliness most admirably keeps down any symptoms of the prodigal luxuriance of beauty.[258]

We must, however, carefully beware of founding any theory, from the existence of these potteries, that the Forest must therefore have been cultivated in the days of the Conqueror. The reason why the Romans chose the Forest is obvious,—not from its fertility, but because it supplied the wood to fire the kilns; the same cause which, centuries after, made Yarranton select Ringwood for his smelting-furnaces. We must, too, bear in mind that after the Romans abandoned the island the natives soon went back to their primitive state of semi-barbarism; and further, that the interval between the Roman occupation and the Norman Conquest was nearly as great as that between ourselves and the Conqueror—a period long enough for the Kelts, and West-Saxons, and Danes to have swept away in their feuds all traces of civilization.

But what we should see in them is that beauty of form, which in simple outline has seldom been excelled, proclaiming a people who should in their descendants be the future masters of Art, as then they were of warfare.

The history of a nation may be more plainly read by its manufactures than by its laws or constitution. Its true æsthetic life, too, should be determined not so much by its list 225of poets or painters, as by the beauty of the articles in daily use.

And so still at Alderholt, not many miles off, the same beds of clay are worked, and jars, and flasks, and dishes made, but with a difference which may, perhaps, enable us to understand our inferiority in Art to the former rulers of our island.

What further we should see in the whole district, is the way in which the Romans stamped their iron rule upon every land which they conquered. Everywhere in the Forest remain their traces. Urns, made at these potteries, full of their coins, have been dug up at Anderwood and Canterton. Nails at Cadenham, millstones at Studley Head, bricks at Bentley, iron slag at Sloden, with the long range of embankments stretching from wood to wood, and the camps at Buckland Rings and Eyeworth, show that they well knew both how to conquer in war and to rule in peace.

Oil-Flask, Drinking-Cups, Bowl, and Jar

CHAPTER XX.

THE GEOLOGY.

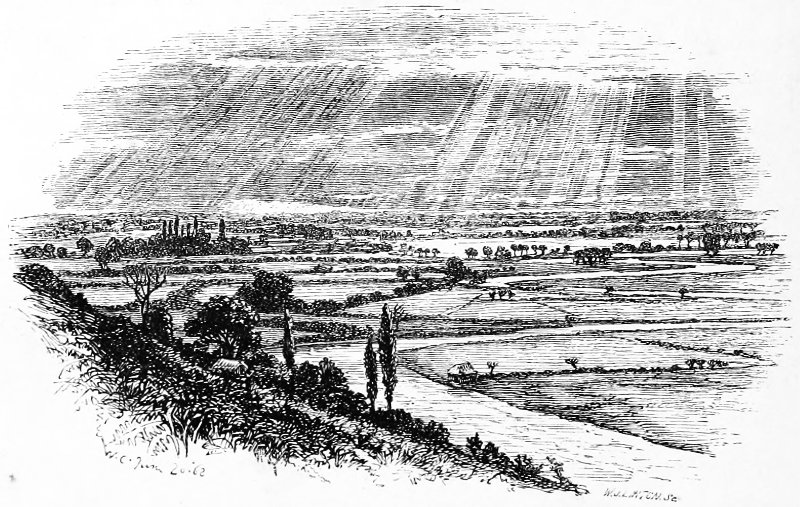

The Barton Cliffs.

I have endeavoured, whenever there was an opportunity, to point out the natural history of the Forest, feeling sure that, from a lack of this knowledge, so many miss the real charms of the 235country. “One green field is like another green field,” cried Johnson. Nothing can be so untrue. No two fields are ever the same. A brook flowing through the one, a narrow strip of chalk intersecting the other, will make them as different as Perthshire from Essex. Even Socrates could say in the Phædrus, τὰ μὲν οὖν χωρία καὶ τὰ δένδρα οὐδέν μ’ ἐθέλει διδάσκειν. and this arose from the state, or rather absence, of all Natural Science at Athens. Had that been different he would have spoken otherwise.

The world is another place to the man who knows, and to the man who is ignorant of Natural History. To the one the earth is full of a thousand significations, to the other meaningless.

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.