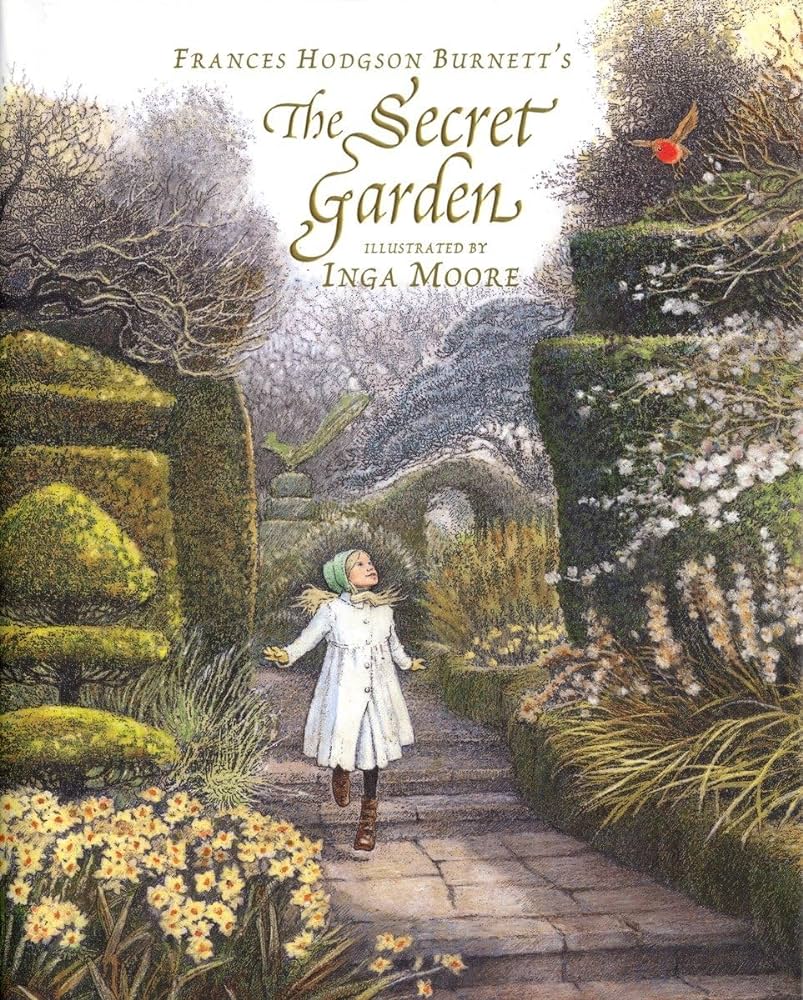

Illustrated by Inga Moore

Jacki Kellum Notes on The Secret Garden

During Chapter 3 of The Secret Garden, we begin to see glimmers of light.

If you remember, in Chapter 2 of The Secret Garden, Mary was dressed all in black and while she was riding in a carriage toward the gloomy Misselthaite Manor, rain added to the dark mood of the story, and Mary fell asleep.

In Chapter 3, Mary wakes up — both literally and figuratively:

“She slept a long time, and when she awakened…” It was still raining, but “The guard lighted the lamps in the carriage….”

If we might assume that sleep is a type of avoidance, waking is a major step toward seeing what is happening. But also, the guard turned on the lights.

To borrow lyrics of a familiar hymn–

“I saw the light, I saw the lightNo more darkness, no more nightNow I’m so happy no sorrow in sightPraise the Lord, I saw the light.”

Like the weary wanderer in the above hymn, Mary has been awakened to a new light. Let the healing begin.

After another brief nap, Mary is coaxed into awakening and Mary assumes a new type of alertness.

“You have had a sleep!” she said. “It’s time to open your eyes! We’re at Thwaite Station and we’ve got a long drive before us.”When he shut the door, mounted the box with the coachman, and they drove off, the little girl [Pg 25]found herself seated in a comfortably cushioned corner, but she was not inclined to go to sleep again. She sat and looked out of the window, curious to see something of the road over which she was being driven….”

The theme of darkness versus light is one of the most used literary themes of all time.

“You’re out of the woods,you’re out of the dark, you’re out of the night,Step into the sun, step into the light.”

In The Hobbit, the grotesque creature Gollum lives in a dark cave:

The fair-haired Luke Skywalker battles the Dark Darth Vader:

If you subscribe to the teaching of the Bible, you might recall that the struggle toward the light was in the first chapter of the Bible. Initially, the world was dark—

But immediately, before He created anything else, God created Light!

Later, God created Night and Day, but initially and most importantly, he created the Light.

If you are suspicious of words in the Bible, it might be of interest for you to know that the Ancient Greeks believed that the world came into being in about the same way: Light was also of importance in that story:

Darkness versus Light is a theme in much of literature–even in children’s literature:

The fact that Mary has “opened her eyes” at the beginning of Chapter 3 of The Secret Garden does not mean that Mary’s darkness has entirely ended. Mary must make a difficult journey to overcome all her darkness and crossing the Moor is one of her first tasks.

The Moor is an actual place in England, and it became the setting for more than one literary piece.

The fictional Misselthwaite Manor was in Yorkshire, where the real authors the Brontë sisters lived. The Secret Garden was published in 1911, the Brontë sisters wrote about the Moors in the 1800s.

“The authors perhaps most responsible for turning the English moors into an iconic Gothic setting were the Brontë sisters. Charlotte Brontë and her siblings were raised in West Yorkshire and spent much of their childhood exploring the surrounding moorland. Charlotte and her sisters would stay in the area all their lives, so it makes sense that the environment they loved so much would find its way into their writings. Charlotte Brontë’s titular protagonist of her 1847 novel Jane Eyre is quite closely associated with the moors. As a child, Jane is raised on tales from her nursemaid of fairies and imps that make their homes on the moors. At Thornfield, Mr. Rochester affectionately refers to Jane as a “fairy,” “elf,” and “sprite,” as if she were a supernatural creature that wandered into his home from the wild moors. Indeed, Jane and Rochester first meet out on the moors when Rochester experiences their danger for himself after his horse slips on a patch of ice, leaving him injured and far from civilization as darkness descends. Luckily, Jane is there to rescue him and help him back onto his horse. The moors are also where Jane retreats to for meditation and self-reflection. And, of course, after learning that marrying Rochester would involve committing the sin of bigamy, Jane flees out onto the moors in the middle of the night and wanders without food or shelter, sleeping out in the open, until she comes upon the aptly named Moor House. It is here that Jane finds family and fortune, gaining confidence and power until she is ready to meet Rochester again as his equal. In Jane Eyre, the moors represent everything from the mysterious realm of the supernatural, to a peaceful refuge, to the inhospitable wilds.

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

“The moors feature prominently in a novel by another Brontë sister, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847). … the moors in Wuthering Heights represent a liminal space between the two homes, Thrushcross Grange and Wuthering Heights, and its wildness allows it to be a place where the boundaries of society are crossed and Cathy and Heathcliff can indulge in a relationship that transcends social class. Heathcliff, specifically, is closely identified with the moors, as you can tell by his very name including the synonym “heath.” His moods are tempestuous, like the “wuthering” wind storms that the moors are known for. Like the elfin Jane, Heathcliff is often compared to a supernatural being—in this case, not an alluring fairy creature but a devil or an “imp of Satan.” And the moors are where the supernatural makes its home, as evidenced particularly by the story’s ghosts. Cathy’s ghost seems to drift in from the moors to scratch at the windows of Wuthering Heights, and she seems to bring Heathcliff’s soul out with her at the end of the novel. As ghosts, Cathy and Heathcliff return to the moors where they loved to roam together as children. The moors here represent freedom, unrestrained passion, and the supernatural.” The Gothic Library

In the Secret Garden, the Moor is a wild and windy obstacle through which Mary Lennox must pass to successfully complete her journey.

“At last the horses began to go more slowly, as if they were climbing up-hill, and presently there seemed to be no more hedges and no more trees. She could see nothing, in fact, but a dense darkness on either side. She leaned forward and pressed her face against the window just as the carriage gave a big jolt.

“Eh! We’re on the moor now sure enough,” said Mrs. Medlock.

The carriage lamps shed a yellow light on a rough-looking road which seemed to be cut through bushes and low growing things which ended in the great expanse of dark apparently spread out before and around them. A wind was rising and making a singular, wild, low, rushing sound.

“It’s—it’s not the sea, is it?” said Mary, looking round at her companion.

“No, not it,” answered Mrs. Medlock. “Nor it isn’t fields nor mountains, it’s just miles and miles and miles of wild land that nothing grows on but heather and gorse and broom, and nothing lives on but wild ponies and sheep.” Burnett

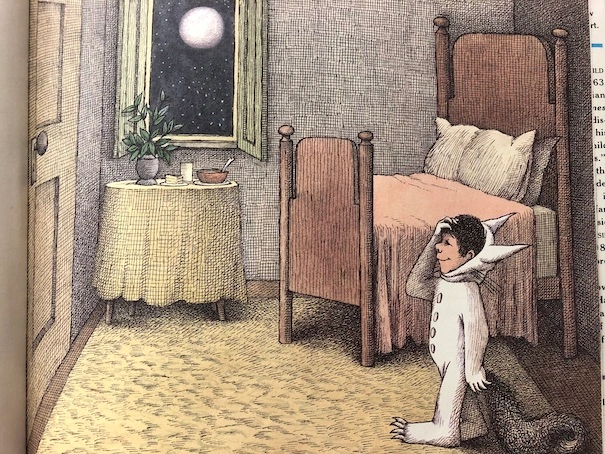

Especially since Mary thought that the Moors was an ocean over which they were passing I see a similarity between the Moors as a passage in The Secret Garden, and the sea over which Max passed in Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are:

“That very night in Max’s room a forest grew

and grew –

and grew

and grew until his ceiling hung with vines and the walls became the world all aroundand an ocean tumbled by with a private boat for Max

and he sailed off through night and dayand in and out of weeks

and almost over a year

to where the wild things are,” – Where the Wild Things Are

At this point, Max’s journey is only partially complete. After he spent time in the land of the Wild Things, he became bored and had to sail back home:

When he arrived back at home, he discovered his supper was still waiting for him.

This part of Where the Wild Things Are seems very much like Mary’s journey to Missethaite Manor:

“And then Mary Lennox was led up a broad staircase and down a long corridor and up a short flight of steps and through another corridor and another, until a door opened in a wall and she found herself in a room with a fire in it and a supper on a table.” Burnett

CHAPTER III

ACROSS THE MOOR

She slept a long time, and when she awakened Mrs. Medlock had bought a lunchbasket at one of the stations and they had some chicken and cold beef and bread and butter and some hot tea. The rain seemed to be streaming down more heavily than ever and everybody in the station wore wet and glistening waterproofs. The guard lighted the lamps in the carriage, and Mrs. Medlock cheered up very much over her tea and chicken and beef. She ate a great deal and afterward fell asleep herself, and Mary sat and stared at her and watched her fine bonnet slip on one side until she herself fell asleep once more in the corner of the carriage, lulled by the splashing of the rain against the windows. It was quite dark when she awakened again. The train had stopped at a station and Mrs. Medlock was shaking her.

“You have had a sleep!” she said. “It’s time to open your eyes! We’re at Thwaite Station and we’ve got a long drive before us.”

Mary stood up and tried to keep her eyes open [Pg 24]while Mrs. Medlock collected her parcels. The little girl did not offer to help her, because in India native servants always picked up or carried things and it seemed quite proper that other people should wait on one.

The station was a small one and nobody but themselves seemed to be getting out of the train. The station-master spoke to Mrs. Medlock in a rough, good-natured way, pronouncing his words in a queer broad fashion which Mary found out afterward was Yorkshire.

“I see tha’s got back,” he said. “An’ tha’s browt th’ young ‘un with thee.”

“Aye, that’s her,” answered Mrs. Medlock, speaking with a Yorkshire accent herself and jerking her head over her shoulder toward Mary. “How’s thy Missus?”

“Well enow. Th’ carriage is waitin’ outside for thee.”

A brougham stood on the road before the little outside platform. Mary saw that it was a smart carriage and that it was a smart footman who helped her in. His long waterproof coat and the waterproof covering of his hat were shining and dripping with rain as everything was, the burly station-master included.

When he shut the door, mounted the box with the coachman, and they drove off, the little girl [Pg 25]found herself seated in a comfortably cushioned corner, but she was not inclined to go to sleep again. She sat and looked out of the window, curious to see something of the road over which she was being driven to the queer place Mrs. Medlock had spoken of. She was not at all a timid child and she was not exactly frightened, but she felt that there was no knowing what might happen in a house with a hundred rooms nearly all shut up—a house standing on the edge of a moor.

“What is a moor?” she said suddenly to Mrs. Medlock.

“Look out of the window in about ten minutes and you’ll see,” the woman answered. “We’ve got to drive five miles across Missel Moor before we get to the Manor. You won’t see much because it’s a dark night, but you can see something.”

Mary asked no more questions but waited in the darkness of her corner, keeping her eyes on the window. The carriage lamps cast rays of light a little distance ahead of them and she caught glimpses of the things they passed. After they had left the station they had driven through a tiny village and she had seen whitewashed cottages and the lights of a public house. Then they had passed a church and a vicarage and a little shop-window or so in a cottage with toys and [Pg 26]sweets and odd things set out for sale. Then they were on the highroad and she saw hedges and trees. After that there seemed nothing different for a long time—or at least it seemed a long time to her.

At last the horses began to go more slowly, as if they were climbing up-hill, and presently there seemed to be no more hedges and no more trees. She could see nothing, in fact, but a dense darkness on either side. She leaned forward and pressed her face against the window just as the carriage gave a big jolt.

“Eh! We’re on the moor now sure enough,” said Mrs. Medlock.

The carriage lamps shed a yellow light on a rough-looking road which seemed to be cut through bushes and low growing things which ended in the great expanse of dark apparently spread out before and around them. A wind was rising and making a singular, wild, low, rushing sound.

“It’s—it’s not the sea, is it?” said Mary, looking round at her companion.

“No, not it,” answered Mrs. Medlock. “Nor it isn’t fields nor mountains, it’s just miles and miles and miles of wild land that nothing grows on but heather and gorse and broom, and nothing lives on but wild ponies and sheep.”

“I feel as if it might be the sea, if there were [Pg 27]water on it,” said Mary. “It sounds like the sea just now.”

“That’s the wind blowing through the bushes,” Mrs. Medlock said. “It’s a wild, dreary enough place to my mind, though there’s plenty that likes it—particularly when the heather’s in bloom.”

“I don’t like it,” she said to herself. “I don’t like it,” and she pinched her thin lips more tightly together.

The horses were climbing up a hilly piece of road when she first caught sight of a light. Mrs. Medlock saw it as soon as she did and drew a long sigh of relief.

“Eh, I am glad to see that bit o’ light twinkling,” she exclaimed. “It’s the light in the lodge window. We shall get a good cup of tea after a bit, at all events.”

It was “after a bit,” as she said, for when the [Pg 28]carriage passed through the park gates there was still two miles of avenue to drive through and the trees (which nearly met overhead) made it seem as if they were driving through a long dark vault.

They drove out of the vault into a clear space and stopped before an immensely long but low-built house which seemed to ramble round a stone court. At first Mary thought that there were no lights at all in the windows, but as she got out of the carriage she saw that one room in a corner up-stairs showed a dull glow.

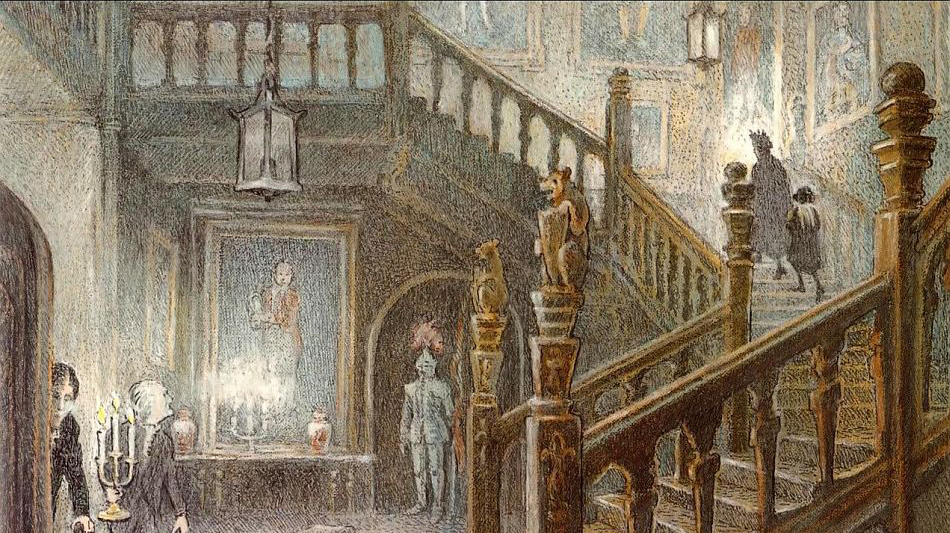

The entrance door was a huge one made of massive, curiously shaped panels of oak studded with big iron nails and bound with great iron bars. It opened into an enormous hall, which was so dimly lighted that the faces in the portraits on the walls and the figures in the suits of armor made Mary feel that she did not want to look at them. As she stood on the stone floor she looked a very small, odd little black figure, and she felt as small and lost and odd as she looked.

A neat, thin old man stood near the manservant who opened the door for them.

“You are to take her to her room,” he said in a husky voice. “He doesn’t want to see her. He’s going to London in the morning.”

“Very well, Mr. Pitcher,” Mrs. Medlock an[Pg 29]swered. “So long as I know what’s expected of me, I can manage.”

“What’s expected of you, Mrs. Medlock,” Mr. Pitcher said, “is that you make sure that he’s not disturbed and that he doesn’t see what he doesn’t want to see.”

And then Mary Lennox was led up a broad staircase and down a long corridor and up a short flight of steps and through another corridor and another, until a door opened in a wall and she found herself in a room with a fire in it and a supper on a table.

Mrs. Medlock said unceremoniously:

“Well, here you are! This room and the next are where you’ll live—and you must keep to them. Don’t you forget that!”

It was in this way Mistress Mary arrived at Misselthwaite Manor and she had perhaps never felt quite so contrary in all her life. Burnett