I TALK LIKE A RIVER

Written by Jordan Scott

Illustrated by Sydney Smith

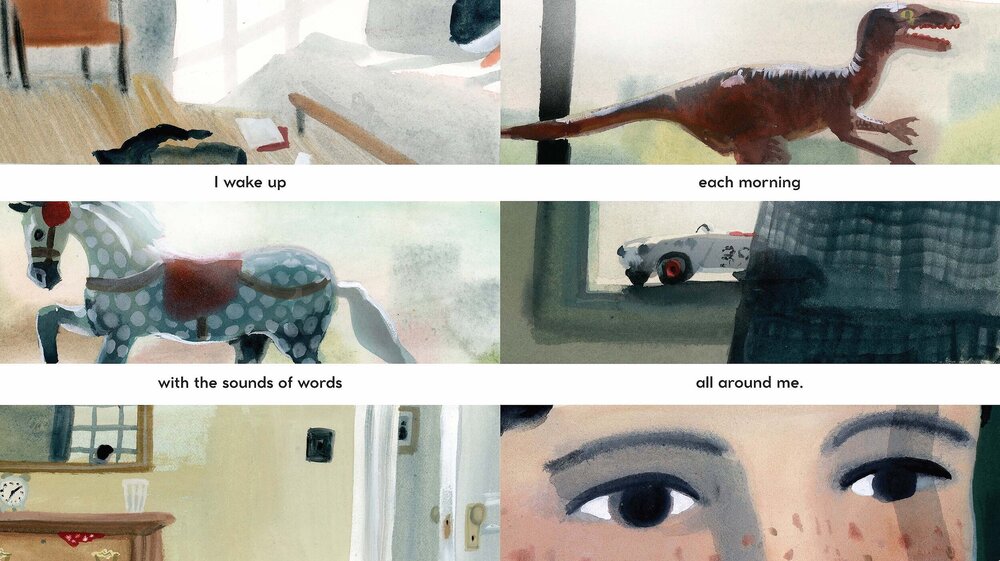

“I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me.

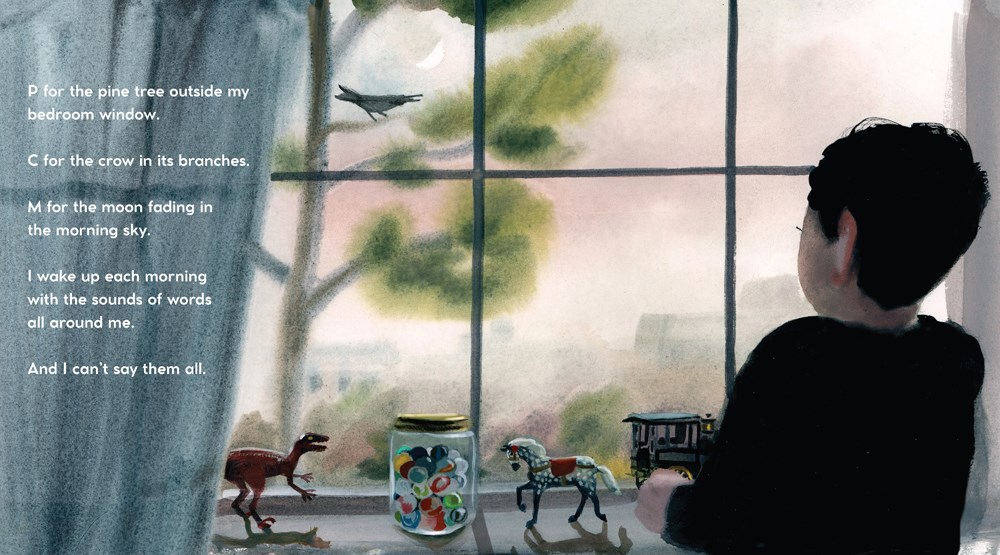

P for the pine tree outside my bedroom window.

C for the crow in its branches,

M for the moon fading in the morning sky.

I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me,

And I can’t say them all.

“The P in pine tree grows roots inside my mouth and tangles my tongue.

“The C is a crow that sticks in the back of my throat.

“The M in moon dusts my lips with magic that makes me only mumble.”

“I wake up in the morning with these word-sounds stuck in my mouth.

“I stay quiet as a stone.

“I eat my oatmeal without a peep.

“I get ready for the day without a word.”

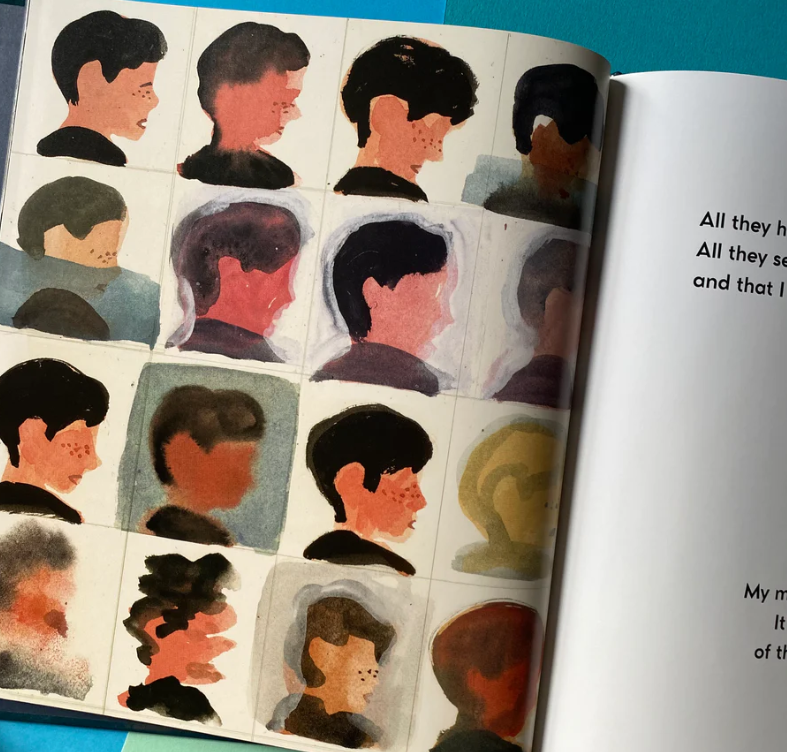

“At school, I hide in the back of class.

“I hope I don’t have to talk.

“When my teacher asks me a question,

all my classmates turn and look.”

“They don’t see a pine tree sticking out from my lips instead of a tongue.

“They don’t hear a crow Caw! Caw! from inside my throat.

“They don’t hide their eyes from the moonlight that shines from my open mouth.”

“All they hear is how I don’t talk like them.

“All they see is how strange my face looks and that I can’t hide how scared I am.

“My mouth isn’t working.

“It’s full with words of the morning.” . . .

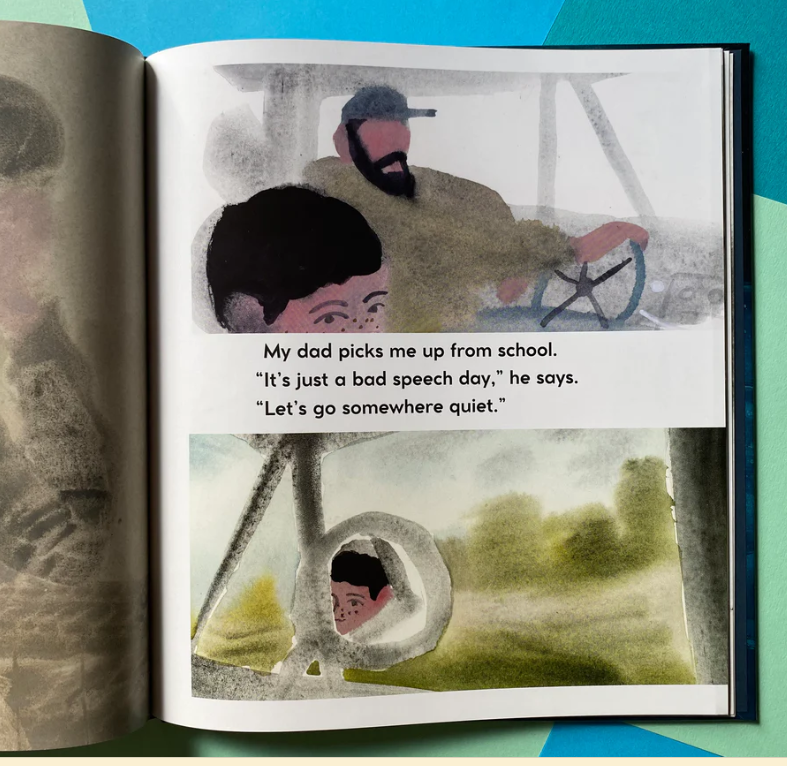

My dad picks me up from school.

“It’s just a bad speech day,” he says.

“Let’s go somewhere quiet.”

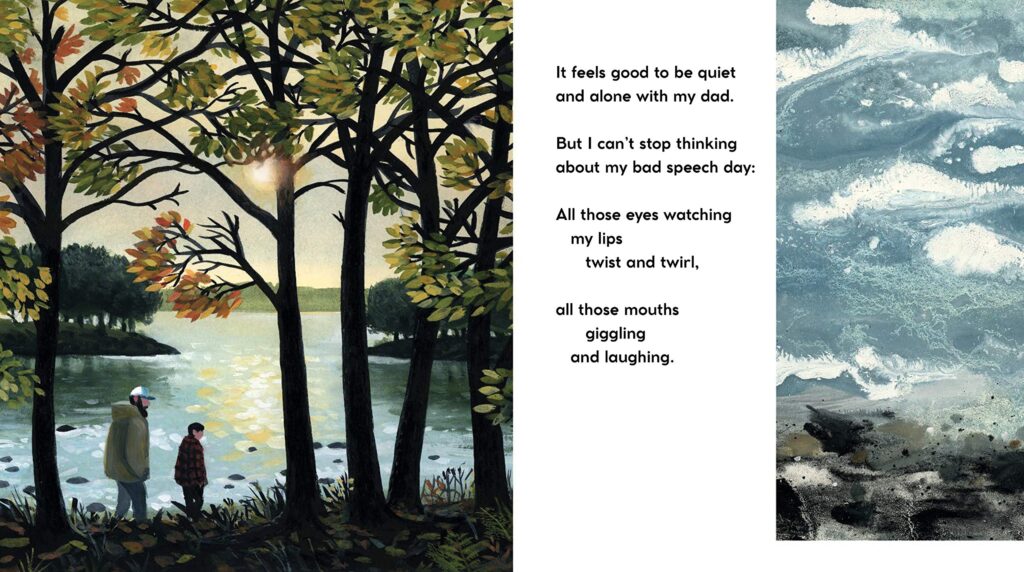

“My dad takes me to the river.

“We walk along the shore looking for colorful rocks and water bugs.”

“It feels good to be quiet and alone with my dad.

“But I can’t stop thinking about my bad speech day:

“All those eyes watching my lips twist and twirl,

“all those mouths giggling and laughing.”

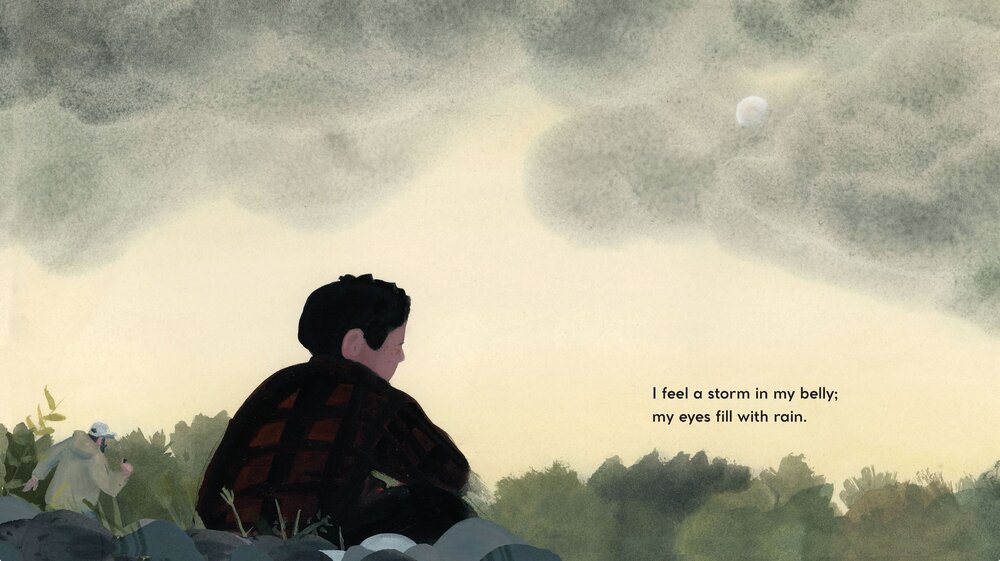

“I feel a storm in my belly;

“my eyes fill with rain.”

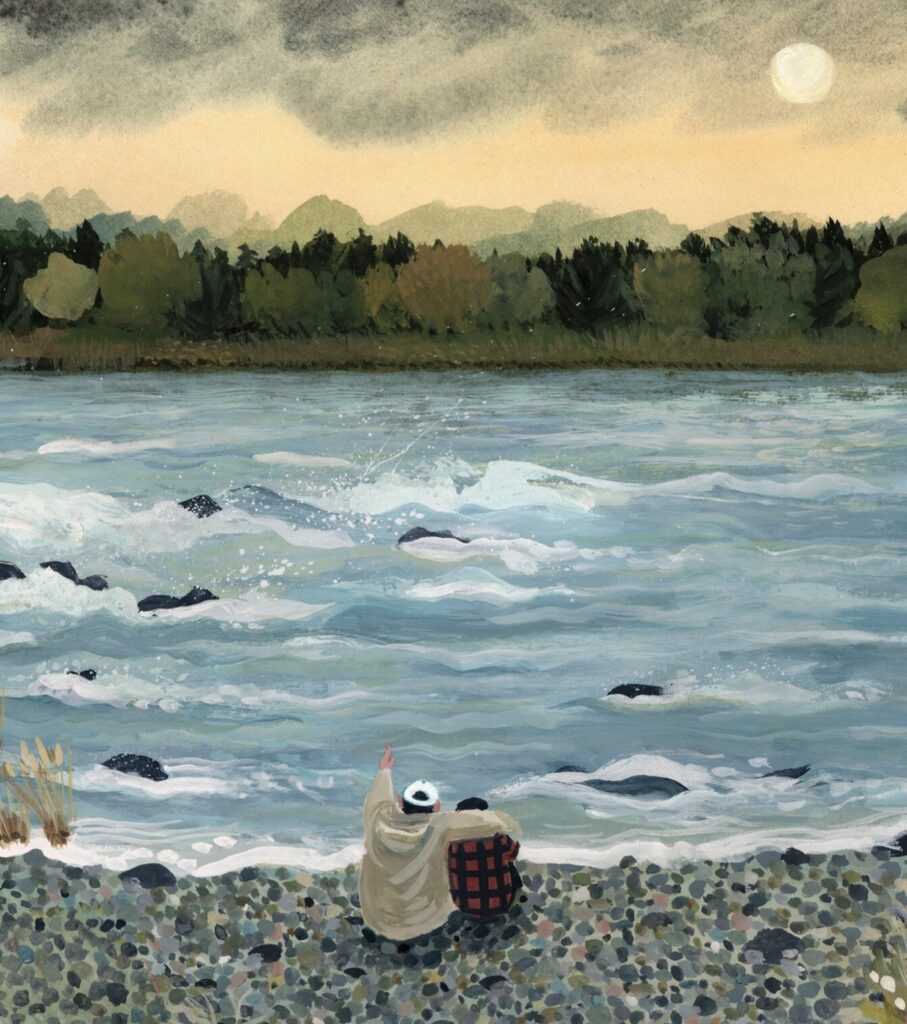

“My dad sees I am sad and pulls me

“close; he points to the river and says:

“See how that water moves?

“That’s how you speak.

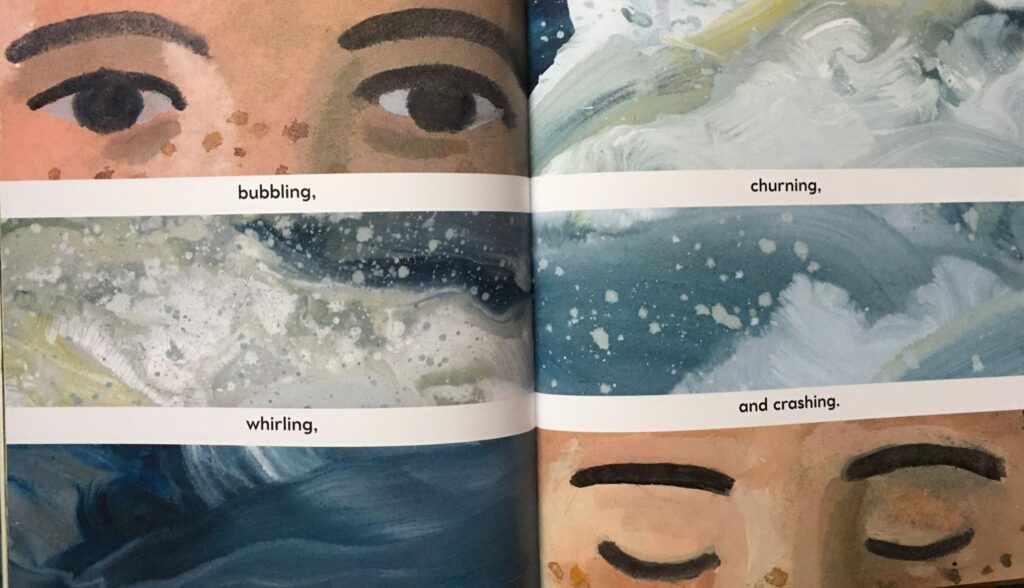

“I look at the water,

bubbling, churning, whirling, and crashing.

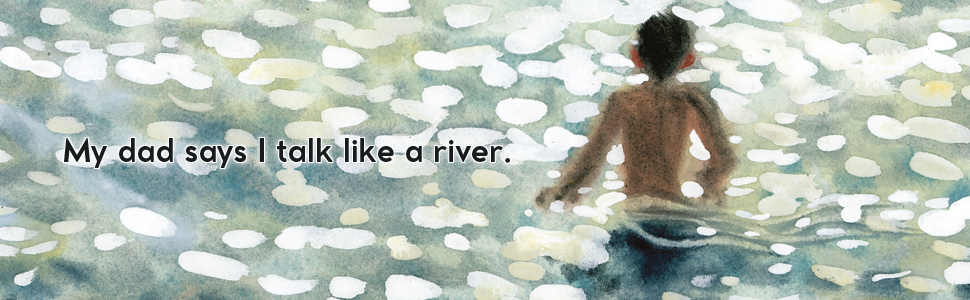

My dad says I talk like a river.

“This is what I like to remember,

“to help myself from crying

“I talk like a river….”

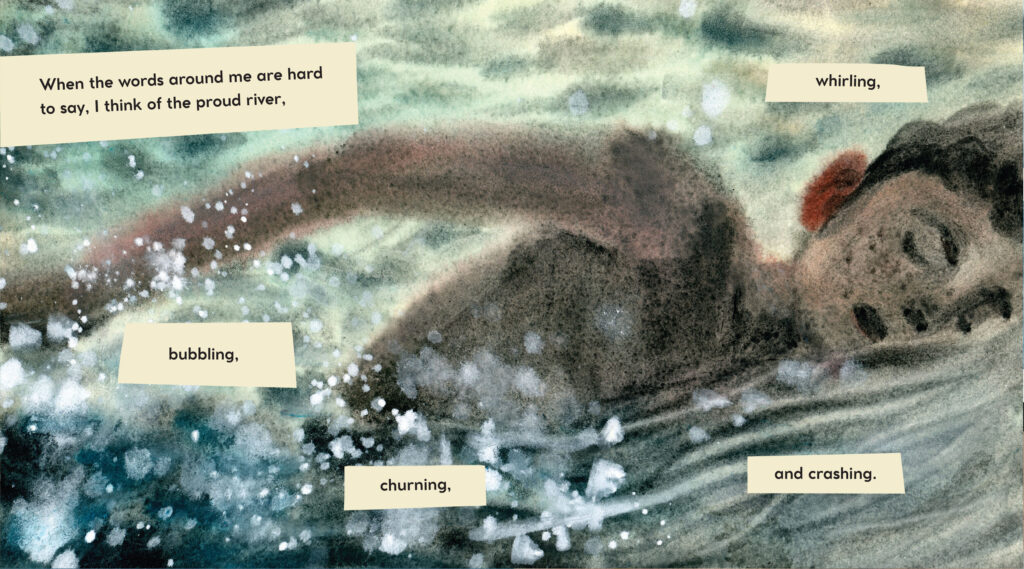

“When the words around me are hard to say, I think of the proud river, whirling,

“bubbling, churning, and crashing.”

“And I also think of the calm river beyond the rapids

“where the water is smooth and glistening.

“This is how my mouth moves.

“This is how I speak,

“Even the river stutters.

“Like I do.

“I wake up in the morning

with the sounds of words all around me.”

“I go to school and tell the class about

my favorite place in the world.

I talk about the river.” – Jordan Scott

________________________________________-

The following is a review of the picture book “I Talk Like A River:”

The New York Times

Nov. 4, 2020

“According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, around three million Americans stutter, and 5 percent to 10 percent of children will develop a stutter in their lifetime. As a child, I did, and still what I want to say sometimes feels as if it’s trapped in a bubble I can’t pop. My tongue loops around the stuck word or phrase, attempts alternate routes. I stare at the ceiling, begging patience with my eyes. A stutter, like other differences, can be frightening and painful because it threatens to isolate the stutterer. To a child, for whom social connection is paramount, this can be terrifying.

In “I Talk Like a River,” the Canadian poet Jordan Scott recalls his own childhood struggle with stuttering. His episodic narrative, told in a few straightforward sentences per page, accompanied by gorgeous illustrations by Sydney Smith, is an empathetic conversation-starter for families seeking help for a young — or not so young — person who stutters. Scott looks 8 or 9 in Smith’s renderings; freckled, with an intense, inward-looking gaze.

In the first pages, he stares out a window, contemplating his anxious relationship with words: “I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me./P for the pine tree outside my bedroom window./C for the crow in its branches.” But this is no uplifting abecedary. The story follows Scott from shame and fear to a state not of “fluency,” which implies a cure for stuttering, but, as he says in his short afterword, of self-acceptance and integration.

Smith has found a brilliant visual solution to show how stuttering creates a forced kind of, well, social distance. Working in generously applied water-based paints, he depicts people, rooms and nature with appealing warmth and precision, while also using the paint’s capacity to spread, bleed, run and dissolve to figure the ways speech will and won’t flow, and how the threat of being cut off can actually distort what the sufferer sees.

The most moving art accompanies Scott’s admission that “when my teacher asks me a question, all my classmates turn and look.” One illustration shows a soft, gummy vision of the classroom from the last row: the backs of the students’ heads, the brush strokes of their hair, the patterns on their sweaters. This all shifts in a second picture, which is blurred, almost dirty, the students’ indistinct faces turned menacingly toward the viewer, who sits in Scott’s place and seems to be retreating into himself, the light in the room fading.

“The story breathes a sigh of relief when the boy’s father takes him to a nearby river, a metaphor and even a role model for how turbulence and eddying are all part of the natural flow. A particularly powerful gatefold showing Scott’s troubled face across two pages opens out into a wide painting of him wading into the sun-speckled river, just as he is wading deliberately into the uneasy territory of his stutter.” Teicher, Craig Morgan. The New York Times.