“The Aegean world is a very beautiful one. The Islands rise out of the sea like jewels sparkling in the sunshine. It is a world associated with spring, of “fresh new grass and dewey lotus, and crocus and hyacinth,”[1] a land where the gods were born, one rich in legend and myth and fairy tale, and, most wonderful of all, a world where fairy tales have come true.

[1] The Book of the Ancient World.

“In 1876 a telegram from an archaeologist flashed through the world, saying he had found the tomb of wide-ruling Agamemnon, King of Men and Tamer of Horses; and later on, in Crete, traces were {7}found of the Labyrinth where Theseus killed the Minotaur. The spade of the archaeologist brought these things into the light, and a world which had hitherto seemed dim and shadowy and unreal suddenly came out into the sunshine.

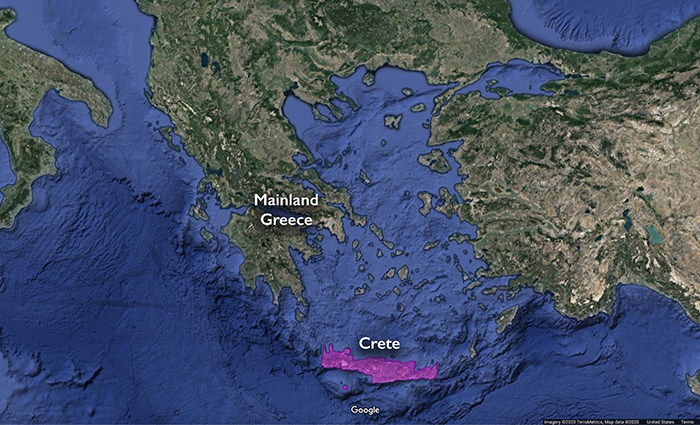

“There is a land called Crete in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair land and a rich, begirt with water, and therein are many men innumerable and ninety cities.[2]

[2] Odyssey, XIX.

“Legend tells us that it was in this land that Zeus was born, and that a nymph fed him in a cave with honey and goat’s milk. Here, too, in the same cave was he wedded and from this marriage came Minos, the legendary Hero-King of Crete. The name Minos is probably a title, like Pharaoh or Caesar…

“The first traces of history in Crete take us back to about 2500 B.C. but it was not till about a thousand years later that Crete was at the height of her prosperity and enjoying her Golden Age. Life in Crete at this time must have been happy. The Cretans built their cities without towers or fortifications; they were a mighty sea power, but they lived more {10}for peace and work than for military or naval adventures, and having attained the overlordship of the Aegean, they devoted themselves to trade, industries and art.

“The Cretans learnt a great deal from Egypt, but they never became dependent upon her as did the Phoenicians, that other seafaring race in the Mediterranean. They dwelt secure in their island kingdom, taking what they wanted from the civilization they saw in the Nile Valley; but instead of copying this, they developed and transformed it in accordance with their own spirit and independence.

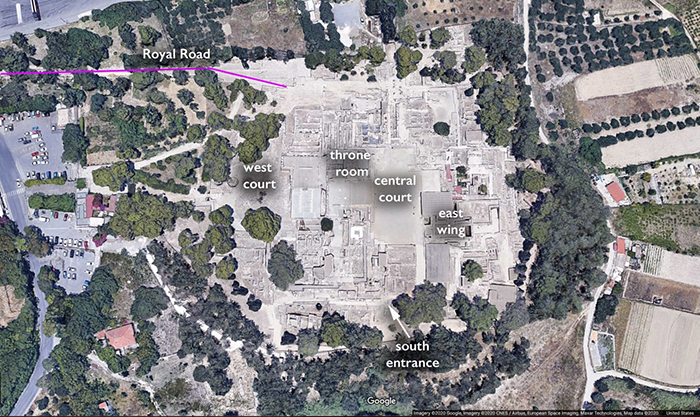

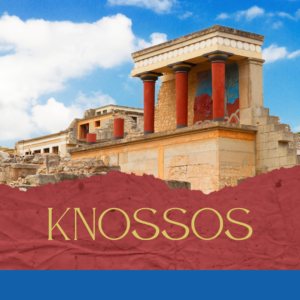

“The chief city in Crete was Knossos, and the great palace there is almost like a town. It is built round a large central court, out of which open chambers, halls and corridors. This court was evidently the centre of the life of the palace. The west wing was probably devoted to business and it was here that strangers were received. In the audience chamber was found a simple and austere seat, yet one which seizes upon the imagination, for it was said to be the seat of Minos, and is the oldest known royal throne in the world.

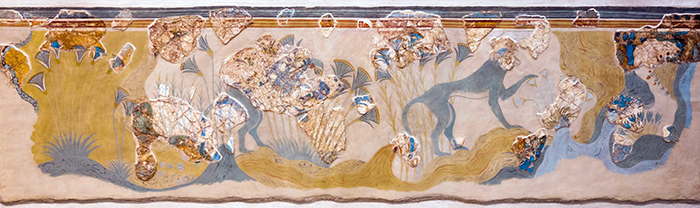

“In the east wing lived the artisans who were employed in decorating and working on the building, for everything required in the palace was made on the spot. The walls of all the rooms were finished with smooth plaster and then painted; originally that the paint might serve as a protection, but later because the beauty-loving Cretans liked their walls to be covered with what must have been a joy to look at, and which reminded them at every turn of {11}the world of nature in which they took such a keen delight. The frescoes are now faded, but traces of river-scenes and water, of reeds and rushes and of waving grasses, of lilies and the crocus, of birds with brilliant plumage, of flying fish and the foaming sea can still be distinguished.

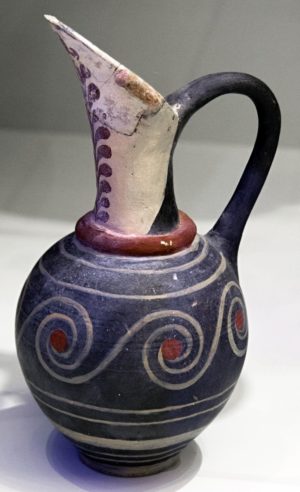

“The furniture has all perished, but many household utensils have been found which show that life was by no means primitive, and the palaces were evidently built and lived in by people who understood comfort. In some ways they are quite modern, especially in the excellent drainage system they possessed. These Cretan palaces were warmer and more full of life than those in Assyria, and they were dwelt in by a people who were young and vigorous and artistic, and who understood the joy of the artist in creating beauty.

“Near the palace was the so-called theatre. The steps are so shallow that they could not have made comfortable seats, and the space for performances was too small to have been used for bull-fights, which were the chief public entertainments. The place was probably used for dancing, and it may have been that very dancing ground wrought for Ariadne.[6]”

Mills, Dorothy. The Book of the Ancient Greeks. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1925.

Image Credit Khan Academy

“There aren’t many places in the world like Knossos. Situated 6km south of the sea, on the north central coast of Crete, several things make this archaeological site important: its great antiquity (it is 9,000 years old), many different cultural layers (Neolithic through Byzantine), its size (nearly 10 square Km) and its great popularity (the second most visited archaeological site in Greece after the Acropolis at Athens).

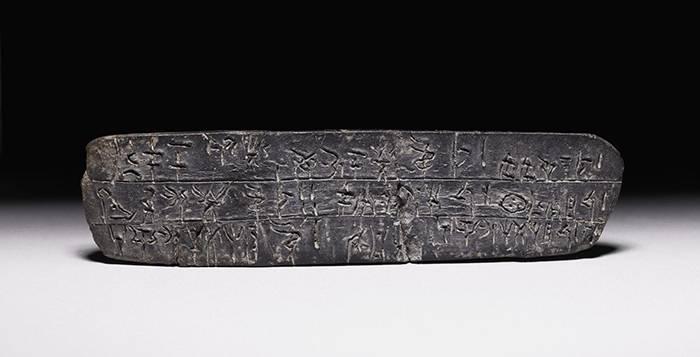

“Aside from these, however, Knossos is also exceptional because of its role in the writing of history. It is the type site for all of Minoan archaeology, was one of the first large-scale scientific excavations in Europe, and contains some of the most contentious restorations in the ancient Mediterranean. Because of all this, Knossos is a critical part of multiple discourses in the history and historiography of the ancient world. We can’t stop talking about Knossos.

A palace?

Early Knossos

“The site of Knossos was first inhabited around 7000 B.C.E. and was one of the earliest Neolithic sites in the Mediterranean, settled at a time when pottery had yet to be invented. It continued to be a well-populated site for successive Neolithic eras, one literally building upon another, eventually creating one of the only tell sites of the Aegean, nearly 100 meters above sea level. Unfortunately, not a lot is known about Neolithic Knossos as the Bronze Age inhabitants entirely covered over its remains with their own structures. However, limited excavations show that it was one of the oldest farming villages in Europe which had connections to even earlier Mesolithic inhabitants elsewhere on the island.

Before the palace

Protopalatial or Old Palace Knossos

Neopalatial or New Palace Knossos

Postpalatial or Final Palatial Knossos

Cretan and mainland cultures

“A lot about Postpalatial Knossos has a distinct Mycenaean flavor and this fact has led many archaeologists to conclude that the destructions at the beginning of the period were actually the Mycenaeans invading the island. However, many Minoan elements remain in Postpalatial culture, and obvious signs of warfare which would have resulted from a large-scale invasion have yet to be found. Therefore, we now like to think of the Postpalatial period at Knossos as one of a hybrid, between Cretan and Mainland cultures, likely created by a local elite who wished to maintain status in both spheres. As to who exactly these local elite were, we have some information. Those buried in warrior graves in the Postpalatial cemeteries around Knossos were born in the region, as recent analysis of skeletal materials has shown. The new Knossian elite did not come from the Mycenaean mainland.

Knossos collapses . . . and rises again

Knossos wasn’t down for long. Rapidly after the late Bronze Age collapse a large Early Iron Age settlement emerged north of the palace and was clearly cosmopolitan as it was the only site of the period in Greece with imports ranging from the Middle East to Sardinia. This area eventually develops into a Classical Greek polis (city-state) and in the 1st century B.C.E. suffers Roman conquest. Beautiful mosaics survive from a 2nd century C.E. Roman home, the Villa Dionysos, evidence of the thriving Roman city at the site. A large Christian church is built at the north edge of the site in the 6th century, witness to the Byzantine history of Knossos.

Why Are Archaeological Excavations Important?

“The archaeological site of Knossos (on the island of Crete) —traditionally called a palace—is the second most popular tourist attraction in all of Greece (after the Acropolis in Athens), hosting hundreds of thousands of tourists a year. But its primary attraction is not so much the authentic Bronze Age remains (which are more than three thousand years old) but rather the extensive early 20th century restorations installed by the site’s excavator, Sir Arthur Evans, in the early twentieth century.

“Archaeological restorations offer important information about the history of a site and Knossos doesn’t disappoint—one can see the earliest throne room in Europe, walk through the monumental Northern entrance to the palace, marvel at colorful wall paintings and enjoy the elegance of a queen’s apartments. All these spaces, however, are the result of extensive, contentious and, in some cases, damaging restoration. Knossos asks us to consider how we can preserve an archaeological site, while at the same time providing a valuable, educational experience for visitors that nonetheless remains true to the remains.

Considering Evans’ reconstructions

-

If Evans hadn’t worked to preserve and restore so much of Knossos beginning in 1901, it would have undoubtedly been largely lost.

-

The restoration of the site undertaken by Evans, with its elegantly painted Throne Room (below) makes very real our historical understanding, originally revealed by Homer, of the power and prestige of the kings of Crete.

-

The beautiful, although sometimes inaccurate, restorations of architecture and wall paintings by Evans evoke the elegance and skill of Minoan architects and painters.

“Evans’s restoration of the Throne Room (and much else at the site) privileges the Late Bronze Age period of its history. The typical visitor likely won’t grasp that the Throne Room dates to the latest phase of Knossos—the end of the 2nd millennium B.C.E., though the site was occupied nearly continuously from the Neolithic to the Roman era (from the 8th millennium B.C.E. to at least the 5th century C.E.).

Restoration at Knossos

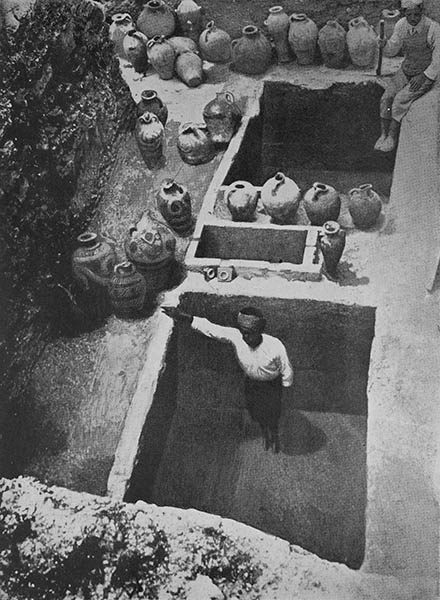

“Aside from some gaps (for instance, during the First World War) Evans excavated at the site of Knossos each year from 1900 to 1930. Restoration of the architectural finds began almost immediately and can be divided into three phases, each characterized by the architect Evans hired to do the work. These three men, Theodore Fyfe, Christian Doll, and Piet De Jong, each had very different restoration philosophies.

Phase 1: Theodore Fyfe

“From 1901 to 1904, a young architect by the name of Theodore Fyfe was charged with the restorations at Knossos. It is likely that Evans hired him because the winter of 1900/01 had damaged the newly exposed Throne Room—the most important space excavated during that first season at the site.

“Fyfe’s work at Knossos can be characterized by two things. First of all, he was devoted to the concept of minimal intervention. Second, when intervention was necessary, he made great efforts to use materials authentic to the Bronze Age structure (wood, limestone, rubble masonry) and even to use Bronze Age construction techniques, which he was able to glean from his onsite work. Clearly, Fyfe was highly concerned about the truthfulness of his interventions and reconstructions; the only exception to this was his construction of modern-style pitched roofs to protect the Throne Room and the Shrine of the Double Axes.

Phase 2: Christian Doll

“The second phase of restoration work at Knossos dates from 1905 to 1910, and was directed by Christian Doll. The first conservation work to which Doll had to attend to in 1905 was that of Fyfe’s. Essentially, Fyfe’s zeal to use authentic materials resulted in failure: he neglected in many cases to treat timbers before their use and he tended to use softwoods rather than hardwoods (all of which lead to rot). Also, rain was a destructive force in the winters, especially when it ran through newly exposed parts of the site. Doll’s first and most important project was to stabilize and reconstruct the Grand Staircase to its original four story height. This was an extremely difficult job as the exact nature of the ancient design eluded both him and Fyfe, so a certain amount of improvisation was needed. And, because the weight of the structure was so great, Doll used iron girders (imported from England at great expense) covered in cement to make them look like ancient wooden beams.

“Doll’s approach to conservation was still anchored in preserving the excavated remains. However, Doll was no fan of the authentic materials used by Fyfe, as he saw how they had failed to preserve the many areas where they had been employed. Instead, Doll constructed structural systems based on techniques used in London at the time. Moreover, he employed contemporary architectural materials, such as the iron girders mentioned above, as well as concrete (the first use of this material at Knossos).

Piet de Jong, reconstruction of the “Dolphin Fresco,” Queen’s Megaron, Knossos (public domain)

An enticing mystery

at Knossos on Crete, is one of the most frequently reproduced sculptures from antiquity. Whether or not this is true, it is certainly the case that she is a powerful and evocative image. What she meant to the Minoans who made her, however, is not very well understood.

The Snake Goddess prior to restoration by Evans, from Angelo Mosso, The Palaces of Crete and Their Builders (London: Unwin, 1907), p. 137 (University of Toronto Libraries)

The hat and the cat

“In her restored state, the Snake Goddess is 29.5 cm (about 11.5 inches) high, a youthful woman wearing a full skirt made of seven flounced layers of multicolored cloth. This is likely not a representation of striped cloth, but rather flounces made from multiple colorful bands of cloth, the weaving of which was a Minoan specialty. Over the skirt she wears a front and back apron decorated with a geometric diamond design. The top of the skirt and apron has a wide, vertically-striped band that wraps tightly around the figure’s waist. On top, she wears a short-sleeved, striped shirt tied with an elaborate knot at the waist, with a low-cut front that exposes her large, bare breasts. The Snake Goddess’s head, restored by Bagge and Evans, stares straight forward, topped by the spherical object that Bagge and Evans believed would make a good crown, and, finally, a small sitting cat. Her long black hair hangs down her back and curls down around her breasts.

Really a goddess?

German, Senta. “Conservation Vs. Restoration: The Palace at Knossos (Crete).” Khan Academy, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/aegean-art1/minoan/a/conservation-vs-restoration-the-palace-at-knossos-crete. Accessed 5 Sept. 2022.

German, Senta. “Knossos.” Khan Academy, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/aegean-art1/minoan/a/knossos. Accessed 5 Sept. 2022.