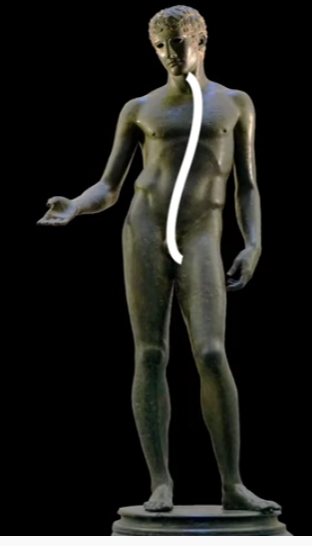

Before the era of Ancient Greece, artists and artisans depicted the human figure as a straight and rigid form. The Ancient Greeks discovered that the more natural, the more human way, to depict the figure is that presented in Contrapposto.

In simplistic terms, a figure standing in Contrapposto will place his weight on only one foot. In doing so, the body will shift. One shoulder will drop below the other, and the body’s spine will comply with the lines of an “S.”

Bronze statuette of a youth dancing late 4th century B.C. Greek

“This beautiful bronze captures a moment when the full achievement of Classical art began to be used for the representation of a single, transitory state. The youth is nude except for a crown of myrtle, an attribute of followers of the god Dionysos. His pose no longer dictates one primary view, for his torso and legs assume a true contrapposto, and his downward glance reinforced by the direction of the arms makes a rather tight spiral of the whole composition. There is a perfect congruence among all parts of the figure, but the shifts in direction evident from every angle maintain an effect of instability and impermanence.” The Met: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/255407

Oedipus and the Sphinx

1864

Gustave Moreau French at the Met: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437153

“The legendary Greek prince Oedipus confronts the malevolent Sphinx, who torments travelers with a riddle: What creature walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three legs in the evening? Remains of victims who answered incorrectly litter the foreground. (The solution is the human, who crawls as a baby, strides upright in maturity, and uses a cane in old age.) Moreau made his mark with this painting at the Paris Salon of 1864. Despite the growing prominence of depictions of everyday life, he portrayed stories from the Bible, mythology, and his imagination. His otherworldly imagery inspired many younger artists and writers, including Odilon Redon and Oscar Wilde.” The Met

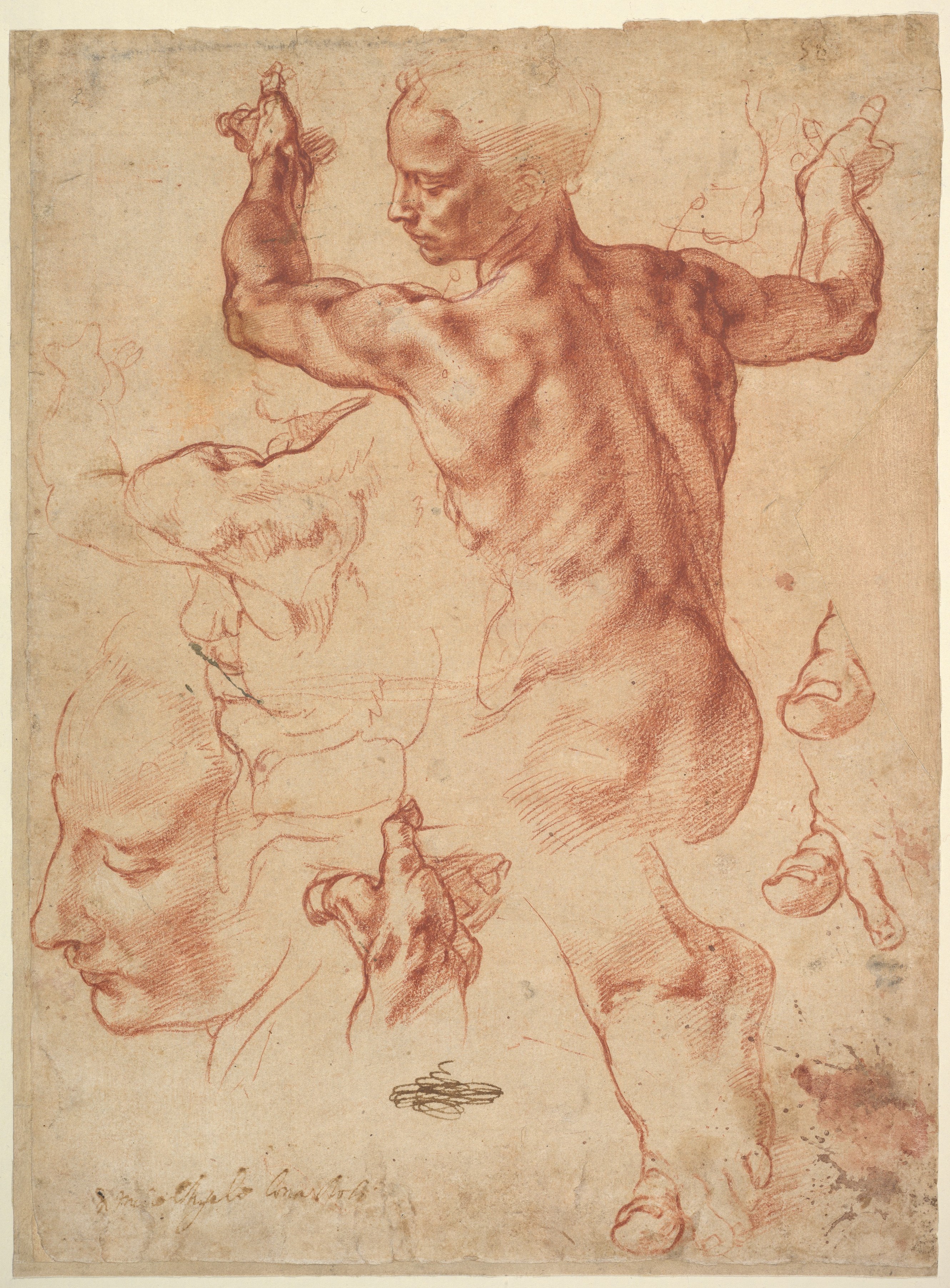

Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto); Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso)

ca. 1510–11

Michelangelo Buonarroti at the Met: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/337497