Plants of the Christian Church.

“After Rome Pagan became Rome Christian, the priests of the Church of Christ recognised the importance of utilising the connexion which existed between plants and the old pagan worship, and bringing the floral world into active co-operation with the Christian Church by the institution of a floral symbolism which should be associated not only with the names of saints, but also with the Festivals of the Church.

Ancient Pagan Holidays Celebrated Today–Some of Them Are Celebrated as Christian“But it was more especially upon the Virgin Mary that the early Church bestowed their floral symbolism. Mr. Hepworth Dixon, writing of those quiet days of the Virgin’s life, passed purely and tenderly among the flowers of Nazareth, says—“Hearing that the best years of her youth and womanhood were spent, before she yet knew grief, on this sunny hill and side slope, her feet being for ever among the Daisies, Poppies, and Anemones, which grow everywhere about, we have made her the patroness of all our flowers. The Virgin is our Rose of Sharon—our Lily of the Valley. The poetry no less than the piety of Europe has inscribed to her the whole bloom and colouring of the fields and hedges.” “The choicest flowers were wrested from the classic Juno, Venus, and Diana, and from the Scandinavian Bertha and Freyja, and bestowed upon the Madonna, whilst floral offerings of every sort were laid upon her shrines. “Her husband, Joseph, has allotted to him a white Campanula, which in Bologna is known as the little Staff of St. Joseph. In Tuscany the name of St. Joseph’s staff is given to the Oleander: a legend recounts that the good Joseph possessed originally only an ordinary staff, but that when the angel announced to him that he was destined to be the husband of the Virgin Mary, he became so radiant with joy, that his very staff flowered in his hand. “Before our Saviour’s birth, the Virgin Mary, strongly desiring to refresh herself with some luscious cherries that were hanging in clusters upon the branch of a tree, asked Joseph to gather some for her. He hesitated, and mockingly said—“Let the father of thy child present them to you.” Instantly the branch of the Cherry-tree inclined itself to the Virgin’s hand, and she plucked from it the refreshing fruit. On this account the Cherry has always been dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The Strawberry, also, is specially set apart to the Virgin’s use; and in the Isle of Harris a species of Beans, called Molluka Beans, are called, after her, the Virgin Mary’s Nuts. “At Bethlehem, the manger in which the Infant Jesus was laid after His birth was filled with Our Lady’s Bedstraw (Galium verum). Some few drops of the Virgin’s milk fell upon a Thistle, which from that time has had its leaves spotted with white, and is known as Our Lady’s Thistle (Carduus Marianus). In Germany the Polypodium vulgare, which grows in clefts of rocks, is believed to have sprung from the milk of the Virgin (in ancient times from Freyja’s milk). The Pulmonaria is also known as Unser Frauen Milch (Our Lady’s Milk). “When, after the birth of Jesus, His parents fled into Egypt, traditions record that in order that the Virgin might conceal herself and the infant Saviour from the assassins sent out by Herod, various trees opened, or stretched their branches and enlarged their leaves. As the Juniper is dedicated to the Virgin, the Italians consider that it was a tree of that species which thus saved the mother and child, and the Juniper is supposed to possess the power of driving away evil spirits and of destroying magical spells. The Palm, the Willow, and the Rosemary have severally been named as having afforded their shelter to the fugitives. On the other hand, the Lupine, according to a tradition still current among the Bolognese, received the maledictions of the Virgin Mary because, during the flight, certain plants of this species, by the noise they made, drew the attention of the soldiers of Herod to the spot where the harassed travellers had halted. “During the flight into Egypt a legend relates that certain precious bushes sprang up by the fountain where the Virgin washed the swaddling clothes of her Divine babe. These bushes were produced by the drops of water which fell from the clothes, and from which germinated a number of little plants, each yielding precious balm. Wherever the Holy Family rested in their flight sprang up the Rosa Hierosolymitana—the Rosa Mariæ, or Rose of the Virgin. Near the city of On there was shown for many centuries the sacred Fig-tree under which the Holy Family rested. They also, according to Bavarian tradition, rested under a Hazel.

Plants of the Virgin Mary.

“In Tuscany there grows on walls a rootless little pellitory (Parietaria), with tiny pale-pink flowers and small leaves. They gather it on the morning of the Feast of the Ascension, and suspend it on the walls of bed-rooms till the day of the Nativity of the Virgin (8th September), from which it derives its name—the Herb of the Madonna. It generally opens its flowers after it has been gathered, retaining sufficient sap to make it do so. This opening of a cut flower is regarded by the peasantry as a token of the special blessing of the Virgin. Should the flower not open, it is taken as an omen of the Divine displeasure. In the province of Bellune, in Italy, the Matricaria Parthenium is called the Herb of the Blessed Mary: this flower was formerly consecrated to Minerva. “In Denmark, Norway, and Iceland, they give the name of Mariengras (Herb of Mary) to different Ferns, and in those countries Mary often replaces the goddess Freyja, the Venus of the North, in the names of flowers. No doubt the monks of old delighted in bestowing upon the Virgin Mary the floral attributes of Venus, Freyja, Isis, and other goddesses of the heathen; but, nevertheless, it is not long since that a Catholic writer complained that at the Reformation “the very names of plants were changed in order to divert men’s minds from the least recollection of ancient Christian piety;” and a Protestant writer of the last century, bewailing the ruthless action of the Puritans in giving to the “Queen of Beauty” flowers named after the “Queen of Heaven,” says: “Botany, which in ancient times was full of the Blessed Virgin Mary, … is now as full of the heathen Venus.” “Amongst the titles of honour given to the Virgin in the ‘Ballad of Commendation of Our Lady,’ in the old editions of Chaucer, we find: “Benigne braunchlet of the Pine tree.”” “In England “Lady” in the names of plants generally has allusion to Our Lady, Notre Dame, the Virgin Mary. Our Lady’s Mantle (Alchemilla vulgaris) is the Máríu Stakkr of Iceland, which insures repose when placed beneath the pillow. Scandix Pecten was Our Lady’s Comb, but in Puritan times was changed into Venus’ Comb. The Cardamine pratensis is Our Lady’s Smock; Neottia spiralis, Our Lady’s Tresses; Armeria vulgaris, Our Lady’s Cushion; Anthyllis vulneraria, Our Lady’s Fingers; Campanula hybrida, Our Lady’s Looking-glass; Cypripedium Calceolus, Our Lady’s Slipper; the Cowslip, Our Lady’s Bunch of Keys; Black Briony, Our Lady’s Seal (a name which has been transferred from Solomon’s Seal, of which the ‘Grete Herbal’ states, “It is al one herbe, Solomon’s Seale and Our Lady’s Seale”). Quaking Grass, Briza media, is Our Lady’s Hair; Maidenhair Fern, the Virgin’s Hair; Mary-golds (Calendula officinalis) and Mary-buds (Caltha palustris) are both named after the Virgin Mary. The Campanula and the Digitalis are in France the Gloves of Mary; the Nardus Celtica is by the Germans called Marienblumen; the White-flowered Wormwood is Unser Frauen Rauch (Smoke of Our Lady); Mentha spicata is in French, Menthe de Notre Dame—in German, Unser Frauen Müntz; the Costus hortensis, the Eupatorium, the Matricaria, the Gallitrichum sativum, the Tanacetum, the Persicaria, and a Parietaria are all, according to Bauhin, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The name of Our Lady’s Tears, or Larmes de Sainte Marie, has been given to the Lily of the Valley, as well as to the Lithospermon of Dioscorides, the Satyrium maculatum, and the Satyrium basilicum majus. The Narcissus Italicus is the Lily of Mary. The Toad Flax is in France Lin de Notre Dame, in Germany, Unser Frauen Flachs. The Dead-Nettle is Main de Sainte Marie. Besides the Alchemilla, the Leontopodium, the Drosera, and the Sanicula major are called on the Continent Our Lady’s Mantle. Woodroof, Thyme, Groundsel, and St. John’s Wort form the bed of Mary. “In Piedmont they give the name of the Herb of the Blessed Mary to a certain plant that the birds are reputed to carry to their young ones which have been stolen and imprisoned in cages, in order that it shall cause their death and thus deliver them from their slavery. “The Snowdrop is the Fair Maid of February, as being sacred to the Purification of the Virgin (February 2nd), when her image was removed from the altar and Snowdrops strewed in its place. “To the Madonna, in her capacity of Queen of Heaven, were dedicated the Almond, the White Iris, the White Lily, and the Narcissus, all appropriate to the Annunciation (March 25th). The Lily and White and Red Roses were assigned to the Visitation of Our Lady (July 2nd): these flowers are typical of the love and purity of the Virgin Mother. To the Feast of the Assumption (August 15th) is assigned the Virgin’s Bower (Clematis Flammula); to the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin (September 8th) the Amellus (Aster Amellus); and to the Conception (December 8th) the Arbor Vitæ. “St. Dominick instituted the “Devotion of the Rosary” of the Virgin Mary—a series of prayers, to mark the repetition of which a chaplet of beads is employed, which consists of fifteen large and one hundred and fifty small beads; the former representing the number of Pater Nosters, the latter the number of Ave Marias. As these beads were formerly made of Rose-leaves tightly pressed into round moulds, where real Roses were not strung together, this chaplet was called a Rosary, and was blessed by the Pope or some other holy person before being so used. Valeriana sativa is in France called Herbe de Marie Magdaleine, in Germany Marien Magdalenen Kraut; the Pomegranate is the Pommier de Marie Magdaleine and Marien Magdalenen Apfel.The Plants of Our Saviour.

“We have seen that at the birth of Christ, the infant Jesus was laid on a manger containing Galium verum, at Bethlehem, a place commemorated by the Ornithogalum umbellatum, or Star of Bethlehem, the flowers of which resemble the pictures of the star that indicated the birth of Jesus. Whilst lying in the manger, a spray of the rose-coloured Sainfoin, says a French legend, was found among the dried grass and herbs which served for His bed. Suddenly the Sainfoin began to expand its delicate blossoms, and to the astonishment of Mary, formed a wreath around the head of the holy babe. In commemoration of the infant Saviour having laid on a manger, it is customary, in some parts of Italy, to deck mangers at Christmas time with Moss, Sow-Thistle, Cypress, and prickly Holly: boughs of Juniper are also used for Christmas decorations, because tradition affirms that the Virgin and Child found safety amongst its branches when pursued by Herod’s mercenaries. The Juniper is also believed to have furnished the wood of the Cross on which Jesus was crucified. “At Christmas, according to an ancient pious tradition, all the plants rejoice. In commemoration of the birth of our Saviour, in countries nearer His birthplace than England, the Apple, Cherry, Carnation, Balm, Rose of Jericho, and Rose of Mariastem (in Alsatia), burst forth into blossom at Christmas, whilst in our own land the day is celebrated by the blossoming of the Glastonbury Thorn, sprung from St. Joseph’s staff, and the flowering of the Christmas Rose, or Christ’s Herb, known in France as la Rose de Noel, and in Germany as Christwurzel. “On Good Friday, in remembrance of the Passion of our Lord, all the trees, says the legend, shudder and tremble. The Swedes and Scotch have a tradition that Christ was scourged with a rod of the dwarf Birch, which was once a noble tree, but has ever since remained stunted and lowly. It is called Láng Fredags ris, or Good Friday rod. There is another legend extant, which states that the rod with which Christ was scourged was cut from a Willow, and that the trees of its species have drooped their branches to the earth in grief and shame from that time, and have, consequently, borne the name of Weeping Willows.The Crown of Thorns.

“Sir J. Maundevile, who visited the Holy Land in the fourteenth century, has recorded that he had many times seen the identical crown of Thorns worn by Jesus Christ, one half of which was at Constantinople and the other half at Paris, where it was religiously preserved in a vessel of crystal in the King’s Chapel. This crown Maundevile says was of “Jonkes of the see, that is to sey, Rushes of the see, that prykken als scharpely as Thornes;” he further adds that he had been presented with one of the precious thorns, which had fallen off into the vessel, and that it resembled a White Thorn. The old traveller gives the following circumstantial account of our Lord’s trial and condemnation, from which it would appear that Jesus was first crowned with White Thorn, then with Eglantine, and finally with Rushes of the sea. He writes:—“In that nyghte that He was taken, He was ylad into a gardyn; and there He was first examyned righte scharply; and there the Jewes scorned Him, and maden Him a croune of the braunches of Albespyne, that is White Thorn, that grew in the same gardyn, and setten it on His heved, so faste and so sore, that the blood ran doun be many places of His visage, and of His necke, and of His schuldres. And therefore hathe the White Thorn many vertues; for he that berethe a braunche on him thereoffe, no thondre, ne no maner of tempest may dere him; ne in the hows that it is inne may non evylle gost entre ne come unto the place that it is inne. And in that same gardyn Seynt Petre denyed oure Lord thryes. Aftreward was oure Lord lad forthe before the bischoppes and the maystres of the lawe, in to another gardyn of Anne; and there also He was examyned, repreved, and scorned, and crouned eft with a White Thorn, that men clepethe Barbarynes, that grew in that gardyn; and that hathe also manye vertues. And afterward He was lad into a gardyn of Cayphas, and there He was crouned with Eglentier. And aftre He was lad in to the chambre of Pylate, and there He was examynd and crouned. And the Jewes setten Hym in a chayere and cladde Hym in a mantelle; and there made thei the croune of Jonkes of the see; and there thei kneled to Hym, and skorned Hym, seyenge: ‘Heyl, King of the Jewes!’”

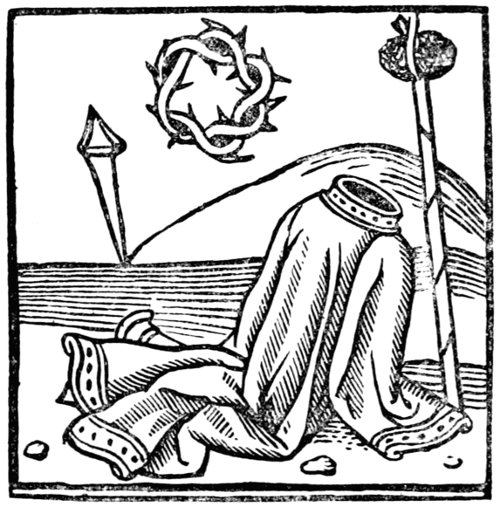

Relics of the Crucifixion. From Maundevile’s Travels.

“The illustration represents the Crown of Thorns, worn by our Saviour, his coat without seams, called tunica inconsutilis; the sponge; the reed by means of which the Jews gave our Lord vinegar and gall; and one of the nails wherewith He was fastened to the Cross. All these relics Maundevile tells us he saw at Constantinople. “Of what particular plant was composed the crown of Thorns which the Roman soldiers plaited and placed on the Saviour’s head, has long been a matter of dispute. Gerarde says it was the Paliurus aculeatus, a sharp-spined shrub, which he calls Christ’s Thorn; and the old herbalist quotes Bellonius, who had travelled in the Holy Land, and who stated that this shrubby Thorn was common in Judea, and that it was “The Thorne wherewith they crowned our Saviour Christ.” The melancholy distinction has, however, been variously conferred on the Buckthorns, Rhamnus Spina Christi and R. Paliurus; the Boxthorn, the Barberry, the Bramble, the Rose-briar, the Wild Hyssop, the Acanthus, or Brank-ursine, the Spartium villosum, the Holly (called in Germany, Christdorn), the Acacia, or Nabkha of the Arabians, a thorny plant, very suitable for the purpose, since its flexible twigs could be twisted into a chaplet, and its small but pointed thorns would cause terrible wounds; and, in France, the Hawthorn—the épine noble. The West Indian negroes state that Christ’s crown was composed of a branch of the Cashew-tree, and that in consequence one of the golden petals of its blossom became black and blood-stained. The Reed Mace (Typha latifolia) is generally represented as the reed placed, in mockery, by the soldiers in the Saviour’s right hand.The Wood of the Cross.

According to the legend connected with the Tree of Adam, the wood of the Cross on which our Lord was crucified was Cedar—a beam hewn from a tree which incorporated in itself the essence of the Cedar, the Cypress, and the Olive (the vegetable emblems of the Holy Trinity). Curzon, in his ‘Monasteries of the Levant,’ gives a tradition that the Cedar was cut down by Solomon, and buried on the spot afterwards called the Pool of Bethesda; that about the time of the Passion of our Blessed Lord the wood floated, and was used by the Jews for the upright posts of the Cross. Another legend makes the Cross of four kinds of wood representing the four quarters of the globe, or all mankind: it is not, however, agreed what those four kinds of wood were, or their respective places in the Cross. Some say they were the Palm, the Cedar, the Olive, and the Cypress; hence the line—“Ligna crucis Palma, Cedrus, Cupressus, Oliva.”

In place of the Palm or the Olive, some claim the mournful honour for the Pine and the Box; whilst there are others who aver it was made entirely of Oak. Another account states the wood to have been the Aspen, and since that fatal day its leaves have never ceased trembling with horror.

In some parts of England it is believed that the Elder was the unfortunate tree; and woodmen will look carefully into the faggots before using them for fuel, in case any of this wood should be bound up in them. The gipsies entertain the notion that the Cross was made of Ash; the Welsh that the Mountain Ash furnished the wood. In the West of England there is a curious tradition that the Cross was made of Mistletoe, which, until the time of our Saviour’s death, had been a goodly forest tree, but was condemned henceforth to become a mere parasite.

Sir John Maundevile asserts that the Cross was made of Palm, Cedar, Cypress, and Olive, and he gives the following curious account of its manufacture:—“For that pece that wente upright fro the erthe to the heved was of Cypresse; and the pece that wente overthwart to the wiche his honds weren nayled was of Palme; and the stock that stode within the erthe, in the whiche was made the morteys, was of Cedre; and the table aboven his heved, that was a fote and an half long, on the whiche the title was written, in Ebreu, Grece, and Latyn, that was of Olyve. And the Jewes maden the Cros of theise 4 manere of trees: for thei trowed that oure Lord Jesu Crist scholde han honged on the Cros als longe as the Cros myghten laste. And therfore made thei the foot of the Cros of Cedre: for Cedre may not in erthe ne in watre rote. And therfore thei wolde that it scholde have lasted longe. For thei trowed that the body of Crist scholde have stonken; therfore thei made that pece that went from the erthe upward, of Cypres: for it is welle smellynge, so that the smelle of His body scholde not greve men that wenten forby. And the overthwart pece was of Palme: for in the Olde Testament it was ordyned that whan on overcomen, He scholde be crowned with Palme. And the table of the tytle thei maden of Olyve; for Olyve betokenethe pes. And the storye of Noe wytnessethe whan that the culver broughte the braunche of Olyve, that betokend pes made betwene God and man. And so trowed the Jewes for to have pes whan Crist was ded: for thei seyd that He made discord and strif amonges hem.”Plants of the Crucifixion.

In Brittany the Vervain is known as the Herb of the Cross. John White, writing in 1624, says of it—In the Flax-fields of Flanders, there grows a plant called the Roodselken, the red spots on the leaves of which betoken the blood which fell on it from the Cross, and which neither rain nor snow has since been able to wash off. In Cheshire a similar legend is attached to the Orchis maculata, which is there called Gethsemane.

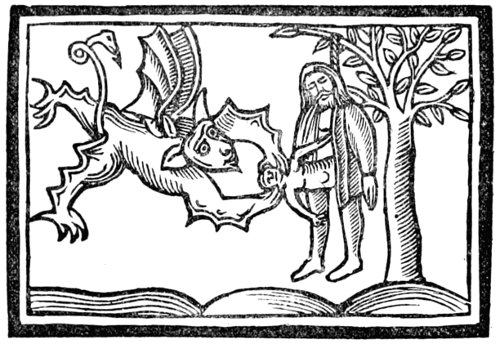

The Tree of Judas Iscariot.

In connection with the Crucifixion of our Lord many trees have had the ill-luck of bearing the name of the traitor Judas—the disciple who, after he had sold his Master, in sheer remorse and despair went and hanged himself on a tree.

The Tree of Judas. From Maundevile’s Travels.

Sir John Maundevile, from whose work the foregoing illustration has been copied, corroborates this view; for he tells us that in his day there stood in the vicinity of Mount Sion “the tree of Eldre, that Judas henge him self upon, for despeyr.”

A Russian proverb runs:—“There is an accursed tree which trembles without even a breath of wind,” in allusion to the Aspen (Populus tremula); and in the Ukraine they say that the leaves of this tree have quivered and shaken since the day that Judas hung himself on it.The Plants of St. John.

Popular tradition associates St. John the Baptist with numerous marvels of the plant world. St. John was supposed to have been born at midnight; and on the eve of his anniversary, precisely at twelve o’clock, the Fern blooms and seeds, and this wondrous seed, gathered at that moment, renders the possessor invisible: thus, in Shakspeare’s Henry IV., Gadshill says: “We have the receipt of Fern-seed, we walk invisible.” The Fairies, commanded by their queen, and the demons, commanded by Satan, engage in fierce combats at this mysterious time, for the possession of the invisible seed. In Russia, on St. John’s Eve, they seek the flower of the Paporot (Aspidium Filix mas), which flowers only at the precise moment of midnight, and will enable the lucky gatherer, who has watched it flower, to realise all his desires, to discover hidden treasures, and to recover cattle stolen or strayed. In the Ukraine it is thought that the gatherer of the Fern-flower will be endowed with supreme wisdom. The Russian peasants also gather, on the night of the Vigil of St. John, the Tirlic, or Gentiana Amarella, a plant much sought after by witches, and only to be gathered by those who have been fortunate enough first to have found the Plakun (Lythrum Salicaria), which must be gathered on the morning of St. John, without using a knife or other instrument in uprooting it. This herb the Russians hold to be very potent against witches, bad spirits, and the evil eye. A cross cut from the root of the Plakun, and worn on the person, causes the wearer to be feared as much as fire. Another herb which should be gathered on St. John’s Eve is the Hieracium Pilosella, called in Germany Johannisblut (blood of St. John): it brings good-luck, but must be uprooted with a gold coin. In many countries, before the break of day on St. John’s morning, the dew which has fallen on vegetation is gathered with great care. This dew is justly renowned, for it purifies all the noxious plants and imparts to certain others a fabulous power. By some it is treasured because it is believed to preserve the eyes from all harm during the succeeding year. In Venetia the dew is reputed to renew the roots of the hair on the baldest of heads. It is collected in a small phial, and a herb called Basilica is placed in it. In Normandy and the Pyrenees it is used as a wash to purify the skin; in Brittany it is thought that, thus used, it will drive away fever; and in Italy, Roumania, Sweden, and Iceland it is believed to soften and beautify the complexion. In Egypt the nucta or miraculous drop falls before sunrise on St. John’s Day, and is supposed to have the effect of stopping the plague. In Sicily they gather the Hypericum perforatum, or Herb of St. John, and put it in oil, which is by this means transformed into a balm infallible for the cure of wounds. In Spain garlands of flowers are plucked in the early morn of St. John’s Day, before the dew has been dried by the sun, and a favourite wether is decked with them, the village lasses singing—The populace of Madrid were long accustomed, on St. John’s Eve, to wander about the fields in search of Vervain, from a superstitious notion that this plant possesses preternatural powers when gathered at twelve o’clock on St. John’s Eve.

[The Birth of St. John the Baptist falls around the summer solstice, and is known as the “summer Christmas.” Picnics and bonfires on the eve of the feast are traditional, as Florence Berger explains. She also introduces some other customs from around the world for this feast day, including the hymn “Ut queant laxis.”DIRECTIONS

[June 24 is one of the oldest of the Church feasts. It is the birthday celebration of St. John the Baptist, and is sometimes called “summer Christmas.” On the eve of the feast, great bonfires were once lighted as a symbol of “the burning and brilliant” light, St. John, who pointed out Christ in this world of darkness. The solstice fires had been pagan, but now they were blessed by the Church in John’s honor. There are actual blessings for the bonfire in the Roman liturgy. Magical and superstitious elements of food and drink were forgotten, and we were encouraged to have great picnic feasts out-of-doors around the blazing logs. The outdoor grill, so popular in our own back yards, was once less selfish and more communal. We feasted as many neighbors and not as exclusive individuals. [There are all sorts of special foods used on the feast day of St. John. Each country makes a contribution to the joy and festivity. There is no world-fellowship quite so genuine as the mystical body of Christ celebrating. The St. John’s menu really is quite international. Wynkyn de Worde of old England cooked a wonderful soup for the occasion in the manner of his ancestors. In Mexico this is a day for bathing, singing, dancing and eating. Great hampers of chicken tamales and stuffed peppers are carried to the swimming parties. In Sweden salmon and new potatoes were the appropriate entree and strawberries were the dessert which was first choice. It was Latvia, however, which made a national holiday of this feast, and each man or boy with St. John’s name was honored. Every house had open house, and the table was set with cold cuts served with grated wild horseradish, bread, butter, honey and sweet beer. [Sweet beer was a sort of home brew which always was drunk on the great Latvian festivals. Barley and rye were moistened and germinated. The germination was then checked by complete drying; the resulting malted grain was roasted in an oven while hot water and hops were added. The brew was placed in barrels and strained through layers of straw. You can see how much trouble people will go to in order to celebrate. Naturally we prefer to substitute American beer for Latvian home brew. [Singing groups in the northern countries would go from door to door much like Christmas carolers only on this day they sang:“Ut queant laxis resonare fibris (Do-re) Mira gestorum famuli tuorum (Mi-fa) Solve poluti labei reatum (Sol-la) Sancte Johannes.” (Si)[“As thy servants sing with full voice the marvels of thy works, do thou purify their sinful lips Saint John.” And as the hymn mounted the scale from Do to Si, the housewife of Latvia would rush to the door with her hands full of bread and cheese while her husband stood in the background holding a mug of beer with which to lure in the singers. There was also a special cheese called John Siers or Saint John cheese. I believe it was made of goats’ milk like the brown cheese of Norway.[ [This idea of using bread and cheese as an attraction to entice guests into your house was employed as late at 1826 in Yorkshire, England. There, on St. John’s eve, the newcomers in a parish placed small tables holding bread and cheese and beer outside their doors. (They probably served the famous Wensleydale cheese, best of all English cheese. Wensleydale cheese is a double cream cheese, like Stilton, which grows “blue” when ripe. It is made only from June to September.) Passersby were thus invited to eat at the stranger’s door, and at the proper moment that door would open with a “come in” invitation. In this way, no new resident was a stranger for very long. There is much to be said for the custom because we have known how it is to live in a parish of strange names and faces. With all the moving days which we have here in America, we could use the bread and cheese lure for friendship several times a year in some families. [Last year in our home we celebrated St. John’s Day in games and plays and dances in front of the bonfire. It was fun to tell stories of ghosts and witches — all of whom would keep respectful distances from St. John’s light. Mary and Ann gathered St. John’s herbs from field and garden, and I told how they had been used as medicines, charms or food. Most of the yellow flowers once belonging to the cult of Balder, the sun god, are now St. John’s flowers. It is amazing to learn how many flowers are dedicated to this beloved saint. [When the flames had died down to glowing embers, we brought out the long-handled griddle and made sweet pancakes. You seldom think of pancakes at a grill, but they are excellent. The batter is easy to carry to a picnic in a Mason jar. The recipe we used was one from Finland where pancakes are the proper traditional supper on St. John’s eve. [Served with ripe red raspberries, fresh from the garden, Finnish Pancakes are sure to make your bonfire party a success.” Activity Source: Cooking for Christ by Florence Berger, National Catholic Rural Life Conference, 4625 Beaver Avenue, Des Moines, IA 50310, 1949, 1999 Catholic Culture] “In some parts of Russia the country people heat their baths on the Eve of St. John and place in them the herb Kunalnitza (Ranunculus); in other parts they place herbs, gathered on the same anniversary, upon the roofs of houses and stables, as a safeguard against evil spirits. The French peasantry rub the udders of their cows with similar herbs, to ensure plenty of milk, and place them over the doorways of cattle sheds and stables. “On the Eve of St. John, Lilies, Orpine, Fennel, and every variety of Hypericum are hung over doors and windows. Garlands of Vervain and Flax are also suspended inside houses; but the true St. John’s garland is composed of seven elements, namely white Lilies, green Birch, Fennel, Hypericum, Wormwood, and the legs of game birds: these are believed to have immense power against evil spirits. After daybreak on St. John’s Day it is dangerous to pluck herbs; the gatherer running the risk of being afflicted with cancer. “According to Bauhin, the following plants are consecrated to St. John:—First and specially the Hypericum, or perforated St. John’s Wort, the fuga dæmonum, or devil’s flight, so named from the virtue ascribed to it of frightening away evil spirits, and acting as a charm against witchcraft, enchantment, storms, and thunder. It is also called Tutsan, or All-heal, from its virtues in curing all kinds of wounds; and Sanguis hominis, because of the blood-red juice of its flowers. “The leaves of the common St. John’s Wort are marked with blood-like spots, which alway appear on the 29th of August, the day on which the Baptist was beheaded. The “Flower of St. John” is the Chrysanthemum (Corn Marigold), or, according to others, the Buphthalmus (Ox-Eye) or the Anacyclus. Grapes of St. John are Currants. The Belt or Girdle of St. John is Wormwood. The Herbs of St. John comprise also Mentha sarracenica or Costus hortensis; Gallithricum sativum or Centrum galli or Orminum sylvestre; in Picardy Abrotanum (a species of Southernwood); and, according to others, the Androsæmon (Tutsan), the Scrophularia, and the Crassula major. The scarlet Lychnis Coronaria is said to be lighted up on his day, and was formerly called Candelabrum ingens. A species of nut is named after the Saint. The Carob is St. John’s Mead, so called because it is supposed to have supplied him with food in the wilderness, and to be the “locusts” mentioned in the Scriptures.

Festival of St. John

“The festival of St. John would seem to be a favourite time with maidens to practice divination in their love affairs. On the eve of St. John, English girls set up two plants of Orpine on a trencher, one for themselves and the other for their lover; and they estimate the lover’s fidelity by his plant living and turning to theirs, or otherwise. They also gather a Moss-rose so soon as the dew begins to fall, and, taking it indoors, carefully keep it till New Year’s Eve, when, if the blossom is faded, it is a sign of the lover’s insincerity, but if it still retains its common colour, he is true. On this night, also, Hemp-seed is sown with certain mystic ceremonies. In Brittany, on the Saint’s Vigil, young men wearing bunches of green Wheat-ears, and lasses decked with Flax-blossoms, assemble round one of the old pillar-stones and dance round it, placing their wreath upon it. If it remains fresh for some time after, the lover is to be trusted, but should it wither within a day or two, so will the love prove but transient. In Sweden, on St. John’s Eve, young maidens arrange a bouquet composed of nine different flowers, among which the Hypericum, or St. John’s Wort, or the Ox-eye Daisy, St. John’s Flower, must be conspicuous. The flowers must be gathered from nine different places, and the posy be placed beneath the maiden’s pillow. Then he who she sees in her dreams will be sure soon to arrive.[7]Flowers of the Saints.

In the dark ages the Catholic monks, who cultivated with assiduity all sorts of herbs and flowers in their monastic gardens, came in time to associate them with traditions of the Church, and to look upon them as emblems of particular saints. Aware, also, of the innate love of humanity for flowers, they selected the most popular as symbols of the Church festivals, and in time every flower became connected with some saint of the Calendar, either from blowing about the time of the saint’s day, or from being connected with him in some old legend. St. Benedict’s herbs are the Avens, the Hemlock, and the Valerian, which were assigned to him as being antidotes; a legend of the saint relating that upon his blessing a cup of poisoned wine, which a monk had presented to him to destroy him, the glass was shivered to pieces. To St. Gerard was dedicated the Ægopodium Podagraria, because it was customary to invoke the saint against the gout, for which this plant was esteemed a remedy. St. Christopher has given his name to the Baneberry (Actæa spicata), the Osmund Fern (Osmunda regalis), the Fleabane (Pulicaria dysenterica), and, according to old herbalists, to several other plants, including Betonica officinalis, Vicia Cracca and Sepium, Gnaphalium germanicum, Spiræa ulmaria, two species of Wolf’s Bane, &c. St. George has numerous plants named after or dedicated to him. In England his flower is the Harebell, but abroad the Peony is generally called after him. His name is also bestowed on the Lilium convallium. The Herb of St. George is the Valeriana sativa; his root, Dentaria major; his Violet, Leucoium luteum; his fruit, Cucumis agrestis. In Asia Minor the tree of St. George is the Carob. The Eryngium was dedicated to St. Francis under the name of St. Francis’s Thorn. Bunium flexuosum, is St. Anthony’s nut—a pig-nut, because he is the patron of pigs; and Senecio Jacobæa is St. James’s Wort (the saint of horses and colts)—used in veterinary practice. The Cowslip is dedicated to St. Peter, as Herb Peter of the old herbals, from some resemblance which it has to his emblem—a bunch of keys. As the patron of fishermen, Crithmum maritimum, which grows on sea-cliffs, was dedicated to this saint, and called in Italian San Pietro, in French Saint Pierre, and in English Samphire. Most of these saintly names were, however, given to the plants because their day of flowering is connected with the festival of the saint. Hence Hypericum guadrangulare is the St. Peter’s Wort of the modern floras, from its flowering on the 29th of June. The Daisy, as Herb Margaret, is popularly supposed to be dedicated to “Margaret that was so meek and mild;” probably from its blossoming about her day, the 22nd of February: in reality, however, the flower derived its name from St. Margaret of Cortona. Barbarea vulgaris, growing in the winter, is St. Barbara’s Cress, her day being the fourth of December, old style; and Centaurea solstitialis derives its Latin specific, and its popular name, St. Barnaby’s Thistle, from its flourishing on the longest day, the 11th of June, old style, which is now the 22nd. Nigella damascena, whose persistent styles spread out like the spokes of a wheel, is named Katharine’s flower, after St. Katharine, who suffered martyrdom on a wheel. The Cranesbill is called Herb Robert, in honour of St. Robert, Abbot of Molesme and founder of the Cistercian Order. The Speedwell is St. Paul’s Betony. Archangel is a name given to one umbelliferous and three labiate plants. An angel is said to have revealed the virtues of the plants in a dream. The umbelliferous plant, it has been supposed, has been named Angelica Archangelica, from its being in blossom on the 8th of May, old style, the Archangel St. Michael’s Day. Flowering on the fête day of such a powerful angel, the plant was supposed to be particularly useful as a preservative of men and women from evil spirits and witches, and of cattle from elfshot. Roses are the special flowers of martyrs, and, according to a tradition, they sprang from the ashes of a saintly maiden of Bethlehem who perished at the stake. Avens (Geum urbanum) the Herba benedicta, or Blessed Herb, is a plant so blessed that no venomous beast will approach within scent of it; and, according to the author of the Ortus sanitatis, “where the root is in a house, the devil can do nothing, and flies from it, wherefore it is blessed above all other herbs.” The common Snowdrops are called Fair Maids of February. This name also, like the Saints’ names, arises from an ecclesiastical coincidence: their white flowers blossom about the second of February, when maidens, dressed in white, walked in procession at the Feast of the Purification. The name of Canterbury Bells was given to the Campanula, in honour of St. Thomas of England, and in allusion probably to the horse-bells of the pilgrims to his shrine. Saxifraga umbrosa is both St. Patrick’s cabbage and St. Anne’s needlework; Polygonum Persicaria is the Virgin’s Pinch; Polytrichum commune, St. Winifred’s Hair; Myrrhis odorata, Sweet Cicely; Origanum vulgare, Sweet Margery; Oscinium Basilicum, Sweet Basil. Angelica sylvestris, the Root of the Holy Ghost; Hedge Hyssop, Cranesbill, and St. John’s Wort are all surnamed Grace of God; the Pansy, having three colours on one flower, is called Herb Trinity; the four-leaved Clover is an emblem of the Cross, and all cruciform flowers are deemed of good omen, having been marked with the sign of the Cross. The Hemp Agrimony is the Holy Rope, after the rope with which Christ was bound; and the Hollyhock is the Holy Hock (an old word for Mallow). The feeling which inspired this identification of flowers and herbs with holy personages and festivals is gracefully expressed by a Franciscan in the following passage:—“Mindful of the Festivals which our Church prescribes, I have sought to make these objects of floral nature the timepieces of my religious calendar, and the mementos of the hastening period of my mortality. Thus I can light the taper to our Virgin Mother on the blowing of the white Snowdrop, which opens its flower at the time of Candlemas; the Lady’s Smock and the Daffodil remind me of the Annunciation; the blue Harebell, of the Festival of St. George; the Ranunculus, of the Invention of the Cross; the Scarlet Lychnis, of St. John the Baptist’s day; the white Lily, of the Visitation of our Lady; and the Virgin’s Bower, of the Assumption; and Michaelmas, Martinmas, Holy Rood, and Christmas have all their appropriate decorations.” In later times we find the Church’s Calendar of English flowers embodied in the following lines:—| DATE. | SAINT. | APPROPRIATE FLOWER. |

|---|---|---|

| Nov. 30. | S. Andrew. | S. Andrew’s Cross—Ascyrum Crux Andreæ. |

| Dec. 21. | S. Thomas. | Sparrow Wort—Erica passerina. |

| Dec. 25. | Christmas. | Holly—Ilex bacciflora. |

| Dec. 26. | S. Stephen. | Purple Heath—Erica purpurea. |

| Dec. 27. | S. John Evan. | Flame Heath—Erica flammea. |

| Dec. 28. | Innocents. | Bloody Heath—Erica cruenta. |

| Jan. 1. | Circumcision. | Laurustine—Viburnum tinus. |

| Jan. 6. | Epiphany. | Screw Moss—Tortula rigida. |

| Jan. 25. | Conversion of S. Paul. | Winter Hellebore—Helleborus hyemalis. |

| Feb. 2. | Purification of B. V. M. | Snowdrop—Galanthus nivalis. |

| Feb. 24. | S. Matthias. | Great Fern—Osmunda regalis. |

| Mar. 25. | Annunciation of B. V. M. | Marigold—Calendula officinalis. |

| Apr. 25. | S. Mark. | Clarimond Tulip—Tulipa præcox. |

| May 1. | S. Philip and S. James. | Tulip—Tulipa Gesneri, dedicated to S. Philip. Red Campion—Lychnis dioica rubra. Red Bachelor’s Buttons—Lychnis dioica plena, dedicated to S. James. |

| June 11. | S. Barnabas. | Midsummer Daisy—Chrysanthemum leucanthemum. |

| June 24. | S. John Baptist. | S. John’s Wort—Hypericum pulchrum. |

| June 29. | S. Peter | Yellow Rattle—Rhinanthus Galli. |

| July 25. | S. James | Herb Christopher—Actæa spicata. |

| Aug. 24. | S. Bartholomew | Sunflower—Helianthus annuus. |

| Sept. 21. | S. Matthew | Ciliated Passion-flower.—Passiflora ciliata. |

| Sept. 29. | S. Michael. | Michaelmas Daisy—Aster Tradescanti. |

| Oct. 18. | S. Luke. | Floccose Agaric—Agaricus floccosus. |

| Oct. 28. | S. Simon and S. Jude | Late Chrysanthemum—Chrysanthemum serotinum. Scattered Starwort—Aster passiflorus, dedicated to S. Jude. |

| Nov. 1. | All Saints. | Amaranth. |

Flowers of the Church’s Festivals.

In the services of the Church every season has its appropriate floral symbol. In olden times on Feast days places of worship were significantly strewed with bitter herbs. On the Feast of Dedication (the first Sunday in October) the Church was decked with boughs and strewn with sweet Rushes; for this purpose Juncus aromaticus (now known as Acorus Calamus) was used.It being also the festival of SS. Philip and James, the feast partook somewhat of a religious character. The people not only turned the streets into leafy avenues, and their door-ways into green arbours, and set up a May-pole decked with ribands and garlands, and an arbour besides for Maid Marian to sit in, to witness the sports, but the floral decorations extended likewise into the Church. We learn from Aubrey that the young maids of every parish carried about garlands of flowers, which they afterwards hung up in their Churches; and Spenser sings how, at sunrise—

The beautiful milk-white Hawthorn blossom is essentially the flower of the season, but in some parts of England the Lily of the Valley is considered as “The Lily of the May.” In Cornwall and Devon Lilac is esteemed the May-flower, and special virtues are attached to sprays of Ivy plucked at day-break with the dew on them. In Germany the Kingcup, Lily of the Valley, and Hepatica are severally called Mai-blume.

Whitsuntide flowers in England are Lilies of the Valley and Guelder Roses, but according to Chaucer (‘Romaunt of the Rose’) Love bids his pupil—The Germans call Broom Pentecost-bloom, and the Peony the Pentecost Rose. The Italians call Whitsunday Pasqua Rosata, Roses being then in flower.

To Trinity Sunday belong the Herb-Trinity or Pansy and the Trefoil. On St. Barnabas Day, as on St. Paul’s Day, the churches were decked with Box, Woodruff, Lavender, and Roses, and the officiating Priests wore garlands of Roses on their heads. On Royal Oak Day (May 29th), in celebration of the restoration of King Charles II., and to commemorate his concealment in an aged Oak at Boscobel, gilded Oak-leaves and Apples are worn, and Oak-branches are hung over doorways and windows. From this incident in the life of Charles II., the Oak derives its title of Royal.Gospel Oaks and Memorial Trees.

There exist in different parts of England several ancient trees, notably Oaks, which are traditionally said to have been called Gospel trees in consequence of its having been the practice in times long past to read under a tree which grew upon a boundary-line a portion of the Gospel on the annual perambulation of the bounds of the parish on Ascension Day. In Herrick’s poem of the ‘Hesperides’ occur these lines in allusion to this practice:—Many of these old trees were doubtless Druidical, and under their “leafy tabernacles” the pioneers of Christianity had probably preached and expounded the Scriptures to a pagan race. The heathen practice of worshipping the gods in woods and trees continued for many centuries, till the introduction of Christianity; and the first missionaries sought to adopt every means to elevate the Christian worship to higher authority than that of paganism by acting on the senses of the heathen. St. Augustine, Evelyn tells us, held a kind of council under an Oak in the West of England, concerning the right celebration of Easter and the state of the Anglican church; “where also it is reported he did a great miracle.” On Lord Bolton’s estate in the New Forest stands a noble group of twelve Oaks known as the Twelve Apostles: there is another group of Oaks extant known as the Four Evangelists. Beneath the venerable Yews at Fountain Abbey, Yorkshire, the founders of the Abbey held their council in 1132.

“Cross Oaks” were so called from their having been planted at the junction of cross roads, and these trees were formerly resorted to by aguish patients, for the purpose of transferring to them their malady. Venerable and noble trees have in all ages and in all countries been ever regarded with special reverence. From the very earliest times such trees have been consecrated to holy uses. Thus, the Gomerites, or descendants of Noah, were, if tradition be true, accustomed to offer prayers and oblations beneath trees; and, following the example of his ancestors, the Patriarch Abraham pitched his tents beneath the Terebinth Oaks of Mamre, erected an altar to the Lord, and performed there sacred and priestly rites. Beneath an Oak, too, the Patriarch entertained the Deity Himself. This tree of Abraham remained till the reign of Constantine the Great, who founded a venerable chapel under it, and there Christians, Jews, and Arabs held solemn anniversary meetings, believing that from the days of Noah the spot shaded by the tree had been a consecrated place. Dean Stanley tells us that “on the heights of Ephraim, on the central thoroughfare of Palestine, near the Sanctuary of Bethel, stood two famous trees, both in after times called by the same name. One was the Oak-tree or Terebinth of Deborah, under which was buried, with many tears, the nurse of Jacob (Gen. xxxv. 8). The other was a solitary Palm, known in after times as the Palm-tree of Deborah. Under this Palm, as Saul afterwards under the Pomegranate-tree of Migron, as St. Louis under the Oak-tree of Vincennes, dwelt that mother in Israel, Deborah, the wife of Lapidoth, to whom the sons of Israel came to receive her wise answers.” Since the time when Solomon cut the Cedars of Lebanon for the purpose of employing them in the erection of the Temple of the Lord, this renowned forest has been greatly shorn of its glories; but a grove of nearly four hundred trees still exists. Twelve of the most valuable of these trees bear the titles of “The Friends of Solomon,” or “The Twelve Apostles.” Every year the Maronites, Greeks, and Armenians go up to the Cedars, at the Feast of the Transfiguration, and celebrate mass on a homely stone altar erected at their feet. In Evelyn’s time there existed, near the tomb of Cyrus, an extraordinary Cypress, which was said to exude drops of blood every Friday. This tree, according to Pietro della Valla, was adorned with many lamps, and fitted for an oratory, and was for ages resorted to by pious pilgrims. Thevenot and other Eastern travellers mention a tree which for centuries had been regarded with peculiar reverence. “At Matharee,” says Thevenot, “is a large garden surrounded by walls, in which are various trees, and among others, a large Sycamore, or Pharaoh’s Fig, very old, which bears fruit every year. They say that the Virgin passing that way with her son Jesus, and being pursued by a number of people, the Fig-tree opened to receive her; she entered, and it closed her in, until the people had passed by, when it re-opened, and that it remained open ever after to the year 1656, when the part of the trunk that had separated itself was broken away.” Near Kennety Church, in the King’s County, Ireland, is an Ash, the trunk of which is nearly 22 feet round, and 17 feet high, before the branches break out, which are of enormous bulk. When a funeral of the lower class passes by, they lay the body down a few minutes, say a prayer, and then throw a stone to increase the heap which has been accumulating round the roots. The Breton nobles were long accustomed to offer up a prayer beneath the branches of a venerable Yew which grew in the cloister of Vreton, in Brittany. The tree was regarded with much veneration, as it was said to have originally sprung from the staff of St. Martin. In England, the Glastonbury Thorn was long the object of pious reverence. This tree was supposed to have sprung from the staff of Joseph of Arimathea, to whom the original conversion of this country is attributed in monkish legends. The story runs that when Joseph of Arimathea came to convert the heathen nations he selected Glastonbury as the site for the first Christian Church, and whilst preaching there on Christmas-day, he struck his staff into the ground, which immediately burst into bud and bloom; eventually it grew into a Thorn-bush, which regularly blossomed every Christmas-day, and became known throughout Christendom as the Glastonbury Thorn.Like the Thorn of Glastonbury, an Oak, in the New Forest, called the Cadenham Oak, produced its buds always on Christmas Day; and was, consequently, regarded by the country people as a tree of peculiar sanctity. Another miraculous tree is referred to in Collinson’s ‘History of Somerset.’ The author, speaking of the Glastonbury Thorn, says that there grew also in the Abbey churchyard, on the north side of St. Joseph’s Chapel, a miraculous Walnut-tree, which never budded forth before the Feast of St. Barnabas (that is, the 11th of June), and on that very day shot forth leaves, and flourished like its usual species. It is strange to say how much this tree was sought after by the credulous; and though not an uncommon Walnut, Queen Anne, King James, and many of the nobility of the realm, even when the times of monkish superstition had ceased, gave large sums of money for small cuttings from the original. Folkard, Plant Lore, Legends and Lyrics

Discover more from Jacki Kellum

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.